Aspirin is an established effective anti-platelet and anti-inflammatory agent.1 In a meta-analysis of trials of aspirin in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events, aspirin reduced the number of strokes by 20%.2 The data for long-term primary prevention is less clear but many guidelines recommend its use for some middle age and elderly men and for women aged 65 or older.3 It has been suggested that the use of lower dose aspirin might mitigate some of the bleeding complications attendant with aspirin use, but there remains uncertainty about the cardiovascular protectiveness at lower doses. For example, the Physicians’ Health Study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial designed to determine whether low-dose aspirin (325 mg every other day) decreased cardiovascular mortality and whether beta carotene reduced the incidence of cancer. This trial demonstrated a conclusive reduction in the risk of myocardial infarction, but the evidence concerning stroke and total cardiovascular deaths remained inconclusive, partly because of the inadequate numbers of these end points.4

The persistent and well-documented Stroke Belt region of the United States has a 40% to 50% higher stroke mortality than other regions.5, 6 Within the Stroke Belt, there is substantial heterogeneity in stroke mortality, where a region along the coastal plain of North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia (the “Buckle of Stroke Belt”) having a stroke mortality nearly twice the national average.7, 8 The increased relative risk in the Stroke Belt is persistent, with recent reports indicating a 43% higher odds of prevalent stroke in the Southeastern US, and a racial disparity in stroke is well documented.9,10

We previously reported data on prevalent aspirin use by race and geographic region of the US and the use of aspirin taken for primary prophylaxis.11 In that paper, we postulated that differences between rates of aspirin use might represent one possible contributor to the racial and geographic differences in stroke risk, but our cross-sectional analysis showed that aspirin use was more common in the Stroke Belt compared to the rest of the country, suggesting that differential aspirin use in the Stroke Belt was an unlikely explanation for geographic disparities in stroke. We did observe a higher use of prophylactic aspirin in whites vs blacks. Herein, using the same cohort with prospective follow-up, we evaluate the association of baseline prophylactic aspirin use with subsequent stroke, including assessment of racial, sex, and geographic differences.

METHODS

Study Population

The Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study is a national, population-based, longitudinal cohort study with oversampling of African Americans (AAs) and persons living in the Stroke Belt region of the United States. Between January 2003 and October 2007, 30,239 individuals were enrolled, including race groups (42% AA, 58% white), and both sexes (45% men and 55% women). The sample includes 21% of participants from the Stroke Belt Buckle (coastal plain region of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia), 35% from the Stroke Belt states (remainder of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, plus Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana), and the remaining 44% from the other 40 contiguous states (referred to as non-Belt). REGARDS participants were selected from commercially available lists (Genesys). A letter and brochure informed participants of the study and a follow-up phone call introduced the study and solicited participation. During that call, verbal consent was obtained and a 45-minute questionnaire was administered. The verbal consent included agreement to participate in a subsequent in-person examination. The telephone response rate was 33% and the cooperation rate was 49% (similar to other reported epidemiologic studies).12 Demographic information and medical history including a history of cardiovascular disease and risk factors was obtained by trained interviewers using a computer assisted telephone interview (CATI). Participants were considered to be enrolled in the study if they completed the 45-minute telephone questionnaire and the in-person physical examination. The exam included anthropometric and blood pressure measurements, blood samples, and an electrocardiogram conducted 3-4 weeks after the telephone interview. Written consent was obtained during the in-person visit. Participants or their proxies were contacted by telephone at 6-month intervals for identification of medical events. Medical records were obtained for suspected strokes, and were reviewed by at least 2 physician members of a committee of stroke experts. Stroke events were defined following World Health Organization (WHO) definition, and further classified as ischemic or hemorrhagic. Incident stroke was defined as the first occurrence of physician-adjudicated stroke. The study methods were reviewed and approved by all involved Institutional Review Boards. Additional methodological details are provided elsewhere.8

