Abstract

The origin of stereoselectivity of NHC-catalyzed annulation reactions of ynals and stable enols was studied with Density Functional Theory. The data suggest that the C-C bond formation is the stereo-determining step. Only the deprotonated pathway (containing an oxy anion and overall neutral species) was found to give rise to discrimination of the competing stereoisomers. This is due predominantly to electrostatic repulsion of the β-stabilizing enolate functionality with the π-cloud of the aryl group in the NHC-catalyst.

Introduction

N-heterocyclic carbenes are widely used in synthesis to achieve enantioselective transformations.1 In this context, Bode and co-workers developed an annulation reaction of ynals and stable enols (see in Scheme 1). Their mechanistic studies2 established that the triazolium salt precatalyst is initially deprotonated by a general base to generate the active NHC. This species then adds irreversibly to the aldehyde 2 to form an adduct that leads to the α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium species 8 (see Figure 1) (after proton transfer and internal redox reaction). Lupton3 et al. reported a related NHC-catalyzed annulation of α,β-unsaturated acyl fluorides and enol silanes using achiral imidazolium-derived NHCs, a process thought to also occur via an unsaturated acyl azolium. Xiao,4 Studer,5 and You6 have also reported similar annulation cascades.

Scheme 1.

Annulation reactions by Bode et al.2a

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanism of annulations reaction involving a Claisen rearrangement as key C-C bond forming event.

Bode and co-workers performed detailed kinetic investigations on the annulation reaction involving kojic acid 4 (shown in Scheme 1). Their data suggested that the annulation process did not proceed via 1,4-addition of the enol to the catalytically generated α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium, but rather support a preassociation followed by Claisen-type rearrangement as the key catalytic step (see Figure 1).2c A prerequisite for this Claisen rearrangement is the initial formation of hemiacetal 9 via 1,2 addition of the enol (or enolate) to the α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium species 8. Indicative of this is the fact that esterification side-reactions have been observed with related catalyst frameworks that would be expected to occur via initial 1,2-addition.2 However, as discussed previously by Bode et al.2c,d and also by Coates and Curran7 in their seminal mechanistic work, the kinetic data would also be consistent with the alternative scenario of breakdown of the hemiacetal to a tight ion pair, followed by a stepwise carbon–carbon bond forming process through a highly organized transition state.

Several mechanistic questions remained unanswered in the previous analyses:2d (i) the origins of the high levels of enantioinduction in these NHC-catalyzed annulation reactions are unknown. The stereochemistry could in principle be established when hemiacetal 9 is formed or in the subsequent C–C bond-forming event and (ii) the protonation states (indicated in red color in Figure 1) of the various intermediates and transition states are unknown.

We herein report our computational studies to elucidate the origins of stereoselectivity of the NHC-catalyzed annulation reactions shown in Scheme 1. We also provide insights on the favored protonation states and discuss additional mechanistic information that were previously inaccessible through kinetic studies.

Results and Discussion

To gain insights on the origin of stereoselectivity of this NHC-catalyzed transformation, we performed DFT investigations on the key intermediates and transition states.8 We studied the transformations of two substrates, keto ester 3 and kojic acid 4.9 As discussed above, the formation of acyl azolium species 8 occurs first (Figure 1). Experimentally, only the E-stereoisomer of 8 has been observed under the reaction conditions applied.2a This is in agreement with our computational results: the Z-isomer was calculated to be 5.8 kcal/mol higher in energy than the corresponding E-isomer.10 Therefore, only the E-isomer will be considered.

