Background: Many symbiotic nitrogen fixation genes are regulated by FixK-like proteins.

Results: The high-resolution structure of a rhizobial FixK-DNA complex was solved.

Conclusion: The structure explains how oxidation of a surface-exposed cysteine near the DNA-binding site interferes with transcription activation.

Significance: Post-translational modification of a transcription regulator by reactive oxygen species is a means to shut off gene expression.

Keywords: DNA Transcription, Protein-DNA Interaction, General Transcription Factors, Microbiology, X-ray Crystallography, CRP/FNR Superfamily, Gene Activation, Oxidative Control

Abstract

FixK2 is a regulatory protein that activates a large number of genes for the anoxic and microoxic, endosymbiotic, and nitrogen-fixing life styles of the α-proteobacterium Bradyrhizobium japonicum. FixK2 belongs to the cAMP receptor protein (CRP) superfamily. Although most CRP family members are coregulated by effector molecules, the activity of FixK2 is negatively controlled by oxidation of its single cysteine (Cys-183) located next to the DNA-binding domain and possibly also by proteolysis. Here, we report the three-dimensional x-ray structure of FixK2, a representative of the FixK subgroup of the CRP superfamily. Crystallization succeeded only when (i) an oxidation- and protease-insensitive protein variant (FixK2(C183S)-His6) was used in which Cys-183 was replaced with serine and the C terminus was fused with a hexahistidine tag and (ii) this protein was allowed to form a complex with a 30-mer double-stranded target DNA. The structure of the FixK2-DNA complex was solved at a resolution of 1.77 Å, at which the protein formed a homodimer. The precise protein-DNA contacts were identified, which led to an affirmation of the canonical target sequence, the so-called FixK2 box. The C terminus is surface-exposed, which might explain its sensitivity to specific cleavage and degradation. The oxidation-sensitive Cys-183 is also surface-exposed and in close proximity to DNA. Therefore, we propose a mechanism whereby the oxo acids generated after oxidation of the cysteine thiol cause an electrostatic repulsion, thus preventing specific DNA binding.

Introduction

The CRP/FNR5 superfamily of transcription factors comprises an important group of regulatory proteins that are widely distributed within bacteria. The name-giving proteins of this family are the cAMP receptor protein (CRP) (1) and the fumarate and nitrate reductase regulator (FNR) (2). Members of this superfamily disparately respond to a broad range of metabolic and environmental cues, thereby regulating a huge number of genes involved in vital functions such as carbon substrate utilization, virulence, nitrogen fixation, photosynthesis, and various modes of respiratory electron transport (3). Most of the CRP/FNR-type regulators function as transcription activators, few as repressors, and their regulatory activity is generally modulated by the binding of effector molecules (i.e. cofactors and prosthetic groups) (3).

Despite a remarkably low sequence identity (<25%) among the family members, the proteins are predicted to be structurally similar to CRP. They all share an N-terminally located effector-binding domain, an antiparallel β-barrel that makes contact with the RNA polymerase, a long α-helix that enables dimerization, and a C-terminally positioned DNA-binding domain with a helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif. Being active as homodimers, the proteins bind to a 2-fold symmetric consensus nucleotide sequence on target DNA at distinct distances upstream of the promoters of regulated genes (1–5).

Based on the primary structures of the DNA-binding and effector-binding domains, the CRP/FNR members have been classified into 21 subgroups (3). Up to now, the following eight proteins, representing seven subgroups, have been crystallized and structurally characterized: CRP (Protein Data Bank code 3HIF) (6), catabolite activation-like protein (code 3IWZ) (7), DNR (code 3DKW) (8), CooA (code 1FT9) (9), CprK (code 3E6C) (10), PrfA (code 2BEO) (11), NtcA (code 3LA2) (12), and SdrP (code 2ZCW) (13). However, no structures are known for proteins belonging to other important subgroups such as FNR, FixK, FnrN, and NnrR. A recent structural comparison of proteins in the on- and off-states (6, 10, 12, 14, 15) has allowed a better understanding of the allosteric mechanism triggered by the binding of cofactors and has suggested that the cofactor-induced activation mechanism is different within each subgroup.

The Bradyrhizobium japonicum FixK2 protein (16, 17) is a key regulator for the control of >200 genes required for microoxic, anoxic, and symbiotic growth. In root nodule symbiosis with soybean, the bacterium fixes molecular nitrogen. FixK2 belongs to the FixK subgroup of the CRP/FNR superfamily, but as opposed to other superfamily members, evidence for the involvement of a coregulator in modulating the transcription-activating activity is missing. The FixK2 amino acid sequence lacks a predicted binding site for a cofactor, and more importantly, purified protein from aerobically grown FixK2-overproducing Escherichia coli cells is active as a homodimer in an in vitro transcription (IVT) activation assay without a recognizable coactivator (18). However, FixK2 activity is influenced but in a different way. Due to a unique cysteine at position 183 near the HTH motif of the DNA-binding domain, FixK2 is oxidation-sensitive. Oxidation of this cysteine in vitro triggers the formation of a reversible intermolecular disulfide bridge between two monomers. In vivo, however, the more likely oxidation mechanism is the conversion of the cysteine thiol into a sulfenic, sulfinic, or sulfonic acid, which inactivates the protein (19). The relevance of FixK2 oxidation in vivo is based on indirect evidence. In particular, microarray analysis had shown that most of the direct FixK2-activatable target genes displayed decreased expression in hydrogen peroxide-stressed B. japonicum wild-type cells, but not in a strain having a FixK2 variant with Cys-183 replaced by alanine (19). FixK2 oxidation might be relevant for instantly shutting off its activity in response to reactive oxygen species (ROS) in vivo. ROS are produced (i) in the early stage of root hair infection, (ii) in the process of endosymbiotic respiration, and (iii) late during nodule senescence (20–22). In all of these conditions, FixK2 activity might not be either necessary or desirable. Apart from this oxidative post-translational control, FixK2 is also subject to proteolysis. We have recently shown that FixK2 is degraded by the housekeeping chaperone protease ClpAP1 and that the preferential protease-sensitive site is located at the C terminus (23).

It was therefore of interest to crystallize FixK2 and to determine its structure by x-ray crystallography. We hoped that this would help us understand how the oxidation of Cys-183 interferes with FixK2 activity and why the C terminus is prone to proteolysis. Moreover, as it turned out that crystals were formed only when FixK2 was complexed with DNA, the structure also uncovered the precise protein-DNA contact sites.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid Construction

The Stratagene QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis method was used to exchange the codon for Cys-183 against a serine codon using the complementary oligonucleotides 5′-GATGGCGCTGCCGATGTCCCGCCGCGATATCGGCG-3′ and 3′-CGCCGATATCGCGGCGGGACATCGGCAGCGCCATC-5′ (with the serine codons underlined) and pRJ9058 (18) as a template, which yielded plasmid pRJ8848. To construct the plasmid coding for N-terminally fused His6-tagged FixK2(C183S), the fixK2-containing DNA fragment was cut out with NdeI and NotI restriction enzymes and cloned in-frame with the His6 tag DNA into pET-28b(+) (Novagen), yielding plasmid pRJ8850. To obtain C-terminally fused His6-tagged FixK2(C183S), the fixK2 gene was first amplified by PCR from pRJ8848 with the appropriate primers (forward, 5′-GCGCATATGCTGACCCAGACAC-3′; and reverse, 5′-CGGCGGCCGCGGCGTCGAGATTGTGCAGGC-3′), which contained sequences for the NdeI and NotI restriction sites (underlined). The PCR-amplified DNA was then cloned in the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), cut out with the aforementioned enzymes, and cloned in-frame with the His6 tag DNA into pET-24c(+) (Novagen), yielding the consecutive plasmids pRJ0003 and pRJ0004. All fusion constructs were confirmed by sequencing.

