Abstract

Background

Residents of long-term care facilities (LTCFs) are a population vulnerable to infections and to the adverse effects of inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing. To improve the care of residents with possible infections, we initiated a LTCF Infectious Disease (LID) service that provides on-site consultations to LTCF residents.

Design

Clinical demonstration project

Setting

A 160-bed LTCF affiliated with a tertiary care Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital.

Participants

Residents referred to the LID Team.

Measurements

The reason for and source of LTCF residents’ referral to the LID team as well as their demographics, infectious disease diagnoses, interventions and hospitalizations were determined.

Results

Between July 2009 and December 2010, the LID consult service provided 291 consults for 250 LTCF residents. Referrals came from either the LTCF staff (75%) or the VA hospital’s ID consult service (25%). The most common diagnoses were Clostridium difficile infection (14%), asymptomatic bacteriuria (10%), and urinary tract infection (10%). More than half of referred patients were on antibiotic therapy when first seen by the LID team; 46% of patients required an intervention. The most common interventions, stopping (32%) or starting (26%) antibiotics, were made in accordance with principles of antibiotic stewardship.

Conclusion

The LID team represents a novel and effective means to bring subspecialty care to LTCF residents.

Keywords: Long-term care facility/nursing home, infectious diseases, antimicrobial stewardship, older adults

Introduction

By the year 2030, 70 million people in the United States will be at least 65 years of age [1]. Given that 3.6% of people older than 65 are nursing home residents [2], the need for long-term care facility beds (LTCF) will rise [1]. Furthermore, the complexity of medical care among these individuals, both in terms of the need for assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs) and the use of invasive medical devices, is also climbing [2-4]. Finally, LTCF residents experience frequent transfers to and from acute care institutions, which in turn increases their exposure to and acquisition of nosocomial pathogens such as Clostridium difficile, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and other multi-drug resistant organisms (MDROs) [5].

Diagnosing and treating infections among LTCF residents presents challenges even to experienced practitioners. The vast majority (85%) of clinicians who serve LTCFs are community-based physicians with training in family or internal medicine but not geriatrics [2,6]. These providers may lack expertise to address complicated infections like osteomyelitis, endocarditis, HIV/AIDS or those caused by MDROs. Furthermore, they must often rely on clinical information gathered by LTCF staff who are not trained to evaluate patients with a possible infection [7]. Additional constraints for LTCF practitioners include difficulty with access to and accuracy of residents’ medical records, poor nursing and clinical support, and a lack of time and reimbursement [6]. Together, these challenges generate an environment in which busy practitioners address potential infections by relying on brief communiqués from the LTCF staff. This results in a “treat-first” response, contributing to the estimated 25-75% inappropriate antimicrobial prescriptions at LTCFs [9,10].

At our large urban Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital the affiliated LTCF, known as a Community Living Center (CLC), also faced difficulties related to diagnosis and treatment of residents with infectious diseases. A randomized chart review of antibiotics initiated at the CLC revealed that 43% of antibiotic days of therapy were unnecessary [11]. Furthermore, patients discharged from the hospital to the CLC on long-term parental intravenous antimicrobials often suffered from poor continuity of care. To improve the care of CLC residents with concerns related to infectious diseases, we developed a LTCF ID consult (LID) team specifically designed to bring ID expertise to the CLC. We describe the LID team’s practice, including the duration, frequency and reason for consultations as well as the interventions made by the LID service. New consultations came from both the CLC staff and the hospital ID consult service. Based on our previous data indicating unnecessary antimicrobial prescriptions for CLC residents, we anticipated that residents referred by the CLC staff would require more interventions. To assess this, we specifically compare the referrals originating from the CLC staff vs. the hospital ID service.

Methods

Setting

The VA CLC contained 160 beds divided among 4 wards, each of which was staffed by a nurse practitioner or physician assistant; two physicians oversaw two wards each. Three of the 4 wards included a mix of residents who required skilled care, intermediate care or custodial care (average length of stay (LOS), 54.6 days); the 4th was a secured dementia unit (average LOS, 73.7 days). Each ward had common dining, recreation, bathroom and bathing facilities.

