Abstract

Background. Tianma Gouteng Yin (TGY) is widely used for essential hypertension (EH) as adjunctive treatment. Many randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of TGY for EH have been published. However, it has not been evaluated to justify their clinical use and recommendation based on TCM zheng classification. Objectives. To assess the current clinical evidence of TGY as adjunctive treatment for EH with liver yang hyperactivity syndrome (LYHS) and liver-kidney yin deficiency syndrome (LKYDS). Search Strategy. 7 electronic databases were searched until November 20, 2012. Inclusion Criteria. RCTs testing TGY combined with antihypertensive drugs versus antihypertensive drugs were included. Data Extraction and Analyses. Study selection, data extraction, quality assessment, and data analyses were conducted according to the Cochrane standards. Results. 22 RCTs were included. Methodological quality was generally low. Except diuretics treatment group, blood pressure was improved in the other 5 subgroups; zheng was improved in angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), calcium channel blockers (CCBs), and “CCB + ACEI” treatment groups. The safety of TGY is still uncertain. Conclusions. No confirmed conclusion about the effectiveness and safety of TGY as adjunctive treatment for EH with LYHS and LKYDS could be made. More rigorous trials are needed to confirm the results.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide [1, 2]. High blood pressure (BP) is the major independent risk factors for CVD [3–5]. Therefore, hypertension and blood-pressure-related disease have become an emerging epidemic and important worldwide public-health challenge [6–12]. Oral antihypertensive drugs are a milestone in the therapy of hypertension and other CVDs. However, the control rates of hypertension are still far from optimal currently [13, 14]. What is more, although treated with intensive medication, uncontrolled hypertension related symptoms (including headache, dizziness, and fatigue) and the side effects of antihypertensive drug therapy (including headache, flushing, dry cough, edema, and sexual dysfunction) are still the major problems confronting modern medicine [15–18]. Effective treatment of hypertension is limited by availability, cost, and adverse effects of conventional western medicine treatment. Thus, a certain proportion of the population has turned to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), including traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) [19–23], for lowing BP and improving its related symptoms worldwide [24, 25].

Within Asia, TCM is widely used about 3,000 years ago [26–28]. It has formed a unique theoretical system and control methods [29–31]. TCM zheng (also called as syndrome or zheng differentiation or pattern classification) is the basic unit and the key concept in TCM theory [32–35]. Currently combination of zheng classification and biomedical diagnosis has become a hot topic both in diagnostics and treatment for the basic and clinical research [36–39]. Recently, increasing number of clinical trials and systematic reviews (SRs) showed that, as compared to antihypertensive therapy alone, Chinese herbal formula combined with antihypertensive drugs (also known as combination therapy) appear to be more effective in improving BP and symptoms in hypertensive patients with certain syndrome [40–43]. There is no doubt that, with more and more rigorous research evidences of effectiveness and safety about combination therapy, clinical studies linking TCM zheng classification and biomedicine diagnosis will lead to personalized therapeutic strategies and innovation in medical sciences [44, 45].

According to TCM theory, liver yang hyperactivity syndrome (LYHS) and liver-kidney yin deficiency syndrome (LKYDS) are the most important and common TCM zheng of essential hypertension (EH) [46]. LYHS is characterized by vertigo, tinnitus, headache, flushing, red eyes, irritability, insomnia, lassitude in lion and legs, bitter mouth, red tongue, and wiry pulse. LKYDS is always characterized by dizziness, tinnitus, headache, low fever, flushing, burning sensation of five centres, hypochondriac pain, hypopsia, lassitude in lion and legs, red tongue with scanty coating, and wiry-rapid pulse. It is worth noting that LYHS is usually caused by LKYDS. And these syndromes often appear together in EH. Molecular mechanism of LYHS and LKYDS in EH may be related to the hyperexpression of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), and fifteen compounds of the structure and metabolic pathways mainly including amino acids, free fatty acids, and sphingosine by high performance liquid chromatography coupled with time of flight mass spectrometry (HPLC-TOFMS) [47–49]. Our previous studies showed that LYHS and LKYDS are the most important pathogenesis of EH in TCM, which could be well treated by Tianma Gouteng Yin (TGY) [46]. TGY, containing eleven commonly used herbs (Gastrodia elata, Uncaria, abalone shell, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv, achyranthes root, Loranthus parasiticus, Gardenia, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi, Leonurus japonicus, Poria cocos, and caulis polygoni multiflori), is a classical Chinese herbal formula noted in Za Bing Zheng Zhi Xin Yi (New Meanings in Syndrome and Therapy of Miscellaneous Diseases). It has been widely used to treat hypertension-related symptoms and signs in clinical practice for decades [46]. The most common symptoms include headache, dizziness, insomnia, and lassitude in lion and legs, red tongue with scanty coating, and wiry-rapid pulse, which belong to LYHS and LKYDS in TCM [46]. The mechanism of the formula may be suppressing liver yang hyperactivity and nourishing the liver and kidney. Recently, modern researches showed that TGY could not only improve hypertension-related symptoms and signs, but also lower BP in vitro and in vivo [50–60]. Biochemically, TGY appears to have good effect in inhibiting vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis by decreasing TGF-β1 and Bcl-2, improving vascular remodeling, inhibiting left ventricular hypertrophy and myocardial fibrosis, regulating rennin-angiotensin system (RAS) and Ca2+ overload in vascular smooth muscle cells, improving SOD, nitric oxide and insulin resistance, and decreasing endothelin, MDA, and IGF-1, so as to lower the arterial pressure [50–60].

Currently, a number of clinical trials have been published in Chinese language by TGY used alone or combined with antihypertensive drugs for EH. However, there is no critically appraised evidence such as SRs or meta-analyses to assess clinical efficacy and safety of TGY combined with antihypertensive drugs as an adjunct therapy for hypertensive patients based on TCM zheng classification. The PAPER aims to evaluate the beneficial and harmful effects of TGY for EH in randomized trials. To our knowledge, this is the first zheng classification-based systematic English review on TGY for EH.

2. Methods

2.1. Database and Search Strategies

Literature searches were conducted in the Cochrane Library (July, 2012), PubMed, EMBASE, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Scientific Journal Database (VIP), Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM), and Wanfang data. The reference list of retrieved papers was also searched. Since TGY was mainly used and researched in China, four main databases in Chinese were searched to retrieve the maximum possible number of trials of TGY combined with antihypertensive drugs for EH. All of those searches ended on November 20, 2012. Ongoing registered clinical trials were searched in the website of Chinese clinical trial registry (http://www.chictr.org/en/) and international clinical trial registry by US national institutes of health (http://clinicaltrials.gov/). The following search terms were used individually or combined: “Tianma Gouteng yin,” “Tianma Gouteng decoction,” “Tianma Gouteng tang,” “hypertension,” “essential hypertension,” “clinical trial,” and “randomized controlled trial.” The bibliographies of included studies were searched for additional references.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

All the parallel randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of all the prescriptions based on “Tianma Gouteng yin” combined with antihypertensive drugs compared to antihypertensive drugs for EH with LYHS and LKYDS were included. According to the principle of the similarity of TCM formula [42, 61], the number of modified herbs should not be more than 5, so that to ensure the similarity is greater than or equal to 0.5. And the key herbs in the modified Tianma Gouteng yin should include Gastrodia elata, Uncaria, and abalone shell, according to the theory of TCM. There were no restrictions on population characteristics, language and publication type. Duplicated publications reporting the same groups of participants were excluded.

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two authors conducted the literature searching (X. J. Xiong, W. Liu), study selection (X. J. Xiong, B. Feng), and data extraction (X. J. Xiong, X. C. Yang) independently. The extracted data included authors, title of study, year of publication, study size, age and sex of the participants, details of methodological information, name and component of Chinese herbs, treatment process, details of the control interventions, outcomes, and adverse effects for each study. Disagreement was resolved by discussion and reached consensus through a third party (J. Wang).

Criteria from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions, Version 5.1.0 were used to assess the methodological quality of trials (X. J. Xiong, Y. Zhang) [62]. The items included random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective reporting (reporting bias), and other bias. The quality of all the included trials was categorized to low/unclear/high risk of bias (“Yes” for a low of bias, “No” for a high risk of bias, “Unclear” otherwise). Then trials were categorized into three levels: low risk of bias (all the items were in low risk of bias), high risk of bias (at least one item was in high risk of bias), unclear risk of bias (at least one item was in unclear risk of bias).

2.4. Data Synthesis

Revman 5.1 software provided by the Cochrane Collaboration was used for data analyses. Dichotomous data were presented as risk ratio (RR) and continuous outcomes as mean difference (MD), both with 95% confidence interval (CI). Heterogeneity was recognized significant when I 2 ≥ 50%. Fixed effects model was used if there is no significant heterogeneity of the data; random effects model was used if significant heterogeneity existed (50% < I 2 < 85%). Publication bias would be explored by funnel plot analysis if sufficient studies were found.

