Abstract

The tumor suppressor function of the promyelocytic leukemia (PML) protein was first identified as a result of its dysregulation in acute promyelocytic leukemia, however, its importance is now emerging far beyond hematological neoplasms, to an extensive range of malignancies, including solid tumors. In response to stress signals, PML coordinates the regulation of numerous proteins, which activate fundamental cellular processes that suppress tumorigenesis. Importantly, PML itself is the subject of specific post-translational modifications, including ubiquitination, phosphorylation, acetylation, and SUMOylation, which in turn control PML activity and stability and ultimately dictate cellular fate. Improved understanding of the regulation of this key tumor suppressor is uncovering potential opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Targeting the key negative regulators of PML in cancer cells such as casein kinase 2, big MAP kinase 1, and E6-associated protein, with specific inhibitors that are becoming available, provides unique and exciting avenues for restoring tumor suppression through the induction of apoptosis and senescence. These approaches could be combined with DNA damaging drugs and cytokines that are known to activate PML. Depending on the cellular context, reactivation or enhancement of tumor suppressive PML functions, or targeted elimination of aberrantly functioning PML, may provide clinical benefit.

Keywords: PML, E6AP, BMK1, CK2, KLHL20, tumour suppression, targeted anti-cancer therapy, small molecule inhibitors

Introduction

The promyelocytic leukemia (PML) gene was initially described in the pathogenesis of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL), where it fuses with the Retinoic Acid Receptor α (RARα) gene as a consequence of the chromosomal translocation t(15;17). The resultant PML-RARα fusion oncoprotein acts in a dominant negative fashion over wild type (wt) PML, as reiterated in a mouse model (Rego and Pandolfi, 2001); where malignancy manifests from a differentiation blockage of granulocyte precursors which is compounded by an enhanced self-renewal (de Thé and Chen, 2010). All-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and arsenic trioxide (As2O3) were empirically identified to provoke a profound therapeutic response against APL, before the molecular pathogenesis of the disease was established (Huang et al., 1988; Borrow et al., 1990; de Thé et al., 1990; Sun et al., 1992) and unravelling intricacies of their mode of action toward PML-RARα is ongoing. The intense research that followed the landmark discovery linking PML to APL pathogenesis, revealed that PML acts as a tumor suppressor in many other cancer types and is a master regulator of major cellular processes.

Promyelocytic leukemia comprises multiple isoforms, which predominantly localize to the nucleus (Bernardi and Pandolfi, 2007; Carracedo et al., 2011). In response to various stress signals, PML forms distinct matrix-associated structures in the nucleoplasm, called PML nuclear bodies (NBs) (otherwise known as PML-NBs, POD, ND10) (Bernardi and Pandolfi, 2007; Carracedo et al., 2011). Over 70 proteins are known to co-localize with PML in the NBs, mainly in a transient manner (Bernardi and Pandolfi, 2007; Carracedo et al., 2011). PML-NBs mediate the post-translational modification of target proteins and in a spatio-temporal manner coordinate a diverse range of specific cellular functions, including gene transcription, DNA repair, apoptosis, senescence, and anti-viral response (Dellaire and Bazett-Jones, 2004; Geoffroy and Chelbi-Alix, 2011). In APL, the expression of PML-RARα is associated with numerous, disorganized nuclear microstructures instead of the normal PML-NBs (Koken et al., 1994; Weis et al., 1994).

A well-defined downstream effector pathway of PML (Salomoni et al., 2008, 2012) involves the key tumor suppressor p53. In response to stress, PML promotes the activation and stabilization of p53 by protecting it from its major inhibitor Mdm2, and facilitating key post-translational modifications (Louria-Hayon et al., 2003; Bernardi et al., 2004; Alsheich-Bartok et al., 2008). Intriguingly, PML is also a transcriptional target of p53 (de Stanchina et al., 2004), implying that these two important tumor suppressors impact on each other through a positive regulatory loop. However, transcription is not the major dictator of altered PML levels (Gurrieri et al., 2004a) and in this review, we scrutinize our current knowledge regarding PML regulation. We suggest that the careful analysis of key upstream molecules that act upon PML in different cancer types will be a strategic approach toward rationally defining targets for the design of specific anti-cancer therapies with a capacity to restore functional PML.

Loss of PML Function Promotes Tumorigenesis

The original studies by Koken et al. (1995) and Terris et al. (1995) revealed that PML expression is altered during the process of oncogenic transformation. In the subsequent studies PML protein levels were identified to be down-regulated (complete or partial loss) in a wide spectrum of human cancers, beyond APL, including additional hematological neoplasms: non-Hodgkin lymphomas (77%), carcinomas of the: prostate (92%), lung (58%), colon (47%); and breast (53%); tumors of the central nervous system (CNS; 73%) and germ cells (85%) (Gurrieri et al., 2004a); stomach (Lee et al., 2007), lung small cells (Zhang et al., 2000); and sarcomas of the soft tissues (Vincenzi et al., 2010). Pertinently, downregulation of PML is frequently associated with increased tumor grade and highly aggressive disease in some tumor types, e.g., prostate and breast adenocarcinomas (Rego and Pandolfi, 2001). PML tumor suppressive functions have been validated in a number of genetically engineered mouse cancer models. PML deficiency in the context of PTEN+/− mice, resulted in the invasive adenocarcinoma of the colon (Trotman et al., 2006). Dosage-dependent PML loss correlated with the number and size of colonic polyps. Further, the tumor burden and aggressiveness of KrasG12D-induced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) was significantly increased in the absence of PML (Scaglioni et al., 2006). Most recently, PML tumor suppressive capacity was demonstrated in a mouse model of B-lymphoma driven by c-Myc (Wolyniec et al., 2012b) and in the context of mutant p53 (Haupt et al., 2013). These fundamental in vivo studies, together with detailed molecular analysis in vitro, have revealed major roles of PML in the induction of apoptosis and cellular senescence.

