Abstract

Cardiovascular autonomic imbalance and breathing instability are major contributors to the progression of heart failure (CHF). Potentiation of the carotid body (CB) chemoreflex has been shown to contribute to these effects. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) recently has been proposed to mediate CB hypoxic chemoreception. We hypothesized that H2S synthesis inhibition should decrease CB chemoreflex activation and improve breathing stability and autonomic function in CHF rats. Using the irreversible inhibitor of cystathione γ-lyase dl-propargylglycine (PAG), we tested the effects of H2S inhibition on resting breathing patterns, the hypoxic and hypercapnic ventilatory responses, and the hypoxic sensitivity of CB chemoreceptor afferents in rats with CHF. In addition, heart rate variability (HRV) and systolic blood pressure variability (SBPV) were calculated as an index of autonomic function. CHF rats, compared with sham rats, exhibited increased breath interval variability and number of apneas, enhanced CB afferent discharge and ventilatory responses to hypoxia, decreased HRV, and increased low-frequency SBPV. Remarkably, PAG treatment reduced the apnea index by 90%, reduced breath interval variability by 40–60%, and reversed the enhanced hypoxic CB afferent and chemoreflex responses observed in CHF rats. Furthermore, PAG treatment partially reversed the alterations in HRV and SBPV in CHF rats. Our results show that PAG treatment restores breathing stability and cardiac autonomic function and reduces the enhanced ventilatory and CB chemosensory responses to hypoxia in CHF rats. These results support the idea that PAG treatment could potentially represent a novel pathway to control sympathetic outflow and breathing instability in CHF.

Keywords: breathing, heart failure, hydrogen sulfide, chemoreflex, autonomic function.

chronic heart failure (CHF) is characterized by elevated sympathetic outflow and breathing instability, both considered major risk factors in the progression of CHF. Accordingly, it has been shown that cardiorespiratory disorders are closely related to a poor prognosis in patients with CHF (7, 12, 14, 17, 34, 38). Enhanced sensitivity of the peripheral chemoreflex has been proposed to mediate autonomic and respiratory dysfunction during CHF (6, 33, 37). Previous studies from our laboratory have demonstrated an augmented afferent input from the carotid body (CB) chemoreceptors in pacing-induced CHF rabbits and myocardial infarcted CHF rats (32). The mechanism underlying the increased CB chemosensory discharges following CHF has not been fully understood. Nevertheless, it has been shown that several chemosensory transmitters are involved in the CB potentiation observed in CHF animals (32, 33).

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is an important gaseous transmitter involved in several functions (15). While in the cardiovascular system H2S affects vascular relaxation (15, 40), in the nervous system H2S exerts its effects by modulation of synaptic transmission and neural excitability (2, 15). H2S synthesis has been attributed to three enzymes, cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase with CSE and CBS as the major sources for endogenous H2S levels (29). Recently, H2S has been proposed to partially contribute to the CB chemosensory function (22, 24, 27). Li et al. (19) showed that CSE and CBS enzymes are constitutively expressed in CB chemoreceptor cells. In addition, Peng et al. (27) found that hypoxic stimulation of the CB in vitro induces H2S formation in an oxygen-dependent manner and that transgenic mice deficient in the CSE complex display a poor CB chemosensory response to acute hypoxic stimulation. Accordingly, pharmacological inhibition of CSE using dl-propargylglycine (PAG) also impaired CB chemosensory responses to hypoxia in vitro (27). Thus supportive evidence indicates that the CB from animals in nonpathological conditions constitutively express both CSE and CBS enzymes and suggests that H2S derived from CSE contributes to the development of the CB chemosensory response to hypoxia.

In contrast to what is known about the effects of H2S on normal CB function, nothing is known about its role in disease conditions, including CHF. In the present study, we used PAG to determine the acute effects of inhibition of CSE-mediated H2S synthesis on breathing and autonomic abnormalities and enhanced CB chemoreflex function following myocardial infarction induced CHF in rats. We hypothesized that H2S inhibition reduces CB chemosensory discharges in the CHF state and improves breathing stability and cardiovascular autonomic function.

METHODS

Thirty-six male Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing between 360 and 430 g, were used in these experiments. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Nebraska Medical Center and were carried out under the guidelines of the American Physiological Society and the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Rat model of CHF.

CHF was produced by coronary artery ligation (CAL) as previously described (13). Briefly, rats were anesthetized (2% isoflurane-98%O2) and mechanically ventilated and then a left thoracotomy was performed. The left anterior descending coronary artery was ligated near its branch point from the aorta with a 6–0 silk suture. Following these maneuvers, the thorax was closed and the air within the thorax was evacuated. Sham-operated rats were prepared in the same manner but did not undergo CAL. All animals were allowed to resume spontaneous respiration and recover from anesthesia.

Rats were then housed in a temperature and humidity control environment with ad libitum access to food and water. All experiments were performed at 6 wk. after coronary artery ligation. Cardiac function and the degree of heart failure were determined by echocardiography (Vevo 770; Visualsonics). While animals were under isoflurane anesthesia, a two-dimensional, short-axis view of the left ventricle (LV) was obtained at the level of the papillary muscles. M-mode tracings were recorded through the anterior and posterior LV walls, and anterior and posterior wall thicknesses (end-diastolic and end-systolic) and LV internal dimensions were also measured. Rats with an ejection fraction as determined by echocardiogram of <45% were considered to be in CHF (13).

Radiotelemetric monitoring of arterial blood pressure and heart rate.

After 4 wk of sham or CAL surgery, rats were anesthetized (2% isoflurane) and a blood pressure (BP) radiotelemetry probe (Physiotel TA11PA-C40; Data Science International) was inserted into the left femoral artery and advanced to place the pressure-sensing catheter tip in the aorta. After 14 days of recovery, continuous changes in BP and heart rate (HR) were measured in the conscious freely moving state before and after PAG treatment.

Evaluation of HR variability and BP variability.

The total power of HR variability (HRV) and the low-frequency (LF) component of the systolic BP variability (SBPV) were used as indirect measures of autonomic balance as previously described (25). Briefly, BP recordings were obtained at 2 kHz over a 60-min period during the resting breathing test. HR was derived from the interpulse interval. HRV was analyzed using the HRV extension for LabChart 7 software (AD Instruments) over a 10-min recording characterized by the absence of movement-induced artifacts. Power spectral analysis was performed to calculate the total power of the HRV by integration of the whole spectrum. Changes in the LF of SBPV (LFSBPV) reflect the level of sympathetic vasoconstrictor activity. Accordingly, the power of the LFSBPV was calculated following FFT using 0.2–0.6 Hz as the cut-off frequency (36).

Evaluation of respiratory variability and ventilatory chemoreflex function.

Tidal volume (Vt), respiratory frequency (RR), and minute ventilation (V̇e: Vt × RR) were determined by unrestrained whole body plethysmography. Tidal volume was measured by temporarily (15–30 s) sealing the air ports and measuring the pressure changes in the sealed chamber using a Validyne (MP-45) differential pressure transducer and amplifier connected to a PowerLab System (AD Instruments). Chamber pressure fluctuations were proportional to tidal volume. Resting breathing was recorded for 2 h while the rats breathed room air. Peripheral chemoreceptors were stimulated preferentially by allowing the rats to breathe hypoxic (10% O2/balance N2) gas for 2–5 min under isocapnic conditions. Because hypoxic stimulation of ventilation induces hyperventilatory hypocapnia, 2–3% CO2 was added to the hypoxic mixture to maintain relatively constant PaCO2 during hyperventilation as previously described (37). Hyperoxic hypercapnia (7% CO2-93% O2) and normoxic hypercapnia (7% CO2) gas challenges were given for 2–5 min. All recordings were made at an ambient temperature of 25 ± 2°C. Respiratory stability was calculated during resting breathing recordings by Poincare plots and analysis of SD1 and SD2 of interbreath intervals variability (26) over 500 consecutive breaths. Apnea episodes (cessation of breathing ≥3 breaths), hypopneas (reductions ≥50% in Vt), and sigh frequency (single breath ≥50% increase in Vt) were averaged during resting breathing. During chemoreflex testing, respiratory variables (RR and Vt) were averaged for at least 20 consecutive breaths over a period of 4 min of inspired hypoxic and hypercapnic challenges.

Oxygen consumption measurements.