3. Result

3.1. Description of Included Trials

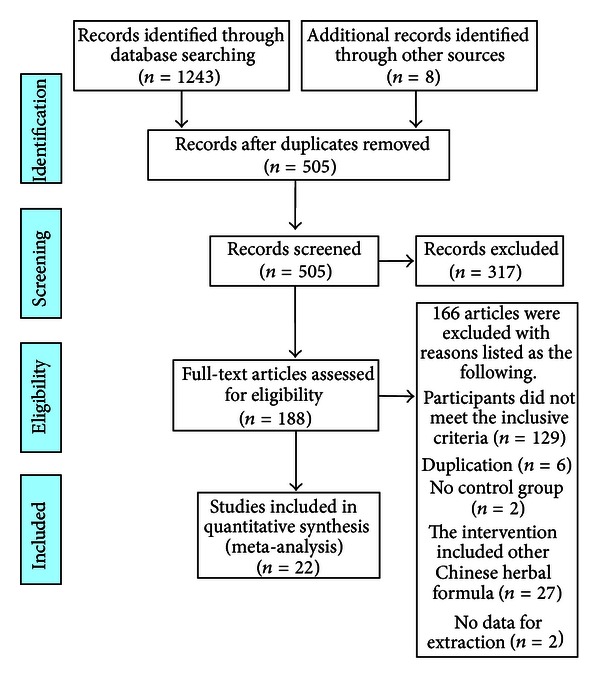

A flow chart depicted the search process and study selection (as shown in Figure 1). After primary searches from the seven databases both in Chinese and English, 1243 articles were retrieved: Cochrane Library (n = 1), Pubmed (n = 6), EMBASE (n = 19), CNKI (n = 499), VIP (n = 247), CBM (n = 270), and Wanfang data (n = 201). 505 articles were screened after 746 duplicates were removed. After reading the titles and abstracts, 317 articles of them were excluded. Full texts of 188 articles were retrieved, and 166 articles were excluded with reasons listed as the following: participants did not meet the inclusive criteria (n = 129), duplication (n = 6), no control group (n = 2), the intervention included other Chinese herbal formula (n = 27), and no data for extraction (n = 2). In the end, 22 RCTs [63–84] were included. All the RCTs were conducted in China and published in Chinese. The characteristics of included trials were listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics and methodological quality of included studies.

| Study ID | Sample | Diagnosis standard | Intervention | Control | Course (week) | Outcome measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al., 1998 [63] | 98 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH; TCM diagnostic criteria (unclear) | modified TGY (1 dose/d) + control | captopril (25 mg tid) | 4 | BP; TCM zheng |

| Ren and Zhao, 2012 [64] | 60 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH; GCRNDTCM | modified TGY (300 mL/d) + control | nifedipine sustained release tablets (10 mg bid) | 6 | BP |

| Fu, 2005 [65] | 116 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH; TCM diagnostic criteria (unclear) | modified TGY (250 mL/d) + control | enalapril (10 mg bid) | 2 | BP |

| Qin, 2010 [66] | 45 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH; GCRNDTCM | TGY (1 dose/d) + control | antihypertensive drugs (no detailed information) | 4 | BP |

| Hu et al., 2009 [67] | 39 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH; GCRNDTCM | TGY (1 dose/d) + captopril | captopril (12.5–25 mg bid) + TGY placebo | 4 | BP |

| Sun and Huang, 2007 [68] | 60 | hypertension diagnostic criteria (unclear); GCRNDTCM | TGY (1 dose/d) + control | hydrochlorothiazide (12.5 mg bid) | 4 | BP |

| Wang et al., 2008 [69] | 80 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH; GCRNDTCM | TGY (1 dose/d) + control | captopril (25 mg tid) | 4 | BP; TCM zheng |

| Fang et al., 2008 [70] | 60 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH; GCRNDTCM | TGY (1 dose/d) + control | captopril (25 mg tid) | 4 | BP |

| Li, 2006 [71] | 80 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH; CIM | modified TGY (1 dose/d) + control | captopril (12.5 mg bid) | 4 | BP; TCM zheng |

| Liu, 2011 [72] | 86 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH; GCRNDTCM | modified TGY (1 dose/d) + control | amlodipine besylate (5 mg qd) | 8 | BP; TCM zheng |

| Liu et al., 2009 [73] | 60 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH; GCRNDTCM | TGY (1 dose/d) + control | perindopril (25 mg tid) | 4 | BP; TCM zheng |

| Chen, 2009 [74] | 100 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH; GCRNDTCM | TGY (1 dose/d) + control | captopril (25 mg tid) | 6 | BP; TCM zheng |

| Zhang and Yang, 2011 [75] | 60 | CGMH-2005; GCRNDTCM | modified TGY (1 dose/d) + control | amlodipine besylate (5 mg qd) + lisinopril (10 mg qd) | 4 | BP; TCM zheng |

| Liu and Li, 2011 [76] | 100 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH; CIM | TGY (1 dose/d) + control | nifedipine sustained release tablets (10 mg bid) | 4 | BP |

| Wei, 2012 [77] | 98 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH; TCM diagnostic criteria (unclear) | TGY (1 dose/d) + control | nifedipine (10 mg bid) | 4 | BP |

| Li, 2011 [78] | 120 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH; GCRNDTCM | TGY (1 dose/d) + control | levamlodipine (5 mg qd) | 4 | BP |

| Lin and Liu, 2010 [79] | 94 | CGMH-2005; GCRNDTCM | TGY (1 dose/d) + control | telmisartan (20 mg qd) | 4 | BP |

| Zhou and Zhang, 2011 [80] | 72 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH; GCRNDTCM | modified TGY (1 dose/d) + control | captopril (25 mg bid) | 4 | BP |

| Chen, 2008 [81] | 100 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH; GCRNDTCM | TGY (1 dose/d) + control | captopril (25 mg tid) | 6 | BP; TCM zheng |

| Du, 2012 [82] | 100 | CGMH-1999; GCRNDTCM | modified TGY (1 dose/d) + control | captopril (25 mg tid) | 4 | BP |

| Cheng, 2010 [83] | 100 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH; GCRNDTCM | modified TGY (1 dose/d) + control | enalapril (10 mg qd) | 12 | BP |

| Zhu, 2009 [84] | 80 | 1999 WHO-ISH GMH; GCRNDTCM | TGY (1 dose/d) + control | captopril (25 mg tid) | 4 | BP |

1808 patients with EH were included. There was a wide variation in the age of subjects (30–74 years). Twenty-two included clinical trials specified four diagnostic criteria of hypertension, eighteen trials [63–67, 69–74, 76–78, 80, 81, 83, 84] used 1999 WHO-ISH guidelines for the management of hypertension (1999 WHO-ISH GMH), two trials [75, 79] used Chinese Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension-2005 (CGMH-2005), one trial [82] used Chinese Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension-1999 (CGMH-1999), and one trial [68] only demonstrated patients with EH without detailed information. Twenty-two (22) trials specified three diagnostic criteria of LYHS and LKYDS in TCM, seventeen trials [64, 66–70, 72–75, 78–84] used Guidelines of Clinical Research of New Drugs of Traditional Chinese Medicine (GCRNDTCM), two trials [71, 76] used Chinese internal medicine (CIM), and three trials [63, 65, 77] only demonstrated patients with LYHS and LKYDS without detailed information about TCM diagnostic criteria.

Interventions included all the prescriptions based on “Tianma Gouteng yin” combined with antihypertensive drugs. The controls included antihypertensive drugs alone. The total treatment duration ranged from 2 to 12 weeks. The variable prescriptions are presented in Table 1. The compositions of Chinese herbal formula Tianma Gouteng yin are presented in Table 2. All of the 22 trials used the BP, including systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP), as the outcome measure. 9 trials [63, 69, 71–75, 78, 81] used TCM zheng to evaluate treatment effects as the other outcome measure.

Table 2.

