Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) is a known cause of secondary pneumothorax. In areas with endemic TB, complications from the disease, including pneumothorax, are increasing in prevalence. We present the cases of 3 patients (ages 32 years, 17 years, and 3 months) seen in the emergency department at John F. Kennedy Medical Center in Monrovia, Liberia, West Africa. Each presented with shortness of breath and cough, and with some degree of respiratory distress. Airway compromise was present with tracheal or mediastinal deviation. Each patient underwent tube thoracostomy with improvement in pneumothorax and respiratory status.

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) is a long-recognized and well-documented cause of secondary spontaneous pneumothorax,1,2 with an incidence of approximately 5% in postprimary (pulmonary) TB patients.3 Pleural infection results from rupture of subpleural caseous lesions, resulting in accumulation of a chronic empyema. A bronchopleural fisutla may occur spontaneously during the natural history of the disease, though it is more frequently caused by trauma or attempted surgical intervention. Both chronic empyema and bronchopleural fistula may result in spontaneous (and subsequent tension) pneumothorax, the latter with a more acute presentation. Tube thoracostomy is the indicated treatment, in conjunction with appropriate pharmacologic management of TB and other infections.3–5

CASE 1

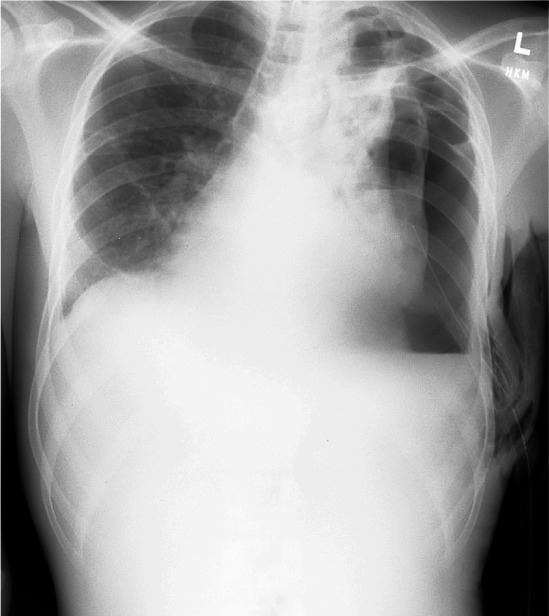

A 32-year-old male, with known human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), presented to the emergency department (ED) with progressively worsening difficulty in breathing. Chest radiograph showed pneumothorax and air-fluid level on the left side. Tube thoracostomy was performed, with improvement in symptoms and pneumothorax (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chest radiograph after tube thoracostomy of a 32-yearold male with shortness of breath, with improvement in respiratory status and lung expansion with persistent left-sided air-fluid level and pneumothorax. (All patient images taken with permission of patient or accompanying guardian.)

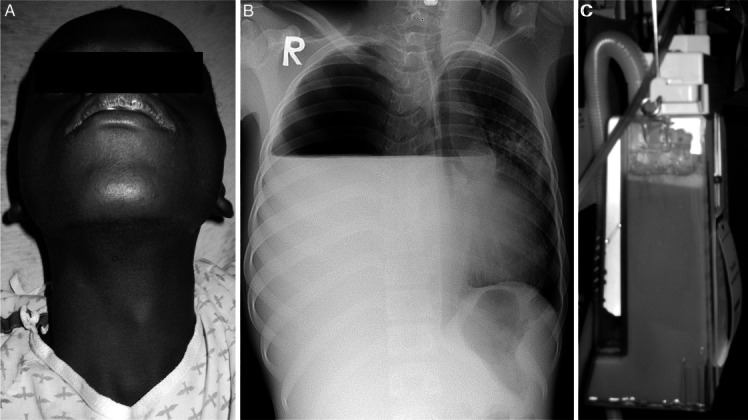

CASE 2

A 17-year-old male presented to the ED, via referral from an affiliate health center, with fever, cough, dyspnea, and tachypnea. Initial evaluation of the patient showed a young man in respiratory distress with tracheal deviation (Figure 2A). Chest radiograph (digital) confirmed tension pneumothorax with air-fluid level on the right side (Figure 2B). Tube thoracostomy was performed with copious purulent output under pressure (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

A, A 17-year-old male referred from the tuberculosis (TB) clinic for shortness of breath with evidence of tracheal deviation on examination of neck. B, Chest radiograph of 17-year-old male referred from TB clinic for shortness of breath reveals right-sided air-fluid level with pneumothorax and mediastinal shift. C, Purulent drainage from tube thoracostomy of patient with presumed TB effusion and pneumothorax. (All patient images taken with permission of patient or accompanying guardian.)

