Abstract

The bifunctional N5,N10-methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase (DHCH or FolD), which is widely distributed in prokaryotes and eukaryotes, is involved in the biosynthesis of folate cofactors that are essential for growth and cellular development. The enzyme activities represent a potential antimicrobial drug target. We have characterized the kinetic properties of FolD from the Gram-negative pathogen Acinetobacter baumanni and determined high-resolution crystal structures of complexes with a cofactor and two potent inhibitors. The data reveal new details with respect to the molecular basis of catalysis and potent inhibition. A unexpected finding was that our crystallographic data revealed a different structure for LY374571 (an inhibitor studied as an antifolate) than that previously published. The implications of this observation are discussed.

Keywords: antifolate, cyclohydrolase, dehydrogenase, enzyme inhibition, X-ray structure

Introduction

Multidrug resistant bacteria represent a major health threat and an increasingly difficult problem in the hospital environment [1]. Drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria such as Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, in particular, pose a significant therapeutic challenge with strains resistant to some or all common therapeutic agents [2-4]. New drugs are urgently sought to combat this problem, with different strategies being employed [5]. We have adopted a target-based approach [6] seeking to characterize, validate and assess specific enzymes for their potential to underpin early-stage drug antimicrobial discovery. Of particular interest is folate metabolism, which supplies the derivatives required to support essential biosynthetic pathways [7,8].

The enzymes of folate metabolism are key to the biosynthesis of thymidine, purines and amino acids (glycine and methionine), as well as the metabolism of histidine and serine [9,10]. Several enzymes modify tetrahydrofolate (THF) to supply methyl-, methylene, formyl- and unsubstituted THF derivatives. One important intermediate N10-formylTHF can be formed by in two steps: from N5,N10-methyleneTHF to N5, i>N10-methenylTHF [by the NADP+ or NAD+ dependent N5,N10-methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase (DH)], which is subsequently hydrolyzed to N10-formylTHF [by N5,N10-methenyltetrahydrofolate cyclohydrolase (CH)] (Fig. 1). These enzyme activities occur in different combinations. In bacteria, dehydrogenase and cyclohydrolase activities are provided by a bifunctional enzyme (annotated as FolD or DHCH). Many eukaryotes possess a longer poly-peptide, which includes an additional N10-formylTHF ligase domain. A number of crystal structures have been reported and these include the cytosolic DC (dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase) domain of the human trifunctional enzyme in complex with the cofactor and inhibitors [11,12], the enzyme from Escherichia coli [13] and Leishmania major [7]. In addition, the monofunctional NAD+ dependent yeast DH has been described [14]. We previously reported the structure and ligand discovery research targeting P. aeruginosa FolD (PaFolD) [8]. However, we were unable to determine crystal structures of ligand complexes either with potent inhibitors or the novel hits that we identified. We sought an alternative and switched to the A. baumannii enzyme (AbFolD) to provide structural data. In the present study, we describe the kinetic characterization and high-resolution crystal structures of AbFolD, in the presence of ligands, substrate and catalytic intermediate mimics. The structures reveal molecular details relevant to the enzyme mechanism and serve to raise questions about previous proposals involving a channelling process. They inform on potent inhibition and, moreover, revealed an unexpected finding that forced a re-evaluation of a previously characterized FolD inhibitor: the antifolate LY374571.

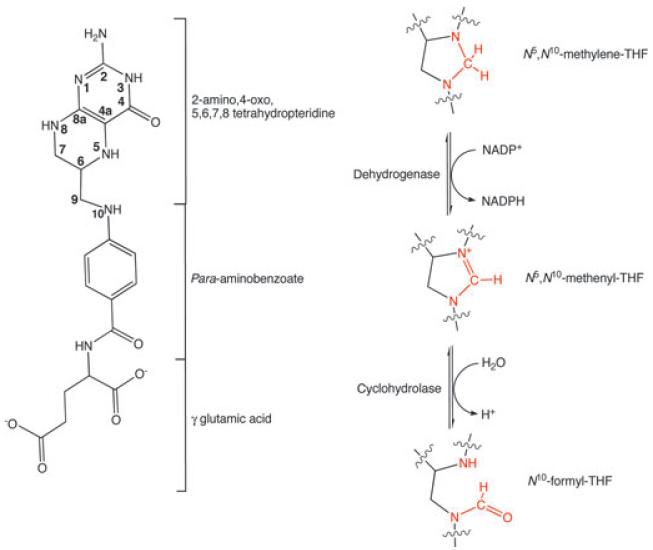

Fig. 1.

The enzymatic pathway of AbFolD showing (left) the chemical structure of tetrahydrofolate as a reference. (right) The two stages of the reaction catalysed by AbFolD, starting with the NADP+ reduction of N5,N10 methylene tetrahydrofolate to N5,N10 methenyl tetrahydrofolate, followed by the subsequent hydrolytic opening of the ring to form N10 formyl tetrahydrofolate.

