Abstract

Though difficult, the study of gene-environment interactions in multifactorial diseases is crucial for interpreting the relevance of non-heritable factors and prevents from overlooking genetic associations with small but measurable effects. We propose a “candidate interactome” (i.e. a group of genes whose products are known to physically interact with environmental factors that may be relevant for disease pathogenesis) analysis of genome-wide association data in multiple sclerosis. We looked for statistical enrichment of associations among interactomes that, at the current state of knowledge, may be representative of gene-environment interactions of potential, uncertain or unlikely relevance for multiple sclerosis pathogenesis: Epstein-Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, cytomegalovirus, HHV8-Kaposi sarcoma, H1N1-influenza, JC virus, human innate immunity interactome for type I interferon, autoimmune regulator, vitamin D receptor, aryl hydrocarbon receptor and a panel of proteins targeted by 70 innate immune-modulating viral open reading frames from 30 viral species. Interactomes were either obtained from the literature or were manually curated. The P values of all single nucleotide polymorphism mapping to a given interactome were obtained from the last genome-wide association study of the International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium & the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium, 2. The interaction between genotype and Epstein Barr virus emerges as relevant for multiple sclerosis etiology. However, in line with recent data on the coexistence of common and unique strategies used by viruses to perturb the human molecular system, also other viruses have a similar potential, though probably less relevant in epidemiological terms.

Introduction

As in other multifactorial diseases, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are providing important data about disease-associated loci in multiple sclerosis (MS) [1]. In parallel, sero-epidemiological studies are reinforcing the evidence that nonheritable factors such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and vitamin D are associated with disease pathogenesis [2].

However, the effect size of the gene variants identified so far in MS appears small. It is therefore important (but difficult: Sawcer and Wason, 2012) [3] to establish if and in which cases (including those gene variants with small but measurable effect size that do not reach the significance threshold of GWAS) the interaction with nonheritable factors may help understand their true impact on disease pathogenesis [4]. Furthermore, as far as the sero-epidemiological associations are concerned, their causal relevance and underlying pathogenetic mechanisms become clearer if interpreted in the light of genetic data.

As an attempt to consider, beyond the statistical paradigms of GWAS analysis, which gene-environment interactions may associate with the development of MS, we performed an interrogation of GWAS data [1] through a “candidate interactome” approach, investigating statistical enrichment of associations in genes whose products “interact” with putative environmental risk factors in MS.

We elected to center the analysis on viral interactomes, based on the classical hypothesis of a viral etiology of MS. Importantly, we examined only direct interactions between viral and human proteins as it has recently been shown that these are the interactions that are more likely to be of primary importance for the phenotypic impact of a virus in “virally implicated diseases” [5]. The chosen interactomes reflect the compromise between informative size and potential relevance for MS. In detail, EBV was chosen as main association to be verified against phylogenetically related or unrelated viruses. Given the profound influence of EBV on the immune response, and the preponderance of (auto)immune-mediated mechanisms in the pathogenesis of the disease, we added two interactomes of immunological relevance, human innate immunity interactome for type I interferon (hu-IFN) and autoimmune regulator (AIRE). Finally, we included the vitamin D receptor (VDR) and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) interactomes to evaluate, on the same grounds, also part of the molecular interactions that compose other established or emerging “environmental” associations.

Methods

Seven interactomes were obtained from the literature: EBV [6], Human Immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [7], Hepatitis C virus (HCV) [8], AIRE [9], hu-IFN [10], Influenza A virus (H1N1) [11], Virus Open Reading Frame (VIRORF) [12]. Four interactomes were manually curated: Human Herpesvirus 8 (HHV8), Cytomegalovirus (CMV), JC virus (JCV), Hepatitis B virus (HBV). VDR and AHR interactomes were extracted from BIOGRID (http: //thebiogrid.org) [13].

As reference to gather gene and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) details from their HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) Ids and rsids, we employed a local copy of the Ensembl Human databases (version 66, databases core and variation, including SNPs coming from the 1000 Genome project); the annotation adopted for the whole analysis was GRCh37-p6, that includes the release 6 patches (Genome Reference Consortium: human assembly data - GRCh37.p6 - Genome Assembly. http: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/assembly/304538/).

The genotypic p-values of association for each tested SNP were obtained from the International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium & Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium,2 study. All SNPs which did not pass quality checks in the International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium & the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium,2 study were filtered out from the original data. We used ALIGATOR [14], [15] to evaluate how single genes get summed to provide total contribution of candidate interactomes (Table S1). The idea behind ALIGATOR’s strategy is to evaluate gene category significance by means of an empirical approach, comparing each interactome with the null hypothesis, built using random permutations of the data. Such method begins its analyses by evaluating the Gene Ontology (GO) category association in each interactome provided: (i) each SNP with a p-value stronger than the P-CUT parameter is associated to the gene within 20 kb; then the most representative SNP for each gene is selected; (ii) LD filter of SNPs that have an r2≤0.2 and those that are farther than 1000 kb; (iii) count the number of genes significant in each GO category. This is the real observed data.