O2 uptake (V̇o2) and CO2 production (V̇co2) were measured by using the open-circuit method from the plethsysmograph during normoxia (FiO2 ∼21%) and hypoxia (FiO2 ∼10%). The chamber was airtight except for the in- and outflow ports at opposing ends of the chamber. O2 and CO2 analyzers (AD Instruments) monitored the inflowing and outflowing gas concentrations delivered through the chamber at a constant flow rate (1,000 ml/min) maintained by a calibrated flow meter. The outputs of the O2 and CO2 meters were acquired (PowerLab) and displayed on a computer to calculate V̇o2, V̇co2, and respiratory exchange ratio (RER). V̇o2 and V̇co2 (expressed in ml STPD·min−1·kg−1) were calculated from the average inflow-outflow difference in gas concentration over a time interval, multiplied by the flow.

Recording of CB chemosensory discharge.

CB afferent activity was recorded as previously described (8, 9). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with urethane (0.75 g/kg ip) and α-chloralose (70 mg/kg ip) and were placed in the supine position and the body temperature was maintained at 38.0 ± 0.5°C with a heating pad. Additional doses where used when necessary to maintain a level of surgical anesthesia. The trachea was cannulated, and the rat was mechanically ventilated (Kent Scientific). One carotid sinus nerve was dissected and placed on a pair of platinum electrodes and covered with warm mineral oil. The neural signal was preamplified (Grass P511), filtered (30 Hz-1 kHz), and fed to an electronic spike-amplitude discriminator, allowing the selection of action potentials of given amplitude above the noise to be counted with a frequency meter to measure the frequency of CB chemosensory discharge (ƒcsn), expressed in hertz (LabChart; AD Instruments). Carotid sinus barosensory fibers were eliminated by crushing the common carotid artery wall between the carotid sinus and the CB. The contralateral carotid sinus nerve was cut to prevent vascular and ventilatory reflexes evoked by the activation of the CB. Transection of the aortic depressor nerves was not necessary since aortic chemoreceptors have little contribution to the cardiorespiratory chemoreflex response to hypoxia in rats (31). The chemosensory discharge was measured at several FiO2 (10–100%).

Acute treatment with PAG.

Both sham and CHF rats first received a vehicle injection (1.2 ml NaCl 0.9% ip), and ventilatory and cardiovascular measurements were taken. Then, selective irreversible inhibition of the H2S-synthesizing enzyme CSE was addressed by PAG. For ventilatory and cardiovascular experiments, conscious rats were treated with a single ip injection of PAG (100 mg/kg). Drug dose was chosen based on previously reports showing that 100 mg/kg PAG effectively inhibit CSE activity in several tissues without affecting the activity of other H2S-synthesizing enzymes (16). Breathing (Vt and RR) was monitored over the subsequent 60 min after PAG. For CB chemosensory studies, carotid sinus nerve activity was recorded before and after 60 min of PAG injection (100 mg/kg ip). The drug was solubilized in sterile saline solution and prepared fresh on the day of use. To account for a possible role of higher BP on the cardiorespiratory changes observed in CHF rats after PAG treatment, we performed phenylephrine (PE) injections (3 mg/kg ip) to increase BP in CHF rats. Ventilatory chemoreflex, breathing pattern variability, and cardiovascular function were analyzed the same way as during the PAG treatment.

CSE expression in the CB.

At the end of the physiological studies, the CBs were quickly removed, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C. Proteins from 6–8 CBs were extracted with RIPA lysing buffer containing 1% complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Samples were pooled and run in triplicate after determination of protein concentration (BCA protein assay kit; ThermoScientific). An equal amount of protein was loaded into 10% polyacrylamide gel for electrophoretic separation. Gels containing the proteins were then transferred to PVDF membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore) at 4°C. The membranes were first incubated with blocking buffer (Odyssey Blocking Buffer; Li-Cor) and then incubated overnight at 4°C with a rabbit polyclonal anti-CSE antibody (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) followed by a 1-h incubation with a goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:10,000, IRDye 800CW; Li-Cor). Membranes were then developed using the Odyssey infrared fluorescence imaging systems (Li-Cor). Following stripping of the membranes (NewBlot; Li-Cor), protein loading was evaluated by probing all membranes with a mouse anti-β-actin antibody (1:2,500; Sigma). Analyses of the specific bands optical densities were performed using the Odyssey Infrared Fluorescence Imaging Software (Li-Cor). All data were normalized using CSE protein intensities to those of β-actin. No difference in the level of expression of β-actin was found between groups.

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± SE. Differences among three or more groups were assessed with one- or two-way ANOVA tests, followed by Newman- Keuls or Bonferroni post hoc comparisons. The Student's t-test was employed to compare the differences between two groups as well as comparing the effects of PAG on chemoreflex function. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Echocardiographic characteristics of sham and CHF rats.

Echocardiographic parameters were measured in sham and CHF rats (Table 1). Six weeks after coronary artery ligation, CHF rats exhibited a lower ejection fraction and fractional shortening compared with sham rats (P < 0.05). No statistical differences were found when comparing body weights (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Body and heart weight and echocardiographic variables in sham and CHF rats

| Sham | CHF | |

|---|---|---|

| BW, g | 424 ± 11 | 436 ± 8 |

| HW, mg | 1,433 ± 88 | 2,250 ± 75* |

| HW/BW, mg/g | 3.35 ± 0.12 | 5.15 ± 0.08* |

| LVESV, μl | 86.0 ± 9.4 | 358.5 ± 24.3* |

| LVEDV, μl | 262.6 ± 30.3 | 579.5 ± 27.9* |

| EF, % | 67.2 ± 0.8 | 36.8 ± 1.2* |

| FS, % | 38.4 ± 0.6 | 19.7 ± 0.9* |

Values are means ± SE. CHF, chronic heart failure; BW, body weight; HW, heart weight; LVESV, left ventricle end-systolic volume; LVEDV, left ventricle end-diastolic volume; EF, ejection fraction; FS, fractional shortening.

P < 0.05, compared with no sham.

Effects of PAG on the chemoreflex ventilatory response to hypoxia and hypercapnia.