Results and Discussion

Kinetic analysis

A highly efficient recombinant source of AbFolD was established to supply material for characterization. The AbFolD dehydrogenase activity was measured by monitoring the conversion of N5,N10-methylenetetrahydrofolate to N5,N10-methenyltetrahydrofolate. Measuring the decrease of N5,N10-methenyltetrahydrofolate provided the cyclohydrolase activity. The enzyme kinetic data are presented in Table 1. We purchased the substrate for the dehydrogenase assay, rather than producing it by condensation from tetrahydrofolate and formaldehyde. This aimed to avoid the additional reactivity of excess formaldehyde in the reaction mix. AbFolD gave specific activities of 161.4 ± 5.7 and 350.2 ± 4.4 μmol·miN−1·mg−1 for the dehydrogenase and cyclohydrolase respectively, which, although high compared to the human DHCH (19 and 133 μmol·miN−1·mg−1) and L. major DHCH (22 and 6.3 μmol·miN−1·mg−1), are comparable with values reported for bacterial enzymes. These include the E. coli and Peptrostreptococcus productus enzymes, which showed a dehydrogenase activity of 200 and 627 μmol·miN−1·mg−1 respectively and that of Clos-tridium formicoaceticum with a cyclohydrolase activity of 469 μmol·miN−1·mg−1 [15-19]. The Km values determined for NADP+, the N5,N10-methylenetetrahydrofolate substrate and N5,N10-methenyltetrahydrofolate intermediate, or second substrate, are 71.9 ± 6.0, 26.8 ± 2.2 and 40.3 ± 6.9 μm respectively. The substrate analogue LY354899 has previously been shown to be a competitive inhibitor of the DH activity of human DHCH (29 nm), PaFolD (30 nm) and L. major FolD (105 nm) [8,12,18]. However, little work has been carried out regarding cyclohydrolase activity, presumably with the assumption that inhibition against one activity will result in inhibition of the other. LY354899 and the compound designated as LY374571 gave Ki values with respect to the dehydrogenase activity of 116 ± 2.4 nm and 45.8 ± 4.1 nm, respectively. As will be explained, the structure of LY374571 is different from that of the compound characterized in the present study. Nevertheless, both compounds were significantly more potent inhibitors against the cyclohydrolase activity with Ki values of 7.1 ± 1.6 nm and 5.6 ± 1.7 nm respectively, suggesting that they represent good mimics of substrates, products or catalytic intermediates. These low Ki values molecules encouraged us to seek out structural data informing on the molecular basis of inhibition.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for AbFolD.

| K m | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (M−1.s−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First substrate | 26.8 ± 2.2 | 88.3 ± 2.0 | 3.2 × 106 |

| NADP+ | 71.9 ± 6.0 | 84.7 ± 2.0 | 1.1 × 106 |

| Second substrate | 40.3 ± 6.9 | 141.6 ± 11.3 | 3.5 × 106 |

Overall structure

The crystal structure of the binary AbFolD-NADP+ complex was solved to a resolution of 1.45 Å, whereas the ternary structures with the inhibitors were determined to a resolution of 2.0 Å (Table 2). In all three structures, the main chain atoms are well defined by the electron density, although there are several side chains in a flexible loop (residues 231–243) that were poorly ordered and assigned zero occupancy.

Table 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics.

| NADP+ complex | NADP+–inhibitor complex | NADP+–LY354899 complex | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spacegroup | P21 | P21 | P21 |

| Unit cellparameters, a, b, c, (Å) and β | 55.0, 80.1, 68.6, 107° | 55.5, 80.9, 68.5, 107° | 55.2, 80.5, 68.5, 107° |

| Resolution range (Å)a | 52.6–1.45 (1.53–1.45) | 20.86–2.00 (2.11–2.00) | 20.67–2.00 (2.11–2.00) |

| Number of measurements | 357 135 (47 440) | 91 096 (12 233) | 87 114 (11 109) |

| Number of unique reflections | 100 394 (14559) | 38 850 (5634) | 36 783 (4948) |

| Multiplicity | 3.6 (3.3) | 2.3 (2.2) | 2.4 (2.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.7 (99.3) | 99.0 (99.1) | 95.2 (88.4) |

| Mean I/σI | 13.1 (2.9) | 18.7 (8.1) | 12.9 (6.3) |

| Wilson B (Å2) | 14.9 | 18.9 | 15.9 |

| R merge b | 0.055 (0.423) | 0.030 (0.095) | 0.044(0.118) |

| Rworkc/Rfreed | 0.122/0.152 | 0.171/0.214 | 0.168/0.208 |

| rmsd bonds (Å) | 0.0085 | 0.0051 | 0.005 |

| rmsd angles (°) | 1.478 | 1.146 | 1.132 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |||

| Favoured/allowed | 99.0/1.0 | 98.1/1.9 | 98.2/1.8 |

| Protein residues/atoms | 568/4329 | 564/4175 | 564/4207 |

| Overall B (Å2) chain A/B | 16.9/16.4 | 22.1/19.1 | 16.7/15.2 |

| Waters | 740 | 592 | 654 |

| Overall B (Å2) | 30.5 | 24.8 | 21.2 |

| NADP+ | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Overall B (Å2) | 27.2/26.1 | 27.7/25.2 | 24.2/23.3 |

| Inhibitors | – | 2 | 2 |

| Overall B (Å2) | – | 18.0/15.8 | 12.9/12.1 |

| Poly(ethylene glycol)/glycerol/Cl− | 1/5/5 | –/2/1 | –/2/1 |

| Overall B (Å2) | 39.2/32.2/20.7 | 30.8/17.4 | 30.9/14.6 |

Values in parentheses refer to the highest resolution bin.

Rmerge = ΣhΣi||(h,i) − <I(h)> Σh ΣI |(h,i).

Rwork = Σhkl||Fo| − |Fc||/Σ|Fo|, where Fo is the observed structure factor and Fc is the calculated structure factor.

Rfree is the same as Rwork, except it is calculated using 5% of the data that are not included in any refinement.