Composition of formula.

| Study ID | Formula | Composition of formula |

|---|---|---|

| Wang et al., 1998 [63] | modified TGY | Salvia miltiorrhiza 30 g, red peony root 20 g, Gastrodia elata 12 g, Uncaria 30 g, abalone shell 30 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 15 g, achyranthes root 30 g, Loranthus parasiticus 15 g, Gardenia 12 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 12 g, Leonurus japonicus 20 g, Poria cocos 15 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 30 g |

|

| ||

| Ren and Zhao, 2012 [64] | modified TGY | Gastrodia elata 9 g, Uncaria 12 g, abalone shell 18 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 9 g, achyranthes root 12 g, Loranthus parasiticus9 g, Gardenia 9 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 9 g, Leonurus japonicus 9 g, scu9 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 9 g |

|

| ||

| Fu, 2005 [65] | modified TGY | Gastrodia elata 18 g, Uncaria 12 g, abalone shell 18 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 9 g, achyranthes root 15 g, Loranthus parasiticus 9 g, Gardenia 9 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 12 g, Leonurus japonicus 9 g, Poria cocos 9 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 9 g, Prunella vulgaris 12 g |

|

| ||

| Qin, 2010 [66] | TGY | Gastrodia elata, Uncaria, abalone shell, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv, achyranthes root, Loranthus parasiticus, Gardenia, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi, Leonurus japonicus, Poria cocos, caulis polygoni multiflori |

|

| ||

| Hu et al., 2009 [67] | TGY | Gastrodia elata 9 g, Uncaria 12 g, abalone shell 18 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 9 g, achyranthes root 12 g, Loranthus parasiticus 9 g, Gardenia 9 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 9 g, Leonurus japonicus 9 g, Poria cocos 9 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 9 g |

|

| ||

| Sun and Huang, 2007 [68] | TGY | Gastrodia elata 9 g, Uncaria 12 g, abalone shell 18 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 9 g, achyranthes root 12 g, Loranthus parasiticus 9 g, Gardenia 9 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 9 g, Leonurus japonicus 9 g, Poria cocos 9 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 9 g |

|

| ||

| Wang et al., 2008 [69] | TGY | Gastrodia elata 15 g, Uncaria 30 g, abalone shell 21 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 12 g, achyranthes root 15 g, Loranthus parasiticus 12 g, Gardenia 12 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 12 g, Leonurus japonicus 12 g, Poria cocos 12 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 12 g |

|

| ||

| Fang et al., 2008 [70] | TGY | Gastrodia elata 9 g, Uncaria 12 g, abalone shell 18 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 9 g, achyranthes root 12 g, Loranthus parasiticus 9 g, Gardenia 9 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 9 g, Leonurus japonicus 9 g, Poria cocos 9 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 9 g |

|

| ||

| Li, 2006 [71] | modified TGY | Gastrodia elata 10 g, Uncaria 12 g, abalone shell 30 g, achyranthes root 15 g, Loranthus parasiticus 15 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 10 g, Leonurus japonicus 20 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 25 g, white peony root 15 g, Chrysanthemum 12 g |

|

| ||

| Liu, 2011 [72] | modified TGY | Gastrodia elata 10 g, Uncaria 15 g, abalone shell 20 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 10 g, achyranthes root 15 g, Loranthus parasiticus 15 g, Gardenia 10 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 10 g, Poria cocos 30 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 15 g, Apocynum 10 g |

|

| ||

| Liu et al., 2009 [73] | TGY | Gastrodia elata 9 g, Uncaria 12 g, abalone shell 18 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 9 g, achyranthes root 12 g, Loranthus parasiticus 9 g, Gardenia 9 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 9 g, Leonurus japonicus 9 g, Poria cocos 9 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 9 g |

|

| ||

| Chen, 2009 [74] | TGY | Gastrodia elata 12 g, Uncaria 9 g, abalone shell 30 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 12 g, achyranthes root 15 g, Loranthus parasiticus 15 g, Gardenia 9 g, Leonurus japonicus 15 g, Poria cocos 15 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 20 g |

|

| ||

| Zhang and Yang, 2011 [75] | modified TGY | Gastrodia elata 10 g, Uncaria 30 g, abalone shell 30 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 10 g, achyranthes root 15 g, Loranthus parasiticus 15 g, Poria cocos 15 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 15 g, Salvia miltiorrhiza 30 g, Prunella vulgaris 15 g, keel 30 g, oyster 30 g, pearl shell 30 g, Albizia julibrissin 15 g, Glycyrrhiza 6 g |

|

| ||

| Liu and Li, 2011 [76] | TGY | Gastrodia elata 15 g, Uncaria 30 g, abalone shell 30 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 15 g, achyranthes root 15 g, Loranthus parasiticus 30 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 15 g, Leonurus japonicus 15 g, Poria cocos 20 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 15 g |

|

| ||

| Wei, 2012 [77] | TGY | Gastrodia elata 10 g, Uncaria 15 g, abalone shell 20 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 10 g, achyranthes root 15 g, Loranthus parasiticus 15 g, Gardenia 10 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 10 g, Leonurus japonicus 15 g, Poria cocos 15 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 10 g |

|

| ||

| Li, 2011 [78] | TGY | Gastrodia elata 10 g, Uncaria 15 g, abalone shell 20 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 10 g, achyranthes root 15 g, Loranthus parasiticus 15 g, Gardenia 10 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 10 g, Leonurus japonicus 15 g, Poria cocos 15 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 10 g |

|

| ||

| Lin and Liu, 2010 [79] | TGY | Gastrodia elata 9 g, Uncaria 12 g, abalone shell 30 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 10 g, achyranthes root 12 g, Loranthus parasiticus 12 g, Gardenia 6 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 9 g, Leonurus japonicus 9 g, Poria cocos 12 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 12 g |

|

| ||

| Zhou and Zhang, 2011 [80] | modified TGY | Gastrodia elata 12 g, Uncaria 10 g, abalone shell 10 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 10 g, achyranthes root 10 g, Loranthus parasiticus 10 g, Gardenia 9 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 9 g, Leonurus japonicus 15 g, Poria cocos 10 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 10 g, Gentiana scabra bge 15 g |

|

| ||

| Chen, 2008 [81] | TGY | Gastrodia elata 12 g, Uncaria 9 g, abalone shell 30 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 12 g, achyranthes root 15 g, Loranthus parasiticus 15 g, Gardenia 9 g, Leonurus japonicus 15 g, Poria cocos 15 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 20 g |

|

| ||

| Du, 2012 [82] | modified TGY | Gastrodia elata 15 g, Uncaria 20 g, abalone shell 15 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 10 g, achyranthes root 10 g, Loranthus parasiticus 10 g, Gardenia 6 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 8 g, Leonurus japonicus 10 g, Poria cocos 10 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 30 g; constipation plus rhubarb 5 g and aloe vera 10 g; liver-kidney yin deficiency plus glossy privet 10 g, wolfberry fruit 15 g, Rehmanniae radix 15 g, root of herbaceous peony 10 g; gan yang hua feng syndrome and dizziness plus antelope horn 3 g, pearl shell 15 g, keel 30 g and oyster 30 g; severe headache, flushed face and congested eyes and coating on the tongue yellow dry plus Gentiana scabra bge 15 g, Chrysanthemum 10 g, cortex moutan radicis 10 g |

|

| ||

| Cheng, 2010 [83] | modified TGY | Gastrodia elata 12 g, Uncaria 12 g, abalone shell 18 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 12 g, achyranthes root 12 g, Loranthus parasiticus 12 g, Gardenia 12 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 12 g, Leonurus japonicus 12 g, Poria cocos 12 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 9 g, hawthorn 30 g, giant knotweed 10 g |

|

| ||

| Zhu, 2009 [84] | TGY | Gastrodia elata 9 g, Uncaria 12 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv 9 g, achyranthes root 12 g, Loranthus parasiticus 9 g, Gardenia 9 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 9 g, Leonurus japonicus 9 g, Poria cocos 9 g, caulis polygoni multiflori 9 g |

3.2. Methodological Quality of Included Trials

The majority of the included clinical trials were assessed to be of general poor methodological quality according to the predefined quality assessment criteria. The randomized allocation of participants was mentioned in all trials; however, only seven trials have described the specific methods for sequence generation including random number table [64, 75, 80, 84] and drawing [74, 81]. One trial [67] only reported simple random sampling without concrete information. The remaining fifteen studies [63, 65, 66, 68–73, 76–79, 82, 83] did not mention the random sequence generation. There is also no sufficient information provided to judge whether it was conducted properly or not. Allocation concealment was not reported in all the trials. Only one trial [67] used the blinding of participants and personnel; however, no trial reported blinding of outcome assessment. Three trials [67–69] reported drop-out or withdraw. A pretrial estimation of sample size and followup had not been reported in all of included trials. We have tried to contact with authors by telephone, email, and other ways for further information about the trials; however, no information could be provided until now. The results of the assessment of risk of bias are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Quality assessment of included randomized controlled trials.

| Included trials | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Other sources of bias | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al., 1998 [63] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Ren and Zhao, 2012 [64] | Table of random number | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | Unclear |

| Fu, 2005 [65] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Qin, 2010 [66] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Hu et al., 2009 [67] | Simple random sampling | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | No | No | Unclear | Unclear |

| Sun and Huang, 2007 [68] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | Unclear | High |

| Wang et al., 2008 [69] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Fang et al., 2008 [70] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | Unclear | High |

| Li, 2006 [71] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Liu, 2011 [72] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Liu et al., 2009[73] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Chen, 2009 [74] | Drawing | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | Unclear | Unclear |

| Zhang and Yang, 2011 [75] | Table of random number | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | Unclear |

| Liu and Li, 2011 [76] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | Unclear | High |

| Wei, 2012 [77] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Li, 2011 [78] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Lin and Liu, 2010 [79] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Zhou and Zhang, 2011 [80] | Table of random number | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | Unclear | Unclear |

| Chen, 2008 [81] | Drawing | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | Unclear | Unclear |

| Du, 2012 [82] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Cheng, 2010 [83] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | High |

| Zhu, 2009 [84] | Table of random number | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | Unclear | Unclear |

3.3. Effect of the Interventions

All the included trials [63–84] compared TGY combined with antihypertensive drugs with antihypertensive drugs alone. A change in BP was reported in all the trials. According to the different control drugs, it could be divided into six subgroups.

