Abstract

Objective

To estimate the effect of antenatal glucocorticoid administration on fetal lung maturity in pregnancies with known fetal lung immaturity between the 34th and 37th weeks of gestation.

Study Design

Pregnancies between 340/7-366/7 weeks undergoing amniocentesis to determine fetal lung maturity were targeted. Women with negative results (TDx-FLM-II < 45 mg/g) were randomized to intramuscular (IM) glucocorticoid injection or no treatment. A repeat TDx-FLM-II test was obtained one week after enrollment.

Results

32 women who met inclusion criteria were randomized. Seven women delivered within a week of testing for fetal lung maturity, and were excluded from the analysis. Ten received glucocorticoid and 15 did not. Women assigned to glucocorticoids had a mean increase TDx-FLM-II in one week of 28.37 mg/g. Women assigned to no-treatment had an increase of 9.76 mg/g (p <0.002).

Conclusion

A single course of IM glucocorticoids after 34 weeks in pregnancies with documented fetal lung immaturity significantly increases TDx- FLM-II.

Keywords: amniocentesis, fetal lung maturity, steroids

Introduction

Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) is a major cause of morbidity in the newborn, and is ranked as one of the leading causes of infant deaths in the United States(1). It has been demonstrated that treatment with corticosteroids results in a reduction in the rate of RDS in pregnancies at risk to deliver preterm(2). Treatment with corticosteroids have also been suggested to reduce the rates of intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, neonatal mortality and systemic infection in the first 48 hours of life(2). Because of these benefits, current recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists call for a single course of corticosteroids to all pregnant women between 24 and 34 weeks of gestation who are at risk for preterm delivery(3).

While it is accepted that enhancement of pulmonary function via antenatal steroids is recommended for pregnancies at risk for preterm birth at less than 34 weeks, less is known about the effects of steroids among women at more advanced gestational ages(4). A meta-analysis of published randomized trials on antenatal steroid therapy indicated limited number of patients participating after 34 weeks(4). Even though the incidence of RDS is lower after 34 weeks(5), late-preterm infants (defined as birth between 340/7-366/7) are at higher risk of complications as compared to term infants(6) and the benefit of steroids for enhancement of fetal lung maturity during this period remains to be determined.

The assessment of fetal lung maturity is useful for determining the timing of delivery in patients with complicated pregnancies(7). Amniocentesis is commonly performed after 34 weeks in cases where continuing pregnancy may present substantial maternal and fetal risks. Examples of these complicated pregnancies include a history of bleeding placenta previa, a history of a previous classical cesarean delivery, a history of previous uterine surgery, or in diabetic patients with suboptimal metabolic control. While the interpretation of a mature fetal lung maturity test is straightforward, there is no consensus on the timing and course of action after an immature result. In our previous analysis we assessed the weekly increment of TDx-FLM II between 31 and 38 weeks and reported an average 14.4 mg/g per week (95%CI 12.3-16.5) increase(8). The effect of steroids among women who have a negative fetal lung maturity test after 34 weeks has not been sufficiently addressed. Methods to accelerate pulmonary maturity in cases of documented fetal pulmonary immaturity after 34 weeks would potentially reduce the likelihood of RDS when preterm delivery is indicated. The purpose of our study was to test the hypothesis that antenatal glucocorticoid administration in pregnancies with known fetal lung immaturity between the 34th and 37th weeks of gestation might accelerate fetal lung maturity.

Materials and Methods

This randomized controlled study was conducted at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri between May 2003 and May 2008. The Human Studies Committee at Washington University School of Medicine approved the protocol and informed consent was obtained from eligible patients. Women with singleton gestations between 340/7-366/7 weeks with an immature TDx-FLM-II test (< 45 mg/g) after a clinically indicated amniocentesis to test for fetal lung maturity were invited to participate. Gestational age was calculated based on the last menstrual period (LMP) and correlated to an ultrasound measurement. The LMP was used to assign the gestational age in cases where the ultrasound correlated within ± 7 days. For discrepancies between the LMP and the ultrasound dating > 7 days, the ultrasound-assigned gestational age was utilized. For patients where the LMP was uncertain, the ultrasound at ≤ 20 weeks was used for gestational age assignment.