Analysis Methods

The primary goal of the analysis was to assess differences in stroke incidence by prophylactic aspirin usage. The primary independent variable was aspirin use. A participant was considered a “regular aspirin user” if they answered affirmatively to the question “Are you currently taking aspirin or aspirin containing products regularly, that is, at least two times each week?” (Those who were unsure of their aspirin use were also read a list of common aspirin containing products). Among these regular aspirin users, those answering affirmatively to: “For what purpose are you taking aspirin? Is it to reduce the chance of a heart attack or stroke?” were considered prophylactic aspirin users for the primary analysis. Those answering affirmatively to the following questions: “For what purposes are you taking aspirin? Is it to relieve pain?” were considered as taking aspirin for pain relief and these participants were analyzed as aspirin users in a sensitivity analysis. Those with a self-reported previous history of stroke and those regularly taking aspirin more than 2x per week for pain relief were excluded from the primary analyses. Univariate differences were then tested using the chi-square test. Incremental Cox proportional hazards models were used to test the impact that potential confounding variables had on these associations. Models were used to estimate the risk associated with prophylactic aspirin treatment. We first adjusted for demographic factors (age, race, sex, and region), then added indices of socioeconomic status (income and education), then perceived general health, CVD risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, cigarette smoking and alcohol use). A separate model included demographic and socioeconomic factors and the Framingham Stroke Risk Score (FSRS), rather than the individual risk factors. We also adjusted for baseline CHD.

To further assess the robustness of our results we conducted a series of additional analyses, including an analysis of high-risk subgroups (including those with a previous history of stroke), and an analysis of regular aspirin use for other indications as the exposure combined with prophylactic aspirin use. Statistical calculations were carried out with SAS version 9.2. Approximately 90% of medical records for suspected strokes was retrieved and adjudicated at the time of this analysis. Multiple imputation techniques were used to avoid potential bias from differential retrieval of medical records as previously reported.13 Medication adherence, assessed using the validated Morisky scale was also included as a separate variable.14 Finally, we conducted a propensity score analysis (the propensity score included predictors for age, race, sex, history of stroke, history of heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, cigarette smoking, education, income, self-reported health) to confirm concordance of the approach with the covariate-adjustment approach. The HR for aspirin use was 1.02 (95% CI: 0.86 – 1.21) after adjustment for the propensity score, race, sex and age.

The potential for aspirin to be associated with cerebral and gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding was also explored. On the CATI the question was asked “For each time you/he/she stayed as a patient in a hospital, nursing home or rehabilitation center, I need to know the reason, the name and location of where you/he/she stayed, the date and the name of the doctor who treated you/him/her. Since we last spoke to you/him/her?

What was the reason you/he/she were/was admitted?

Stroke/brain aneurysm/TIA

Heart-related condition

Cancer

Other Specify: If answered other, we searched the free text ”other specify“

response for the word ”bleed“ and then two of the authors classified each of the bleeds as a GI or not. For cerebral bleeds, the hospital records were reviewed by an expert central adjudication committee.

RESULTS

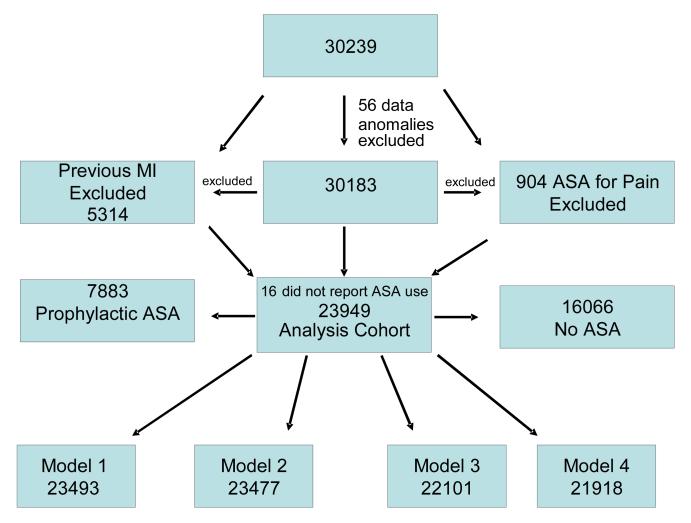

The total REGARDS sample consisted of 30,239 subjects, 30,183 after 56 with data anomalies were excluded. For the primary analysis 1,930 with pre-baseline stroke and 1,019 subjects regularly taking aspirin for indications other than vascular disease prophylaxis, and 15 with missing data on aspirin use were excluded. As seen in Figure 1, this left an analysis cohort of 27,219 with a mean follow-up time of 4.6 years (maximum of 7.6 years). There were 17,042 who were not taking prophylactic aspirin, and 10,177 that were. Age, sex, racial group, region, and other demographic and baseline variables stratified by prophylactic aspirin use, non-prophylactic use, and regular aspirin use is listed in Table 1. There were 478 incident stroke cases over a mean follow-up of 4.6 years. Covariates used in the analysis were missing in small numbers for each model, reducing the sample size to 26,734 for model 1, 26,720 for model 2, 25,186 for model 3, and 24,195 (991 were missing the FSRS) for model 4.