A non parametric bootstrap approach was used to generate a null hypothesis as follows: (i) build 5000 random interactomes (of the same size of the one under analysis, this procedure is repeated for each interactome); (ii) obtain category-specific p-values by comparing each random interactome with the remaining 4999 built; (iii) elect one of the interactomes in (i) as simulated observed data; (iv) randomly sample interactomes in (i) to generate category-specific p-values; (v) repeat (iv) to simulate 1000 simulated studies. The GO category association distribution in the real observed data is then compared with the null hypothesis: (i) generate an expected number of significant genes in each category, using the simulated studies; (ii) compare the number of significant categories in the real observed data with (i). ALIGATOR parameters that we used are those of its reference paper [14]. p-value cut-off was taken at 0.05, only the SNPs with marginal p-value less than this cut-off were employed (p-value cut-offs were also taken at 0.005 and 0.03 for the re-analysis of interactomes that resulted associated at 0.05, see results). Furthermore, to limit the uncertainties introduced by combined SNP effects in the MHC extended region (that is the haplotype set with the strongest signal in our analysis), we computed two different statistical evaluations for each interactome, one including and the other one excluding SNPs coming from such region (we considered as belonging to the extended MHC region all those SNPs that participate in at least one of the following haplotypes: HSCHR6_MHC_APD, HSCHR6_MHC_COX, HSCHR6_MHC_DBB, HSCHR6_MHC_MANN, HSCHR6_MHC_MCF, HSCHR6_MHC_QBL, HSCHR6_MHC_SSTO according to GRC data). In both cases we used Ensembl API [16] and BioPerl [17] (version 1.2.3) to gather all SNP information, haplotype participation, genes position and size [18]; such annotated information was then fed into ALIGATOR together with the interactomes.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) was employed twice: (i) before the ALIGATOR statistics, to characterize the composition of our interactomes (Table S2), and (ii) on the genes with nominally significant evidence of association [1] that ALIGATOR took as representative of each interactome-SNP relation (Table S3). In both cases we performed the IPA-”core analysis”, and we restricted the settings to show only molecular and functional associations. Afterwards, we used IPA-”comparative analysis” to produce the p-value of association between each functional class and all our interactomes. IPA knowledge base (ie, the input data used by IPA) was set to the following criteria in every analyses: consider only molecules and/or relationships where the species in object was human (or it was a chemical), and the datum was experimentally observed. Since IPA-”comparative analysis” provides p-value ranges associated to functional classes, we took as reference the value used by IPA to fill its reports, namely the best p-value for that class.

Results

We performed a “candidate interactome” (i.e. a group of genes whose products are known to physically interact with environmental factors that may be relevant for disease pathogenesis) analysis of genome-wide association data in multiple sclerosis.

We obtained 13 interactomes, 7 from the literature (as such) and 6 by manually selecting those interactions that were reported by two independent sources or were confirmed by the same source with distinct experimental approaches. In all cases we considered only physical-direct interactions (Table S2,Table 1).

Table 1. Statistical enrichment of MS-associated genes within each interactome.

| Interactome | Size | Source | p-value with MHC | p-value without MHC |

| VIRORF | 579 | Experimental data [12] | 0.0610 | 0.0632 |

| HIV | 446 | Experimental data [7] | 0.0026 | 0.0034 |

| HCV | 202 | Experimental data [8] | 0.4244 | 0.4424 |

| hu-IFN | 113 | Experimental data [10] | 0.2176 | 0.1838 |

| EBV | 110 | Experimental data [6] | 0.0140 | 0.0446 |

| H1N1 | 87 | Experimental data [11] | 0.9572 | 0.9648 |

| AIRE | 45 | Experimental data [9] | 0.4322 | 0.4012 |

| HBV | 85 | manually curated | 0.0124 | 0.0236 |

| CMV | 41 | manually curated | 0.1156 | 0.3322 |

| HHV8 | 40 | manually curated | 0.1132 | 0.0920 |

| JCV | 10 | manually curated | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| VDR | 78 | BioGRID | 0.1848 | 0.1802 |

| AHR | 30 | BioGRID | 0.8752 | 0.8522 |

ALIGATOR-obtained interactome p-values (overall contribution given by SNP p-values to each interactome, with and without SNPs falling in the MHC region). The SNPs with marginal p-value less than 0.05 were employed.

MS = multiple sclerosis; ALIGATOR = Association LIst Go AnnoTatOR; SNP = single nucleotide polymorphism; MHC = Major histocompatibility complex; BioGRID = Biological General Repository for Interaction Datasets; VIRORF = Virus Open Reading Frame; HIV = Human Immunodeficiency virus; HCV = Hepatitis C virus; hu-IFN = human innate immunity interactome for type I interferon; EBV = Epstein Barr virus; H1N1 = Influenza A virus; HBV = Hepatitis B virus; VDR = vitamin D receptor; AIRE = autoimmune regulator; CMV = Cytomegalovirus; HHV8 = Human Herpesvirus 8; JCV = JC virus; AHR = Aryl hydrocarbon receptor.

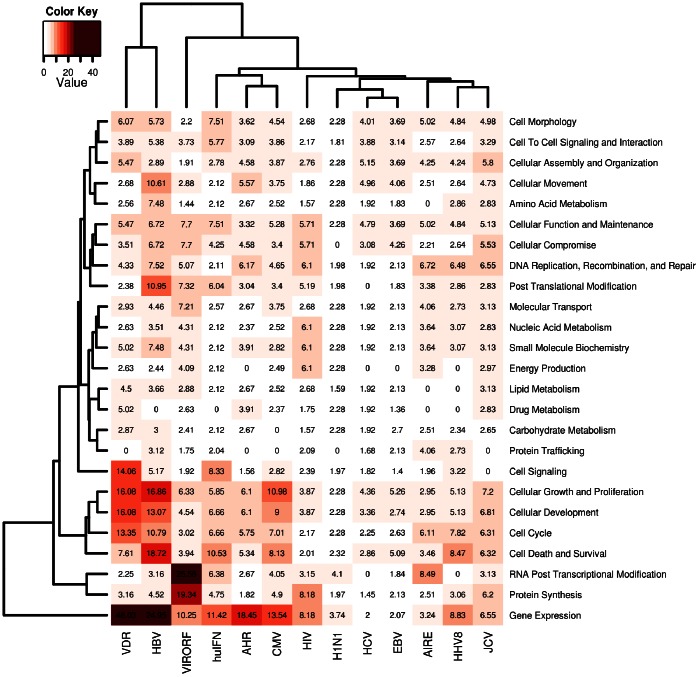

Preliminarily to the enrichment of association analysis, we used IPA to obtain a sense of the cellular signaling pathways that are targeted by each interactome. A classification for molecular and cellular functions showed a comparable distribution of components in most interactomes except for VDR, HBV, VIRORF and hu-IFN where a relative enrichment of some functional pathways (cell signaling, cellular growth and proliferation, cellular development, cell cycle, cell death and survival, protein synthesis, RNA post-transcriptional modification, gene expression) was present (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Heatmap from Ingenuity Pathway Analysis of each interactome.

