Abstract

The identification of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), fumarate hydratase (FH), and isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutations in human cancers has rekindled the idea that altered cellular metabolism can transform cells. Inactivating SDH and FH mutations cause the accumulation of succinate and fumarate, respectively, which can inhibit 2-oxoglutarate (2-OG)-dependent enzymes, including the EglN prolyl 4-hydroxylases that mark the HIF transcription factor for polyubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation 1. Inappropriate HIF activation is suspected of contributing to the pathogenesis of SDH-defective and FH-defective tumors but can suppress tumor growth in some other contexts. IDH1 and IDH2, which catalyze the interconversion of isocitrate and 2-OG, are frequently mutated in human brain tumors and leukemias. The resulting mutants display the neomorphic ability to convert 2-OG to the R-enantiomer of 2-hydroxyglutarate (R-2HG) 2, 3. Here we show that R-2HG, but not S-2HG, stimulates EglN activity leading to diminished HIF levels, which enhances the proliferation and soft agar growth of human astrocytes.

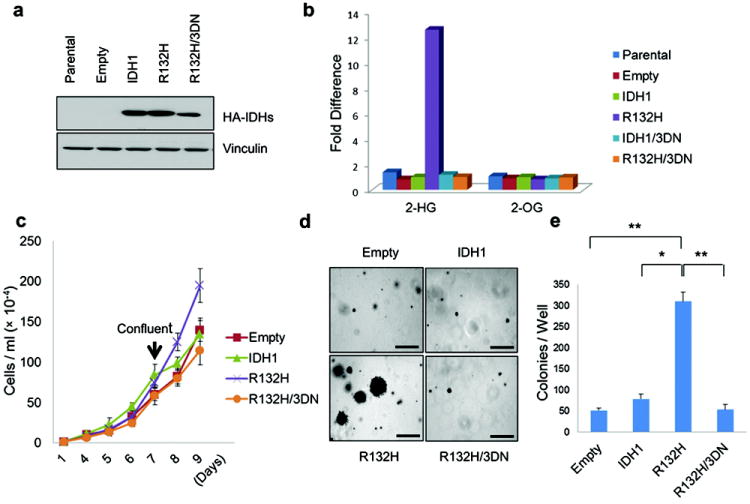

To study the role of IDH mutations in brain tumors, we stably infected immortalized human astrocytes with retroviral vectors encoding hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged versions of wild-type IDH1, a tumor-derived mutant (IDH1 R132H) 2,3, or an IDH1 R132H variant in which three conserved aspartic acid residues within the IDH1 catalytic domain were replaced with asparagines (R132H/3DN) (Fig 1a and Supplementary Fig 1). As expected, R-2HG levels, but not S-2HG levels, were dramatically increased in the cells producing IDH1 R132H but not in cells producing the R132H/3DN variant (Fig 1b, Supplementary Fig 2). In multiple independent experiments the IDH1 R132H cells acquired a proliferative advantage relative to cells producing the other versions of IDH1 beginning around passage 14, manifested as increased proliferation at confluence (Fig 1c) and the ability to form macroscopic colonies in soft agar (Fig 1d and e).

Figure 1. Oncogenic Properties of IDH1 R132H.

a,b, Anti-HA immunoblot (a) and LC-MS analysis (b) of immortalized human astrocytes (passage 4) infected with retroviruses encoding HA-tagged versions of the indicated IDH1 variants. c,d, In vitro proliferation under standard culture conditions (c) or in soft agar (d)(passage 23). Bars in (d) = 0.5 mm. e, Number of macroscopic soft agar colonies in (d) (*P<0.01, **P<0.005). Error bars, s.d.; n=3.