3.3.1. TGY Plus ACEI versus ACEI

13 trials compared TGY plus angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) versus ACEI (including captopril, enalapril, and perindopril) [63, 65, 67, 69–71, 73, 74, 80–84].

Blood Pressure (BP). 8 trial [65, 71, 73, 74, 80–83] used three classes to evaluate treatment effects on BP: significant effective (DBP decreased by 10 mmHg reaching the normal range, or DBP has not yet returned to normal, but has been reduced ≥20 mmHg), effective (DBP decreased to less than 10 mmHg reaching the normal range, or DBP decreased by 10–19 mmHg, but did not reach the normal range, or, SBP decreased ≥30 mmHg), and ineffective (Not to meet the above standards). The trial showed significant difference between treatment and control group (RR: 3.16 [1.94, 5.14]; P < 0.00001) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Analyses of blood pressure.

| Trials | Intervention (n/N) | Control (n/N) | RR [95% CI] | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGY plus ACEI versus ACEI | |||||

| modified TGY plus enalapril versus enalapril | 1 | 56/60 | 44/56 | 3.82 [1.15, 12.66] | 0.03 |

| modified TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | 44/48 | 21/32 | 5.76 [1.64, 20.25] | 0.006 |

| TGY plus perindopril versus perindopril | 1 | 29/30 | 26/30 | 4.46 [0.47, 42.51] | 0.19 |

| TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | 45/50 | 44/50 | 1.23 [0.35, 4.32] | 0.75 |

| modified TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | 34/36 | 30/36 | 3.40 [0.64, 18.13] | 0.15 |

| TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | 45/50 | 44/50 | 1.23 [0.35, 4.32] | 0.75 |

| modified TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | 48/50 | 42/50 | 4.57 [0.92, 22.73] | 0.06 |

| modified TGY plus enalapril versus enalapril | 1 | 48/50 | 39/50 | 6.77 [1.42, 32.37] | 0.02 |

|

| |||||

| Meta-Analysis | 8 | 349/374 | 290/354 | 3.16 [1.94, 5.14] | <0.00001 |

|

| |||||

| TGY plus CCB versus CCB | |||||

| TGY plus nifedipine versus nifedipine | 1 | 48/49 | 40/49 | 10.80 [1.31, 88.92] | 0.03 |

| TGY plus levamlodipine versus levamlodipine | 1 | 58/60 | 47/60 | 8.02 [1.72, 37.33] | 0.008 |

|

| |||||

| Meta-Analysis | 2 | 106/109 | 87/109 | 8.97 [2.59, 31.04] | 0.0005 |

|

| |||||

| TGY plus antihypertensive drugs versus antihypertensive drugs | |||||

| TGY plus antihypertensive drugs versus antihypertensive drugs | 1 | 20/22 | 17/23 | 3.53 [0.63, 19.83] | 0.01 |

|

| |||||

| Meta-Analysis | 1 | 20/22 | 17/23 | 3.53 [0.63, 19.83] | 0.01 |

When it comes to SBP, 5 independent trials [63, 67, 69, 70, 84] showed significant heterogeneity in the results, chi-square = 20.01, (P = 0.0005); I 2 = 80%. Thus, random-effects model was used for statistical analysis. The meta-analysis showed that there are significant beneficial effect on the combination group compare to captopril group (WMD: −6.71 [−6.94, −6.49]; P < 0.00001) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Analyses of systolic blood pressure.

| Trials | MD [95% CI] | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TGY plus ACEI versus ACEI | |||

| modified TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | −9.70 [−11.80, −7.60] | <0.00001 |

| TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | −6.20 [−7.03, −5.37] | <0.00001 |

| TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | −8.76 [−10.02, −7.50] | <0.00001 |

| TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | −5.30 [−9.88, −0.72] | 0.02 |

| TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | −6.65 [−6.89, −6.41] | <0.00001 |

|

| |||

| Meta-Analysis | 5 | −6.71 [−6.94, −6.49] | <0.00001 |

|

| |||

| TGY plus CCB versus CCB | |||

| modified TGY plus nifedipine sustained release tablets versus nifedipine sustained release tablets | 1 | −13.00 [−14.48, −11.52] | <0.00001 |

| modified TGY plus amlodipine besylate versus amlodipine besylate | 1 | −12.60 [−13.69, −11.51] | <0.00001 |

| TGY plus nifedipine sustained release tablets versus nifedipine sustained release tablets | 1 | −10.68 [−11.62, −9.74] | <0.00001 |

|

| |||

| Meta-Analysis | 3 | −12.25 [−13.52, −10.54] | <0.00001 |

|

| |||

| TGY plus diuretics versus diuretics | |||

| modified TGY plus hydrochlorothiazide versus hydrochlorothiazide | 1 | 0.28 [−0.72, 1.28] | 0.58 |

|

| |||

| Meta-Analysis | 1 | 0.28 [−0.72, 1.28] | 0.58 |

|

| |||

| TGY plus ARB versus ARB | |||

| TGY plus telmisartan versus telmisartan | 1 | −3.70 [−3.78, −3.62] | <0.00001 |

|

| |||

| Meta-Analysis | 1 | −3.70 [−3.78, −3.62] | <0.00001 |

|

| |||

| TGY plus “CCB + ACEI” versus “CCB + ACEI” | |||

| modified TGY plus amlodipine besylate and lisinopril versus amlodipine besylate and lisinopril | 1 | −11.03 [−12.72, −9.34] | <0.00001 |

|

| |||

| Meta-Analysis | 1 | −11.03 [−12.72, −9.34] | <0.00001 |

When it comes to DBP, 5 independent trials [63, 67, 69, 70, 84] showed significant heterogeneity in the results, chi-square = 14.66, (P = 0.005); I 2 = 73%. Thus, random-effects model was used for statistical analysis. The meta-analysis showed there are significant beneficial effects on the combination group compared to captopril group (WMD: −4.60 [−5.11, −4.09]; P < 0.00001) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Analyses of diastolic blood pressure.

| Trials | MD [95% CI] | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TGY plus ACEI versus ACEI | |||

| modified TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | −6.10 [−9.06, −3.14] | <0.0001 |

| TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | −5.00 [−5.89, −4.11] | <0.00001 |

| TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | −3.69 [−4.44, −2.94] | <0.00001 |

| TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | −3.30 [−7.12, 0.52] | 0.09 |

| TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | −6.28 [−7.55, −5.01] | <0.00001 |

|

| |||

| Meta-Analysis | 5 | −4.60 [−5.11, −4.09] | <0.00001 |

|

| |||

| TGY plus CCB versus CCB | |||

| modified TGY plus nifedipine sustained release tablets versus nifedipine sustained release tablets | 1 | −10.00 [−12.53, −7.47] | <0.00001 |

| modified TGY plus amlodipine besylate versus amlodipine besylate | 1 | −8.20 [−8.58, −7.82] | <0.00001 |

| TGY plus nifedipine sustained release tablets versus nifedipine sustained release tablets | 1 | −7.34 [−7.73, −6.95] | <0.00001 |

|

| |||

| Meta-Analysis | 3 | −7.98 [−8.85, −7.12] | <0.00001 |

|

| |||

| TGY plus diuretics versus diuretics | |||

| modified TGY plus hydrochlorothiazide versus hydrochlorothiazide | 1 | 0.44 [−0.52, 1.40] | 0.37 |

|

| |||

| Meta-Analysis | 1 | 0.44 [−0.52, 1.40] | 0.37 |

|

| |||

| TGY plus ARB versus ARB | |||

| TGY plus telmisartan versus telmisartan | 1 | −0.80 [−1.57, −0.03] | 0.04 |

|

| |||

| Meta-Analysis | 1 | −0.80 [−1.57, −0.03] | 0.04 |

|

| |||

| TGY plus “CCB + ACEI” versus “CCB + ACEI” | |||

| modified TGY plus amlodipine besylate and lisinopril versus amlodipine besylate and lisinopril | 1 | −6.87 [−7.60, −6.14] | <0.00001 |

|

| |||

| Meta-Analysis | 1 | −6.87 [−7.60, −6.14] | <0.00001 |

TCM Zheng. 6 trials [63, 69, 71, 73, 74, 81] used three classes to measure TCM zheng (just LYHS and LKYDS): significant effective (The main symptoms such as headache, dizziness, palpitations, insomnia, tinnitus, and irritability disappear, or TCM zheng scores reduced rate ≥70%), effective (The main symptoms relieved, or, 70% > TCM zheng scores reduced rate ≥30%), and ineffective (The main symptoms do not change, or TCM zheng scores reduced rate <30%). Meta-analysis showed significant difference in favor of the combination group compared to ACEI group (RR: 6.15 [3.38, 11.18]; P < 0.00001) (Table 7).