We next studied the formation of postulated hemiacetal 9, following attack by the enol 7 derived from ketoester 3. (We will discuss the results for ketoester 3 first and those for kojic acid 4 will follow later, see below). This may occur via Si or Re face-attack to the acyl azolium 8 and could give rise to a protonated or deprotonated species. Previous kinetic investigations established that the 1,2-addition has a lower activation barrier than the later C-C bond forming event to give 10.2c,d Moreover, we calculated that the 1,2-addition to form the protonated hemiacetal is only slightly exergonic (ΔGrxn= −2.2 kcal/mol for the addition of the enol derived from 3 to acyl azolium 8 in toluene10). For the protonated pathway, the 1,2-addition is therefore a reversible process. Figure 2 shows the minimum energy conformations of the two possible diastereomeric intermediates, featuring R- or S-stereochemistry at the central chiral carbon highlighted in green. (References 11 and 12 give information on the computational approach). These structures feature a distinct intramolecular OH•••O=C hydrogen bond and the corresponding relative energy difference is given in Table 1. There is essentially no preference of R versus S stereochemistry in the protonated hemiacetal 9; an energy difference of only ΔH=0.1–0.3 kcal/mol was obtained (see Table 1).

Figure 2.

Minimum energy conformations of the hemiacetal intermediates (9) derived from keto ester 3 calculated at ωB97XD/6-31G(d) (toluene).11 The R and S stereochemical descriptors refer to the carbon highlighted in green.

Table 1.

ΔH preference for S-stereochemistry of the protonated hemiacetal 9 derived from keto ester 3 at 313.15 K.

| System | Method | ΔH (R-S) |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | M06-2X/6-31++G(d,p)a//B3LYP/6-31G(d)a | 0.1 |

| 3 | B3LYP/6-31++G(d,p)a//B3LYP/6-31G(d)a | 0.3 |

| 3 | M06-2X/6-31++G(d,p)a//ωB97XD/6-31G(d)a | −0.1 |

| 3 | ωB97XD/6-31G(d)a | 0.2 |

Using CPCM (toluene) for optimization and energies.

For the deprotonated analogs of hemiacetal 9 (which are overall neutral species), all attempts to locate stable intermediates on the potential energy surface were unsuccessful with the computational approach chosen [optimization involving the implicit solvation model CPCM (toluene) and ωB97XD/6-31G(d) or ωB97XD/6-311++G(d,p)]. Instead, an ion pair was obtained. We believe that this is due to the implicit solvation model that does not capture the true stabilization offered by real solvent molecules in solution. Indeed, when we optimized the deprotonated hemiacetals 9 in the presence of a water molecule or methane (as an extreme mimic of the solvent used in the reaction: toluene), we were able to locate true hemiacetal intermediates. The structures are given in the supporting information in Figures S1–S3 on pages S64–S70. However, as with the protonated analoges, the R and S isomers have essentially the same energies.13 Regardless of the protonation state of the hemiacetal, the subsequent irreversible C–C bond forming event should therefore control the overall stereochemical outcome of the transformation.

We subsequently studied the transition states (TSs) of the corresponding Claisen rearrangement derived from hemiacetal 9 for the keto ester system. It is widely accepted that chair transition states are generally preferred over the boat transition states in [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangements.14 Boat transition states are less common, but Ireland-Claisen transformations have been identified that preferentially proceed via boat TSs.15 Our calculations of the protonated boat and chair transition states derived from the R- and S-hemiacetals 9 gave a strong preference for the chair transition states [by > 5 kcal/mol over the corresponding boat TSs].16 The stereochemical outcome of the reaction should therefore be controlled by the differences in chair TS energies. Figure 3 illustrates the minimum energy chair transition states of the Claisen rearrangements derived from R- and S-9 for the keto ester system (3). Notably, the π-π-interaction between the α,β- unsaturated moiety and the catalyst aryl group that was favored in the intermediates (Figure 2) is not favored in the transition states. Some C-H–π interaction is gained in the TS however. The energy differences between R- and S-chair TSs at various levels of theory are summarized in Table 2. Remarkably, essentially the identical energy was calculated for R- and S-stereochemistry at all levels of theory applied (R, S refer to the stereochemistry of the central carbon highlighted in green). Considering the reaction conditions applied (40°C), multiple competitive transition state conformations could in principle be reactive. We therefore also considered a range of different TS conformations for R- and S-chair TSs and sampled 20 transition state conformations in each case.17 Using B3LYP/6-31G(d) energies, we calculated the Boltzmann weighted average for each TS ensemble at 40°C (see supporting information on page S73 for detailed information). Breslow, Friesner et al. recently applied a similar analysis for alkene epoxidation reactions.18 For the two ensembles, essentially, the identical average energy was calculated (ΔEaver=0.04 kcal),19 reinforcing our previous results, i.e. that no stereoinduction is predicted for R-versus S-chair TSs in their protonated states.

