Abstract

The aim of this study was to develop a brief informant-based questionnaire, namely the Symptoms of Early Dementia-11 Questionnaire (SED-11Q), for the screening of early dementia. 459 elderly individuals participated, including 39 with mild cognitive impairment in the Clinical Dementia Rating scale (CDR) 0.5, 233 with mild dementia in CDR 1, 106 with moderate dementia in CDR 2, and 81 normal controls in CDR 0. Informants were required to fill out a 13-item questionnaire. Two items were excluded after analyzing sensitivities and specificities. The final version of the SED-11Q assesses memory, daily functioning, social communication, and personality changes. Receiver operator characteristic curves assessed the utility to discriminate between CDR 0 (no dementia) and CDR 1 (mild dementia). The statistically optimal cutoff value of 2/3, which indicated a sensitivity of 0.84 and a specificity of 0.90, can be applied in the clinical setting. In the community setting, a cutoff value of 3/4, which indicated a sensitivity of 0.76 and a specificity of 0.96, is recommended to avoid false positives. The SED-11Q reliably differentiated nondemented from demented individuals when completed by an informant, and thus is practical as a rapid screening tool in general practice, as well as in the community setting, to decide whether to seek further diagnostic confirmation.

Key Words : Dementia screening, Dementia, Alzheimer's disease, Activities of daily living, Cognitive deficits, Early detection, Mild cognitive impairment, Non-Alzheimer's disease

Introduction

There is widespread underascertainment of Alzheimer's disease (AD) and other dementias [1], and a combination of pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments could slow disease progression and maintain individuals at their highest level of functioning when they are at the early stages of disease [2]. For early detection of dementia, a rapid screening test in clinical settings would be extremely useful, as it could help general practitioners with time constraints to decide whether or not to proceed with more in-depth clinical evaluation. Such a screening test is also useful for community health promotion to detect undiagnosed individuals.

An ideal practical screening test should be easy to administer within tight time constraints but must also be accurate enough to detect dementia. There are two general methods to screen for dementia: patient performance-based testing and informant interviews.

Regarding patient performance-based testing, the most widely used brief test is the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [3]. However, this test is time-consuming to administer in a clinical setting with time constraints. Furthermore, the ceiling effect makes the MMSE insensitive to the early stages of dementia [4], especially for highly educated individuals [5,6]. In contrast, a brief test such as the MMSE may falsely identify those with low education or poor cognitive functioning as demented. Other brief tests have also been developed. However, because of the requirement of brevity, most of them are limited to a single cognitive domain. For instance, the tests that are weighted towards memory such as the Short Blessed Test [7] and the Memory Impairment Screen [8] may not be sensitive enough for detecting nonamnestic dementias. Another problem is the psychological burden imposed by cognitive tests, as cognitive tests for dementia are themselves stressful [1].

In the community-based setting, performance-based tests may be impractical for detecting underdiagnosed dementia. A lack of self-awareness of cognitive decline is a characteristic of dementia [9,10], and demented individuals tend to deny their cognitive decline and refuse the test. Ethical issues are also important; using screening tests with low specificity could lead to a misdiagnosis of dementia in elderly individuals, which could cause unnecessary anxiety. The detection of dementia should be conducted without unduly alarming the patient. In this respect, informant-based assessments are preferable.

When evaluating informant-based assessments, the Clinical Dementia Rating scale (CDR) [11] is widely used. CDR meets the requirement of accuracy, but it is not an easily administered screening tool. It is a semistructured interview that has to be carried out by trained practitioners and takes at least 30 min.

In the present study, we introduce a brief informant-based screening questionnaire to identify dementia in both clinical and community-based settings, namely the Symptoms of Early Dementia-11 Questionnaire (SED-11Q). This questionnaire is easily administered and is both patient and informant friendly. Questions addressing early signs of dementia were selected on the basis of clinical experience. The SED-11Q aims to investigate the state of ordinary daily activities often performed by an elderly individual living independently. The questions it asks are not only easy to answer, but are also informative. Quantifying difficulties in daily living may provide more sensitive information about early functional changes rather than questions about cognitive function in a single domain. This is because functional integrity is a key differentiating feature of dementia, and a decline in multifaceted cognitive domains directly leads to functional impairments. In addition, as deficits caused by dementia are manifested in various aspects, the SED-11Q also includes questions on social interaction and personality.