Statistical significance (in –log[p-value] notation, where p<0.05 corresponds to a –log[p]>1.3) of the functional components in each interactome, as obtained through a Comparative Core-Analysis in IPA (Ingenuity Pathway Analysis). The functional components identified at the molecular and cellular level are presented row-wise (right); the interactomes are presented column-wise (bottom). Each cell in position (i,j) contains a number that represents in −log notation the strength of the association between the functional class i and the interactome j; this information is also color-matched with a color gradient that moves from white (−log[p] = 0.0, p = 1) to crimson (−log[p] = 50, p<10−50). Two hierarchical cluster analyses were employed to group functional classes that share similar patterns of associations across all interactomes (left-side clustering), and to group interactomes that share similar functional compositions (top-chart clustering).

We investigated statistical enrichment of associations within each one of the above interactomes (Table 1). The analyses were performed with and without considering SNPs falling in the MHC extended region. In both cases the interactomes of EBV, HIV and HBV reached significance. To verify the sensitivity of our results with respect to a choice (SNPs p-value cut-off at 0.05) that is not obvious based on the literature published so far, we evaluated different cut-offs (p<0.005 and p<0.03) on the three interactomes that were MS-associated at p<0.05. These analyses supported the consistency of the results (Table S4).

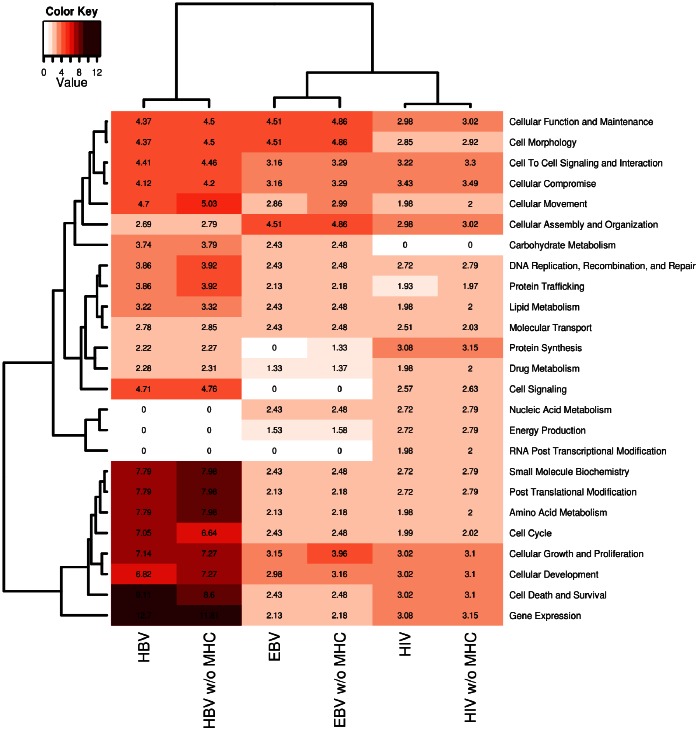

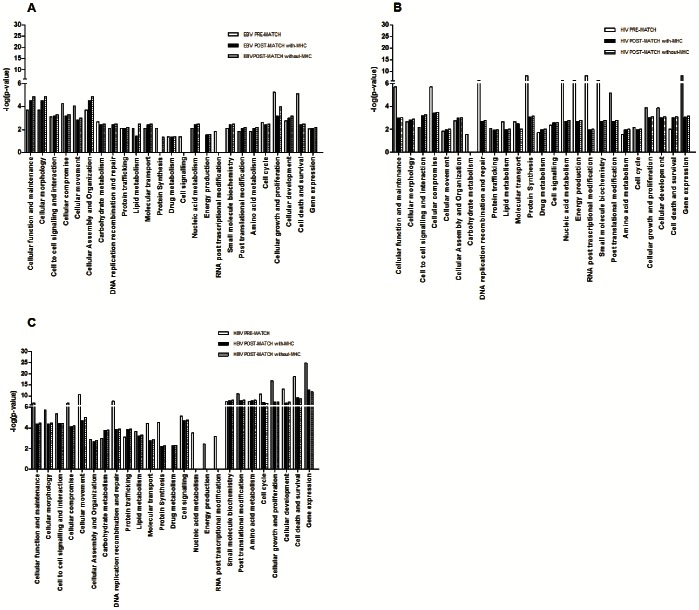

We then performed the same IPA classification as in Figure 1 (Figure 2) on the MS-associated genes within the EBV, HIV and HBV interactomes (Table S3). The aim was to verify whether the associations emerging from the three interactomes implied new and MS-specific perturbations and whether these perturbations are virus-specific or shared by the three pathogens. The comparison between pre- and post-match distribution of the functional classes (Figure 3) showed that the MS-associated interactomes did not reflect a clear cut involvement of specific pathways though, in the case of EBV, an enrichment of some biological functions (cellular function and maintenance, cell morphology, cellular assembly and organization, energy production) was present. On the other hand the most frequent changes for HBV and HIV could be in accord with the post-match reduction of the interactome sizes.

Figure 2. Heatmap from Ingenuity Pathway Analysis of MS-associated interactomes.

Statistical significance (in –log[p-value] notation, where p<0.05 corresponds to a –log[p]>1.3) of the functional components in each one of the three MS-associated interactomes (Table S3) computed by ALIGATOR (Association LIst Go AnnoTatOR) first flow process. These p-values were obtained through a Comparative Core-Analysis in IPA (Ingenuity Pathway Analysis). The functional components identified at the molecular and cellular level are presented row-wise; the interactome sub-sets are presented column-wise. Each cell in position (i,j) contains a number that represents in −log notation the strength of the association between the functional class i and the interactome; this information is also color-matched with a color gradient that moves from white (−log[p] = 0.0, p = 1) to crimson (−log[p] = 14, p<10−14). Two hierarchical cluster analyses were employed to group functional classes that share similar patterns of associations across all interactome sub-sets (left-side clustering), and to group interactome sub-sets that share similar functional compositions (top-chart clustering).

Figure 3. Histograms of functional class distribution of MS-associated interactomes.

The histograms show the strength of the association between each IPA functional class and the 3 MS-associated interactomes (EBV [A], HIV [B] and HBV [C]). For each functional class 3 values were derived according to its distribution before (Figure 1) and after (Figure 2, with and without MHC [Major histocompatibility complex]) the ALIGATOR (Association LIst Go AnnoTatOR) statistical analysis of association.

