Abstract

Coccidioides is the causative agent of a potentially life-threatening respiratory disease of humans. A feature of this mycosis is that pH measurements of the microenvironment of pulmonary abscesses are consistently alkaline due to ammonia production during the parasitic cycle. We previously showed that enzymatically active urease is partly responsible for elevated concentrations of extracellular ammonia at sites of lung infection and contributes to both localized host tissue damage and exacerbation of the respiratory disease in BALB/c mice. Disruption of the urease gene (URE) of C. posadasii only partially reduced the amount of ammonia detected during in vitro growth of the parasitic phase, suggesting that other ammonia-producing pathways exist that may also contribute to the virulence of this pathogen. Ureidoglycolate hydrolase (Ugh) expressed by bacteria, fungi and higher plants catalyzes the hydrolysis of ureidoglycolate to yield glyoxylate and the release CO2 and ammonia. This enzymatic pathway is absent in mice or humans. Ureidoglycolate hydrolase gene deletions were conducted in a wild type (WT) isolate of C. posadasii as well as the previously generated Δure knock-out strain. Restorations of UGH in the mutant stains were performed to generate and evaluate the respective revertants. The double mutant revealed a marked decrease in the amount of extracellular ammonia without loss of reproductive competence in vitro compared to both the WT and Δure parental strains. BALB/c mice challenged intranasally with the Δugh/Δure mutant showed 90% survival after 30 days, decreased fungal burden, and well-organized pulmonary granulomas. We conclude that loss of both Ugh and Ure activity significantly reduced the virulence of this fungal pathogen.

Keywords: Ammonia production, Virulence factor, Coccidioides, Coccidioidomycosis

1. Introduction

Coccidioides is a dimorphic fungal pathogen and causative agent of a human respiratory disease known as coccidioidomycosis or San Joaquin Valley fever. The genus includes two morphologically indistinguishable species, Coccidioides posadasii and C. immitis [1]. The saprobic phase of C. posadasii occurs in arid, alkaline soil in southwestern regions of the United States between West Texas and Southern California, as well as parts of Mexico and Central and South America. Occurrence of C. immitis, on the other hand, appears to be geographically restricted to the San Joaquin Valley of California. The two species have been reported to be comparable in pathogenicity in humans and experimental animals based on clinical observations and studies of the disease in mice [2, 3]. However, a critical comparative evaluation of the relative virulence of C. immitis and C. posadasii has not been conducted. Coccidioides is an Ascomycete, classified in the order Onygenales and related to other genera of fungal pathogens with morphogenetically distinct saprobic and parasitic phases, including Blastomyces, Histoplasma and Paracoccidioides that also cause potentially life-threatening respiratory diseases in humans [4]. The saprobic phase of Coccidioides grows as a filamentous (hyphal) form and produces small, dry spores (arthroconidia) which are released into the air upon disturbance of the soil. These infectious propagules may be inhaled by burrowing desert rodents in endemic regions and could serve as reservoirs of the fungus. The spores of Coccidioides are small enough to reach and colonize the lower limits of the respiratory tree [5]. Non-human primates experimentally exposed to an aerosol containing as few as 10 to 50 Coccidioides spores have been shown to develop symptomatic disease and die within 4–6 weeks postchallenge [6, 7]. In vivo the spores grow isotropically and develop into large, multinucleate parasitic cells (spherules; > 80 μm diam.). The latter undergo a process of segmentation of their cytoplasm followed by differentiation of a multitude of endospores (approx. 200–300) which are still contained within the intact spherule wall. The contents of the spherule are finally released when the endospores enlarge and cause the spherule wall to rupture. First generation parasitic cells grown in vitro reveal near synchronization of their developmental stages between initiation of spore germination and endospore release from mature spherules [8]. Each endospore can differentiate into a second generation spherule and the parasitic cycle is thereby repeated in infected lung tissue.

Although Coccidioides is recognized as the causative agent of an intransigent infectious disease by physicians who treat patients with the life-threatening, disseminated form of coccidioidomycosis, few virulence factors have been identified for this pathogen [9]. A candidate factor is the propensity of Coccidioides to generate high concentrations of extracellular ammonia at sites of lung infection resulting in an alkaline microenviroment during growth of its parasitic phase in vivo, a condition which has been suggested to compromise host cellular immune defenses [10]. Coccidioides has been reported to tolerate a broad pH range but prefers to grow in an alkaline habitat [11]. When incubated in an acidic, sugar-free medium the fungus is induced to release ammonia and ammonium ions in quantities that sharply increase the pH of its extracellular environment [10]. The contents of mature spherules released upon rupture of the spherule wall in vitro have been stained with a dual emission pH indicator dye (seminaphthorhodafluor [SNARF]), examined by fluorescence microscopy, and shown to be distinctly alkaline [12]. A standard curve for pH estimates was established on the basis of SNARF fluorescence emission ratios using buffers with a pH range of 5.0 to 9.0. The average pH of the surface of endospores released from ruptured spherules was 8.2, while the average pH of the surface of intact, first generation spherules prior to endospore differentiation was 7.6. We have previously reported that ammonia and enzymatically active urease released from parasitic cells of C. posadasii contribute to host tissue damage and exacerbate the severity of coccidioidal lung infections [10, 13]. Direct measurement of the pH of lung abscesses of BALB/c mice infected with C. posadasii revealed a mean value of 7.7, while the average internal pH of abscesses in mice infected with a urease gene deletion mutant was 7.2 [10]. It is reasonable to speculate that maintenance of an alkaline microenvironment by both the saprobic and parasitic forms of Coccidioides could be an effective mechanism to compete with other microbes and protect against hostile defense cells of the infected mammalian host. Bacterial urease activity, particularly in Helicobacter pylori and Proteus mirabilis, has been shown to be a major source of ammonia and an important microbial virulence factor [14–16]. Amongst the medically important fungi ammonia production has been associated with pathogenicity only in Cryptococcus and Coccidioides [10, 17]. Disruption of the single urease gene (URE) of C. posadasii resulted in reduced but not total loss of extracellular ammonia detected in vitro [10]. BALB/c mice inoculated intranasally with a potentially lethal spore suspension derived from the Δure mutant showed 55% survival after 60 days compared to no survivors among the group of control mice by 18 days postchallenge. We have speculated that sources of extracellular ammonia production in addition to the hydrolysis of urea contribute to the pathogenicity of Coccidioides. In this study we provide evidence that ureidoglycolate hydrolase activity, associated with the conserved allantoin degradation pathway in bacteria, fungi and plants, is also responsible in part for the extracellular ammonia detected during the parasitic cycle of C. posadasii and together with urease activity contributes significantly to the virulence of this fungal pathogen.