Protein Expression and Purification

The His6-FixK2(C183S) and FixK2(C183S)-His6 proteins, carrying the N- and C-terminal His6 tags, respectively, were expressed and purified as described previously (18) unless specified otherwise (see below). Selenomethionine (SeMet)-labeled FixK2(C183S)-His6 was generated using the methionine auxotrophic E. coli B834(DE3) strain (Novagen). The recombinant strain was grown in SelenoMetTM medium (Molecular Dimensions Ltd., Newmarket, United Kingdom) at 30 °C for 3 h. SeMet-labeled FixK2(C183S)-His6 was purified in the same way as the unlabeled protein. SeMet had replaced all eight methionines as confirmed by mass spectrometric analysis.

IVT Activation Assays

Multiple-round IVT activation was carried out at 37 °C as described previously (18). Briefly, 0.1–1 μm FixK2(C183S)-His6 in modified IVT buffer (40 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7), 150 mm KCl, and 0.1 mm EDTA) plus the four nucleotide triphosphates was incubated in the presence of 50 nm B. japonicum RNA polymerase (holoenzyme) and 20 nm template plasmid pRJ8816 at 37 °C for 30 min. This plasmid harbors the fixN promoter region and a small part of the fixN gene upstream of a B. japonicum transcription terminator from the rrn operon. The electrophoretically separated transcripts were analyzed using a PhosphorImager SF system (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA), and signal intensities were determined with the Bio-Rad Quantity One software.

Crystallization

Unlabeled native and SeMet-labeled FixK2(C183S)-His6 were crystallized in the presence of 30-mer double-stranded target DNA from the FixK2-binding site of the fixN promoter (CCACCTATCTTGATTTCAATCAATTCCCCG, with the two binding half-sites underlined). This fixN oligonucleotide (1 μm scale; Microsynth AG, Balgach, Switzerland) was prepared by heating equimolar amounts of complementary single-stranded DNAs at 98 °C for 5 min and slowly cooling the mixture down to room temperature afterward. The proteins (9 mg/ml) that had been purified by immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography were mixed with a 1.5-fold molar excess of fixN double-stranded DNA and incubated for 5 min on ice. The protein-DNA complex formed was then subjected to size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 10/300 HR column (GE Healthcare) with modified IVT buffer as the running buffer and concentrated using a Microcon membrane (Millipore) with a molecular mass cutoff of 10 kDa.

Crystals of both the native and SeMet-labeled FixK2 derivatives complexed with DNA (185 mg of complex/ml) were grown at 277 K by sitting-drop vapor diffusion in 0.1 m BisTris (pH 6), 0.1 m NH4 acetate, and 16–22% PEG 10,000 for a period of 2–4 days. The complex crystallized as a protein dimer bound to DNA, and the crystals were thin and plate-like (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Crystals of the FixK2(C183S)-His6 protein in complex with DNA. The thin and plate-like crystals were grown by vapor diffusion in 0.1 m BisTris (pH 6), 0.1 m NH4 acetate, and 16–22% PEG 10,000 at 277 K within 2–4 days. Scale bar = 200 μm.

Data Collection and Structure Determination

Crystals were flash-frozen in liquid propane after sequential soaking in mother liquor containing 5–20% PEG 400. Diffraction data were collected at 90 K at the Swiss Light Source X06SA beamline (Paul Scherrer Institute, Villigen, Switzerland) using a PILATUS 6M detector (Dectris AG, Baden, Switzerland) at wavelengths of 1 Å (native protein) and 0.997 Å (SeMet derivative). The FixK2 structure was solved by single-wavelength anomalous dispersion using the SeMet-labeled protein.

Data for the native and SeMet proteins were processed using the XDS software package (24). The SeMet positions were located using the SHELX program suite (25), and the phased electron density map was used for automatic model building with AutoSol/AutoBuild using PHENIX (26). Manual model building was performed using Coot (27), and the structure was refined first with PHENIX and then with REFMAC5 from CCP4i (28), including TLS refinement. The structure of FixK2(C183S)-His6 includes amino acids 38–232 (both monomers) of the mature 232-amino acid protein, with one FixK2 dimer in the asymmetric unit. No density was observed for N-terminal residues 1–37 in either monomer. The four additional C-terminal residues are part of the linker region between the protein and the His6 affinity tag, which itself is not visible in the structure. 25 and 24 of the 30 bp of the bound fixN promoter double-stranded DNA were structurally assigned (strands W and X, respectively). The nucleotides at both ends that could not be assigned will be addressed below (i.e. two at the 5′-end and three at the 3′-end of strand W; two at the 3′-end and four at the 5′-end of strand X). MolProbity was used to assess the quality of the crystal structure. The data collection and refinement statistics are presented in Table 1. Structural figures were generated using PyMOL. Secondary structure matching (SSM), implemented in Coot, was used to compare the FixK2 structure with other structures of the protein superfamily.

TABLE 1.

Statistics of data collection and structural refinement of native and SeMet-labeled FixK2(C183S)-His6-DNA complexes

SAD, single-wavelength anomalous dispersion; r.m.s.d., root mean square deviation.

| SeMet-Labeled FixK2(C183S)-His6 (SAD data) | Native FixK2(C183S)-His6 | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97961 | 1.00002 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 43.97–3.00 (3.08–3.00) | 43.58–1.77 (1.83–1.77) |

| Space group | P1211 | P1211 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 111.48, 43.97, 69.92 | 111.33, 43.88, 70.11 |

| α, β, γ | 90°, 89.98°, 90° | 90°, 90.04°, 90° |

| Unique reflections | 26,587 (1987)a | 66,473 (6610)a |

| Redundancy | 9.5 (9.5)a | 6.6 (6.8)a |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (100)a | 99.7 (100)a |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 17.08 (4.66)a | 21.82 (3.8)a |

| Refinement | ||

| No. of reflections (work set/test set) | 66,510/3315 | |

| R factorb/Rfreec (%) | 18.30/22.71 | |

| No. of atoms | ||

| Protein (chains A/B) | 1541/1541 | |

| DNA (strands W/X) | 522/478 | |

| Water | 496 | |

| Average B factor (Å2) | ||

| Protein (chains A/B) | 30.7/30.7 | |

| DNA (strands W/X) | 57.2/52.7 | |

| Water | 40.4 | |

| Wilson B factor | 23.76 | |

| r.m.s.d. from ideal | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.018 | |

| Bond angles | 2.064° | |

| Ramachandran plot | ||

| Favored (%) | 98.98 | |

| Allowed regions (%) | 1.02 | |

a Values in parentheses refer to the outermost resolution shell.