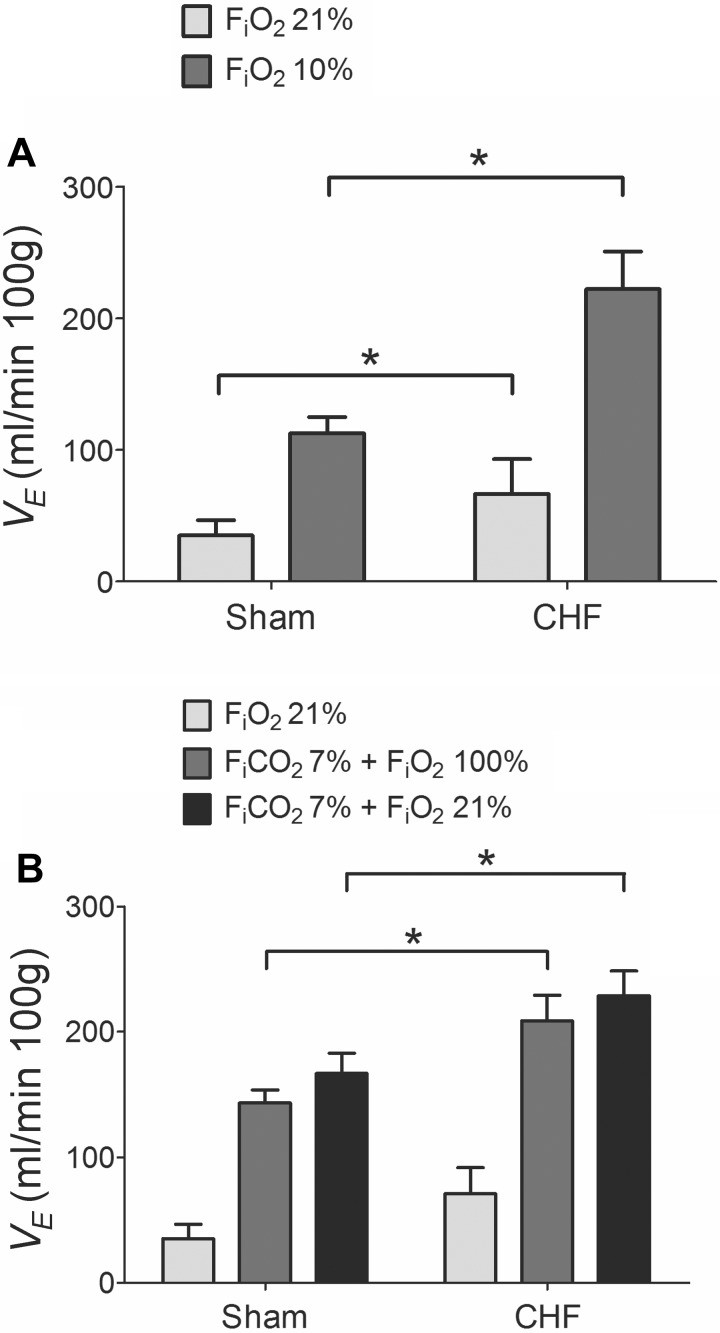

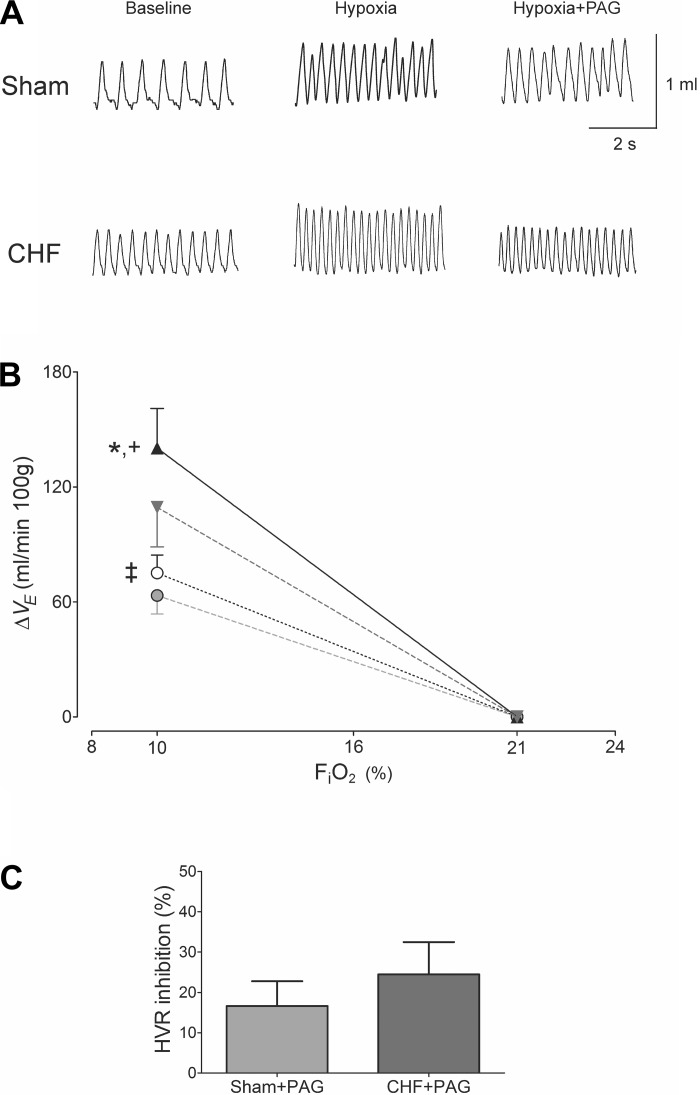

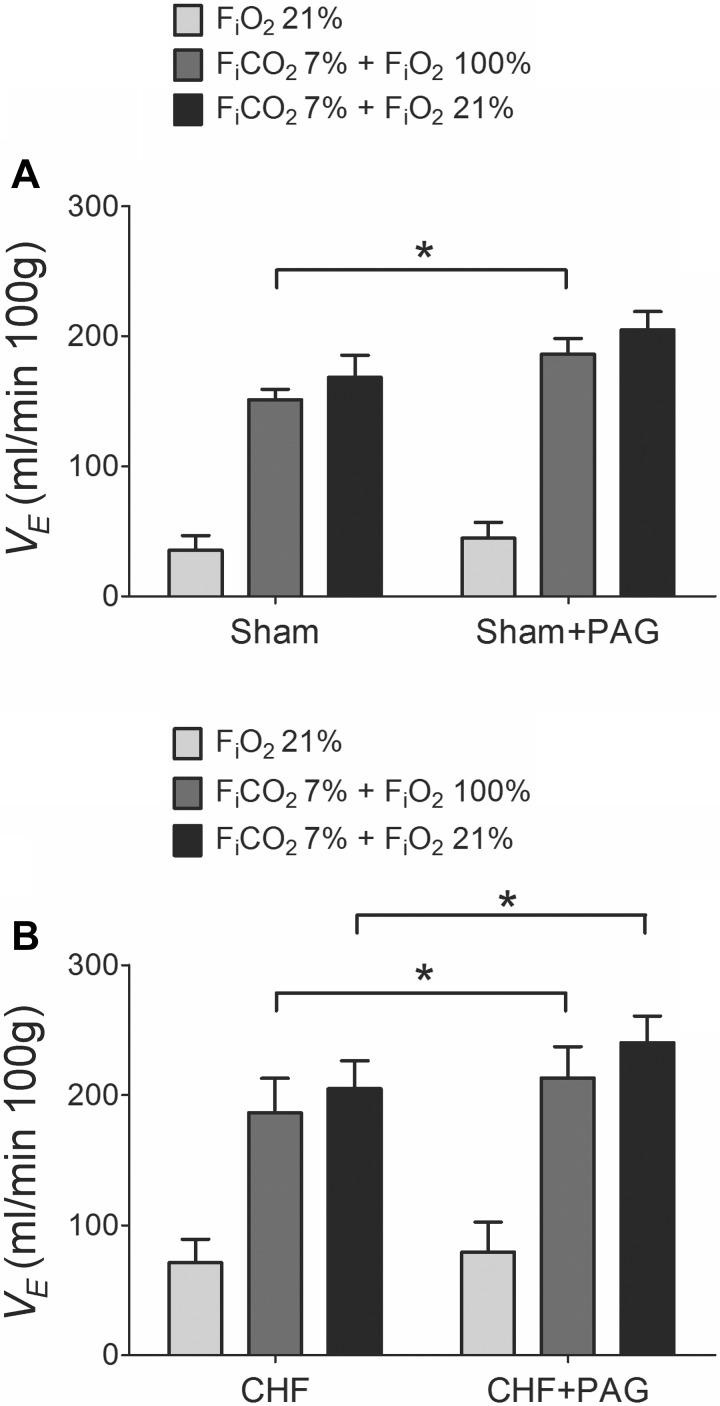

CHF rats developed an enhanced resting V̇e compared with sham group (70.89 ± 6.51 vs. 35.13 ± 4.04 ml·min−1·100 g−1, respectively), measured 6 wk after CAL. As shown in Fig. 1A, CHF rats also displayed a greater chemoreflex ventilatory response to 10% FiO2 (222.10 ± 28.67 ml·min−1·100 g−1) compared with sham rats (112.69 ± 12.23 ml·min−1·100 g−1). In addition, hypercapnic (7% FiCO2) ventilatory responses were potentiated in the CHF group compared with sham rats (Fig. 1B). After 1 h of PAG treatment, baseline V̇e was not altered in either group (P > 0.05, not shown). However, PAG treatment significantly reduced the hypoxic ventilatory response (FiO2 ∼10%) by about 15–25% in both CHF and sham rats (Fig. 2). In contrast, acute PAG treatment potentiated the ventilatory responses to hypercapnia. Indeed, sham rats displayed an increased hyperoxic-hypercapnic ventilatory response after 1 h of PAG (Fig. 3A). Similarly, CHF rats showed a significant 15% increase in the ventilatory response to hyperoxic-hypercapnia and a 17% increase in response to normoxic hypercapnia following PAG treatment (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 1.

Chronic heart failure (CHF) induced hypoxic and hypercapnic ventilatory potentiation in rats. A: ventilatory responses to 10% O2 in awake CHF and sham rats. Note that 6 wk after coronary artery ligation, rats developed increased resting ventilation (21% O2) as well as enhanced acute ventilatory responses to 10% O2 compared with the sham-operated group. Minute ventilation (V̇e). B: hypercapnic ventilatory responses in CHF and sham rats. Heart failure rats exhibited enhanced 7% CO2 ventilatory responses (balanced with 100% O2 as well as with 21% O2). *P < 0.05; n = 8 rats per group.

Fig. 2.

H2S inhibition by dl-propargylglycine (PAG) similarly reduced the hypoxic ventilatory response in sham-operated and CHF rats. A: representative tracings displaying Vt response to a hypoxic insult (FiO2 ∼ 10%) before and after PAG treatment in one sham and one CHF rat. B: PAG effects on the ventilatory response to acute hypoxia (FiO2 ∼10%) in CHF and sham rats expressed as the difference from the baseline values. ▲, CHF (n = 8); ▼, CHF + PAG (n = 8); ○, sham (n = 8); ●, sham + PAG (n = 8). *P < 0.05 CHF vs. sham; +P < 0.05 CHF vs. CHF + PAG; ‡P < 0.05 sham vs. sham + PAG. C: no difference was found in the percent inhibition of the hypoxic ventilatory responses (HVR = 10% FiO2) induced by PAG between sham and CHF rats. P > 0.05; n = 8 rats per group.