Multiple Mechanisms of PML Regulation

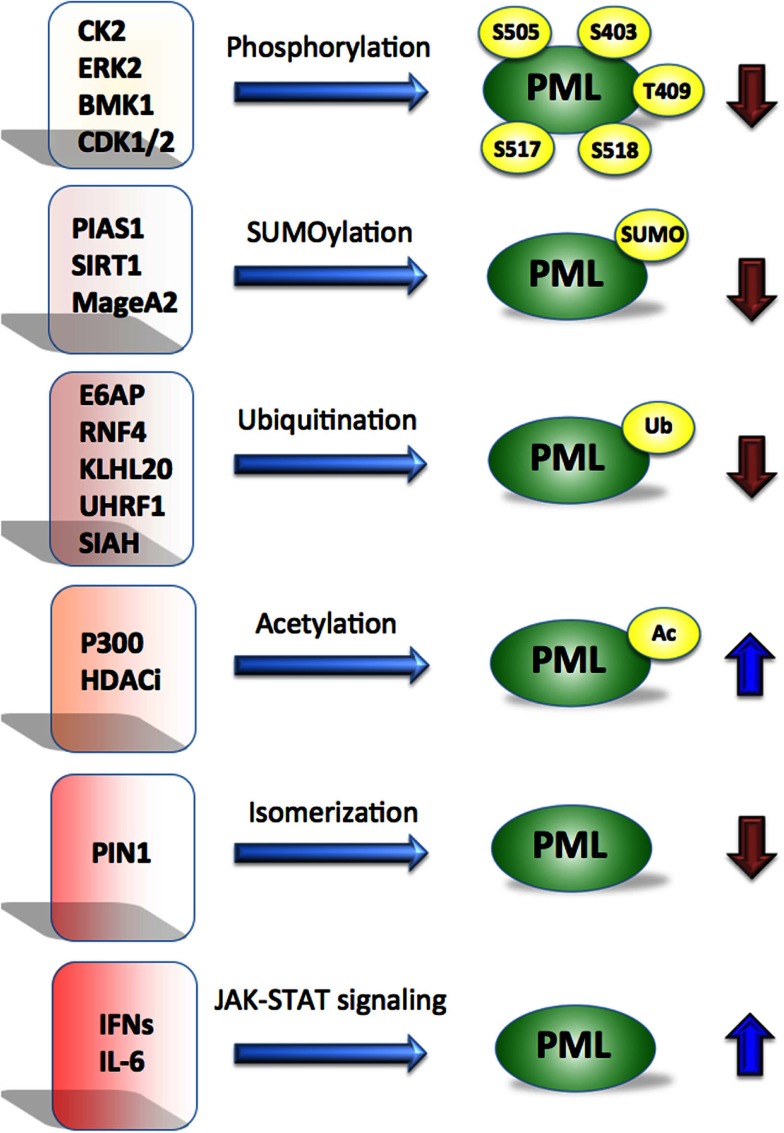

Loss of PML protein frequently occurs in cancers without correlation to PML mRNA levels, or gene mutation, but rather at a post-translational level (Gurrieri et al., 2004a,b). Importantly, proteasome inhibitor treatment of selected tumor cell lines lacking detectable PML levels (Gurrieri et al., 2004a), was able to restore PML expression. This provided a rationale for restoration of PML expression at the protein level. Molecular pathways that promote PML degradation are therefore potential targets for its restoration. Further, PML degradation is regulated by post-translational modifications including ubiquitination, phosphorylation, acetylation, SUMOylation, and isomerization (Figure 1); and each of these pathways has been implicated in various types of cancer (Table 1) and offers therapeutic potential.

Figure 1.

Promyelocytic leukemia is regulated by multiple mechanisms. Post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation, SUMOylation, ubiquitination, acetylation, isomerization by indicated proteins affect PML stability. Cytokines such as IFNs and IL-6 are known to activate PML at the transcriptional level via JAK-STAT signaling. Blue arrows indicate positive and brown negative effect on PML.

Table 1.

Summary of PML modifications implicated in various human cancers.

| Type of PML modification | Cancer type | PML gain (+) or loss(−) | Reference | Section in the text |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitination by E6AP | B-cell lymphoma | − | Wolyniec et al. (2012b) | Section “Ubiquitination” |

| Phosphorylation by CK2 | NSCL cancer | − | Scaglioni et al. (2006) | Section “Phosphorylation” |

| SUMOylation by PIAS1 | NSCL cancer | − | Rabellino et al. (2012) | Section “SUMOylation” |

| Ubiquitination by KLHL20 | Prostate cancer | − | Yuan et al. (2011) | Section “Ubiquitination” |

| Phosphorylation by ERK2/Pin1 | Breast cancer | − | Lim et al. (2011) | Section “Phosphorylation” |

| Unknown mechanism | Breast cancer | + | Carracedo et al. (2012) | Section “Targeting GOF PML Activities in Non-Hematopoietic Malignancies” |

| Mutant p53 context | Colon cancer | + | Haupt et al. (2009) | Section “Targeting GOF PML Activities in Non-Hematopoietic malignancies” |

Reference to the section in the text and to the original publication is listed.

Ubiquitination

The finding that PML expression is largely regulated in cancer cells at the level of proteasomal degradation (Gurrieri et al., 2004a) triggered a search for the relevant E3 ligases that regulate the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of PML in normal and cancer cells. In cancer cells the normal regulation of PML turnover is likely to become corrupted leading to destabilization of PML as a mechanism of evading tumor suppression (Chen et al., 2012b). E3 ligases able to promote the degradation of PML-RARα are also of obvious therapeutic value.

In a search for the key E3 ligase of PML we found that the E6-associated protein (E6AP) is a physiological E3 ubiquitin ligase of PML, and showed increased PML expression in multiple tissues of E6AP KO mice. One of the functional implications of this finding was that lymphoid cells derived from E6AP deficient mice were more susceptible to DNA-damage induced apoptosis, associated with enhanced accumulation of PML-NBs (Louria-Hayon et al., 2009). A more direct demonstration linking the E6AP-PML axis to cancer was evident in our recent study of Myc-driven B-cell lymphoma. We found that a loss of one E6AP allele was sufficient to attenuate B lymphomagenesis through the restoration of PML expression and induction of cellular senescence. Importantly, E6AP levels were elevated and associated with PML downregulation in more than half of the human B-cell lymphomas examined (Wolyniec et al., 2012b).

Another E3 ligase that is frequently elevated in various cancers is UHRF1 (ubiquitin-like with PHD and RING finger domains). UHRF1 was demonstrated to target PML for degradation by mediating its polyubiquitination in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) and cancer cell lines (Guan et al., 2012). The ubiquitin ligase ring finger protein 4 (RNF4) selectively targets poly-SUMOylated PML (see SUMOylation) (Lallemand-Breitenbach et al., 2008; Tatham et al., 2008). This process is a key mechanism of action of As2O3 resulting in the degradation of PML and PML-RARα in APL (see Targeting PML-RARα to Treat Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia). In addition to proteasomal degradation, autophagy also mediates the degradation of PML-RARα induced by ATRA and As2O3 (Boe and Simonsen, 2010). The ubiquitin-binding adaptor protein p62/SQSTM1 recognizes specific poly-ubiquitinated proteins including PML-RARα and directs them to autophagosomes for degradation (Pankiv et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2011).

In vitro studies have demonstrated that the RING finger E3 ligase SIAH-1/2 binds the coil–coil domain of PML, via its substrate-binding domain (SBD), and promotes the proteasomal degradation of PML and PML-RARα (Fanelli et al., 2004). An interesting study by Yuan et al., revealed a crucial role for the substrate adaptor protein KLHL20 of the Cullin 3-based ubiquitin ligase, in the regulation of PML in response to hypoxia, during tumor progression of prostate cancer. HIF-1α was found to induce KLHL20 promoting the ubiquitination and degradation of PML (Yuan et al., 2011).

Phosphorylation

Coordinated phosphorylation and isomerization appears to be a prerequisite for ubiquitin-mediated destruction of PML, a process involving a number of kinases. In response to hypoxia (as mentioned in see Ubiquitination), induction of KLHL20 by HIF-1α results in PML turnover. This requires the prior coordinated phosphorylation of PML by CDK1/2, followed by isomerization of the phosphorylated PML by the peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase, Pin1. This cascade is involved in cell transformation, migration, angiogenesis, and survival of mouse xenografts in vivo. Most importantly, the HIF-1α/KLHL20/Pin1 axis is upregulated in high grade aggressive and chemoresistant human prostate lesions and correlated with PML loss (Yuan et al., 2011).