Figure 1.

The Exclusionary Cascade

Table 1.

Baseline aspirin use broken down by prophylactic vs not prophylactic treatment

| Overall | Not Prophylactic Asprin User |

Prophylactic Aspirin User |

p-value of prophylactic aspirin users vs. no |

Not Regular Asprin User |

Regular Aspirin User |

p-value of regular aspirin users vs. no |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Overall | 27219 | 17042 | 62.6 | 10177 | 37.4 | 16361 | 60.1 | 10858 | 39.9 | |||

| Incident Stroke | ||||||||||||

| No | 23446 | 86.1 | 15757 | 67.2 | 7689 | 32.8 | <.0001 | 12823 | 54.7 | 10623 | 45.3 | <.0001 |

| Yes | 478 | 1.8 | 284 | 59.4 | 194 | 40.6 | 243 | 50.8 | 235 | 49.2 | ||

| Region | ||||||||||||

| Belt and Buckle | 15144 | 55.6 | 9399 | 62.1 | 5745 | 37.9 | 0.0369 | 9014 | 59.5 | 6130 | 40.5 | 0.0268 |

| Non Belt | 12075 | 44.4 | 7643 | 63.3 | 4432 | 36.7 | 7347 | 60.8 | 4728 | 39.2 | ||

| Race | ||||||||||||

| Black | 11148 | 41.0 | 7584 | 68.0 | 3564 | 32.0 | <.0001 | 7299 | 65.5 | 3849 | 34.5 | <.0001 |

| White | 16071 | 59.0 | 9458 | 58.9 | 6613 | 41.1 | 9062 | 56.4 | 7009 | 43.6 | ||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | 12164 | 44.7 | 6742 | 55.4 | 5422 | 44.6 | <.0001 | 6387 | 52.5 | 5777 | 47.5 | <.0001 |

| Female | 15055 | 55.3 | 10300 | 68.4 | 4755 | 31.6 | 9974 | 66.3 | 5081 | 33.7 | ||

| Age Group | ||||||||||||

| 45-55 | 3509 | 12.9 | 2809 | 80.1 | 700 | 19.9 | <.0001 | 2768 | 78.9 | 741 | 21.1 | <.0001 |

| 55-65 | 10535 | 38.7 | 6890 | 65.4 | 3645 | 34.6 | 6694 | 63.5 | 3841 | 36.5 | ||

| 65-75 | 8660 | 31.8 | 4866 | 56.2 | 3794 | 43.8 | 4603 | 53.2 | 4057 | 46.8 | ||

| 75-85 | 3997 | 14.7 | 2195 | 54.9 | 1802 | 45.1 | 2038 | 51.0 | 1959 | 49.0 | ||

| 85+ | 518 | 1.9 | 282 | 54.4 | 236 | 45.6 | 258 | 49.8 | 260 | 50.2 | ||

| Income | ||||||||||||

| <$20K | 4674 | 17.2 | 3034 | 64.9 | 1640 | 35.1 | <.0001 | 2882 | 61.7 | 1792 | 38.3 | 0.0145 |

| $20K-$35 | 6523 | 24.0 | 4046 | 62.0 | 2477 | 38.0 | 3879 | 59.5 | 2644 | 40.5 | ||

| $35K-$75K | 8223 | 30.2 | 5117 | 62.2 | 3106 | 37.8 | 4931 | 60.0 | 3292 | 40.0 | ||

| $75K+ | 4468 | 16.4 | 2696 | 60.3 | 1772 | 39.7 | 2621 | 58.7 | 1847 | 41.3 | ||

| Missing income | 3331 | 12.2 | 2149 | 64.5 | 1182 | 35.5 | 2048 | 61.5 | 1283 | 38.5 | ||

| Years of education | ||||||||||||

| < High School | 3203 | 11.8 | 2020 | 63.1 | 1183 | 36.9 | <.0001 | 1903 | 59.4 | 1300 | 40.6 | <.0001 |

| High School | 7001 | 25.7 | 4449 | 63.5 | 2552 | 36.5 | 4254 | 60.8 | 2747 | 39.2 | ||

| Some College | 7322 | 26.9 | 4710 | 64.3 | 2612 | 35.7 | 4543 | 62.0 | 2779 | 38.0 | ||