Fig. 3.

PAG treatment enhanced the ventilatory responses to hypercapnia in CHF and sham-operated rats. A: effect of PAG treatment on the ventilatory responses to 7% FiCO2 in sham rats. PAG potentiated the hyperoxic-hypercapnic (7% FiCO2 balanced with 100% O2) response in sham rats without affecting the ventilatory response to normoxic-hypercapnia (7% FiCO2 balanced with 21% O2). B: effect of PAG treatment on the ventilatory responses to hypercapnia in CHF rats. Note that PAG treatment significantly increased both hypercapnic responses in CHF rats. *P < 0.05; n = 8 rats per group.

Effects of PAG on oxygen uptake during normoxia and in response to hypoxia.

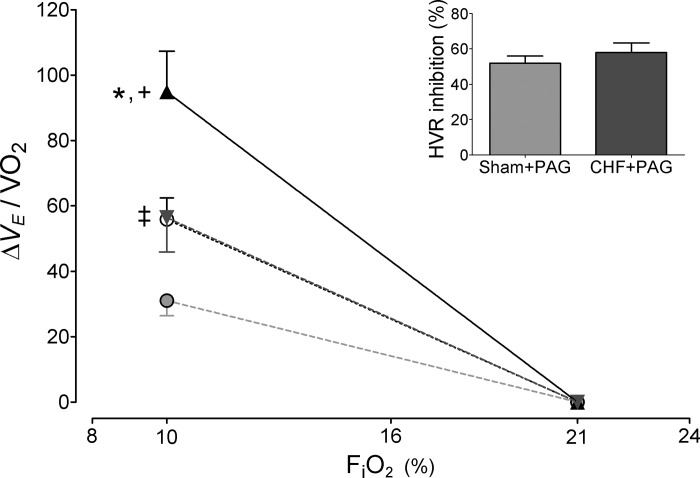

Infarcted-rats displayed no difference in V̇o2, V̇co2, and RER during normoxia compared with values obtained in sham rats (P > 0.05; Table 2). Hypoxic stimulation (FiO2 ∼10%) induced comparable decreases in V̇o2 in both sham and CHF rats (from 19.6 ± 1.1 to 14.1 ± 1.1 ml · min−1 · kg−1 and from 20.8 ± 1.2 to 16.4 ± 0.9 ml · min−1 · kg−1, sham and CHF, respectively). Correction of the reflex hypoxic ventilatory responses for V̇o2 (Fig. 4) did not modify the enhancement of the reflex seen in CHF rats compared with sham.

Table 2.

Effects of PAG on normoxic and hypoxic O2 consumption and CO2 production in sham and CHF rats

| Sham | Sham + PAG | CHF | CHF + PAG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normoxia | ||||

| V̇o2 | 19.6 ± 1.1 | 21.9 ± 0.9 | 20.8 ± 1.2 | 19.9 ± 1.4 |

| V̇co2 | 13.9 ± 1.2 | 16.0 ± 0.7 | 15.3 ± 1.0 | 14.6 ± 0.8 |

| RER | 0.71 ± 0.03 | 0.73 ± 0.02 | 0.73 ± 0.01 | 0.74 ± 0.02 |

| Hypoxia | ||||

| V̇o2 | 14.1 ± 1.1* | 21.0 ± 1.3 | 16.4 ± 0.8† | 19.6 ± 0.5 |

| V̇co2 | 13.5 ± 1.4 | 16.3 ± 0.6 | 16.3 ± 2.1 | 16.1 ± 0.6 |

| RER | 0.91 ± 0.05* | 0.77 ± 0.05 | 0.96 ± 0.04† | 0.82 ± 0.03 |

Values are means ± SE. Normoxia, FiO2 ∼21%; hypoxia, FiO2 ∼10%; V̇o2, oxygen uptake in ml·min−1·kg−1; V̇co2, CO2 production in ml·min−1·kg−1; RER, respiratory exchange ratio. Sham, n = 4; sham + dl-propargylglycine (PAG), n = 4; CHF, n = 4; CHF + PAG, n = 4.

P < 0.05, compared with sham normoxic value;

P < 0.05, compared with CHF normoxic value (Newman-Keuls after one-way ANOVA).

Fig. 4.

Effects of PAG on the hypoxic ventilatory response normalized for V̇o2. Summary of the data showing the response to acute hypoxia (FiO2 ∼10%) in CHF and sham rats expressed as the difference from the baseline values and corrected by V̇o2. ▲, CHF; ▼, CHF + PAG; ○, sham; ●, sham + PAG. *P < 0.05 CHF vs. sham; +P < 0.05 CHF vs. CHF + PAG; ‡P < 0.05 sham vs. sham + PAG. Inset: percent inhibition of the HVR (=10% FiO2) induced by PAG between sham and CHF rats. P > 0.05; n = 8 rats per group.

Following 1 h of PAG treatment, no changes in resting normoxic V̇o2, V̇co2, and RER were found in both CHF and sham groups (Table 2). However, PAG treatment significantly reduced the depression in oxygen consumption during hypoxic stimulation. Indeed, after PAG both sham and CHF V̇o2 values during the hypoxic test were similar to the ones obtained at normoxia (Table 2). In contrast, no significant changes were found in the hypoxic V̇co2 response after PAG treatment. The reflex hypoxic ventilatory response corrected by V̇o2 continued to demonstrate a significant reduction after PAG treatment in both sham and CHF rats (Fig. 4).

Effects of PAG on breathing variability and apnea index in CHF rats.