Methods

459 elderly individuals participated, including 39 with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in CDR 0.5, 233 with mild dementia in CDR 1, 106 with moderate dementia in CDR 2, and 81 normal controls in CDR 0. The demented individuals were outpatients, and of the 81 normal controls, 64 were community dwellers and 17 were outpatients (table 1). The subjects were diagnosed based on criteria for dementia diseases such as NINCDS-ADRDA for AD [12], the third report of the Dementia with Lewy Bodies Consortium for Lewy body dementia [13], criteria by Neary et al. [14] for frontotemporal lobar degeneration, criteria by the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop for vascular dementia [15], and MCI by the report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment [16]. CDR 0.5 was regarded as MCI, although a different classification was proposed, whereby CDR 0.5 encompasses both mild and earlier dementia [17] or it corresponds to very mild dementia [18]. Depression was an exclusive criterion for normal controls in CDR 0 and subjects with MCI in CDR 0.5. The ethics board of the Gunma University School of Health Sciences approved all procedures (No. 21-27), and written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Table 1.

Demographic data

| CDR 0 (n = 81) | CDR 0.5 (n = 39) | CDR 1 (n = 233) | CDR 2 (n = 106) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 71.7 ± 6.0 | 78.7 ± 6.9 | 79.6 ± 9.7 | 79.5 ± 13.2 |

| Gender (male/female) | 74/7 | 18/21 | 82/151 | 29/77 |

| MMSE | 28.5 ± 2.1 | 26.4 ± 2.2 | 21.1 ± 4.2 | 16.1 ± 4.2 |

| SED-11Q | 1.00 ± 1.29 | 3.21 ± 2.14 | 5.71 ± 2.78 | 7.25 ± 2.88 |

| Causative diseases | ||||

| AD | 5.76 ± 2.76 (127) | 6.95 ± 2.79 (40) | ||

| Others | 5.66 ± 2.81 (106) | 7.44 ± 2.93 (66) |

With the exception of gender (number of patients) values represent mean ± SD. Values in parentheses represent the number of patients. The ages were significantly different between the groups (p < 0.001). CDR 0 was detected significantly more frequently in the younger groups. There was no difference between the affected groups of CDR 0.5, CDR 1, and CDR 2.

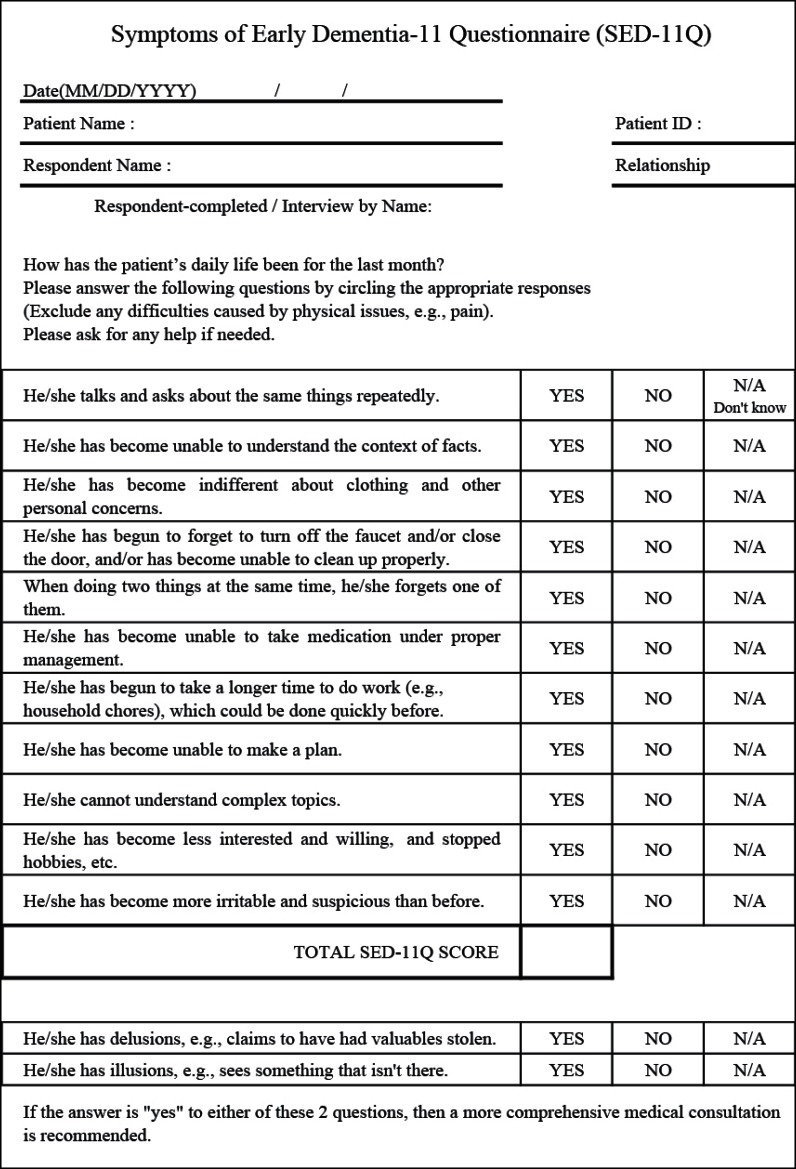

Originally, the questionnaire consisted of 13 questions, which are shown in table 2. In the clinical and community setting, the informants were required to fill out the questionnaire including the 13 items. Based on the results of the current study, we decided to exclude 2 items: item 2 (misplacing) and item 13 (delusions). The format of the SED-11Q is shown in figure 1. In the present study, informants were limited to family members, and nonfamily caregivers were excluded. Informants had normal cognitive abilities without psychiatric diseases, delirium, or verbal incomprehension including aphasia.