| College+ | 9677 | 35.6 | 5850 | 60.5 | 3827 | 39.5 | 5651 | 58.4 | 4026 | 41.6 | ||

| Perceived health | ||||||||||||

| Excellent | 4558 | 16.8 | 3039 | 66.7 | 1519 | 33.3 | <.0001 | 2924 | 64.2 | 1634 | 35.8 | <.0001 |

| Very Good | 8529 | 31.4 | 5450 | 63.9 | 3079 | 36.1 | 5243 | 61.5 | 3286 | 38.5 | ||

| Good | 9535 | 35.1 | 5848 | 61.3 | 3687 | 38.7 | 5613 | 58.9 | 3922 | 41.1 | ||

| Fair | 3744 | 13.8 | 2224 | 59.4 | 1520 | 40.6 | 2118 | 56.6 | 1626 | 43.4 | ||

| Poor | 798 | 2.9 | 445 | 55.8 | 353 | 44.2 | 430 | 53.9 | 368 | 46.1 | ||

| Hypertension | ||||||||||||

| No | 11460 | 42.2 | 8107 | 70.7 | 3353 | 29.3 | <.0001 | 7879 | 68.8 | 3581 | 31.2 | <.0001 |

| Yes | 15691 | 57.8 | 8897 | 56.7 | 6794 | 43.3 | 8446 | 53.8 | 7245 | 46.2 | ||

| Diabetes | ||||||||||||

| No | 20698 | 79.0 | 13488 | 65.2 | 7210 | 34.8 | <.0001 | 12995 | 62.8 | 7703 | 37.2 | <.0001 |

| Yes | 5512 | 21.0 | 2855 | 51.8 | 2657 | 48.2 | 2688 | 48.8 | 2824 | 51.2 | ||

| Dyslipidemia | ||||||||||||

| No | 10861 | 41.5 | 7805 | 71.9 | 3056 | 28.1 | <.0001 | 7513 | 69.2 | 3348 | 30.8 | <.0001 |

| Yes | 15340 | 58.6 | 8509 | 55.5 | 6831 | 44.5 | 8144 | 53.1 | 7196 | 46.9 | ||

| Smoking status | ||||||||||||

| Never | 12445 | 45.9 | 8122 | 65.3 | 4323 | 34.7 | <.0001 | 7838 | 63.0 | 4607 | 37.0 | <.0001 |

| Past | 10812 | 39.9 | 6247 | 57.8 | 4565 | 42.2 | 5940 | 54.9 | 4872 | 45.1 | ||

| Current | 3853 | 14.2 | 2597 | 67.4 | 1256 | 32.6 | 2510 | 65.1 | 1343 | 34.9 | ||

| Alcohol use | ||||||||||||

| Never | 8204 | 30.1 | 5330 | 65.0 | 2874 | 35.0 | <.0001 | 5092 | 62.1 | 3112 | 37.9 | <.0001 |

| Past | 4710 | 17.3 | 2924 | 62.1 | 1786 | 37.9 | 2793 | 59.3 | 1917 | 40.7 | ||

| Current | 14305 | 52.6 | 8788 | 61.4 | 5517 | 38.6 | 8476 | 59.3 | 5829 | 40.7 | ||

| Framingham stroke score | ||||||||||||

| 0-5 | 6247 | 25.0 | 4882 | 78.1 | 1365 | 21.9 | <.0001 | 4807 | 76.9 | 1440 | 23.1 | <.0001 |

| 5-10 | 6243 | 24.9 | 4098 | 65.6 | 2145 | 34.4 | 3954 | 63.3 | 2289 | 36.7 | ||

| 10-20 | 6267 | 25.0 | 3580 | 57.1 | 2687 | 42.9 | 3404 | 54.3 | 2863 | 45.7 | ||

| 20+ | 6280 | 25.1 | 3093 | 49.3 | 3187 | 50.7 | 2853 | 45.4 | 3427 | 54.6 | ||

In univariate analyses (Table 2) prophylactic aspirin use was associated with an increased risk of incident stroke (HR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.16 - 1.62, data not shown); however, this difference was not apparent with adjustments for confounders (HR 1.06, 95% CI 0.86;1.32). There was a higher incidence of stroke in African Americans compared to whites (HR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.30 - 1.84) but, in the most parsimonious model, this difference was statistically absent (HR = 1.17 95% CI: 0.97 - 1.42- data not shown}. Sensitivity analysis included the 1,019 participants taking aspirin for pain relief, but did not yield different associations (Table 2), nor did adjustment for medicine adherence (data not shown).