Figure 3.

Claisen chair TSs, calculated at M06-2X/6-31++G(d,p) (toluene)//B3LYP/6-31G(d) (toluene). The R and S stereo descriptors refer to the carbon highlighted in green. ΔΔH‡ given in Table 2.

Table 2.

ΔΔH‡ preference for R-chair TS for keto-ester 3 at 313.15 K.

| Chair-TS of | Method | ΔΔH‡ (R-S) |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | M06-2X/6-31++G(d,p)a//ωB97XD/6-31G(d)a | −0.4 |

| 3 | ωB97XD/6-31G(d) a | 0.0 |

| 3 | B3LYP/6-31G(d)a | −0.3 |

Optimization and energies calculated with CPCM (toluene).

As we do not predict any stereoinduction above, this suggests that the true stereodetermining transition state might not involve a proton (as illustrated in red, Figure 1), and the reaction in fact proceeds via the deprotonated analogue, resulting from the attack by an enolate (rather than enol) to the azolium intermediate 8 (see Figure 2). Calculations of the corresponding zwitterionic transition states for R- versus S-stereochemistry now indeed predict the chair TS featuring R-stereochemistry to be favored over the corresponding S-chair TS by ΔΔH‡ = 1.8 kcal/mol (at M06-2X/6-31++G(d,p)(toluene)//ωB97XD/6-31G(d) (toluene) level of theory; see Table S1 on page S73 in the SI for other methods also). This is consistent with the experimentally observed R-stereochemistry in the final product 5 and supports the deprotonated, overall neutral reaction pathway as the stereo- determining path. Figure 4 illustrates the lowest energy conformers of the R- and S-chair TSs*.20,21

Figure 4.

Transition states for the deprotonated, zwitterionic pathway for keto ester system 3. The R- and S-stereochemical descriptors refer to the carbon highlighted in green. ΔΔH‡ = 1.8 kcal/mol [at M06-2X/6-31++G(d,p) (toluene)//ωB97XD/6-31G(d)(toluene)].21