Another example of this sequential PML preconditioning occurs with the extracellular signal regulated kinase 2 (ERK2), which is able to localize to the PML-NBs in breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231), phosphorylate PML at two sites (S403 and S505), resulting in the recruitment of Pin1, and subsequent proteasomal degradation of PML by yet to be identified E3 ligase (Lim et al., 2011). Addition of hydrogen peroxide was capable of attenuating the association between PML and Pin1 to maintain PML levels. On the other hand, IGF-1 reduced PML levels in a Pin1 dependent manner, which enhanced cell migration (Reineke et al., 2010). Although ERK2 and Pin1 are frequently elevated in many cancers, the link to reduced PML levels in vivo is yet to be demonstrated.

Phosphorylation priming of PML has also been described without associated isomerization, however whether this second event is also important remains to be addressed. PML phosphorylation at multiple sites by casein kinase 2 (CK2), was shown by the elegant work of Scaglioni et al. (2006), to promote its proteasomal degradation, although the identity of the ubiquitin E3 ligase that is involved remains to be discovered. Further, analysis of NSCLC patient derived samples and cell lines, revealed that reduced PML levels directly correlated with increased CK2 activity, consistent with the relevance of this pathway to lung tumorigenesis (Scaglioni et al., 2006). Big MAP kinase 1 (BMK1) also phosphorylates PML at two sites: S403 and T409 (Yang et al., 2010). Mutational analysis demonstrated that BMK1 drives suppression of PML directly through its phosphorylation. Activation of BMK1 by its upstream MEK5 kinase results in the translocation of BMK1 from the cytosol to the PML-NBs (Yang et al., 2010). It was further demonstrated that activated BMK1 interferes with the formation of PML-Mdm2 complex, resulting in the suppression of p53 (Yang et al., 2012).

Acetylation

The acetylation of PML represents an additional post-translation mechanism regulating PML. Treatment of HeLa cells with the HDAC (histone deacetylase) inhibitor, trichostatin A (TSA) resulted in increased acetylation of PML leading to efficient induction of apoptosis (Hayakawa et al., 2008). Importantly an acetylation-defective PML mutant renders cells refractory to HDAC inhibitor-induced cell death. The acetylation of PML could be enhanced by p300 acetylase. Interestingly the increase of PML acetylation was associated with the increase in the SUMOylation (Hayakawa et al., 2008). Hence it has been suggested that acetylation of PML may be a prerequisite for subsequent SUMOylation. It remains to be shown whether activation of PML by new generation HDAC inhibitors, currently under investigation, represents a key molecular event associated with clinical response.

SUMOylation

The addition of small ubiquitin-like molecule (SUMO) to PML is essential for PML-NB formation and maturation, and may also mark PML for ubiquitination. SUMO may either be non-covalently bound to PML through the SUMO binding domain (Shen et al., 2006), or covalently attached by an E1, E2, and E3-ligase enzymatic cascade (Shen et al., 2006). PML SUMOylation also facilitates the recruitment of partner proteins to NBs and in turn their own SUMOylation (Shen et al., 2006; Bernardi and Pandolfi, 2007). Support of SUMOylation as key modification of PML is based on a number of studies. (Campagna et al., 2011) described a novel function for the histone deacetylase, SIRT1, in facilitating PML SUMOylation. The melanoma antigen gene A2, MageA2, interacts with PML isoform IV and significantly attenuates the SUMOylation and acetylation of PML, which in turn affects p53-mediated cellular senescence (Peche et al., 2012). The E3 SUMO ligase, protein inhibitor of activated STAT-1 (PIAS1), SUMOylates PML, and promotes the recruitment of CK2 to phosphorylate PML on S517 and consequently its degradation (Peche et al., 2012). PIAS1 regulates PML in NSCL cancer (Peche et al., 2012), and it has been implicated in As2O3-mediated degradation of PML-RARα in APL (Rabellino et al., 2012). Overall, the studies described above suggest a cascade of post-translational modifications involving phosphorylation, isomerization, and SUMOylation, regulating PML turnover (Chen et al., 2012b).

Cytokine-dependent regulation of PML

There is growing evidence highlighting the importance of paracrine signaling in the regulation of PML whereby its transcription is controlled by interferons (IFNs), specific cytokines involved in anti-viral responses, immune-surveillance as well as anti-proliferative processes, which are known to be potent inducers of PML (Chelbi-Alix et al., 1995; Lavau et al., 1995; Stadler et al., 1995; Der et al., 1998). For example, IFNβ has been recently shown to induce cellular senescence, a key anti-cancer mechanism, via a PML-induced mechanism (Chiantore et al., 2012). In addition, genotoxic drugs such as etoposide trigger cellular senescence in normal and cancer cells via persistent activation of Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) signaling and expression of IFN-stimulated genes including PML (Hubackova et al., 2010; Novakova et al., 2010). This is particularly interesting in the context of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which constitutes an integral part of the paracrine/autocrine regulation of tumor suppression. Furthermore, PML was recently shown to be regulated by interleukin-6 (IL-6) through a molecular signaling pathway mediated by NFκB and JAK-STAT (Hubackova et al., 2012). Since IL-6 is a prototypical cytokine involved in cellular senescence, it is tempting to speculate that PML and IL-6 exist in a positive regulatory loop driving oncogenic and DNA-damage induced senescence. This would in turn lead to secretion of IL-6 and IFNs that would further sustain activation of PML.

Therapies to Restore PML Tumor Suppression

A strategic approach to treating malignancies in which PML tumor suppressor activity has been reduced or lost through aberrant degradation, is to target those degradation pathways. However, in some contexts corrupted PML may provide a survival mechanism for disease and therapeutic benefit may result from its inhibition and will be discussed in Section “Therapies to Target Oncogenic PML Activities.”

