Background: Lipoprotein lipase (LpL) is rate-limiting for plasma triglyceride lipolysis, but its importance in adipose development is uncertain.

Results: Adipocyte LpL knock-out affected brown but not white fat composition. White fat was reduced when muscle LpL expression was increased.

Conclusion: LpL distribution and adipose metabolism affect adipogenesis.

Significance: All fat depots are not equally dependent on triglyceride uptake.

Keywords: Adipocyte, Fatty Acid, Lipids, Macrophages, Obesity, Hypertriglyceridemia

Abstract

Adipose fat storage is thought to require uptake of circulating triglyceride (TG)-derived fatty acids via lipoprotein lipase (LpL). To determine how LpL affects the biology of adipose tissue, we created adipose-specific LpL knock-out (ATLO) mice, and we compared them with whole body LpL knock-out mice rescued with muscle LpL expression (MCK/L0) and wild type (WT) mice. ATLO LpL mRNA and activity were reduced, respectively, 75 and 70% in gonadal adipose tissue (GAT), 90 and 80% in subcutaneous tissue, and 84 and 85% in brown adipose tissue (BAT). ATLO mice had increased plasma TG levels associated with reduced chylomicron TG uptake into BAT and lung. ATLO BAT, but not GAT, had altered TG composition. GAT from MCK/L0 was smaller and contained less polyunsaturated fatty acids in TG, although GAT from ATLO was normal unless LpL was overexpressed in muscle. High fat diet feeding led to less adipose in MCK/L0 mice but TG acyl composition in subcutaneous tissue and BAT reverted to that of WT. Therefore, adipocyte LpL in BAT modulates plasma lipoprotein clearance, and the greater metabolic activity of this depot makes its lipid composition more dependent on LpL-mediated uptake. Loss of adipose LpL reduces fat accumulation only if accompanied by greater LpL activity in muscle. These data support the role of LpL as the “gatekeeper” for tissue lipid distribution.

Introduction

Adipose triglyceride (TG)4 is thought to be predominantly acquired from circulating lipoproteins; de novo synthesis of fatty acids is normally a minor contributor to adipose TG and accounts for less than 25% of adipose TG in humans (1–3).

Dietary chylomicron TG and endogenously produced VLDL-TG require intravascular hydrolysis by lipoprotein lipase (LpL) to liberate free fatty acids (FFA), which are then acquired by adipocytes (4). Total body LpL knock-out leads to severe hypertriglyceridemia in humans (5). Newborn mice ingest a high fat milk diet, and total body LpL deficiency leads to neonatal death associated with hypoglycemia (6). This neonatal death is prevented by overexpressing LpL in skeletal muscle or liver (7).

Although LpL has been described as the gatekeeper for TG uptake and appears to distribute TG among tissues (8), humans with genetic defects in LpL and mice expressing LpL only in muscle (MCK/L0) have been reported to have normal body weight (9). In contrast, in the setting of leptin deficiency, MCK/L0 mice have reduced obesity (9). The source of adipose fatty acids in MCK/L0 mice is controversial and might either reflect de novo synthesis (9) or acquisition of fatty acids from other lipoproteins, perhaps due to the actions of endothelial lipase (10).

Adipose depots differ in function and metabolism (11). Metabolism of subcutaneous and intraperitoneal white adipose tissues (WATs) and their relationship to insulin sensitivity have been investigated in the most detail (12). Brown adipose tissue (BAT), which has recently been found in humans (13–15), is responsible for adaptive thermogenesis (15, 16) and has been proposed to be an important site of tissue TG clearance in rodents (16). In this study, we explored whether alterations in the ability of adipocytes to acquire lipoprotein-derived fatty acids affects adipose tissue development and gene expression. To do this we compared wild type (WT), MCK/L0, and mice that we created with adipocyte-specific loss of LpL expression (ATLO). ATLO mice were also bred with MCK/L0 mice to obtain mice with LpL overexpression in muscle coupled with deficiency in adipose (MCK/ATLO). Although all lines of mice had identical body weights, MCK/L0 and MCK/ATLO mice had reduced WAT, whereas ATLO did not. ATLO mice had reduced uptake of lipids into BAT and increased plasma TG levels. On chow, but not high fat diets (HFD), both ATLO and MCK/L0 BAT had reduced contents of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). Our data show that adipocyte LpL plays a more essential role in TG synthesis and composition in BAT than in WAT and that TG distribution is a critical regulator of gonadal adipose tissue (GAT) mass.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation of ATLO Mice

Mice with adipose tissue-specific deletion of LpL (ATLO) were generated by crossing Lplflox/flox mice, previously created in this laboratory (17), and Ap2-Cre mice (The Jackson Laboratory). The cross of Lplflox/flox mice with Ap2-cre mice generated Ap2-Cre/Lplflox/+. These mice were crossed again with Lplflox/flox to generate Ap2-Cre/Lplflox/flox (ATLO). Genotypes were determined by standard PCR on tail tip genomic DNA. The presence of the Ap2-Cre transgene was detected by primer sequences within the Cre recombinase region as follows: sense 5′-ATT TGC CTG CAT TAC CGG TC-3′ and antisense 5′-ATC AAC GTT TTG TTT TCG GA-3′. Floxed Lpl was also confirmed with primers that detect the second loxP within intron 1 as follows: sense 5′-CGG CTT AGC TCA GTA CTC AA-3′ and antisense 5′-TCT AGG CAG AGA GCA GGC AGA-3′. We also created ATLO mice with LpL overexpression in skeletal muscle by crossing the MCK-Lpl transgene onto the ATLO background. These mice are denoted MCK/ATLO.

Macrophage LpL Knock-out Mice

Adipose tissues from mice with specific deletion of LpL in macrophages were obtained by crossing Lplflox/+ mice with transgenic mice carrying Cre recombinase under the control of the lysozyme promoter (Lys-cre, The Jackson Laboratory). From the descendants, Lplflox/+/Lys-Cre mice were then crossed with Lplflox/+ to create the macrophage-specific LpL knockouts (ML0) (18).

Mouse Breeding and Husbandry

All procedures were in accordance with current National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the Columbia University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. MCK/L0 mice were bred and genotyped as described (19). All animals were housed under controlled temperature (23 °C) and lighting (12 h light, 06:00–18:00 h; 12 h dark, 18:00–06:00 h) with free access to water. Mice were fed a standard mouse chow (Purina) or a high fat diet (Research Diets, D12492) that contains 34.9% fat by weight, providing 60% of calories from fat. The composition of the diets is detailed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Fatty acid composition of the diet

| Chow diet | High fat diet | |

|---|---|---|

| % fat | ||

| Calories | 13.2 | 60 |

| Grams | 5 | 34.9 |

| Fatty acid profile per 100 g of fat | ||

| SFA | 18.6 | 32.0 |

| MUFAs | 19.8 | 35.9 |

| PUFAs | 61.6 | 32.0 |

Plasma Lipids and Glucose

Blood samples were obtained by retro-orbital bleeding after 4–6 h of fasting. Plasma total cholesterol (TC), TG, and FFA were determined enzymatically (Wako Chemicals). Glucose was measured in tail blood using a glucometer (One Touch Ultra; Lifescan).

Tissue Collection

Mice were anesthetized with isofluorane, and hearts were perfused with 10 ml of PBS or until the livers blanched. Tissues were rapidly removed and frozen in liquid nitrogen unless otherwise noted.

Peritoneal Macrophage Isolation

After peritoneal lavage with saline, the solution was centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min. Cells were resuspended in 1 ml of DMEM with 10% FBS and plated. After 3 h in a 37 °C incubator, nonadherent cells were washed away with PBS, and the adherent cells were scraped and frozen.

Separation of Adipocytes and Stromal Vascular Cells (SVC)

Isolation was performed as in Ref. 20. Briefly, gonadal fat pads were minced, placed in 5 volumes of HEPES-buffered DMEM supplemented with 10 mg/ml fatty acid-poor BSA, and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min. An LPS-depleted collagenase mixture (LiberaseTM, Roche Applied Science) at a concentration of 0.03 mg/ml and 50 units/ml DNase I (Sigma) was added to the tissue, and the samples were incubated at 37 °C in a shaking water bath for 45 min. Then, the samples were passed through a 250-μm nylon mesh (Sefar America Inc.). The suspension was centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min, and the pelleted cells were collected as the SVC. The floating cells were collected as the adipocytes. The adipocyte fraction was digested for 1 additional hour, washed, and centrifuged as above until no pellet was observed. The SVC were resuspended in erythrocyte lysis buffer (Biolegend) and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Afterward, these cells were pelleted, resuspended in PBS, and frozen.