Table 2.

Hazard Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for time to stroke

| Demographics | Demographics + SES | Demographics + SES + RF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regular Aspirin Vs. No | 1.14 (0.96 - 1.36) | 1.15 (0.97 -1.37) | 1.07 (0.89 - 1.28) |

| Prophylactic Asprin Users Vs. No | 1.16 (0.97 -1.38) | 1.17 (0.98 - 1.40) | 1.08 (0.90 - 1.30) |

| Non-Prophylatic Asprin vs. No | 0.88 (0.52 - 1.49) | 0.86 (0.50 - 1.46) | 0.90 (0.53 - 1.55) |

Demographics-Region (Stroke Region vs. Not), Race (Black vs. White), Gender (Male vs. Female), Age (45-55, 55-65, 65-75, 75-85, 85+)

SES (Socioeconomic Status) - Income (Missing, <$20,000, 20,000-34,999, 35,000-74,999, 75,000+) , Education (Less Than High School, High School, Some college, college graduate)

RF (Risk Factors) - Self Reported Health (Excellent, Very Good, Good, Fair, Poor), Hypertensive (Yes, No), Diabetic (Yes, No), Dyslipidemic (Yes, No), Smoker (Never, Past, Current) Alcohol (Never, Past, Current), prevalent CHD

Of those using aspirin for prophylaxis, the majority (over 70%) were utilizing low dose (180 mg/d or less). Use of low dose aspirin was similar in the stroke belt vs. non-belt, more common in African Americans compared to whites (25% vs 22% p 0.03) and in men vs women (26% vs 20%). Since non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) have been reported to ameliorate the anti-platelet effects of aspirin, we also assessed its concomitant use. Few participants used concomitant aspirin and NSAIDs (4.4%), with a slightly higher concomitant use among stroke belt residents than in other regions (4.8% versus 4.0%), and higher concomitant use among whites than African Americans (5.4% versus 3.1%). There were also relatively small differences in concomitant use among race, age groups, income, and other confounding factors, while adjusting for medical adherence did not affect the use of aspirin on stroke (Data not shown).

Recent guidelines have suggested subsets that might benefit from prophylactic aspirin use for stroke such as women > 65 yo, and women who are either high risk or diabetic, but our secondary analysis failed to show a significant association of prophylactic aspirin use and stroke risk in these groups. Finally, although the primary analysis was incident stroke, we hypothesized that those at highest risk for a stroke were those with a prior stroke, but again, prophylactic aspirin was not associated with risk of recurrent stroke risk (HR 0.92, 0.65:1.31 in the adjusted model – Table 3).). The propensity score approach was concordant with these results, failing to show prophylactic aspirin to have an association with stroke risk.

Table 3.

Stratification of prophylactic aspirin use by baseline risk

| Group | Model 1 Prophylaxtic Aspirin, Region,Race, Gender, Age |

Model 2 Model 1 + income, education |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ****All Hazard Ratios and Limits are Prophylatic Aspririn Users vs. Not | ||||||

| Hazard Ratio |

Lower Limit |

Upper Limit |

Hazard Ratio |

Lower Limit |

Upper Limit |

|

| Previous History of Stroke | 0.93 | 0.66 | 1.31 | 0.92 | 0.65 | 1.31 |

| Q4 Framingham Risk Sum | 0.95 | 0.75 | 1.22 | 0.96 | 0.75 | 1.23 |

| Q3 Framingham Risk Sum | 1.08 | 0.78 | 1.49 | 1.08 | 0.78 | 1.5 |

| Q2 Framingham Risk Sum | 0.67 | 0.4 | 1.14 | 0.68 | 0.4 | 1.15 |

| Q1 Framingham Risk Sum | 2.26 | 0.91 | 5.59 | 2.27 | 0.92 | 5.62 |

There were 148 hospitalized GI bleeds and 58 cerebral hemorrhages, the latter documented by central adjudication using standard definitions (an incident stroke was defined as: rapid onset of a persistent neurologic deficit attributable to an obstruction or rupture of the arterial system; deficit is not known to be secondary to brain trauma, tumor, infection, or other non-ischemic cause; deficit must last more than 24 h, unless death supervenes or there is a demonstrable lesion compatible with acute stroke on computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging). The cerebral bleeds in all models were not significantly greater in the aspirin group.