2. Results

2.1. Ureidoglycolate hydrolase is a component of the allantoin degradation pathway of Coccidioides posadasii

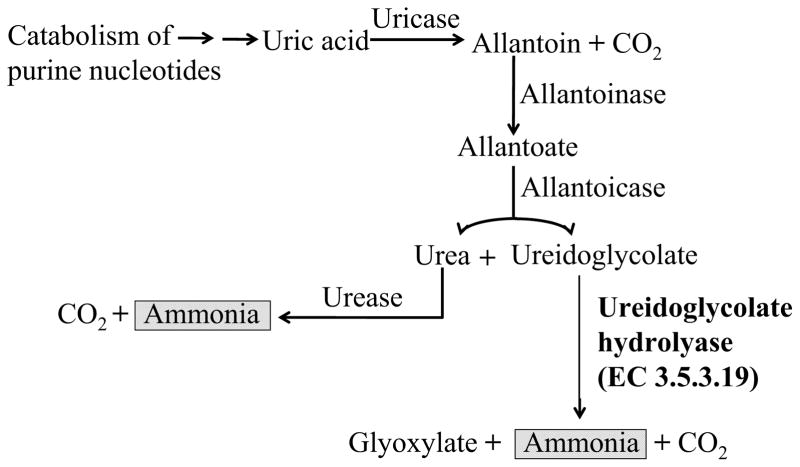

Uric acid is a product of purine metabolism. In humans it forms salts known as urates which are the final products of purine degradation and are excreted in urine. In microoganisms further catabolism of purines has been shown to provide both an important source of recycled nitrogen for growth and reproduction as well as a mechanism to get rid of excess nitrogen [18, 19]. Ureides (allantoin and allantoate) are products of uric acid hydrolysis (Fig. 1) and undergo a series of degradative steps to release nitrogen as ammonia [20]. The first two steps of allantoin catabolism occur in the presence of allantoinase and allantoicase, which are conserved proteins amongst bacteria and fungi. Separate BLAST searches of the NCBI protein database were conducted using the reported sequences of allantoinase (GenBank accession nos. XP_003065422) and allantoicase (EFW20684) of C. posadasii as queries which revealed 64–77% and 63–76% sequence similarities with the respective homologs reported for other filamentous fungi. At least two alternative metabolic pathways exist following the hydrolysis of allantoate in microorganisms. One pathway results in the release of urea and its full catabolism to ammonia and CO2 while another gives rise to ureidoglycine, an unstable intermediate which spontaneously releases ammonia upon hydrolysis in the presence of ureidoglycine aminohydrolase to yield ureidoglycolate[19, 21]. BLAST searches of all available Coccidioides genome databases (http://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/genome/coccidioidesgroup/Genomes) using the reported ureidoglycine aminohydrolase of E. coli as the query (GenBank accession no. CCQ07550) failed to identify a Coccidioides homolog of this enzyme. Ureidoglycolate may be produced directly from the hydrolysis of allantoate in Coccidioides. Ureidoglycolate is the final substrate of the allantoin degradation pathway [20] and its hydrolysis in the presence of ureidoglycolate hydrolase (Ugh) yields glyoxylate, ammonia and CO2 (Fig. 1). C. posadasii has a single UGH gene with no intron (GenBank accession no. EER28584) that encodes a protein of 268 amino acids. The protein is conserved in filamentous fungi, yeast and bacteria (Table 1) [22]. Expression of both the C. posadasii allantoicase gene and UGH have been reported to be up-regulated during in vitro growth of the parasitic phase compared to their expression during saprobic phase growth [3].

Fig. 1.

Proposed pathway of degradation of purines in Coccidioides posadasii [18]. Identification of the enzymatic steps of allantoin catabolism is based on results of comparative genomics. Allantoinase (allantoin amidohydrolase), allantoicase (allantoate amidinohydrolase) and ureidoglycolate hydrolase (ureidoglycolate amidohydrolase) are conserved in fungi and bacteria [19–21]. Two sources of ammonia which are relevant to this study are highlighted.

TABLE 1.

Summary of calculated values for amino acid sequence similarities and identities between the deduced UGH of C. posadasii and reported UGH sequences of selected filamentous fungi, yeast and bacteria

| Sequence source | GenBank accession number | Similarity (%)a | Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus fumigatus | EDP48832 | 65 | 49 |

| Ajellomyces dermatitidis | XP_002625402 | 58 | 49 |

| Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | EEH17539 | 57 | 45 |

| Magnaporthe oryzae | XP_003715064 | 51 | 38 |

| Fusarium oxysporum | EGU87042 | 56 | 40 |

| Neurospora crassa | XP _955860 | 49 | 37 |

| Candida albicans | XP _711549 | 47 | 34 |

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe | NP_594419 | 44 | 31 |

| Burkholderia sp. | ZP _10036133 | 39 | 25 |

| Acinetobacter sp. | ZP _10187294 | 39 | 28 |

Based on CLUSTAL X alignment of amino acid sequences, taking into account conservative substitutions of residues [22].

2.2. Elevated expression of UGH correlates with differentiation and release of endospores from mature spherules

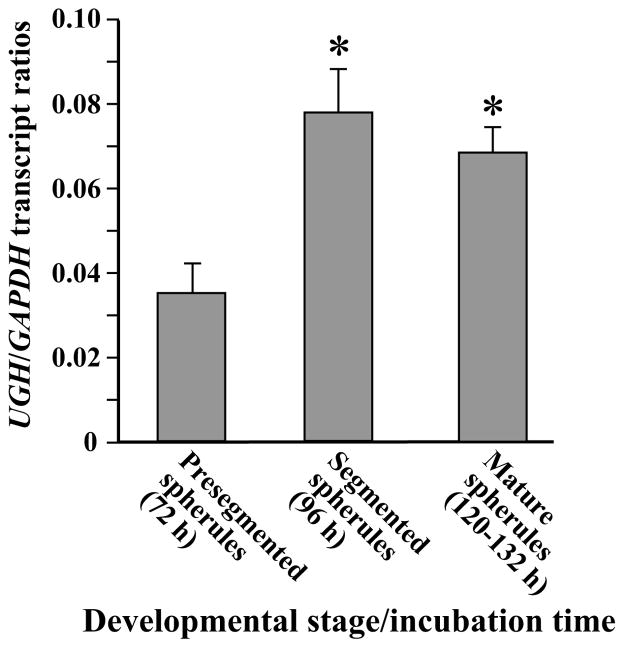

Quantitative analysis of UGH expression in vitro was conducted with total RNA isolated from three distinct stages of parasitic cell development (Fig. 2). Spherules cultured for 72 h are well synchronized in development and represent the beginning of the segmentation process [10]. By 96 h initiation of endospore differentiation had occurred and by 120 h endospores typically filled the spherule cavity while the outer spherule wall remained intact. A significant increase in UGH expression was consistently observed between 72 h and 96 h of incubation of the parasitic phase, and the relative amount to gene transcript remained high through the later maturation stage (132 h) when spherules ruptured and released their contents.

Fig. 2.

Results of QRT-PCR analysis of UGH expression during in vitro parasitic phase growth of the WT strain of C. posadasii. Amounts of UGH transcript detected during specific developmental stages of parasitic cells were compared to expression levels of the constitutive GAPDH gene. The asterisks indicate statistically significant difference between the presegmentation and later stages of spherule maturation. This assay was conducted in triplicate.

2.3. Generation of the UGH-deficient and UGH-reconstituted (revertant) strains

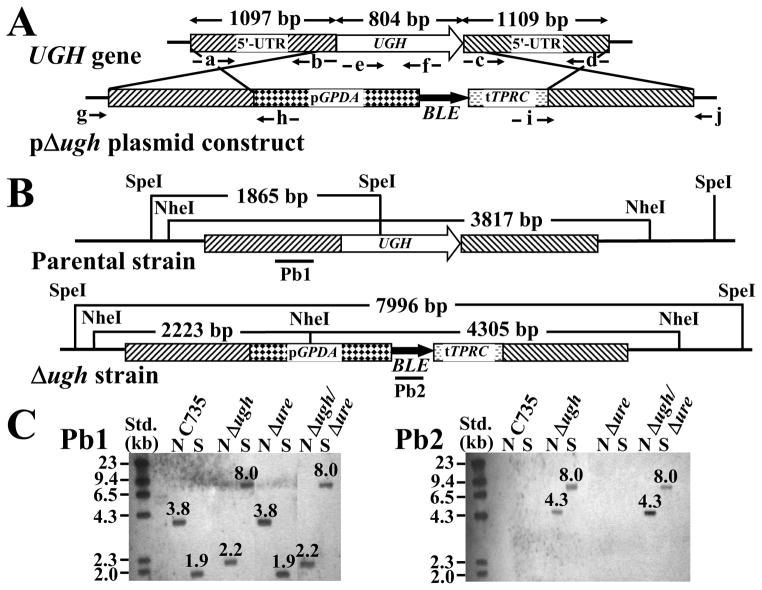

Our previously reported gene-targeted disruption and replacement strategies used to create mutants of C. posadasii have proved to be efficient processes in our hands [23–25]. In this study, a linearized 5.8-kb plasmid construct (pΔugh; Fig. 3A) was used to integrate into the chromosomal DNA of both the WT strain and a previously reported Δure mutant of C. posadasii [10]. The plasmid construct replaced the UGH gene by a targeted double cross-over event. Transformation of approximately 3×107 germ tube- protoplasts derived from the WT and Δure parental strains with 15 μg of the plasmid DNA construct yielded more than 200 colonies that were resistant to phleomycin. The colonies derived from transformation of the Δure parental strain were resistant to both hygromycin and phleomycin. PCR screening of 24 candidate transformants of each strain indicated that 16 and 2 of the WT- and Δure-derived colonies, respectively, had undergone homologous recombination. The location of the forward and reverse olignucleotide primers (a-j) used for PCR screening are indicated in Fig. 3A. Two of these putative transformants, referred to as Δugh and Δugh/Δure, were selected for further analysis by Southern hybridization. For purposes of probe selection and restriction of genomic DNA in preparation for hybridization, two restriction maps were constructed (Fig. 3B). A restriction map was generated for the 9.7-kb genomic fragment of the two parental strains that included the UGH gene. A restriction map was also generated based on the hypothetical structure of the integrated chromosomal fragment that contained the pΔugh plasmid. A 611-bp amplicon of the 5′-UTR of UGH (Pb1) and a 393-bp amplicon of the BLE gene (Pb2) were used as probes to conduct Southern hybridization analyses of the parental strains and selected transformants. The results of separate hybridization of these two probes with SpeI and NdeI digests of the respective genomic DNAs are shown in Fig. 3C. Single bands of predicted size were detected by hybridization with each of the DNA digests derived from the Δugh and Δugh/Δure transformants, which indicated that the UGH gene had been deleted by homologous recombination and the plasmid construct had inserted at a single chromosomal locus.