Immunofluorescence and Colocalization

The colocalization of adipocyte LpL with CD11b-positive cells was examined by immunofluorescence similarly to the process previously described (21). In brief, 5-μm formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded mouse adipose sections were treated with a heat-induced antigen retriever (citrate buffer, Sigma) following the manufacturer's instructions. Subsequently, 4% horse serum (Sigma) was applied to the sections to block nonspecific background staining. Adipose sections were then incubated at 4 °C overnight with primary goat anti-LpL IgG (2.5 μg/ml, provided by Dr. Andre Bensadoun, Cornell University) and rat anti-CD11b IgG (1:200; AbD Serotec). A 1-h incubation with a mixture of the corresponding secondary antibodies Alexa 647 anti-goat IgG (1:200) and Alexa 488 anti-rat IgG (1:200) followed. Fluorescence was detected using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Nikon A1R MP) equipped with a ×60 oil immersion objective (numerical aperture 1.45). Excitation and emission wavelengths were as follows: Alexa 488, excitation 488 nm and emission 500–550 nm; Alexa 647, excitation 640 nm and emission 663–728 nm. Colocalization was quantified by a threshold-based overlap analysis, i.e. a binary test of whether the two signals occur in the same or in different regions, using ImageJ 1.41 (National Institutes of Health, rsb.info.nih.gov) (22). Each group consisted of four mice, and three to five regions were analyzed for each adipose sample. The colocalization of LpL with CD11b was expressed as the percentage of LpL-positive pixels that also had CD11b signal.

Gene Expression by Quantitative Real Time PCR

Excepting adipose, total RNA was obtained from tissues homogenized in TRIzol reagent. The PureLink RNA mini kit was used for the RNA purification. For adipose tissues, PureLink RNA mini kit was used in all the steps. The RNA was then reverse-transcribed by ThermoScript RT-PCR System (Invitrogen), and quantitative real time PCR was performed with Stratagene Mx3005 using SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems). 18 S rRNA was used as a housekeeping gene to normalize expression in all studies. All primer sequences are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

List of primers used for quantitative PCR

| Forward | Reverse | |

|---|---|---|

| 18 S rRNA | CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG | GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT |

| Angptl4 | GGAAAAGATGCACCCTTCAA | TGCTGGATCTTGCTGTTTTG |

| AOX | ATCACGGGCACTTATGC | TCTCACGGATAGGGACA |

| ATGL | CGCCTTGCTGAGAATCAGCA | AGTGAGTGGCTGGTGAAAGGT |

| DGAT1 | GTGCACAAGTGGTGCATCAG | CAGTGGGATCTGAGCCATCA |

| EL | CCTGCATACCTACACGCTGTC | GTCAATGTGACCCACAGGCA |

| FAS | CGTATATGTGAACAGCGC | AGGTCTCGGATGCCTA |

| HSL | ACACAAATCCCGCTATG | CTCGTTGCGTTTGTAGT |

| LpL | TCTGTACGGCACAGTGG | CCTCTCGATGACGAAGC |

| MCP1 | CCGGCCCTCCCTGGTCCAAA | GTAGAGCTCAGCGGGGGAGGG |

| SCD1 | GCGATACACTCTGGTGCTCA | CCCAGGGAAACCAGGATATT |

| SCD2 | ACAACTACCACCACGCCTTC | GCTTCTGGAACAGGAACTGC |

| PPARα | ACTACGGAGTTCACGCATGTG | TTGTCGTACACCAGCTTCAGC |

| PPARδ | AGATGGTGGCAGAGCTATGACC | TCTCCTCCTGTGGCTGTTCC |

| PPARγ1 | GAGTGTGACGACAAGATTTG | GGTGGGCCAGAATGGCATCT |

| PPARγ2 | GGTGGGCCAGAATGGCATCT | TCTGGGAGATTCTCCTGTTG |

LpL Activity Assay

Postheparin plasma and tissue LpL activity were determined as described in detail by Hocquette et al. (23). Postheparin plasma was obtained from fasted mice 5 min after tail vein injection of 100 units of heparin/kg body weight. To measure total lipase activity, tissues were homogenized and incubated with 10% Intralipid/[3H]TG emulsion as substrate and human serum as the source of apoCII (24). The contribution of hepatic lipase was determined by including 1 mm NaCl in the assay and was subtracted from the total lipase activity to estimate LpL. Activity was normalized to the WT mice.

Heparin releasable activity in adipose was measured following the method by Haugen et al. (25). Briefly, freshly isolated tissues were minced in Krebs-Ringer phosphate buffer and incubated for 45 min in a 37 °C water bath in the presence of 15 μg/ml heparin. After that, 100-μl aliquots of the buffer were used for the lipase assay with 100 μl of 10% Intralipid/[3H]TG emulsion for 45 min at 37 °C. Aliquoted human plasma was used for a standard curve in all the experiments.

Hepatic TG Secretion

To measure hepatic TG production rate, 4-h fasted mice were injected with 1 g/kg body weight tyloxapol in saline (26). Plasma samples were collected immediately prior to injection and at 1 and 6 h following injection. TG concentrations were determined enzymatically.

Chylomicron Uptake Study

The method described by Bharadwaj et al. (27) was followed. Briefly, tamoxifen-inducible LpL knock-out (LpLKO) mice were used to prepare the endogenously radiolabeled chylomicrons. Four-hour fasted LpLKO mice were gavaged with a mixture of [14C]TG, [3H]retinol ([3H]ROH) (PerkinElmer Life Sciences), and unlabeled all-trans-ROH (Sigma) in peanut oil. After 4–5 h, chylomicrons were obtained by ultracentrifugation of plasma at d = 1.006 g/ml. Endogenously radiolabeled chylomicrons were then injected into the tail vein. Blood was collected at 0.5, 5, and 15 min after injection. At 15 min, hearts were perfused with cold PBS. Tissues were harvested, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until further use. Radioactivity was determined in 10 μl of plasma and 100 μl of tissue homogenate.

Tissue Uptake of Glucose and Incorporation of Glucose into Lipids

Glucose uptake was assessed following the method in Liu et al. (28). Mice were intravenously administered 2-deoxy-d-[1-3H]glucose after 4 h of fasting. Blood was obtained at 2, 5, 15, 30, and 60 min after injection. At 60 min the heart was perfused with 10 ml of cold PBS, and tissues were harvested. Radioactivity was determined in 100 μl of homogenate and 10 μl of plasma and normalized to the area under the decay curve.

Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA)

Mice were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine and placed in a PIXImus II DEXA scanner (GE Lunar).

Lipid Extraction and Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS)

The lipidomic analysis was performed as in Clugston et al. (29). To assess the fatty acyl composition of adipose TG, ∼200 mg of adipose tissue was homogenized in 1 ml of PBS. After centrifugation to remove debris, the homogenate was transferred to a glass tube; 5 ml of 2:1 chloroform/methanol (v/v) was added, and the sample was vigorously mixed and centrifuged at 800 × g to separate phases. The chloroform phase was collected, evaporated under N2 to dryness, and reconstituted in 0.1 ml of chloroform. Lipid species were separated on a Whatman adsorption 60-Å silica gel TLC plate (20 × 20 cm) and visualized in an iodine chamber. The separated TGs were scraped and transferred to a glass tube with 1 ml of ethanolic KOH and an internal standard consisting of 2.5 μmol of heptadecanoic acid in 0.05 ml of ethanol. After incubation at 60 °C for 1 h, 0.5 ml of H2O and 0.4 ml of hexane were added and the phases separated by centrifugation. The nonsaponifiable lipids in the upper hexane phase were removed, and the pH of the lower phase was titrated with 1 n HCl to pH 2.5. The unesterified fatty acids were then extracted into hexane and analyzed by LC/MS. All analyses were carried out on a Waters Xevo TQ MS ACQUITY UPLC system (Waters).