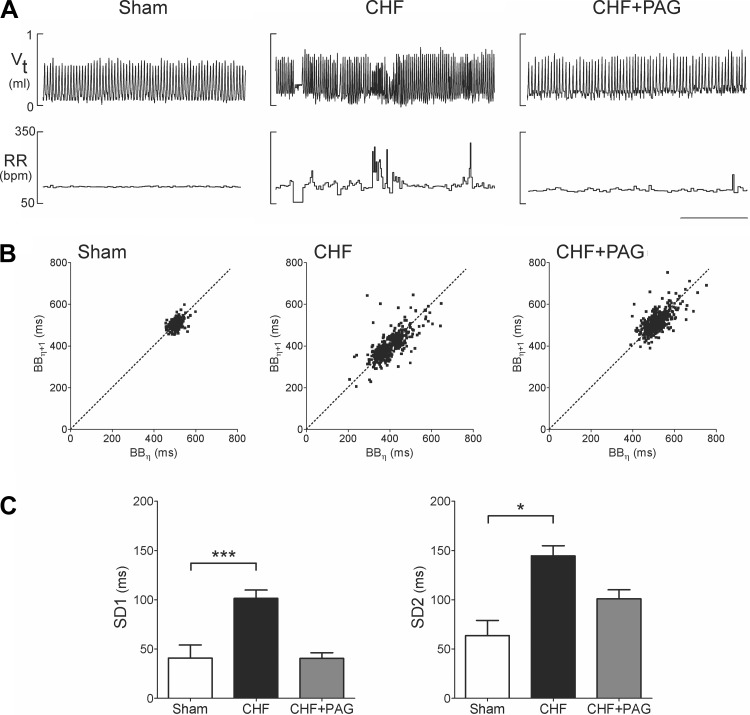

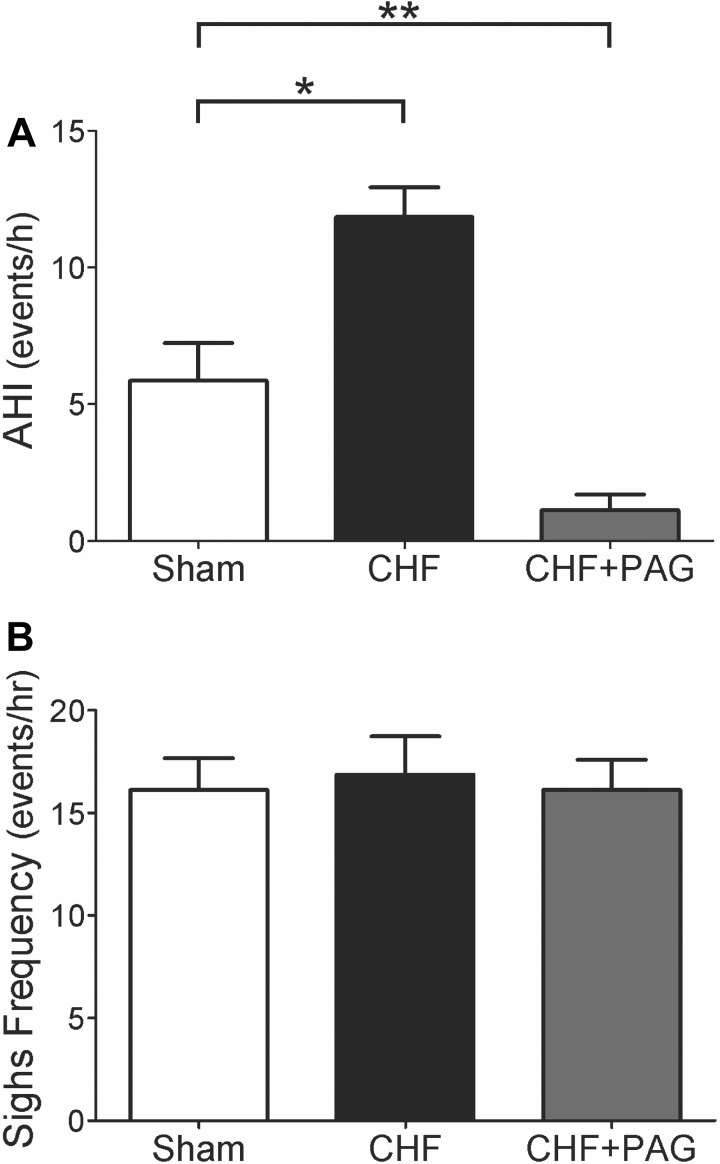

Rats with infarct-induced CHF exhibited an irregular breathing pattern with brief periods of hyperventilation followed by hypoventilation while resting at FiO2 21%, whereas sham rats exhibited a regular breathing pattern (Fig. 5A). Analysis of breath-to-breath (BB) interval (BBn) vs. the subsequent interval (BBn + 1) showed a greater interbreath variability of BB in CHF compared with sham rats. Figure 5, B and C (Poincare plots), illustrates the analysis of the SD of BB intervals and shows that SD1 (representing the y-axis) and SD2 (representing the x-axis) were significantly greater in CHF compared with sham rats (SD1, 101.4 ± 8.5 ms vs. 40.9 ± 13.2 ms, P < 0.05; SD2, 100.9 ± 9.1 ms vs. 63.7 ± 15.4 ms, P < 0.05, CHF vs. sham). Inhibition of H2S synthesis with PAG reverted breathing interval variability in CHF rats toward that seen in sham rats (Fig. 5). Remarkably, we found that PAG treatment induced a significant 60% reduction in SD1 and a 30% reduction in SD2 in the CHF group (P < 0.05; Fig. 5C). In contrast, no effects of PAG were found on either SD1 or SD2 in sham rats (not shown). In addition, we found that CHF rats exhibited a greater number of apnea episodes compared with sham rats (Fig. 6). The incidence of apneas in the CHF group was twofold higher compared with sham rats. As depicted in Fig. 6A, PAG treatment significantly reduced the apnea/hypoapnea index (AHI) in CHF rats (Fig. 6A) to a level less than that observed even in sham rats. We also found that PAG induced a decrease in the number of apnea episodes in sham rats from 5.8 ± 1.4 episodes to 1.8 ± 0.6 episodes per hour (P < 0.05). No differences in the number of spontaneous sighs were found between groups (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

H2S synthesis inhibition by PAG treatment restored breathing stability in CHF rats. A: representative tracings displaying tidal volume (Vt) and respiratory frequency (RR) in one sham-operated rat, and one CHF rat before and after PAG. Breathing instability was evident in rats with myocardial infarction-induced CHF. Note the presence of spontaneous cessation of breathing and changes in Vt and RR at rest. B: representative Poincare plots showing the breath-to-breath interval variability in the same rats illustrated in A. Cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) inhibition by PAG improved breathing stability in CHF. C: summary of the data showing the effects of PAG on SD1 (short-term variability) and SD2 (long-term variability) in breathing interval. Both SD1 and SD2 were increased in CHF rats. PAG treatment significantly reduced both indices in rats with CHF. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; n = 8 rats per group.

Fig. 6.

Effects of CSE inhibition with PAG on the incidence of apneas and hypopneas in rats with CHF. A: rats with CHF exhibited an increased apnea/hypoapnea index (AHI) compared with sham-operated rats. PAG treatment suppressed the augmented incidence of apneas in CHF rats below levels seen even in sham animals. B: effect of PAG on the frequency of spontaneous sighs. No significant effects of PAG were found in the number of sighs. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; n = 8 rats per group.

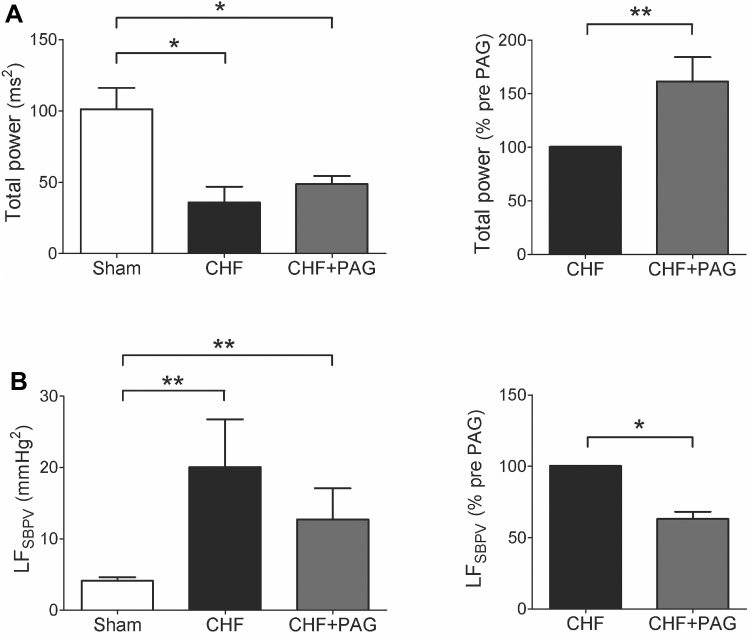

Effects of PAG on HRV and SBPV.

H2S has been recognized to exert vascular relaxation. We monitored changes in BP and HR before and after PAG treatment in both sham and CHF rats. As shown in Table 3, PAG treatment tended to increase BP and HR in both sham and CHF groups. Nevertheless, no significant differences were found in either systolic, diastolic and pulse pressure or HR in either group due to CSE inhibition with PAG 100 mg/kg (see Table 3). Rats with CHF exhibited a threefold reduction in the total power of the HRV compared with sham rats (Fig. 7A). In addition, CHF rats presented a significant increase in the sympathetic-mediated vasomotor tone compared with sham rats as reflected in the LFSBPV (20.1 ± 6.7 vs. 4.1 ± 0.5 mmHg2, CHF vs. sham, respectively). Acute inhibition of H2S formation with PAG increased HRV and reduced the LFSBPV in CHF rats (Fig. 7B). No statistically significant effects of PAG were found in both HRV and SBPV in sham rats. In fact, the total power of the HRV showed a 7% reduction while the LFSBPV increased by 8% after PAG treatment in sham rats.

Table 3.

Effects of PAG on baseline hemodynamics in sham and CHF rats

| Sham | Sham + PAG | CHF | CHF + PAG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP, mmHg | 101.5 ± 6.7 | 105.5 ± 15.5 | 102.3 ± 7.0 | 116.9 ± 6.2 |

| DBP, mmHg | 68.6 ± 3.4 | 67.5 ± 11.2 | 68.5 ± 3.7 | 80.1 ± 2.7 |

| PP, mmHg | 33.0 ± 3.7 | 38.0 ± 4.3 | 33.7 ± 3.4 | 36.8 ± 3.6 |

| MBP, mmHg | 82.9 ± 4.8 | 84.3 ± 13.2 | 83.3 ± 5.5 | 96.8 ± 4.5 |

| HR, beats/min | 305.3 ± 25.9 | 325.9 ± 27.7 | 296.0 ± 12.4 | 345.1 ± 24.5 |

Values are means ± SE. SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; PP, pulse pressure; MBP, mean blood pressure; HR, heart rate. Sham, n = 4; sham + PAG, n = 2; CHF, n = 4; CHF + PAG, n = 4. No statistical differences between pre- and post-PAG treatment were found among groups (P > 0.05, Newman-Keuls after one-way ANOVA).