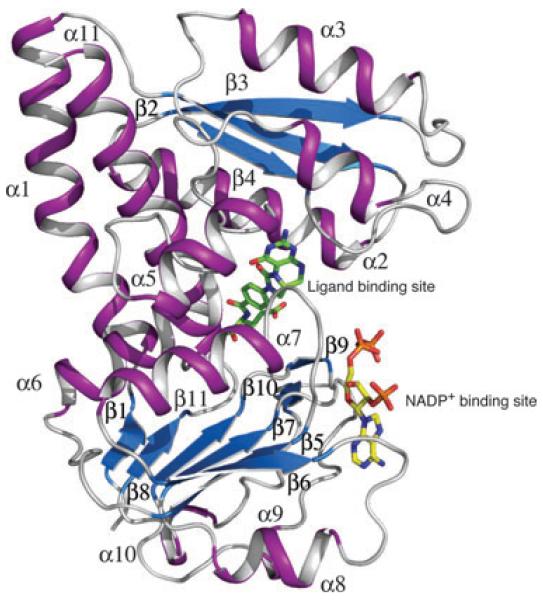

The AbFolD subunit, a polypeptide of 282 amino acids, displays the tertiary structure typical of DHCH enzymes (Fig. 2). This consists of 11 α-helices and 11 β-strands forming a two-domain structure with the N-terminal domain encompassing residues 6–150 and the C-terminal domain encompassing residues 150–262. The N-terminal domain contains the catalytic site where the inhibitors bind and is discussed separately. The C-terminal domain displays the Rossmann fold and here the NADP+ cofactor binds in an extended conformation in a deep cleft. The amino acids that form the cofactor binding site are highly conserved [7,8]. In common with several other structures, in the present study, the AbFolD cofactor complex shows well-defined electron density for the adenine and phosphate groups but not for the nicotinamide and associated ribose. The adenine binds in a hydrophobic pocket on the outer surface of the enzyme and, together with other components, participates in direct and solvent-mediated hydrogen-bond interactions to functional groups on the enzyme in a fashion similar to that described previously [7]. Structures of human DHCH [11] and Thermoplasma acidophilum FolD [17] show ordered NADP+ and superposition on the structure of AbFolD highlights the conserved nature of the cofactor binding sites and also suggests how the nicotinamide binds adjacent to the catalytic centre (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Ribbon diagram of an AbFolD subunit. An inhibitor (green sticks) and NADP+ (yellow sticks) occupy the catalytic and cofactor binding sites, respectively. α-helices and β-strands are labelled and coloured purple and blue, respectively.

AbFolD forms a dimer in solution, as revealed by size exclusion chromatography. This dimer, which is a common feature of FolD, constitutes the asymmetric unit of the crystal structures. The dimer interface is predominantly polar and primarily involves interactions formed between residues on α5, α7 and β6 of noncrystallographically related subunits (Fig. S1). Approximately 10% (2880 Å2) of a subunit surface is occluded from solvent by dimer formation. The active site is distant from the dimer interface, suggesting that the dimerization is not necessary for activity. Superposition of the crystallographically independent subunits in the three structures gives rmsd values in the range 0.22–0.27 Å over 282 main chain atoms, indicating that the binary and ternary complexes display a highly similar overall structure. This value is significantly less than that seen for other DHCH enzymes, which show a significant difference between the binding clefts in the molecules in the asymmetric unit; this difference can be attributed to distinct domain orientations [7].

The structural basis of inhibition

The folate-binding site, the catalytic centre, is located in a deep, water filled pocket on the N-terminal domain formed principally by contributions from α2, α4, β4 and α10, as well as the linking regions between α4–α5, β11–α11 and the β8–β9 hairpin (Fig. 2). Although there are no gross conformational changes between the binary and ternary complexes, a specific difference is the placement of the Tyr49 side chain. In the presence of inhibitors, the side chain swivels to stack onto the para-aminobenzoate moieties. In addition, His98 adopts a dual conformation in the binary complex with one position occluding the active site but, in the presence of the inhibitors, this rotamer is not observed.

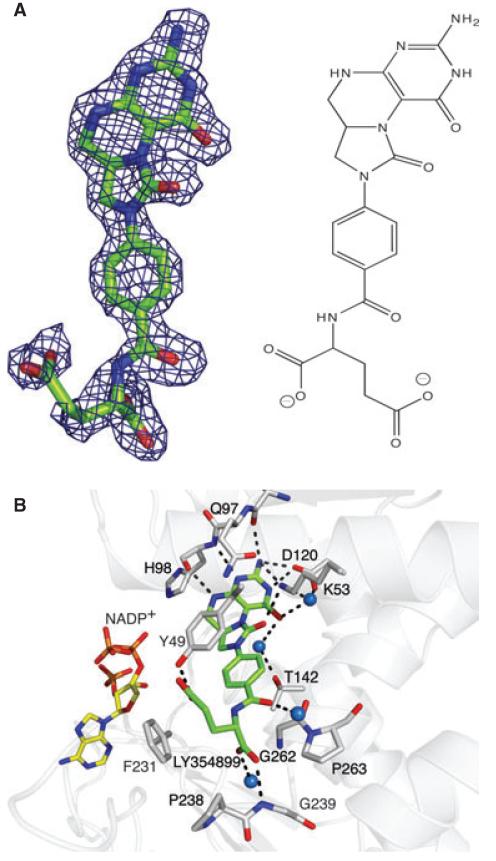

LY354899 binds in a bent conformation (Fig. 3A). The pteridine moiety is wedged between Gln97 and Ile169, forming direct hydrogen-bonding interactions to the side chain of Asp120, the main chain carbonyl of Leu96, the main chain carbonyl and amide of His98 and to the side chain of Lys53 (Fig. 3B). Solvent-mediated interactions also help link the pteridine O4 to the enzyme. As noted above, the side chain of Tyr49 forms π-stacking interactions on one side of the para-aminobenzoate segment; on the other side, Gly262 and side chains of Thr265 and Ile266 (not shown) contribute to van der Waals interactions with the inhibitor. The glutamate tail of the inhibitor forms two direct hydrogen bonds with the enzyme. These involve Tyr49 OH and the amide of Gly239. The former helps to position the aromatic side chain over the para-aminobenzoate segment. Several solvent-mediated interactions (one of which is depicted in Fig. 3B) link the acidic tail to the enzyme. The side chains of Met52 (not shown) and Phe231, together with Pro238, form a hydrophobic clamp to assist positioning and binding of the tail.