b R factor = Σh|Fo − Fc|/Σh|Fo|, where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes for each reflection h.

c Rfree was calculated for a randomly selected 10% of data omitted from refinement.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Problem Solving and Crystallization of FixK2

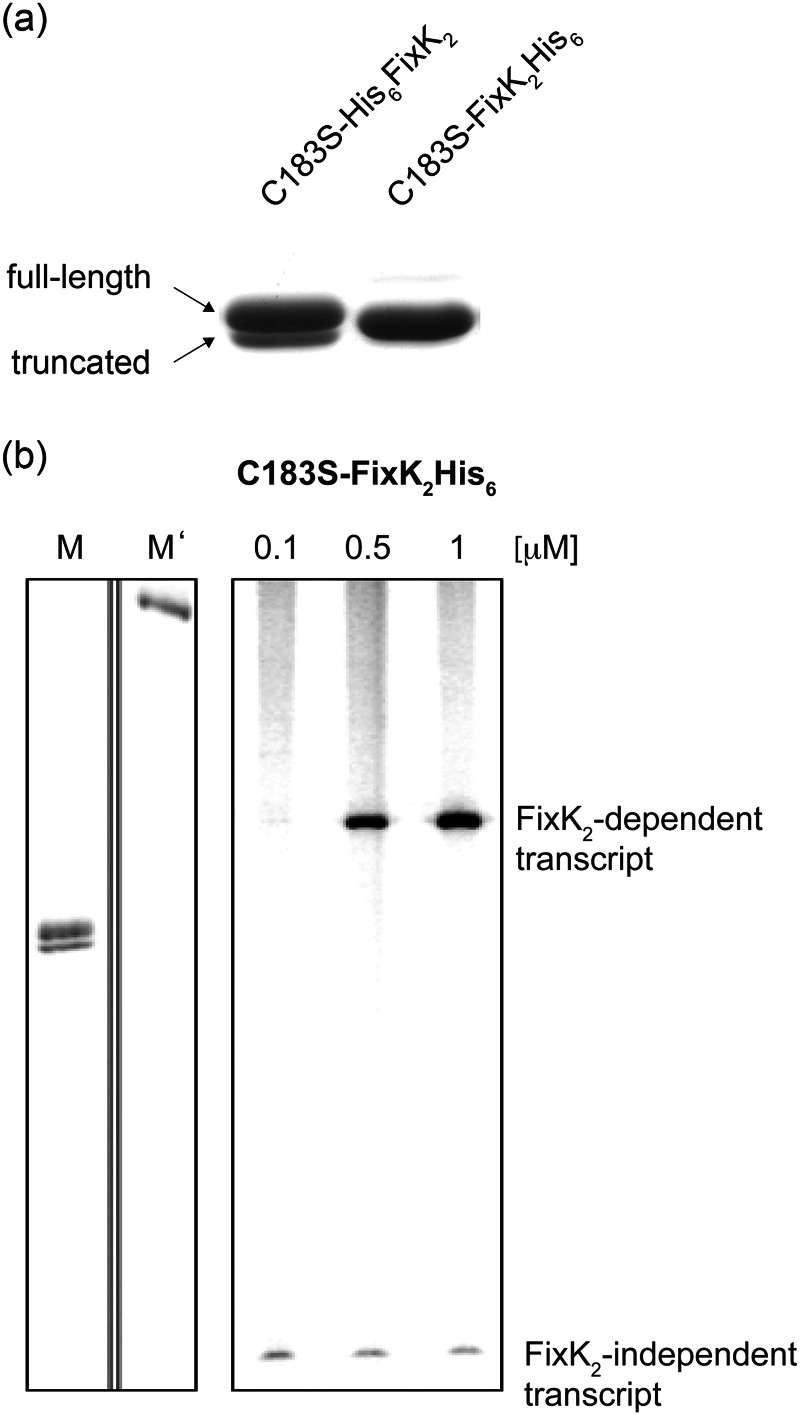

Two major obstacles stood in the way of crystallization of FixK2: the oxidation sensitivity of the protein and its sensitivity to proteolysis. Initially, N-terminally His6-tagged wild-type FixK2 was used, which failed to produce crystals. Static light scattering analyses revealed that the protein solution was highly polydisperse (data not shown), likely reflecting the monomer-dimer equilibrium of FixK2 (18) and the different oxidation states at Cys-183 (19). To avoid oxidation, Cys-183 was exchanged with serine, resulting in the N-terminally His6-tagged construct (His6-FixK2(C183S)). This protein variant was active in an IVT activation assay and resistant to oxidation (data not shown), but it did not crystallize either. Furthermore, His6-FixK2(C183S) copurified with a truncated form, which was identified by mass spectrometry as a 220-amino acid derivative lacking 12 amino acids from the C terminus (named His6-FixK2(C183S)-220) (Fig. 2a). Although this cleaved variant remained soluble, it was inactive in the IVT activation test (data not shown). Exchange of Val-220 and Leu-221 before and after the cleavage site with asparagine or threonine did not abolish cleavage. Cleavage was prevented, however, by using the C-terminally His6-tagged FixK2 variant (FixK2(C183S)-His6). This variant was purified with high yield as an apparently homogeneous full-length protein (molecular mass of 26,883 Da) (Fig. 2a). Despite the relative proximity of the His6 tag to the DNA-binding domain, the FixK2(C183S)-His6 variant was active in the IVT activation assay (Fig. 2b) and was successfully used in subsequent crystallization trials.

FIGURE 2.

Tests for purity and activity of the FixK2(C183S)-His6 protein. a, Coomassie Blue-stained gel after SDS-PAGE of purified N-terminally and C-terminally His6-tagged FixK2(C183S) proteins. The N-terminally tagged construct copurified with a truncated version (His6-FixK2(C183S)-220) that lacks the 12 C-terminal amino acids. b, IVT activation assay with 0.1–1 μm FixK2(C183S)-His6 added to the test mixture. A plasmid template (pRJ8816) containing the FixK2-dependent fixN promoter cloned upstream of a strong transcription terminator was used for multiple-round IVT with RNA polymerase holoenzyme from B. japonicum. A FixK2-independent transcript encoded by the plasmid served as a useful internal control for the RNA polymerase activity. The two left lanes contain RNA size markers with lengths of 180 (M) and 286 (M′) nucleotides.