Table 2.

Sensitivity and specificity of the 13 subitems in the differentiation between CDR 0 and CDR 1

| Item | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Repetitive talking | 0.81 | 0.79 |

| 2 | Misplacing | 0.85 | 0.49 |

| 3 | Context understanding | 0.52 | 0.99 |

| 4 | Indifference about clothing | 0.31 | 0.91 |

| 5 | Cleaning up | 0.35 | 0.91 |

| 6 | Forgetting one of two items | 0.60 | 0.90 |

| 7 | Self-medication | 0.47 | 1.00 |

| 8 | Time consuming | 0.62 | 0.88 |

| 9 | Planning | 0.52 | 0.98 |

| 10 | Complex topics | 0.64 | 0.93 |

| 11 | Loss of interest | 0.54 | 0.93 |

| 12 | Irritable and suspicious | 0.33 | 0.81 |

| 13 | Delusions | 0.18 | 1.00 |

Fig. 1.

Format of the SED-11Q. The questionnaire represents an informant-based screening and should not be used as a patient-completed screening questionnaire. The total SED-11Q score is the sum of the items marked ‘Yes’.

The patients were also tested using the MMSE. All analyses were conducted using the Japanese version of SPSS for Windows version 19.0 (IBM Corp., New York, N.Y., USA). Significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

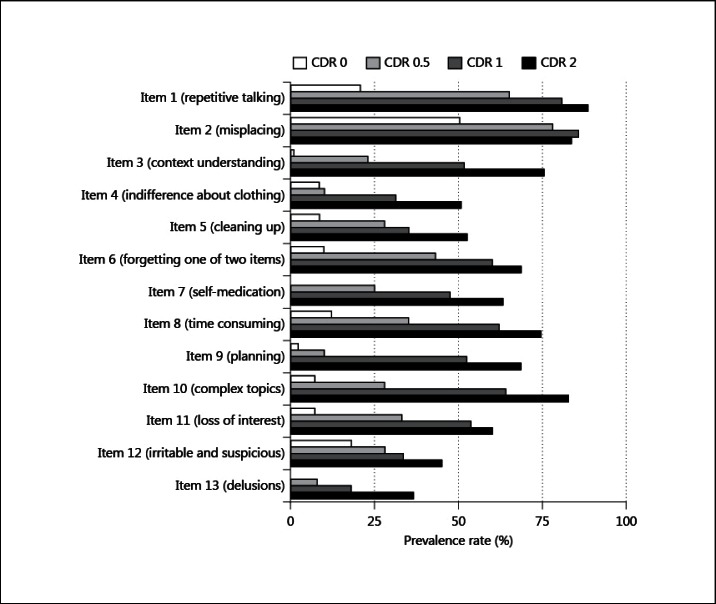

Demographic data are shown in table 1. The ratio of positive answers in subitems in the quotient is shown in figure 2. In CDR 0, 51% checked item 2, whereas no one checked items 7 and 13. In CDR 1, more than 50% checked items 1, 2, 3, 6, 8, 9, 10, and 11. Sensitivities and specificities of the subitems in CDR 0 and CDR 1 are shown in table 2. Item 2 (misplacing) showed the lowest specificity, i.e. 0.49, out of the 13 items. Item 13 (delusions) showed the lowest sensitivity, i.e. 0.18, although the specificity was 1. Therefore, these 2 items were removed in the SED-11Q. Instead, a notification was added to recommend medical consultation whenever delusions or illusions were detected.

Fig. 2.

The ratio of positive answers in the subitems (quotients) according to the CDR groups.