Fig. 3.

LY354899 bound to AbFolD. (A) The Fo − Fc omit map (blue chicken wire) contoured at 2σ and the chemical structure of LY354899. (B) Details of binding in the active site. Residues and waters (blue spheres) that interact are labelled. Dashed bonds represent potential hydrogen-bonding associations. The fragment of the cofactor that could be modelled is shown as sticks with atomic positions coloured yellow for C, blue for N, orange for P and red for O. The C atoms of LY354899 and the FolD residues are green and grey, respectively.

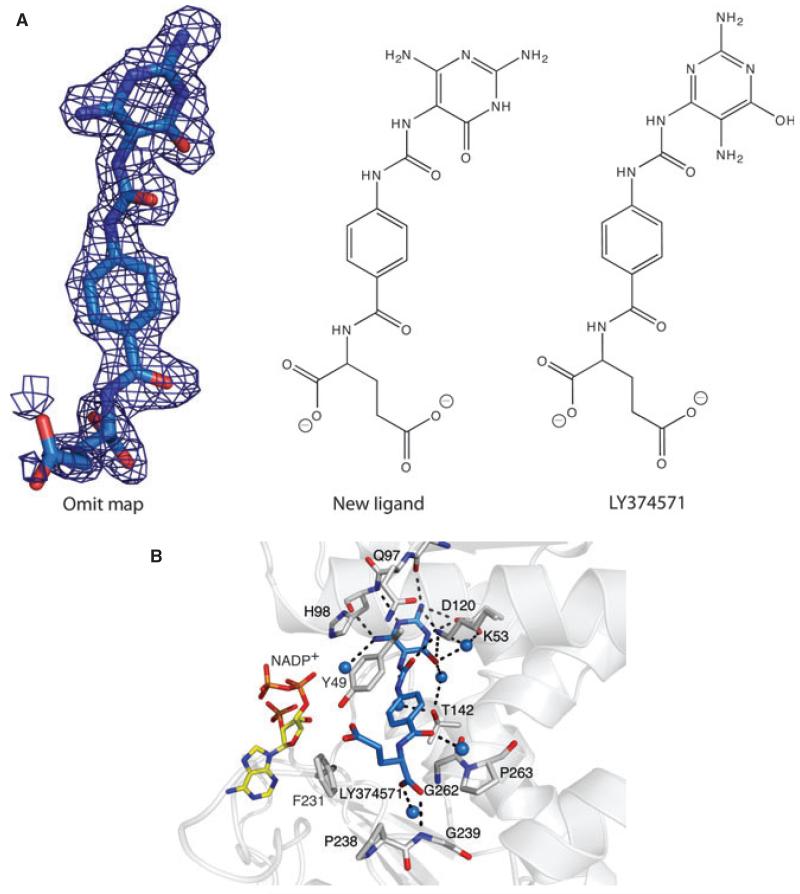

Analysis of what we considered would be the LY374571 complex revealed an unexpected finding. Well-defined electron density indicated the presence of an inhibitory ligand. However, although there were similarities in respect of the para-aminobenzoate tail, the head group was obviously distinct and incompatible with the chemical structure assigned to LY374571 (Fig. 4A). By consideration of the hydrogen-bonding pattern, the synthetic route that was followed and analytical data, we assigned the inhibitor as 2-(4-(3-(2,4-diamino-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidin-5-yl)ureido) benzamido)pentanedioic acid. This compound is assigned the code PDB 9L9 in the Protein Data Bank (PDB).

Fig. 4.

A new inhibitor bound to AbFolD. The inhibitor is 2-(4-(3-(2,4-diamino-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidin-5-yl)ureido)benzamido)pentanedioic acid and has been assigned the code 9L9 in the PDB. A similar colour scheme as in Fig. 3 is applied, except the C atoms of the inhibitor are coloured cyan. (A) Left: the Fo − Fc omit map contoured at the 2σ level. Centre: the chemical structure assigned of 9L9. Right: the chemical structure assigned to LY374571. (B) Residues and waters that interact with the new pyrimidine derivative.

The ligand binds to AbFolD in a similar fashion to LY354899 exploiting functional groups on the enzyme in hydrogen bond formation and van der Waals interactions (Fig. 4B). The conservation of interactions can be explained by the close spatial agreement and hydrogen-bonding capacity of functional groups on the inhibitors. The similarity in the mode of binding to AbFolD extends to the conservation of the water molecules that mediate links between the ligands and the enzyme. A chemical difference between the two inhibitors occurs at the link between heterocyclic moietes and the para-aminobenzoate segment. The ureido link provides two amide groups and they combine to form hydrogen bonds to a water molecule and this in turn participates in a solvent network in the active site. A minor difference involves the lack of a hydrogen bond between the glutamate tail and Tyr49 OH in the case of the ureido compound. Here, the tail adopts a slightly different orientation, with one carboxylate group directed out of the active site.