DISCUSSION

In this study, aspirin used for primary prophylaxis was not associated with incident stroke (hemorrhagic and/or ischemic), after accounting for stroke risk factors. We did not observe an increase in hemorrhagic stroke in aspirin users. Based on these results along with many (but not all) studies, there appears to be insufficient evidence to determine that aspirin reduces the risk of stroke in the general population. Likewise, we failed to identify a benefit of aspirin and stroke risk reduction for any subgroups.

In a recently published guideline addressing the primary prevention of stroke, it was noted that the US Preventive Services Task Force recommended aspirin at a dosage of 75 mg/d for cardiac prophylaxis for persons whose 5-year risk for coronary heart disease is ≥ 3%.15 The American Heart Association guideline for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and stroke agrees with the US Preventive Services Task Force report on the use of aspirin in persons at high risk but uses a ≥10% risk per 10 years to balance the risk/benefit.16 The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) published a guideline document in 2012 and offered only a weak recommendation supporting aspirin as primary prevention in adults over the age of 50. They noted that the cardiovascular benefit and bleeding risk is ”pretty much balanced.“17

In the present study, we analyzed the association of aspirin use with risk of incident stroke using several models and risk groups, and in contrast to the ACCP analyses, found no benefit of prophylactic aspirin and no increased bleeding. The Japanese Primary Prevention of Atherosclerosis With Aspirin for Diabetes (JPAD) Trial randomized 2539 patients with type 2 diabetes without a history of atherosclerotic disease (including stroke) to low-dose aspirin (81 or 100 mg/d) or no aspirin. Low dose aspirin had no effect on the trial’s primary end point and no effect on total cerebrovascular events (2.2% with aspirin versus 2.5% with no aspirin).18 The Prevention of Progression of Arterial Disease and Diabetes (POPADAD) trial also found no effect of aspirin treatment on the primary end point or on fatal stroke.19 The Canadian antiplatelet guidelines were among the first to advise against routine use of aspirin for people without evidence of vascular disease. But the guidelines offer flexibility stating that ”in special circumstances in men and women without evidence of manifest vascular disease in whom vascular risk is considered high and bleeding risk low, aspirin 75-162 mg daily may be considered“.19 The Primary cARe AuDIt of Global risk Management (PARADIGM) a Canada-wide observational registry enrolled 3015 generally healthy, middle-aged adults being treated by general practitioners and excluded anyone with diabetes or vascular disease. A medication review of this registry showed that roughly 13.5% were taking aspirin, 80% of who were in the low-intermediate risk category.

Consistent with other published reports of the use of low dose aspirin for primary prevention, we observed no difference in hemorrhagic stroke between aspirin users and non-users.18 In a recent meta-analysis reported by Seshasai et al20 involving over 100 000 participants (with a mean (SD) follow-up of 6.0 (2.1) years s), aspirin treatment reduced total CVD events by 10% (OR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.85-0.96; number needed to treat, 120), driven primarily by reduction in nonfatal myocardial infarction (OR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.67-0.96; number needed to treat, 162). There was no significant reduction in CVD death (OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.85-1.15) but there was increased risk of nontrivial bleeding events (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.14-1.50; number needed to harm, 73) that offset the small observed benefit. In the studies included in their meta-analysis, there was a wide range of aspirin doses (500mg daily to 100 mg on alternate days). In our study, 75% of subjects reported taking low dose aspirin (180mg/d) and none reported more than 300 mg/d. Beyond those differences and differences in the study populations, we have no explanation for the disparity in observed occurrence of bleeding episodes.

Our study has several limitations worth noting. As noted above perhaps the greatest is the possibility for ”confounding by indication“ that was not completely captured in the covariate adjustments (ie residual confounding). We attempted to account for this higher risk with covariate adjustment, but it is possible that our efforts did not capture the all of the reasons that they are at higher risk. These adjustments did substantially explain an observed univariately significant association of aspirin use and stroke risk (suggesting that such indications are likely active); however, the attenuation was not sufficient to document a protective effect for aspirin use. Also, a propensity score analysis did not significantly affect the time to stroke. Some risk factors (non laboratory measured variables) were based on self-report (although this is common to many epidemiologic studies), and individuals without telephones were necessarily excluded from selection into the study population. These excluded individuals may be of lower socioeconomic status and, therefore, may have different risk factor profiles than those included in this analysis (a criticism that could also apply to clinical trials). Also, the mean follow-up time of 4.6 years may be insufficient to demonstrate an association. Finally, participant usage of aspirin was also by self-report as was medication adherence (although we used a validated instrument to estimate this).