Therapies directed to inhibiting PML ubiquitination

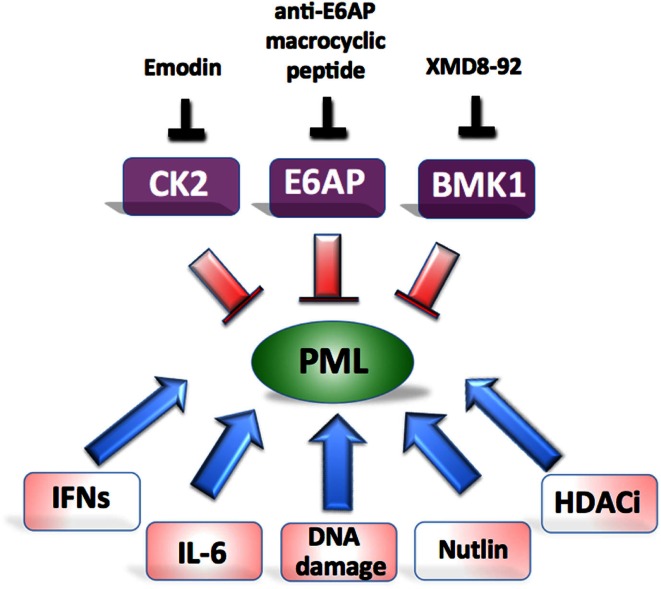

In our recent study we demonstrated that E6AP elevation is frequently found in human B-cell lymphomas and is associated with PML downregulation (Wolyniec et al., 2012b). By using Myc-induced mouse model of lymphomagenesis and human B-cell lymphoma cell lines, we demonstrated that E6AP haploinsufficiency in mice or siRNA mediated inhibition of E6AP in human cells, is sufficient to restrain tumor development by inducing PML-dependent cellular senescence and preventing expansion of pre-leukemic B-cells. These observations provide the basis for considering E6AP as a promising anti-cancer target (Figure 2). Interestingly, a natural product-like macrocyclic N-methyl peptide inhibitor against E6AP has been synthesized by random non-standard peptides integrated discovery (RaPID) (Yamagishi et al., 2011). This peptide inhibitor, or other inhibitors of E6AP, can be used to test the possibility of relieving PML from proteasomal destruction in cancers where E6AP is elevated such as prostate adenocarcinoma and B-lymphoma (Srinivasan and Nawaz, 2011; Wolyniec et al., 2012b). Another therapeutic strategy could be to target Culin-3/KLHL20 mediated PML ubiquitination using a recently described Cullin-family E3 ligase inhibitor, MLN4924 (Soucy et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2012b). Although this inhibitor has been shown to exhibit potent anti-cancer activity by targeting NEDD8, it remains to be demonstrated whether PML is also involved in this mechanism.

Figure 2.

Potential approaches aiming at restoration of PML-induced tumor suppression. Major therapeutic targets and their inhibitors are shown on top and potential combinatorial treatments at the bottom.

Therapy directed to inhibiting PML phosphorylation

Scaglioni et al. (2006) demonstrated that the reactivation of PML in vivo could be achieved in established lung cancer xenotransplants, with emodin, a pharmacological inhibitor of CK2 kinase (Figure 2). Although emodin exerts its effect through multiple pathways, this approach resulted in substantial suppression of growth that could be attributed to specific elevation of PML. Emodin treatment has previously been shown to increase the sensitivity of HeLa cells to As2O3 cytotoxicity through the generation of ROS, however the role of PML was not explored in this model (Yi et al., 2004).

Another very convincing strategy aimed at restoration of PML tumor suppression has been described in the elegant study by Yang et al. (2010) (Figure 2). By using a newly developed BMK1 inhibitor (XMD8-92), the authors were able to demonstrate efficient anti-tumor effect in vitro and in multiple xenotransplants in vivo, which was achieved by specific restoration of PML and downstream activation of p21. In their subsequent study they provided detailed explanation for the mechanism of BMK1 inhibitor by linking it to p53 activation (Yang et al., 2012).

Combinatorial therapies to promote PML activation

Importantly, PML stability can be greatly enhanced by genotoxic drugs and HDAC inhibitors as well as cytokines such as IL-6 and IFNs. Therefore it is very likely that the right combinations of various PML activating strategies may translate to effective therapeutic outcomes (Figure 2). For example, treatment of cancer cells with etoposide triggers PML-induced senescence by engaging JAK/STAT pathway (Hubackova et al., 2010). This provides a rationale for a combination treatment of cancer cells with agents to stabilize PML such as emodin, XMD8-92, or anti-E6AP N-methyl peptide combined with DNA damaging agents and pro-senescence cytokines (Acosta and Gil, 2012). Such an approach should enhance cancer cell death but still requires formal testing. Our studies and others strongly support a link between PML and p53 whereby these proteins exist in a positive regulatory loop (Louria-Hayon et al., 2003; Bernardi et al., 2004; Alsheich-Bartok et al., 2008). Therefore the combined approach of restoring PML together with p53 (e.g., by using nutlin) should be tested. The tailoring of PML therapies to target multiple defined genetic malfunctions in individual cancers offers an exciting novel approach to inhibit cancer cell growth.

Therapies to Target Oncogenic PML Activities

Targeting PML-RARα to treat acute promyelocytic leukemia

Generation of the PML-RARα oncogenic fusion protein disrupts the normal functions of PML and RARα and is the driving pathogenic event in APL (de Thé et al., 1991; Rego et al., 2000; de Thé and Chen, 2010). PML-RARα impairs the assembly of PML-NBs and represses the expression of key regulatory genes involved in myeloid differentiation (Daniel et al., 1993; Zhu et al., 2002).

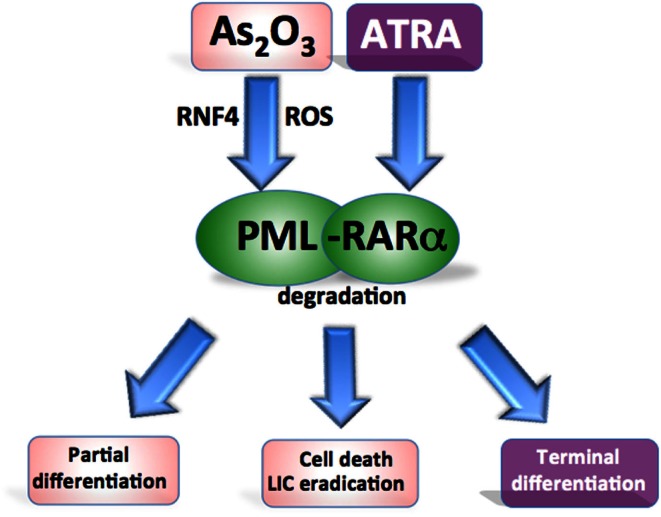

As2O3 and ATRA have been extensively used in the clinic as anti-APL therapy and have the overlapping effect of targeting and inducing the degradation of the PML-RARα fusion protein, thereby overcoming the differentiation block and restoring the senescence program in APL cells (Chen et al., 1997; Shao et al., 1998; Ferbeyre, 2002) (Figure 3). As2O3 is highly effective in the treatment APL and superior to ATRA in terms of its ability to achieve molecular remissions. As2O3 has been used as a single agent, and in combination with ATRA and chemotherapy achieving long term disease-free survival in up to 90% of APL patients (Hu et al., 2009; Ravandi et al., 2009; Mathews et al., 2010; Powell et al., 2010; Ghavamzadeh et al., 2011; Iland et al., 2012).

Figure 3.

Targeting oncogenic PML in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Both agents target the PML-RARα fusion protein for degradation. ATRA promotes RARα-target gene transcription to overcome the differentiation block while As2O3 induces oxidant stress and directly binds PML to cause partial differentiation and apoptosis of APL cells and more effectively eradicate leukemia-initiating cells.