We had followed the reported synthetic route to LY374571 and our analytical data were in excellent agreement with that reported previously [12]. This is to be expected given that the compounds are structural isomers. The highly-defined electron density in the AbFolD crystal structure, together with the sensible chemical interactions, in particular the hydrogen-bonding assignments, provides confidence in our structure. The synthetic method may have produced a different compound in our hands or the original assignment of the LY374571 structure was in error. We sought to understand the discrepancy and so considered the evidence for the LY374571 structure and also the factors involved in the synthetic reaction.

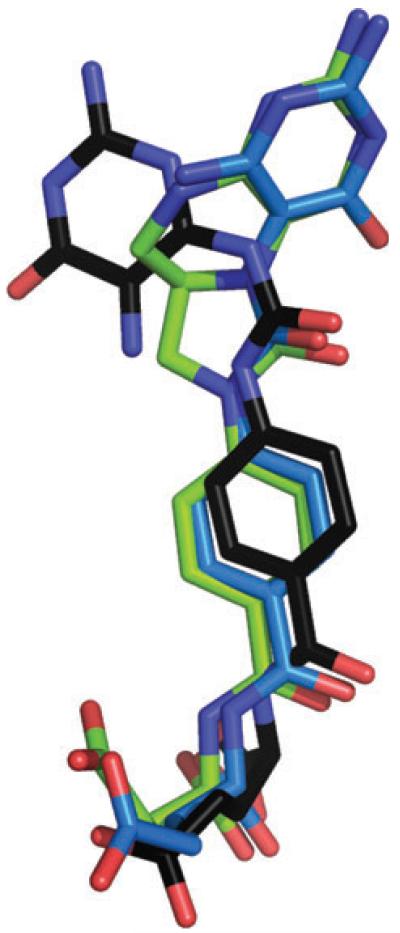

The study describing the complex of human DHCH with LY374571 [12] did not provided an illustration of the electron density for the ligand; therefore, we calculated an omit difference density map using the deposited structure factors (Fig. S2). The map shows a density that might represent water molecules but certainly not a bound, well-ordered inhibitor. The occupancy of the LY374571 atoms had been set at 0.25 in the complex to obtain B-factors comparable to that observed for active site residues. This approach might not be considered best practice, potentially leading to phase bias and misinterpretation. The structures described in the present study show an unambiguous density for both ligands, which have been refined with full occupancy and display B-factors that are significantly less than the overall B-factor of the protein atoms (Table 2). The DHCH-LY374571 structure is also deficient in terms of chemical sense. The pyrimidine ring is positioned differently compared to our structure (Fig. 5) and the six associated functional groups make only a single hydrogen bond to the protein and few van der Waals contacts. For a compound that displays such a low Ki, this might be considered unusual. In addition, the conformation of LY374571 places two hydrogen bond donor groups, NH and NH2, approximately 2.2 Å apart; this is implausible. By contrast in our complex, five of the functional groups form direct hydrogen bonds in addition to extensive van der Waals interactions with residues in AbFolD that are highly conserved in orthologues and there are no intramolecular steric clashes.

Fig. 5.

Superposition of LY354899 (blue), 9L9 (green) from the AbFolD complex crystal structures and the structure assigned as LY374571 (black) bound in the human DHCH structure.

A key step in the synthetic procedure is the reaction of 6-hydroxy-2,4,5-triaminopyrimidine with ethyl 4-iso-cyanatobenzoate. To make the compound that we assigned, the coupling would have occurred at the amine (N5) adjacent to the pyridone oxygen. Of the three amines on the starting material, this might be predicted to be the most nucleophilic. The least nucleophilic, and the position where a reaction to produce LY374571 is required, is probably at N4. We therefore conclude there is a strong possibility that the compound previously assigned as LY374571 is the compound we have characterized in the present study.

As a result of synthesizing the ‘wrong’ compound, we next attempted (several times) to produce LY374571 using different approaches, principally by changing the starting material in an attempt to achieve selective addition onto the ethyl-4 isocyanatobenzoate. On each occasion, the synthesis failed or produced mixtures, with the predominant species being the compound described. Further synthetic protocols would have to be tried to obtain the ‘real’ LY374571.

Reaction mechanism

The inhibitors that we have characterized represent good mimics for the intermediate, N5,N10-methenylTHF, and the reaction product, N10-formylTHF, and allow us to comment on aspects of the enzyme action. The enzyme FolD possesses both the Rossmann-fold and the YxxxK motif typical of the small dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) family. In the SDR family, the lysine interacts with the ribose and serves to position the nicotinamide, whereas the tyrosine provides a hydroxyl group to participate directly in catalysis [20]. In AbFolD, the residues in the motif are Tyr49 and Lys53 but, because the substrate is placed between them and the cofactor, preventing any direct interaction, then their contribution to the mechanism is distinct from that in the SDR family. The lysine, which is in a mainly hydrophobic environment as a result of the positions of Ile266, Val250, Leu269, Ile270, Ile95, Ala56, Tyr49 and Leu35 (not shown) likely acts in conjunction with Gln97 to provide the right environment to position and activate substrate, and to support hydride abstraction by NADP+ for the dehydrogenase activity. Although, in our structures, the nicotinamide is disordered and absent from the model, a superposition of human DHCH (PDB code: 1DIB) [12] with an ordered cofactor on AbFolD ligand complexes placed the reactive C4 group within 3 Å of the position where hydride abstraction occurs, therefore implying that the dehydrogenase reaction is a relatively simple process. This is consistent with previous studies [12].