Bone Marrow Transplant

The protocol was based on that of Han et al. (30). Recipient mice received water supplemented with 10 mg/liter neomycin (Sigma) 2 weeks before and after bone marrow transplantation. Eight-week-old male mice were lethally irradiated with 13 gray from a cesium source in 2 doses separated by 4 h. Bone marrow was collected from femurs and tibias of donor mice by flushing with sterile medium (RPMI 1640, 2% FBS, 5 units/ml heparin, 50 units/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin). Each recipient mouse was injected with 3–5 × 106 bone marrow cells. After 4 weeks, peripheral blood was collected from the tail vein for PCR to check donor bone marrow reconstitution. Once reconstitution was confirmed, recipient mice were kept on chow diet for 8 weeks to allow resident macrophage population turnover. Mice were then sacrificed, and organs were collected.

Adenovirus Amplification and Direct GAT Injection

The recombinant adenovirus expressing MCP1 was purchased from Vector Laboratories, propagated as described previously (31), and titrated with Adeno-X Rapid titer kit (Clontech) following the instructions of the manufacturer. Mouse GAT was surgically exposed, and adenoviral preparations containing 1·108 pfu were directly injected in each pad in three separated points. Incisions were closed and sutured, and mice were allowed to recover. After 10 days, the mice were sacrificed, and plasma and tissues were collected.

Statistics

Results are given as means ± S.E. Statistical significance was tested using two-tailed Student's t test. Statistical analysis was done using GraphPad Prism 5 software.

RESULTS

Characterization of ATLO Mice

The Lpl gene deletion was confirmed by PCR in adipose tissue by showing deletion of Lpl exon 1 (Fig. 1A). Hearts from cardiomyocyte-specific LpL knock-out mice (17) were used as a positive control. As a consequence of the deletion, ATLO mice had 75% reduction of Lpl mRNA in GAT, 90% reduction in subcutaneous adipose tissue (SCAT), and 84% reduction in BAT (Fig. 1B). Because the Ap2 promoter is also expressed in macrophages, we separated the SVC and adipocyte fraction from GAT. Not unexpectedly, there was a partial (∼74%) decrease in Lpl mRNA levels in the SVC fraction, although in the adipocyte fraction the decrease in mRNA was 82%. In contrast to adipose, there was no significant reduction in Lpl mRNA in peritoneal macrophages from ATLO mice (Fig. 1B). Confocal microscopy of GAT showed more colocalization of LpL with the macrophage marker Cd11b in ATLO than in WT mice. The quantification indicated that in WT mice 12.5 ± 1.3% of LpL colocalized with CD11b, and in ATLO the proportion increased to 34.0 ± 4.9% (p < 0.05; Fig. 1C). The other adipose depots did not show differences in the proportion of LpL colocalizing with CD11b.

FIGURE 1.

Characterization of ATLO mice. Ap2-cre mice were crossed with Lpl floxed mice. A, genotyping strategy. A PCR with two different reverse primers was used. In the absence of Cre recombinase, primers A and B generate a 700-bp PCR product, and primers A and C generate a 1925-bp product. In the presence of Cre recombinase, deletion of the first exon of Lpl results in a 400-bp PCR product. A representative gel of this PCR in adipose tissue is shown. Heart DNA obtained from a heart-specific LpL knock-out was used a positive control in the gel. B, Lpl mRNA analysis by quantitative PCR in GAT, SCAT, BAT, and SVC isolated from GAT. C, Immunofluorescence of LpL and CD11b in GAT and colocalization quantification in GAT, SCAT, and BAT. D, LpL activity was measured in homogenized whole tissues and in postheparin plasma using a radiolabeled triglyceride substrate. E, LpL activity and mRNA measured in lungs from WT, ATLO, and MCK/L0 mice. Mean ± S.E. is shown. PHP, postheparin plasma. Statistical significance: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

The decrease in Lpl mRNA in the adipose tissue translated into reduced activity. In ATLO mice, LpL activity was reduced by 70% in GAT, by 80% in SCAT, and by 85% in BAT (Fig. 1D). LpL activity in muscle and heart, the other main organs where LpL is abundantly expressed, was not changed. Not surprisingly, postheparin plasma LpL activity was also not significantly altered. However, Lpl mRNA and activity were reduced in the lung (Fig. 1E).

Phenotype of ATLO Mice on Chow and HFD

To determine the whole body effects of the loss of adipocyte LpL, we assessed the plasma lipid and glucose levels both in mice fed chow and HFD. We included the MCK/L0 mouse in this study to compare our data with a complete adipose LpL knock out (9). ATLO mice had elevated plasma TG on both chow and HFD feeding (Table 3), although TC and glucose levels were identical to those in WT mice. Consistent with previous findings (9), MCK/L0 mice had decreased levels of plasma TG and TC.

TABLE 3.

Plasma parameters in WT, ATLO, and MCK/L0 mice

The mean ± S.E. is shown. Comparisons of MCK/L0 or ATLO versus WT: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

| Chow diet |

High fat diet |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | ATLO | MCK/L0 | WT | ATLO | MCK/L0 | |

| TG (mg/dl) | 81 ± 9 | 143 ± 19* | 34 ± 3*** | 53 ± 4 | 116 ± 8*** | 55 ± 11 |

| TC (mg/dl) | 50 ± 2 | 48 ± 2 | 53 ± 2 | 175 ± 7 | 203 ± 5 | 123 ± 13** |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 150 ± 10 | 168 ± 9 | 179 ± 11 | 233 ± 13 | 217 ± 20 | 199 ± 15 |

| FFA (mmol/liter) | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.03** | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

ATLO, MCK/L0, and WT mice were kept on chow or on HFD starting at weaning, and their body weights were measured (Fig. 2A). Both males and females gained weight at the same rate as they aged. On the chow diet, ATLO mice showed no differences in the morphology of their adipose tissues, macro- or microscopically, whereas MCK/L0 mice had smaller GAT than the ATLO or the WT mice (Fig. 2B). No differences were observed in SCAT or BAT mass among the three genotypes when they were kept on chow diet (Fig. 2B). After 8 weeks on HFD, GAT mass increased in WT from 0.35 ± 0.04 g (p < 0.05) in chow to 1.9 ± 0.5 g and in ATLO from 0.28 ± 0.02 to 2.1 ± 0.1g (p < 0.001). But in MCK/L0, GAT only increased from 0.14 ± 0.01 to 0.25 ± 0.02 g (p < 0.001 versus chow and p < 0.001 versus WT HFD). Similarly, for HFD-fed WT and ATLO, the SCAT increased by ∼4-fold in WT and ATLO mice; in MCK/L0 mice, SCAT size did increase. Also after the HFD, the BAT enlarged in WT and ATLO mice but not in MCK/L0 (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Body weight and fat morphology in ATLO and MCK/L0 mice in chow and HFD. A, body weight was monitored on chow and high fat diet from weaning until 16 weeks of age. B, adipose tissue mass from WT, ATLO, and MCK/L0 mice on chow and on HFD. C, macroscopic and microscopic appearance of the adipose tissues on chow diet. D, percentage of body fat and lean mass in WT, ATLO, and MCK/L0 mice on chow and HFD. Representative DEXA scans are shown. E, liver TG levels in WT, ATLO, and MCK/L0 mice on chow and after HFD. Statistical significance: ATLO or MCK/L0 versus control: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. Chow versus HFD: #, p < 0.05; ##, p < 0.01; ###, p < 0.001.

The above findings were confirmed by DEXA scan (Fig. 2D). On chow diet, fat mass in MCK/L0 was only 8 ± 0.6% of the body mass; in WT it was 11 ± 1% and in ATLO 11 ± 0.5%. After the HFD, the percentage of total body fat increased to 40 ± 2% in WT and to 37 ± 1% in ATLO mice, although in MCK/L0 mice it was only 19.3 ± 2%. An increase in the lean mass of MCK/L0 mice accounted for the lack of difference in body weight (Fig. 2D).

Liver Lipid Content

We wondered if the hypertriglyceridemia in ATLO mice would cause hepatic steatosis. The liver TG content in ATLO mice was 24 ± 9 mg of TG/g of tissue, not different from that of WT, which was 25 ± 13 mg of TG/g of tissue. In contrast, MCK/L0 mice had increased liver TGs, 47 ± 12 mg of TG/g of tissue (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2E). There were no differences in the TC or FFA content between the three genotypes. After HFD feeding, both WT and ATLO mice had increased liver TG content. However, MCK/L0 mice had 49 ± 9 mg of TG/g of tissue, which was significantly less liver TG (p < 0.05) than that of WT or ATLO mice, 80 ± 6 and 78 ± 7 mg of TG/g of tissue, respectively (Fig. 2E).