Fig. 7.

Effects of PAG on HRV and systolic blood pressure variability (SBPV) in CHF rats. A: rats with CHF displayed a marked decrease in HRV total power compared with sham rats (A, left). PAG treatment improved HRV in CHF rats (A, right). Note that PAG did not restore the HRV values of CHF rats back to normal levels. B: effect of PAG treatment on the low-frequency (LF) SBPV. Rats with CHF showed a significant increase in the LF domain compared with sham rats. PAG decrease the LFSBPV in CHF rats. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Sham, n = 4; sham + PAG, n = 2; CHF, n = 4; CHF + PAG, n = 4.

Effects of BP on chemoreflex function, respiratory variability, HRV, and SBPV in CHF rats.

Although PAG did not induce a significant increase in BP in either sham or CHF rats, a small change in BP may have influenced in part the cardiorespiratory effects of PAG in CHF rats. In a subset of experiments, we injected CHF rats with a single dose of PE (3 mg/kg ip) to induce a similar increase in BP (Δmean arterial pressure: 15.4 ± 3.7 mmHg). We found that the PE-induced increase in BP was not associated with ventilatory chemoreflex potentiation or inhibition and had null effects on breathing variability observed in CHF rats (Table 4). Also, we found no significant changes in HRV and LFSBPV during PE compared with vehicle in CHF rats (Table 4).

Table 4.

Cardiorespiratory responses to phenylephrine in CHF rats

| CHF + Vehicle | CHF + PE | |

|---|---|---|

| Ventilatory chemoreflex | ||

| V̇e (FiO2 10%), ml·min−1·100 g−1 | 100.6 ± 9.9 | 91.1 ± 13.1 |

| V̇e (FiCO2 7%), ml·min−1·100 g−1 | 135.4 ± 5.4 | 159.7 ± 30.5 |

| Respiratory variability | ||

| SD1, ms | 132.0 ± 12.9 | 104.6 ± 4.5 |

| SD2, ms | 147.0 ± 10.1 | 126.2 ± 8.7 |

| AHI, events/h | 14.8 ± 1.7 | 10.5 ± 1.6 |

| Heart rate variability | ||

| HRV total power, %pre-PE | 100.0 ± 28.9 | 71.5 ± 12.5 |

| Blood pressure variability | ||

| LFSBPV, %pre-PE | 100.0 ± 7.3 | 142.9 ± 27.2 |

Values are means ± SE. PE, phenylephrine (3 mg/kg ip); V̇e, minute ventilation; SD1 and 2, standard deviation 1 and 2; AHI, apnea/hypoapnea index; HRV, heart rate variability; SBPV, systolic blood pressure variability; LFSBPV, low-frequency of SBPV. No statistical differences were found (P > 0.05, compared to CHF + vehicle); n = 4, each group.

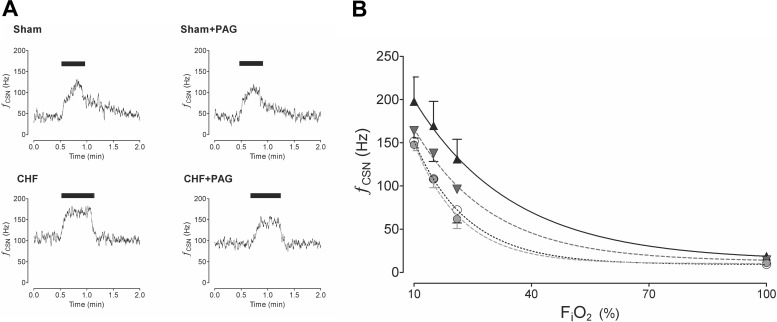

Effects of PAG on CB afferent hypoxic and hypercapnic chemosensitivity.

Figure 8A shows representative tracings of the CB chemosensory response to acute hypoxia. Rats with CHF exhibited exaggerated CB chemoreceptor responses to hypoxia compared with sham rats. Moreover, baseline CB activity in normoxia was also augmented in CHF rats (Fig. 8A). We found that PAG treatment reduced the CB response to hypoxia in both sham and CHF rats (Fig. 8B). Nevertheless, it is important to note that a significant CB responsiveness to low oxygen levels remained after PAG treatment in both groups (Fig. 8). The two-way ANOVA analysis showed that the overall CB chemosensory curve for FiO2 was different between the CHF and CHF + PAG rats (P < 0.05). In addition, the CB chemosensory response to hypoxia (FiO2 10%) was not different between CHF + PAG and sham + vehicle rats (157.2 ± 7.1 vs. 141.8 ± 9.5 Hz, CHF + PAG vs. sham + vehicle rats, respectively). Also, PAG treatment reduced baseline CB chemosensory discharges in CHF rats but not in the sham-treated rats (Fig. 8). Thus PAG restored normal CB function in response to hypoxia in CHF animals. PAG treatment did not affect the CB afferent response to hypercapnia. CB activity in response to 7% CO2 was 213.4 ± 33.2 Hz before PAG treatment vs. 209.3 ± 36.3 Hz after PAG treatment in CHF rats.

Fig. 8.

PAG treatment reduced carotid body (CB) chemoreceptor activity in CHF rats in response to hypoxia. A: representative recordings from the CB from a sham rat and the CB from a CHF rat showing the chemosensory response to acute hypoxia (FiO2 ∼10%, bar) before and after PAG treatment. B: summary data of the effect of PAG on the CB chemosensory function in CHF. PAG significantly reduced the overall CB chemosensory discharge curve in response to several O2 levels in both CHF and sham rats (P < 0.05, two-way ANOVA). ▲, CHF (n = 4); ▼, CHF + PAG (n = 4); ○, sham (n = 4); ●, sham + PAG (n = 4).

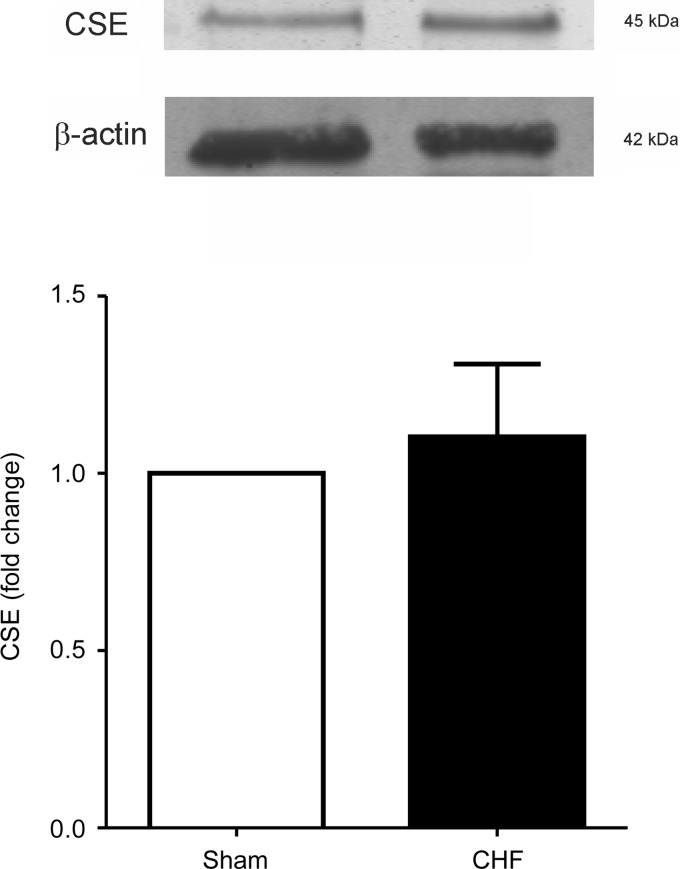

Expression of CSE in the CB.

The expression of CSE was addressed by immunoblot in the CBs from sham and CHF rats. In agreement with previous reports (19, 27), we found that CSE is constitutively expressed in the CBs from sham control rats (Fig. 9). In addition, we found that CBs from CHF rats displayed normal CSE expression compared with those obtained from sham CBs (P > 0.05).

Fig. 9.

Rats with CHF displayed normal CSE expression levels in the CB. Top: representative immunoblots showing no difference in the CSE expression levels in the CBs from CHF rats compared to those from sham rats. Bottom: summary data from 6 CBs from sham rats and 8 CBs from CHF rats run in triplicate. No significant difference was found between the 2 conditions.