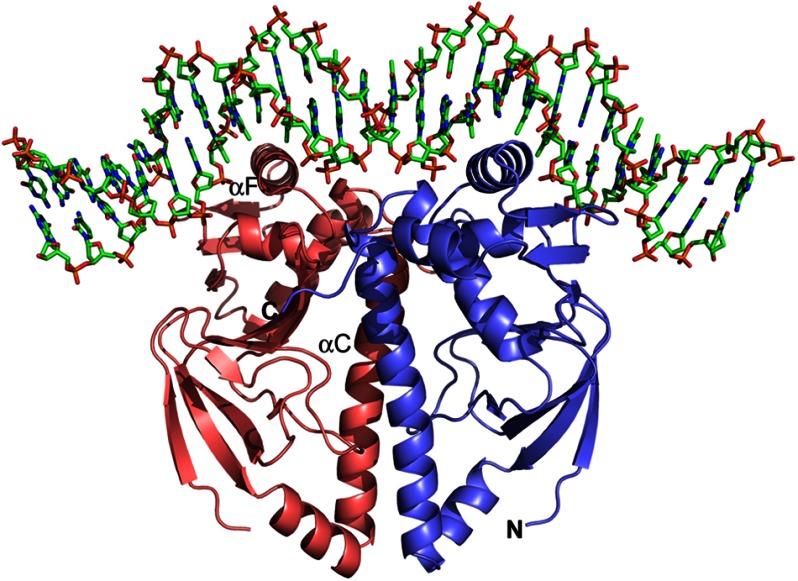

As of today, three structures of proteins from the CRP/FNR family are available in their cofactor-free apo form (6, 10, 12). The majority of the structures available are in complex with their cognate cofactor, and only two structures have the target DNA bound (10, 29). As no cofactor has been identified so far for FixK2, we attempted to crystallize FixK2(C183S)-His6 in the absence and presence of a 30-mer double-stranded target DNA harboring the FixK2-binding site from the promoter of the fixNOQP operon (17). Numerous crystallization conditions and methods, protein concentrations, and temperatures were varied over a broad range, resulting finally in a condition that yielded crystals of FixK2(C183S)-His6 in complex with DNA. The initial crystals diffracted highly anisotropically to a resolution of ∼3 Å. Fine slicing around the pH of the original condition and optimizing the cryo-conditions for plunge freezing resulted in satisfactory crystals (Fig. 1) that diffracted to a resolution of <2 Å. We solved the structure of the FixK2(C183S)-His6-DNA complex by single-wavelength anomalous dispersion and refined it to a final resolution of 1.77 Å, with R factor and Rfree values of 18.3 and 22.7%, respectively (Fig. 3 and Table 1).

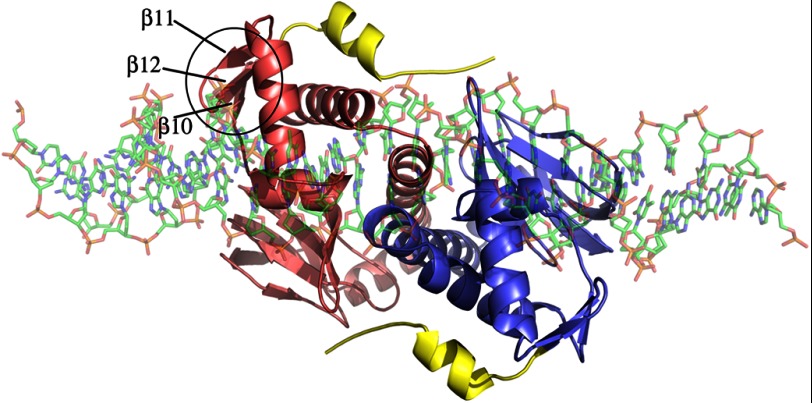

FIGURE 3.

Ribbon representation of the FixK2(C183S)-His6 protein bound to FixK2 box-containing target DNA. The protein-DNA complex crystallized in space group P21. The structure was solved by single-wavelength anomalous dispersion methods and refined to 1.77 Å with R factor and Rfree values of 18.3 and 22.7%, respectively. Due to the lack of electron density at the N terminus, the first 37 amino acids of FixK2(C183S)-His6 could not be modeled. Likewise, a few nucleotides at both ends of the 30-mer DNA could not be structurally determined (see “Experimental Procedures”). The two monomers are shown in red and blue, and some important secondary structure elements have been labeled, i.e. the dimerization helix αC and helix αF from the HTH motif harboring the DNA-binding sequence L195E196XXXR200. The figure was generated using PyMOL.

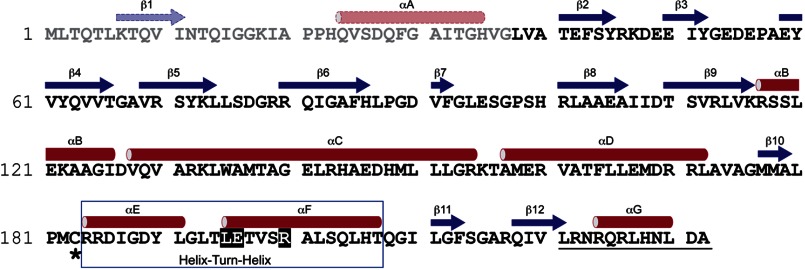

Survey of Structural Features

The electron density map allowed an unequivocal assignment of amino acids 38–232 of the 232-amino acid FixK2 monomer (Fig. 3). Hence, the predicted secondary structure elements β1 and αA in the N-terminal 37-amino acid stretch (Fig. 4) are not visible in the structure. All other secondary structure elements displayed in Fig. 4 have been confirmed by the crystal structure. With the N-terminal region included, each monomer in the dimeric FixK2 protein contains seven α-helices (αA–αG) and 12 β-sheets (β1–β12) (Fig. 4). The full-length protein comprises two major domains: (i) the N-terminal half (residues 1–127: αA–αB and β1–β9) containing the double-stranded β-roll structure (residues 41–116: β2–β9), which in other CRP/FNR family members corresponds to the effector-binding domain, and (ii) the C-terminal DNA-binding domain (residues 155–236: αD–αG and β10–β12) with the winged HTH fold (residues 184–216: αE and αF). The two major domains are connected by the long α-helix (residues 128–154: αC), which is involved in dimerization of the two monomers. The dimeric FixK2(C183S)-His6 structure displays a perfect 2-fold symmetry (Fig. 3). For the DNA molecule, electron density could be seen, and bases were assigned for 25 of 30 nucleotides (strand W) and 24 of 30 nucleotides (strand X). Due to its nearly perfect palindromic sequence, which is interrupted by four nucleotides (TTGAT-N4-ATCAA, with the inverted repeats underlined), the bound DNA molecule displays a quasi-2-fold symmetry.

FIGURE 4.

Secondary structure of FixK2. The secondary structure elements (determined with the software program DSSP using the structure of FixK2(C183S)-His6) are colored red (α-helices) and blue (β-strands). Amino acid residues and secondary structure elements (predicted from the sequence using PSIPred) that are not seen in the solved structure due to the lack of electron density are depicted in lighter colors. Additional structural elements relevant for this work are highlighted as follows: box, HTH motif; white letters, amino acids in the LEXXXR motif of helix αF making contact with DNA at the FixK2 box; asterisk, oxidation-sensitive Cys-183; and underlining, the 12 amino acids that are cleaved off when the C terminus is not protected by a His6 tag.

The overall architecture of the protein-DNA complex with FixK2 is largely similar to that of CRP and CprK (Fig. 5). Nevertheless, the structures do not superimpose ideally, giving relatively high root mean square deviations of 2.08 Å (for 175 Cα atoms) and 3.27 Å (for 177 Cα atoms) for CRP and CprK, respectively. These deviations can be explained primarily by the different arrangement of the DNA portion in the complexes as well as by differences in the C-terminal parts of the proteins.

FIGURE 5.

Superimposition of FixK2(C183S)-His6 (red), CRP (green; Protein Data Bank code 1J59) (14), and CprK (blue; code 3E6C) (10). The overall architecture of the homologous proteins is largely similar, displaying the same overall structural fold. However, CRP and CprK show a stronger DNA bending (90° and 80°, respectively) than FixK2(C183S)-His6 (∼55°).