TG Production and Clearance

Two reasons for the hypertriglyceridemia in ATLO mice were considered, increased hepatic TG secretion and defective TG clearance. To assess whether hepatic VLDL-TG production could account for the hypertriglyceridemia, mice were intravenously injected with tyloxapol to inhibit the clearance of TG-rich particles. We did not observe differences in the blood TG accumulation between ATLO and WT mice, indicating that VLDL-TG production was not affected (Fig. 3A). To test if there was defective catabolism of TG rich lipoproteins, tissue chylomicron uptake was assessed using endogenously produced double-labeled chylomicrons (27). The labeling of both the TG and the retinyl ester in the same particle allows the differentiation of two different processes, fatty acid uptake after TG lipolysis and whole particle uptake. BAT from ATLO had reduced TG uptake (Fig. 3B), although retinyl ester uptake was unaffected (Fig. 3C). Uptake into white adipose was low, and no significant differences were detectable. Uptake into heart, liver, and skeletal muscle was not affected by the loss of adipocyte LpL.

FIGURE 3.

Assessment of liver TG secretion and tissue uptake. A, mice were intraperitoneally injected with tyloxapol. Blood was collected at different time points, and accumulated TG was determined. B and C, mice were injected with endogenously labeled [14C]TG and [3H]retinol, and after 15 min tissues were harvested. Radioactivity was measured in the homogenized tissues. Statistical significance: *, p < 0.05.

ATLO mice also had reduced TG uptake into lungs (Fig. 3B). This was associated with reduced LpL activity; LpL activity in ATLO and MCK/L0 lungs were both reduced by ∼50% (Fig. 1, B, D, and E), suggesting that lungs might also be partially responsible for the ATLO hypertriglyceridemia. We should note that a knock-out of LpL in macrophages did not affect plasma TG levels (18). It is thought that much lung LpL activity is acquired from circulating LpL that attaches to lung glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchore HDL-binding protein 1 (32). It is likely that these changes in BAT chylomicron-TG and lung lipolysis are responsible for the hypertriglyceridemia in ATLO mice.

Lipidomic Analysis of Adipose Fatty Acids

To determine the likely origin of the fatty acids within the adipose tissues, the lipid composition of GAT and SCAT was analyzed in the ATLO, MCK/L0, and WT mice. The proportions of each class of fatty acids are shown in Fig. 4, and individual fatty acids in supplemental Table 1. In chow-fed mice, the GAT TG acyl composition of major fatty acids in ATLO mice was identical to that of WT (Fig. 4A). In contrast, MCK/L0 mice had a marked reduction in PUFA and an increase in the monounsaturated (MUFA) proportions. PUFA reduction was mainly due to a marked decrease in C18:2; however, almost all the PUFAs were significantly reduced in the MCK/L0 GAT. In SCAT, the TG acyl composition of both ATLO and MCK/L0 mice showed a reduction in PUFAs due to a decrease in C18:2 (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Lipidomic analysis of GAT, SCAT, and BAT. Adipose tissue lipids were extracted as described under “Experimental Procedures,” and fatty acids were identified and quantified by LC/MS. Percentage of saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acids were calculated for WT, ATLO, and MCK/L0 adipose tissues. A, TG acyl composition on chow diet. B, acyl-CoA composition on chow diet. C, uptake of 2-deoxy-d-[1-3H]glucose in adipose tissues. Statistical significance: ATLO or MCK/L0 versus WT: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

In contrast to the minor effect of adipose LpL deletion in GAT, ATLO BAT had markedly reduced amounts of PUFAs, and such changes were amplified in the MCK/L0 BAT (Fig. 4A). PUFA-TGs were reduced from 39.5 ± 6.7% in WT to 15.7 ± 3.9% in ATLO and to 7.9 ± 1.9% in MCK/L0 BAT (p < 0.01 for both). A number of saturated fatty acids (SFAs) and MUFAs were greater in both ATLO and MCK/L0; these fatty acids are often the products of de novo synthesis. SFAs were 15.9 ± 2.6% in WT, whereas in MCK/L0 mice they were increased to 37.12 ± 2.4% (p < 0.001). The acyl-CoA composition of the adipose stores in the three genotypes showed similar patterns as the TGs (Fig. 4B). Thus, the lipid changes were consistent with a decrease in uptake of dietary fatty acids and an increase in de novo synthesis in LpL-deficient adipose, with the changes being more marked in BAT and in MCK/L0 mice. In contrast, adipose lipid composition in the macrophage-specific LpL knock-out ML0 was identical to that of WT (data not shown).

Tissue Uptake of Glucose

To further determine the likely origin of the adipose tissue in ATLO and MCK/L0 mice, we used 2-deoxy-d-[1-3H]glucose to trace the uptake. Glucose uptake was increased in GAT of MCK/L0 mice (Fig. 4C) (33). Other tissues, liver, heart, spleen, lung, and brain, displayed no significant differences in uptake.

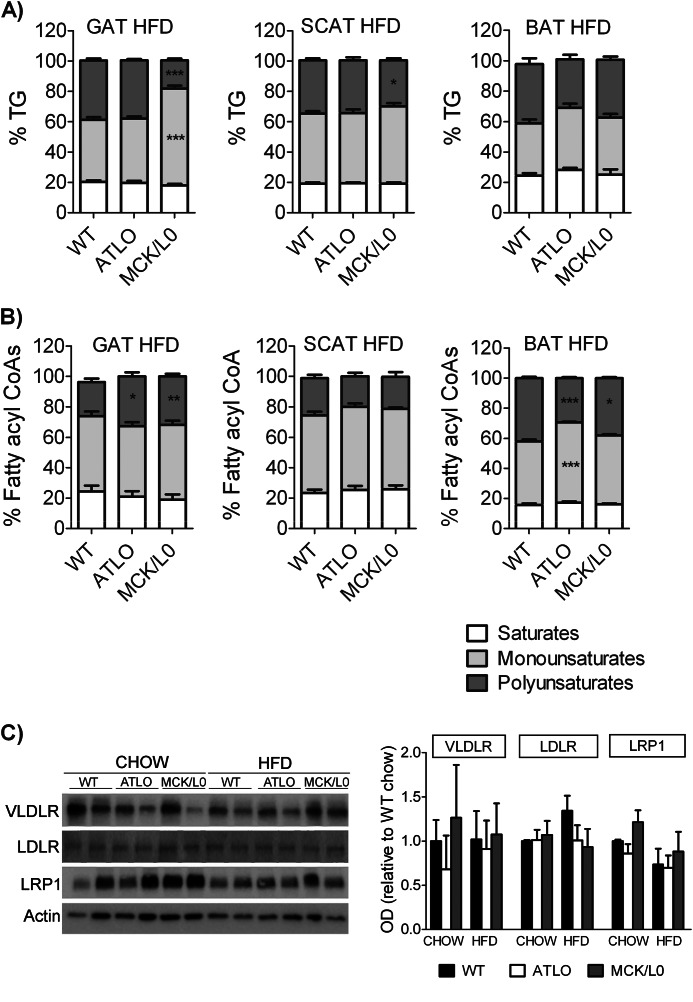

Effects of HFD Feeding on Acyl Composition

We next assessed whether feeding HFD was associated with amplification or reduction of the differences in fatty acid composition. The HFD was mainly enriched in C18:1, C16, and C18:2, and these fatty acids were found very abundantly in the tissues (Table 1 and supplemental Table 1). This diet increased the percent of MUFAs and/or SFAs in all three fat depots of WT and ATLO mice (Fig. 5A and supplemental Table 1). The reduction in PUFAs found in GAT from chow-fed MCK/L0 persisted on the HFD. But surprisingly, the PUFA acyl-CoAs were increased in MCK/L0 GAT, suggesting that the uptake of fatty acids increased although the storage in TG remained lower than in the WT mice.

FIGURE 5.

Lipidomic analysis of GAT, SCAT, and BAT. Adipose tissue lipids were extracted as described under “Experimental Procedures,” and fatty acids were identified and quantified by LC/MS. Percentage of saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acids were calculated for WT, ATLO, and MCK/L0 adipose tissues. A, TG acyl composition on HFD. B, acyl-CoA composition on HFD. C, Western blot and densitometric analysis for VLDL receptor (VLDLR), LDL receptor (LDLR), and LRP1 in GAT on chow and high fat-fed WT, ATLO, and MCK/L0 mice.