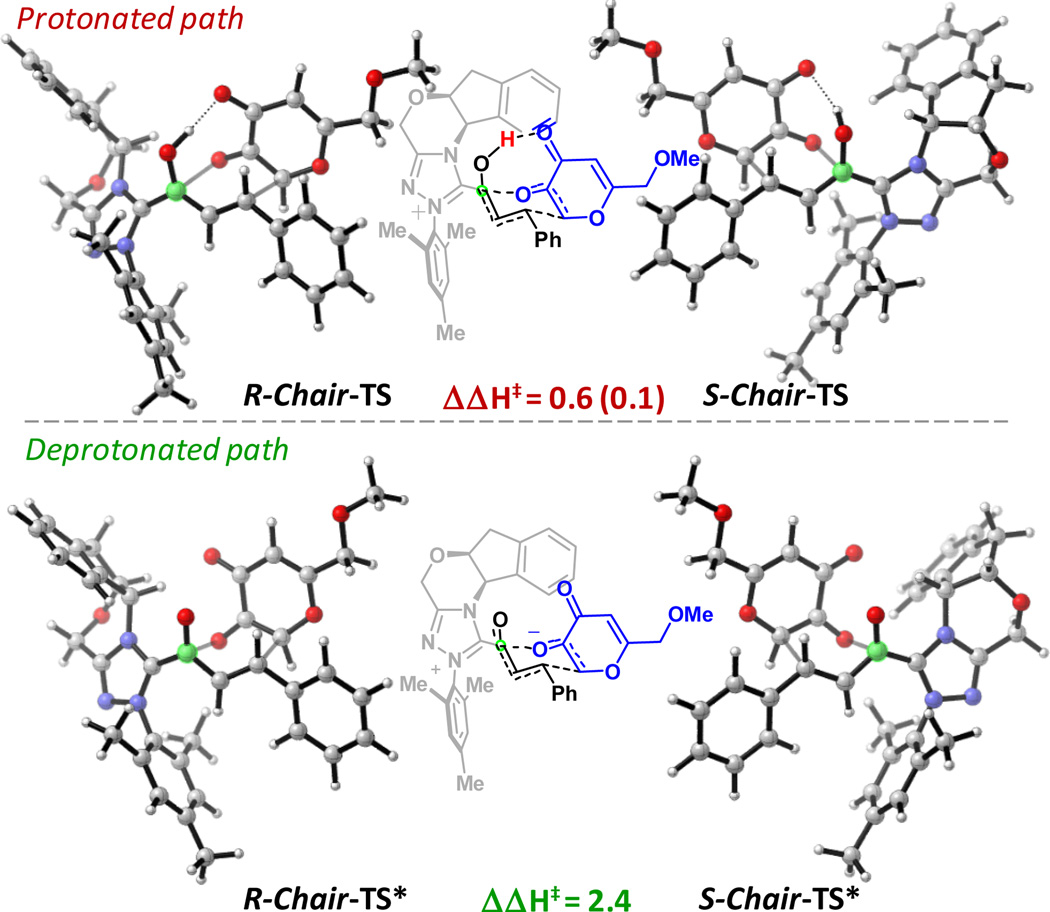

We also studied the stereoinduction for an alternative substrate, kojic acid 4. We obtained analogous results, in that the protonated pathway also does not give rise to a substantial difference in energies of the different stereochemical pathways (see Figure 5). Again, only the deprotonated, zwitterionic TSs differ in energy. Figure 5 shows the lowest energy transition states for R- and S- stereochemistry in the protonated (TS) and deprotonated (TS*) versions. An enthalpy of activation difference of 2.4 kcal/mol (ΔΔH‡) was calculated for the deprotonated TSs* [at M06-2X/6-31++G(d,p) (toluene)//ωB97XD/ 6-31G*(toluene) level of theory], favoring R-chair-TS* once again.21 Note, due to nomenclature reasons, the R-chair TS leads to S-stereochemistry in the final product 6 for kojic acid 4.

Figure 5.

S- and R-TSs for the protonated (=TS, top) and deprotonated (=TS*, bottom) pathways for kojic acid system 4. The R- and S-stereochemical descriptors refer to the carbon in green. ΔΔH‡ = 2.4 kcal/mol [at M06-2X/6-31++G(d,p) (toluene)//ωB97XD/6-31G(d) (toluene)] for deprotonated pathway. Energies in kcal/mol at 313.15 K; CPCM (toluene) B3LYP/6-31G(d) enthalpy given in parenthesis.21

The displacement vectors of the anionic transition states show a small displacement along O•••C=O, in line with expected movements for a [3,3]-sigmatropic TS, but the displacement is not as pronounced as for the Claisen TS in the protonated version. However, following the intrinsic reaction coordinate, followed by minimization in the presence of CH4 or H2O for charge stabilization on the oxygen (to approximate stabilization experienced in solution through solvent molecules, see above discussion), did give rise to the deprotonated hemiacetal 9 in a complex with CH4 or H2O (see supporting information, page S66–S72) and the expected product 10 (Figure 1), in line with a sigmatropic rearrangement. Notably, a conjugate addition would give the analogous TS arrangement due to favorable electrostatic interaction between the enolate oxygen and carbonyl group (O•••C=O). The transformation with this substrate class represents a special case in which Claisen and conjugate addition appear to have the analogous overall transition state configurations.22 The ultimate mechanistic classification depends on the intermediates that are formed, an ion pair or hemiacetal. Given the labile nature of the deprotonated hemiacetal, a mechanistic differentiation is essentially unnecessary, as both pathways are likely to occur in parallel. Bode and co-workers’ kinetic data clearly suggest a preorganization event, which is consistent with an initial, reversible 1,2-addition event that decomposes to a tight ion pair.2c