All-trans retinoic acid and As2O3 have the effect of restoring the normal distribution pattern of the PML associated NBs in APL (Koken et al., 1994; Weis et al., 1994; Muller et al., 1998b). In contrast to the NB reorganization induced by ATRA, As2O3 also causes swelling of the structures followed by a loss of PML staining. This may be the result of As2O3 inducing the attachment of multiple SUMO-1 molecules to PML (Muller et al., 1998a,b). As2O3 targets PML to induce degradation of both the PML-RARα fusion protein and PML (Lallemand-Breitenbach et al., 2012). The action of As2O3 is attributed to a combination of direct binding to PML and a more general oxidant effect (Jeanne et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010) (Figure 3). The inherent high ROS levels of APL cells contribute to their sensitivity to As2O3 (Yi et al., 2002; Li et al., 2008). Direct arsenic binding to PML results in topological changes in the RING domain enhancing the binding of the SUMO-conjugating enzyme (Jeanne et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010). As2O3 treatment also induces phosphorylation of the PML protein through a mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathway, which promotes efficient SUMOylation of PML (Hayakawa and Privalsky, 2004). Poly-SUMOylated PML is recognized by the SUMO-dependent ubiquitin ligase RNF4, poly-ubiquitinated, and degraded (Lallemand-Breitenbach et al., 2008; Tatham et al., 2008). Furthermore, As2O3 also induces apoptosis via oxidant stress (Miller et al., 2002).

Targeting GOF PML activities in non-hematopoietic malignancies

Beyond APL, we have reported another example of what appears to be PML gain of function (GOF). In the background of mutant p53, PML tumor suppression cannot only be lost, but its activities can be conscripted to provide growth advantage. In fact, when PML was knocked down in these cancer cells they lapsed into growth arrest (Haupt et al., 2009). It is in this context that arsenic trioxide treatment of mutant p53 cancer cells is interesting, because although the drug has been demonstrated to target mutant p53 for proteasomal degradation (Yan et al., 2011), the activity against PML in this context has yet to be demonstrated, and neither has the consequence for cell viability.

Interestingly, PML was recently found to be elevated in a subpopulation of triple negative breast cancer patients and this correlated with reduced survival and poor prognosis (Carracedo et al., 2012). The functional studies revealed that in this context PML was able to simultaneously inhibit acetylation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPARγ) co-activator 1A and activate PPAR signaling and fatty acid oxidation, which resulted in increased ATP. It will be critical to define the PML profile in these breast cancers where gain of pro-survival functions is apparent and fascinating to explore whether PML targeted therapy such as As2O3 has an application in these specific cancers. In addition, targeting the pathways activated by this elevated PML (i.e., fatty acid oxidation) may hold promise for therapy. However, targeting this pathway will need careful consideration as it is also involved in PML-dependent hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) maintenance (Ito et al., 2012).

Targeting elevated levels of PML to eradicate leukemic stem cells

Promyelocytic leukemia plays a key role in the maintenance of HSCs and leukemia-initiating cells (LICs) (Ito et al., 2008). Murine Pml−/− HSCs are not quiescent in the bone marrow of recipient mice and lacked long term repopulating capacity following transplantation. LICs share features of HSCs such as self-renewal, pluripotency, and quiescence (Reya et al., 2001; Hope et al., 2004; Holtz et al., 2007).

Quiescent chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) stem cells are resistant to conventional therapy including Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitors and can be a source of relapse (Holtz et al., 2007). Unlike many other hematological malignancies, PML is highly expressed in CML particularly in more primitive CD34 positive cells (Ito et al., 2008). Indeed PML expression is an adverse prognostic factor in CML and being investigated as a potential therapeutic target in this disease. In a CML mouse model, Pml−/− LICs undergo intensive cycling resulting in impairment of LIC maintenance and, in contrast to Pml wt cells, failed to initiate a CML-like disease after serial bone marrow transplantation procedures (Ito et al., 2008). By down-regulating PML, As2O3 also induces cell cycling of quiescent LICs and enhances cytarabine-mediated apoptosis to eradicate these cells in a serial transplantation model (Ito et al., 2008).