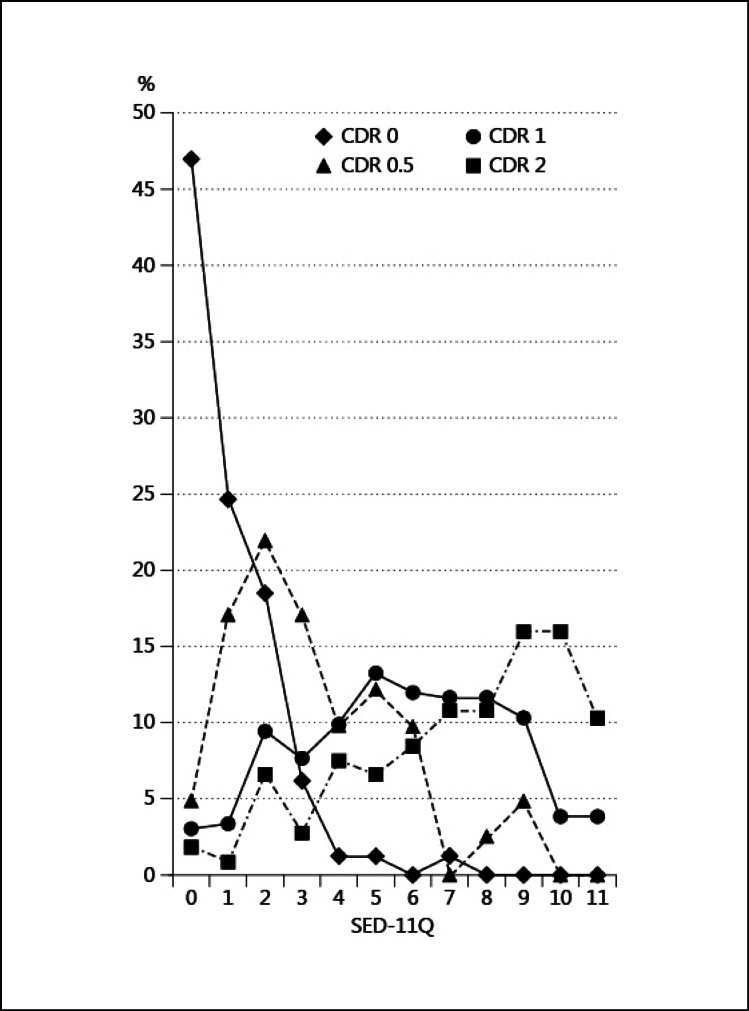

Scores were as follows: 1.00 ± 1.29 (mean ± SD) in CDR 0, 3.21 ± 2.14 in CDR 0.5, 5.71 ± 2.78 in CDR 1, and 7.25 ± 2.88 in CDR 2. There was a significant difference among the CDR groups [analysis of variance F(3, 455) = 106.264, p < 0.001], and post hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction indicated the following significant differences: CDR 2 higher than CDR 1, CDR 1 higher than CDR 0.5, and CDR 0.5 higher than CDR 0 (p < 0.001). Modes of the scores were 0 in CDR 0, 2 in CDR 0.5, 5 in CDR 1, and 9/10 in CDR 2 (fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Distribution according to the severity of dementia. The distribution is shown in the quotients. Modes of scores were 0 in CDR 0, 1 in CDR 0.5, 5 in CDR 1, and 9/10 in CDR 2.

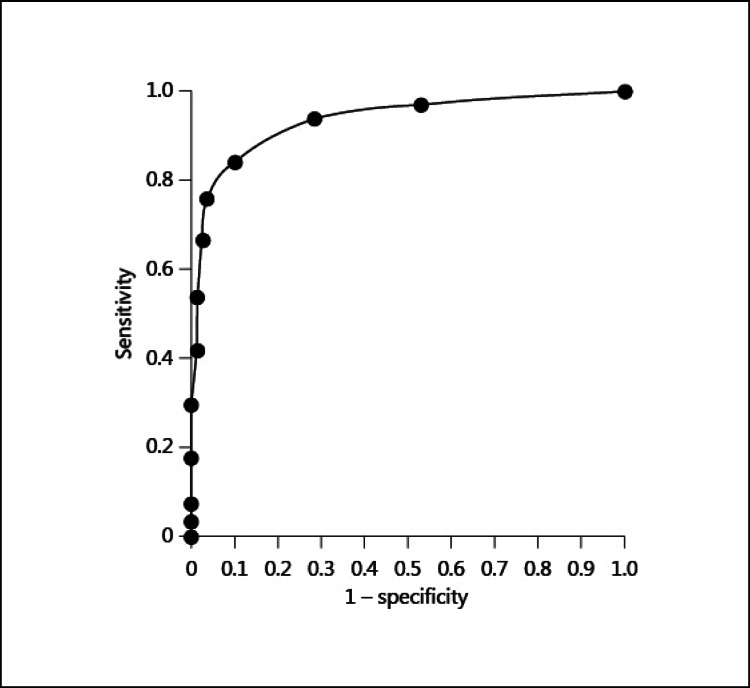

Comparing CDR 0 and CDR 1 in the SED-11Q, the area under receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was 0.932 [p < 0.001, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.903-0.961]. A cutoff value of 2/3 indicated a sensitivity of 0.841 (95% CI: 0.817-0.857), a specificity of 0.901 (95% CI: 0.830-0.947), a positive predictive value of 0.961 (95% CI: 0.933-0.979), and a negative predictive value of 0.664 (95% CI: 0.611-0.697). A cutoff value of 3/4 indicated a sensitivity of 0.764 (95% CI: 0.743-0.772), a specificity of 0.963 (95% CI: 0.903-0.987), a positive predictive value of 0.983 (95% CI: 0.957-0.994), and a negative predictive value of 0.586 (95% CI: 0.550-0.601) (fig. 4). The correlation coefficient of the SED-11Q and the MMSE was significant: r = −0.424 and r < 0.001.