Fig. 3.

(A) Ureidoglycolate hydrolase gene (UGH) structure and replacement strategy used for its deletion. The coding region of UGH was replaced by a double cross-over event between chromosomal DNA and the pΔugh plasmid construct. Primers used to PCR amplify the 5′-UTR and 3′-UTR fragments of genomic DNA for cloning into the plasmid construct, as well as primers used to screen for transformants containing the integrated plasmid construct are indicated (see Table 2). (B) Restriction map of the 9.7-kb chromosomal fragment that contained the UGH gene, and hypothetical restriction map of the pΔugh deletion construct integrated into chromosomal DNA. Pb1 and Pb2 are genomic probes used for Southern hybridization. (C) Results of Southern hybridization of NheI (N)- and SpeI (S)-restricted genomic DNA derived from the parental (C735), and mutant strains carrying either the single gene deletions (Δugh, Δure) or double gene deletion (Δugh/Δure). The sizes of the hybridized fragments correlated with both the UGH restriction map and predicted sizes in the hypothetical restriction map.

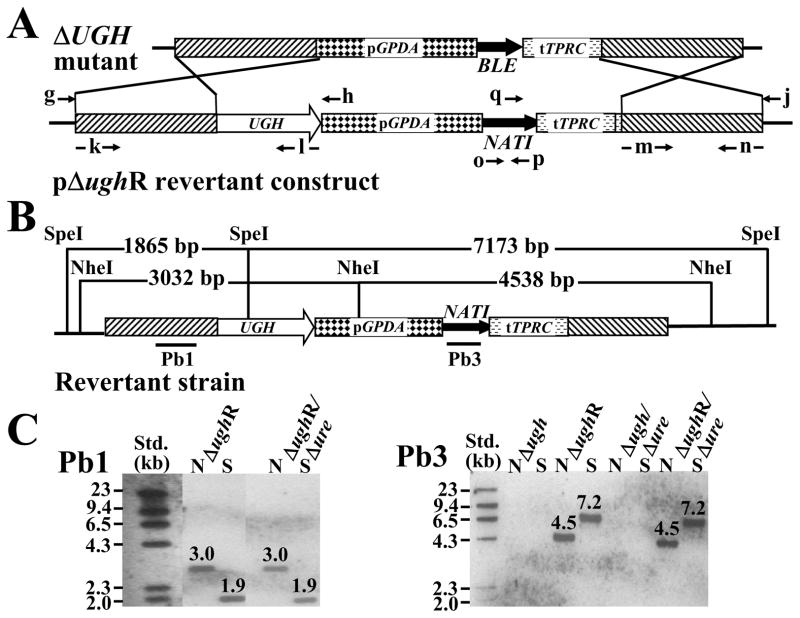

A pAN9.1 plasmid containing the NAT1 gene that encodes a nourseothricin resistance protein was ligated to the parental UGH gene and used for transformation of the Δugh and Δugh/Δure mutants to generate the reconstituted (revertant) strains (Fig. 4A). Transformation of approximately 5×107 protoplasts with 15 μg of the 6.9-kb linearized plasmid DNA yielded more than 250 colonies which were resistant to nourseothricin. Separate PCR screening of 30 transformants derived from each of the Δugh and Δugh/Δure parental strains revealed that 2 and 5 isolated colonies, respectively, had apparently undergone homologous transformation. The location of the forward and reverse oligonucleotide primers used for the PCR screens are indicated in Fig. 4A. These putative transformants were subsequently screened by Southern hybridization. A hypothetical restriction map of the plasmid construct integrated into the chromosomal DNA of the revertant strains is shown in Fig. 4B. Separate genomic DNAs isolated from the selected transformants were restricted with SpeI and NheI and then hybridized with the Pb1 probe as above or a 695-bp amplicon of the NAT1 gene (Pb3). Bands of the predicted sizes were detected which provided evidence that the revertant strains contained single copies of the wild-type UGH gene. Results of Southern hybridization thereby confirmed that the plasmid construct used to reconstitute the wild type UGH gene had successfully integrated into chromosomal DNA of the mutant host strains by a double cross-over event at a single locus and generated the revertant strains ΔughR and ΔughR/Δure (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

(A) Structure of Δugh mutant and plasmid structure used for restoration of the UGH gene and generation of the revertant strains. Primers used for PCR screening of putative transformants are indicated (see Table 2). (B) Hypothetical restriction map of chromosomal fragment of revertant strain carrying the restored UGH gene. Pb3 is an amplicon of the NATI gene used as a probe for Southern hybridization (C) of NheI (N)- and SpeI (S)-restricted genomic DNA derived from the mutant and revertant strains (ΔughR and ΔughR/Δure).

2.4. Phenotypic comparison of the parental, mutant and revertant strains

The growth rate of the WT, mutant and revertant saprobic phases on GYE agar were near identical (data not shown). The mycelia of each strain was able to produce abundant spores after growth on agar plates for 4 weeks at 30°C. Each strain was also cultured in the defined glucose/salts and RPMI 1640 liquid media for microscopic examination of parasitic cell differentiation. The morphology and rate of spherule development in flask and plate cultures of both the mutant and revertant strains were comparable to that of the WT and Δure parental strains. In each case endospore differentiation was completed after approximately 6 days of incubation and the majority of spherules had ruptured and released their contents.

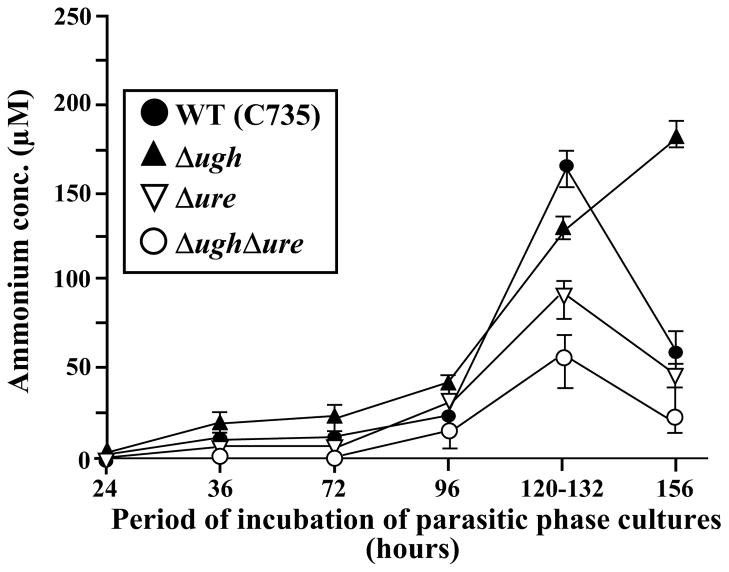

The amount of extracellular ammonia detected in RPMI 1640 media that supported growth of the parasitic phase over an incubation period of 24–156 h was measured by the Berthelot reaction (Fig. 5). During the initial 96 h, which corresponds with the isotropic growth and early segmentation phase, little ammonia was detected in the culture medium. After 120–132 h of incubation (period of endosporulation and spherule rupture) the double mutant (Δugh/Δure) showed a significantly lower concentration of extracellular ammonia than the WT strain (P <0.05). While the Δure mutant consistently showed higher amounts of ammonia compared to the double mutant after this same period of incubation, the concentration of extracellular ammonia of the former was also markedly lower than that of the WT strain. At 156 h of incubation (early isotropic growth of 2nd generation spherules) all strains except the Δugh mutant revealed a sharp decrease in extracelluar ammonia concentrations. On the other hand, deletion of the UGH gene resulted in enhanced production of ammonia as endospores matured and initiated differentiation of the next generation parasitic cells. The parental and corresponding revertant strains showed comparable amounts of ammonia released into the culture medium during each of the stages of parasitic development examined in Fig. 5 (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Comparative analysis of amounts of NH3/NH4+released by parasitic cells into the RPMI 1640 culture medium during incubation of each of the indicated strains for 24- 156 h. Spherule maturation and endospore release from ruptured spherules occurred between 120 h and 132 h of incubation. Concentrations of ammonia were determined by the Bertholet reaction as previously reported [13]. The data presented are representatitve of three separate assays.