Future Directions

Over the last decade, immense progress has been made regarding our understanding of molecular pathways regulating PML stability. Major post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation, acetylation, SUMOylation, and ubiquitination and their interactions have been extensively studied in normal and cancer cells. Although we have identified certain kinases and E3 ubiquitin ligases of PML, less is known about potential phosphatases and deubiquitinases, which are likely to play important regulatory functions. Another key limitation in our understanding of PML is the shortage of information about isoform specific effects and the potential problem with protecting and activating cancer promoting or cancer suppressing proteins. Hence, the new generation of mouse models specific for PML isoforms will be absolutely necessary to address these important issues. Treating of APL patients with As2O3 is usually very effective as it specifically targets the pathogenic PML-RARα fusion protein for degradation and reactivates functional PML. However, there is a proportion of APL patient that remains resistant and therefore novel therapies are required. Clearly, the restoration of PML to inhibit cancer growth emerges as a promising targeted strategy (Wolyniec et al., 2012a) that could be applied to many cancer types, given that PML plays a central tumor suppressive role in a wider range of human cancers than previously appreciated. Importantly it could be combined with currently used therapies such as chemotherapy, IFN, or IL-6 treatment, which are known to induce PML. Pertinently currently there are emerging several potentially druggable targets such as CK2, BMK1, KLHL20, and E6AP that has been demonstrated to negatively regulate PML stability in various pre-clinical cancer models. Further studies are required to evaluate the anti-cancer efficiency of the specific inhibitors of these molecules such as XMD8-92 in multiple pre-clinical models and eventually in clinical trials. However, there is a caveat concerning targeting of BMK1, related to the recent finding reporting that inhibition of BMK1 can stimulate EMT and cell migration (Chen et al., 2012a). As illustrated in this review one needs to carefully consider tissue type, genetic background, and stage of the disease in order to trigger PML for the benefit of patients with minimal possible side-effects. It becomes apparent that PML is regulated by different molecules in different cancer types, e.g., by E6AP in B-cell lymphoma (Wolyniec et al., 2012b), CK2, and PIAS1 in NSCL cancer (Scaglioni et al., 2006; Rabellino et al., 2012) whereas KLHL20/Pin1 in prostate adenocarcinoma (Yuan et al., 2011).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Due to space limitations, many original important studies have not been cited directly but rather through recent reviews. Ygal Haupt is supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia (NHMRC #1026988, #1026999, and 1049179), by a grant from the CASS Foundation, the Victorian Cancer Agency (CAPTIV), PCF, Cancer Council Victoria, and by the VESKI award. Ygal Haupt is NHMRC Senior Research Fellow (NHMRC#628426). The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Acosta J. C., Gil J. (2012). Senescence: a new weapon for cancer therapy. Trends Cell Biol. 22, 211–219 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsheich-Bartok O., Haupt S., Alkalay-Snir I., Saito S., Appella E., Haupt Y. (2008). PML enhances the regulation of p53 by CK1 in response to DNA damage. Oncogene 27, 3653–3661 10.1038/sj.onc.1211036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi R., Pandolfi P. P. (2007). Structure, dynamics and functions of promyelocytic leukaemia nuclear bodies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 1006–1016 10.1038/nrm2277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi R., Scaglioni P. P., Bergmann S., Horn H. F., Vousden K. H., Pandolfi P. P. (2004). PML regulates p53 stability by sequestering Mdm2 to the nucleolus. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 665–672 10.1038/ncb1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boe S. O., Simonsen A. (2010). Autophagic degradation of an oncoprotein. Autophagy 6, 964–965 10.4161/auto.6.7.13066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrow J., Goddard A. D., Sheer D., Solomon E. (1990). Molecular analysis of acute promyelocytic leukemia breakpoint cluster region on chromosome 17. Science 249, 1577–1580 10.1126/science.2218500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campagna M., Herranz D., Garcia M. A., Marcos-Villar L., Gonzalez-Santamaria J., Gallego P., et al. (2011). SIRT1 stabilizes PML promoting its sumoylation. Cell Death Differ. 18, 72–79 10.1038/cdd.2010.77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carracedo A., Ito K., Pandolfi P. P. (2011). The nuclear bodies inside out: PML conquers the cytoplasm. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23, 360–366 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carracedo A., Weiss D., Leliaert A. K., Bhasin M., de Boer V. C., Laurent G., et al. (2012). A metabolic prosurvival role for PML in breast cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 3088–3100 10.1172/JCI62129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelbi-Alix M. K., Pelicano L., Quignon F., Koken M. H., Venturini L., Stadler M., et al. (1995). Induction of the PML protein by interferons in normal and APL cells. Leukemia 9, 2027–2033 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G. Q., Shi X. G., Tang W., Xiong S. M., Zhu J., Cai X., et al. (1997). Use of arsenic trioxide (As2O3) in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). I. As2O3 exerts dose-dependent dual effects on APL cells. Blood 89, 3345–3353 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Yang Q., Lee J. D. (2012a). BMK1 kinase suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition through the Akt/GSK3beta signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 72, 1579–1587 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R. H., Lee Y. R., Yuan W. C. (2012b). The role of PML ubiquitination in human malignancies. J. Biomed. Sci. 19, 81. 10.1186/1423-0127-19-81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiantore M. V., Vannucchi S., Accardi R., Tommasino M., Percario Z. A., Vaccari G., et al. (2012). Interferon-beta induces cellular senescence in cutaneous human papilloma virus-transformed human keratinocytes by affecting p53 transactivating activity. PLoS ONE 7:e36909. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Daniel M. T., Koken M., Romagne O., Barbey S., Bazarbachi A., Stadler M., et al. (1993). PML protein expression in hematopoietic and acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Blood 82, 1858–1867 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Stanchina E., Querido E., Narita M., Davuluri R. V., Pandolfi P. P., Ferbeyre G., et al. (2004). PML is a direct p53 target that modulates p53 effector functions. Mol. Cell 13, 523–535 10.1016/S1097-2765(04)00062-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Thé H., Chen Z. (2010). Acute promyelocytic leukaemia: novel insights into the mechanisms of cure. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 775–783 10.1038/nrc2943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Thé H., Chomienne C., Lanotte M., Degos L., Dejean A. (1990). The t(15;17) translocation of acute promyelocytic leukaemia fuses the retinoic acid receptor alpha gene to a novel transcribed locus. Nature 347, 558–561 10.1038/347558a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Thé H., Lavau C., Marchio A., Chomienne C., Degos L., Dejean A. (1991). The PML-RAR alpha fusion mRNA generated by the t(15;17) translocation in acute promyelocytic leukemia encodes a functionally altered RAR. Cell 66, 675–684 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90113-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellaire G., Bazett-Jones D. P. (2004). PML nuclear bodies: dynamic sensors of DNA damage and cellular stress. Bioessays 26, 963–977 10.1002/bies.20089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Der S. D., Zhou A., Williams B. R., Silverman R. H. (1998). Identification of genes differentially regulated by interferon alpha, beta, or gamma using oligonucleotide arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 15623–15628 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanelli M., Fantozzi A., de Luca P., Caprodossi S., Matsuzawa S., Lazar M. A., et al. (2004). The coiled-coil domain is the structural determinant for mammalian homologues of Drosophila Sina-mediated degradation of promyelocytic leukemia protein and other tripartite motif proteins by the proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 5374–5379 10.1074/jbc.M306407200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferbeyre G. (2002). PML a target of translocations in APL is a regulator of cellular senescence. Leukemia 16, 1918–1926 10.1038/sj.leu.2402722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geoffroy M. C., Chelbi-Alix M. K. (2011). Role of promyelocytic leukemia protein in host antiviral defense. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 31, 145–158 10.1089/jir.2010.0111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghavamzadeh A., Alimoghaddam K., Rostami S., Ghaffari S. H., Jahani M., Iravani M., et al. (2011). Phase II study of single-agent arsenic trioxide for the front-line therapy of acute promyelocytic leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 2753–2757 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan D., Factor D., Liu Y., Wang Z., Kao H. Y. (2012). The epigenetic regulator UHRF1 promotes ubiquitination-mediated degradation of the tumor-suppressor protein promyelocytic leukemia protein. Oncogene. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1038/onc.2012.406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurrieri C., Capodieci P., Bernardi R., Scaglioni P. P., Nafa K., Rush L. J., et al. (2004a). Loss of the tumor suppressor PML in human cancers of multiple histologic origins. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 96, 269–279 10.1093/jnci/djh043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurrieri C., Nafa K., Merghoub T., Bernardi R., Capodieci P., Biondi A., et al. (2004b). Mutations of the PML tumor suppressor gene in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 103, 2358–2362 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt S., DI Agostino S., Mizrahi I., Alsheich-Bartok O., Voorhoeve M., Damalas A., et al. (2009). Promyelocytic leukemia protein is required for gain of function by mutant p53. Cancer Res. 69, 4818–4826 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt S., Mitchell C., Corneille V., Shortt J., Fox S., Pandolfi P. P., et al. (2013). Loss of PML cooperates with mutant p53 to drive more aggressive cancers in a gender dependent manner. Cell Cycle (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa F., Abe A., Kitabayashi I., Pandolfi P. P., Naoe T. (2008). Acetylation of PML is involved in histone deacetylase inhibitor-mediated apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 24420–24425 10.1074/jbc.M802217200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa F., Privalsky M. L. (2004). Phosphorylation of PML by mitogen-activated protein kinases plays a key role in arsenic trioxide-mediated apoptosis. Cancer Cell 5, 389–401 10.1016/S1535-6108(04)00082-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtz M., Forman S. J., Bhatia R. (2007). Growth factor stimulation reduces residual quiescent chronic myelogenous leukemia progenitors remaining after imatinib treatment. Cancer Res. 67, 1113–1120 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope K. J., Jin L., Dick J. E. (2004). Acute myeloid leukemia originates from a hierarchy of leukemic stem cell classes that differ in self-renewal capacity. Nat. Immunol. 