Patients excluded were those with multiple gestations, ruptured membranes, uncertain gestational ages, steroid treatment previously in the current pregnancy, delivery before completion of the steroid course and those who were unwilling or unable to comply with the study protocol. Block randomization was performed, which ensured equal numbers of steroid and no steroid assignments, with sealed envelopes twice the target number of subjects. Eligible patients were consented and randomized into either treatment group or the no-treatment group.

The treatment group received corticosteroids, either betamethasone 12 mg intramuscular (IM) injection every 24 hours for two doses or dexamethasone 6 mg, IM every 12 hours for 4 doses. This treatment is identical to those given to patients between 24-34 weeks gestation at risk for preterm delivery(3). Both the treatment and the no-treatment group underwent a repeat test for fetal lung maturity seven days after the initial sampling. This was performed by either amniocentesis or, if it occurred after seven days, directly at the time of delivery. Patients undergoing cesarean delivery had amniotic fluid sampled at the time of their hysterotomy. Patients delivering vaginally had fluid taken from a vaginal pool at the time of artificial rupture of membranes(7). Patients were excluded for preterm delivery in less than seven days after the initial amniocentesis.

Whereas different laboratory markers, lecithin-to-sphingomyelin ratio (L/S), presence of phosphatidylglycerol (PG), lamellar body count, and surfactant-to-albumin ratio (TDx-FLM-II)(7, 9-14), may be used to determine fetal lung maturity, the TDx-FLM-II is the test of choice at our institution. When fetal lung maturity is defined as > 45 mg/g, we found 100% sensitivity (no cases of RDS) and 90% specificity for assessment of a mature result(14). The TDx-FLM-II test was found to be more sensitive with improved negative predictive values compared to L/S(13) and had a more rapid turnaround time and lower cost compared to L/S and PG.

Our primary outcome was the percent with positive lung maturity test results (TDx-FLM-II > 45 mg/g) in one week between the two groups. Secondary outcomes included increase in TDx-FLM-II value between the two groups as well as neonatal ICU admissions, duration of ICU stay, neonatal hyaline membrane disease and any maternal complications associated with corticosteroid administration. A sample size calculation was performed for the primary outcome variable based on the results of earlier studies evaluating amniotic fluid indices of fetal lung maturity. One study of amniotic fluid fetal pulmonary phospholipids revealed a spontaneous weekly conversion of 18% from an immature to a mature result between 34 and 37 weeks gestation(15). A meta-analysis showed a marked reduction in RDS in infants delivered between 24 hours and 7 days after corticosteroid administration (OR for RDS 0.35, 95% CI 0.26 – 0.46). This was extrapolated to a 51% mature result in the steroid group compared to 18% in the control group. Assuming an alpha of 0.05 for a two-tailed test (given steroids could increase or potentially decrease TDx-FLM-II) and a power of 0.8, a sample size of 38 women was required in each arm of the study. Data were analyzed with STATA version 9.0 using a paired t-test, Fischer's exact test and Chi-square test where appropriate. P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