DISCUSSION

In the present study we show that rats that develop CHF by myocardial infarction display potentiation of the CB chemoreflex associated with autonomic and respiratory imbalance. The main findings of the present study show that inhibition of CSE-mediated H2S synthesis by PAG: 1) normalizes the potentiated CB chemoreflex, 2) reverts breathing instability and virtually eliminates AHI, and 3) improves autonomic function to the heart and vasculature in CHF rats.

It has been shown that CB-mediated chemoreflex function is enhanced during the development of CHF and that this change plays a critical role in the activation of the sympathetic nervous system (37). Indeed, CHF patients exhibit increased chemosensitivity compared with healthy subjects (6). In addition, CHF patients also display breathing disorders characterized by periodic respiration and increased AHI compared with normal subjects (6, 7, 34, 39). Furthermore, breathing abnormalities have been associated with high mortality risk in CHF patients (14, 15). Solin et al. (35) showed that peripheral chemosensitivity is strongly related to the incidence of apneas in CHF, suggesting that the CB is a key factor in mediating the unstable breathing patterns. In addition, it has been shown that genetic manipulation towards a hyperreactive CB chemoreflex phenotype leads to breathing pattern irregularities and autonomic imbalance in mice (26). Thus it is plausible that the enhanced CB afferent input to the brainstem during CHF impacts the respiratory control loop gain (11). From this model, enhancement of CB chemoreceptor function (i.e., loop gain controller) would induce a progressive breathing instability (11, 23). In the present study we show that rats with CHF, which present an enhanced CB chemoreflex drive, display increase BB interval variability and a twofold increase in the incidence of apneas compared with sham-operated rats. Remarkably, we found that PAG treatment decreases the CB-mediated hypoxic ventilatory response (Fig. 1) and also significantly reduces the breathing instability and the number of apnea episodes in CHF rats to values similar to those obtained in sham rats.

It has been proposed that one of the mechanisms that contribute to the development of apneas during CHF is the change in the apnea threshold. We show that CHF rats exhibit an increased hypercapnic ventilatory response after PAG treatment. Thus it is likely that PAG treatment, by reducing CB afferent activity and increasing central CO2 sensitivity, raises the apnea threshold in CHF rats to stabilize breathing. Accordingly, Lorenzi-Filho et at. (21) showed that increasing the central CO2 sensitivity by inhalation of CO2 normalized the occurrence of apnea episodes in patients with CHF.

The changes in CB afferent activity and central CO2 sensitivity evoked by PAG are counter to what may be predicted in other models of peripheral-central chemoreflex interaction. Blain et al. (4) showed in an elegant experiment that CB afferent activity controls the central chemoreceptor sensitivity to hypercapnia in a hyperadditive manner. Thus one might expect that the ability of PAG to reduce CB afferent input should result in a dampening of central CO2 sensitivity. Apparently other factors come into play in our present study to account for the ability of PAG to increase the hypercapnic ventilatory response. Our finding that PAG did not affect the CB afferent response to CO2 indicates that this effect lies outside of the CB, most likely at the level of central chemoreceptor function. Because CSE is expressed in brain blood vessels (18), it is plausible that the PAG effects on enhancing the hypercapnic ventilatory response could be related to changes in cerebral blood flow. In addition, it has been shown that PAG can reduce H2S availability in the cerebrospinal fluid (18) then limiting H2S in chemosensitive areas. Thus it is conceivable that PAG may directly influence central chemoreceptor excitability to enhance CO2 sensitivity and increase the hypercapnic ventilatory response. It is important to note that the present study represents the first evidence showing that PAG increases CO2 sensitivity, but further research is needed to understand the H2S contribution on the regulation of cerebral blood flow and central chemoreceptor CO2 sensitivity.

One of the other important adverse influences during CHF is excessive sympathetic outflow. In the present study, CHF rats displayed autonomic imbalance characterized by a decreased HRV accompanied by an increase in LFSBPV, changes consistent with increased sympathetic outflow. It is well established that activation of the CB chemoreflex enhances sympathetic drive (8, 10, 20, 37). In the present study we provide evidence that inhibition of CSE reduced the CB afferent responsiveness to hypoxia (Fig. 8) and increased HRV and reduced the LF of SBPV in CHF animals. While these results suggest a relationship between CB afferent input and autonomic tone, CSE expression is not restricted only to the CB. We cannot exclude a direct effect of PAG in brain cardiovascular control centers or in other regions involved with autonomic function. It has been proposed that H2S can modulate synaptic plasticity in the central nervous system (1). Indeed, H2S increases excitatory postsynaptic currents and facilitates synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Then, a reduction in H2S following PAG treatment in the vicinity of the cardiovascular control areas within the brain could decrease presympathetic neurons firing rate and finally reduce the sympathetic outflow. Future studies are needed to unveil the mechanism involved in the PAG effects on the autonomic function during CHF, but the present results indicate that CSE inhibition abates CB hyperresponsiveness in CHF as a major contributing mechanism.

It has been shown that inhibition of H2S using PAG results in vasoconstriction and increases in systemic BP. Moreover, homozygous mutant mice lacking CSE enzyme display an age-dependent rise in BP (40). We found that PAG treatment tended to slightly increase resting BP in both sham and CHF rats. Similar increases in BP evoked by PE had no effects on hypoxic ventilatory responses, breathing variability, HRV, or SBPV in CHF rats. Together, the hypertensive effect of PAG cannot account for its cardiorespiratory effects during CHF.

The present results showing that CSE expression is maintained in the CB during CHF and that CSE inhibition reduced CB afferent responsiveness suggest that H2S contributes to the maintenance of exaggerated CB afferent responsiveness in CHF. H2S causes a rapid reversible increase in intracellular calcium in CB type 1 cells (5). It has been shown that H2S excites type 1 cells through the inhibition of background (TASK) potassium channels in rats (5) and big conductance Ca2+-sensitive K+ (BKCa) currents in mice (19). Recent studies (28) suggest that H2S function in the CB may be linked to HO-2 due to an inhibitory influence of CO on CSE enzyme activity. This concept is supported by our present and prior studies (10). We have shown previously that HO-2 is downregulated in the CB in CHF (10), which would promote CSE activity and H2S-mediated modulation of CB chemoreceptor afferent activity as observed in the CHF rats under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions. However, other mechanisms also play a prominent role in altered CB function in CHF (10, 20), which may explain why PAG did not completely restore the CB afferent responsiveness in CHF rats to the normal state (i.e., sham rats). Further, it is important to note that both CSE and CBS have been shown to be constitutively expressed in the CB (19). Thus although CSE appears to be a major source for H2S synthesis in the rat CB, we cannot rule out that CHF could induce increased CBS expression in the CB. In this regard, H2S inhibition of BKCa channels in type I cells of mice was sensitive to CBS inhibitors but not CSE inhibitors (19). Therefore, future studies are needed to address the contribution of other H2S-synthesizing enzymes on the CB function following CHF.

It is important to note that we found that PAG reverses the decrease in oxygen uptake during hypoxic stimulation in both sham and CHF rats. It is well known that the rodent response to acute hypoxic stimulation is characterized by an acute change in metabolic rate. Indeed, a hypometabolic response to hypoxia has been previously shown in rats (30). Thus the decreases in V̇o2 during hypoxic stimulation in CHF rats confirm previous results obtained in normal healthy rats and add new information regarding the hypoxic metabolic response in rats with low-output heart failure. Surprisingly, we found that inhibition of H2S production by PAG abates the hypoxic hypometabolic response in control and infarcted rats. This result suggests a plausible role for H2S in the metabolic response to acute hypoxia. Blackstone et al. (3) proposed that H2S could induce a “suspended animation-like state” characterized by a significant reduction in basal metabolism. Thus we speculate that the hypoxic hypometabolic response observed in rats is mediated by H2S because it is abolished after CSE inhibition. Further studies using H2S donors are required to confirm this.

In summary, CHF rats present augmented resting breathing, enhanced hypoxic and hypercapnic ventilatory responses, breathing instability and increased apnea incidence, and autonomic dysfunction compared with sham rats. Associated with these changes, CHF rats exhibited potentiation of CB chemosensory function. In the present study we provide evidence showing that treatment with a H2S synthesis inhibitor reduces the hypoxic chemoreflex ventilatory response, decreases augmented CB afferent chemosensitivity, and improves breathing rhythmogenesis and autonomic balance in CHF rats. In addition, we proposed that H2S participates in the metabolic response to hypoxia. Taken together, PAG treatment could potentially represent a novel pathway to control sympathetic outflow and breathing instability associated with CHF.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Program Project Grant PO1-HL-62222 and by SOVA Pharmaceuticals.