5, 738–743 10.1038/ni1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., Liu Y. F., Wu C. F., Xu F., Shen Z. X., Zhu Y. M., et al. (2009). Long-term efficacy and safety of all-trans retinoic acid/arsenic trioxide-based therapy in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 3342–3347 10.1073/pnas.0907872106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M. E., Ye Y. C., Chen S. R., Chai J. R., Lu J. X., Zhoa L., et al. (1988). Use of all-trans retinoic acid in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 72, 567–572 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubackova S., Krejcikova K., Bartek J., Hodny Z. (2012). Interleukin 6 signaling regulates promyelocytic leukemia protein gene expression in human normal and cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 26702–26714 10.1074/jbc.M111.316869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubackova S., Novakova Z., Krejcikova K., Kosar M., Dobrovolna J., Duskova P., et al. (2010). Regulation of the PML tumor suppressor in drug-induced senescence of human normal and cancer cells by JAK/STAT-mediated signaling. Cell Cycle 9, 3085–3099 10.4161/cc.9.15.12521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iland H. J., Bradstock K., Supple S. G., Catalano A., Collins M., Hertzberg M., et al. (2012). All-trans-retinoic acid, idarubicin, and IV arsenic trioxide as initial therapy in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APML4). Blood 120, 1570–1580 10.1182/blood-2012-02-410746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K., Bernardi R., Morotti A., Matsuoka S., Saglio G., Ikeda Y., et al. (2008). PML targeting eradicates quiescent leukaemia-initiating cells. Nature 453, 1072–1078 10.1038/nature07016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K., Carracedo A., Weiss D., Arai F., Ala U., Avigan D. E., et al. (2012). A PML-PPAR-delta pathway for fatty acid oxidation regulates hematopoietic stem cell maintenance. Nat. Med. 18, 1350–1358 10.1038/nm.2882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanne M., Lallemand-Breitenbach V., Ferhi O., Koken M., LE Bras M., Duffort S., et al. (2010). PML/RARA oxidation and arsenic binding initiate the antileukemia response of As2O3. Cancer Cell 18, 88–98 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koken M. H., Linares-Cruz G., Quignon F., Viron A., Chelbi-Alix M. K., Sobczak-Thepot J., et al. (1995). The PML growth-suppressor has an altered expression in human oncogenesis. Oncogene 10, 1315–1324 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koken M. H., Puvion-Dutilleul F., Guillemin M. C., Viron A., Linares-Cruz G., Stuurman N., et al. (1994). The t(15;17) translocation alters a nuclear body in a retinoic acid-reversible fashion. EMBO J. 13, 1073–1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallemand-Breitenbach V., Jeanne M., Benhenda S., Nasr R., Lei M., Peres L., et al. (2008). Arsenic degrades PML or PML-RARalpha through a SUMO-triggered RNF4/ubiquitin-mediated pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 547–555 10.1038/ncb1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallemand-Breitenbach V., Zhu J., Chen Z., de Thé H. (2012). Curing APL through PML/RARA degradation by As2O3. Trends Mol. Med. 18, 36–42 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavau C., Marchio A., Fagioli M., Jansen J., Falini B., Lebon P., et al. (1995). The acute promyelocytic leukaemia-associated PML gene is induced by interferon. Oncogene 11, 871–876 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. E., Jee C. D., Kim M. A., Lee H. S., Lee Y. M., Lee B. L., et al. (2007). Loss of promyelocytic leukemia protein in human gastric cancers. Cancer Lett. 247, 103–109 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Wang J., Ye R. D., Shi G., Jin H., Tang X., et al. (2008). PML/RARalpha fusion protein mediates the unique sensitivity to arsenic cytotoxicity in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells: mechanisms involve the impairment of cAMP signaling and the aberrant regulation of NADPH oxidase. J. Cell. Physiol. 217, 486–493 10.1002/jcp.21507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J. H., Liu Y., Reineke E., Kao H. Y. (2011). Mitogen-activated protein kinase extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 phosphorylates and promotes Pin1 protein-dependent promyelocytic leukemia protein turnover. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 44403–44411 10.1074/jbc.M110.210724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louria-Hayon I., Alsheich-Bartok O., Levav-Cohen Y., Silberman I., Berger M., Grossman T., et al. (2009). E6AP promotes the degradation of the PML tumor suppressor. Cell Death Differ. 16, 1156–1166 10.1038/cdd.2009.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louria-Hayon I., Grossman T., Sionov R. V., Alsheich O., Pandolfi P. P., Haupt Y. (2003). The promyelocytic leukemia protein protects p53 from Mdm2-mediated inhibition and degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 33134–33141 10.1074/jbc.M301264200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews V., George B., Chendamarai E., Lakshmi K. M., Desire S., Balasubramanian P., et al. (2010). Single-agent arsenic trioxide in the treatment of newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia: long-term follow-up data. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 3866–3871 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.5031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. H., Jr., Schipper H. M., Lee J. S., Singer J., Waxman S. (2002). Mechanisms of action of arsenic trioxide. Cancer Res. 62, 3893–3903 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller S., Matunis M. J., Dejean A. (1998a). Conjugation with the ubiquitin-related modifier SUMO-1 regulates the partitioning of PML within the nucleus. EMBO J. 17, 61–70 10.1093/emboj/17.1.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller S., Miller W. H., Jr., Dejean A. (1998b). Trivalent antimonials induce degradation of the PML-RAR oncoprotein and reorganization of the promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies in acute promyelocytic leukemia NB4 cells. Blood 92, 4308–4316 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novakova Z., Hubackova S., Kosar M., Janderova-Rossmeislova L., Dobrovolna J., Vasicova P., et al. (2010). Cytokine expression and signaling in drug-induced cellular senescence. Oncogene 29, 273–284 10.1038/onc.2009.318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankiv S., Clausen T. H., Lamark T., Brech A., Bruun J. A., Outzen H., et al. (2007). p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 24131–24145 10.1074/jbc.M702824200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peche L. Y., Scolz M., Ladelfa M. F., Monte M., Schneider C. (2012). MageA2 restrains cellular senescence by targeting the function of PMLIV/p53 axis at the PML-NBs. Cell Death Differ. 19, 926–936 10.1038/cdd.2011.173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell B. L., Moser B., Stock W., Gallagher R. E., Willman C. L., Stone R. M., et al. (2010). Arsenic trioxide improves event-free and overall survival for adults with acute promyelocytic leukemia: North American Leukemia Intergroup Study C9710. Blood 116, 3751–3757 10.1182/blood-2010-02-269621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabellino A., Carter B., Konstantinidou G., Wu S. Y., Rimessi A., Byers L. A., et al. (2012). The SUMO E3-ligase PIAS1 regulates the tumor suppressor PML and its oncogenic counterpart PML-RARA. Cancer Res. 72, 2275–2284 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravandi F., Estey E., Jones D., Faderl S., O’Brien S., Fiorentino J., et al. (2009). Effective treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with all-trans-retinoic acid, arsenic trioxide, and gemtuzumab ozogamicin. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 504–510 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rego E. M., He L. Z., Warrell R. P., Jr., Wang Z. G., Pandolfi P. P. (2000). Retinoic acid (RA) and As2O3 treatment in transgenic models of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) unravel the distinct nature of the leukemogenic process induced by the PML-RARalpha and PLZF-RARalpha oncoproteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 10173–10178 10.1073/pnas.180290497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rego E. M., Pandolfi P. P. (2001). Analysis of the molecular genetics of acute promyelocytic leukemia in mouse models. Semin. Hematol. 38, 54–70 10.1053/shem.2001.20865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reineke E. L., Liu Y., Kao H. Y. (2010). Promyelocytic leukemia protein controls cell migration in response to hydrogen peroxide and insulin-like growth factor-1. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 9485–9492 10.1074/jbc.M109.063362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reya T., Morrison S. J., Clarke M. F., Weissman I. L. (2001). Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature 414, 105–111 10.1038/35102167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomoni P., Dvorkina M., Michod D. (2012). Role of the promyelocytic leukaemia protein in cell death regulation. Cell Death Dis. 3, e247. 10.1038/cddis.2011.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomoni P., Ferguson B. J., Wyllie A. H., Rich T. (2008). New insights into the role of PML in tumour suppression. Cell Res. 18, 622–640 10.1038/cr.2008.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaglioni P. P., Yung T. M., Cai L. F., Erdjument-Bromage H., Kaufman A. J., Singh B., et al. (2006). A CK2-dependent mechanism for degradation of the PML tumor suppressor. Cell 126, 269–283 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao W., Fanelli M., Ferrara F. F., Riccioni R., Rosenauer A., Davison K., et al. (1998). Arsenic trioxide as an inducer of apoptosis and loss of PML/RAR alpha protein in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 90, 124–133 10.1093/jnci/90.2.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen T. H., Lin H. K., Scaglioni P. P., Yung T. M., Pandolfi P. P. (2006). The mechanisms of PML-nuclear body formation. Mol. Cell 24, 331–339 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucy T. A., Smith P. G., Milhollen M. A., Berger A. J., Gavin J. M., Adhikari S., et al. (2009). An inhibitor of NEDD8-activating enzyme as a new approach to treat cancer. Nature 458, 732–736 10.1038/nature07884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan S., Nawaz Z. (2011). E3 ubiquitin protein ligase, E6-associated protein (E6-AP) regulates PI3K-Akt signaling and prostate cell growth. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1809, 119–127 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler M., Chelbi-Alix M. K., Koken M. H., Venturini L., Lee C., Saib A., et al. (1995). Transcriptional induction of the PML growth suppressor gene by interferons is mediated through an ISRE and a GAS element. Oncogene 11, 2565–2573 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H. D., Ma L., Hu X. C., Zhang T. D. (1992). Ai-Lin I treated 32 cases of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Chin. J. Integr. Chin. West. Med. 12, 170–171 [Google Scholar]