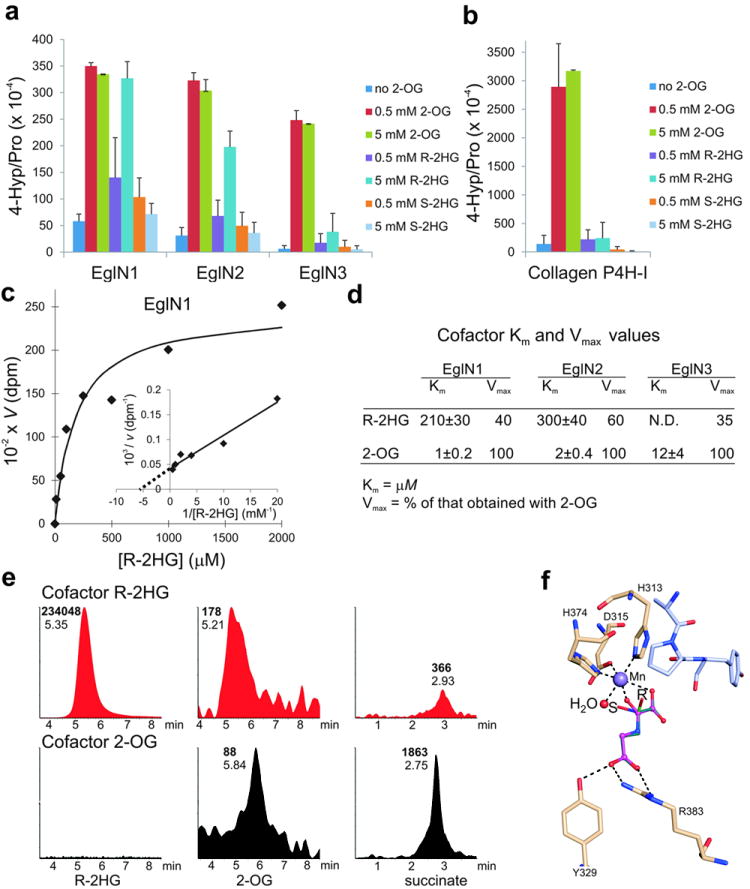

Consistent with recent reports, we found that both R-2HG and S-2HG inhibit a number of 2-OG-dependent enzymes in vitro 4-6, including the collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylases, the TET1 and TET2 methyl cytosine hydroxylases, the HIF asparaginyl hydroxylase FIH and the JMJD2D histone demethylase, with S-2HG being a more potent inhibitor than R-2HG (Supplementary Fig 3 and data not shown). S-2HG was also a micromolar to low millimolar inhibitor of the three mammalian HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylases (EglN1, EglN2, and EglN3) under standard assay conditions, which included 10 μM 2-OG (Supplementary Fig 4). In contrast, R-2HG was not an effective EglN inhibitor (IC50 values >5 mM) (Supplementary Fig 4). Moreover, we discovered unexpectedly that R-2HG, but not S-2HG, promoted EglN1 and EglN2 activity, and to a lesser extent EglN3 activity, at tumor-relevant concentrations (low mM) in reactions that lacked exogenous 2-OG (Fig 2a, c, d and Supplementary Fig 5a and b). This was specific because R-2HG did not promote collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylase activity (Fig 2b) or JMJD2D histone demethylase activity (data not shown). Similar results were obtained with EglN1 purified from either insect cells or E. coli and with a heat-inactivated HIF polypeptide substrate (Supplementary Fig 6), making it unlikely that ability of R-2HG to promote EglN activity required a contaminating enzyme.

Fig. 2. R-2HG can serve as an EglN cosubstrate.

a, b, In vitro prolyl 4-hydroxylation assays conducted with recombinant EglNs (a) and collagen P4H-I (b) in the presence of the indicated amounts of 2-OG or 2HG. L-[2,3,4,5-3H]proline-labeled HIF1α oxygen-dependent degradation domain (ODDD) (a) and [14C]proline-labeled protocollagen (b) were used as substrates. Enzymes were produced in insect cells using baculoviruses and affinity-purified. Error bars, s.d.; n = 3-4.

c, d, Km and Vmax values for R-2HG for EglN family members. Km and Vmax values for 2-OG 21 are included for comparison.

e, LC-MS analysis of succinate, 2-OG and R-2HG from enzymatic reactions with EglN1, HIF1α oxygen-dependent degradation domain (ODDD) polypeptide and either 5 mM R-2HG (red) or 80 μM 2-OG (black) as cofactors. Numbers next to each peak indicate elution times (plain font) and peak areas (bold font). No peaks above background were detected in samples in which 2-OG and R-2HG were both omitted (data not shown).

f, Model of R-2HG (green) and S-2HG (cyan) bound to the active site of EglN1. N-oxalylglycine (magneta) bound in the original structure 29 is shown for comparison. The active site water molecule, which has been shown to be the O2 binding site 30, is shown in red and the peptide substrate in light blue. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by dash lines.

To determine how R-2HG might promote EglN activity, we monitored the EglN1 prolyl 4-hydroxylase reaction using LC-MS. 2-OG and succinate were detected when catalytically active EglN1 was incubated with 5 mM R-2HG and a recombinant HIF1α polypeptide, suggesting that EglN1 can oxidize R-2HG to 2-OG, which is then decarboxylated to succinate during the hydroxylation reaction (Fig 2e and Supplementary Fig 5c). In support of this model, 13C-labelled succinate was generated in EglN hydroxylation assays that contained uniformly labelled 13C-R-2HG (Supplementary Fig 5d).

Consistent with the idea that R-2HG can substitute for 2-OG as a cosubstrate, addition of increasing amounts of R-2HG to EglN1 assays containing 10 μM 2-oxo-[1-14C]glutarate progressively decreased the release of 14CO2 without decreasing the prolyl hydroxylation of HIF1α, even at concentrations as high as 100 mM (Supplementary Fig 7). Modeling of 2HG bound to the active site of EglN1 predicts that binding of the S enantiomer, but not the R enantiomer, would prevent the subsequent recruitment of oxygen to the active site, perhaps accounting for the qualitatively different effects of the two enantiomers on EglN activity (Fig 2f and Supplementary Fig 5e).