Intervention

The LID Consult Service consisted of an Infectious Disease physician (MD) and nurse practitioner (NP) that rounded once weekly and were available by phone or pager the remainder of the week. The LID team saw patients referred by the hospital ID service or by the CLC staff via phone, personal communication or the electronic medical record. The CLC staff was not obligated to involve the LID team for routine antimicrobial prescriptions. The LID team MD and/or NP saw residents in their rooms at the CLC. Recommendations by the LID providers were communicated via the electronic medical record and, whenever possible, also through direct communication with the primary team. When appropriate, the LID team placed orders pertaining to antibiotics and related medications as well as diagnostic studies and laboratory requests.

Outcomes

CLC residents seen in consultation during the first 18 months of the LID service (July 2009 – December 2010) were entered into a database. Using chart review, we collected the following information regarding characteristics of the CLC residents: age, gender, ethnicity, death within 1 year of the study period and age at death; laboratory values within 7 days of the first consult (white blood cell count, hemoglobin, creatinine, albumin) and the Braden score within 7 days before or 30 days following the first consult [12]. We also evaluated characteristics of the consultations: referred by the CLC staff or the hosptial ID consult service, consult-related diagnoses, whether the patient was on antibiotics at the first LID team visit, the number of days each patient was followed, the total number of notes per consult, follow-up in the outpatient ID clinic following discharge from the CLC, referrals for hospice care and hospital transfers. Finally, we also determined the nature of the LID service’s interventions: starting or stopping antibiotics, deescalation, decreasing the length of therapy, changing the therapy due to a contraindication, dose adjustment and recommendations to evaluate and treat a non-infectious condition.

Analysis

Parameters were analyzed using R (version 2.14.2; Vienna, Austria) [13]. Differences between residents referred by the CLC staff vs. the hospital ID consult service were determined using the Chi-square test for nominal data and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for continuous data. Bonferroni’s correction was applied when multiple comparisons were made. Multivariate analyses using logistic regression were conducted to analyze the relationship between referral source and the likelihood of hospital transfer or LID team intervention recommendation. For both outcomes, the control variables were patient age, race or ethnicity, laboratory values, Braden score, and the 5 most common diagnoses. The hospital transfer model included whether an intervention was needed and the intervention model included whether a hospital transfer occurred.