DISCLOSURES

A portion of the study was funded by a corporate grant from SOVA Pharmaceuticals.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: R.D.R., N.J.M., and H.D.S. conception and design of research; R.D.R. performed experiments; R.D.R. analyzed data; R.D.R., N.J.M., and H.D.S. interpreted results of experiments; R.D.R. prepared figures; R.D.R. drafted manuscript; R.D.R., N.J.M., and H.D.S. edited and revised manuscript; R.D.R., N.J.M., and H.D.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Kurtis G. Cornish for surgical assistance and management of the heart failure animal core at University of Nebraska Medical Center, Mary Ann Zink, Francisca Allendes, Johnnie F. Hackley, and Richard Robinson for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abe K, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous neuromodulator. J Neurosci 16: 1066–1071, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Austgen JR, Hermann GE, Dantzler HA, Rogers RC, Kline DD. Hydrogen sulfide augments synaptic neurotransmission in the nucleus of the solitary tract. J Neurophysiol 106: 1822–1832, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blackstone E, Morrison M, Roth MB. H2S induces a suspended animation-like state in mice. Science 308: 518, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blain GM, Smith CA, Henderson KS, Dempsey JA. Peripheral chemoreceptors determine the respiratory sensitivity of central chemoreceptors to CO(2). J Physiol 588: 2455–2471, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buckler KJ. Effects of exogenous hydrogen sulphide on calcium signalling, background (TASK) K channel activity and mitochondrial function in chemoreceptor cells. Pflügers Arch 463: 743–754, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chugh SS, Chua TP, Coats AJ. Peripheral chemoreflex in chronic heart failure: friend and foe. Am Heart J 132: 900–904, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Corra U, Pistono M, Mezzani A, Braghiroli A, Giordano A, Lanfranchi P, Bosimini E, Gnemmi M, Giannuzzi P. Sleep and exertional periodic breathing in chronic heart failure: prognostic importance and interdependence. Circulation 113: 44–50, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Del Rio R, Moya EA, Iturriaga R. Carotid body and cardiorespiratory alterations in intermittent hypoxia: the oxidative link. Eur Respir J 36: 143–150, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Del Rio R, Muñoz C, Arias P, Court FA, Moya EA, Iturriaga R. Chronic intermittent hypoxia-induced vascular enlargement and VEGF upregulation in the rat carotid body is not prevented by antioxidant treatment. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 301: L702–L711, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ding Y, Li YL, Schultz HD. Downregulation of carbon monoxide as well as nitric oxide contributes to peripheral chemoreflex hypersensitivity in heart failure rabbits. J Appl Physiol 105: 14–23, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Edwards BA, Sands SA, Berger PJ. Postnatal maturation of breathing stability and loop gain: the role of carotid chemoreceptor development. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 185: 144–155, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Floras JS. Clinical aspects of sympathetic activation and parasympathetic withdrawal in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 22: 72A–84A, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haack KK, Engler CW, Papoutsi E, Pipinos II, Patel KP, Zucker IH. Parallel changes in neuronal AT1R and GRK5 expression following exercise training in heart failure. Hypertension 60: 354–361, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hanly PJ, Zuberi-Khokhar NS. Increased mortality associated with Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 153: 272–276, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kimura H, Nagai Y, Umemura K, Kimura Y. Physiological roles of hydrogen sulfide: synaptic modulation, neuroprotection, and smooth muscle relaxation. Antioxid Redox Signal 7: 795–803, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kodama H, Mikasa H, Sasaki K, Awata S, Nakayama K. Unusual metabolism of sulfur-containing amino acids in rats treated with DL-propargylglycine. Arch Biochem Biophys 225: 25–32, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lanfranchi PA, Braghiroli A, Bosimini E, Mazzuero G, Colombo R, Donner CF, Giannuzzi P. Prognostic value of nocturnal Cheyne-Stokes respiration in chronic heart failure. Circulation 99: 1435–1440, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leffler CW, Parfenova H, Basuroy S, Jaggar JH, Umstot ES, Fedinec AL. Hydrogen sulfide and cerebral microvascular tone in newborn pigs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H440–H447, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li Q, Sun B, Wang X, Jin Z, Zhou Y, Dong L, Jiang LH, Rong W. A crucial role for hydrogen sulfide in oxygen sensing via modulating large conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Antioxid Redox Signal 12: 1179–1189, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li YL, Xia XH, Zheng H, Gao L, Li YF, Liu D, Patel KP, Wang W, Schultz HD. Angiotensin II enhances carotid body chemoreflex control of sympathetic outflow in chronic heart failure rabbits. Cardiovasc Res 71: 129–138, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lorenzi-Filho G, Rankin F, Bies I, Douglas Bradley T. Effects of inhaled carbon dioxide and oxygen on Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 159: 1490–1498, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Makarenko VV, Nanduri J, Raghuraman G, Fox AP, Gadalla MM, Kumar GK, Snyder SH, Prabhakar NR. Endogenous H2S is required for hypoxic sensing by carotid body glomus cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 303: C916–C923, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Naughton MT. Loop gain in apnea: gaining control or controlling the gain? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 181:103–105, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Olson KR. Hydrogen sulfide is an oxygen sensor in the carotid body. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 179: 103–110, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pagani M, Lombardi F, Guzetti S, Rimoldi O, Furlan R, Pizzinelli P, Sandrone G, Malfatto G, Dell'Orto S, Piccaluga E, Turiel M, Baselli G, Cerutti S, Malliani A. Power spectral analysis of heart rate and arterial pressure variabilities as a marker of sympatho-vagal interaction in man and conscious dog. Circ Res 59: 178–193, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Peng YJ, Nanduri J, Khan SA, Yuan G, Wang N, Kinsman B, Vaddi DR, Kumar GK, Garcia JA, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Hypoxia-inducible factor 2α (HIF-2α) heterozygous-null mice exhibit exaggerated carotid body sensitivity to hypoxia, breathing instability, and hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 3065–3070, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Peng YJ, Nanduri J, Raghuraman G, Souvannakitti D, Gadalla MM, Kumar GK, Snyder SH, Prabhakar NR. H2S mediates O2 sensing in the carotid body. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 10719–10724, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Prabhakar NR. Carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) in hypoxic sensing by the carotid body. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 184: 165–169, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Renga B. Hydrogen sulfide generation in mammals: the molecular biology of cystathionine-beta-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine-gamma-lyase (CSE). Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 10: 85–91, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Saiki C, Matsuoka T, Mortola JP. Metabolic-ventilatory interaction in conscious rats: effect of hypoxia and ambient temperature. J Appl Physiol 76: 1594–1599, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sapru HN, Krieger AJ. Carotid and aortic chemoreceptor function in the rat. J Appl Physiol 42: 344–348, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schultz HD, Del Rio R, Ding Y, Marcus NJ. Role of neurotransmitter gases in the control of the carotid body in heart failure. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 184: 197–203, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schultz HD, Li YL, Ding Y. Arterial chemoreceptors and sympathetic nerve activity: implications for hypertension and heart failure. Hypertension 50: 6–13, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schulz R, Blau A, Börgel J, Duchna HW, Fietze I, Koper I, Prenzel R, Schädlich S, Schmitt J, Tasci S, Andreas S; Working Group Kreislauf und Schlaf of the German Sleep Society (DGSM). Sleep apnea in heart failure. Eur Respir J 29: 1201–1205, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Solin P, Roebuck T, Johns DP, Walters EH, Naughton MT. Peripheral and central ventilatory responses in central sleep apnea with and without congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 162: 2194–2200, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stauss HM. Identification of blood pressure control mechanisms by power spectral analysis. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 34: 362–368, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sun SY, Wang W, Zucker IH, Schultz HD. Enhanced peripheral chemoreflex function in conscious rabbits with pacing-induced heart failure. J Appl Physiol 86: 1264–1272, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Triposkiadis F, Karayannis G, Giamouzis G, Skoularigis J, Louridas G, Butler J. The sympathetic nervous system in heart failure physiology, pathophysiology, and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 54: 1747–1762, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vazir A, Dayer M, Hastings PC, McIntyre HF, Henein MY, Poole-Wilson PA, Cowie MR, Morrell MJ, Simonds AK. Can heart rate variation rule out sleep-disordered breathing in heart failure? Eur Respir J 27: 571–577, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yang G, Wu L, Jiang B, Yang W, Qi J, Cao K, Meng Q, Mustafa AK, Mu W, Zhang S, Snyder SH, Wang R. H2S as a physiologic vasorelaxant: hypertension in mice with deletion of cystathionine gamma-lyase. Science 322: 587–590, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]