In conclusion, an association between prophylactic aspirin use and stroke risk, was likely a product of ”confounding by indication“ (i.e., those with heavier risk factor profiles taking aspirin to avoid stroke) and was largely mediated by covariate adjustment. In the multivariable models, aspirin use for primary prevention did not affect incident stroke, and there were no race, sex or regional differences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

There are no conflicts to report for any of the authors, except Dr. George Howard. Dr. Howard is on the Executive Committee for the Aspirin to Reduce Risk of Initial Vascular Events (ARRIVE) Study, sponsored by Bayer.

Contributor Information

Stephen P Glasser, Division of Preventive Medicine and Department of Epidemiology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

Martha K. Hovater, Department of Biostatics, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL

Daniel T. Lackland, Department of Neurosciences and Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC.

Mary Cushman, Department of Medicine, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT.

George Howard, Department of Biostatistics, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

Virginia J Howard, Department of Epidemiology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

References

- 1.Ridker PM, Cushman M, Stampfer MJ, Tracy RP, Hennekens CH. Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. The New England journal of medicine. 1997;336:973–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704033361401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antithrombotic Trialists” Collaboration Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. Bmj. 2002;324:71–86. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Preventive Services Task Force Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: recommendation and rationale. Annals of internal medicine. 2002;136:157–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-2-200201150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steering Committee of the Physicians’ Health Study Research Group Final Report on the Aspirin Component of the Ongoing Physicians’ Health Study. New England Journal of Medicine. 1989;321:129–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907203210301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein LB, Adams R, Alberts MJ, et al. Primary prevention of ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council: cosponsored by the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease Interdisciplinary Working Group; Cardiovascular Nursing Council; Clinical Cardiology Council; Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism Council; and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2006;37:1583–633. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000223048.70103.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pleis JR, et al. Summary health statistics for US Adults: National Health interview Survey, 2009. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2010;10(249) Tables 1 and 2 have data by regions defined as Northeast, Midwest. South and West, Midwest, South. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casper ML, Wing S, Anda RF, Knowles M, Pollard RA. The shifting stroke belt. Changes in the geographic pattern of stroke mortality in the United States, 1962 to 1988. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1995;26:755–60. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.5.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, et al. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25:135–43. doi: 10.1159/000086678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Regional and racial differences in prevalence of stroke-23 states and District of Columbia, 2003. MMWR. 2003;54:481–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fullerton HJ, JS E, SC J. Pediatric Stroke Belt: Geographic Variation in Stroke Mortality in US Children. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2004;35:1570–3. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000130514.21773.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glasser S, Cushman M, Prineas RJ, et al. Does Differential Prophylactic Aspirin Use Contrigute to Racial and Geographic Disparities in Stroke? Preventive medicine. 2008;47:161–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galea S, Tracy M. Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:643–53. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howard G, McClure LA, Moy CS, et al. Imputation of incident events in longitudinal cohort studies. American journal of epidemiology. 2011;174:718–26. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein LB, Bushnell CD, Adams RJ, et al. Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2011;42:517–84. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3181fcb238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearson TA, Blair SN, Daniels SR, et al. American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee AHA Guidelines for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke: 2002 Update: Consensus Panel Guide to Comprehensive Risk Reduction for Adult Patients Without Coronary or Other Atherosclerotic Vascular Diseases. Circulation. 2002;106:388–91. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000020190.45892.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guyatt GH, Akl EA, Crowther M, et al. Antithrombotic therapy and prevventionof thrombosis, 9th Ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;11((2)(Suppl)):7S–47S. doi: 10.1378/chest.1412S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogawa H, Nakayama M, Morimoto T, et al. Low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of atherosclerotic events in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300:2134–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belch J, MacCuish A, Campbell I, et al. The prevention of progression of arterial disease and diabetes (POPADAD) trial: factorial randomised placebo controlled trial of aspirin and antioxidants in patients with diabetes and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease. BMJ. 2008;337:a1840. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seshasai SR, Wijesuriya S, Sivakumaran R, et al. Effect of Aspirin on Vascular and Nonvascular Outcomes: Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Archives of internal medicine. 2012;172:209–16. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]