Fig. 4.

The ROC curve of the SED-11Q in the differentiation between CDR 0 and CDR 1. The area under the curve is 0.932 (p < 0.001, 95% CI: 0.903-0.961). The statistically optimal cutoff value of 2/3 indicated a sensitivity of 0.841 and a specificity of 0.901.

Discussion

The SED-11Q reliably differentiated nondemented from demented individuals. The area under the ROC curve was 93%, suggesting good discrimination between the 2 groups. In the clinical setting with physicians and other medical staff, the statistically optimal cutoff value of 2/3, which indicates a sensitivity of 0.841 and a specificity of 0.901, can be applied. In the community setting, where community-dwelling elderly individuals are screened for detecting dementia, a cutoff value of 3/4, which indicates a sensitivity of 0.764 and a specificity of 0.963, is recommended because of high specificity and positive predictive values. Medical consultation is recommended whenever delusions or illusions are detected. In general, the SED-11Q was revealed to be practical as a rapid screening tool in general practice to decide whether or not to seek further diagnostic confirmation.

Consideration of Subitems

The 2 items that assessed memory function, item 1 (repetitive talking) and item 2 (misplacing), showed high sensitivities of 0.8 and more comparing CDR 0 to CDR 1. Amnestic disorder is one of the earliest signs of AD, and the reason for this could be the fact that the majority of the patients were those with AD in the present study. Item 2 (misplacing) was excluded from the SED-11Q because the specificity was 0.49, which suggested a danger of false positivity.

In CDR 1, deficits in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) become obvious. In the present study, 4 items, item 3 (context understanding), item 6 (forgetting one of two items), item 8 (time-consuming), and item 9 (planning), showed sensitivities of 0.5 and more and specificities of 0.85 and more in the comparison between CDR 0 and CDR 1. It becomes difficult for the patients in CDR 1 to function independently, even if compensatory strategies are employed, and deficits can be noticed in cooperative activities and conversations in daily living.

The other 2 items regarding IADL, item 4 (indifference about clothing) and item 5 (cleaning up), showed sensitivities of less than 0.5, while specificities were 0.9 and more in the comparison between CDR 0 and CDR 1. It is possible that informants tend to pay little attention and overlook the deficits because of slow and gradual changes. These items remained in the list, considering a community-based use, as it could help elderly individuals if symptoms of dementia other than memory deficits are detected by using the questionnaire. Item 4 (indifference about clothing) could gradually lead to an apathetic attitude to life, which is one of the psychological behavioral symptoms of dementia and aggravates cognitive function. Item 5 (cleaning up) is a typical behavior of demented individuals with attentional deficits and difficulties in executive function.

A relatively low sensitivity of 0.47 in item 7 (self-medication) is rather unexpected, because previous studies suggested that self-medication is one of the early signs of dementia [19,20,21,22,23,24]. Possible causes for this discrepancy could be that some patients may have developed long-term habits of medication, e.g., antihypertensive drugs, while others may not have taken any medications, as the questionnaire was filled out at the initial visit. A specificity of 100% suggested that self-medication could be a robust sign of dementia, and follow-up is needed to observe whether those already affected by dementia can acquire a habit of self-medication or not.

For item 10 (complex topics), cognitive decline is associated with difficulties in social interaction. Socially active lifestyles have a protective influence on mental decline: social isolation is associated with an increased risk of mental decline [25,26], whereas a rich social network and interaction may protect against mental decline [27,28]. It becomes difficult for patients to maintain socially active lives, and thus it is desirable that families and caregivers help the patients keep up social interaction.

Changes in interests are also characteristic of the early stages of dementia, as assessed by item 11 (loss of interest) in this questionnaire. Due to cognitive decline, patients are confronted with the loss of mental capacity. They have difficulty in doing what they could easily do and have enjoyed doing previously. Consequently, they lose their motivation and tend to be apathetic. Item 11 (loss of interest) is also related to social interaction; it becomes difficult to maintain social interaction even with those sharing the same hobbies. Families and caregivers should watch for changes because apathy and inaction are related to increased functional disability [29].

Personal changes are also observed in individuals with dementias other than AD, and the SED-11Q aims to detect these dementias. Item 12 asks about changes relating to irritability and suspicion, which are observed in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and are early signs of disease. Items 4 and 11 are associated with apathetic changes, which are more prominent in vascular dementia than in AD [30]. These 2 items could lead to depressive tendencies, which is a frequent symptom of Lewy body dementia [31].