Discussion

Of the 13 interactomes, 3 show a statistical enrichment of associations. In line with the epidemiological and immunological literature, the EBV interactome is among these. The lack of significant associations with the hu-IFN and AIRE interactomes suggests, though does not exclude, that the result is not an effect of the immunological connotation of the EBV interactome. The absence of associations with the interactomes of phylogenetically related viruses (CMV and HHV8, both herpesviruses with the latter that shares the same site of latency as EBV and belongs to the same subfamily of gamma-herpesviridae) reinforces the specificity of the EBV result. The fact that a portion of the genetic predisposition to MS may be attributable to variants in genes that interact with EBV may be complementary to another our finding showing that EBV genomic variants significantly associate with MS (unpublished data): the two results suggest a model of genetic jigsaw puzzle, whereby both host and virus polymorphisms affect MS susceptibility and, through complex epistatic interactions, eventually lead to disease development.

The associations with the HBV and HIV interactomes were unexpected. Overall, epidemiological data do not support a role of these viruses in the pathogenesis of MS though some controversy still holds concerning the safety of HBV vaccination [19]–[23]. Interestingly, Gregory et al. (2012) [24] demonstrated that in the TNFRSF1A gene, which is part of the HBV interactome, the MS-associated variant directs increased expression of a soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1.

Concerning HIV, the lack of epidemiological association seems more established. However, demyelination is a feature of HIV encephalomyelopathy [25] and cases of difficult differential diagnoses or association between the two conditions are described in the literature [26], [27]. All this considered, it might not be surprising that some molecular interactions that take place between HIV and host may predispose to demyelination. Other viruses, sharing homology with HIV may possess better paraphernalia and be more prone to cause MS. The HERV-W family has long been associated with MS [28] and HERV-W/Env, whose expression is associated with MS [29], is able to complement an env-defective HIV strain [30] suggesting a certain degree of functional kinship.

Apart from any conjectures about the data on HBV and HIV interactomes, it remains true, as recently demonstrated by Pichlmair and colleagues (2012) [12], that viruses use unique but also common strategies to perturb the human molecular network. Our pathway analyses do not suggest, in fact, any specific cellular signaling target for the three viruses in MS, perhaps with some exceptions as far as the EBV interactome is concerned. Though preliminary, this acquisition may be in accord with the largely accepted view that, alongside the risk associated with EBV infection, there can be a more general risk of developing MS linked to a variety of other infections [31], [32].

The VDR interactome does not show significant enrichment of associations. The result does by no means diminishes the importance of the epidemiological association between vitamin D and MS: its causal relevance is already supported by data that are starting to explain the molecular basis of this association, upstream [33]–[35], [1] and downstream the interactions between the VDR and its protein cofactors [36], [37].

Current approaches for gene set analysis are in their early stage of development and there are still potential sources of bias or discrepancy among different methods, including those used in our study. As the reproducibility of the techniques increases, and new facilities [38] and methods become available to identify interactions that still escape detection, new lists will become available for matching with GWAS data. In parallel, also the assessment of human genetic variation will become more comprehensive [39]. Hence, the “candidate interactome” approach may become an increasingly meaningful strategy to interpret genetic data in the light of acquisitions from epidemiology and pathophysiology. Notably, this approach appears to be complementary to other studies, which look for statistical enrichment of associations in an unbiased way, and may disclose unexpected pathways in MS susceptibility [40].

At present, our results support a causal role of the interaction between EBV and the products of MS-associated gene variants. Other viruses may be involved, through common and unique mechanisms of molecular perturbation.

Supporting Information

ALIGATOR settings.

(XLS)

Composition of all the interactomes. Lists of genes of each interactome as obtained from the literature. VIRORF = Virus Open Reading Frame; HIV = Human Immunodeficiency virus; HCV = Hepatitis C virus; hu-IFN = human innate immunity interactome for type I interferon; EBV = Epstein Barr virus; H1N1 = Influenza A virus; HBV = Hepatitis B virus; VDR = vitamin D receptor; AIRE = autoimmune regulator; CMV = Cytomegalovirus; HHV8 = Human Herpesvirus 8; JCV = JC virus; AHR = Aryl hydrocarbon receptor.

(DOC)

List of genes within molecular and functional classes in the three MS-associated interactomes (p-value cut-off<0.05). MS = multiple sclerosis; HIV = Human Immunodeficiency virus; EBV = Epstein Barr virus; HBV = Hepatitis B virus; MHC = Major histocompatibility complex

(XLS)

Statistical enrichment of MS-associated interactomes (p-value cut-off<0.005; 0.03). ALIGATOR-obtained interactome p-values (overall contribution given by SNP p-values to each interactome, with and without SNPs falling in the MHC region). MS = multiple sclerosis; ALIGATOR = Association LIst Go AnnoTatOR; SNP = single nucleotide polymorphism; MHC = Major histocompatibility complex; HIV = Human Immunodeficiency virus; EBV = Epstein Barr virus; HBV = Hepatitis B virus.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Eliana Coccia (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy) for her helpful contribution to obtain the interactomes.