Results

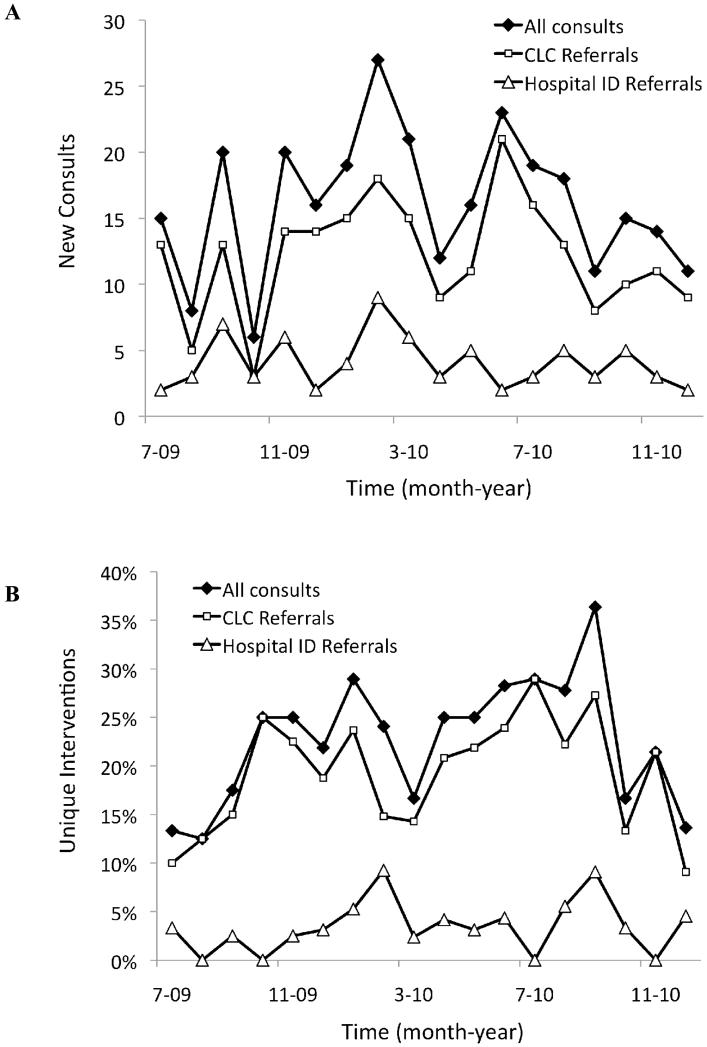

Between July 2009 and December 2010, the LID service completed 291 consultations on 250 individual patients. The CLC staff initiated the majority of consultations (n = 218, 75%) compared to the hospital ID service (n = 73, 25%). Figure 1A shows that these differences were largely consistent over the duration of the study.

Figure 1.

The number of new consultations (A) and the percentage of interventions (B) made by the LID service during the study period.

Table 1 compares the demographics and characteristics of CLC residents seen in consultation by the LID service, comparing those referred by the hospital ID service vs. the CLC staff. Patients identified by the hospital ID service were younger (65.2 vs. 70.7 years, P < .001) and more likely to be on antibiotics (84% vs. 47%, P < .001) compared to those referred by the CLC staff. While there were no significant differences by referral source for laboratory values or Braden score [12], there was a trend towards a lower albumin among residents referred by the hospital ID service.

Table 1.

Characteristics of LTCF Residents Seen by the LID Service According to Referral Source

| Referral Source |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Data | All Individuals (N = 250) |

CLC (n = 182) |

Hospital ID (n = 68) |

P-valuea |

| Age at First Visit, mean ± SDb | 69.3 ± 12.7 | 70.7 ± 12.8 | 65.2 ± 11.9 | <.001 |

| Age > 85, n (%) | 36 (14%) | 32 (18%) | 4 (6%) | .03 |

| Male, n (%) | 247 (99%) | 182 (98%) | 68 (100%) | .17 |

| Race or Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 153 (61%) | 118 (65%) | 35 (52%) | .07 |

| African-American | 78 (31%) | 49 (27%) | 29 (43%) | .17 |

| Other Races & Ethnicitiesc | 19 (8%) | 15 (8%) | 4 (6%) | .48 |

| Died During Study Period, n (%) | 76 (30%) | 63 (35%) | 13 (19%) | .03 |

| Characteristics upon Referral | All Referrals (N = 291) |

CLC (n = 218) |

Hospital ID (n = 73) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| On antibiotics at first consult visit, n (%) |

163 (56%) | 102 (47%) | 61 (84%) | <.001 |

| Laboratory Values at First Visit, mean ± SDd | ||||

| White Blood Cell Count (K/cmm) |

9.04 ± 5.22 | 9.02 ± 4.60 | 9.09 ± 6.62 | .75 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.7 ± 2.00 | 10.8 ± 1.98 | 10.45 ± 2.07 | .22 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.41 ± 1.10 | 1.5 ± 1.19 | 1.25 ± 0.79 | .23 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.67 ± 0.65 | 2.75 ± 0.64 | 2.46 ± 0.66 | .01 |

| Braden, mean + SDe | 17.29 ± 2.87 | 17.10 ± 2.90 | 17.93 ± 2.69 | .02 |

Compares consultations by referral source. Chi-square test for nominal values; Wilcoxon signed-rank test for continuous variables; with Bonferroni correction, significant P-value ≤ .0038.

SD, standard deviation.

Includes Hispanic, Asian, Native American, Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian and Unknown.

Determined within 7 days before or after the initial consult.

Determined within 7 days before or 30 days following the initial consult.