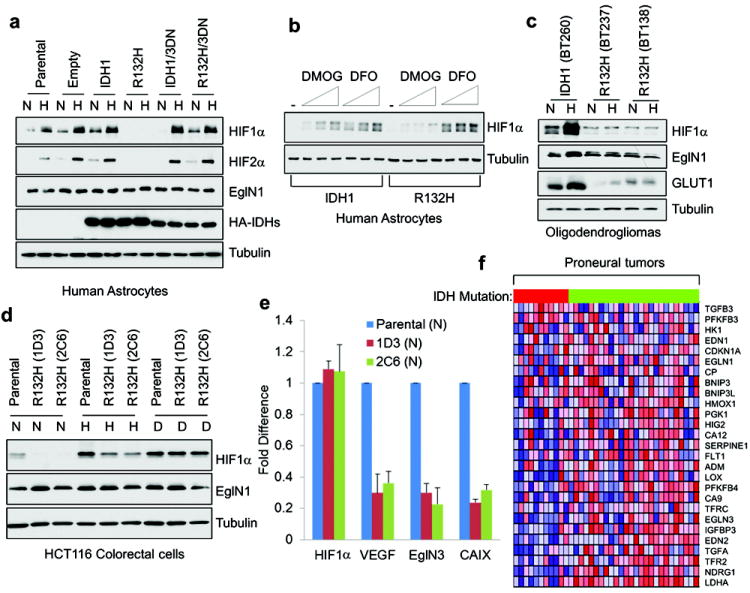

To ask if these findings were relevant in vivo we examined the HIF levels in IDH1 mutant cells. In keeping with our biochemical results, HIF1α and HIF2α protein levels were reproducibly lower in midpassage (p9-p15) human astrocytes producing IDH1 R132H relative to control astrocytes (Fig 3a), due at least partly to increased HIFα hydroxylation and diminished protein stability (Supplementary Figs 8 and 9), and were associated with lower levels of the HIF-responsive mRNAs encoding VEGF, GLUT1, and PDK1 (Supplementary Fig 10a). Oxygen consumption and ROS production, which can also affect HIF levels and the HIF response, were not measurably altered in the IDH1 mutant cells (Supplementary Fig 11). R132H-expressing cells were relatively resistant to the 2-OG competitive antagonist DMOG, but not to the iron chelator deferoxamine (DFO) (Fig 3b), consistent with R-2HG acting as a 2-OG agonist in intact cells. In later passage (> p20) IDH1 R132H NHA cells HIF levels began to normalize despite persistent production of the exogenous IDH1 protein and R-2HG (Supplementary Fig 12), possibly due to adaptive HIF-responsive feedback loops such as those involving EglN3 and miR-155 1,7. These cells, however, retained the ability to form colonies in soft agar (data not shown) and remained addicted to EglN activity (see below).

Fig 3. HIF activity is diminished in IDH mutant cells.

a-d, Immunoblot analysis of immortalized human astrocytes (passage 10) (a,b), oligodendroglioma cells (c) and HCT116 colorectal cells (d) expressing the indicated IDH1 variants grown under 21% (N) or 7.5% (H) oxygen for 24 hours prior to lysis or under 21% oxygen in presence of DFO (D). In (b) cells grown under 21% oxygen were treated with increasing amounts of DMOG or DFO for 16 hours prior to lysis. e, Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of cells in (d) under normoxic conditions. Error bars, s.d. n=3. f, Heat map depicting expression of HIF target genes (blue = lower expression and red = higher expression) in proneural tumors clustered based on IDH status (red = mutant and green = wild-type in horizontal bar atop matrix).

Similarly, the induction of HIF1α and HIF-responsive mRNAs by hypoxia was diminished in two independent cell lines derived from two IDH1 R132H, 1p/19q-codeleted, oligodendrogliomas compared to a control IDH1 wild-type, 1p/19q-codeleted, oligodendroglioma that had been generated in a similar fashion (Fig 3c and Supplementary Fig 10b). Although these three cell lines have similar growth kinetics in vitro (data not shown) they are not isogenic. We therefore also tested two HCT116 colorectal cancer cell sublines wherein the R132H mutation was introduced into the endogenous IDH1 locus by homologous recombination. These sublines also displayed a diminished HIF response compared to wild-type cells unless EglN was pharmacologically (DFO) or genetically (shRNA) inactivated (Fig 3d and 3e and Supplementary Fig 13).

Finally, we asked whether IDH mutational status influenced HIF activity in primary patient astrocytoma samples using the TCGA expression data set 8 and a previously defined HIF-responsive gene expression signature 9. The HIF signature was diminished in proneural tumors, which is the subtype most often associated with IDH mutations 8, relative to other gene expression-defined subtypes of brain cancer (Supplementary Fig 14a and b) and, notably, was diminished in IDH mutant proneural tumors relative to wild-type proneural tumors (Fig 3f and Supplementary Fig 14c). Similar results were obtained with other previously published HIF gene sets and with a manually curated data set (Supplementary Fig 14a and d).