The members of the International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium (IMSGC) and Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium,2 (WTCCC2) are: Stephen Sawcer,1 Garrett Hellenthal,2 Matti Pirinen,2 Chris C.A. Spencer,2,* Nikolaos A. Patsopoulos,3,5 Loukas Moutsianas,6 Alexander Dilthey,6 Zhan Su,2 Colin Freeman,2 Sarah E. Hunt,7 Sarah Edkins,7Emma Gray,7 David R. Booth,8 Simon C. Potter,7 An Goris,9 Gavin Band,2 Annette Bang Oturai,10 Amy Strange,2 Janna Saarela,11 Céline Bellenguez,2 Bertrand Fontaine,12 Matthew Gillman,7 Bernhard Hemmer,13 Rhian Gwilliam,7 Frauke Zipp,14,15 Alagurevathi Jayakumar,7 Roland Martin,16 Stephen Leslie,17 Stanley Hawkins,18 Eleni Giannoulatou,2 Sandra D’alfonso,19 Hannah Blackburn,7 Filippo Martinelli Boneschi,20 Jennifer Liddle,7 Hanne F. Harbo,21,22 Marc L. Perez,7Anne Spurkland,23 Matthew J Waller,7 Marcin P. Mycko,24 Michelle Ricketts,7 Manuel Comabella,25 Naomi Hammond,7Ingrid Kockum,26 Owen T. McCann,7 Maria Ban,1 Pamela Whittaker,7 Anu Kemppinen,1 Paul Weston,7 Clive Hawkins,27Sara Widaa,7 John Zajicek,28 Serge Dronov,7 Neil Robertson,29 Suzannah J. Bumpstead,7 Lisa F. Barcellos,30,31 Rathi Ravindrarajah,7 Roby Abraham,27 Lars Alfredsson,32 Kristin Ardlie,4 Cristin Aubin,4 Amie Baker,1 Katharine Baker,29Sergio E. Baranzini,33 Laura Bergamaschi,19 Roberto Bergamaschi,34 Allan Bernstein,31 Achim Berthele,13 Mike Boggild,35 Jonathan P. Bradfield,36 David Brassat,37 Simon A. Broadley,38 Dorothea Buck,13 Helmut Butzkueven,39,42Ruggero Capra,43 William M. Carroll,44 Paola Cavalla,45 Elisabeth G. Celius,21 Sabine Cepok,13 Rosetta Chiavacci,36Françoise Clerget-Darpoux,46 Katleen Clysters,9 Giancarlo Comi,20 Mark Cossburn,29 Isabelle Cournu-Rebeix,12 Mathew B. Cox,47 Wendy Cozen,48 Bruce A.C. Cree,33 Anne H. Cross,49 Daniele Cusi,50 Mark J. Daly,4,51,52 Emma Davis,53Paul I.W. de Bakker,3,4,54,55 Marc Debouverie,56 Marie Beatrice D’hooghe,57 Katherine Dixon,53 Rita Dobosi,9 Bénédicte Dubois,9 David Ellinghaus,58 Irina Elovaara,59,60 Federica Esposito,20 Claire Fontenille,12 Simon Foote,61 Andre Franke,58 Daniela Galimberti,62 Angelo Ghezzi,63 Joseph Glessner,36 Refujia Gomez,33 Olivier Gout,64 Colin Graham,65Struan F.A. Grant,36,66,67 Franca Rosa Guerini,68 Hakon Hakonarson,36,66,67 Per Hall,69 Anders Hamsten,70 Hans-Peter Hartung,71 Rob N. Heard,8 Simon Heath,72 Jeremy Hobart,28 Muna Hoshi,13 Carmen Infante-Duarte,73 Gillian Ingram,29Wendy Ingram,28 Talat Islam,48 Maja Jagodic,26 Michael Kabesch,74 Allan G. Kermode,44 Trevor J. Kilpatrick,39,40,75Cecilia Kim,36 Norman Klopp,76 Keijo Koivisto,77 Malin Larsson,70 Mark Lathrop,72 Jeannette S. Lechner-Scott,47,78Maurizio A. Leone,79 Virpi Leppä,11,80 Ulrika Liljedahl,81 Izaura Lima Bomfim,26 Robin R. Lincoln,33 Jenny Link,26Jianjun Liu,82 Åslaug R. Lorentzen,22,83 Sara Lupoli,50,84 Fabio Macciardi,50,85 Thomas Mack,48 Mark Marriott,39,40Vittorio Martinelli,20 Deborah Mason,86 Jacob L. McCauley,87 Frank Mentch,36 Inger-Lise Mero,21,83 Tania Mihalova,27Xavier Montalban,25 John Mottershead,88,89 Kjell-Morten Myhr,90,91 Paola Naldi,79 William Ollier,53 Alison Page,92 Aarno Palotie,7,11,93,94 Jean Pelletier,95 Laura Piccio,49 Trevor Pickersgill,29 Fredrik Piehl,26 Susan Pobywajlo,5 Hong L. Quach,30 Patricia P. Ramsay,30 Mauri Reunanen,96 Richard Reynolds,97 John D. Rioux,98 Mariaemma Rodegher,20Sabine Roesner,16 Justin P. Rubio,39 Ina-Maria Rückert,76 Erika Salvi,50,100 Adam Santaniello,33Catherine A. Schaefer,31 Stefan Schreiber,58,101 Christian Schulze,102 Rodney J. Scott,47 Finn Sellebjerg,10 Krzysztof W. Selmaj,24David Sexton,103Ling Shen,31 Brigid Simms-Acuna,31 Sheila Skidmore,1 Patrick M.A. Sleiman,36,66 Cathrine Smestad,21 Per Soelberg Sørensen,10 Helle Bach Søndergaard,10 Jim Stankovich,61 Richard C. Strange,27 Anna-Maija Sulonen,11,80 Emilie Sundqvist,26 Ann-Christine Syvänen,81 Francesca Taddeo,100 Bruce Taylor,61Jenefer M. Blackwell,104,105 Pentti Tienari,106 Elvira Bramon,107 Ayman Tourbah,108 Matthew A. Brown,109Ewa Tronczynska,24Juan P. Casas,110 Niall Tubridy,40,111 Aiden Corvin,112 Jane Vickery,28 Janusz Jankowski,113 Pablo Villoslada,114 Hugh S. Markus,115 Kai Wang,36,66 Christopher G. Mathew,116 James Wason,117 Colin N.A. Palmer,118 H-Erich Wichmann,76,119,120 Robert Plomin,121 Ernest Willoughby,122Anna Rautanen,2 Juliane Winkelmann,13,123,124 Michael Wittig,58,125 Richard C. Trembath,116 Jacqueline Yaouanq,126 Ananth C. Viswanathan,127 Haitao Zhang,36,66 Nicholas W. Wood,128 Rebecca Zuvich,103 Panos Deloukas,7 Cordelia Langford,7 Audrey Duncanson,129 Jorge R. Oksenberg,33 Margaret A. Pericak-Vance,87 Jonathan L. Haines,103 Tomas Olsson,26 Jan Hillert,26 Adrian J. Ivinson,51,130 Philip L. De Jager,4,5,51 Leena Peltonen,7,11,80,93,94 Graeme J. Stewart,8 David A. Hafler,4,131 Stephen L. Hauser,33 Gil McVean,2 Peter Donnelly,2,6 and Alastair Compston1