In contrast, HFD negated many of the effects of LpL deficiency on SCAT and BAT lipid composition. Compared with chow, the TG PUFAs in BAT of HFD-fed ATLO approximately doubled. ATLO and MCK/L0 BAT experienced major changes in lipid composition to the point that there were no longer differences with the WT mice; the differences found in the SCAT were also minimized. The acyl-CoA composition changed with the HFD following the same directions as the TGs (Fig. 5B). There were no changes in the expression of lipoprotein receptors as follows: LDL receptor, VLDL receptor, and LRP1 (Fig. 5C). Therefore, de novo synthesis is a major contributor to both GAT and BAT when LpL-deficient mice are fed chow diet. In contrast, diet is the major fatty acid source in HFD-fed animals. Plasma FFA composition on both chow and HFD reflected the composition of TG in adipose (data not shown).

Gene Expression in WAT and BAT

To study if the lipidomic changes were consistent with gene expression changes in GAT, BAT, and SCAT, we measured mRNA levels of the main metabolic genes involved in fatty acid metabolism, as well as the main nuclear receptors governing the lipid metabolism (Table 4). In chow diet-fed mice, ATLO differed from WT mice in the mRNA levels of Fasn, the main lipogenic enzyme, only in SCAT and BAT, where it was increased by ∼3–4-fold (p < 0.01), but this mRNA was not increased in GAT. Scd1 and Scd2 mRNA levels were also increased in SCAT and BAT but not GAT. In MCK/L0 mice, Fasn was increased by 13–74-fold (p < 0.05), and mRNA levels of other enzymes involved in the lipogenic pathway, Dgat1, Scd1, and Scd2, were increased in all three fat depots of MCK/L0 mice. Enzymes involved in TG degradation and fatty acid oxidation, hormone-sensitive lipase (Hsl), adipose triglyceride lipase (Atgl), and acyl-CoA oxidase (Aox), were also increased in MCK/L0 adipose tissues. Consistent with the increase in both the lipogenic and the oxidative pathways, MCK/L0 mice also showed greater increases in the expression of all the PPARs. After the mice had been fed a HFD, differences among genotypes were less remarkable, and there was no longer evidence of de novo lipogenesis-related gene expression in any of the tissues (Table 5). The HFD-induced changes in adipose tissue were associated with increased Lpl mRNA in GAT of WT mice (∼3-fold). However, ATLO and MCK/L0 still had much lower Lpl expression, 5 and 0.2% of WT, respectively (Table 5). BAT also had greater Lpl mRNA when the mice were fed HFD (∼72-fold in WT). In ATLO mice, the HFD-induced increase in BAT LpL expression meant that the levels were higher than in chow-fed WT mice, despite still being lower than HFD-fed WT, i.e. only 1% of the Lpl expression (Table 5). In contrast, ML0 mice had normal fat development and no defect in LpL induction with the western diet (18).

TABLE 4.

Gene expression in adipose tissues in chow diet

The mean ± S.E is shown. Comparisons of MCK/L0 or ATLO versus WT within the same adipose depot and diet: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

| Chow | GAT |

SCAT |

BAT |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | ATLO | MCK/L0 | WT | ATLO | MCK/L0 | WT | ATLO | MCK/L0 | |

| LpL | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.03*** | 0.1 ± 0.02*** | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.1* | 0.04 ± 0.02* | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.1* | 0.03 ± 0.01** |

| Lipogenesis | |||||||||

| FAS | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 74 ± 22* | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 4.2 ± 1.2* | 13 ± 6.0 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 3.1 ± 0.7* | 73 ± 14*** |

| DGAT1 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 10 ± 4.1* | 1.0 ± 0.34 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 5.7 ± 3.0 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 4.1 ± 1.1* | 54 ± 3.3*** |

| SCD1 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 36 ± 8.8** | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 16 ± 3.7** | 12 ± 2.9* | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.6* | 4.9 ± 1.0** |

| SCD2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 41 ± 12* | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 9.7 ± 2.8* | 36 ± 29 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 3.1 ± 0.1** | 79 ± 26* |

| TG degradation and FA oxidation | |||||||||

| HSL | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 5.0 ± 1.1** | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 4.0 ± 0.8** | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 2.4 ± 0.6 | 17 ± 2.1*** |

| ATGL | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 7.4 ± 2.0** | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 1.9 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 3.6 ± 0.6** |

| AOX | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.5* | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.6** | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 1.1** |

| Nuclear receptors | |||||||||

| PPARα | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 9.6 ± 3.5* | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 12 ± 5.3* | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 7.8 ± 1.9** | 4.5 ± 1.9 |

| PPARδ | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 7.0 ± 2.3* | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 9.6 ± 2.2*** | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.4** |

| PPARγ1 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 8.7 ± 2.9* | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 4.6 ± 1.9* | 14 ± 6.0* | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 3.7 ± 0.6** |

| PPARγ2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 7.8 ± 2.3* | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 17 ± 9.2* | 34 ± 15* | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 8.1 ± 3.6 | 11 ± 2.3*** |

TABLE 5.

Gene expression in adipose tissues in HFD

The mean ± S.E. is shown. Comparisons of MCK/L0 or ATLO versus WT within the same adipose depot and diet: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

| HFD | GAT |

SCAT |

BAT |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | ATLO | MCK/L0 | WT | ATLO | MCK/L0 | WT | ATLO | MCK/L0 | |

| LpL(referred to WT chow) | 3.6 ± 1.1* | 0.17 ± 0.1 | 0.01 ± 0.01* | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.001 ± 0.001* | 72 ± 7.2*** | 7.0 ± 1.8* | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| LpL | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.05 ± 0.02* | 0.002 ± 0.01** | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.01 ± 0.001* | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.01 ± 0.02*** | 0.01 ± 0.001*** |

| Lipogenesis | |||||||||

| FAS | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.1* | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 3.7 ± 1.5 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 1.1 | 0.16 ± 0.02** |

| DGAT1 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.5 |

| SCD1 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 1.1 | 0.2 ± 0.02** |

| SCD2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 1.6 |

| TG degradation and FA oxidation | |||||||||

| HSL | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.1* | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.04* | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.3 |

| ATGL | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1* | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.5 |

| AOX | 1.0 ± 0.01 | 0.2 ± 0.1*** | 0.3 ± 0.1*** | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 0.6 ± 0.4 |

| Nuclear receptors | |||||||||

| PPARα | 1.0 ± 0.01 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 6.5 ± 2.8 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 0.4 ± 0.1* |

| PPARδ | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 6.4 ± 3.0 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.03** |

| PPARγ1 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 4.5 ± 2.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.1* | 0.9 ± 0.3 |

| PPARγ2 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

Bone Marrow Transplant to Replenish Macrophage LpL Expression in GAT

Because ATLO mice showed little phenotype in their GAT, as opposed to the MCK/L0, we studied the possible contribution of macrophage-derived LpL to the normal development of GAT. The TG acyl composition of ML0 mice showed no differences in any of the three adipose stores. However, we hypothesized that in conditions of limited availability of adipocyte-derived LpL, macrophage-derived LpL could be relevant to adipose tissue development. Bone marrow transplants were performed from WT donors to MCK/L0 recipients (WT → MCK/L0) to replenish MCK/L0 mice with LpL-expressing macrophages. MCK/L0 recipients of MCK/L0 were used as controls (MCK/L0 → MCK/L0). After 8 weeks, the mice were injected in their GAT with an MCP1-expressing adenovirus to promote the recruitment of the donor's macrophages to the recipient's adipose tissue.