2.5. Urease gene expression during parasitic phase growth of the Δugh mutant

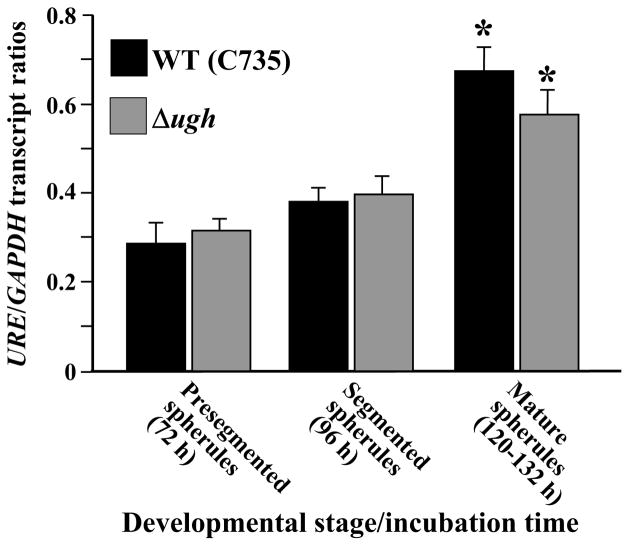

On the basis of the sustained elevated concentrations of extracellular ammonia detected during in vitro growth of second generation parasitic cells of the Δugh mutant we speculated that increased urease activity had compensated for the loss of function of the UGH gene. Results of quantitative real-time PCR analysis of urease gene expression revealed that a statistically significant increase in transcription occurred between stages of early spherule development (76–96 h) and endosporulation (120–132 h; P =0.008) in both strains (Fig. 6). However, no significant difference was observed between relative amounts of URE transcript detected in the WT compared to the Δugh strain during each of the stages parasitic phase growth.

Fig. 6.

Comparative QRT-PCR analysis of URE expression during incubation of parasitic phase cultures of the wild type (C735) and Δugh mutant strains. The asterisks indicate statistically significant difference between the spherule maturation stage and earlier developmental stages. This assay was conducted in triplicate.

2.6. Comparison of virulence of the parental, mutant and revertant strains

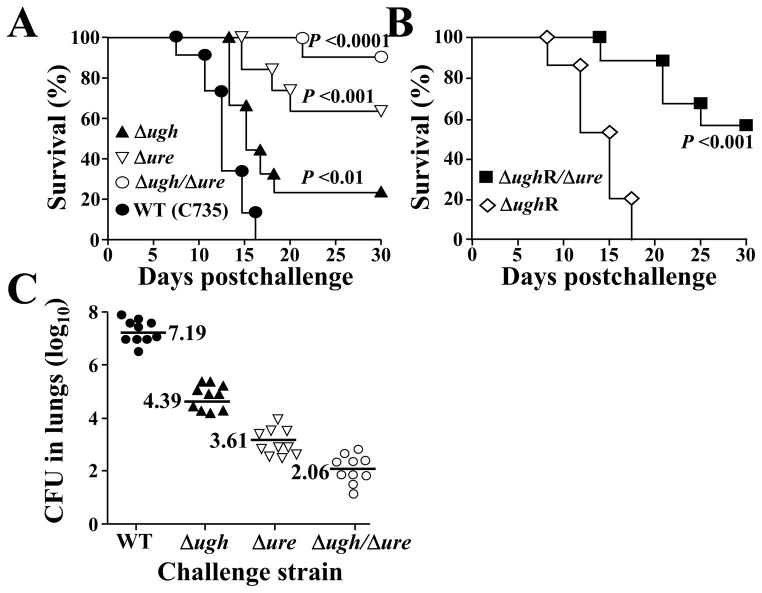

BALB/c mice are highly susceptible to coccidioidal infection when challenged intranasally with ~50 spores isolated from the saprobic phase of a virulent strain of Coccidioides [26, 27]. Equal numbers of spores (45 viable cells) isolated from the WT, mutant, and revertant strains were used to separately challenge six groups of BALB/c mice by the intranasal route (Fig. 7A,B). Mice inoculated with spores derived from the parental strains (WT or Δure; Fig. 7A) and the reconstituted (revertant) strains (ΔughR or ΔughR/Δure; Fig. 7B) showed comparable survival plots. Animals infected with the double mutant (Δugh/Δure) consistently showed the highest percent survival (85–90%) compared to the single gene knock-out strains (Fig. 7A). Mice challenged with either the Δure or Δugh/Δure strain revealed significantly higher survival at 30 days postchallenge than mice infected with the WT strain of C. posadasii. Particularly striking was the statistically significant difference between the percent survival of BALB/c mice challenged with the Δugh mutant (approx. 25%) compared to survival of animals infected with the Δugh/Δure strain (P =0.006).

Fig. 7.

Survival plots of BALB/c mice challenged by the intranasal route with equal numbers of spores isolated from the wild type, mutant strains with single or double gene deletions, or revertant strains (A, B). A statistically significant difference was shown between survival of mice challenged with the mutants (single gene and double gene deletions) and ΔughR/Δure revertant strain compared to mice infected with either the WT or ΔughR revertant strain (P values <0.05 are considered significant). (C) Plots of CFUs of WT and mutant strains detected in lung homogenates of infected BALB/c mice at 14 days postchallenge. A statistically significant difference exists between mice challenged with each of the mutant strains compared to the WT strain. The survival and CFU plots are representative of three separate experiments.

The CFUs in lung homogenates derived from BALB/c mice infected with the WT or mutant strains of C. posadasii were determined at 14 days postchallenge (Fig. 7C). A significantly higher fungal burden in lungs of mice challenged with the Δugh strain (median = 4.39 [log10]) was observed compared to animals inoculated with spores of the Δugh/Δure strain (median = 2.06; P =0.004). These results correlated with the consistently observed difference in survival between the same two groups of mice (c.f. Fig. 7A). Mice challenged with strains carrying either the single or double mutations revealed significantly lower CFUs than animals challenged with the WT isolate (P <0.01; Fig. 7C). A discrepancy was apparent between the survival curves of mice infected with the WT or Δugh strain at 14 days postchallenge versus the fungal burden detected in their lungs. We suggest that the lower CFUs in lungs of mice infected with the Δugh mutant (approx. 3 log difference compared to the WT strain) was influenced by the persistently higher extracellular ammonia concentration at sites of infection (c.f., Fig. 5). High ammonia concentration localized at infection sites may have impeded but not inhibited growth and reproduction of the Δugh mutant while simultaneously compromising the cell mediated immune response to Coccidioides. The CFUs in lungs of mice inoculated with each of the revertant strains (ΔughR and ΔughR/Δure) were comparable to the fungal burden observed in mice challenged with the WT or Δure strain, respectively (data not shown).