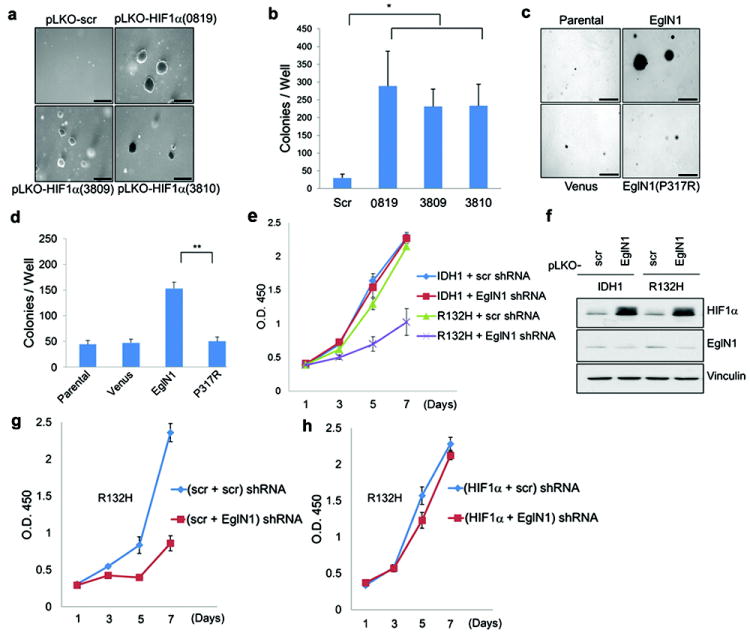

Downregulating HIF1α with 3 independent shRNAs promoted soft agar growth by immortalized human astrocytes after ~ 15 passages (Fig 4a and b and Supplementary Fig 15), as did overproduction of wild-type, but not catalytic-defective, EglN1 (Fig 4c and d and Supplementary Fig 16). Conversely, downregulation of EglN1 with multiple shRNAs inhibited the proliferation of late passage IDH1 R132H cells (Fig 4e and f and Supplementary Fig 17) unless HIF1α was concurrently ablated (Fig 4g and h and Supplementary Fig 18).

Fig 4. Decreased HIF activity contributes to transformation by mutant IDH.

a,c, Soft agar colony formation by human astrocytes after stable infection with lentiviruses encoding the indicated HIF1α shRNAs or scrambled (Scr) shRNA (a) or lentiviruses encoding EglN1, EglN1 (P317R), or venus fluorescent protein (c). Bars = 0.5 mm.

b,d, Number of macroscopic soft agar colonies in (a) and (c), respectively. (*P<0.05, **P<0.005). Error bars, s.d. n=3.

e,f, Proliferation (e) and immunoblot analysis (f) of human astrocytes expressing wild-type or R132H IDH1 and an shRNA against EglN1 (10578) (or scrambled control).

g,h, Proliferation of human astrocytes expressing IDH1 R132H and shRNAs against HIF1α (0819), EglN1 (10578), or both. Scr= scrambled shRNA.

Collectively, these data suggest EglN activation by R-2HG, and subsequent downregulation of HIF1α, contributes to the pathogenesis of IDH mutant gliomas. Our data do not, however, exclude that R-2HG has additional targets, including TET2 and JmjC-containing histone demethylases, that contribute to its ability to transform cells4-6. Indeed, we found that downregulation of TET2 in human astrocytes also promotes soft agar growth (Supplementary Fig 19). Nonetheless, our finding that R-2HG and S-2HG are qualitatively different with respect to EglN might explain the apparent selection for R-2HG in adult tumors, despite the fact that S-2HG is a more potent inhibitor of most of the 2-OG-dependent enzymes tested to date. It should be noted, however, that S-2HG has been linked to neurological abnormalities and brain tumors in children and young adults with germline S-2-HG dehydrogenase mutations 10-12. The pathogenesis of R-2HG-driven tumors linked to somatic IDH mutations in adults and S-2HG-driven tumors linked to inborn errors of metabolism conceivably differ, with the latter possibly reflecting the perturbation of one or more neurodevelopmental programs during embryogenesis.

Nor are our data incompatible with the finding that HIF1α protein levels are increased in IDH mutant tumors relative to normal brain 13. Our data simply suggest that R-2HG quantitatively shifts the dose-response linking HIF activation to hypoxia, leading to a blunted HIF response for a given level of hypoxia. In support of this idea, HIF elevation in IDH mutant tumors is usually confined to areas of necrosis and presumed severe hypoxia 14.

Although HIF is typically viewed as an oncoprotein it can behave as a tumor suppressor in embryonic stem cells 15,16, leukemic cells 17, and brain tumor cells 18,19. For example, Bergers and coworkers showed that HIF1α scores as an oncoprotein when transformed murine astrocytes are grown subcutaneously but as a tumor suppressor when such cells are grown orthotopically 19. This finding, together with our results, raises the possibility that pharmacological inhibition of EglN activity (and the resulting increase in HIF activity) would impair the growth of IDH1 mutant tumors. A caveat, however, is that IDH mutant tumors tend to be relatively indolent 20. It is possible that low levels of HIF1α, while promoting some aspects of transformation, simultaneously suppress other hallmarks of cancer required for aggressive behavior (such as angiogenesis).

The published 2-OG Km values for the EglN family members are below the estimated intracellular 2-OG concentration 21,22, suggesting that 2-OG should not be limiting for EglN activity and that EglN activity would not be enhanced further by R-2HG. A caveat is that a considerable amount of intracellular 2-OG appears to be sequestered in mitochondria and might also be bound by other 2-OG-dependent enzymes 22. Moreover, these 2-OG Km values were determined under idealized conditions with purified enzymes and substrates in the absence of endogenous inhibitors such as reactive oxygen species, nitric oxide, and 2-OG competitive molecules such as succinate and fumarate 1. Studies in model organisms suggest that many metabolic enzymes are saturated in vivo with a mixture of substrate and competitive inhibitors and thus sensitive to changes in substrate concentrations that are far above their nominal Km values 23,24 We confirmed that succinate and fumarate increase the 2-OG requirement for the EglN reaction and that their inhibitory activity, like that of DMOG (Fig 3b) and its active derivative 2-oxalyl glycine, is blunted in the presence of R-2HG (Supplementary Fig 20).