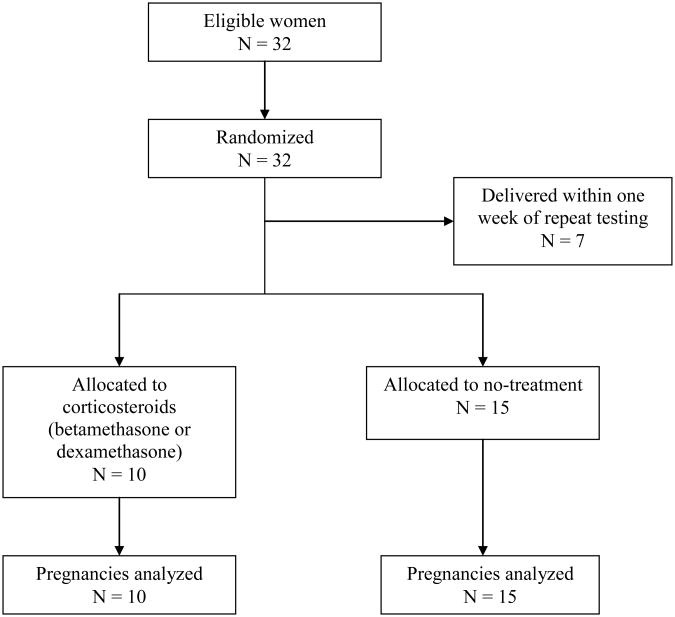

Thirty-two women who met the inclusion criteria were randomized. Thirteen patients were randomized to the steroid arm and 19 patients were randomized to the no-treatment arm. Seven women, three in the steroid arm and four in the no-treatment group, delivered within 7 days of their initial testing for fetal lung maturity and were therefore excluded from the analysis. Ten women receiving IM steroids and 15 receiving no-treatment were analyzed (Figure 1). There were no significant differences between the two groups with respect to patient age, gestational age at first amniocentesis, race and delivery mode (Table 1). There were more women with diabetes and hypertension in the no-treatment group but this was not statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Randomization, treatment and follow-up of patients.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the study population.

| Steroids (n=10) | No-treatment (n=15) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Maternal age (mean) | 26.6 ± 4.7 | 25.4 ± 5.6 | 0.58 |

|

| |||

| Gestational age at first amniocentesis (weeks) | 35.2 + 0.78 | 35.4 ± 0.88 | 0.75 |

|

| |||

| Maternal Race (%) | |||

| Black | 7 | 11 | |

| White | 2 | 3 | 0.96 |

| Other | 1 | 1 | |

|

| |||

| Indication for amniocentesis (%) | |||

| history of 2 or more prior LTCS | 4 (40%) | 6 (40%) | 0.28 |

| history of classical cesarean | 1 (10) | 4 (27) | |

| history of previous uterine surgery | 2 (20) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 3 (30) | 5 (33) | |

|

| |||

| Maternal Diabetes (%) | 0 | 4 | 0.11 |

|

| |||

| Hypertension (%) | 0 | 3 | 0.20 |

|

| |||

| Delivery mode (%) | |||

| Cesarean | 10 (100%) | 13 (87%) | 0.35 |

| Vaginal | 0 | 2 | |

Using a TDx-FLM-II of > 45 mg/g to indicate fetal pulmonary maturity, 5 of 10 patients (50%) in the corticosteroid arm had a mature profile in one week whereas only four of 15 patients (27%) in the no-treatment arm had mature fetal lung profiles in one week though the differences between the two groups were not statistically significant (p 0.40).

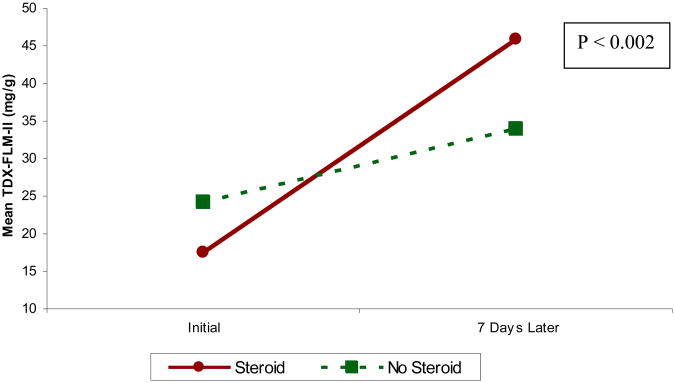

Women assigned to steroid treatment had an initial mean TD-FLM-II of 17.49 mg/g (95% CI 14.04-20.94). The mean TDx-FLM-II following one week in this group was 45.86 mg/g (95% CI 35.21-56.51).