2.7. Comparative histopathology

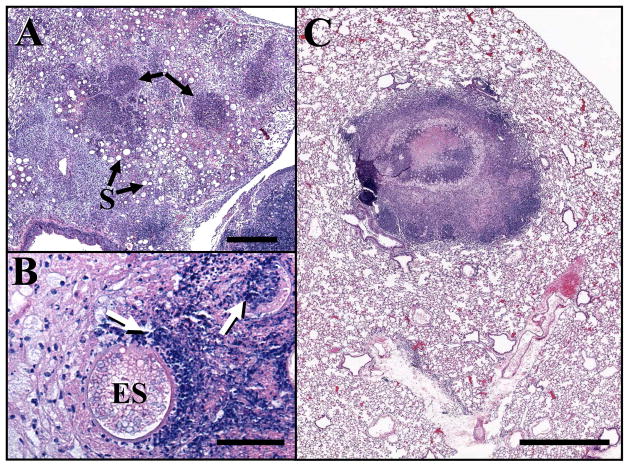

Paraffin sections of Coccidioides infected lungs obtained from BALB/c mice inoculated with 45 viable spores of either the Δugh mutant (Fig. 8A,B) or Δugh/Δure strain (Fig. 8C) and sacrificed at 30 days postchallenge revealed striking differences in histopathology. Lungs from mice inoculated with the Δugh mutant show high numbers of spherules in early stages of development prior to endosporulation (S in Fig. 8A). Several dense concentrations of stained host tissue are also visible (arrows in Fig. 8A). When viewed at higher magnification (Fig. 8B) it is evident that these densely stained regions are sites of concentrated inflammatory cells juxtaposed to mature spherules (ES) which had ruptured and released their contents. Inflammatory cells appear to have converged to the site of rupture and in some cases are visible within the spherule matrix (arrows in Fig. 8B). In contrast, the hstopathology of a representative lung section from a mouse challenged with the Δugh/Δure strain in Fig. 8C shows a well organized granuloma which has contained the fungal infection and is surrounded by healthy host tissue. The representative images in Fig. 8 correlate well with the differences in survival and retention of fungal burden observed between mice challenged with the Δugh mutant versus the Δugh/Δure strain. The histopathology of lungs infected with the Δure mutant was previously reported [10], and although well differentiated granulomas were also observed in this case the fungal infection did not appear to be contained to the extent shown in Fig. 8C. The histopathology of lungs infected with the ΔughR/Δure revertant strain was comparable to that of the Δure mutant, and the ΔughR revertant showed multiple pulmonary abscesses which are typical of mice infected with the WT stain (not shown).

Fig. 8.

Histopathology of the lungs of BALB/c mice challenged intranasally with spores of the Δugh mutant (A, B) versus the double gene deletion strain (Δugh/Δure) (C). Arrows in (A) and (B) locate dense clusters of inflammatory cells associated with mature spherules which had ruptured and released their contents. The sectioned lung in (C) shows a large, well differentiated granuloma surrounded by normal tissue. S, spherules in stages of development prior to endosporulation; ES, endosporulating spherules. Bars in (A–C) represent 0.5 mm, 60 μm and 2 mm, respectively.

3. Discussion

Combined results of our microscopic, biochemical and genetic studies of Coccidioides parasitic cell differentiation suggest that upon rupture of mature spherules endospores are released in an alkaline matrix. Furthermore, we have presented data indicating that the alkalinity is due to the presence of concentrated NH3/NH4+ in the spherule exudate which is exposed to the host during endosporulation. Several sets of experimental results reported in earlier studies support these conclusions. Direct light-microscopic examinations of cultured parasitic cells using a fluorescent pH indicator dye have revealed that the material released from endosporulating spherules is distinctly alkaline [12]. The peak of extracellular ammonia detected in media contained in wells of plate cultures supporting growth of near-synchronized stages of first generation parasitic cell development has been shown to be correlated with spherule rupture and endospore release. The histopathology of lungs of BALB/c mice infected with C. posadasii at 14 days after challenge revealed abscesses that contain large numbers of spherules, many of which are in the endosporulation stage of differentiation. Direct measurements of the internal pH of these lung abscesses immediately after the mice were sacrificed have recorded pH values in the alkaline range [10]. We have provided evidence that enzymatically active urease present in the spherule exudate contributes to its alkalinity due to hydrolysis of extracellular urea. Results of immunoelectron microscopy have demonstrated that urease protein is present in the spherule matrix released upon rupture of the parasitic cells, and we have argued that during spherule maturation in vivo extracellular urea is present at sites of lung infection and is derived from both the fungal pathogen and host [10]. A genetically-engineered strain of C. posadasii in which the URE gene was disrupted showed a marked decrease in ammonia concentration in supernatants of the parasitic phase culture medium. BALB/c mice challenged with the Δure strain showed a significant increase in survival and improved clearance of the pathogen from lung tissue compared to mice infected with the parental strain [10]. These latter results suggest that enzymatically-active urease and the detection of extracelluar ammonia during the parasitic cycle of Coccidioides are linked and contribute to the virulence of this fungal pathogen.

We have proposed that the presence of extracellular ammonia at sites of infection compromises cellular defenses of the host and contributes to survival of the pathogen during its critical reproductive stage. Inflammatory lesions in Coccidioides infected lungs of BALB/c mice are typically visible at 6 to 8 days postchallenge. Neutrophils are the major host defense cells which respond to this stage of symptomatic disease in the murine host [28]. Early innate immune cell response to a microbial insult generally plays an important role in signaling the recruitment of other defense cells [20]. In the case of coccidioidal infections in mice, however, there appears to be a delay in recruitment and expansion of the neutrophil population until the first generation spherules have ruptured and released their contents [28, 29]. Arthrocondia inhaled by the host germinate to give rise to first generation spherules which upon completion of their isotropic growth phase are too large to be engulfed by phagocytes. Histopathological evidence suggests that prior to endosporulation these first generation parasitic cells induce minimal host defense cell response. This stage of host-pathogen interaction is followed by a striking chemotaxis-like convergence of neutrophils to mature spherules that have ruptured and released their contents. However, it is evident at least in BALB/c mice that targeting of these phagocytic cells to infection sites is largely ineffective in clearance of the pathogen. In part, this may be due to the high reproductive capacity of Coccidioides during the endosporulation phase which overwhelms host defenses of this inbred mouse [26]. However, in vitro studies have shown that only 20–30% of endospores ingested by neutrophils are killed [30]. Degenerative neutrophils (swollen, karyolitic nuclei) are commonly associated with a toxic environment induced by microbial infections. Exposure of neutrophils to ammonia is known to impair phagocytosis and degranulation and induce spontaneous production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which results in oxidative stress at infection sites and collateral damage to host tissue [31]. Neutrophils incubated ex vivo with 75 μM ammonia were shown to swell and have reduced capacity to engulf opsonized Escherichia coli [32]. We have reported here that a greater than 2-fold higher concentration of ammonia was detected in supernatants of cultures that supported growth of endosporulating spherules of the wild type strain of C. posadasii. The association between neutrophils and ammonia may result in a paradoxical role for the innate immune cells in which aberrant activation contributes to inflammation and host tissue damage combined with impaired microbicidal capacity which may predispose to further infection [33].

Our current study was prompted by the possibility that urease activity is not the only source of extracellular ammonia detected during endosporulation. Comparative transcriptomic analyses of the cultured saprobic and parasitic phases were used to search for candidate gene products associated with metabolic pathways that yield ammonia [3]. We found 11 genes that were up-regulated in the parasitic phase, appeared to be under positive selection, and encoded products that are likely to be related to adaptation to the physical and biological environment. The ureidoglycolate hydrolase gene (UGH) was selected for further examination because of its association with a terminal step of allantoin catabolism which is conserved in fungi and results in ammonia production. It is reasonable to assume that Ugh hydrolysis of ureidoglycolate during growth of Coccidioides contributes to nitrogen reycling [19], but it is also possible that this biochemical pathway functions as a mechanism to expel excess nitrogen. A BLAST search for Ugh homologs indicated that Ugh is conserved amongst filamentous fungi, yeast and bacteria. Quantitative real-time PCR confirmed that expression of UGH is significantly up-regulated during spherule maturation and endospore release. Deletion of the UGH gene was successfully performed using both the wild type (WT) isolate of C. posadasii and previously reported Δure mutant as parental strains. The parasitic phase of the double mutant (Δugh/Δure) revealed in vitro growth and endosporulation comparable to the wild type strain, but revealed a significant reduction of extracellular ammonia in the culture media. The WT phenotype was restored when the UGH gene was reconstituted in the ΔughR/Δure revertant strain. A surprising outcome of these in vitro studies was the high level of extracellular ammonia produced by the Δugh strain during spherule maturation and the persistent high level of ammonia detected in the culture medium during early development of second generation spherules. We considered the possibility that URE expression was elevated during allantoin catabolism in the mutant strain as a compensation for the loss of Ugh activity, but this was not the case. We cannot rule out the possibility of post-tanscriptional up-regulation of urease synthesis and enzymatic activity. Another possibility is that that allantoicase, the second enzyme in the allantoin degradation pathway that hydrolyzes allantoate to NH3/NH4+, CO2 and ureidoglycolate is further up-regulated in the Δugh mutant [20]. Alternatively, a separate metabolic pathway may be influenced by deletion of UGH, a possibility that we can be explored by comparative transcriptomics of the Δugh and WT strains.