Table 7.

Analyses of TCM zheng.

| Trials | Intervention (n/N) | Control (n/N) | RR [95% CI] | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGY plus ACEI versus ACEI | |||||

| modified TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | 48/50 | 36/48 | 8.00 [1.68, 38.00] | 0.009 |

| TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | 38/40 | 28/40 | 8.14 [1.69, 39.22] | 0.009 |

| modified TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | 44/48 | 21/32 | 5.76 [1.64, 20.25] | 0.006 |

| TGY plus perindopril versus perindopril | 1 | 29/30 | 23/30 | 8.83 [1.01, 76.96] | 0.05 |

| TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | 47/50 | 38/50 | 4.95 [1.30, 18.81] | 0.02 |

| TGY plus captopril versus captopril | 1 | 47/50 | 39/50 | 4.42 [1.15, 16.97] | 0.03 |

|

| |||||

| Meta-Analysis | 6 | 253/268 | 185/250 | 6.15 [3.38, 11.18] | <0.00001 |

|

| |||||

| TGY plus CCB versus CCB | |||||

| modified TGY plus amlodipine besylate versus amlodipine besylate | 1 | 42/46 | 26/40 | 5.65 [1.68, 19.04] | 0.005 |

| TGY plus levamlodipine versus levamlodipine | 1 | 55/60 | 40/60 | 5.50 [1.90, 15.89] | 0.002 |

|

| |||||

| Meta-Analysis | 2 | 97/106 | 66/100 | 5.56 [2.50, 12.37] | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| TGY plus “CCB + ACEI” versus “CCB + ACEI” | |||||

| modified TGY plus amlodipine besylate and lisinopril versus amlodipine besylate and lisinopril | 1 | 29/30 | 22/30 | 10.55 [1.23, 90.66] | 0.03 |

|

| |||||

| Meta-Analysis | 1 | 29/30 | 22/30 | 10.55 [1.23, 90.66] | 0.03 |

3.3.2. TGY Plus CCB versus CCB

5 trials compared TGY plus calcium channel blockers (CCB) versus CCB (including nifedipine sustained release tablets, amlodipine besylate, nifedipine, and levamlodipine) [64, 72, 76–78].

Blood Pressure (BP). 2 trials [77, 78] used three classes to evaluate treatment effects on BP. The trials showed significant difference between treatment and control group (RR: 8.97 [2.59, 31.04]; P = 0.0005) (Table 4).

When it comes to SBP, 3 independent trials [64, 72, 76] showed significant heterogeneity in the results, chi-square = 10.10, (P = 0.006); I 2 = 80%. Thus, random-effects model was used for statistical analysis. The meta-analysis showed there are significant beneficial effects on the combination group compared to captopril group (WMD: −12.03 [−13.52, −10.54]; P < 0.00001) (Table 5).

When it comes to DBP, 3 independent trials [64, 72, 76] showed significant heterogeneity in the results, chi-square = 12.39, (P = 0.002); I 2 = 84%. Thus, random-effects model was used for statistical analysis. The meta-analysis showed there are significant beneficial effects on the combination group compared to captopril group (WMD: −7.98 [−8.85, −7.12]; P < 0.00001) (Table 6).

TCM Zheng. 2 trials [72, 78] used three classes to evaluate treatment effects on TCM zheng. The trials showed significant difference between treatment and control group (RR: 5.56 [2.50, 12.37]; P < 0.0001) (Table 7).

3.3.3. TGY Plus Diuretics versus Diuretics

1 trial compared TGY plus diuretics versus diuretics (including hydrochlorothiazide) [68]. When it comes to SBP, it [68] showed no applicable heterogeneity in the result. Thus, fixed-effects model was used for statistical analysis. The meta-analysis showed there is no significant beneficial effect on the combination group compared to hydrochlorothiazide group (WMD: 0.28 [−0.72, 1.28]; P = 0.58) (Table 5).

When it comes to DBP, it [68] showed no applicable heterogeneity in the result. Thus, fixed-effects model was used for statistical analysis. The meta-analysis showed there is no significant beneficial effect on the combination group compared to hydrochlorothiazide group (WMD: 0.44 [−0.52, 1.40]; P = 0.37) (Table 6).

3.3.4. TGY Plus ARB versus ARB

1 trial compared TGY plus angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) versus ARB (including telmisartan) [79]. When it comes to SBP, it showed no applicable heterogeneity in the result. Thus, fixed-effects model was used for statistical analysis. The meta-analysis showed there is significant beneficial effect on the combination group compared to telmisartan group (WMD: −3.70 [−3.78, −3.62]; P < 0.00001) (Table 5).

When it comes to DBP, it showed no applicable heterogeneity in the result. Thus, fixed-effects model was used for statistical analysis. The meta-analysis showed there is significant beneficial effect on the combination group compared to telmisartan group (WMD: −0.80 [−1.57, −0.03]; P = 0.04) (Table 6).

3.3.5. TGY Plus “CCB + ACEI” versus “CCB + ACEI”

1 trial [75] compared TGY plus “CCB + ACEI” versus “CCB + ACEI” (including amlodipine besylate and lisinopril).

Blood Pressure (BP). When it comes to SBP, it showed no applicable heterogeneity in the result. Thus, fixed-effects model was used for statistical analysis. Meta-analysis showed there is significant beneficial effect on the combination group compared to “amlodipine besylate and lisinopril” group (WMD: −11.03 [−12.72, −9.34]; P < 0.00001) (Table 5).

When it comes to DBP, it showed no applicable heterogeneity in the result. Thus, fixed-effects model was used for statistical analysis. Meta-analysis showed there is significant beneficial effect on the combination group compared to “amlodipine besylate and lisinopril” group (WMD: −6.87 [−7.60, −6.14]; P < 0.00001) (Table 6).

TCM Zheng. 1 trial [75] used three classes to evaluate treatment effects on TCM zheng. It showed significant difference between treatment and control group (RR: 10.55 [1.23, 90.66]; P = 0.03) (Table 7).

3.3.6. TGY Plus Antihypertensive Drugs versus Antihypertensive Drugs

1 trial [66] compared TGY plus antihypertensive drugs versus antihypertensive drugs with no detailed information. It used three classes to evaluate treatment effects on BP. The trial showed significant difference between combination group and antihypertensive drugs group (RR: 3.53 [0.63, 19.83]; P = 0.01) (Table 4).

3.4. Publication Bias

The number of trials was too small to conduct any sufficient additional analysis of publication bias.

3.5. Adverse Effect

Eight out of twenty-two trials mentioned the adverse effect [67, 68, 70, 74, 76, 80, 81, 84]. Eight trials reported five specific symptoms including cough, vomiting, flushing, rash, and edema. Among them, no adverse events were found in one trial [80]. Two trials reported cough and vomiting in combination group and antihypertensive drugs group, respectively [67, 68]. Three trials reported cough in both TGY plus captopril group and captopril group [70, 74, 81]. One trial mentioned flushing in both TGY plus nifedipine sustained release tablets group and nifedipine sustained release tablets group [76]. One trial mentioned cough, rash, and edema in TGY plus captopril group, and cough and rash in captopril group [84].

4. Discussion

Due to the potential side effects of antihypertensive drugs, natural herbal products have been favored by people all over the world. Chinese herbal formula has made great contributions to the health and well-being of the people for their unique advantages in preventing and curing diseases, rehabilitation and health care. Currently, with increasing popularity of TCM [85, 86], more and more systematic reviews (SRs) and meta-analysis have been conducted to assess the efficiency of TCM for EH [87–93]. It is demonstrated that Chinese herbal medicine could not only contribute to low BP smoothly, recover the circadian rhythm of BP, but also improve symptoms and TCM zheng especially [94]. The health-enhancing qualities of TGY, a classical Chinese formula, have been dispensed and used in China for many years. As an adjunctive treatment to antihypertensive drugs, TGY is a popular classical TCM formula for EH. And until now, more and more researches about TGY have been conducted in China including 2 SRs [95, 96]. Among them, one is published in English in Cochrane library [95], and the other is in Chinese [96]. However, due to different search strategies and databases both in English and Chinese, no trial was got in this Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and thus no conclusions can be made about the role of TGY in the treatment of EH [95]. Another one compared TGY plus enalapril with enalapril with positive conclusion [96]. However, as a famous adjunctive treatment in EH, the role of TGY is still unclear. This study aims to assess the current clinical evidence of TGY for EH with LYHS and LKYDS based on TCM zheng classification.