We have not yet formally proven that R-2HG is sufficient to downregulate HIF in intact cells. It is possible, for example, that additional metabolic changes in IDH mutant cells sensitize them to the HIF modulatory effects of R-2HG 25. Another, potentially related, observation is that both downregulation of HIF and transformation by mutant IDH in immortalized human astrocytes, although highly reproducible, was only noted after multiple passages. HIF activates a number of genes, including genes that participate in feedback regulation of the HIF response and genes that modify chromatin structure 1. It is possible that modulation of the HIF response over time, perhaps in conjunction with alterations in other enzymes affected by 2-HG, leads to epigenetic changes that ultimately are responsible for transformation. If so, it will be important to determine the degree to which such changes are reversible.

METHODS

Cell lines

Normal Human Astrocyte (NHA) cell line immortalized with E6/E7/hTERT was described elsewhere 26 and was maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in the presence of 10% CO2 at 37°C. Following retroviral infection, cells were maintained in the presence of hygromycin (100 μg/ml).

Introduction of the IDH1 R132H mutation into HCT116 colon cancer cell lines by homologous recombination was as previously described 27. Briefly, targeting constructs were designed utilizing the pSEPT rAAV shuttle vector 31. Homology arms for the targeting vector were PCR-amplified from HCT116 genomic DNA using Platinum Taq HiFi polymerase (Invitrogen). The R132H hotspot mutation was introduced in the targeting construct using the Quickchange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). An infectious rAAV stock harboring the targeting sequence was generated and applied to parental HCT116 cells as previously described 32, and clones were selected in 0.5 mg/ml geneticin (Invitrogen). Excision of the selectable element was achieved with an adenovirus encoding Cre recombinase (Vector Biolabs). Genomic DNA and total RNA were isolated from cells using QIAmp DNA Blood Kit and RNeasy kit (Qiagen). First strand cDNA was synthesized using iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (BioRad). Successful homologous recombination and cre-mediated excision were verified using PCR-based assays and by direct sequencing of genomic DNA and cDNA.

Anaplastic oligodendroglioma cell lines expressing wild type IDH1 (BT260) or IDH1 R132H (BT237 and BT138) were derived from surgical resection material acquired from patients undergoing surgery at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital on an IRB approved protocol. Briefly, tumor resection samples were mechanically dissociated and tumospheres were established and propagated in Human NeuroCult NS-A Basal media (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with EGF, FGFb, and heparin sulfate. All lines were obtained from the DF/BWCC Living Tissue Bank and confirmed to be derived from recurrent and progressive anaplastic oligodendrogliomas, WHO Grade III, at the time of cell line isolation, and to have chromosome1p/19q codeletion. The presence of IDH R132H mutation was confirmed by mutant specific antibody staining via immunohistochemistry and direct DNA sequencing.

Vectors

Human IDH1 cDNAs (wild-type and R132H) were subcloned as BamHI-EcoRI fragments into pBabe-HA-hygro. Aspartic acid residues 273, 275 and 279 were mutated to asparagines (N) by site-directed mutagenesis and confirmed by DNA sequencing. EglN1, EglN2, and EglN3 cDNAs were subcloned into pLenti6-FLAG expression vector after restriction with XbaI and EcoRI. pLenti6-Flag-EglN1 P317R 33 was prepared by QuikChange Mutagenesis (Stratagene) using pLenti6-Flag EglN1 as a template and the following oligonucleotides: 5’-GTACGTCATGTTGATAATCGAAATGGAGATGGAAGATCTG-3’ and 5’-CACATGTTCCATCTCCATTTCGATTATCAACATGACGTAC-3’. The entire EglN1 coding region was sequenced to verify its authenticity.

Lentiviral (pLKO.1) HIF1α shRNA vectors (TRCN0000003810, target sequence: 5’-GTGATGAAAGAATTACCGAAT-3’; TRCN0000010819, target sequence: 5’-TGCTCTTTGTGGTTGGATCTA-3’; TRCN0000003809, target sequence: 5’-CCAGTTATGATTGTGAAGTTA-3’), EglN1 (PHD2) shRNA vectors (TRCN0000001042, target sequence: 5’-CTGTTATCTAGCTGAGTTCAT-3’; TRCN0000001043, target sequence: 5’-GACGACCTGATACGCCACTGT-3’; TRCN00000010578, target sequence: 5’-TGCACGACACCGGGAAGTTCA-3’), and TET2 shRNA vectors [TRCN0000122172 (122), target sequence: 5’-GCGTTTATCCAGAATTAGCAA-3’; TRCN0000144344 (145), target sequence: 5’-CCTTATAGTCAGACCATGAAA-3’] were obtained from the Broad Institute TRC shRNA library.]. pLKO.1 shRNA with target sequence: 5’-GCAAGCTGACCCTGAAGTTCAT-3’ was used as negative control shRNA.

Immunoblot analysis

Cells extracts were prepared with 1x lysis buffer (50mM Tris [pH 8.0], 120 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete, Roche Applied Science), resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked in TBS with 5% nonfat milk and probed with anti-HIF1α monoclonal antibody (BD Transduction Laboratories), anti-HIF2α polyclonal antibody (NB 100-122, Novus), anti-Flag monoclonal antibody (M2, Sigma-Aldrich), mouse monoclonal anti-HA (HA-11, Covance Research Product), anti-EglN1(PHD2) monoclonal antibody (D31E11, Cell Signaling), anti-GLUT-1 polyclonal antibody (NB300-666, Novus Biologicals), mouse monoclonal anti-tubulin (B-512, Sigma-Aldrich) or anti-vinculin monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). Bound proteins were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Pierce) and Immobilon western chemiluminescent horseradish peroxidase substrate (Millipore).

Liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–mass spectrometry (LC–MS)

Metabolite levels in samples were determined by negative mode electrospray LC–MS as previously described 2. Briefly, metabolites were extracted from exponentially growing cells using 80% aqueous methanol (-80 °C) and were profiled by LC-MS. R-2HG, 2-oxolutarate and succinate were quantified by LC-MS in negative mode using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) on a Quattro micro triple quadruple mass spectrometer (Waters). Samples were diluted with equal amounts of 25% acetonitrile and 10 μl aliquots were analyzed in triplicate. The HPLC column (Luna NH2, 3μm, 2.0 ×100 mm, Phenomenex) was operated isocratically with 130 mM ammonium acetate pH 5.0 in 37% acetonitrile/water. The MRM transitions were: 117>73, 117>93 (succinate), 145>57, 145>101 (2-OG), and 147>85, 147>129 (R-2HG), 0.2 sec dwell time for all transitions. Calibration curves were set up with Quant Lynx, using standards dissolved in reaction buffer.

Enzyme activity assays

R-2HG (H8378) and S-2HG (S765015) were from Sigma. R-2HG was free of contaminating 2-OG as determined by LC-MS under conditions that could detect 0.37 μM exogenous 2-OG in 5 mM R-2HG (data not shown). Human EglN1-3, collagen P4H-I and FIH, and murine Tet1 and Tet2 were produced in insect cells and purified as described earlier 34-37. The plasmids to generate the baculoviruses coding for Tet1 and 2 were a kind gift from Yi Zhang (University of North Carolina). IC50 values for R-2HG and S-2HG were determined based on the hydroxylation-coupled stoichiometric release of 14CO2 from 2-oxo-[1-14C]glutarate using synthetic peptides or double stranded oligonucleotides representing the natural targets of the studied enzymes as substrates. These were DLDLEMLAPYIPMDDDFQL (DLD19) for EglN1-3, (PPG)10 for collagen P4H-I, DESGLPQLTSYDCEVNAPIQGSRNLLQGEELLRAL for FIH and 5’-CTATACCTCCTCAACTT(mC)GATCACCGTCTCCGGCG-3’ for Tet1 and 2. The Ki values for S-2HG for EglN1-3 were determined by adding S-2HG in four constant concentrations while varying the concentration of 2-oxo-[1-14C]glutarate.

In order to study whether R-2HG, which failed to efficiently inhibit EglN activity, could promote EglN activity by acting as a cofactor in the place of 2-OG, we determined the amount of 4-hydroxy[3H]proline formed by a specific radiochemical procedure 38 using a L-[2,3,4,5-3H]proline-labeled HIF-1α oxygen dependent degradation domain (ODDD) as a substrate. Collagen P4H-I and a [14C]-proline-labeled protocollagen 39 substrate were used as controls (detecting 4-hydroxy[14C]proline), and 2-OG (nonlabeled) and S-2HG were assayed for comparison. The Km values of EglN1 and EglN2 were determined by adding increasing amounts of R-2HG while the concentration of the substrate and other cofactors were kept constant.

Generation of a recombinant HIF1α substrate

The HIF1α ODDD substrate, spanning residues 356-603 of human HIF1α, was produced in a BL21(DE3) E. coli strain (Novagen) in the presence of L-[2,3,4,5-3H]proline (75 Ci/mmol, PerkinElmer Life Sciences) and affinity purified in a chelating Sepharose column charged with Ni2+ (ProBond, Invitrogen) exploiting a C-terminal His-tag 40. Concentration of the purified substrate was measured by RotiQuant (Carl Roth GmbH) and it was used at Km concentrations for the distinct EglNs 40.

Modeling

EglN1 active site structure (PDB ID 3HQR, 29) with N-oxalylglycine (NOG, magneta), Mg 2+, and a peptide substrate (light blue), was used to model R-2HG (green) and S-2HG (cyan) into the active site.

Gene expression profiling and gene set enrichment analysis

Expression data from human brain tumor samples were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (http://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/tcgaHome2.jsp) and processed as described 8,28. In short, 200 expression profiles from glioblastoma multiforme and two non-neoplastic brain samples were generated using three platforms (Agilent 244K, Affymetrix HT-HG-U133A, Affymetrix HuEx), preprocessed using gene centric probe sets and three expression values were integrated through factor analysis. After consensus clustering using 1,740 variably expressed genes, profiles with a negative silhouette metric were identified and removed from the data set, leaving expression profiles from 173 GBM tumor samples. IDH1 mutation status was established for 116 out of the 173 samples.