The significant reduction of extracellular ammonia detected in the culture media of the Δugh/Δure mutant compared to the WT and Δugh strains correlated with results of comparative virulence studies conducted with BALB/c mice. Approximately 90% of the animals challenged intranasally with the double gene-depletion strain survived and the histopathology of their lungs showed well differentiated granulomas that had contained the pathogen. In sharp contrast, only 25% of the mice infected with the Δugh mutant survived to 30 days postchallenge and all retained a high fungal burden in their lungs. In addition, the histopathology of the lungs of the latter group of mice showed extensive host tissue damage associated with regions of dense neutrophil accumulation surrounding spherules which had ruptured and released their contents. The results of these animal studies provide additional evidence that the alkaline microenvironment of C. posadasii compromises host defenses and contributes to the survival of the fungal pathogen.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Fungal strains, growth conditions and in vitro determination of extracellular NH3/NH4+ concentrations

The wild type (WT) isolate of C. posadasii C735 employed in this study was obtained from a patient with disseminated coccidioidomycosis and used previously as the parental strain for disruption of the urease (URE) gene [10]. Transformation was conducted with the hygromycin resistance gene (HPH) and transformants were selected for their ability to grow on hygromycin B. Both the WT isolate and urease mutant (Δure) were genetically engineered in the study reported here to generate mutants which lacked the UGH gene (Δugh and Δugh/Δure strains, respectively). Each was cultured under separate growth conditions for production of the saprobic (mycelial) and parasitic (spherule-endospore) phases. Spores (arthroconidia) isolated from mycelia grown on GYE agar plates (1% glucose, 0.5% yeast extract, 1.5% agar) at 30°C for 4 to 6 weeks were used to challenge mice for survival and fungal burden studies as described below. Spores were also used to inoculate a defined, glucose/salts liquid medium[34] for growth, light-microscopic examination, and isolation of different developmental stages of first generation parasitic cells (presegmented spherules, segmented spherules, and mature spherules in the process of endosporulation) as previously reported [8, 10]. Ammonium acetate (16.0 mM) was the sole nitrogen source added to this parasitic phase growth medium. The liquid cultures were incubated in 250 ml Erlenmeyer flasks at 39°C in a CO2 shaker incubator (140 rpm) in the presence of 20% CO2.

Extracellular ammonia concentrations during first generation spherule-endospore development were recorded during growth of the WT and mutant strains in RPMI 1640 medium lacking exogenous urea as previously described [10]. The culture medium was contained in 24-well, flat bottom, polystyrene tissue culture plates (1.0 ml/well). Each well was inoculated with 107 viable spores and the plates were placed in a CO2 incubator under the same growth conditions for growth of the parasitic phase as described above. Aliquots (50 μl) of the culture medium after centrifugation were sampled at different stages of parasitic cell development (incubation times between 24 and 156 hours) and analyzed by the Berthelot reaction for measurement of extracellular NH3/NH4+ concentrations as previously described [10, 13].

4.2. UGH isolation and quantitative real-time PCR analysis of gene expression

The C. posadasii C735 genome was originally sequenced by The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR; now the J. Craig Venter Institute) at 8X coverage and assembled into 58 contigs that totaled 27 Mb [35]. Computational analysis of the annotated genome sequence was conducted with the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) [36]. Sequence alignments were performed using the translated sequences of the contigs and the nonredundant protein database available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). A putative Coccidioides homolog of ureidoglycolate hydrolase was first identified by this method (gene CIMG_02178) [35]. Based on the reported UGH genomic and translated sequence of C. posadasii C735 (GenBank accession no. EER28584), PCR primers were synthesized to amplify a 3.2-kb genomic DNA fragment that contained the UGH gene. The nucleotide sequences of the primer pair used for amplification of this genomic fragment was as follows: forward 5′-TCATTTGAATTGCGTGAAGTTTC-3′, and reverse 5′-AATGCATTGATAACTA TTCTCGCTCA-3. The 3.2-kb amplicon was sequenced, aligned with the reported genomic sequence for accuracy, and used to generate the UGH deletion and revertant constructs as described below. The translated sequence included an 804-bp coding region of UGH flanked by 1,097-bp and 1,109-bp 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs).

Comparative transcriptomics was employed to determine gene expression differences between the saprobic and parasitic growth phases of this fungal pathogen [3, 35]. Of the 9,910 predicted genes of Coccidioides, 1,880 were reported to be up-regulated during the parasitic cycle. Expression of the UGH gene of C. posadasii was reported to be up-regulated during parasitic cell maturation in vitro compared to expression of UGH during growth of the saprobic phase [3]. To confirm this observation we examined expression of UGH during first generation spherule differentiation by quantitative real time (QRT)-PCR analysis. Total RNA was isolated from parasitic cells using a Qiagen RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen; Valencia CA). The spherule-endospore phase was cultured in RPMI 1640 as described above and parasitic cells were harvested after 72, 96 and 120–132 hours of incubation. Cultured parasitic cells of C. posadasii C735 at each of these incubation times showed near-synchronous development as pre-segmented, segmented or endosporulating spherules, respectively[8]. These cell-types were separately isolated and disrupted using a bead mill (Mini-Beadbeater, Biospec Products, Bartlesville, OK). Total RNA (1 μg) obtained from each sample was treated with DNAase I and cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). QRT-PCR was conducted in a Fast Real-Time PCR system (ABI Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using SYBR green as recommended by the manufacturer. The primer pair used for analysis of UGH gene expression was as follows: forward 5′-TCGCTACCATACGGG ATCCT-3′, and reverse 5′-CTCG CCCAAGACCACCAT-3′ which amplified a 105-bp product. The primer pair used for analysis of expression of the urease gene (URE) of C. posadasii C735 was as follows: forward 5′-ATGGTGTCACCCCCAACATG-3′, and reverse 5′-CGACCTGCTGTGGGCATATA-3′, which amplified a 120-bp product. Each reaction was normalized to expression of the constitutive glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene of the same strain of C. posadasii (GenBank accession no. AF188134) as previously reported [37] using the following primer pair: forward 5′-GGATGCTCTTGTTTCCT CCGA-3′, and reverse 5′-CCAAGCAAC GAGC TTGATGAA-3′, which amplified a 106-bp product. The data are presented as the ratio of the amount of the UGH or URE gene transcript to the amount of the GAPDH transcript in each sample. The QRT-PCR assays were performed in triplicate.

4.3. Deletion of UGH and generation of the revertant strains

A pΔugh plasmid construct was employed as a vector to delete the UGH gene by a replacement strategy [38]. The plasmid construct was designed using a 4.6-kb fragment of pAN8.1 (GenBank accession no. Z32751) which contained the phleomycin resistance gene (BLE) [39]. This same construct was used to transform both the WT and Δure parental strains for generation of the mutant genotypes. Expression of the BLE gene is driven by the Aspergillus nidulans promoter (pGPDA) and terminated by the A. nidulans terminator (tTRPC) [40]. Synthesized forward and reverse PCR primers (Table 2; forward/reverse primers a, b) were used to amplify a 1097-bp 5′-UTR fragment of UGH (Fig. 3A), which was then cloned into pAN8.1 at EcoRI and PstI restriction sites upstream of the GPDA promoter using an In-Fusion Advantage PCR Cloning Kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). A second forward/reverse primer pair (Table 2; c, d) with engineered NarI and NdeI sites, respectively, was used to amplify an 1109-bp 3′-UTR fragment of UGH, which was also cloned into pAN8.1 at corresponding restriction sites downstream of the TRPC terminator. The resulting plasmid construct was digested with EcoRI and NdeI and employed to delete the UGH gene by replacement (Fig. 3A). The transformation procedure was conducted as previously reported [25]. Putative Δugh a Δugh/ nd Δure transformants were selected on GYE agar plates supplemented with 5 μg/ml of phleomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Subsequent confirmation of the isolation of UGH gene-targeted deletion strains was performed by PCR screens and Southern hybridization as reported[24]. Three sets of PCR primers (Table 2; forward/reverse primers e/f, g/h, and i/j; see Fig. 3A) were used to screen the genomic DNA for putative transformants. Southern hybridization was conducted with nucleotide probes derived from UGH (Pb1) and the BLE gene (Pb2) (Fig. 3B). The Pb1 probe consisted of a 611-bp PCR product generated using a forward primer (5′-ATCAGCGGCTACCAATAATGCTT-3′) and reverse primer (5′-CTATGCAGAAC TGCCATTGGA-3′) in the presence of genomic DNA of each parental strain. The Pb2 gene probe consisted of a 393-bp PCR product generated by use of a forward primer (5′-ATGGCCAAGTTGACCAGTGCC-3′) and reverse primer (5′-TGCTCCTCGGCCACGAAGT-3′) in the presence of pAN8.1 plasmid template DNA. Southern hybridization was conducted with genomic DNA isolated from the parental and mutant stains separately digested with either SpeI or NdeI.