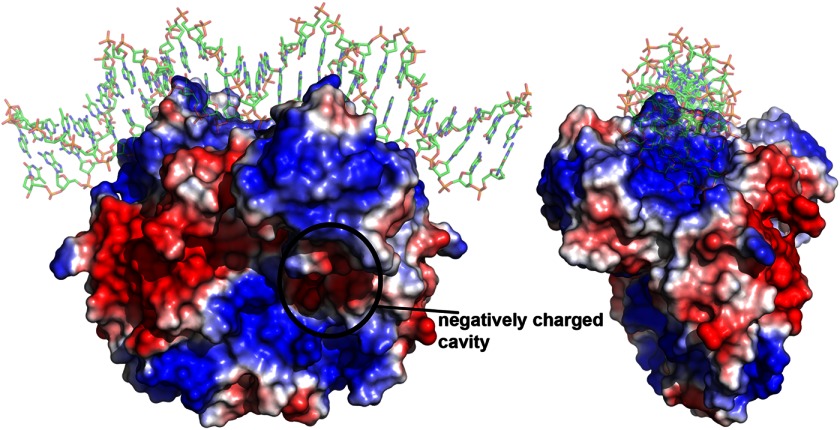

The overall surface of the FixK2 protein appears to exhibit an equal distribution of hydrophobic and hydrophilic patches. A notable surface feature of FixK2 is the presence of one negatively charged cavity per monomer (Fig. 6). Superimposition with CRP showed that this area corresponds to the hydrophobic cAMP-binding pocket in the CRP effector-binding domain. The amino acid residues forming the pockets are not conserved between CRP and FixK2. Although in comparison with CRP, FixK2 must be present in a higher protein concentration to be active in an IVT activation assay, it does not require the addition of a coactivating compound such as cAMP in the case of CRP. Previous work has shown that neither cAMP nor cGMP alters the concentration-dependent elution behavior of FixK2 during size exclusion chromatography (18). Whether or not the aforementioned negatively charged cavity of FixK2 functions in the binding of a yet unidentified cofactor remains an open question. SdrP, another CRP/FNR family member, has also been shown to be active in vitro without any cofactor. SdrP crystallizes in an active form without DNA bound. Contrary to FixK2, however, its crystal structure clearly lacks the putative cofactor-binding pocket (13) because bulky amino acid residues fill the corresponding positions where cAMP occupies the pocket in CRP.

FIGURE 6.

Electrostatic surface of FixK2(C183S)-His6. The structure is shown in two different orientations, related by a 90° rotation along the y axis. Red indicates negatively charged regions (−12 kT/e), and blue indicates positively charged regions (+12 kT/e). Uncharged surfaces are shown in white. The surface shows a negatively charged cavity (encircled) that superimposes well with the cAMP-binding pocket of CRP. The image was generated using the APBS tool in PyMOL.

Surface-exposed C Terminus, a Possible Target for Degradation

As reported above, the N-terminally His6-tagged FixK2(C183S) derivative suffered a truncation during the purification procedure through specific proteolytic cleavage at the C terminus between Val-220 and Leu-221. Moreover, recent work showed that the C terminus in FixK2 is a recognition site for the ClpAP1 chaperone protease, leading to complete degradation of the protein (23). Hence, the C terminus appears to be a critical determinant for protease sensitivity.

The structure of our FixK2-DNA complex now showed that the C-terminal helix (αG) is clearly surface-exposed, rendering the protein susceptible to specific cleavage and ClpAP1-mediated recognition (Fig. 7). Cleavage between Val-220 and Leu-221 disrupts the C-terminal end of β-strand β12 (Fig. 4). Interestingly, β12 is the intermediate β-strand of a small β-sheet formed by β10, β11, and β12 near the DNA-binding domain. Although this β-sheet does not directly interact with the bound DNA (Fig. 7), hydrogen bonds are formed between β12 and αG and between αG and αE of the HTH motif. Therefore, disrupting these hydrogen bonds by proteolytic removal of the last 12 amino acids might affect the DNA-binding domain, leading to inactivation of the protein. In fact, this assumption was confirmed by DNA band shift assays, in which the truncated His6-FixK2(C183S)-220 variant was found to be unable to bind DNA (data not shown), which explains its inactivity in the IVT activation assay (see above).

FIGURE 7.

Top view of the structure of FixK2(C183S)-His6 in complex with DNA. The two monomers are shown in red and blue. The 12 C-terminal amino acids of the protein are colored yellow. They are surface-exposed, rendering the protein accessible to specific proteolytic cleavage and complete degradation. The three β-strands near the protease-sensitive site (β10–β12) are marked on one monomer, and the entire β-sheet is encircled.

The C-terminal helix (αG) is also present in some other members of the CRP/FNR superfamily (CprK (10), PrfA (11), and SdrP (13)) and therein plays a crucial role in DNA binding and activity. In CprK, for example, the C terminus interacts directly with DNA in the on-state but is unstructured in the apo form (10), and in PrfA, the C terminus stabilizes the DNA-binding domain (11). For the latter, mutations of the last helices were found to abolish DNA binding, rendering PrfA inactive (30).