This systematic review included 22 randomized trials and a total of 1808 participants. As compared to ACEI, positive results in SBP (WMD: −6.71 [−6.94, −6.49]; P < 0.00001), DBP (WMD: −4.60 [−5.11, −4.09]; P < 0.00001), BP (RR: 3.16 [1.94, 5.14]; P < 0.00001), and TCM zheng (RR: 6.15 [3.38, 11.18]; P < 0.00001) were found about TGY plus ACEI, indicating that SBP and DBP could be decreased by 6.71 mmHg and 4.60 mmHg, respectively, and TCM zheng (just LYHS and LKYDS) could be improved after the combination therapy. As compared to CCB, positive results in SBP (WMD: −12.25 [−13.52, −10.54]; P < 0.00001), DBP (WMD: −7.98 [−8.85, −7.12]; P < 0.00001), BP (RR: 8.97 [2.59, 31.04]; P = 0.0005), and TCM zheng (RR: 5.56 [2.50, 12.37]; P < 0.0001) were found about TGY plus CCB, indicating that SBP and DBP could be decreased by 12.25 mmHg and 7.98 mmHg, respectively, and TCM zheng could be improved after the combination therapy. As compared to diuretics, there is no difference between TGY plus diuretics and diuretics in SBP (WMD: 0.28 [−0.72, 1.28]; P = 0.58) and DBP (WMD: 0.44 [−0.52, 1.40]; P = 0.37), indicating that no more beneficial effect was found in the combination therapy. As compared to ARB, positive results in SBP (WMD: −3.70 [−3.78, −3.62]; P < 0.00001) and DBP (WMD: −0.80 [−1.57, −0.03]; P = 0.04) were found about TGY plus ARB, indicating that SBP and DBP could be decreased by 3.70 mmHg and 0.80 mmHg, respectively, after the combination therapy. As compared to “CCB + ACEI,” positive results in SBP (WMD: −11.03 [−12.72, −9.34]; P < 0.00001), DBP (WMD: −6.87 [−7.60, −6.14]; P < 0.00001), and TCM zheng (RR: 10.55 [1.23, 90.66]; P = 0.03) were found about TGY plus “CCB + ACEI,” indicating that SBP and DBP could be decreased by 11.03 mmHg and 6.87 mmHg, respectively, and TCM zheng could be improved after the combination therapy. As compared to antihypertensive drugs, positive results in BP (RR: 3.53 [0.63, 19.83]; P = 0.01) was found about TGY plus antihypertensive drugs, indicating that BP could be improved after the combination therapy. In conclusion, except diuretics treatment group, BP was improved in the other 5 subgroups; TCM zheng was improved in ACEI, CCB, and “CCB + ACEI” treatment groups. However, although the meta-analysis showed positive results, no confirmed conclusion about the effectiveness and safety of TGY as adjunctive treatment for EH could be made according to current evidence due to the small sample size, poor methodological qualities, and significant heterogeneity of included trials.

The following limitations of this review should be considered. Firstly, according to the predefined evaluation criteria, the quality of methodology is generally low in most of the included trials. There is insufficient reporting of generation methods of the allocation sequence and allocation concealment, which might lead to potential selection bias. Although it is claimed that patients were randomly assigned into two groups, we are still unable to judge if it is conducted really. Most of clinical trials have not implemented double blind in this review, and only one trial used blinding of participants and personnel, which might lead to potential performance bias and detection bias. Therefore, assessment of outcomes was prone to significant systemic errors. Only 1 trial out of the 22 included studies has placebo control. T. J. Kaptchuk once pointed out that, in alternative medicine, the main question regarding placebo has been whether a given therapy has more than a placebo effect [97]. It also regarded that only prospective trials directly comparing the placebo effects of unconventional and mainstream medicine can provide reliable evidence to support such claims [97, 98]. In this review, the result would be positive because of nonspecific placebo effects. In our opinion, the reason why placebo is not implemented may be related to the characteristics of Chinese herbs including appearance, taste, and smell [99]. Drop-out was only reported in 3 trials, and most of the trials havenot reported intention to treat analysis in details. Thus, results generated from these trials should be interpreted with caution. Additionally, most of the trials were small sample size and single-center. None of the trials have reported the sample size estimation, which placed the statistical analysis's validity in doubt.

Secondly, only 8 out of 22 trials mentioned the adverse effects, and most of the trials havenot realized the importance of adverse effects of either Chinese herbal formula or herb-drug interaction. Herb-drug interaction, just botanical and chemical drugs, is an emerging issue of integrative medicine [100–104]. It has raised more and more concern. In this review, almost all the reported adverse events such as cough, vomiting, flushing, rash, and edema in combination group may partially be related to the adverse events of antihypertensive drugs. Thus, a definite conclusion about the safety of TGY combined with antihypertensive drugs still cannot be drawn.

Thirdly, zheng is a unique concept in TCM [105, 106]. It is identified from a comprehensive analysis of clinical information by TCM practitioner from four main diagnostic TCM methods: observation, listening, questioning, and pulse analyses [107]. In other words, zheng classification is a traditional diagnostic method to categorize patients based on their different conditions. All diagnostic and therapeutic methods in TCM are based on the differentiation of TCM syndrome, and this concept has been used for thousands of years in China [108]. Clinical trials based on TCM zheng classification may lead to more valid conclusions about Chinese herbal formula [109–114]. In our review, TGY combined with antihypertensive drugs appeared to be more effective than antihypertensive drugs alone for LYHS and LKYDS in EH. However, 3 trials did not provide detailed information about TCM diagnostic criteria, and only 9 trials used TCM zheng to evaluate treatment effects as the other outcome measure. Thus, clear diagnostic criteria and objective evaluation of TCM zheng are warranted in further clinical trials.

In conclusion, this is the first zheng classification-based meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials to assess the efficacy and safety of TGY as adjunctive treatment in patients with EH. However, current clinical evidence of TGY for EH with LYHS and LKYDS was so weak. More rigorous trials with high quality are needed to generate high level of evidence and confirm the results.

Conflict of Interests

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Authors' Contribution

J. Wang, B. Feng, X. Yang, W. Liu, Y. Liu, Y. Zhang, G. Yu, S. Li, and Y. Zhang contributed equally to this paper.

Acknowledgments

The current work was partially supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, no. 2003CB517103) and the National Natural Science Foundation Project of China (no. 90209011). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the paper.