However, there is speculation [12,21,22] that, for a bifunctional process to occur, the pteridine had to change orientation after hydride abstraction. It was suggested that a channelling process was necessary to support the cyclohydrolase reaction. The structural data reported in the present study (Fig. 3B) suggest that this may not be required. The complex with LY354899 in particular reveals ordered water molecules binding near to where hydrolysis occurs. Several functional groups (e.g. provided by Lys53, Asp120 and Thr265) are available to contribute by activating water to participate in the second cyclohydrolase reaction. Less likely but still worthy of mention is the possibility that Tyr49 might undergo a conformational change, similar to that observed in going from binary to ternary complex, and provide a hydroxyl group to help activate a water in support of the cyclohydrolase reaction.

Concluding remarks

Structures of AbFolD have been determined in the presence of partially disordered NADP+ and two potent inhibitors, both of which are reaction intermediate mimics. The structures clearly resolve the details of molecular recognition of these inhibitors with the target enzyme. These structural data contribute new information on the reaction mechanism and support the assignment of an alternative structure for a previously studied FolD inhibitor, LY374571.

Experimental procedures

Recombinant protein production

The A. baumannii folD gene, encoding the bifunctional DHCH, was identified in UniProtKB (http://www.uniprot.org accession number D0CBC8). The gene (locus tag: EEX03016.1) was amplified from genomic DNA (American Type Culture Collection strain 19606) with primers carrying XhoI and BamHI restriction sites (bold), respectively: 5′-CTC-GAG-ATG-GCA-TTG-GTT-TTA-GA-3′, 5′-GGA-TCC-TTA-ACC-TAA-AGC-TTT-TTT-TTC-AG-3′. The PCR product was ligated into pCR-BluntII-TOPO vector using the Zero Blunt TOPO PCR cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) before excising the gene and subsequent ligation into a modified pET15b vector (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA). This vector contains a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease recognition sequence in place of thrombin (pET15bTEV), resulting in the product carrying an N-terminal hexa-histidine tag (His-tag), which is cleavable with TEV protease. The recombinant plasmid was amplified in XL-1 blue E. coli, then heat-shock transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) for protein production. The integrity of the gene sequence was verified by the University of Dundee Sequencing Service.

E. coli harbouring the expression plasmid were cultured at 37 °C, with shaking at 200 rpm, in auto-induction media [23] supplemented with 50 mg·L−1 carbenicillin for approximately 3 h until D600 of 0.8 was reached. The temperature was subsequently reduced to 21 °C for a further 22 h, before the cells were harvested by centrifugation (3500 g for 30 min at 4 °C). The cells were resuspended into a lysis buffer (buffer A: 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 250 mm NaCl, 25 mm imidazole) containing DNAse I (200 μg) and an EDTA-free protease-inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Cells were lysed using a French press at 16 000 Ψ and the solution clarified by centrifugation (50 000 g for 30 min at 4 °C). The supernatant was filtered, loaded onto a HisTrap HP 5-mL column (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) pre-charged with Ni2+ and the His-tagged AbFolD eluted using a imidazole gradient of 25 mm to 1 m. The fractions were analyzed using SDS/PAGE and those found to contain AbFolD were pooled. His-tagged TEV protease (1 mg per 20 mg of FolD) was added and the mixture dialyzed against 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 250 mm NaCl for 3 h at room temperature. Another passage through a His-Trap column separated cleaved AbFolD from TEV protease, the cleaved His-tag peptide and uncleaved His-tagged AbFolD. The sample of AbFolD was then applied to a Superdex 200 26/60 column (GE Healthcare), pre-equilibrated in buffer A minus imidazole. The protein eluted as a single species with a mass of approximately 60 kDa corresponding to a dimer. The sample was dialysed into 100 mm Pipes (pH 7.0) and 150 mm NaCl and concentrated to 20 mg−1·mL−1 using a 10-kDa MWCO Amicon Ultra devices (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Protein concentration was determined spectrophotometrically using a theoretical extinction coefficient of 10 220 m−1·L−1·cm−1 at 280 nm calculated using protparam [24]. The high level of protein purity was confirmed by SDS/PAGE and MALDI-TOF MS (FingerPrint Proteomic Facility, University of Dundee). The yield of purified protein was approximately 60 mg−1·L−1 of bacterial culture. Protein was diluted to 10 mg−1·mL−1 and used fresh for crystallization trials or to 2 mg−1·mL−1 and supplemented with 10% glycerol and then flash frozen in liquid nitrogen for storage before kinetic characterization.

Crystallization

Crystallization conditions were screened with the sitting drop vapour diffusion method in 96-well plates using a Phoenix liquid handling system (Rigaku; Art Robins Instruments, Mountain View, CA, USA) and commercially available screens. Optimized conditions were achieved using hanging drop vapour diffusion methods with drops consisting of 2 μL of protein solution and 2 μL of reservoir solution. Crystals of the AbFolD were obtained using a mixture of 2 μL of reservoir solution (0.1 m Bis-Tris, pH 5.5, 25% poly(ethylene glycol) 3350, 0.2 m MgCl2 and 2% dioxane) and with an equal volume of protein solution (AbFolD at 10 mg−1·mL−1 and 10 mm NADP+). Monoclinic crystals (350 × 200 × 50 μm), grew after approximately 5 days at room temperature. Crystals of the ternary complexes with the poorly soluble inhibitors were obtained after incubating the protein solution for 4 h with solid compounds in vast molar excess, before clarification by centrifugation and then using the supernatant for crystallization. Crystals of the AbFolD ternary complexes were obtained using a mixture of 0.75 μL of reservoir solution [0.1 m Bis-Tris, pH 5.5, 20% poly(ethylene glycol) 3350, 0.2 m MgCl2 and 2% dioxane] and 1.5 μL volume of protein solution (AbFolD at 5 mg−1·mL−1 and 10 mm NADP+). The crystals were slightly smaller (200 × 100 × 100 μm). Crystals were transferred to a solution containing the reservoir solution adjusted to incorporate 20% glycerol before flash freezing at −173°C.