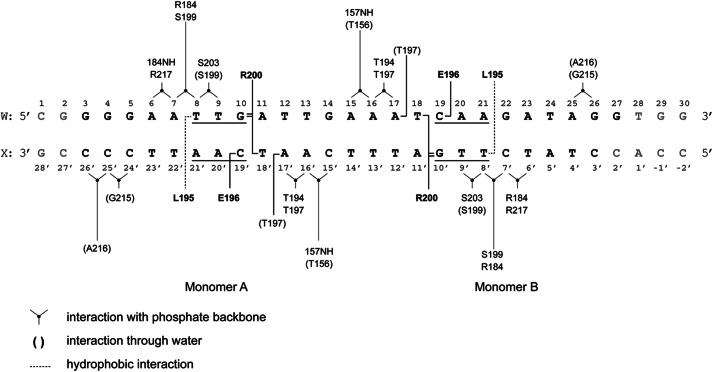

Characteristics of Protein-DNA Interactions

As stated above, only two other structures of the homologs CRP (29) and CprK (10) have been solved in complex with their cognate DNA. The crystallization of FixK2(C183S)-His6 in complex with a cognate target DNA allowed us to gain detailed insight into the interactions between amino acids of the HTH motif and nucleotides of the so-called FixK2 box, a specific and conserved DNA sequence in the promoter region of at least 20 bona fide FixK2-activated genes (18, 19). The FixK2 box consists of 14 bases that include the minimal consensus sequence TTG-N8-CAA. Mutations in the FixK2 box abolish activation of transcription by FixK2 (18). The structure revealed that three amino acids in helix αF (Leu-195, Glu-196, and Arg-200) of the HTH motif directly interact with bases of the FixK2 box (Fig. 8). Leu-195 of either monomer forms a hydrophobic interaction with bases T8 (strand W) and T8′ (strand X). Glu-196 of either monomer forms a hydrogen bond with C19 (strand W) and C19′ on strand X (Fig. 8). Interestingly, the guanidinium moiety of Arg-200 interacts strongly by complex hydrogen bonding with two bases located on different strands of the DNA molecule. Bidentate interactions are formed with G10/G10′, and one additional hydrogen bond is formed with T18′/T18 (monomers A/B) (Figs. 8 and 9). These specific interactions between bases and amino acids are the hallmark of FixK2-DNA binding. Applying bioinformatics analysis, Dufour et al. (31) predicted that the conserved protein sequence (I/L/V)EXXXR applies as a DNA-binding motif for the entire FixK subgroup of all α-proteobacteria. Here, we can perfectly validate this hypothesis because the FixK2-binding motif reads L195E196XXXR200 (Fig. 4). The Arg-200-interacting T18 and T18′ bases are located immediately adjacent to the core consensus sequence TTG-N8-CAA of the previously defined FixK2 box, i.e. they come to lie within the more variable region (N8). Hence, a fourth nucleotide must be considered as being part of the FixK2-interacting DNA, such as TTGA-N6-T18CAA on strand W. To maintain a strong interaction with the FixK2 box, the base at position 18 may alternatively be a G, a requirement imposed by the restricted hydrogen bonding of an arginine side chain to either a T or a G (32). We therefore postulate a refined consensus sequence for the FixK2 box, TTG(A/C)-N6-(T/G)CAA, which coincides reasonably well with the consensus sequence deduced from an alignment of approved FixK2 box-associated promoter sequences (16).

FIGURE 8.

Schematic representation of information on the contact sites between the FixK2 protein and target DNA deduced from the high-resolution structure. Amino acids that undergo specific interactions with nucleotides are indicated by boldface letters. The core FixK2 box is underlined. The gray nucleotides at both ends are those that could not be modeled due to lack of electron density. The types of interactions are indicated in the lower left corner.

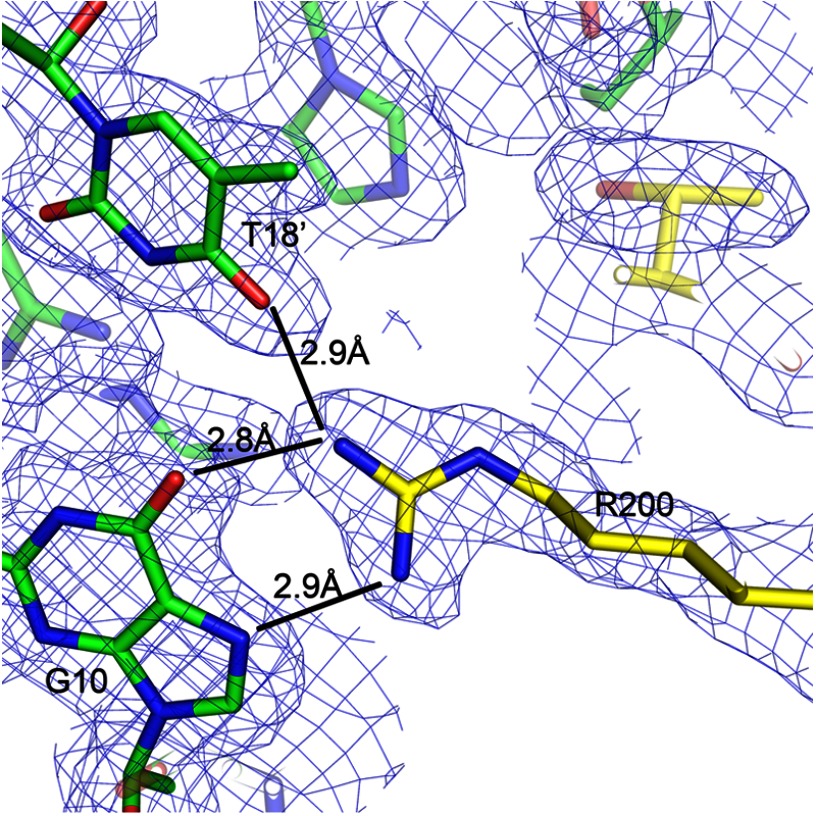

FIGURE 9.

Selected section of the structure around Arg-200 (monomer A) showing the complex hydrogen bond interactions with two bases of opposite DNA strands, i.e. G10 on strand W and T18′ on strand X.

A similar complex protein-DNA interaction network can be found for CRP. As in FixK2, in CRP, the second helix of the HTH motif penetrates the major groove of the DNA, and three conserved specific amino acid side chains (Arg-180, Glu-181, and Arg-185) interact directly via hydrogen bonds with DNA bases, forming an REXXXR motif. These specific residues perfectly superimpose with the LEXXXR binding sequence in FixK2. Despite a similar primary recognition pattern, the DNA in the FixK2 complex structure is less bent (∼55°). In contrast, the observed DNA bend in the CRP complex structure is 90° (Protein Data Bank code 1J59) (14). As in the CRP structure, the DNA bend in the FixK2 structure contains two sharp primary kinks between the pseudo symmetry-related nucleotide pairs T9/G10 and C19/A20 on strand W. Two secondary kinks are also formed on strand W: G3/G4 and A25/G26. In general, the required energy to bend the DNA is compensated by the very specific interactions as described above and between protein side chains and the DNA phosphates. Several indirect protein-DNA interactions were also observed (Fig. 8). These are located in the short loop between the dimerization helices αC and αD as well as in the HTH motif and nearby. The interactions occur through side chain residues and the DNA backbone or via water molecules and, in a few cases, via the amino acid peptide bond and the DNA phosphodiester bond (Fig. 8). These additional interactions, especially the hydrogen bonds located in the inter-αC-αD loop, might contribute to positioning the HTH motif in an appropriate conformation for DNA binding. It has been observed in other CRP/FNR family proteins (CRP, CprK, and NtcA) that the position of αF in the HTH motif and hence its orientation toward the major groove of DNA may change after cofactor binding, which in these proteins is a prerequisite for the association with DNA (10, 12, 15, 29, 33). Although CRP and FixK2 exhibit a similar number of hydrogen bond and ionic interactions between the protein side chains and the DNA phosphates, the ones in CRP are more frequently near the secondary kink, which might explain the stronger bending of bound DNA.

Critical Role of Cys-183 in the Oxidative Control of the FixK2 Protein

One of the regulatory complexes for low-oxygen sensing and signal transduction in B. japonicum is a two-component regulatory system, FixLJ, which controls the activation of the fixK2 gene (17). Once expressed, the FixK2 protein then activates the expression of a large number of genes for microoxic and anoxic energy metabolism (17). Such a sequentially operating cascade of positive controls asks for a negative control that keeps gene expression balanced according to needs. We have previously discovered that ROS negatively interfere with FixK2 by inhibiting its activity through oxidation of the single cysteine at position 183 in the protein (19). Here, we were interested to see if the structure of the FixK2-DNA complex could explain how oxidation of Cys-183 blocks activity.