11 gene sets representing response to induced hypoxia were reported in Table S6 from 41. One gene set was from Figure 4C in 9. A final set was assembled by one of us (W.G.K.) based on a literature review of genes upregulated by HIF in a wide variety of cell types (CA9, EglN1, EglN3, SLC2A1, BNIP3, ADM, VEGF, PDK1, LOX, PLOD1, CXCR4, P4HA1, ANKRD37). Single sample GSEA was applied as reported previously 8. Briefly, genes were ranked by their expression values. The empirical cumulative distribution functions (ECDF) of both the genes in the signature as well as the remaining genes were calculated. An enrichment score was obtained by a sum of the difference between a weighted ECDF of the genes in the signature and the ECDF of the remaining genes. This calculation was repeated for all signatures and samples. Z-score transformation was applied to be able to make scores from different gene sets comparable. A positive score indicates gene set activation. A negative value does not indicate inactivation, but rather a lack of effect.

Cell proliferation assays

Cells were plated in 96 well plates (~ 700 cells/well) with a media change every three days. The number of viable cells per well at each time point was measured using an XTT assay (Cell Proliferation Kit II, Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Spectrophotometrical absorbance at 450 nm was measured 5-6 hours after adding the XTT labeling reagent/electron coupling reagent using a microtiter plate reader (Perkin Elmer Life and Analytical Science). For direct cell counting, cells were plated in p60 dishes (~50,000 cells/dish) with a media change every three days. The number of viable cells at each time point was measured after trypan blue staining by using an automated cell counter (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Soft agar colony formation assay

Approximately 8,000 cells were suspended in a top layer of 0.4% soft agar (SeaPlaque Agarose, BMA products) and plated on a bottom layer of 1% soft agar containing complete DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS in 6 well plates. After 3 to 4 weeks, colonies were stained with 0.1% iodonitrotetrazolium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich).