1University of Cambridge, Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK

2Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics, Roosevelt Drive, Oxford, UK

3Division of Genetics, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

4Broad Institute of Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA

5Center for Neurologic Diseases, Department of Neurology, Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

6Dept Statistics, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

7Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge, UK

8Westmead Millennium Institute, University of Sydney, Australia

9Laboratory for Neuroimmunology, Section of Experimental Neurology, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

10Danish Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology, Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark

11Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland (FIMM), University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

12INSERM UMR S 975 CRICM, UPMC, Département de neurologie Pitié-Salpêtrière, AP-HP, Paris, France

13Department of Neurology, Klinikum Rechts der Isar der Technischen Universität, Munich, Germany

14Department of Neurology, University Medicine Mainz, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Mainz, Germany

15Max Delbrueck Center for Molecular Medicine, Berlin, Germany

16Institute for Neuroimmunology and Clinical MS Research (inims), Centre for Molecular Neurobiology, Hamburg, Germany

17Department of Clinical Pharmacology, University of Oxford, Old Road Campus Research Building, Oxford, UK

18Queen’s University Belfast, University Road, Belfast, Northern Ireland, UK

19Department of Medical Sciences and Interdisciplinary Research Center of Autoimmune Diseases (IRCAD), University of Eastern Piedmont, Novara, Italy

20Department of Neurology, Institute of Experimental Neurology (INSPE), Division of Neuroscience, San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy

21Department of Neurology, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway

22Department of Neurology, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

23Institute of Basal Medical Sciences, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

24Department of Neurology, Laboratory of Neuroimmunology, Medical University of Lodz, Lodz, Poland

25Clinical Neuroinmunology Unit, Multiple Sclerosis Center of Catalonia (CEM-Cat), Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain

26Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Centre for Molecular Medicine CMM, Karolinska Institutet, Karolinska Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden

27Keele University Medical School, Stoke-on-Trent, UK

28Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry, Universities of Exeter and Plymouth, Clinical Neurology Research Group, Tamar Science Park, Plymouth, UK

29Department of Neurology, University Hospital of Wales, Heath Park, Cardiff, UK

30Genetic Epidemiology and Genomics Laboratory, Division of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley, USA

31Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research, CA, USA

32Institute of Environmental Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

33Department of Neurology, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA

34Neurological Institute C. Mondino, IRCCS, Pavia, Italy

35The Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Liverpool, UK

36Center for Applied Genomics, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, USA

37INSERM U 563 et Pôle Neurosciences, Hopital Purpan, Toulouse, France

38School of Medicine, Griffith University, Australia

39Florey Neuroscience Institutes, University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

40Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Victoria, Australia,

41Box Hill Hospital, Box Hill, Australia

42Department of Medicine, RMH Cluster, University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

43Multiple Sclerosis Centre, Department of Neurology, Ospedali Civili di Brescia, Brescia, Italy

44Centre for Neuromuscular and Neurological Disorders, University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia

45Department of Neurosciences, University of Turin, A.O.U. San Giovanni Battista,Turin, Italy

46INSERM U535, Univ Paris-Sud, Villejuif, France

47University of Newcastle, University Drive, Callaghan NSW, Australia

48Department of Preventive Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

49Department of Neurology, Washington University, St Louis MO, USA

50University of Milan, Department of Medicine, Surgery and Dentistry, AO San Paolo, University of Milan, c/o Filarete Foundation - Milano, Italy

51Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

52Center for Human Genetic Research, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

53The UK DNA Banking Network, Centre for Integrated Genomic Medical Research, University of Manchester, UK

54Department of Medical Genetics, Division of Biomedical Genetics, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands

55Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands

56Service de Neurologie, Hôpital Central, Nancy, France

57National Multiple Sclerosis Center, Melsbroek, Belgium

58Institute for Clinical Molecular Biology, Christian-Albrechts-University, Kiel, Germany

59Department of Neurology, Tampere University Hospital, Tampere, Finland

60University of Tampere, Medical School, Tampere, Finland

61Menzies Research Institute, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia 62Department of Neurological Sciences, Centro Dino Ferrari, University of Milan, Fondazione Cà Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy

63Centro Studi Sclerosi Multipla, Ospedale di Gallarate, Gallarate (VA), Italy

64Service de Neurologie, Fondation Ophtalmologique Adolphe de Rothschild, Paris, France

65Belfast Health and Social Care Trust, City Hospital, Belfast, Northern Ireland,UK

66Division of Genetics, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, USA

67Department of Pediatrics, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, USA

68Laboratory of Molecular Medicine and Biotechnology, Don C. Gnocchi Foundation IRCCS, S. Maria Nascente, Milan, Italy

69Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden

70Atherosclerosis Research Unit, Department of Medicine Solna, Karolinska Institutet, Center for Molecular Medicine, Karolinska University Hospital Solna, Stockholm, Sweden

71Department of Neurology, Heinrich-Heine-University, Düsseldorf, Germany

72Centre National de Genotypage, Evry Cedex, France

73Experimental and Clinical Research Center, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and Max Delbrueck Center for Molecular Medicine, Berlin, Germany

74Clinic for Paediatric Pneumology, Allergology and Neonatology, Hannover Medical School, Germany

75Centre for Neuroscience, University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

76Institute of Epidemiology, Helmholtz Zentrum München, German Research Center for Environmental Health, Neuherberg, Munich, Germany

77Seinäjoki Central Hospital, Seinäjoki, Finland

78Hunter Medical Research Institute, John Hunter Hospital, Lookout Road, New Lambton NSW, Australia

79SCDU Neurology, Maggiore della Carità Hospital, Novara, Italy

80Unit of Public Health Genomics, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki, Finland

81Molecular Medicine, Department of Medical Sciences, Uppsala University, Entrance 70, 3rd Floor, Res Dept 2, Univeristy Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden

82Human Genetics and Cancer Biology, Genome Institute of Singapore, Singapore 83Institute of Immunology, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway

84Institute of Experimental Neurology (INSPE), San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy

85Dept of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of California, Irvine (UCI), Irvine CA, USA