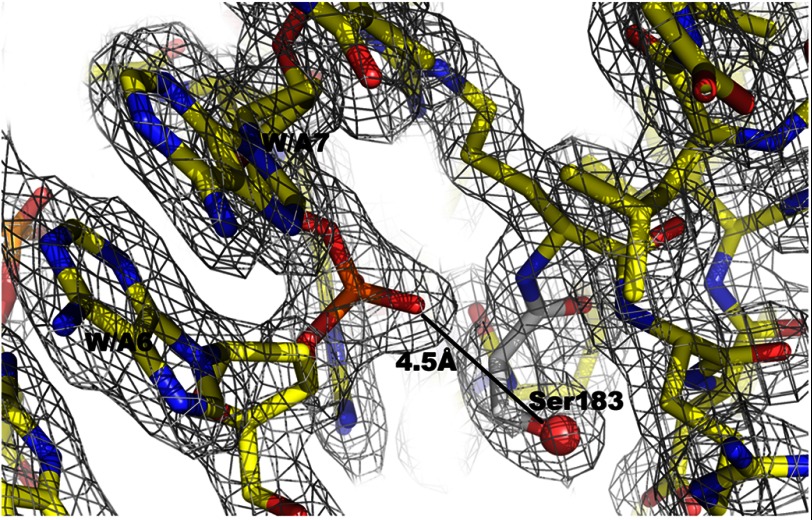

In the crystallized FixK2(C183S) variant, the serine hydroxyl replaces the oxidation-sensitive cysteine thiol. As shown in Fig. 10, Ser-183 is clearly surface-exposed. It is therefore conceivable that Cys-183 in the equivalent position of the wild-type protein is readily accessible for oxidation. In monomer A of the FixK2(C183S) structure, the side chain oxygen of Ser-183 is 4.5 Å away from the phosphodiester between nucleotides A6 and A7 (Fig. 11), which corresponds to the T6′-C7′ phosphate backbone near monomer B. Given that the van der Waals radius of sulfur (1.8 Å) is larger than that of oxygen (1.52 Å) in Ser-183, the Cys-183 thiol is predicted to be even closer to the DNA phosphate backbone. Therefore, Cys-183 might partially fill the space between protein and DNA, yet allowing sufficient distance to the phosphate backbone of DNA.

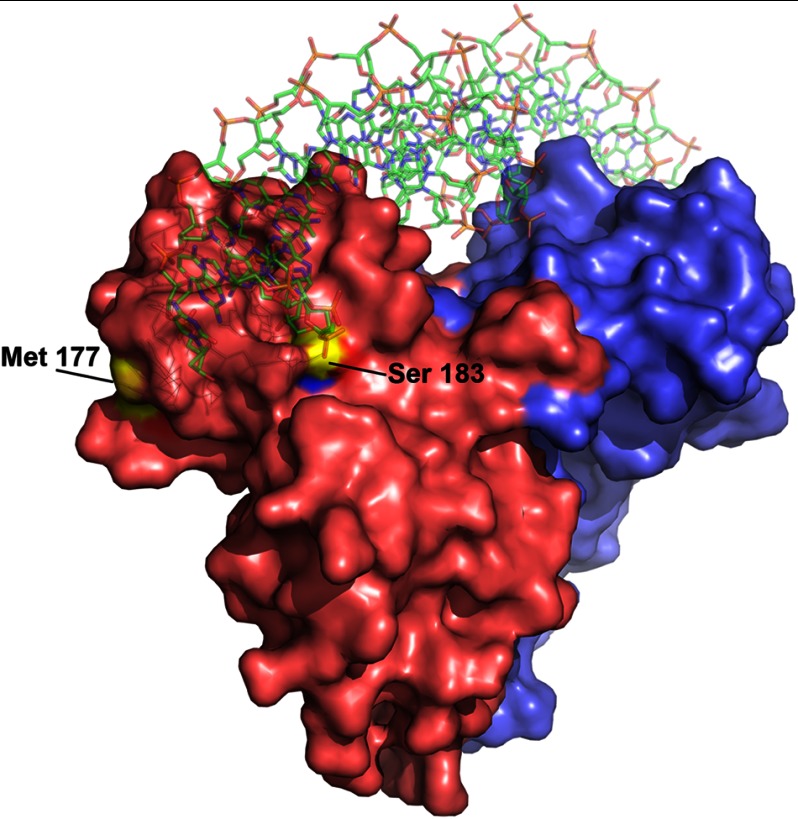

FIGURE 10.

Surface representation of the FixK2(C183S)-His6 protein bound to DNA. The two monomers are shown in red and blue. Ser-183 is surface-exposed and in close proximity to the DNA. In the wild-type protein, oxidation of Cys-183 at this position most likely inactivates the protein through steric hindrance of DNA binding or electrostatic repulsion of the DNA. Met-177 is highlighted as well, being the only one of eight methionines that is located on the surface of the protein. Met-177 is accessible to oxidation, but its oxidation does not influence protein activity.

FIGURE 11.

Selected electron density map. The sector around Ser-183 is shown. The final 2Fo − Fc map is contoured at 1σ and superimposed on the atomic model. The distance to the nearest phosphate of DNA is given.

Upon ROS-mediated oxidation, the conversion of the Cys-183 thiol into sulfinic (–SO2−) or sulfonic (–SO3−) acid derivatives has serious consequences. As a corollary of thiol oxidation, the more bulky negatively charged sulfoxides will cause not only a steric hindrance of the protein-DNA interaction but also an electrostatic repulsion of the opposite negatively charged DNA phosphate, preventing FixK2 binding to DNA or at least DNA bending. However, we cannot completely exclude that such a chemical modification might contribute to a conformational change in the DNA-binding domain, thus resulting in a loss of target DNA recognition.

Previous work has shown that strong overoxidation of FixK2 also affects methionines, which become oxidized to methionine sulfoxides. It was not known, however, how many and which of the eight methionines in each FixK2 monomer had been targeted (19). The structure now shows that only Met-177 is surface-exposed (Fig. 10), which makes it a prime candidate for oxidation in addition to Cys-183. However, because Met-177 is 10 Å away from the nearest DNA phosphate backbone, its irreversible oxidation might not obstruct DNA binding directly. This is corroborated by the fact that treatment of the FixK2(C183A) variant with 0.1 mm hydrogen peroxide, a condition that leads to protein methionine oxidation, does not inhibit the transcription-activating activity of FixK2 (19). Thus, Cys-183 is undoubtedly the most sensitive target, the oxidation of which renders FixK2 inactive.

In conclusion, the surface exposure of the single cysteine residue at position 183 and the proximity of the side chain thiol to DNA when FixK2 is bound to the FixK2 box are the two key features that explain why ROS inhibit this transcription factor post-translationally. Oxidation-sensitive cysteine thiols have also been described for the Desulfitobacterium dehalogenans CprK protein, but these form either intra- or intersubunit disulfide bridges upon oxidation (10). Interestingly, inhibition of a regulatory protein via one cysteine (Cys-179) has recently been described for the B. japonicum OsrA protein, which is an anti-σ-factor of the EcfF σ-factor (34). To the best of our knowledge, our investigation of FixK2 is the first of a member of the CRP/FNR superfamily for which a structural explanation has been found this kind of modification.

Acknowledgments

All data were collected at the Swiss Light Source (Paul Scherrer Institute). We thank the MX group (Swiss Light Source) for outstanding support and B. Blattmann and C. Stutz-Ducommun (Protein Crystallization Center, University of Zürich) for excellent laboratory support during the crystallization.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (to H. H., S. M., and M. G. G.) and by funds from ETH Zürich and University of Zürich. Work in the laboratory of M. G. G. was supported through the framework of the National Center of Competence in Research (NCCR) for Structural Biology.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 4I2O) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- CRP

- cAMP receptor protein

- FNR

- fumarate and nitrate reductase regulator

- HTH

- helix-turn-helix

- IVT

- in vitro transcription

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- SeMet

- selenomethionine

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol.