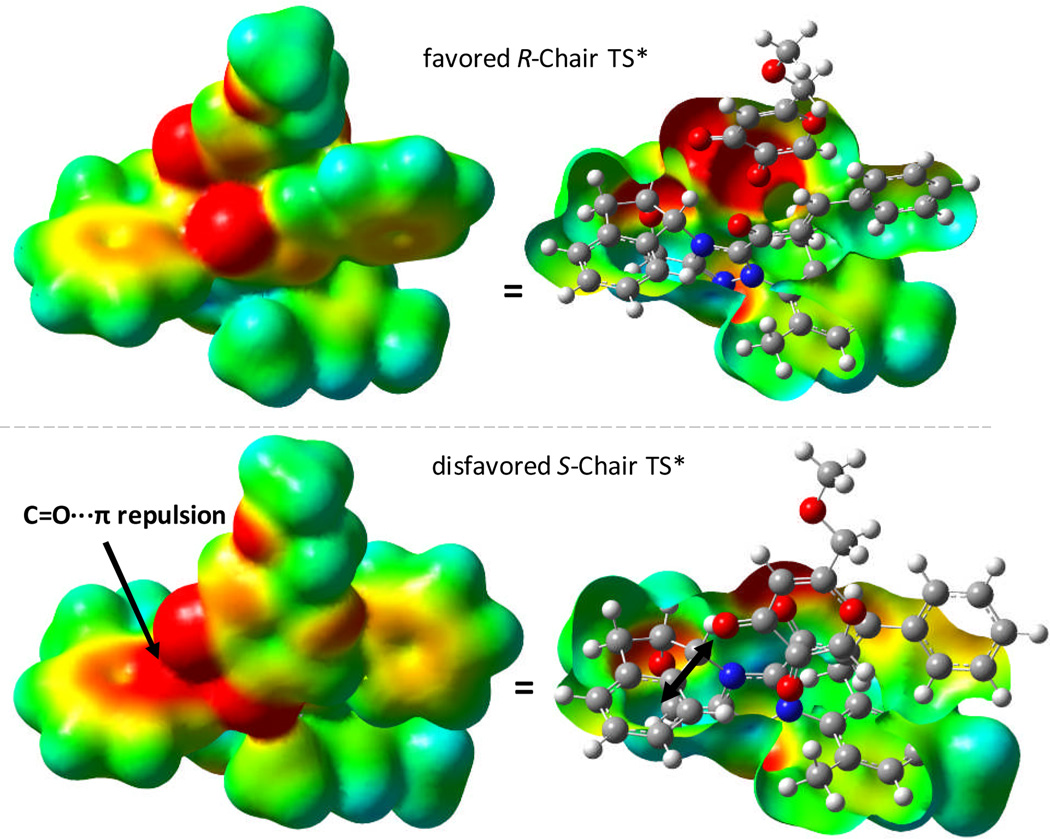

To understand the origin of stereoinduction in the deprotonated pathway, we calculated the electrostatic potential surfaces of the kojic acid (4) derived R- and S-TSs* (deprotonated). Figure 6 illustrates the results. The S-chair TS* suffers from a repulsive interaction of the negatively polarized β-oxygen in the enolate with the negative π-cloud of the aryl group in the catalyst (strongly red surface = negative potential). The latter repulsion is absent for the R-chair TS, however, or when a proton is present that quenches the negative charge density. In line with these conclusions is the fact that substrates that do not bear an α-carbonyl group and for which the discussed electrostatic repulsion is absent, such as 2-naphthol, give lower ee in experiments conducted by Bode et al. (68% ee, 79% yield).2c

Figure 6.

Electrostatic potential surfaces of R- (top) and S-chair (bottom) Claisen TSs* for the deprotonated pathway for kojic acid system 4, calculated at B3LYP/6-31G* [range: −4.885e-2 to 7.885e-2] with red corresponding to negative and blue to positive charge density.