TABLE 2.

PCR primers used to screen transformants for UGH gene deletion and reconstitution

| Primer (F/R)a | Nucleotide sequenceb | Sequence origin | Size/use of PCR product |

|---|---|---|---|

| a (F) | 5′-CCATGATTACGAATTCTTCGGTGCATGTATGTGATT-3′ | UGH | 1097 bp; construct |

| b (R) | 5′-CAGTGTCGAAAGATCTGCAGGCAGTTCTCGAGGGAATTAGT-3′ | UGH | UGH KO |

| c (F) | 5′-AATGGCGCCAATTAACGCAAATGATAA-3′ | UGH | 1109 bp; construct |

| d (R) | 5′-AATCATATGCAGAACTTGGGATGGTT-3′ | UGH | UGH KO |

| e (F) | 5′-CCTATGGAACAGTGATCTCTCC-3′ | UGH | 563 bp; screen |

| f (R) | 5′-ATGTCCCGGTTGCATACGTAATT-3′ | UGH | UGH KO |

| g (F) | 5′-CCATCATTTGAATTGCGTGAAGTT-3′ | UGH | 1823 bp; screen |

| h (R) | 5′-CCTCAGATTCATGTTCATTCCATT-3′ | pAN8.1 | UGH KO |

| i (F) | 5′-GGTATACAATAGTAACCATGCATG-3′ | pAN8.1 | 1733 bp; screen |

| j (R) | 5′-GATGTCATTCGCAACCTAGTCAA-3′ | UGH | UGH KO |

| k (F) | 5′-ACTTGAAGTAATCTCTGCAGCAGCTGGTGCTGGACAACAG-3′ | UGH | 1901 bp; construct |

| l (R) | 5′-CAGTGTCGAAAGATCTGCAGTGAATCAGAGCCTTGCCCGGCTT-3′ | UGH | ΔughR revertant |

| m (F) | 5′-AATCCTTCTTTCTAGAATTCATGGCTTTCACCACCCCAAT-3′ | UGH | 1109 bp; construct |

| n (R) | 5′-TGAGAGTGCACCATATGAGAACTTGGGATGGTTGACCAGAT-3′ | UGH | ΔughR revertant |

| o (F) | 5′-ATGGCCAAGTTGACCAGTGCC-3′ | pAN9.1 | 393 bp; screen |

| p (R) | 5′-TGCTCCTCGGCCACGAAGT-3′ | pAN9.1 | ΔughR revertant |

| q (F) | 5′-TTCGTGGTCGTCTCGTACTCC-3′ | pAN9.1 | 2496 bp; screen |

| j (R) | 5′-GATGTCATTCGCAACCTAGTCAA-3′ | UGH | ΔughR revertant |

F is forward primer, and R is reverse primer.

In order to restore the functional UGH gene to both the Δugh and Δugh/Δure mutants a selectable marker distinct from phleomycin and hygromycin B resistance was necessary for design of a plasmid construct which could be employed to identify revertants. The NAT1 gene product, nourseothricin acetyltransferase (GenBank accession no. AY483215) confers resistance to the aminoglycoside antibiotic nourseothricin [41]. Fungal transformants with resistance to nourseothricin show no cross-resistance to either hygromycin B or phleomycin (http://www.fgsc.net/fgn53/kuck/fgn53kuck.htm). The NAT1 gene, contained in plasmid pCH233 [42], has a coding sequence of 573 bp which translates 191 amino acids. The NAT1 gene was PCR amplified using the following primer pair: forward, 5-ACTCGCCCAACATGTC TATG-3′, and reverse, 5′-GGCCTTCACAAATTATGGACA-3′. The 605-bp amplicon is flanked by single NcoI and RsrII restriction sites which were used to insert the NAT1 gene into the pAN8.1 plasmid. This modified plasmid is referred to here as pAN9.1 and is driven and terminated by the same promoter and terminator as in pAN8.1. The In-Fusion Advantage PCR Cloning Kit (Clontech) cited above was used to generate the revertant construct. A primer pair (Table 2; primers k, l) used to amplify a 1901-bp genomic fragment which included the UGH gene plus its 5′-UTR was inserted into the PstI site of pAN9.1 upstream of the GPDA promoter. A second primer pair (Table 2; primers m, n) was used to clone a second fragment (1109 bp) into pAN9-1 between XbaI and NdeI restriction sites downstream of the TRPC terminator. The plasmid construct was linearized with NdeI and used for transformation of the two mutant strains as described above. Putative transformants were selected on GYE agar plates supplemented with 100 μg/ml of nourseothricin (Werner BioAgents). Three sets of PCR primer pairs (Table 2; forward/reverse primers g/h, o/p and q/j) were used to PCR screen putative transformants with the restored, wild type UGH gene. Total genomic DNA isolated from selected transformants was digested with SpeI and NheI and hybridized with probes Pb1 and Pb3. The latter was derived from the NAT1 gene and consisted of a 695-bp PCR product generated using a forward primer (5′-GCTTGAGCAGACATCACCATG-3′) and reverse primer (5′-GTTAAGTGGA TCTCAAGCTCCT-3′) in the presence of pAN9.1 template DNA.

4.4 Virulence studies

To compare the virulence of the parental, mutant and revertant strains, spores (45 viable cells) were isolated from GYE agar plate cultures of each strain grown for 30 days at 30°C, suspended in saline, and used to inoculate BALB/c mice (8-week-old females; 12 per group) by the intranasal route as reported [10, 43]. The survival plots of each group of mice examined over a 30-day period were subjected to Kalpan-Meier statistical analysis as previously described [44]. For comparison of fungal burden 10 separate BALB/c mice of each group were sacrificed at 14 days postchallenge. Lung homogenates were plated and colony forming units (CFUs) were determined as described [10]. The CFU counts are expressed on a log scale, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the median numbers as previously reported [10].

4.5. Histopathology

Separate groups of BALB/c mice inoculated intranasally with each of the mutant or revertant strains (3 animals per group) were sacrificed at 30 days postchallenge. Mice inoculated with the WT and ΔughR revertant strain were sacrificed at 14 days. Infected lungs were excised and prepared for histopathology examination as previously described [44]. Sections of paraffin embedded lung tissue were stained with hematoxylin and eosin by standard procedures and examined using a Leica DMI6000B light microscope equipped with a TurboScan stage (Objective Imaging, Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom). Images of infected lung tissue were acquired and analyzed using Surveyor software (Objective Imaging) as previously reported[45].