Table 2 shows the wide array of infection-related conditions among CLC residents seen by the LID team. The most common diagnosis was Clostridium difficile infection (14%) followed by urinary tract infection (10%) and asymptomatic bacteriuria (10%). The hospital ID consult service was more likely to refer CLC residents with infections requiring long-term intravenous antibiotics, such as bacteremia or line infection, septic arthritis or prosthetic joint infection, and endocarditis (P < .001 for all three conditions). In contrast, the CLC staff were more likely to refer individuals with asymptomatic bacteriuria or other conditions ultimately deemed not to be infections; these differences did not reach statistical significance.

Table 2.

Diagnoses of LTCF Residents Seen by the LID Service According to Referral Source

| Referral Source |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnoses, n (%) | All Referrals (N = 306) |

CLC (n = 232) |

Hospital ID (n = 74) |

P-valuea |

| Clostridium difficile infection | 43 (14.1%) | 38 (16.4%) | 5 (6.8%) | .06 |

| Urinary Tract Infection | 30 (9.8%) | 26 (11.2%) | 4 (5.4%) | .22 |

| Asymptomatic Bacteriuria | 29 (9.5%) | 29 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | .003 |

| Non-infectious Diagnosis | 29 (9.5%) | 28 (12.1%) | 1 (1.4%) | .01 |

| Wound infection/Pressure Ulcer | 26 (8.5%) | 17 (7.3%) | 9 (12.2%) | .29 |

| Pneumonia | 23 (7.5%) | 21 (9.1%) | 2 (2.7%) | .12 |

| Osteomyelitis/Epidural Abscess | 19 (6.2%) | 10 (4.3%) | 9 (12.2%) | .03 |

| Bacteremia/Line Infection | 15 (4.9%) | 4 (1.7%) | 11 (14.9%) | <.001 |

| Prosthetic Joint Infection/Septic Arthritis |

13 (4.2%) | 4 (1.7%) | 9 (12.2%) | <.001 |

| Endocarditis | 10 (3.3%) | 2 (0.9%) | 8 (10.8%) | <.001 |

| Tuberculosis (latent and active) | 9 (2.9%) | 7 (3.0%) | 2 (2.7%) | .80 |

| Skin & Soft Tissue Infection | 8 (2.6%) | 6 (2.6%) | 2 (2.7%) | .72 |

| Upper Respiratory Infection | 6 (2.0%) | 6 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | .29 |

| Diabetic Foot Infection | 6 (2.0%) | 6 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | .36 |

| Diarrheab | 5 (1.6%) | 5 (2.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | .46 |

| Pancreatitis/Cholecystits | 5 (1.6%) | 4 (1.7%) | 1 (1.4%) | .76 |

| Abdominal Abscess/Enteric Fistula | 5 (1.6%) | 4 (1.7%) | 1 (1.4%) | .76 |

| Otherc | 25 (8.2%) | 15 (6.5%) | 10 (13.5%) | .09 |

Compares consultations by referral source using Chi-square test; with Bonferroni correction, significant P-value ≤ .002.

Acute diarrhea not due to C. difficile infection.

Includes 4 consults each for shingles and perirectal abscess, 3 consults each for HIV/AIDS, bursitis and empyema, 2 consults for lung abscess and 1 consult each for a tracheostomy infection, meningitis, endopthalmitis, hyradenitis suppurativa, psoas abscess and scrotal abscess.

The LID team recommended changes for 46% of the consultations, all of which were accepted by the primary service (Table 3). Stopping antibiotics (32%) was the most frequent intervention, followed by starting antibiotics (26%), changing therapy due to contraindications (14%), decreasing length of therapy (7%) and deescalating therapy (7%). These decisions were based on culture results when available and in accordance with the principles of antibiotic stewardship. Consultations originating from the hospital ID service were less likely to need an intervention compared to those referred by the CLC staff (30% vs. 51%; P = .003). The relationship between referral source and the likelihood of needing an intervention remained significant even after controlling for patient age, race or ethnicity, laboratory values, Braden score, hospital transfer, and diagnosis (adjusted odds ratio (AOR)= 0.40; 95% Confidence Interval (CI)= 0.19-0.78). Figure 1B shows there was no sustained decline in the interventions over time.