Data collection and structure solution

Data for the ternary complex crystals were collected in-house with a Micromax 007 rotating anode generator (λ = 1.5418 Å) and R-AXIS IV++ dual image plate detector (Rigaku). Data for the binary complex were collected at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF, Grenoble, France) at beam line ID29 (λ = 0.981 Å) using an ADSC Q315r charge-coupled device detector. Processing and scaling of the data were carried out using mosflm [25] and scala [26]. The crystals are isomorphous (Table 2). There are two subunits in the asymmetric unit with Vm values of 2.44 Å3·Da−1 and a bulk solvent content of approximately 50%. The initial NADP+ binary complex structure was solved by molecular replacement using phaser [27]. A subunit of the E. coli apo structure (PDB code: 1B0A) [13] provided the search model after it was changed to poly-alanine in chainsaw [28]. Refinement of the ternary complexes was initiated using the binary complex model. Refinement was carried out using refmac5 [29] interspersed with electron-density and difference density map inspection, model manipulation and the incorporation of solvent and ligands using coot [30]. The two monomers in the asymmetric unit were treated independently during refinement. translation/liberation/screw analysis [31] was applied to the ternary complex structures but not the binary complex, where anisotropic refinement of thermal parameters was carried out as a result of the high resolution of the available data. Crystallographic statistics are provided in Table 2. Model geometry was analyzed using molprobity [32], whereas rmsd values comparing structures were obtained from lsqkab [33]. Figures were prepared with pymol [34] and chemdraw (CambridgeSoft, Cambridge, MA, USA). Amino acid sequence alignments were carried out using muscle [35] and visualized in aline [36].

Kinetic characterization

The substrates (6R,S)-5,10-methylene-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrofolic acid and (6R,S)-5,10-methenyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrofolic acid were purchased from Schirks Laboratories (Jona, Switzerland). Two compounds were identified as potential inhibitors of AbFolD: 5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-N5,N10-carbonylfolic acid and (2R)-2-[(4-{[(2,5-diamino-6-hydroxypyrimidinyl)carbamoyl]amino}phenyl)formamido] pentanedioic acid. These compounds, previously developed by Lilly and assigned the names LY354899 and LY374571, respectively, were synthesized in accordance with reported methods [12,37,38] and analyzed by NMR, MS and HPLC (Figs S3-S6, Doc. S1). All of the chemicals utilized were of analytical grade.

The enzyme was assayed using a protocol reported previously [39] with modifications. Km values for the dehydrogenase activity with N5,N10-methylene tetrahydrofolate were determined at 27 °C in 25 mm Mops (pH 7.3), 30 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, using between 2.5 μm and 1 mm substrate (dissolved in 20 mm NaOH). The reaction was initiated with addition of 1 mm NADP+, whereas assays for the cofactor were fixed at 250 μm N5,N10-methylene tetrahydrofolate and between 2.5 μm and 1 mm NADP+. Assays were run in duplicate in 0.5-mL volumes in acrylic cuvettes and were stopped with an equal volume of 1 m HCl after 2 min. Background rates were determined with pre-stopped reactions. Concentrations of intermediate were determined using the extinction co-efficient of 24.9 mm−1·cm−1 at 350 μm for acidified solutions of the intermediate [40]. Unlike previously described inhibition studies [12,18], the substrate was used directly rather than being formed from tetrahydrofolate and formaldehyde during the reaction.

The assays for cyclohydrolase activity with N5,N10-methenyl tetrahydrofolate were performed at 27 °C in 25 mm Mops (pH 7.3), 30 mm 2-mercaptoethanol and between 0.5 and 100 μm substrate (dissolved in 10 mm HCl) and started by the addition of the enzyme. Assays were in duplicate in 1-mL volumes in acrylic cuvettes with the hydrolysis of N5,N10 methenyl tetrahydrofolate measured as a decrease at 355 nm and a background rate determined in enzyme free assays. Concentrations of the substrate were calculated using the extinction coefficient of 25.1 mm−1·cm−1 [39]. Inhibition studies were carried out at the substrate Km using at least ten concentrations of the inhibitors (dissolved in 100% dimethylsulfoxide) with the final dimethylsulfoxide concentrations in the assays never exceeding 1%. Activities for the inhibition assays are expressed as the percentage of a dimethylsulfoxide control. Absorbance for both assays was measured using a Shimadzu UV-2450 (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan) and data were plotted using sigmaplot, version 11 (Systat Software Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Supplementary Material

This supplementary material can be found in the online version of this article.

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer-reviewed and may be re-organized for online delivery, but are not copy-edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Acknowledgements

We thank Natalia Shpiro for the custom synthesis of inhibitors, Colin Gibson for synthetic chemistry input, David Norman for discussions on NMR, our colleagues in the Aeropath project and staff at the ESRF for excellent support. This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust (grants 082596 and 083481) and the European Commission Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013; Aeropath).

Abbreviations

- CH

N5,N10-methenyltetrahydrofolate cyclohydrolase

- DH

N5,N10-methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase

- DHCH

N5,N10 methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- SDR

small dehydrogenase/reductase

- TEV

tobacco etch virus

- THF

tetrahydrofolate.

Footnotes

Database: The coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession numbers:4B4U, 4B4V and 4B4W.