References

- 1.Sliwa K, Stewart S, Gersh BJ. Hypertension: a global perspective. Circulation. 2011;123(24):2892–2896. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.992362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension. The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Journal of Hypertension. 2007;25(6):1105–1187. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3281fc975a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu Y, Huxley R, Li L, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China data from the China National Nutrition and Health Survey 2002. Circulation. 2008;118(25):2679–2686. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.788166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gu D, Reynolds K, Wu X, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China. Hypertension. 2002;40(6):920–927. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000040263.94619.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mancia G, Laurent S, Agabiti-Rosei E, et al. Reappraisal of European guidelines on hypertension management: a European Society of Hypertension Task Force document. Journal of Hypertension. 2009;27(11):2121–2158. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328333146d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alderman MH, Ogihara T. Global challenge for overcoming high blood pressure: Fukuoka Statement, 19 October 2006. Journal of Hypertension. 2007;25(3):p. 727. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3280961a1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Vander Hoorn S, Murray CJL. Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet. 2002;360(9343):1347–1360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365(9455):217–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17741-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacMahon S, Alderman MH, Lindholm LH, Liu L, Sanchez RA, Seedat YK. Blood-pressure-related disease is a global health priority. Lancet. 2008;371(9623):1480–1482. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60632-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yach D, Hawkes C, Gould CL, Hofman KJ. The global burden of chronic diseases: overcoming impediments to prevention and control. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291(21):2616–2622. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ôunpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases. Circulation. 2001;104:2855–2864. doi: 10.1161/hc4701.099488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawes CM, Hoorn SV, Rodgers A. Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001. Lancet. 2008;371(9623):1513–1518. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60655-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Whelton PK, He J. Worldwide prevalence of hypertension: a systematic review. Journal of Hypertension. 2004;22(1):11–19. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200401000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farsang C, Naditch-Brule L, Avogaro A, et al. Where are we with the management of hypertension? From science to clinical practice. Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2009;11(2):66–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.00066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baumhäkel M, Schlimmer N, Böhm M. Effect of irbesartan on erectile function in patients with hypertension and metabolic syndrome. International Journal of Impotence Research. 2008;20(5):493–500. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2008.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keene LC, Davies PH. Drug-related erectile dysfunction. Adverse Drug Reactions and Toxicological Reviews. 1999;18(1):5–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohamed IN, Helms PJ, Simpson CR, McLay JS. Using routinely collected prescribing data to determine drug persistence for the purpose of pharmacovigilance. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2011;51(2):279–284. doi: 10.1177/0091270010366444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheung F. TCM: made in China. Nature. 2011;480(7378, supplement):S82–S83. doi: 10.1038/480S82a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu H, Chen K. Integrative medicine: the experience from China. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2008;14(1):3–7. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.6329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crow JM. The healthy gut feeling. Nature. 2011;480(7378, supplement):S88–S89. doi: 10.1038/480S88a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu L. The clinical trial barriers. Nature. 2011;480(7378, supplement):p. S100. doi: 10.1038/480S100a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu H, Chen KJ. Complementary and alternative medicine: is it possible to be mainstream? Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2012;18(6):403–404. doi: 10.1007/s11655-012-1126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nahas R. Complementary and alternative medicine approaches to blood pressure reduction: an evidence-based review. Canadian Family Physician. 2008;54(11):1529–1533. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ernst E. Complementary/alternative medicine for hypertension: a mini-review. Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift. 2005;123:386–391. doi: 10.1007/s10354-005-0205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu MY, Chen KJ. Convergence: the tradition and the modern. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2012;18(3):164–165. doi: 10.1007/s11655-012-1014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen KJ. Where are we going? Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2010;16(2):100–101. doi: 10.1007/s11655-010-0100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park HL, Lee HS, Shin BC, et al. Traditional medicine in China, Korea, and Japan: a brief introduction and comparison. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012:9 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/429103.429103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tian P. Where west meets east. Nature. 2011;480(7378, supplement):S84–S86. doi: 10.1038/480S84a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu AP, Jia HW, Xiao C, Lu QP. Theory of traditional Chinese medicine and therapeutic method of diseases. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2004;10:1854–1856. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i13.1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiong XJ, Chu FY, Li HX, He QY. Clinical application of the TCM classic formulae for treating chronic bronchitis. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2011;31(1):69–72. doi: 10.1016/s0254-6272(11)60016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang M, Zhang C, Zheng G, et al. Traditional Chinese medicine Zheng in the era of evidence-based medicine: a literature analysis. Evidence-Based Complementary and AlternativeMedicine. 2012;2012:9 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/409568.409568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang M, Lu C, Zhang C, et al. Syndrome differentiation in modern research of traditional Chinese medicine. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2012;140:634–642. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang M, Zhang C, Cao H, Chan K, Lu A. The role of Chinese medicine in the treatment of chronic diseases in China. Planta Medica. 2011;77(9):873–881. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1270983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang J, Wang PQ, Xiong XJ. Current situation and re-understanding of syndrome and formula syndrome in Chinese medicine. Internal Medicine. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu AP, Jiang M, Zhang C, Chan K. An integrative approach of linking traditional Chinese medicine pattern classification and biomedicine diagnosis. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2012;141(2):549–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Xiong XJ. Current situation and perspectives of clinical study in integrative medicine in China. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012:11 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/268542.268542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen KJ. Clinical service of Chinese medicine. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2008;14(3):163–164. doi: 10.1007/s11655-008-0163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu AP, Chen KJ. Integrative medicine in clinical practice: from pattern differentiation in traditional Chinese medicine to disease treatment. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2009;15(2):p. 152. doi: 10.1007/s11655-009-0152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li H, Liu LT, Zhao WM, et al. Effect of traditional and integrative regimens on quality of life and early renal impairment in elderly patients with isolated systolic hypertension. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2010;16(3):216–221. doi: 10.1007/s11655-010-0216-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhong GW, Chen MJ, Luo YH, et al. Effect of Chinese herbal medicine for calming Gan and suppressing hyperactive yang on arterial elasticity function and circadian rhythm of blood pressure in patients with essential hypertension. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2011;17(6):414–420. doi: 10.1007/s11655-011-0761-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiong XJ, Yang XC, Liu W, et al. Banxia Baizhu Tianma decoction for essential hypertension: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012:10 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/271462.271462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J, Yao KW, Yang XC, et al. Chinese patent medicine liu wei di huang wan combined with antihypertensive drugs, a new integrative medicine therapy, for the treatment of essential hypertension: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012:7 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/714805.714805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu AP, Chen KJ. Chinese medicine pattern diagnosis could lead to innovation in medical sciences. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2011;17(11):811–817. doi: 10.1007/s11655-011-0891-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu H, Chen KJ. Integrating traditional medicine with biomedicine towards a patient-centered healthcare system. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2011;17(2):83–84. doi: 10.1007/s11655-011-0641-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang J, Xiong XJ. Control strategy on hypertension in Chinese medicine. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012:6 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/284847.284847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiang HQ, Li YL, Xie J. Urine metabonomic study on hypertension patients of ascendant hyperactivity of gan yang syndrome by high performance liquid chromatography coupled with time of flight mass spectrometry. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2012;32(3):333–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jin Y, Hu S, Yan D. Study on molecular mechanism of ganyang shangkang syndrome in hypertension. Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine. 2000;20(2):87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang CH, Lin JM, Xie J, Jiang HQ, Li YL. Study on the metabolin difference of hypertension patients of gan-yang hyperactivity syndrome and yin-yang deficiency syndrome. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2012;32(9):1204–1207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li WL, Chen XY, Wu XL. Effects of Tianma Gouteng decoction on mRNA expression of CaL-α1C and PM-CA1 in vascular smooth muscle cells of spontaneously hypertensive rat. Zhong Cheng Yao. 2009;31(8):1175–1179. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cai CL, Li MY, Xing ZH, Liu WP, Tan HY, Zhang C. Effects of Tianma Gouteng decoction on SOD and MDA in hypertensive patients with liver yang hyperactivity syndrome. Jia Ting Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2005;21(3):321–322. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin ZZ, Xing ZH, Cai CL, Tan HY, Zhang C. Effects of tianma gouteng decoction on the plasma endothelin of patients with primary hypertension of hyperactivity of the liver yang. Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation. 2004;8(27):5992–5993. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xing ZH, Cai CL, Tan HY, Lin ZZ. Effect of Tianma Gouteng decoction on the curative efficacy and quality of life in patients with essential hypertension. Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation. 2004;8(15):2880–2881. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mo XN, Yang YB, Huang SX, Liu JC. Effects of Tianma Gouteng decoction on vascular remodeling in hypertensive rat. Zhongguo Shi Yan Fang Ji Xue Za Zhi. 2011;17(9):149–152. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Duan XJ, Zeng X, Zhang X, Ou RM. Effects of Tianma Gouteng decoction on Ang II, ALD and liver protein expression in spontaneously hypertensive rats with liver yang hyperactivity syndrome. Zhongguo Shi Yan Fang Ji Xue Za Zhi. 2010;16(16):160–162. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun JH. Effect of Tianma Gouteng decoction on myocardial fibrosis in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Guangzhou Zhong Yi Yao Da Xue Xue Bao. 2008;25(5):438–441. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gong YP, Ni MW, Song XH, Cheng ZQ, Gu HP. Experimental study of Tianma Gouteng decoction on insulin resistance in spontaneously hypertensive rats with liver yang hyperactivity syndrome. Zhejiang Zhong Yi Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2005;29(2):62–64. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang QY, Sun HR. Effect and clinical significance of Tianma Gouteng decoction on TGF-β1 and Bcl-2 in patients with essential hypertension. Zhong Yi Yan Jiu. 2006;19(7):24–26. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin ZZ, Xing ZH. A clinical observation on the therapeutic effect of Tianma Gouteng decoction on the plasma level of endothelin among patients with hypertension. Hunan Zhong Yi Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2003;23(1):13–14. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu WP, Xing ZH, Lin ZZ. Effect of Tianma Gouteng decoction on plasma nitric oxide of the patients with essential hypertension. Zhongguo Kang Fu. 2003;18(5):291–292. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li YB, Cui M, Yang Y, et al. Similarity of traditional Chinese medicine formula. Zhong Hua Zhong Yi Yao Xue Kan. 2012;30(5):1096–1097. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] The Cochrane Collaboration, 2009, http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/