The expression of Lpl mRNA in GAT from WT → MCK/L0 mice was 40% of LpL mRNA of WT mice (Fig. 6A), which is higher than the residual 25% Lpl mRNA previously encountered in GAT from ATLO mice. However, Lpl activity in WT → MCK/L0 mice was only 6.6% of the activity in WT mice (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Macrophage LpL replenishment in MCK/L0 GAT by bone marrow transplant. Bone marrow from WT or from MCK/L0 mice was transplanted into MCK/L0 recipients. After an 8-week repopulation period, mice were injected directly in their GAT with an MCP-1-expressing adenovirus. A, Lpl mRNA was analyzed in GAT. B, LpL activity. C, mRNA expression for Angptl4. D, GAT TG acyl composition. E, mRNA for Fasn. F, mRNA for Pparg1, Pparg2, and Ppard was measured. G, Lpl mRNA in BAT. H, BAT TG acyl composition in the transplanted mice. I, Lpl mRNA in SCAT. J, SCAT TG acyl composition. Statistical significance: in comparisons versus MCK/L0→MCK/L0 (D and H) or versus WT (rest of panels): *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

The disparity between the replacement of Lpl mRNA and LpL activity suggested that the MCK/L0 adipose was expressing an LpL activity inhibitor. We found that Angptl4 mRNA levels in MCK/L0 GAT were increased by 5.5-fold compared with WT. Similarly, transplant of bone marrow into MCK/L0 was persistently associated with this increase in the expression of the LpL inhibitor regardless of whether the donor bone marrow was WT or LpL-deficient (Fig. 6C). Therefore, although the bone marrow-derived macrophages replenished Lpl mRNA in MCK/L0 GAT, there was no increase in activity, probably due to the higher expression of Angptl4. Not surprisingly, the PUFA proportion in the GAT TGs of WT → MCK/L0 mice did not increase when compared with the MCK/L0 → MCK/L0 (Fig. 6D), and the Fasn expression remained high (Fig. 6E). Angptl4 is regulated by PPARγ in the adipocyte and by PPARδ in the macrophage (34, 35). Consistently, both isoforms of PPARγ, PPARγ1 and PPARγ2, and PPARδ were up-regulated in the GAT from transplanted mice MCK/L0 → MCK/L0 and in WT → MCK/L0 (Fig. 6F).

In BAT and SCAT, the expression of Lpl mRNA remained as background in both MCK/L0 → MCK/L0 and WT → MCK/L0 mice, indicating lack of LpL replenishment, perhaps because macrophage recruitment was amplified only in the GAT, which was injected with Ad-MCP1. Neither did the proportion of PUFAs change in BAT or SCAT with the transplanted WT bone marrow (Fig. 6, G–J).

MCK/ATLO Mice Have Reduced Adipose Mass and Increased Lipogenic Gene Expression

Because loss of macrophage LpL and loss of adipocyte (plus some macrophage) LpL did not lead to smaller GAT in ATLO mice, it suggested that the reduced white adipose in MCK/L0 mice was due to the muscle overexpression of LpL. To test this hypothesis, we crossed the MCK-Lpl transgene onto the ATLO background. MCK-ATLO mice had reduced plasma TG levels to ∼50 mg/dl. GAT in MCK/ATLO mice was reduced to 0.2 g of tissue, a reduction of >30% (Fig. 7A). The residual GAT was larger than that of MCK/L0 mice (Fig. 2B) but smaller than WT. MCK/ATLO GAT had increased expression of the lipogenic genes; mRNA levels of Fasn were increased 3-fold and SCD1 5-fold compared with WT (Fig. 7B). Moreover, the GAT now had reduced polyunsaturated TG fatty acids and increased monounsaturated fatty acids (Fig. 7C). Therefore, the lack of LpL in adipose tissue in MCK/ATLO mice is likely to be compensated by endogenous lipogenesis to a partial extent that does not allow a complete adipose development. Moreover, this study proved that LpL effects on adipose development are due to a balance of uptake between different tissues.

FIGURE 7.

MCK/ATLO mice phenotype. A, GAT mass of MCK/ATLO mice compared with WT and with ATLO mice. B, mRNA expression for Fasn and Scd1 in GAT of WT, ATLO, and MCK/ATLO mice. C, GAT TG acyl composition. Statistical significance: ATLO or MCK/ATLO versus WT: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

The accumulation of TG within adipose tissue has been assumed to occur primarily via LpL hydrolysis of lipoprotein TG. For that reason, we assumed that ATLO mice would either have reduced adipose tissue mass or would accumulate TG via other processes, as had been shown for MCK/L0 (9, 10). Moreover, we assumed that expansion of adipose stores with HFDs required LpL actions. Many of these hypotheses were wrong. 1) We found that WT and ATLO mice developed equal TG stores, but MCK/L0 had reduced WAT. 2) ATLO mice had hypertriglyceridemia, and this was associated with reduced chylomicron TG uptake in BAT and lung. 3) Introduction of the MCK-LpL transgene onto the ATLO background led to reduced GAT. 4) ATLO BAT had decreased PUFAs, consistent with reduced uptake of dietary fat. 5) GAT, SCAT, and BAT from MCK/L0 mice also had reduced PUFAs, and this was associated with increased Fasn mRNA. 6) MCK/L0 mice fed a HFD had less weight gain, but TG fatty acyl distribution approximated that of WT mice. Therefore, adipose LpL is a more critical regulator of BAT metabolism. But even in LpL absence, adipose tissue can acquire dietary lipids, perhaps because of lipolysis in distant tissues.

The Ap2-cre led to a marked deletion of LpL expression in mature adipocytes. Adipocyte Ap2 is turned on in the terminal differentiation phase of the adipogenesis under the control of PPARγ (36, 37). This led to a commensurate reduction in LpL activity. Not unexpectedly, macrophage Lpl was also somewhat reduced in the ATLO mice. The residual LpL in the ATLO adipose could reflect some continued LpL expression by macrophages or an incomplete deletion in some adipocytes (although the mRNA decrease in GAT adipocytes was ∼80%, Fig. 1). As a consequence, macrophages in ATLO GAT contained a higher proportion of the total residual LpL than the macrophages in WT mice (Fig. 1). The in vivo phenotype of the ATLO mouse was primarily localized to the plasma and BAT. ATLO, unlike MCK/L0, had hypertriglyceridemia. This can be explained by the reduced LpL activity in the BAT leading to reduced TG-derived fatty acid uptake. The reduced lung TG uptake may also have contributed to the hypertriglyceridemia. Changes in lung LpL activity, it should be noted, might not be due to altered lung LpL expression (32) but rather to changes in acquisition of LpL from the circulation. In our kinetic studies, TG uptake per mg of tissue into BAT of WT mice was ∼40 times greater than uptake into WAT. Despite being a small proportion of the total amount of adipose tissue, BAT is metabolically highly active (38) and has been shown to be an important modulator of plasma TG clearance in the mouse (16). Although it is also possible that the partial LpL knock-out in macrophages reduces TG clearance, other studies with more complete macrophage LpL deletion did not alter circulating TG levels (18).

Our data confirm that BAT TG uptake is via actions of LpL. However, the lack of LpL did not lead to reduced BAT size in MCK/L0 or in ATLO mice. Consistent with the uptake data, BAT was deficient in dietary fatty acids. Although we had expected loss of adipocyte LpL to also alter WAT, only SCAT showed a slightly altered lipid composition. This differs from studies in humans with complete LpL deficiency; WAT from these people have decreased levels of PUFAs in adipose tissue (39). In contrast with the ATLO mouse, deletion of LpL in skeletal myocytes (40) and cardiomyocytes (17) leads to tissue-specific effects that are not overcome by LpL production by other cells. Although some of the ATLO phenotypes might reflect a more complete reduction in LpL activity in BAT, we suspect that other regulators of the lipolytic reaction, especially the concentration of plasma TG, and the relative metabolic activity of the different fat stores are likely to determine whether the residual LpL is physiologically limiting (see below).

The importance of some LpL for adipose development seemed to be confirmed by studies in the MCK/L0 mice. MCK/L0 mice had less GAT mass, both on chow and HFD, and increased lean body mass. These results seemed to differ from the observed phenotype of humans with LpL deficiency. Although the composition of human LpL-deficient adipose is compatible with greater de novo TG production, these patients have no obvious defect in adipose development (41). It is possible that the compositional changes could be due to the low fat diets ingested by LpL-deficient patients. Because of this, we created MCK/ATLO mice and were able to show that the enhanced muscle LpL expression reduced GAT; in contrast, the MCK-Lpl transgene did not reduce GAT when bred onto the WT background. Therefore, both a reduction in adipose LpL and greater expression of LpL in the muscle are required to divert fat away from adipose. These data confirm the Greenwood hypothesis that LpL is the “gatekeeper” for distribution of fatty acid-derived calories among tissues (8).

MCK/L0 adipose tissue GAT has a greater uptake of glucose (33), the presumed substrate used for de novo lipogenesis, consistent with the gene and lipid profile suggestive of enhanced lipogenesis as follows: increased expression of Fasn and GAT enriched in the FAS products C16 and C18, as well as in their monounsaturated fatty acids after the action of the also overexpressed desaturases SCD1 and SCD2. In contrast, ATLO mice did not have increased glucose uptake in GAT, reflecting their acquisition of lipids from the plasma circulating TGs.