86Christchurch School of Medicine, University of Otago, Christchurch, New Zealand

87John P. Hussman Institute for Human Genomics and The Dr. John T Macdonald Foundation Department of Human Genetics, University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine, Miami, USA

88Greater Manchester Centre for Clinical Neurosciences, Hope Hospital, Salford, UK

89The Department of Neurology, Dunedin Public Hospital, Otago, NZ

90The Multiple Sclerosis National Competence Centre, Department of Neurology, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway

91Department of Clinical Medicine, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway

92Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust, Department of Neurology, Derriford Hospital, Plymouth, UK

93Department of Medical Genetics, University of Helsinki and University Central Hospital, Helsinki, Finland

94Program in Medical and Population Genetics and Genetic Analysis Platform, The Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, USA

95Pôle Neurosciences Cliniques,Service de Neurologie, Hôpital de la Timone, Marseille, France

96Department Neurology, Oulu University Hospital, Oulu, Finland

97UK MS Tissue Bank, Wolfson Neuroscience Laboratories, Imperial College London, Hammersmith Hospital, London, UK

98Université de Montréal & Montreal Heart Institute, Research Center, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

100KOS Genetic Srl, Milan - Italy

101Department of General Internal Medicine, University Hospital, Schleswig-Holstein, Christian-Albrechts-University, Kiel, Germany

102Systems Biology and Protein-Protein Interaction, Center for Molecular Neurobiology, Hamburg, Germany

103Center for Human Genetics Research, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, USA

104Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, Centre for Child Health Research, University of Western Australia, Australia

105Cambridge Institute for Medical Research, University of Cambridge School of Clinical Medicine, Cambridge, UK

106Department of Neurology, Helsinki University Central Hospital and Molecular Neurology Programme, Biomedicum, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

107Division of Psychological Medicine and Psychiatry, Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at the Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London and The South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, Denmark Hill, London, UK

108Service de Neurologie et Faculté de Médecine de Reims, Université de Reims Champagne-Ardenne, Reims, France

109University of Queensland Diamantina Institute, Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, Australia

110Dept Epidemiology and Population Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK

111St. Vincent’s University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

112Neuropsychiatric Genetics Research Group, Institute of Molecular Medicine, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

113Centre for Gastroenterology, Bart’s and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, London, UK

114Department of Neurosciences, Institute of Biomedical Research August Pi Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

115Clinical Neurosciences, St George’s University of London, London, UK

116Dept Medical and Molecular Genetics, King’s College London School of Medicine, Guy’s Hospital, London, UK

117Medical Research Council Biostatistics Unit, Robinson Way, Cambridge, UK

118Biomedical Research Institute, University of Dundee, Ninewells Hospital and Medical School, Dundee, UK

119Institute of Medical Informatics, Biometry and Epidemiology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich, Germany

120Klinikum Grosshadern, Munich, Germany

121King’s College London, Social, Genetic and Developmental Psychiatry Centre, Institute of Psychiatry, Denmark Hill, London, UK

122Department of Neurology, Auckland City Hospital, Grafton Road, Auckland, New Zealand

123Institut für Humangenetik, Technische Universität München, Germany

124Institut für Humangenetik, Helmholtz Zentrum München, Germany

125Popgen Biobank, Christian-Albrechts University Kiel, Kiel, Germany

126Pôle Recherche et Santé Publique, CHU Pontchaillou, Rennes, France

127NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Ophthalmology, Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, London, UK

128Dept Molecular Neuroscience, Institute of Neurology, Queen Square, London, UK

129Molecular and Physiological Sciences, The Wellcome Trust, London, UK

130Harvard NeuroDiscovery Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

131Department of Neurology & Immunology, Yale University Medical School, New Haven, CT, USA