- 63.Wang SF, Li QF, Wang JG, Mei N. A clinical observation on the therapeutic effect of Dan Shao Tianma Gouteng decoction combined with captopril on hypertension. Heilongjiang Zhong Yi Yao. 1998;(4):10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ren BW, Zhao XM. Effect of modified Tianma Gouteng yin on 30 cases of essential hypertension with liver yang hyperactivity syndrome. Zhongguo Yao Ye. 2012;21(16):p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fu R. Effect of modified Tianma Gouteng yin on essential hypertension with liver yang hyperactivity syndrome. Liaoning Zhong Yi Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2005;7(6):p. 595. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qin FL. The Clinical effects comparision of Tianma Gouteng yin and Tianma Gouteng particle on treating hypertension. Zhongguo Dang Dai Yi Yao. 2010;17(10):72–73. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hu SY, Xian SX, Zhao LC, Yu Z, Wu YH, Qi YH. Effect of Tianma Gouteng yin decoction on serum procollagen III and aldosterone and angiotensin II in essential hypertension. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xin Nao Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2009;7(5):512–513. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sun JH, Huang XW. Clinical studies of Tianma Gouteng yin decoction combined with hydrochlorothiazide for the treatment of elderly patients with hypertension. Zhong Yao Xin Yao Yu Lin Chuang Yao Li. 2007;18(5):412–414. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang Q, Li F, Fang XM. Effect of Tianma Gouteng yin decoction and captopril on blood pressure and inflammatory factor in patients with essential hypertension. Zhong Yi Za Zhi. 2008;49(1):32–34. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fang XM, Li F, He JS, Wang Q. Effect of Tianma Gouteng yin decoction and captopril on 30 cases of hypertensive patients. Shanxi Zhong Yi. 2008;29(3):308–310. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li MX. A clinical observation on the therapeutic effect of modified Tianma Gouteng yin on 48 cases of essential hypertension with liver yang hyperactivity syndrome. Jilin Zhong Yi Yao. 2006;26(5):15–16. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu YF. Effect of Tianma Gouteng yin decoction combined with amlodipine on hypertension with liver yang hyperactivity syndrome. Shenzhen Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2011;21(4):239–241. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu CB, Wang LJ, Ren HB, Jiang XC. Effect of Tianma Gouteng yin decoction combined with perindopril on 30 cases of hypertension. Zhong Yi Yao Xue Bao. 2009;37(1):55–56. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen XJ. Effect of Tianma Gouteng yin decoction combined with captopril on 50 patients with essential hypertension. Shanxi Zhong Yi. 2009;30(6):681–683. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang SY, Yang XY. A clinical observation on the therapeutic effect of Tianma Gouteng yin decoction combined with western medicine on hypertension with anxiety. Tianjin Zhong Yi Yao. 2011;28(3):191–193. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu LY, Li R. A clinical observation on the therapeutic effect of Tianma Gouteng yin decoction on 100 cases of hypertension with liver yang hyperactivity syndrome. Ya Tai Chuan Tong Yi Yao. 2011;7(6):58–59. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wei YL. Effect of Tianma Gouteng yin decoction on 49 cases of hypertension with liver yang hyperactivity syndrome. Shenzhen Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2012;22(5):310–312. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li MF. A clinical observation on the therapeutic effect of Tianma Gouteng yin decoction on 120 cases of hypertension with liver yang hyperactivity syndrome. Zhong Yi Yao Dao Bao. 2011;17(7):38–39. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lin JZ, Liu YY. A clinical observation on the therapeutic effect of Tianma Gouteng yin decoction on hypertension of young and middle-aged. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xin Nao Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2010;8(6):p. 649. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhou YL, Zhang YK. Effect of integrative medicine on 36 cases of essential hypertension with liver yang hyperactivity syndrome. Shanxi Zhong Yi. 2011;27(2):p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen XJ. The clinical observation on high blood pressure with combined treatment of traditional Chinese medicine and western medicine: a report of 50 cases. Shanxi Zhong Yi. 2008;24(7):27–28. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Du WX. Effect of integrative medicine on 50 cases of essential hypertension. Hunan Zhong Yi Za Zhi. 2012;28(4):30–31. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cheng M. A clinical observation on the therapeutic effect of integrative medicine on 50 cases of essential hypertension. Zhong Yi Yao Dao Bao. 2010;16(9):46–47. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhu XQ. Clinical effects on integrative Chinese and western medicine in treating essential hypertention. Hunan Zhong Yi Yao Da Xue Xue Bao. 2009;29(12):67–69. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xu H, Chen KJ. Making evidence-based decisions in the clinical practice of integrative medicine. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2010;16(6):483–485. doi: 10.1007/s11655-010-0560-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xiong XJ. Study on the history of formulas corresponding to syndromes. Journal of Chinese Integrative Medicine. 2010;8(6):581–588. doi: 10.3736/jcim20100612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kim JI, Choi JY, Lee H, Lee MS, Ernst E. Moxibustion for hypertension: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 2010;10, article 33 doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-10-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang J, Yang XC, Feng B, et al. Is Yangxue Qingnao Granule combined with antihypertensive drugs, a new integrative medicine therapy, more effective than antihypertensive therapy alone in treating essential hypertension? Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;2013:8 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/540613.540613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee MS, Choi TY, Shin BC, Kim JI, Nam SS. Cupping for hypertension: a systematic review. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension. 2010;32(7):423–425. doi: 10.3109/10641961003667955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lee MS, Pittler MH, Taylor-Piliae RE, Ernst E. Tai chi for cardiovascular disease and its risk factors: a systematic review. Journal of Hypertension. 2007;25(9):1974–1975. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32828cc8cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Xiong XJ, Yang XC, Feng B, et al. Zhen gan xi feng decoction, a traditional Chinese herbal formula, for the treatment of essential hypertension: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;2013:9 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/982380.982380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee MS, Pittler MH, Guo R, Ernst E. Qigong for hypertension: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Journal of Hypertension. 2007;25(8):1525–1532. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328092ee18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee MS, Lee EN, Kim JI, Ernst E. Tai chi for lowering resting blood pressure in the elderly: a systematic review. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2010;16(4):818–824. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Xiong XJ, Yang XC, Liu YM, Zhang Y, Wang PQ, Wang J. Chinese herbal formulas for treating hypertension in traditional Chinese medicine: perspective of modern science. Hypertension Research. 2013 doi: 10.1038/hr.2013.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang HW, Tong J, Zhou G, Jia H, Jiang JY. Tianma Gouteng Yin Formula for treating primary hypertension. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;(6) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008166.pub2.CD008166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dong DX, Yao SL, Yu N, Yang B. Systematic review and meta-analysis of Tianma Gouteng Yin combined with enalapril for essential hypertension. Zhongguo Zhong Yi Ji Zheng. 2011;20(5):762–764. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kaptchuk TJ. The placebo effect in alternative medicine: can the performance of a healing ritual have clinical significance? Annals of Internal Medicine. 2002;136(11):817–825. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-11-200206040-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Brody H, Miller FG. Lessons from recent research about the placebo effect: from art to science. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;306(23):2612–2613. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chen W, Danforn Lin CE, Kang HJ, Liu JP. Chinese herbal medicines for the treatment of Type A H1N1 Influenza: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Plos ONE. 6(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028093.e28093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wang J, Xiong XJ. Outcome measures of Chinese herbal medicine for hypertension: an overview of systematic reviews. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012:7 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/697237.697237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Xiong XJ, Wang J. Discussion of related problems in herbal prescription science based on objective indications of herbs. Journal of Chinese Integrative Medicine. 2010;8(1):20–24. doi: 10.3736/jcim20100104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Xu H, Chen KJ. Herb-drug interaction: an emerging issue of integrative medicine. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2010;16(3):195–196. doi: 10.1007/s11655-010-0195-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Xiong XJ, Wang J, He QY. Application status and safety countermeasures of traditional Chinese medicine injections. Journal of Chinese Integrative Medicine. 2010;8(4):307–311. doi: 10.3736/jcim20100402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Xiong X, Wang J, He Q. Thinking about reducing adverse reactions based on idea of formula corresponding to syndromes. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 2010;35(4):536–538. doi: 10.4268/cjcmm20100429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lu AP, Bian ZX, Chen KJ. Bridging the traditional Chinese medicine pattern classification and biomedical disease diagnosis with systems biology. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2012;18(12):883–890. doi: 10.1007/s11655-012-1290-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ferreira A. Integrative medicine for hypertension: the earlier the better for treating who and what are not yet ill. Hypertension Research. 2013 doi: 10.1038/hr.2013.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Jiang M, Yang J, Zhang C, et al. Clinical studies with traditional Chinese medicine in the past decade and future research and development. Planta Medica. 2010;76(17):2048–2064. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1250456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lu AP, Ding XR, Chen KJ. Current situation and progress in integrative medicine in China. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2008;14(3):234–240. doi: 10.1007/s11655-008-240-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lu C, Xiao C, Chen G, et al. Cold and heat pattern of rheumatoid arthritis in traditional Chinese medicine: distinct molecular signatures indentified by microarray expression profiles in CD4-positive T cell. Rheumatology International. 2012;32:61–68. doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1546-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Xiong XJ, Wang J. Explaining syndromes of decoction for removing blood stasis in chest. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2011;36(21):3026–3031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jiang M, Xiao C, Chen G, et al. Correlation between cold and hot pattern in traditional Chinese medicine and gene expression profiles in rheumatoid arthritis. Frontiers of Medicine. 2011;5(2):219–228. doi: 10.1007/s11684-011-0133-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Xiong X, Wang J. Thought and method of treating dyslipidemia. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 2010;35(10):1349–1351. doi: 10.4268/cjcmm20101029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Xiong XJ, Wang J. Experience of diagnosis and treatment of exogenous high-grade fever. Journal of Chinese Integrative Medicine. 2011;9(6):681–687. doi: 10.3736/jcim20110616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Shin BC, Kim S, Cho YH. Syndrome pattern and its application in parallel randomized controlled trials. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2013;19(3):163–171. doi: 10.1007/s11655-012-1256-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]