Circulating plasma TG in chylomicrons and VLDL is the substrate for LpL activity. HFD rescued the dietary fatty acid deficiency in all the adipose stores and normalized FAS expression in the MCK/L0 mice; we presume this is due to the large amount of dietary TG that became available for adipose uptake. There was no increase in conventional lipoprotein receptors, and we presume that uptake of dietary fat was due to FFA created in LpL-expressing tissues other than adipose, i.e. skeletal muscle. LpL is a major contributor to retinyl ester uptake (42), but there is evidence of alternative LpL-independent pathways for lipoprotein vitamin A uptake by tissues (42, 43). Such other routes may be important for adipose fatty acid uptake especially during the HFD and are likely to involve uptake of circulating FFA. We initially thought that such uptake was insufficient to allow normal fat expansion in the MCK/L0 model. However, the reduction of GAT in the MCK/ATLO mice underscored the importance of lipid diversion in addition to reduced local uptake in adipose development. In should be noted that ATLO/MCK mice differ from the ATLO in that they have reduced plasma TG to serve as substrate for the residual adipose LpL. Opposite to what occurs in HFD-fed MCK/L0, the reduced LpL substrate might be reflected by reduced GAT mass.

We initially hypothesized that the difference between the WAT stores in these two models was due to the contribution of adipose tissue macrophage LpL in the setting of limited adipocyte-derived LpL. To prove this, we restored LpL in MCK/L0 mice by bone marrow transplant experiments. LpL expression in the MCK/L0 recipients of WT bone marrow was increased to 40% of the WT mice, higher than the levels of expression found in ATLO mice. However, the increase in Lpl mRNA did not translate into a significant decrease in FAS expression or changes in the lipid composition of the adipose tissue. This result reflected the less robust restoration of LpL activity, perhaps due to the high expression of Angptl4. Angplt4 is a PPAR-regulated gene that is induced by PPARγ in adipocytes and PPARδ in macrophages (34, 35). Although LpL is a source of ligands for PPAR activation (44, 45), it is possible that adipose, like the liver, activates PPAR transcription factors using de novo synthesized fatty acids (46).

In summary, upon deletion of LpL in adipocytes, we made several observations that provide novel insights into adipose tissue biology. We show that BAT LpL activity is an important regulator of plasma TG, at least in the mouse. LpL loss from WAT adipocytes alone does not affect lipid composition or fat development. This contrasts with the situation in MCK/L0 where lipid composition and fat development are altered. However, even in these mice, alternative uptake pathways are sufficient to correct the reduced PUFA levels in SCAT and BAT when animals are fed a HFD. Replacement of LpL using macrophage expression did not correct adipose metabolism, possibly due to increases in the LpL inhibitor, ANGPLT4. These data show the importance of this inhibitory reaction and suggest that modulation of ANGPLT4 may have important effects on TG metabolism in patients with partial LpL deficiency. Finally, by addition of the MCK-LpL transgene to the ATLO background, we prove that a major control of adipose development is the diversion of nutrients to other tissues. This physiology is likely to replicate that due to LpL induction that occurs in chronically exercising mammals.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. A. Ferrante for advice.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant HL45095 from NHLBI (to I. J. G.).

This article contains supplemental Table 1.