Conclusions

The origin of stereoselectivity of NHC-catalyzed annulation reactions of α,β-unsaturated acyl azoliums and stable enols was studied with Density Functional Theory. Only the deprotonated pathway (containing an oxy anion and overall neutral species) was found to give rise to discrimination of the competing stereoisomers. This is due predominantly to electrostatic repulsion of the β-stabilizing enolate functionality with the π-cloud of the aryl group in the NHC-catalyst. For the investigated substrate class, both the Claisen rearrangement and the conjugate addition transition state configurations are essentially equivalent and the stereochemical model is general for either mechanism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Swiss National Science Foundation and ETH Zürich for financial support. Portions of this work were supported by the NIH (GM–079339). Calculations were performed on the ETH High-Performance Cluster Brutus.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: giving computational details, absolute energies, thermochemistry, and Cartesian coordinates of all calculated structures; full reference 8. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

References

- 1.For general reviews of NHC chemistry, see Nair V, Menon RS, Biju AT, Sinu CR, Paul RR, Jose A, Sreekumar V. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:9885. Chiang P-C, Bode JW. N-Heterocyclic Carbenes; The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2011:399–435. Moore JL, Rovis, T. T. Top. Curr. Chem.; B. List, Ed. Vol. 291. Springer; 2009. pp. 77–144. Nair V, Vellalath S, Babu BP. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:2691–2698. doi: 10.1039/b719083m. Enders D, Niemeier O, Henseler A. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:5606. doi: 10.1021/cr068372z.

- 2.a) Mahatthananchai J, Zheng P, Bode JW. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:1673. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Mahatthananchai J, Bode JW. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:192. doi: 10.1039/C1SC00397F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kaeobamrung J, Mahatthananchai J, Zheng P, Bode JW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:8810. doi: 10.1021/ja103631u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Mahatthananchai J, Kaeobamrung J, Bode JW. ACS Catalysis. 2012;2:494. doi: 10.1021/cs300020t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ryan SJ, Candish L, Lupton DW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:14176. doi: 10.1021/ja905501z. Candish L, Lupton DW. Org. Lett. 2010;12:4836. doi: 10.1021/ol101983h. Ryan SJ, Candish L, Lupton DW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:4694. doi: 10.1021/ja111067j. d) for mechanistic and computational studies: Ryan SJ, Stasch A, Paddon-Row MN, Lupton DW. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:1113. doi: 10.1021/jo202500k.

- 4.a) Zhu ZQ, Xiao JC. Adv. Syn. Catal. 2010;352:2455–2458. [Google Scholar]; b) Zhu ZQ, Zheng X-L, Jiang N-F, Wan X, Xiao J-C. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:8670–8672. doi: 10.1039/c1cc12778k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) De Sarkar S, Studer A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:9266–9269. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Biswa A, Sarkar SD, Frohlich R, Studer A. Org. Lett. 2011;13:4966–4969. doi: 10.1021/ol202108a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Guin J, De Sarkar S, Grimme S, Studer Grimme. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:8727. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rong Z-Q, Jia M-Q, You S-L. Org. Lett. 2011;13:4080–4083. doi: 10.1021/ol201595f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coates RM, Rogers BD, Hobbs SJ, Peck DR, Curran DP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:1160. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Using Gaussian09, Revision A.01; M. J. Frisch et al. [see SI for full reference].

- 9.We used OMe instead of OTBDMS in the calculations.

- 10.Calculated at M06-2X/6-31++G(d,p)//B3LYP/6-31G(d).

- 11.We performed a molecular mechanics based conformational search [using the OPLS-AA force field as implemented in MacroModel (©Schrodinger, Inc.)] on the protonated hemiacteal 9. All conformers obtained within an 8 kcal/mol energy range were then optimized with B3LYP/6-31G(d). The lowest energy conformers were subsequently optimized using an implicit solvation model (CPCM, for toluene) and the B3LYP or ωB97XD functionals with 6-31G(d) basis set and further refined through additional manual conformational search. CPCM (toluene) M06-2X/6-31++G(d,p) energies were calculated and corrected for 313.15 K. The latter computational approach was recently shown to be adequate by Clark et al.: Schenker S, Schneider C, Tsogoeva SB, Clark T. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011;7:3586–3595. doi: 10.1021/ct2002013.