Real-time qPCR analysis

Total RNAs were extracted with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). cDNA synthesis and PCR amplification were performed with Superscript One-Step RT-PCR (Invitrogen) with 2 μg total RNA. EglN3 cDNA was amplified with sense primer (5’-GCGTCTCCAAGCGACA-3’) and antisense primer (5’-GTCTTCAGTGAGGGCAGA-3’). VEGF cDNA was amplified with sense primer 5’-CGAAACCATGAACTTTCTGC-3’) and antisense primer 5’-CCTGAGTGGGCACACACTCC-3’). HIF1α cDNA was amplified with sense primer (5’-TATTGCACTGCACAGGCCACATTC-3’) and antisense primer (5’-TGATGGGTGAGGAATGGGTTCACA-3’). HIF2α was amplified with sense primer (5’-ACAAGCTCCTCTCCTCAGTTTGCT-3’) and antisense primer (5’-ACCCTCCAAGGCTTTCAGGTACAA-3’). GLUT1 CAIX cDNA was amplified with sense primer (5’-TGGAAGAAATCGCTGAGGAAGGCT-3’) and antisense primer (5’-AGCACTCAGCATCACTGTCTGGTT-3’). PDK1 cDNA was amplified with sense primer (5’-ATGATGTCATTCCCACAATGGCCC-3’) and antisense primer (5’-TGAACATTCTGGCTGGTGACAGGA-3’). As a control, β-actin cDNA was amplified with sense primer (5’-ACCAACTGGGACGACATGGAGAAA-3’) and antisense primer (5’-TAGCACAGCCTGGATAGCAACGTA-3’)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Robert P. Hausinger (Michigan State University) and Joshua D. Rabinowitz (Princeton University) for helpful suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript, Drs. Chris Schofield (Oxford University) and Yi Zhang (University of North Carolina) for reagents, Drs. Shuzen Chen and Yang Shi for JMJD2D assays, Dr. Kristian Koski (University of Oulu) for modeling and Tanja Aatsinki and Eeva Lehtimäki for technical assistance. W.G.K. is a Doris Duke Distinguished Clinical Scholar and an HHMI Investigator. Supported by NIH (W.G.K.), HHMI (W.G.K.), Doris Duke Foundation (W.G.K.), Academy of Finland Grants 120156, 140765 and 218129 (P.K.) and S. Juselius Foundation (P.K.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions P.K., S.L. and W.G.K. initiated the project, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. S.L. generated astrocyte cell lines stably expressing various IDH1 proteins. C.G.D., G. Lopez, and H.Y. generated the HCT116 subclones. S.R., K.L.L. and S.W. provided oligodendroglioma cell lines. G. Lu generated and validated the reporter plasmids encoding HIF1α-luciferase fusion proteins. P.J., U.B., S.G. performed the LC-MS analysis. J.T. synthesized 13C-R-2HG and R.L. synthesized and purified different 2-OG and 2-HG derivatives. R.G.W.V. performed the bioinformatics. P.K. and S.L. performed all other experiments with the help of G. Lu, J. A. L. and P.J. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: W.G.K. owns equity in, and consults for, Fibrogen, Inc., which is developing drugs that modulate prolyl hydroxylase activity. S.G. and J.T. are employees of Agios Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Majmundar AJ, Wong WJ, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol Cell. 2010;40:294–309. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dang L, et al. Cancer-associated IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate. Nature. 2009;462:739–744. doi: 10.1038/nature08617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jin G, et al. 2-hydroxyglutarate production, but not dominant negative function, is conferred by glioma-derived NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Figueroa ME, et al. Leukemic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations result in a hypermethylation phenotype, disrupt TET2 function, and impair hematopoietic differentiation. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:553–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu W, et al. Oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chowdhury R, et al. The oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate inhibits histone lysine demethylases. EMBO Rep. 2011 doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruning U, et al. MicroRNA-155 Promotes Resolution of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1{alpha} Activity During Prolonged Hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1128/MCB.01276-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verhaak RG, et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nickols NG, Jacobs CS, Farkas ME, Dervan PB. Modulating hypoxia-inducible transcription by disrupting the HIF-1-DNA interface. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2:561–571. doi: 10.1021/cb700110z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aghili M, Zahedi F, Rafiee E. Hydroxyglutaric aciduria and malignant brain tumor: a case report and literature review. J Neurooncol. 2009;91:233–236. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9706-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moroni I, et al. L-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria and brain malignant tumors: a predisposing condition? Neurology. 2004;62:1882–1884. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000125335.21381.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozisik PA, Akalan N, Palaoglu S, Topcu M. Medulloblastoma in a child with the metabolic disease L-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2002;37:22–26. doi: 10.1159/000065097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao S, et al. Glioma-derived mutations in IDH1 dominantly inhibit IDH1 catalytic activity and induce HIF-1alpha. Science. 2009;324:261–265. doi: 10.1126/science.1170944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams SC, et al. R132H-mutation of isocitrate dehydrogenase-1 is not sufficient for HIF-1alpha upregulation in adult glioma. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:279–281. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0790-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carmeliet P, et al. Role of HIF-1alpha in hypoxia-mediated apoptosis, cell proliferation and tumour angiogenesis. Nature. 1998;394:485–490. doi: 10.1038/28867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mack FA, et al. Loss of pVHL is sufficient to cause HIF dysregulation in primary cells but does not promote tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:75–88. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00240-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song LP, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha-induced differentiation of myeloid leukemic cells is its transcriptional activity independent. Oncogene. 2008;27:519–527. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Acker T, et al. Genetic evidence for a tumor suppressor role of HIF-2alpha. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blouw B, et al. The hypoxic response of tumors is dependent on their microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:133–146. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christensen BC, et al. DNA methylation, isocitrate dehydrogenase mutation, and survival in glioma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:143–153. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koivunen P, et al. Inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) hydroxylases by citric acid cycle intermediates: possible links between cell metabolism and stabilization of HIF. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4524–4532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610415200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pritchard JB. Intracellular alpha-ketoglutarate controls the efficacy of renal organic anion transport. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;274:1278–1284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett BD, et al. Absolute metabolite concentrations and implied enzyme active site occupancy in Escherichia coli. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:593–599. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuan J, et al. Metabolomics-driven quantitative analysis of ammonia assimilation in E. coli. Mol Syst Biol. 2009;5:302. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reitman ZJ, et al. Profiling the effects of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 mutations on the cellular metabolome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3270–3275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019393108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sonoda Y, et al. Formation of intracranial tumors by genetically modified human astrocytes defines four pathways critical in the development of human anaplastic astrocytoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4956–4960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rago C, Vogelstein B, Bunz F. Genetic knockouts and knockins in human somatic cells. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2734–2746. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang XV, Verhaak RG, Purdom E, Spellman PT, Speed TP. Unifying gene expression measures from multiple platforms using factor analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chowdhury R, et al. Structural basis for binding of hypoxia-inducible factor to the oxygen-sensing prolyl hydroxylases. Structure. 2009;17:981–989. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koski MK, et al. The active site of an algal prolyl 4-hydroxylase has a large structural plasticity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37112–37123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706554200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Topaloglu O, Hurley PJ, Yildirim O, Civin CI, Bunz F. Improved methods for the generation of human gene knockout and knockin cell lines. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kohli M, Rago C, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Facile methods for generating human somatic cell gene knockouts using recombinant adeno-associated viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e3. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Percy MJ, et al. A family with erythrocytosis establishes a role for prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2 in oxygen homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:654–659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508423103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirsila M, et al. Effect of desferrioxamine and metals on the hydroxylases in the oxygen sensing pathway. FASEB J. 2005;19:1308–1310. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3399fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koivunen P, Hirsila M, Gunzler V, Kivirikko KI, Myllyharju J. Catalytic properties of the asparaginyl hydroxylase (FIH) in the oxygen sensing pathway are distinct from those of its prolyl 4-hydroxylases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9899–9904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312254200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ito S, et al. Role of Tet proteins in 5mC to 5hmC conversion, ES-cell self-renewal and inner cell mass specification. Nature. 2010;466:1129–1133. doi: 10.1038/nature09303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Annunen P, et al. Cloning of the human prolyl 4-hydroxylase alpha subunit isoform alpha(II) and characterization of the type II enzyme tetramer. The alpha(I) and alpha(II) subunits do not form a mixed alpha(I)alpha(II)beta2 tetramer. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17342–17348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Juva K, Prockop DJ. Modified procedure for the assay of H-3-or C-14-labeled hydroxyproline. Anal Biochem. 1966;15:77–83. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(66)90249-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kivirikko KI, Myllyla R. Posttranslational enzymes in the biosynthesis of collagen: intracellular enzymes. Methods Enzymol. 1982;82(Pt A):245–304. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(82)82067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koivunen P, Hirsila M, Kivirikko KI, Myllyharju J. The length of peptide substrates has a marked effect on hydroxylation by the hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl 4-hydroxylases. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:28712–28720. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604628200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benita Y, et al. An integrative genomics approach identifies Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1 (HIF-1)-target genes that form the core response to hypoxia. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4587–4602. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.