- TG

- triglyceride

- LpL

- lipoprotein lipase

- GAT

- gonadal adipose tissue

- SCAT

- subcutaneous adipose tissue

- BAT

- brown adipose tissue

- FFA

- free fatty acid

- MUFA

- monounsaturated fatty acid

- PUFA

- polyunsaturated fatty acid

- FFA

- free fatty acid

- HFD

- high fat diet

- TC

- total cholesterol

- SVC

- stromal vascular cell

- DEXA

- dual energy x-ray absorptiometry

- WAT

- white adipose tissue

- ATLO

- adipose-specific LpL knock-out

- FAS

- fatty-acid synthase

- PPAR

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- ROH

- retinol

- SFA

- saturated fatty acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jacobsen B. K., Trygg K., Hjermann I., Thomassen M. S., Real C., Norum K. R. (1983) Acyl pattern of adipose tissue triglycerides, plasma free fatty acids, and diet of a group of men participating in a primary coronary prevention program (the Oslo Study). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 38, 906–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van Staveren W. A., Deurenberg P., Katan M. B., Burema J., de Groot L. C., Hoffmans M. D. (1986) Validity of the fatty acid composition of subcutaneous fat tissue microbiopsies as an estimate of the long-term average fatty acid composition of the diet of separate individuals. Am. J. Epidemiol. 123, 455–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Strawford A., Antelo F., Christiansen M., Hellerstein M. K. (2004) Adipose tissue triglyceride turnover, de novo lipogenesis, and cell proliferation in humans measured with 2H2O. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 286, E577–E588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goldberg I. J. (1996) Lipoprotein lipase and lipolysis: central roles in lipoprotein metabolism and atherogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 37, 693–707 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berger G. M. (1986) Clearance defects in primary chylomicronemia: a study of tissue lipoprotein lipase activities. Metabolism 35, 1054–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weinstock P. H., Bisgaier C. L., Aalto-Setälä K., Radner H., Ramakrishnan R., Levak-Frank S., Essenburg A. D., Zechner R., Breslow J. L. (1995) Severe hypertriglyceridemia, reduced high density lipoprotein, and neonatal death in lipoprotein lipase knockout mice. Mild hypertriglyceridemia with impaired very low density lipoprotein clearance in heterozygotes. J. Clin. Invest. 96, 2555–2568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Merkel M., Weinstock P. H., Chajek-Shaul T., Radner H., Yin B., Breslow J. L., Goldberg I. J. (1998) Lipoprotein lipase expression exclusively in liver. A mouse model for metabolism in the neonatal period and during cachexia. J. Clin. Invest. 102, 893–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Greenwood M. R. (1985) The relationship of enzyme activity to feeding behavior in rats: lipoprotein lipase as the metabolic gatekeeper. Int. J. Obes. 9, 67–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Levak-Frank S., Weinstock P. H., Hayek T., Verdery R., Hofmann W., Ramakrishnan R., Sattler W., Breslow J. L., Zechner R. (1997) Induced mutant mice expressing lipoprotein lipase exclusively in muscle have subnormal triglycerides yet reduced high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in plasma. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 17182–17190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kratky D., Zimmermann R., Wagner E. M., Strauss J. G., Jin W., Kostner G. M., Haemmerle G., Rader D. J., Zechner R. (2005) Endothelial lipase provides an alternative pathway for FFA uptake in lipoprotein lipase-deficient mouse adipose tissue. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 161–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jensen M. D. (2007) Adipose tissue metabolism–an aspect we should not neglect? Horm. Metab. Res. 39, 722–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. MacLaren R., Cui W., Simard S., Cianflone K. (2008) Influence of obesity and insulin sensitivity on insulin signaling genes in human omental and subcutaneous adipose tissue. J. Lipid Res. 49, 308–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Virtanen K. A., Lidell M. E., Orava J., Heglind M., Westergren R., Niemi T., Taittonen M., Laine J., Savisto N. J., Enerbäck S., Nuutila P. (2009) Functional brown adipose tissue in healthy adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1518–1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Marken Lichtenbelt W. D., Vanhommerig J. W., Smulders N. M., Drossaerts J. M., Kemerink G. J., Bouvy N. D., Schrauwen P., Teule G. J. (2009) Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in healthy men. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1500–1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cypess A. M., Lehman S., Williams G., Tal I., Rodman D., Goldfine A. B., Kuo F. C., Palmer E. L., Tseng Y. H., Doria A., Kolodny G. M., Kahn C. R. (2009) Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1509–1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bartelt A., Bruns O. T., Reimer R., Hohenberg H., Ittrich H., Peldschus K., Kaul M. G., Tromsdorf U. I., Weller H., Waurisch C., Eychmüller A., Gordts P. L., Rinninger F., Bruegelmann K., Freund B., Nielsen P., Merkel M., Heeren J. (2011) Brown adipose tissue activity controls triglyceride clearance. Nat. Med. 17, 200–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Augustus A., Yagyu H., Haemmerle G., Bensadoun A., Vikramadithyan R. K., Park S. Y., Kim J. K., Zechner R., Goldberg I. J. (2004) Cardiac-specific knock-out of lipoprotein lipase alters plasma lipoprotein triglyceride metabolism and cardiac gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 25050–25057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Takahashi M., Yagyu H., Tazoe F., Nagashima S., Ohshiro T., Okada K., Osuga J. I., Goldberg I. J., Ishibashi S. (2013) Macrophage lipoprotein lipase modulates the development of atherosclerosis but not adiposity. J. Lipid Res. 54, 1124–1134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Levak-Frank S., Radner H., Walsh A., Stollberger R., Knipping G., Hoefler G., Sattler W., Weinstock P. H., Breslow J. L., Zechner R. (1995) Muscle-specific overexpression of lipoprotein lipase causes a severe myopathy characterized by proliferation of mitochondria and peroxisomes in transgenic mice. J. Clin. Invest. 96, 976–986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weisberg S. P., McCann D., Desai M., Rosenbaum M., Leibel R. L., Ferrante A. W., Jr. (2003) Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 1796–1808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chang C. L., Seo T., Du C. B., Accili D., Deckelbaum R. J. (2010) n-3 fatty acids decrease arterial low-density lipoprotein cholesterol delivery and lipoprotein lipase levels in insulin-resistant mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 2510–2517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Swayne T. C., Boldogh I. R., Pon L. A. (2009) Imaging of the cytoskeleton and mitochondria in fixed budding yeast cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 586, 171–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hocquette J. F., Graulet B., Olivecrona T. (1998) Lipoprotein lipase activity and mRNA levels in bovine tissues. Comp. Biochem. Physiol B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 121, 201–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nilsson-Ehle P., Schotz M. C. (1976) A stable, radioactive substrate emulsion for assay of lipoprotein lipase. J. Lipid Res. 17, 536–541 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haugen B. R., Jensen D. R., Sharma V., Pulawa L. K., Hays W. R., Krezel W., Chambon P., Eckel R. H. (2004) Retinoid X receptor γ-deficient mice have increased skeletal muscle lipoprotein lipase activity and less weight gain when fed a high-fat diet. Endocrinology 145, 3679–3685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Palmer W. K., Emeson E. E., Johnston T. P. (1998) Poloxamer 407-induced atherogenesis in the C57BL/6 mouse. Atherosclerosis 136, 115–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bharadwaj K. G., Hiyama Y., Hu Y., Huggins L. A., Ramakrishnan R., Abumrad N. A., Shulman G. I., Blaner W. S., Goldberg I. J. (2010) Chylomicron- and VLDL-derived lipids enter the heart through different pathways: in vivo evidence for receptor- and non-receptor-mediated fatty acid uptake. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 37976–37986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu L., Yu S., Khan R. S., Ables G. P., Bharadwaj K. G., Hu Y., Huggins L. A., Eriksson J. W., Buckett L. K., Turnbull A. V., Ginsberg H. N., Blaner W. S., Huang L. S., Goldberg I. J. (2011) DGAT1 deficiency decreases PPAR expression and does not lead to lipotoxicity in cardiac and skeletal muscle. J. Lipid Res. 52, 732–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Clugston R. D., Jiang H., Lee M. X., Piantedosi R., Yuen J. J., Ramakrishnan R., Lewis M. J., Gottesman M. E., Huang L. S., Goldberg I. J., Berk P. D., Blaner W. S. (2011) Altered hepatic lipid metabolism in C57BL/6 mice fed alcohol: a targeted lipidomic and gene expression study. J. Lipid Res. 52, 2021–2031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Han S., Liang C. P., DeVries-Seimon T., Ranalletta M., Welch C. L., Collins-Fletcher K., Accili D., Tabas I., Tall A. R. (2006) Macrophage insulin receptor deficiency increases ER stress-induced apoptosis and necrotic core formation in advanced atherosclerotic lesions. Cell Metab. 3, 257–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Drosatos K., Sanoudou D., Kypreos K. E., Kardassis D., Zannis V. I. (2007) A dominant negative form of the transcription factor c-Jun affects genes that have opposing effects on lipid homeostasis in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 19556–19564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Olafsen T., Young S. G., Davies B. S., Beigneux A. P., Kenanova V. E., Voss C., Young G., Wong K. P., Barnes R. H., 2nd, Tu Y., Weinstein M. M., Nobumori C., Huang S. C., Goldberg I. J., Bensadoun A., Wu A. M., Fong L. G. (2010) Unexpected expression pattern for glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored HDL-binding protein 1 (GPIHBP1) in mouse tissues revealed by positron emission tomography scanning. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 39239–39248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wagner E. M., Kratky D., Haemmerle G., Hrzenjak A., Kostner G. M., Steyrer E., Zechner R. (2004) Defective uptake of triglyceride-associated fatty acids in adipose tissue causes the SREBP-1c-mediated induction of lipogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 45, 356–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yoon J. C., Chickering T. W., Rosen E. D., Dussault B., Qin Y., Soukas A., Friedman J. M., Holmes W. E., Spiegelman B. M. (2000) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ target gene encoding a novel angiopoietin-related protein associated with adipose differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 5343–5349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lichtenstein L., Mattijssen F., de Wit N. J., Georgiadi A., Hooiveld G. J., van der Meer R., He Y., Qi L., Köster A., Tamsma J. T., Tan N. S., Müller M., Kersten S. (2010) Angptl4 protects against severe proinflammatory effects of saturated fat by inhibiting fatty acid uptake into mesenteric lymph node macrophages. Cell Metab. 12, 580–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tang Q. Q., Zhang J. W., Daniel Lane M. (2004) Sequential gene promoter interactions by C/EBPβ, C/EBPα, and PPARγ during adipogenesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 318, 213–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rosen E. D., Sarraf P., Troy A. E., Bradwin G., Moore K., Milstone D. S., Spiegelman B. M., Mortensen R. M. (1999) PPARγ is required for the differentiation of adipose tissue in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Cell 4, 611–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ouellet V., Labbé S. M., Blondin D. P., Phoenix S., Guérin B., Haman F., Turcotte E. E., Richard D., Carpentier A. C. (2012) Brown adipose tissue oxidative metabolism contributes to energy expenditure during acute cold exposure in humans. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 545–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ullrich N. F., Purnell J. Q., Brunzell J. D. (2001) Adipose tissue fatty acid composition in humans with lipoprotein lipase deficiency. J. Investig. Med. 49, 273–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang H., Knaub L. A., Jensen D. R., Young Jung D., Hong E. G., Ko H. J., Coates A. M., Goldberg I. J., de la Houssaye B. A., Janssen R. C., McCurdy C. E., Rahman S. M., Soo Choi C., Shulman G. I., Kim J. K., Friedman J. E., Eckel R. H. (2009) Skeletal muscle-specific deletion of lipoprotein lipase enhances insulin signaling in skeletal muscle but causes insulin resistance in liver and other tissues. Diabetes 58, 116–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brun L. D., Gagné C., Julien P., Tremblay A., Moorjani S., Bouchard C., Lupien P. J. (1989) Familial lipoprotein lipase-activity deficiency: study of total body fatness and subcutaneous fat tissue distribution. Metabolism 38, 1005–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. O'Byrne S. M., Kako Y., Deckelbaum R. J., Hansen I. H., Palczewski K., Goldberg I. J., Blaner W. S. (2010) Multiple pathways ensure retinoid delivery to milk: studies in genetically modified mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 298, E862–E870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wassef L., Quadro L. (2011) Uptake of dietary retinoids at the maternal-fetal barrier: in vivo evidence for the role of lipoprotein lipase and alternative pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 32198–32207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Duncan J. G., Bharadwaj K. G., Fong J. L., Mitra R., Sambandam N., Courtois M. R., Lavine K. J., Goldberg I. J., Kelly D. P. (2010) Rescue of cardiomyopathy in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α transgenic mice by deletion of lipoprotein lipase identifies sources of cardiac lipids and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α activators. Circulation 121, 426–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Davies B. S., Waki H., Beigneux A. P., Farber E., Weinstein M. M., Wilpitz D. C., Tai L. J., Evans R. M., Fong L. G., Tontonoz P., Young S. G. (2008) The expression of GPIHBP1, an endothelial cell binding site for lipoprotein lipase and chylomicrons, is induced by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ. Mol. Endocrinol. 22, 2496–2504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chakravarthy M. V., Pan Z., Zhu Y., Tordjman K., Schneider J. G., Coleman T., Turk J., Semenkovich C. F. (2005) “New” hepatic fat activates PPARα to maintain glucose, lipid, and cholesterol homeostasis. Cell Metab. 1, 309–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]