Women assigned to no-treatment had an initial mean TDx-FLM-II of 24.19 mg/g (95% CI 18.72-29.67). The mean TDx-FLM-II following one week in this group was 33.95 (95% CI 26.69-41.22). The difference in the mean TDx-FLM-II increase in one week between the steroid (28.37 mg/g, 95% CI 18.94-37.8) and no-treatment groups (9.76 mg/g, 95% CI 5.41-14.11) was statistically significant (p<0.002, Figure 2).

Figure 2. Mean TDx-FLM-II increase in one week.

There were four diabetic patients and all were randomized to the no-treatment arm. Analysis of the non-diabetic patients randomized to the no-treatment arm (N = 11) revealed a one-week TDx-FLM-II increase of 9.86 mg/g (p 0.0012 when compared to patients treated with corticosteroids).

There were two admissions of newborns to the NICU secondary to respiratory distress requiring intubations, with both of these in the no-treatment group. The first occurred in a patient with a negative fetal lung maturity profile after one week (TDx-FLM-II 17.5 mg/g) who subsequently went into labor. The baby was intubated at delivery, extubated on day of life 2 and had an 8-day NICU stay. The second NICU admission followed an emergent cesarean delivery after a cord prolapse during an elective labor induction following a mature fetal lung maturity profile. This occurred in a diabetic pregnancy with a TDx-FLM-II of 55.3 mg/g. The infant was extubated after 24 hours and had a total NICU stay duration of 5 days. There were no maternal complications associated with treatment.

The study was stopped due to difficulty in patient recruitment. However, post-hoc analysis revealed a 99% power to detect a difference in the weekly TDx-FLM-II increase between the steroid and the no-treatment groups. The power calculation was performed using a two-group Satterthwaite t-test with a 0.05 two-sided significance level with unequal sample size in each group.

Comment

The results of our study show that the administration of corticosteroids between 340/7-366/7 weeks gestation can significantly increase the TDx-FLM-II value in one week. The ability to enhance the fetal lung maturity would potentially allow delivery in situations where expectant management implies significant risks. Patients with a history of a prior classical cesarean or patients with placenta previa are just two specific examples where the increased risk of morbidity could be avoided by earlier delivery.

Though the study was stopped early, the primary outcome of fetal pulmonary maturity (TDx-FLM-II) was seen more frequently in patients that received steroids (50%) compared to no-treatment (27%) though the differences between the groups were not statistically significant. A statistically significant difference between the groups was seen in the mean weekly increase in TDx-FLM-II values providing us with an objective measurement of the effects of corticosteroid administration. It is worth noting that despite having a lower initial mean TDx-FLM-II value, the group receiving steroids had both a higher increase in TDx-FLM-II in one week as well as a higher percentage of mature profiles (TDx-FLM-II > 45 mg/g).

There is a consensus that glycemic control in the diabetic patient influences fetal lung maturity.(7) Pregnancies complicated by insulin-dependent diabetes are 20 times more likely to be associated with neonatal RDS as compared to normal pregnancies(16). A delay in phospholipid production and phosphotidylglycerol appearance in the amniotic fluid has been described(17). Though patients were randomized to treatment with steroids and no-treatment, there was a disproportionate allocation of diabetics to the no-treatment group. It is interesting to note that the difference between the study groups still persists with the censuring of the results of the diabetic patients. This further strengthens the finding of a difference in the mean TDx-FLM-II increase in one week between the two study arms.

The study was stopped due to difficulty in patient recruitment. The changing practice of amniocentesis at later gestational ages contributed to smaller numbers of patients meeting the inclusion criteria of gestational age 340/7-366/7 weeks. Even though the pre-specified sample size was not reached, post-hoc analysis revealed a 99% power to detect a difference in the treatment groups.