Table 3.

Interventions from the LID Team According to Referral Source

| Referral Source |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventions, n (%) | All Referrals (N = 291) |

CLC (n = 218) |

Hospital ID (n = 73) |

P-valuea |

| Total interventionsb | 134 (46%) | 112 (51%) | 22 (30%) | .003 |

| Stop Antibiotic | 43 (32%) | 39 (35%) | 4 (18%) | .11 |

| Start Antibiotic | 35 (26%) | 33 (30%) | 2 (9%) | .15 |

| Change Therapy Due to a Contraindication |

19 (14%) | 13 (12%) | 6 (27%) | .99 |

| Decrease Length of Therapy | 9 (7%) | 9 (8.0%) | 0 (0%) | .29 |

| Deescalate Therapy | 9 (7%) | 7 (6%) | 2 (9%) | .84 |

| Transfer to the hospital | 7 (5%) | 6 (5%) | 1 (5%) | .71 |

| Diagnostic Imaging or Labs | 6 (4%) | 5 (4%) | 1 (5%) | .58 |

| Adjust Dose | 4 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (14%) | .03 |

| Evaluate & Treat a Non- Infectious Condition |

4 (3%) | 4 (4%) | 0 (0%) | .01 |

| Otherc | 6 (4%) | 3 (3%) | 3 (14%) | .09 |

Compares consultations by referral source using Chi-square test; with Bonferroni correction, significant P-value ≤ .0045.

Some consultations involved more than one intervention.

Includes stop loperimide (n = 2), start antiretrovirals (n = 2), increase length of therapy (n = 1) and change urinary catheter (n = 1).

The follow-up period was < 30 days for most consults (74%) although a few patients (9%) were followed for >90 days. The majority of consults (76%) required 3 or fewer interactions. A minority of patients (8%) needed follow-up in the outpatient ID clinic after discharge from the CLC. Their diagnoses were osteomyelitis (6 patients); lung abscess, pneumonia or empyema (5 patients); septic arthritis or prosthetic joint infection (3 patients); endocarditis (2 patients); Clostridium difficile infection (2 patients); skin and soft tissue infections (2 patients); HIV/AIDS (2 patients) and tuberculosis (1 patient).

A total of 45 CLC residents were admitted to the hospital during or within 30 days following their last interaction with the LID team. Eighty percent of these admissions were for infectious disease-related conditions. Patients referred by the CLC staff and the hospital ID service were equally likely to require hospital admission (14% vs. 16% respectively, P = 0.77). The relationship between referral source and the likelihood of hospital transfer remained non-significant after controlling for patient age, race or ethnicity, laboratory values, Braden score, intervention, and diagnosis in multivariate logistic regression (AOR= 0.73, 95% CI= 0.26-1.97). Seven of the 45 transfers (15%) were on the recommendation of the LID team. The most common infection-related reasons for a patient followed by the LID team to require hospital admission were for pneumonia (22%) or wound infection (22%), followed by C. difficile infection (9%) and bacteremia or sepsis (9%). The LID team recommended hospice/palliative care consults for 8 CLC residents, all of whom had infectious concerns related to the end of life: recurrent aspiration pneumonia; multiple recurrences of severe Clostridium difficile infection; severe decubitus ulcers or chronic osteomyelitis in bed-bound patients. One patient had prosthetic valve endocarditis with an aortic root abscess and was deemed a poor surgical candidate.

Discussion

The LID service met a previously unidentified need for subspecialty expertise at our CLC, providing patient-centered care through once weekly rounds and as needed communication via the electronic medical record and phone conversations. It also permitted successful implementation of antimicrobial stewardship within a LTCF setting, which has been strongly recommended in a policy statement issued by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS) [14,15]. During the study period, neither the rate of consultations nor the proportion of interventions showed a sustained decrease, suggesting that the CLC staff continued to rely upon the LID service for guidance.