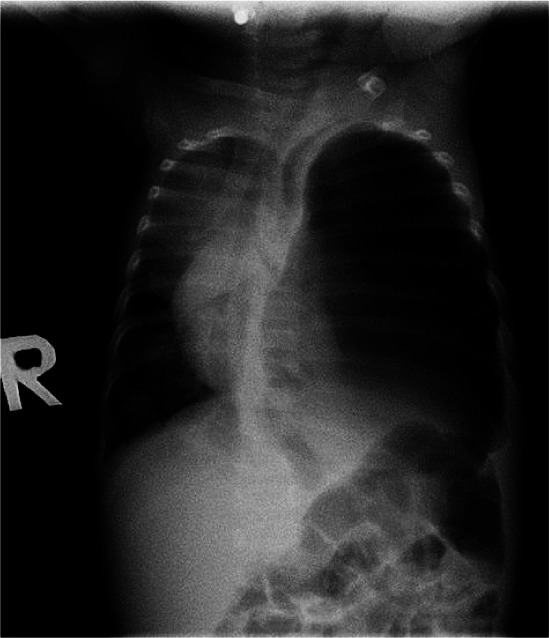

CASE 3

A 3-month-old female, brought in to the ED by her mother, had acute onset shortness of breath and respiratory distress after several weeks of cough and fever. Chest radiograph (digital, 2 views) revealed tension pneumothorax with mediastinal deviation (Figure 3). Tube thoracostomy was performed under intramuscular ketamine sedation, with purulent drainage and subsequent improvement in pneumothorax.

Figure 3.

Chest radiograph of 3-month-old infant with shortness of breath reveals presumed tuberculosis-related pneumothorax and resultant mediastinal shift. (All patient images taken with permission of patient or accompanying guardian.)

DISCUSSION

These patients were suffering from spontaneous tension pneumothorax with empyema secondary to presumed pulmonary TB. The patient in case 2 was sent from the TB treatment facility. All 3 patients improved after tube thoracostomy and drainage (via suction when available or gravity when not available) of the empyema. No acid-fast stain or culture test was available at John F. Kennedy Medical Center to confirm TB, although given the comorbidities and exposure, this was the presumed diagnosis.

Other causes of secondary spontaneous pneumothorax include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with emphysema, cystic fibrosis, lung cancer, other infection (including coccidioidomycosis, aspergillosis, histoplasmosis) and, in HIV-related disease, pulmonary Pneumocystis jiroveci.6

In Liberia, West Africa, with a population of approximately 3.8 million, TB has an estimated prevalence of 420/100,000,7 indicating a total population of approximately 16,000 active TB patients. TB incidence is growing at 2% annually in the general population. However, in the HIV population, the incidence of TB is growing at a much steeper 6.9%.8 TB and HIV are independently associated with spontaneous pneumothorax; however, in HIV patients with TB, the rate of pneumothorax increases dramatically.9 Thus, in Liberia, as in countries where TB is prevalent and HIV is growing, spontaneous pneumothorax will become an increasingly common pathologic condition and a cause of respiratory distress.

Acknowledgments

Support for clinical rotation at John F. Kennedy Medical Center, Monrovia, Liberia, was provided to Dr Grossman by the Yale/Stanford Johnson and Johnson Global Health Scholars Program and to both Dr Grossman and Dr Nasrallah by the HEARTT Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding, sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

Supervising Section Editor: Sean Henderson, MD

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

REFERENCES

- 1.Kahn IS. Spontaneous pneumothorax in pulmonary tuberculosis: its occurrence and management. South Med J. 1922;15:972–980. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gammons HF. Spontaneous pneumothorax complicating pulmonary tuberculosis. Boston Med Surg J. 1918;178:637–638. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim HY, Song K, Goo JM. Thoracic sequelae and complications of tuberculosis. RadioGraphics. 2001;21:839–860. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.4.g01jl06839. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sokolove PE, Derlet RW. Tuberculosis. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, editors. Rosen's Emergency Medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Light RW, Lee YCG. Pneumothorax, chylothorax, hemothorax, and fibrothorax. In: Mason RJ, Broaddus VC, Martin TR, editors. Murray and Nadel's Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2010. et al, eds. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pereira ML, Marchiori E, Zanetti G. Spontaneous pneumothorax as an atypical presentation of pulmonary paracoccidiomycosis: a case report with emphasis on imaging findings. Case Report Med. 2010;2010:961984. doi: 10.1155/2010/961984. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Liberia: health profile. Available at: http://www.who.int/gho/countries/lbr.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2010.

- 8.World Health Organization. Liberia: TB country profile. Available at: http://apps.who.int/globalatlas/predefinedReports/TB/PDF_Files/lbr.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2010.

- 9.Tumbarello M, Tacconelli E, Pironnti T. Pneumothorax in HIV-infected patients: role of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and tuberculosis. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:1332–1335. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10061332. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]