The impact of our study reveals that even in the late preterm period, corticosteroids can accelerate measurements of fetal lung maturity. Despite sample size limitations our data suggest that women with a negative fetal lung maturity test between the 34th-37th week can benefit from a single course of steroids. The potential to decrease neonatal morbidity is suggested by these results, and warrants further research in this area.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Allsworth was supported in part by a Clinical and Translational Science Awards (UL1RR024992), and by Grant Number KL2RR024994 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. Information on NCRR is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/. Information on Re-engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise can be obtained from http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/clinicalresearch/overview-translational.asp

Footnotes

This research was presented at the 29th Annual Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Meeting in San Diego, CA.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Anthony Shanks, Email: shanksa@wudosis.wustl.edu, Maternal-Fetal Medicine Fellow, Washington University in St. Louis, Box 8064, 660 South Euclid, St. Louis, MO 63110 USA, 314-362-7300.

Gilad Gross, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri.

Tammy Shim, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri.

Jenifer Allsworth, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri.

Ibrahim Bildirici, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri.

Yoel Sadovsky, Magee-Womens Reseach Institute, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

References

- 1.Martin JA, Kung HC, Mathews TJ, Hoyert DL, Strobino DM, Guyer B, et al. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2006. Pediatrics. 2008 Apr;121(4):788–801. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts D, Dalziel S. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2006;3:CD004454. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004454.pub2. Online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 402. Antenatal corticosteroid therapy for fetal maturation. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2008 Mar;111(3):805–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318169f722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crowley PA. Antenatal corticosteroid therapy: a meta-analysis of the randomized trials, 1972 to 1994. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1995 Jul;173(1):322–35. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robertson PA, Sniderman SH, Laros RK, Jr, Cowan R, Heilbron D, Goldenberg RL, et al. Neonatal morbidity according to gestational age and birth weight from five tertiary care centers in the United States, 1983 through 1986. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1992 Jun;166(6 Pt 1):1629–41. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91551-k. discussion 41-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ACOG committee opinion No. 404 April 2008. Late-preterm infants. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2008 Apr;111(4):1029–32. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817327d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 97. Fetal lung maturity. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2008 Sep;112(3):717–26. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318188d1c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bildirici I, Moga CN, Gronowski AM, Sadovsky Y. The mean weekly increment of amniotic fluid TDx-FLM II ratio is constant during the latter part of pregnancy. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2005 Nov;193(5):1685–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.03.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gluck L, Kulovich MV, Borer RC, Jr, Brenner PH, Anderson GG, Spellacy WN. Diagnosis of the respiratory distress syndrome by amniocentesis. 1971. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1995 Aug;173(2):629. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90293-7. discussion 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garite TJ. Fetal maturity testing. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 1987 Dec;30(4):985–91. doi: 10.1097/00003081-198712000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashwood ER, Palmer SE, Taylor JS, Pingree SS. Lamellar body counts for rapid fetal lung maturity testing. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1993 Apr;81(4):619–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis PS, Lauria MR, Dzieczkowski J, Utter GO, Dombrowski MP. Amniotic fluid lamellar body count: cost-effective screening for fetal lung maturity. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1999 Mar;93(3):387–91. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00416-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hagen E, Link JC, Arias F. A comparison of the accuracy of the TDx-FLM assay, lecithin-sphingomyelin ratio, and phosphatidylglycerol in the prediction of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1993 Dec;82(6):1004–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fantz CR, Powell C, Karon B, Parvin CA, Hankins K, Dayal M, et al. Assessment of the diagnostic accuracy of the TDx-FLM II to predict fetal lung maturity. Clinical chemistry. 2002 May;48(5):761–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore TR. A comparison of amniotic fluid fetal pulmonary phospholipids in normal and diabetic pregnancy. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2002 Apr;186(4):641–50. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.122851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robert MF, Neff RK, Hubbell JP, Taeusch HW, Avery ME. Association between maternal diabetes and the respiratory-distress syndrome in the newborn. The New England journal of medicine. 1976 Feb 12;294(7):357–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197602122940702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulovich MV, Gluck L. The lung profile. II. Complicated pregnancy. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1979 Sep 1;135(1):64–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]