The CLC residents carried a wide array of ID-related diagnoses. These included common conditions like pneumonia and urinary tract infections as well as unusual manifestations of familiar diagnoses such as purple urine bag syndrome in a patient with asymptomatic bacteriuria. The LID team also evaluated patients with infrequent conditions (e.g. endophthalmitis, bacteremia due to Listeria monocytogenes) or with concerns for emergent conditions (e.g. severe sacral wound infection vs. Fournier’s gangrene).

Even for those patients referred by the hospital ID consult service, 30% required an intervention from the LID team during their follow-up, an indication that active management is necessary for these medically complex individuals. Some interventions primarily addressed laboratory findings, such as vancomycin dosing and adjusting antimicrobial doses in response to changing renal function. Other interventions required clinical assessment, including evaluation of a rash as a potential allergic reaction and finding, based on symptoms, an epidural abscess in a patient on treatment for endocarditis. The younger average age among patients referred by the hospital ID service likely reflects the increased severity of illness among those with conditions that warrant hospital ID consultation (i.e. bacteremia/line infection, prosthetic joint infection/septic arthritis and endocarditis).

To our knowledge, this is the first description of an ID consultation service that brings expertise specifically to LTCF residents. An example of successful integration of subspecialty care into LTCFs comes from the mental health professions. Under the Nursing Home Reform and Amendments of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 (OBRA), people admitted to LTCF must undergo screening for major psychiatric disorders with subsequent evaluation if psychiatric illness is suggested [16]. The Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) supports and provides fiscal compensation for mental health professionals who see LTCF residents, which underscores that addressing mental health concerns among this frail population has become a routine practice mandated by policy [17]. The need to bring other medical services to LTCFs, however, has not yet been similarly recognized. As such, even reimbursement for routine visits, the amount of non-reimbursable activities, and logistics continue to pose significant barriers to establishing subspecialty LTCF consultation practices [18]. Under the current Medicare payment policy, skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) receive a per diem payment for residents, regardless of increased costs related to acute illnesses [19]. Individual SNFs do not realize any cost savings by avoiding resident transfer to an acute care setting. Furthermore, a 3-day inpatient stay may qualify residents with Medicaid coverage for Medicare Part A payments for post-acute care, at a rate 3-fold higher than the usual Medicaid daily rate [20]. These rules may contribute to sending LTCF residents to emergency rooms and hospitals, even for illnesses that might readily be managed within the LTCF. With improved access to medical providers at the LTCF, including subspecialists, it is possible that residents could avoid some hospital admissions. Telemedicine, which has improved some LTCF residents’ access to psychiatric care [21], may also provide another means to facilitate managing residents’ medical illnesses at the LTCF.

Our study has several limitations. First, we report our experience at a single VA-affiliated CLC, which may limit implementation of a similar service in other LTCF settings. The CLC in our study admits veterans nearly exclusively from the affiliated VA hospital. Typical community-based LTCFs accept patients from a wide array of settings, including multiple hospitals. Furthermore, VA healthcare comprises a closed system connected by a common electronic medical record. This greatly facilitates transfer of information between providers in the hospital, CLC and outpatient clinics. This advantage is lost outside of large healthcare networks. Additionally, the providers caring for the residents were permanent staff at the CLC, which not only facilitated communication with the LID team during rounds, but also led to the development of a collaborative relationship over time. Finally, the most notable factor that limits applicability of this model outside of the VA system is one of financial compensation. Both members of the LID team were staff providers at the VA hospital and thus did not have to contend with obtaining reimbursement.

Future directions for the LID service include incorporation of a pharmacist to review antimicrobial prescriptions for appropriateness of the indication, dose, length of therapy and drug-drug interactions. Other initiatives will address means to help the CLC staff become more knowledgeable regarding evaluating residents for suspected infections with the goal of reducing their dependence on the LID team. It is our hope that this experience will encourage development of similar programs to address diagnoses common among VA CLC residents including congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as well as podiatric and urologic problems. Finally, we are hopeful that offering ID consultations to VA CLC residents will lay the groundwork for developing similar programs, with accompanying support among policy makers, for community-based LTCFs.