Concerning item 13 (delusions), sensitivity was low, whereas specificity was 100%. Thus, it could be regarded as a determining factor in the diagnosis of dementia or other psychiatric diseases. In the SED-11Q, item 13 was excluded and notification was added to recommend medical consultation whenever delusions or illusions are detected.

Discriminative Ability of the SED-11Q

In the clinical setting, a statistically optimal cutoff value of 2/3 can be applied, whereas in the community setting, a cutoff value of 3/4 is recommended (fig. 4). In the clinical setting, medical staff can determine whether the informants are reliable or not, and they can interview the informants and patients if necessary, whereas in the community setting, such screening is often conducted without medical staff.

In general, during screening, false positives may be preferable to false negatives because failure of early detection could result in a lack of early intervention. However, considering the characteristics of dementia, false negatives are preferable in brief screening. Disease-modifying drugs have not been developed and cognitive and functional capacity would inevitably decline as the disease progresses. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) warned that labeling an individual with dementia could potentially cause unnecessary anxiety, which is a risk factor for cognitive decline [32]. Therefore, physicians should perform a careful examination to make a definitive diagnosis, but cognitive tests for dementia are inherently potentially stressful. In this way, not only an incorrect diagnosis of dementia, but also the notification of the probability of dementia could lead to negative psychosocial consequences. Thus, it makes sense to value specificity more than sensitivity, especially in community settings.

The SED-11Q should not be used to detect MCI (CDR 0.5), as the screening of asymptomatic stages should be conducted carefully. The results of the present study showed a wide distribution of scores in CDR 0.5, and considering the negative psychosocial consequences which result from a false-positive judgment, a diagnosis of MCI should be carefully made.

Self-Rating Scales

Self-rating scales are not appropriate to detect dementia, because subjective cognitive impairment and memory complaints are common in elderly individuals [33,34,35,36]. It is controversial whether subjective complaints are associated with cognitive decline [37,38], and it has been reported that such complaints are correlated with depressive symptoms or personality traits, rather than cognitive decline [39,40]. In addition, those who are already demented tend to overestimate their functions, and their self-awareness of cognitive impairments diminishes as disease progresses, especially in memory [9,10].

Other Informant-Based Questionnaires

Other informant-based questionnaires have been developed. In 1989, the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE; available in 26- and 16-item formats) [41] was proposed. It requires an intrapersonal comparison between the present states and those of 10 years ago. However, memories of 10 years ago are vague, and normally aging individuals experience cognitive declines. Thus, the IQCODE can result in false-positive diagnoses, and age-related changes are often misdiagnosed as symptoms of dementia. Furthermore, the IQCODE includes questions on symptoms associated with rather advanced stages, e.g., not recognizing the faces of family members, not remembering the names of family members, not remembering things that happened to him/her when he/she was young, and not remembering things he/she learned when he/she was young.

Another example is the Observation List of Possible Early Signs of Dementia (OLD) [42]. This test focuses on cognitive decline, and questions about daily functioning are not included. Combined questionnaires that ask about cognitive function and daily functioning are desirable [43], as daily functioning requires multifaceted cognitive abilities, and deficits in functional integrity represent a key feature of dementia.

A brief scale combining a single-item informant report of memory problems and a 4-item IADL scale has also been proposed [44]. Although the test itself is easy and brief, the scoring system is complicated and arbitrary, and the test has not been validated with a large cohort.

Another scale that combines questions on cognitive abilities and daily functioning is the 8-item questionnaire, AD8 [43]. AD8 consists of questions about the patient's memory, orientation, and functional abilities by placing emphasis on intraindividual, rather than interindividual comparisons. However, the time frame for change is set as the last several years (an exact time frame is not required). Most of the informants whom we meet in daily practice tend to overlook longitudinal change. It would be more practical to ask about the patient's state during a short period, such as the last month. The validity and reliability were confirmed in early dementia; a score of 2 or more points suggested that cognitive impairment is likely present with a sensitivity over 84% and a specificity over 80%. The negative predictive value was around 70%, and thus there is a risk of overdiagnosis. AD8 was also recommended for detection of MCI, but screening of MCI using such brief tests could result in unnecessary false-positive judgment, as stated above. In the absence of informants, the authors recommend AD8 as a self-completion questionnaire, as they reported that self-rating of AD8 differentiated nondemented from demented individuals with the same specificity as informant ratings [45]. However, the results have not been validated in other cohorts. As stated above in the ‘Self-rating scales’ section, it is debatable whether self-ratings should be considered as reliable as informants’ reports.