Acknowledgments

Support for this study was provided by Public Health Service grants AI071118 and AI070891 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health awarded to GTC. Additional support was provided by the Margaret Batts Tobin Foundation, San Antonio, TX.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fisher MC, Koenig GL, White TJ, Taylor JW. Molecular and phenotypic description of Coccidioides posadasii sp. nov. previously recognized as the non-California population of Coccidioides immitis. Mycologia. 2002;94:73–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ampel NM, Hector RF. Measuring cellular immunity in coccidioidomycosis: the time is now. Mycopathol. 2010;169:425–426. doi: 10.1007/s11046-010-9285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whiston E, Zhang Wise H, Sharpton TJ, Jui G, Cole GT, Taylor JW. Comparative transcriptomics of the saprobic and parasitic growth phases in Coccidioides spp. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowman BH, White TJ, Taylor JW. Human pathogeneic fungi and their close nonpathogenic relatives. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1996;6:89–96. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1996.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cole GT, Kirkland TN. Conidia of Coccidioides immitis: their significance in disease initiation. In: Cole GT, Hoch HC, editors. The Fungal Spore and Disease Initiation in Plants and Animals. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1991. pp. 403–443. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blundell GP, Castleberry MW, Lowe EP, Converse JL. The pathology of Coccidioides immitis in the Macaca mulatta. Am J Pathol. 1961;39:613–630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Converse JL, Lowe EP, Castleberry MW, Blundell GP, Besemer AR. Pathogenesis of Coccidioides immitis in monkeys. J Bacteriol. 1962;83:871–878. doi: 10.1128/jb.83.4.871-878.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hung C-Y, Yu J-J, Lehmann PF, Cole GT. Cloning and expression of the gene which encodes a tube precipitin antigen and wall-associated β-glucosidase of Coccidioides immitis. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2211–2222. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2211-2222.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cole GT, Xue J, Seshan KR, Borra P, Borra R, Tarcha E, et al. Virulence mechanisms of Coccidioides. In: Heitman J, Filler S, Edwards JE, Mitchell AP, editors. Molecular Principles of Fungal Pathogenesis. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2006. pp. 363–391. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirbod-Donovan F, Schaller R, Hung C-Y, Xue J, Reichard U, Cole GT. Urease produced by Coccidioides posadasii contributes to the virulence of this respiratory pathogen. Infect Immun. 2006;74:504–515. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.504-515.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bump WA. Observations on growth of Coccidioides immitis. J Infect Dis. 1925;36:561–565. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole GT. Fungal Pathogenesis. In: Anaissie E, McGinnis MR, Pfaller MA, editors. Clinical Mycology. Churchill Livingstone; New York: 2003. pp. 20–45. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirbod F, Schaller RA, Cole GT. Purification and characterization of urease isolated from the pathogenic fungus Coccidioides immitis. Med Mycol. 2002;40:35–44. doi: 10.1080/mmy.40.1.35.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benoit SL, Maier RJ. Mua (HP0868) is a nickel-binding protein that modulates urease activity in Helicobacter pylori. MBio. 2011;2:e00039–00011. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00039-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armbruster CE, Mobley HL. Merging mythology and morphology: the multifaceted lifestyle of Proteus mirabilis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:743–754. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konieczna I, Zarnowiec P, Kwinkowski M, Kolesinska B, Fraczyk J, Kaminski Z, et al. Bacterial urease and its role in long-lasting human diseases. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2012;13:789–806. doi: 10.2174/138920312804871094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osterholzer JJ, Surana R, Milam JE, Montano GT, Chen GH, Sonstein J, et al. Cryptococcal urease promotes the accumulation of immature dendritic cells and a non-protective T2 immune response within the lung. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:932–943. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vogels GD, Van der Drift C. Degradation of purines and pyrimidines by microorganisms. Bacteriol Rev. 1976;40:403–468. doi: 10.1128/br.40.2.403-468.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Serventi F, Ramazzina I, Lamberto I, Puggioni V, Gatti R, Percudani R. Chemical basis of nitrogen recovery through the ureide pathway: formation and hydrolysis of S-ureidoglycine in plants and bacteria. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5:203–214. doi: 10.1021/cb900248n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Werner AK, Romeis T, Witte CP. Ureide catabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana and Escherichia coli. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:19–21. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin I, Percudani R, Rhee S. Structural and functional insights into (S)-ureidoglycine aminohydrolase, key enzyme of purine catabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:18796–18805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.331819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;24:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reichard U, Hung C-Y, Thomas PW, Cole GT. Disruption of the gene which encodes a serodiagnostic antigen and chitinase of the human fungal pathogen Coccidioides immitis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5830–5838. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.10.5830-5838.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hung C-Y, Seshan KR, Yu J-J, Schaller R, Xue J, Basrur V, et al. A metalloproteinase of Coccidioides posadasii contributes to evasion of host detection. Infect Immun. 2005;73:6689–6703. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6689-6703.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hung C-Y, Wise HZ, Cole GT. Gene disruption in Coccidioides using hygromycin or phleomycin resistance markers. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;845:131–147. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-539-8_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirkland TN, Fierer J. Inbred mouse strains differ in resistance to lethal Coccidioides immitis infection. Infect Immun. 1983;40:912–916. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.3.912-916.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shubitz L, Peng T, Perrill R, Simons J, Orsborn K, Galgiani JN. Protection of mice against Coccidioides immitis intranasal infection by vaccination with recombinant antigen 2/PRA. Infect Immun. 2002;70:3287–3289. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.6.3287-3289.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hung C-Y, Gonzalez A, Wuthrich M, Klein BS, Cole GT. Vaccine immunity to coccidioidomycosis occurs by early activation of three signal pathways of T helper cell response (Th1, Th2, and Th17) Infect Immun. 2011;79:4511–4522. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05726-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cole GT, Hurtgen BJ, Hung C-Y. Progress towrd a human vaccine against coccidioidomycosis. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2012;6:235–244. doi: 10.1007/s12281-012-0105-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drutz DJ, Huppert M. Coccidioidomycosis: factors affecting the host-parasite interaction. J Infect Dis. 1983;147:372–390. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.3.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shawcross DL, Wright GA, Stadlbauer V, Hodges SJ, Davies NA, Wheeler-Jones C, et al. Ammonia impairs neutrophil phagocytic function in liver disease. Hepatology. 2008;48:1202–1212. doi: 10.1002/hep.22474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shawcross DL, Shabbir SS, Taylor NJ, Hughes RD. Ammonia and the neutrophil in the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2010;51:1062–1069. doi: 10.1002/hep.23367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tranah TH, Vijay GK, Ryan JM, Shawcross DL. Systemic inflammation and ammonia in hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis. 2013;28:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s11011-012-9370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levine HB. Purification of the spherule-endospore phase of Coccidioides immitis. Sabouraudia. 1961;1:112–115. doi: 10.1080/00362176285190231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharpton TJ, Stajich JE, Rounsley SD, Gardner MJ, Wortman JR, Jordar VS, et al. Comparative genomic analyses of the human fungal pathogens Coccidioides and their relatives. Genome Res. 2009;19:1722–1731. doi: 10.1101/gr.087551.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acid Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delgado N, Xue J, Yu J-J, Hung C-Y, Cole GT. A recombinant β-1,3-glucanosyltransferase homolog of Coccidioides posadasii protects mice against coccidioidomycosis. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3010–3019. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3010-3019.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.d’Enfert C, Weidner G, Mol PC, Brakhage AA. Transformation systems of Aspergillus fumigatus: New tools to investigate fungal virulence. Contrib Microbiol. 1999;2:149–166. doi: 10.1159/000060292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Punt PJ, Oliver RP, Dingemanse MA, Pouwels PH, van den Hondel CA. Transformation of Aspergillus based on the hygromycin B resistance marker from Escherichia coli. Gene. 1987;56:117–124. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Punt PJ, Dingemanse MA, Kuyvenhoven A, Soede RD, Pouwels PH, van den Hondel CA. Functional elements in the promoter region of the Aspergillus nidulans gpdA gene encoding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Gene. 1990;93:101–109. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90142-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alshahni MM, Makimura K, Yamada T, Takatori K, Sawada T. Nourseothricin acetyltransferase: a new dominant selectable marker for the dermatophyte Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Med Mycol. 2010;48:665–668. doi: 10.3109/13693780903330555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Idnurm A, Reedy JL, Nussbaum JC, Heitman J. Cryptococcus neoformans virulence gene discovery through insertional mutagenesis. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3:420–429. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.2.420-429.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muhammed M, Feldmesser M, Shubitz LF, Lionakis MS, Sil A, Wang Y, et al. Mouse models for the study of fungal pneumonia: a collection of detailed experimental protocols for the study of Coccidioides, Cryptococcus, Fusarium, Histoplasma and combined infection due to Aspergillus-Rhizopus. Virulence. 2012;3:329–338. doi: 10.4161/viru.20142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xue J, Chen X, Selby D, Hung C-Y, Yu J-J, Cole GT. A genetically engineered live attenuated vaccine of Coccidioides posadasii protects BALB/c mice against coccidioidomycosis. Infect Immun. 2009;77:3196–3208. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00459-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hurtgen BJ, Hung C-Y, Ostroff GR, Levitz SM, Cole GT. Construction and evaluation of a novel recombinant T cell epitope-based vaccine against coccidioidomycosis. Infect Immun. 2012;80:3960–3974. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00566-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]