Acknowledgements

RLPJ gratefully acknowledges the T. Franklin Williams Scholarship with funding provided by Atlantic Philanthropies, Inc.; the John A. Hartford Foundation, the Association of Specialty Professors, the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R03-AG040722 to RLPJ, R01-AI063517 to RAB), by the Veterans Affairs Merit Review Program (RAB, CJD) and the Veterans Integrated Service Network 10 Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (VISN 10 GRECC; RLPJ, LAJ, BS, RAB, CJD).

Sponsor’s Role: None

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: All authors report no conflicts of interest. RLPJ reports having consulted for GOJO and Pfizer and has received grant support from Steris, Merck and ViroPharma. RAB reports having consulted for AstraZeneca and having received grant support from AstraZeneca, Ribx, Pfizer and Steris. CJD reports having consulted for BioK, Optimer and GOJO and has received grant support from ViroPharma, Merck and Pfizer.

Author Contributions: RLPJ and LAJ comprised the LID team. RLPJ and DMO designed the research study. RLPJ, BS and ES abstracted and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to drafting and editing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Nursing Home Week — May 8-14, 2005. MMWR. 2005;54:438. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones AL, Dwyer LL, Bercovitz AR, et al. The National Nursing Home Survey: 2004 overview. Vital Health Stat. 2009;13:1–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones A. The National Nursing Home Survey: 1999 summary. Vital Health Stat. 2002;1313:1–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crnich CJ, Drinka P. Medical device-associated infections in the long-term care setting. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2012;26:143–164. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strausbaugh LJ, Sukumar SR, Joseph CL, et al. Infectious disease outbreaks in nursing homes: An unappreciated hazard for frail elderly persons. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:870–876. doi: 10.1086/368197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caprio TV, Karuza J, Katz PR. Profile of physicians in the nursing home: Time perception and barriers to optimal medical practice. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10:93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.High KP, Bradley SF, Gravenstein S, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation of fever and infection in older adult residents of long-term care facilities: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:149–171. doi: 10.1086/595683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vladeck BC. The continuing paradoxes of nursing home policy. JAMA. 2011;306:1802–1803. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.VanSchooneveld TV, Miller H, Sayles H, et al. Survey of antimicrobial stewardship practices in Nebraska long-term care facilities. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:732–734. doi: 10.1086/660855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicolle LE, Bentley DW, Garibaldi R, et al. Antimicrobial use in long-term-care facilities. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21:537–545. doi: 10.1086/501798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peron EP, Hirsch AA, Jump RLP, et al. Don’t Let the Steward Sail Without Us: High Rate of Unncessary Antimicrobial Use in Long-Term Care Facility; 50th Inter-science Conference of Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC); Boston, MA. September 12-15, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braden B, Bergstrom N. A conceptual schema for the study of the etiology of pressure sores. Rehabil Nurs. 1987;12:8–12. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.1987.tb00541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.R Development Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2012. Available at: URL http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jump RLP, Olds DM, Seifi N, et al. Effective antimicrobial stewardship in a long-term care facility through an infectious disease consultation service: Keeping a LID on antibiotic use. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:1185–1192. doi: 10.1086/668429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Policy statement on antimicrobial stewardship by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS) Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:322–327. doi: 10.1086/665010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta S, Goldstein MZ. Practical geriatrics: Psychiatric Consultation to Nursing Homes. PSS. 1999;50:1547–1550. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molinari V, Hedgecock D, Branch L, et al. Mental health services in nursing homes: A survey of nursing home administrative personnel. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13:477–486. doi: 10.1080/13607860802607280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy C, Palat S-IT, Kramer AM. Physician practice patterns in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8:558–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desmarais H. [Accessed 23 November 2012];Financial Incentives in the Long-Term Care Context: A First Look at Relevant Information. 2010 Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicare/upload/8111.pdf.

- 20.Ouslander JG, Berenson RA. Reducing Unnecessary hospitalizations of nursing home residents. NEJM. 2011;365:1165–1167. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1105449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyketsos CG, Roques C, Hovanec L, et al. Telemedicine use and the reduction of psychiatric admissions from a long-term care facility. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2001;14:76–79. doi: 10.1177/089198870101400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]