- 12. Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. Theor. Chem. Acc., . 2008;120:215. Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:157. doi: 10.1021/ar700111a. For recent use of M06 in the study of organocatalytic transformations, see: Uyeda C, Jacobsen EN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:5062. doi: 10.1021/ja110842s. Um JM, DiRocco DA, Noey EL, Rovis T, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:11249. doi: 10.1021/ja202444g. DiRocco DA, Noey EL, Houk KN, Rovis T. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:2391. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107597.

- 13.The deprotonated hemiacetals were optimized in the presence of H2O. For R-, S-isomers, a difference of ΔGR-S=0.2 kcal/mol (ΔH=0.9) in slight favor of S was calculated at ωB97XD /6-31G(d) (toluene).

- 14.a) Rehbein J, Hiersemann M. The Claisen Rearrangement. Wiley-VCH; 2007. p. 525. [Google Scholar]; b) Doering WvE, Roth WR. Tetrahedron. 1962;18:67. [Google Scholar]; c) Hill RK, Gilman NW. Chem. Commun. 1967:619–620. [Google Scholar]; d) Hrovat DA, Borden WT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:4069. doi: 10.1021/ja004209o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Doering WvE, Toscano VG, Beasley GH. Tetrahedron. 1971;27:5299. [Google Scholar]; f) Goldstein MJ, Benzon MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:5119. [Google Scholar]; g) Goldstein MJ, Benzon MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:7147. [Google Scholar]; h) Rehbein J, Leick S, Hiersemann M. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:1531. doi: 10.1021/jo802303m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Kirsten M, Rehbein J, Hiersemann M, Strassner T. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:4001. doi: 10.1021/jo062455y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Chen C, Namba K, Kishi Y. Org. Lett. 2009;11:409. doi: 10.1021/ol8027225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Khaledy MM, Kalani MYS, Khuong KS, Houk KN, Aviyente V, Neier R, Soldermann N, Velker J. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:572. doi: 10.1021/jo020595b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Gül S, Schoenebeck F, Aviyente V, Houk KN. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:2115. doi: 10.1021/jo100033d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The boat TSs are given in the SI (pages S2; S33: S54; S57).

- 17.The forming/breaking bonds of the TS geometry were frozen, and a conformational search was then done using MacroModel. The TS conformers were subsequently optimized at B3LYP/6-31G(d) without any constraints and verified as true TSs.

- 18.Schneebeli ST, Hall ML, Breslow R, Friesner RJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3965. doi: 10.1021/ja806951r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.As a first approximation, we considered only electronic energies for this approach under the assumptions of equivalent enthalpy and -T?S corrections for the stereoisomers. See also: a) reference 18; b) for examples of use of ΔΔH‡ or ΔΔE‡ to rationalize selectivities, see: Cheong PH-Y, Legault CY, Um JM, Celebi-Olcum N, Houk KN. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:5042. doi: 10.1021/cr100212h.

- 20.The protonated pathway has an activation free energy barrier of ΔG‡ = 23.4 kcal/mol for the rearrangement of the protonated hemiacteal [at CPCM (toluene) ωB97XD/6-31G(d)]. The barrier for the deprotonated pathway is more difficult to determine, as determination of the true stabilization of the charged precursor species and their counter-ions through the solvent is a challenge for computational considerations. Relative to a pre-organized tight ion-pair complex, however, the barrier is small: ΔG‡= 2.0 kcal/mol.Related to that, it is well-established that the anionic oxy-cope rearrangement is very rapid: Evans dA, Golob AM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;97:4765. Paquette AL. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:13971. Gajewski JJ, Gee KR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:967.

- 21.Table S1 on page S73 in the supporting information summarizes ΔΔH‡ and ΔΔG‡ preferences for R-Chair TS in the deprotonated pathway for various alternative methods.

- 22.Ess DH, Wheeler SE, Iafe RG, Xu L, Celebi-Ölcum N, Houk KN. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:7592. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.