Funding Statement

This work was funded by Italian Multiple Sclerosis Foundation grants (2007/R/17 and 2011/R/31) to MS. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium & Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium,2 (2011) Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature 476: 214–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kakalacheva K, Lünemann JD (2011) Environmental triggers of multiple sclerosis. FEBS Lett 585: 3724–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sawcer S, Wason J (2012) Risk in complex genetics: “All models are wrong but some are useful”. Ann Neurol 72: 502–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Visscher PM, Hill WG, Wray NR (2008) Heritability in the genomics era - concepts and misconceptions. Nat Rev Genet 9: 255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gulbahce N, Yan H, Dricot A, Padi M, Byrdsong D, et al. (2012) Viral perturbations of host networks reflect disease etiology. PLoS Comput Biol 8: e1002531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Calderwood MA, Venkatesan K, Xing L, Chase MR, Vazquez A, et al. (2007) Epstein-Barr virus and virus human protein interaction maps. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 7606–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jäger S, Cimermancic P, Gulbahce N, Johnson JR, McGovern KE, et al. (2011) Global landscape of HIV-human protein complexes. Nature 481: 365–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Chassey B, Navratil V, Tafforeau L, Hiet MS, Aublin-Gex A, et al. (2008) Hepatitis C virus infection protein network. Mol Syst Biol. 4: 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abramson J, Giraud M, Benoist C, Mathis D (2010) AIRE’s partners in the molecular control of immunological tolerance. Cell 140: 123–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li S, Wang L, Berman M, Kong YY, Dorf ME (2011) Mapping a dynamic innate immunity protein interaction. Immunity 35: 426–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shapira SD, Gat-Viks I, Shum BO, Dricot A, de Grace MM, et al. (2009) A physical and regulatory map of host-influenza interactions reveals pathways in H1N1 infection. Cell. 139: 1255–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pichlmair A, Kandasamy K, Alvisi G, Mulhern G, Sacco R, et al. (2012) Viral immune modulators perturb the human molecular network by common and unique strategies. Nature 487: 486–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stark C, Breitkreutz BJ, Chatr-Aryamontri A, Boucher L, Oughtred R, et al. (2011) The BioGRID Interaction Database: 2011 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 39: D698–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Holmans P, Green EK, Pahwa JS, Ferreira MA, Purcell SM, et al. (2009) Gene ontology analysis of GWA study data sets provides insights into the biology of bipolar disorder. Am J Hum Genet 85: 13–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Houlston RS, Cheadle J, Dobbins SE, Tenesa A, Jones AM, et al. (2010) Meta-analysis of three genome-wide association studies identifies susceptibility loci for colorectal cancer at 1q41, 3q26.2, 12q13.13 and 20q13.33. Nat Genet 42: 973–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rios D, McLaren WM, Chen Y, Birney E, Stabenau A, et al. (2010) A database and API for variation, dense genotyping and resequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics 11: 238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stajich JE (2007) An Introduction to BioPerl. Methods Mol Biol 406: 535–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pesole G (2008) What is a gene? An updated operational definition. Gene 417: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Confavreux C, Suissa S, Saddler P, Bourdès V, Vukusic S (2001) Vaccines in multiple sclerosis study group. Vaccinations and risk of relapses in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 344: 319–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ascherio A, Zhang SM, Heman MA, Olek MJ, Coplan PM, et al. (2001) Hepatitis B vaccination and the risk of multiple sclerosis N Engl J Med. 344: 327–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hernán MA, Jick SS, Olek MJ, Jick H (2004) Recombinant hepatitis B vaccine and the risk of multiple sclerosis: a prospective study. Neurology 63: 838–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mikaeloff Y, Caridade G, Suissa S, Tardieu M (2009) Hepatitis B vaccine and the risk of CNS inflammatory demyelination in childhood. Neurology 72: 873–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Loebermann M, Winkelmann A, Hartung HP, Hengel H, Reisinger EC, et al. (2012) Vaccination against infection in patients with multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 8: 143–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gregory AP, Dendrou CA, Attfield KE, Haghikia A, Xifara DK, et al. (2012) TNF receptor 1 genetic risk mirrors outcome of anti-TNF therapy in multiple sclerosis. Nature 488: 508–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnson RT (1994) The virology of demyelinating diseases. Ann Neurol 36 Suppl: S54–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Berger JR, Sheremata WA, Resnick L, Atherton S, Fletcher MA, et al. (1989) Multiple sclerosis-like illness occurring with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Neurology 39: 324–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. González-Duarte A, Ramirez C, Pinales R, Sierra-Madero J (2011) Multiple sclerosis typical clinical and MRI findings in a patient with HIV infection. J Neurovirol 17: 504–08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Perron H, Garson JA, Bedin F, Beseme F, Paranhos-Baccala G, et al. (1997) Molecular identification of a novel retrovirus repeatedly isolated from patients with multiple sclerosis. The Collaborative Research Group on Multiple Sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 7583–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perron H, Germi R, Bernard C, Garcia-Montojo M, Deluen C, et al.. (2012) Human endogenous retrovirus type W envelope expression in blood and brain cells provides new insights into multiple sclerosis disease. Mult Scler Mar 30 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30. An DS, Xie YM, Chen IS (2001) Envelope gene of the human endogenous retrovirus HERV-W encodes a functional retrovirus envelope. J Virol 75: 3488–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ristori G, Cannoni S, Stazi MA, Vanacore N, Cotichini R, et al. (2006) Multiple sclerosis in twins from continental Italy and Sardinia: a nationwide study. Ann Neurol 59: 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ascherio A, Munger KL (2007) Environmental risk factors for multiple sclerosis. Part I: the role of infection. Ann Neurol 61: 288–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Torkildsen O, Knappskog PM, Nyland HI, Myhr KM (2008) Vitamin D-dependent rickets as a possible risk factor for multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 65: 809–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Australia and New Zealand Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium (ANZgene) (2009) Genome-wide association study identifies new multiple sclerosis susceptibility loci on chromosomes 12 and 20. Nat Genet 41: 824–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ramagopalan SV, Dyment DA, Calder MZ, Morrison KM, Disanto G, et al. (2011) Rare variants in the CYP27B1 gene are associated with multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 70: 881–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ramagopalan SV, Heger A, Berlanga AJ, Maugeri NJ, Lincoln MR, et al. (2010) A ChIP-seq defined genome-wide map of vitamin D receptor binding: associations with disease and evolution. Genome Res 20: 1352–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Disanto G, Sandve GK, Berlanga-Taylor AJ, Ragnedda G, Morahan JM, et al. (2012) Vitamin D receptor binding, chromatin states and association with multiple sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 21: 3575–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Orozco LD, Bennett BJ, Farber CR, Ghazalpour A, Pan C, et al. (2012) Unraveling inflammatory responses using systems genetics and gene-environment interactions in macrophages. Cell 151: 658–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ecker JR, Bickmore WA, Barroso I, Pritchard JK, Gilad Y, et al. (2012) Genomics: ENCODE explained. Nature 489: 52–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Baranzini SE, Galwey NW, Wang J, Khankhanian P, Lindberg R, et al. (2009) Pathway and network-based analysis of genome-wide association studies in multiple sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 18: 2078–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ALIGATOR settings.

(XLS)

Composition of all the interactomes. Lists of genes of each interactome as obtained from the literature. VIRORF = Virus Open Reading Frame; HIV = Human Immunodeficiency virus; HCV = Hepatitis C virus; hu-IFN = human innate immunity interactome for type I interferon; EBV = Epstein Barr virus; H1N1 = Influenza A virus; HBV = Hepatitis B virus; VDR = vitamin D receptor; AIRE = autoimmune regulator; CMV = Cytomegalovirus; HHV8 = Human Herpesvirus 8; JCV = JC virus; AHR = Aryl hydrocarbon receptor.

(DOC)

List of genes within molecular and functional classes in the three MS-associated interactomes (p-value cut-off<0.05). MS = multiple sclerosis; HIV = Human Immunodeficiency virus; EBV = Epstein Barr virus; HBV = Hepatitis B virus; MHC = Major histocompatibility complex

(XLS)

Statistical enrichment of MS-associated interactomes (p-value cut-off<0.005; 0.03). ALIGATOR-obtained interactome p-values (overall contribution given by SNP p-values to each interactome, with and without SNPs falling in the MHC region). MS = multiple sclerosis; ALIGATOR = Association LIst Go AnnoTatOR; SNP = single nucleotide polymorphism; MHC = Major histocompatibility complex; HIV = Human Immunodeficiency virus; EBV = Epstein Barr virus; HBV = Hepatitis B virus.

(DOC)