References

- 1.Dijkshoorn L, Nemec A, Seifert H. An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:939–951. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rice LB. The clinical consequences of antimicrobial resistance. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12:476–481. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falagas ME, Bliziotis IA. Pandrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria: the dawn of the post-antibiotic era? Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;29:630–636. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perez F, Hujer AM, Hujer KM, Decker BK, Rather PN, Bonomo RA. Global challenge of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3471–3484. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01464-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. Antibiotics for emerging pathogens. Science. 2009;325:1089–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.1176667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunter WN. Structure-based ligand design and the promise held for antiprotozoan drug discovery. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:11749–11753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800072200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eadsforth TC, Gardiner M, Maluf FV, McElroy S, James D, Frearson J, Gray D, Hunter WN. Assessment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa N5,N10-methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase-cyclohydrolase as a potential antibacterial drug target. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e3597. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eadsforth TC, Cameron S, Hunter WN. The crystal structure of Leishmania major N(5),N(10)-methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase and assessment of a potential drug target. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2012;18:178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lucock M. Folic acid: nutritional biochemistry, molecular biology, and role in disease processes. Mol Genet Metab. 2000;71:121–138. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2000.3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen KE, MacKenzie RE. Mitochondrial one-carbon metabolism is adapted to the specific needs of yeast, plants and mammals. Bioessays. 2006;28:595–605. doi: 10.1002/bies.20420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allaire M, Li Y, MacKenzie RE, Cygler M. The 3-D structure of a folate-dependent dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase bifunctional enzyme at 1.5 Å resolution. Structure. 1998;6:173–182. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt A, Wu H, MacKenzie RE, Chen VJ, Bewly JR, Ray JE, Toth JE, Cygler M. Structures of three inhibitor complexes provide insight into the reaction mechanism of the human methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6325–6335. doi: 10.1021/bi992734y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen BW, Dyer DH, Huang JY, D’Ari L, Rabinowitz J, Stoddard BL. The crystal structure of a bacterial, bifunctional 5,10 methylene-tetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase. Protein Sci. 1999;8:1342–1349. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.6.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monzingo AF, Breksa A, Ernst S, Appling DR, Robertus JD. The X-ray structure of the NAD-dependent 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1374–1381. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.7.1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Ari L, Rabinowitz JC. Purification, characterization, cloning, and amino acid sequence of the bifunctional enzyme 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/5,10-methenyltetrahydrofolate cyclohydrolase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:23953–23958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wohlfarth G, Geerlings G, Diekert G. Purification and characterization of NADP+ dependent 5,10 methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase from Peptostreptococcus productus. Marburg. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1414–1419. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.4.1414-1419.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee WH, Sung MW, Kim JH, Kim YK, Han A, Hwang KY. Crystal structure of bifunctional 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase from Thermoplasma acidophilum. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2011;406:459–463. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.02.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murta SMF, Vickers TJ, Scott DA, Beverley SM. Methylene tetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase and the synthesis of 10-CHO-THF are essential in Leishmania major. Mol Microbiol. 2009;71:1386–1401. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06610.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark JE, Ljungdahl LG. Purification and properties of 5,10-methenyltetrahydrofolate cyclohydrolase from Clostridium formicoaceticum. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:3833–3836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gourley DG, Schuttelkopf AW, Leonard GA, Luba J, Hardy LW, Beverley SM, Hunter WN. Pteridine reductase mechanism correlates pterin metabolism with drug resistance in trypanosomatid parasites. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:521–525. doi: 10.1038/88584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pawelek PD, Allaire M, Cygler M, MacKenzie RE. Channeling efficiency in the bifunctional methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase domain: the effects of site-directed mutagenesis of NADP binding residues. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1479:59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(00)00058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sundararajan S, MacKenzie RE. Residues involved in the mechanism of the bifunctional methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase-cyclohydrolase. The roles of glutamine 100 and aspartate 125. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:18703–18709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200127200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Studier FW. Protein production by auto-induction in high density shaking cultures. Protein Expr Purif. 2005;41:207–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gasteiger E, Gattiker A, Hoogland C, Ivanyi I, Appel RD, Bairoch A. ExPASy: the proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3784–3788. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leslie AG. The integration of macromolecular diffraction data. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:48–57. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905039107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stein N. CHAINSAW: a program for mutating pdb files used as templates in molecular replacement. J Appl Crystallogr. 2008;41:641–643. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott W, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Painter J, Merritt EA. Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:439–450. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906005270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen V, Arendall W, Headd J, Keedy D, Immormino R, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kabsch W. A solution for the best rotation to relate two sets of vectors. Acta Crystallogr A. 1976;32:922–923. [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeLano DL. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. DeLano Scientific; San Carlos, CA, USA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bond CS, Schuttelkopf AW. ALINE: a WYSIWYG protein-sequence alignment editor for publication-quality alignments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2009;65:510–512. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909007835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Temple C, Jr, Bennett LL, Jr, Rose JD, Elliott RD, Montgomery JH. Synthesis of pseudocofactor analogs as potential inhibitors of the folate enzymes. J Med Chem. 1982;25:161–166. doi: 10.1021/jm00344a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tonkinson JL, Habeck LL, Toth JE, Mendelsohn LG, Bewley J, Shackelford KA, Gates SB, Ray J, Chen VJ. The antiproliferative and cell cycle effects of 5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-N5,N10-carbonylfolic acid, an inhibitor of methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase, are potentiated by hypoxanthine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;287:315–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan L, Drury E, MacKenzie R. Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase-methenyltetrahydrofolate cyclohydrolase-formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase A multifunctional protein from porcine liver. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:1117–1121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rabinowitz JC, Pricer WE., Jr Formimino-tetrahydrofolic acid and methenyltetrahydrofolic acid as intermediates in the formation of N10-formyltetrahydrofolic acid. J Amer Chem Soc. 1956;78:5702–5704. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.