- Tatham M. H., Geoffroy M. C., Shen L., Plechanovova A., Hattersley N., Jaffray E. G., et al. (2008). RNF4 is a poly-SUMO-specific E3 ubiquitin ligase required for arsenic-induced PML degradation. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 538–546 10.1038/ncb1716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terris B., Baldin V., Dubois S., Degott C., Flejou J. F., Henin D., et al. (1995). PML nuclear bodies are general targets for inflammation and cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 55, 1590–1597 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotman L. C., Alimonti A., Scaglioni P. P., Koutcher J. A., Cordon-Cardo C., Pandolfi P. P. (2006). Identification of a tumour suppressor network opposing nuclear Akt function. Nature 441, 523–527 10.1038/nature04809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincenzi B., Perrone G., Santini D., Grosso F., Silletta M., Frezza A., et al. (2010). PML down-regulation in soft tissue sarcomas. J. Cell. Physiol. 224, 644–648 10.1002/jcp.22161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Cao L., Kang R., Yang M., Liu L., Zhao Y., et al. (2011). Autophagy regulates myeloid cell differentiation by p62/SQSTM1-mediated degradation of PML-RARalpha oncoprotein. Autophagy 7, 401–411 10.4161/auto.7.9.15863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis K., Rambaud S., Lavau C., Jansen J., Carvalho T., Carmo-Fonseca M., et al. (1994). Retinoic acid regulates aberrant nuclear localization of PML-RARα in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Cell 76, 345–356 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90341-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolyniec K., Chan A. L., Haupt S., Haupt Y. (2012a). Restoring PML tumor suppression to combat cancer. Cell Cycle 11, 3705–3706 10.4161/cc.22043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolyniec K., Shortt J., de Stanchina E., Levav-Cohen Y., Alsheich-Bartok O., Louria-Hayon I., et al. (2012b). E6AP ubiquitin ligase regulates PML-induced senescence in Myc-driven lymphomagenesis. Blood 120, 822–832 10.1182/blood-2011-10-387647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi Y., Shoji I., Miyagawa S., Kawakami T., Katoh T., Goto Y., et al. (2011). Natural product-like macrocyclic N-methyl-peptide inhibitors against a ubiquitin ligase uncovered from a ribosome-expressed de novo library. Chem. Biol. 18, 1562–1570 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan W., Zhang Y., Zhang J., Liu S., Cho S. J., Chen X. (2011). Mutant p53 protein is targeted by arsenic for degradation and plays a role in arsenic-mediated growth suppression. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 17478–17486 10.1074/jbc.M110.192708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q., Deng X., Lu B., Cameron M., Fearns C., Patricelli M. P., et al. (2010). Pharmacological inhibition of BMK1 suppresses tumor growth through promyelocytic leukemia protein. Cancer Cell 18, 258–267 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q., Liao L., Deng X., Chen R., Gray N. S., Yates J. R., III, et al. (2012). BMK1 is involved in the regulation of p53 through disrupting the PML-MDM2 interaction. Oncogene. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1038/onc.2012.332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi J., Gao F., Shi G., Li H., Wang Z., Shi X., et al. (2002). The inherent cellular level of reactive oxygen species: one of the mechanisms determining apoptotic susceptibility of leukemic cells to arsenic trioxide. Apoptosis 7, 209–215 10.1023/A:1015331229263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi J., Yang J., He R., Gao F., Sang H., Tang X., et al. (2004). Emodin enhances arsenic trioxide-induced apoptosis via generation of reactive oxygen species and inhibition of survival signaling. Cancer Res. 64, 108–116 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-2820-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan W. C., Lee Y. R., Huang S. F., Lin Y. M., Chen T. Y., Chung H. C., et al. (2011). A cullin3-KLHL20 ubiquitin ligase-dependent pathway targets PML to potentiate HIF-1 signaling and prostate cancer progression. Cancer Cell 20, 214–228 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P., Chin W., Chow L. T., Chan A. S., Yim A. P., Leung S. F., et al. (2000). Lack of expression for the suppressor PML in human small cell lung carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 85, 599–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. W., Yan X. J., Zhou Z. R., Yang F. F., Wu Z. Y., Sun H. B., et al. (2010). Arsenic trioxide controls the fate of the PML-RARalpha oncoprotein by directly binding PML. Science 328, 240–243 10.1126/science.1183424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Chen Z., Lallemand-Breitenbach V., de Thé H. (2002). How acute promyelocytic leukaemia revived arsenic. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 705–713 10.1038/nrc887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]