Limitations

Reliable informants are not always available. In cases with no reliable informants, a detailed medical interview and examination should be conducted. It is inadvisable to rely on data derived from the SED-11Q when it has been used for self-rating for the reasons stated above. Moreover, it should be noted that scores can be biased by informant depression, care burden, and the relationship with the patient. False positivity is possible for those with depression, as depression, even without comorbid dementia, causes cognitive deficits. It might be necessary to rule out depression at the initial screening using the SED-11Q. Differentiation of dementia from depression requires careful examination, and depression itself is an important risk factor for dementia [46,47,48]. Another limitation is that this study included few cases of dementias other than AD, and samples should be collected to confirm the reliability of this test in other dementias.

The questionnaire should be validated in a multisite study in both practical and community settings.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the study participants, Dr. Masamitsu Takatama (Geriatrics Research Institute and Hospital, Maebashi), and Rumi Shinohara and Yuko Tsunoda (Gunma University, Maebashi) for their support. Dr. Haruyasu Yamaguchi was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, Culture, and Technology, Japan (23300197 and 22650123) and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (H22-Ninchisho-Ippan-004) from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japan.

References

- 1.Holsinger T, Deveau J, Boustani M, Williams JW., Jr Does this patient have dementia? JAMA. 2007;297:2391–2404. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.21.2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boustani M, Peterson B, Hanson L, Harris R, Lohr KN. Screening for dementia in primary care: a summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:927–937. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-11-200306030-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state'. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence J, Davidoff D, Katt-Lloyd D, Auerbach M, Hennen J. A pilot program of improved methods for community-based screening for dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9:205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Espino DV, Lichtenstein MJ, Palmer RF, Hazuda HP. Evaluation of the mini-mental state examination's internal consistency in a community-based sample of Mexican-American and European-American elders: results from the San Antonio Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:822–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lorentz WJ, Scanlan JM, Borson S. Brief screening tests for dementia. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47:723–733. doi: 10.1177/070674370204700803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H. Validation of a short Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:734–739. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuslansky G, Buschke H, Katz M, Sliwinski M, Lipton RB. Screening for Alzheimer's disease: the memory impairment screen versus the conventional three-word memory test. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1086–1091. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mograbi DC, Brown RG, Morris RG. Anosognosia in Alzheimer's disease – the petrified self. Conscious Cogn. 2009;18:989–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maki Y, Amari M, Yamaguchi T, Nakaaki S, Yamaguchi H. Anosognosia: patients' distress and self-awareness of deficits in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27:339–345. doi: 10.1177/1533317512452039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Dekosky ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Cummings J, Delacourte A, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Jicha G, Meguro K, O'Brien J, Pasquier F, Robert P, Rossor M, Salloway S, Stern Y, Visser PJ, Scheltens P. Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:734–746. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O'Brien JT, Feldman H, Cummings J, Duda JE, Lippa C, Perry EK, Aarsland D, Arai H, Ballard CG, Boeve B, Burn DJ, Costa D, Del Ser T, Dubois B, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Goetz CG, Gomez-Tortosa E, Halliday G, Hansen LA, Hardy J, Iwatsubo T, Kalaria RN, Kaufer D, Kenny RA, Korczyn A, Kosaka K, Lee VM, Lees A, Litvan I, Londos E, Lopez OL, Minoshima S, Mizuno Y, Molina JA, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, Pasquier F, Perry RH, Schulz JB, Trojanowski JQ, Yamada M, Consortium on DLB. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65:1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, Passant U, Stuss D, Black S, Freedman M, Kertesz A, Robert PH, Albert M, Boone K, Miller BL, Cummings J, Benson DF. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51:1546–1554. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Román GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, Cummings JL, Masdeu JC, Garcia JH, Amaducci L, Orgogozo JM, Brun A, Hofman A, et al. Vascular dementia: diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop. Neurology. 1993;43:250–260. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reisberg B, Ferris SH, Kluger A, Franssen E, Wegiel J, de Leon MJ. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI): a historical perspective. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20:18–31. doi: 10.1017/S1041610207006394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grundman M, Petersen RC, Ferris SH, Thomas RG, Aisen PS, Bennett DA, Foster NL, Jack CR, Jr, Galasko DR, Doody R, Kaye J, Sano M, Mohs R, Gauthier S, Kim HT, Jin S, Schultz AN, Schafer K, Mulnard R, van Dyck CH, Mintzer J, Zamrini EY, Cahn-Weiner D, Thal LJ, Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study Mild cognitive impairment can be distinguished from Alzheimer disease and normal aging for clinical trials. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:59–66. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund LO, Nordberg A, Bäckman L, Albert M, Almkvist O, Arai H, Basun H, Blennow K, de Leon M, DeCarli C, Erkinjuntti T, Giacobini E, Graff C, Hardy J, Jack C, Jorm A, Ritchie K, van Duijn C, Visser P, Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment – beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med. 2004;256:240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barberger-Gateau P, Dartigues JF, Letenneur L. Four Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Score as a predictor of one-year incident dementia. Age Ageing. 1993;22:457–463. doi: 10.1093/ageing/22.6.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edelberg HK, Shallenberger E, Wei JY. Medication management capacity in highly functioning community-living older adults: detection of early deficits. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:592–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb02574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edelberg HK, Shallenberger E, Hausdorff JM, Wei JY. One-year follow-up of medication management capacity in highly functioning older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M550–M553. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.10.m550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutchison LC, Jones SK, West DS, Wei JY. Assessment of medication management by community-living elderly persons with two standardized assessment tools: a cross-sectional study. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lieto JM, Schmidt KS. Reduced ability to self-administer medication is associated with assisted living placement in a continuing care retirement community. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2005;6:246–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt KS, Lieto JM. Validity of the Medication Administration Test among older adults with and without dementia. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2005;3:255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bassuk SS, Glass TA, Berkman LF. Social disengagement and incident cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly persons. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:165–173. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-3-199908030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson RS, Krueger KR, Arnold SE, Schneider JA, Kelly JF, Barnes LL, Tang Y, Bennett DA. Loneliness and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:234–240. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fratiglioni L, Wang HX, Ericsson K, Maytan M, Winblad B. Influence of social network on occurrence of dementia: a community-based longitudinal study. Lancet. 2000;355:1315–1319. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang HX, Karp A, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Late-life engagement in social and leisure activities is associated with a decreased risk of dementia: a longitudinal study from the Kungsholmen project. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:1081–1087. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.12.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vilalta-Franch J, Calvo-Perxas L, Garre-Olmo J, Turro-Garriga O, Lopez-Pousa S. Apathy syndrome in Alzheimer's disease epidemiology: prevalence, incidence, persistence, and risk and mortality factors. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33:535–543. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D'Onofrio G, Sancarlo D, Panza F, Copetti M, Cascavilla L, Paris F, Seripa D, Matera MG, Solfrizzi V, Pellegrini F, Pilotto A. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and functional status in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia patients. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:759–771. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weisman D, McKeith I. Dementia with Lewy bodies. Semin Neurol. 2007;27:42–47. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-956754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Middleton LE, Yaffe K. Promising strategies for the prevention of dementia. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1210–1215. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bassett SS, Folstein MF. Memory complaint, memory performance, and psychiatric diagnosis: a community study. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1993;6:105–111. doi: 10.1177/089198879300600207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tobiansky R, Blizard R, Livingston G, Mann A. The Gospel Oak Study stage IV: the clinical relevance of subjective memory impairment in older people. Psychol Med. 1995;25:779–786. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jonker C, Geerlings MI, Schmand B. Are memory complaints predictive for dementia? A review of clinical and population-based studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:983–991. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200011)15:11<983::aid-gps238>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riedel-Heller SG, Matschinger H, Schork A, Angermeyer MC. Do memory complaints indicate the presence of cognitive impairment? Results of a field study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;249:197–204. doi: 10.1007/s004060050087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geerlings MI, Jonker C, Bouter LM, Ader HJ, Schmand B. Association between memory complaints and incident Alzheimer's disease in elderly people with normal baseline cognition. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:531–537. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.St John P, Montgomery P. Is subjective memory loss correlated with MMSE scores or dementia? J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2003;16:80–83. doi: 10.1177/0891988703016002003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carr DB, Gray S, Baty J, Morris JC. The value of informant versus individual's complaints of memory impairment in early dementia. Neurology. 2000;55:1724–1726. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.11.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pearman A, Storandt M. Predictors of subjective memory in older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004;59:4–6. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.1.p4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jorm AF, Jacomb PA. The Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): socio-demographic correlates, reliability, validity and some norms. Psychol Med. 1989;19:1015–1022. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700005742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hopman-Rock M, Tak EC, Staats PG. Development and validation of the Observation List for early signs of Dementia (OLD) Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:406–414. doi: 10.1002/gps.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galvin JE, Roe CM, Powlishta KK, Coats MA, Muich SJ, Grant E, Miller JP, Storandt M, Morris JC. The AD8: a brief informant interview to detect dementia. Neurology. 2005;65:559–564. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172958.95282.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li M, Ng TP, Kua EH, Ko SM. Brief informant screening test for mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;21:392–402. doi: 10.1159/000092808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galvin JE, Roe CM, Coats MA, Morris JC. Patient's rating of cognitive ability: using the AD8, a brief informant interview, as a self-rating tool to detect dementia. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:725–730. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rapp MA, Dahlman K, Sano M, Grossman HT, Haroutunian V, Gorman JM. Neuropsychological differences between late-onset and recurrent geriatric major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:691–698. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baune BT, Suslow T, Arolt V, Berger K. The relationship between psychological dimensions of depressive symptoms and cognitive functioning in the elderly – the MEMO-Study. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Porter RJ, Gallagher P, Thompson JM, Young AH. Neurocognitive impairment in drug-free patients with major depressive disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:214–220. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.3.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]