REFERENCES

- 1. Busby S., Ebright R. H. (1999) Transcription activation by catabolite activator protein (CAP). J. Mol. Biol. 293, 199–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kiley P. J., Beinert H. (1998) Oxygen sensing by the global regulator, FNR: the role of the iron-sulfur cluster. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22, 341–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Körner H., Sofia H. J., Zumft W. G. (2003) Phylogeny of the bacterial superfamily of Crp-Fnr transcription regulators: exploiting the metabolic spectrum by controlling alternative gene programs. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27, 559–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lawson C. L., Swigon D., Murakami K. S., Darst S. A., Berman H. M., Ebright R. H. (2004) Catabolite activator protein: DNA binding and transcription activation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14, 10–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fic E., Bonarek P., Gorecki A., Kedracka-Krok S., Mikolajczak J., Polit A., Tworzydlo M., Dziedzicka-Wasylewska M., Wasylewski Z. (2009) cAMP receptor protein from Escherichia coli as a model of signal transduction in proteins–a review. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 17, 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sharma H., Yu S., Kong J., Wang J., Steitz T. A. (2009) Structure of apo-CAP reveals that large conformational changes are necessary for DNA binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 16604–16609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chin K. H., Lee Y. C., Tu Z. L., Chen C. H., Tseng Y. H., Yang J. M., Ryan R. P., McCarthy Y., Dow J. M., Wang A. H., Chou S. H. (2010) The cAMP receptor-like protein CLP is a novel c-di-GMP receptor linking cell-cell signaling to virulence gene expression in Xanthomonas campestris. J. Mol. Biol. 396, 646–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Giardina G., Castiglione N., Caruso M., Cutruzzolà F., Rinaldo S. (2011) The Pseudomonas aeruginosa DNR transcription factor: light and shade of nitric oxide-sensing mechanisms. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 39, 294–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lanzilotta W. N., Schuller D. J., Thorsteinsson M. V., Kerby R. L., Roberts G. P., Poulos T. L. (2000) Structure of the CO sensing transcription activator CooA. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 876–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Levy C., Pike K., Heyes D. J., Joyce M. G., Gabor K., Smidt H., van der Oost J., Leys D. (2008) Molecular basis of halorespiration control by CprK, a CRP-FNR type transcriptional regulator. Mol. Microbiol. 70, 151–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eiting M., Hagelüken G., Schubert W. D., Heinz D. W. (2005) The mutation G145S in PrfA, a key virulence regulator of Listeria monocytogenes, increases DNA-binding affinity by stabilizing the HTH motif. Mol. Microbiol. 56, 433–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhao M. X., Jiang Y. L., He Y. X., Chen Y. F., Teng Y. B., Chen Y., Zhang C. C., Zhou C. Z. (2010) Structural basis for the allosteric control of the global transcription factor NtcA by the nitrogen starvation signal 2-oxoglutarate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 12487–12492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Agari Y., Kashihara A., Yokoyama S., Kuramitsu S., Shinkai A. (2008) Global gene expression mediated by Thermus thermophilus SdrP, a CRP/FNR family transcriptional regulator. Mol. Microbiol. 70, 60–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Parkinson G., Wilson C., Gunasekera A., Ebright Y. W., Ebright R. E., Berman H. M. (1996) Structure of the CAP-DNA complex at 2.5 angstroms resolution: a complete picture of the protein-DNA interface. J. Mol. Biol. 260, 395–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Popovych N., Tzeng S. R., Tonelli M., Ebright R. H., Kalodimos C. G. (2009) Structural basis for cAMP-mediated allosteric control of the catabolite activator protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 6927–6932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mesa S., Hauser F., Friberg M., Malaguti E., Fischer H. M., Hennecke H. (2008) Comprehensive assessment of the regulons controlled by the FixLJ-FixK2-FixK1 cascade in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J. Bacteriol. 190, 6568–6579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nellen-Anthamatten D., Rossi P., Preisig O., Kullik I., Babst M., Fischer H. M., Hennecke H. (1998) Bradyrhizobium japonicum FixK2, a crucial distributor in the FixLJ-dependent regulatory cascade for control of genes inducible by low oxygen levels. J. Bacteriol. 180, 5251–5255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mesa S., Ucurum Z., Hennecke H., Fischer H. M. (2005) Transcription activation in vitro by the Bradyrhizobium japonicum regulatory protein FixK2. J. Bacteriol. 187, 3329–3338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mesa S., Reutimann L., Fischer H. M., Hennecke H. (2009) Posttranslational control of transcription factor FixK2, a key regulator for the Bradyrhizobium japonicum-soybean symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 21860–21865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pauly N., Pucciariello C., Mandon K., Innocenti G., Jamet A., Baudouin E., Hérouart D., Frendo P., Puppo A. (2006) Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and glutathione: key players in the legume-Rhizobium symbiosis. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 1769–1776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chang C., Damiani I., Puppo A., Frendo P. (2009) Redox changes during the legume-rhizobium symbiosis. Mol. Plant 2, 370–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Santos R., Hérouart D., Sigaud S., Touati D., Puppo A. (2001) Oxidative burst in alfalfa-Sinorhizobium meliloti symbiotic interaction. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 14, 86–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bonnet M., Stegmann M., Maglica Ž., Stiegeler E., Weber-Ban E., Hennecke H., Mesa S. (2013) FixK2, a key regulator in Bradyrhizobium japonicum, is a substrate for the protease ClpAP in vitro. FEBS Lett. 587, 88–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kabsch W. (2010) XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schneider T. R., Sheldrick G. M. (2002) Substructure solution with SHELXD. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58, 1772–1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Davis I. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L. W., Kapral G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., Richardson J. S., Terwilliger T. C., Zwart P. H. (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schultz S. C., Shields G. C., Steitz T. A. (1991) Crystal structure of a CAP-DNA complex: the DNA is bent by 90 degrees. Science 253, 1001–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Herler M., Bubert A., Goetz M., Vega Y., Vazquez-Boland J. A., Goebel W. (2001) Positive selection of mutations leading to loss or reduction of transcriptional activity of PrfA, the central regulator of Listeria monocytogenes virulence. J. Bacteriol. 183, 5562–5570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dufour Y. S., Kiley P. J., Donohue T. J. (2010) Reconstruction of the core and extended regulons of global transcription factors. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Luscombe N. M., Laskowski R. A., Thornton J. M. (2001) Amino acid-base interactions: a three-dimensional analysis of protein-DNA interactions at an atomic level. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 2860–2874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Passner J. M., Steitz T. A. (1997) The structure of a CAP-DNA complex having two cAMP molecules bound to each monomer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 2843–2847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Masloboeva N., Reutimann L., Stiefel P., Follador R., Leimer N., Hennecke H., Mesa S., Fischer H. M. (2012) Reactive oxygen species-inducible ECF σ factors of Bradyrhizobium japonicum. PLoS ONE 7, e43421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]