Abstract

Three waves of data from a prospective longitudinal study in Sierra Leone were used to examine internalizing trajectories in 529 war-affected youth (ages 10-17 at baseline; 25% female). Latent class growth analyses identified four trajectories: a large majority of youth maintained lower levels of internalizing problems (41.4%) or significantly improved over time (47.6%) despite very limited access to care; but smaller proportions continued to report severe difficulties six years post-war (4.5%) or their symptoms worsened (6.4%). Continued internalizing problems were associated with loss of a caregiver, family abuse and neglect, and community stigma. Despite the comparative resilience of most war-affected youth in the face of extreme adversity, there remains a compelling need for interventions that address family- and community-level stressors.

Keywords: War, children, Africa, adolescents and youth, child soldiers, resilience, mental health, internalizing problems

Worldwide, over 1 billion children live in countries affected by armed conflict (UNICEF, 2008). For young people, the effects of war are catastrophic—both as a direct result of witnessing and participating in acts of violence (Machel, 1996) as well as the indirect effects of the consequences of war on social, community and family structures (Patel, Flisher, Hetrick, & McGorry, 2007). High rates of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress reactions have been reported for war-affected children and youth throughout the globe, including in Sub-Saharan Africa (Bayer, Klasen, & Adam, 2007; Betancourt, Brennan, Rubin-Smith, Fitzmaurice, & Gilman, 2010), Asia (Kinzie, Sack, Angell, Manson, & Rath, 1986; Kohrt, 2007) and the Middle East (Ahmad, 2008; Thabet, Abed, & Vostanis, 2004). It is estimated that the level of untreated mental disorders in low- and middle-income countries (LAMICs) is upwards of 70% (Gore et al., 2011; Patel et al., 2007), a figure which is likely even higher for children and adolescents (Jacob et al., 2007). However, little is known about the course of mental health problems among children in conflict zones, nor the particular subgroups requiring treatment attention.

Like many civil conflicts, Sierra Leone’s war (1991-2002) was characterized by severe and pervasive violence, displacement and loss as well as the involvement of children (often by force) into several fighting forces including the rebel forces of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), the Sierra Leonean army, and civilian defense forces (CDF). These young people, often referred to as “child soldiers,” experienced forced abduction, family separations, repeated exposure to and involvement in violence as well as frequent physical and sexual abuse (Betancourt et al., 2010; Denov, 2007). However, our understanding of the long-term impact of violence on young people is limited, in part due to the cross-sectional orientation of much of the research. Research to date on war-affected youth has also maintained a predominant focus on PTSD despite the reality that global burden of mental illness related to depression deserves equal, if not greater attention, particularly in conflict-affected countries (Bolton & Betancourt, 2004). Depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide. It ranks fourth among leading causes of the global burden of disease overall and second for individuals between the ages of 15-44 (Mathers & Loncar, 2006; World Health Organization, 2008). Depression is often co-morbid with PTSD and has been found at very high levels among children and youth affected by war (Kohrt et al., 2008).

With limited longitudinal research to draw from, there remains significant debate regarding the course and persistence of mental health problems among war-affected young people over time. In the absence of treatment, some studies report maintenance of high symptom levels many years following violent conflict (Dyregrov, Gjestad, & Raundalen, 2002; Sack et al., 1993). For instance Dyregov found that, while war-affected Iraqi children showed a small reduction in sadness and other symptoms of depression over a two year period, overall levels of symptoms in the sample remained high. Other studies have observed that depression and internalizing symptoms may attenuate over time. For instance, Sack and colleagues (1993) found that, over six years of follow-up, cases of unipolar depression declined from 50% to 6% while PTSD cases in their sample of Cambodian refugee adolescents were maintained at 38% (reduced from 50% at time 1). In a more recent study, Panter-Brick and colleagues (2011) found that one-year follow up assessments of mental health among war-affected youth in Kabul, Afghanistan showed significant improvements in depressive symptoms, but found that symptoms of PTSD did not change.

Ultimately, it is likely that the longitudinal course of mental health symptoms in war-affected youth follows a significantly more complex pattern than has been reported to date. Trajectories may vary according to a number of factors including the nature of the outcome being examined, the historical-political context of the conflict, community perceptions of the involvement of young people in armed forces, individual war exposures and the dynamics of risk and protective factors in the post-conflict environment (Betancourt & Khan, 2008; Panter-Brick, et al., 2011). For example, there is strong evidence to indicate the adverse effects of specific war exposures (e.g., witnessing killings, being threatened, separation from family members) along with null effects for others (e.g., carrying dead bodies or wounded persons, being forced to fight) (Allwood, Bell-Dolan, & Husain, 2002; Morgos, Worden, & Gupta, 2007).Moreover, war experiences alone do not fully explain the dramatic variations in depression symptoms and other internalizing problems documented among war-affected youth (Betancourt et al., 2010; Kohrt, 2009). A growing literature has identified the need to look beyond war-related traumatic experiences to analyses that also include post-conflict social factors (e.g., post-conflict stigma), stressors (e.g. economic hardship) and resources (e.g., community and family support) to examine factors influencing long-term mental health adjustment (Betancourt et al., 2010; Miller & Rasmussen, 2010).

Studies of war-affected populations have found that depression is not always influenced by the same predictors as PTSD or hostility (Durakovic-Belko, Kulenovic, & Dapic, 2003; Pham, Vinck, & Stover, 2009). For example, in a study of war-affected youth in Sarajevo, Duraković-Belko and colleagues (2003) found that female gender was the strongest predictor of depressive symptoms, whereas traumatic loss significantly predicted posttraumatic stress reactions. Similarly, Betancourt and colleagues (2010) found that war-related exposures of victimization such as rape were more strongly predictive of internalizing problems, while the experience of violence perpetration such as killing or injuring others was more closely linked to externalizing problems.

While longitudinal studies have the capacity to identify specific predictors of change in outcomes over time, person-oriented methods (i.e., latent class growth analysis) can differentiate latent trajectory groupings within a sample (Sterba & Bauer, 2010). Such approaches challenge the assumption that individuals share the same pattern of symptom expression over time. They do so by identifying discrete patterns of symptom trajectories across subjects; for example, distinguishing those subgroups within a population that exhibit sustained, heightened symptom levels from those that start at high levels and attenuate over time. This methodology has been applied in a diversity of settings to evaluate unique internalizing behavior trajectories among at-risk groups (Leadbeater & Hoglund, 2009; Sterba, Prinstein, & Cox, 2007). Importantly, person-oriented approaches allow for consideration of the systems theory principles of equifinality—the notion that the same mental health state may be arrived at via unique qualitative trajectories— and multifinality—the notion that divergent mental health states may be arrived at as a result of the same etiologic factors (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1996; Layne et al., 2010). Despite the importance of the concepts of equifinality and multifinality, they have yet to be applied to their full capacity in analyses of war-affected populations, principally because of a paucity of longitudinal data.

Of parallel importance is a developmental and ecological framework for understanding the effects of concentrated adversity on youth (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 2005). Delineation of risk and protective factors at the individual (ontogenetic), familial (microsystem) and community or societal levels (exosystems and macrosystems) allows for consideration of multiple layers of influence that shape a child’s mental health and development (Betancourt & Khan, 2008; Betancourt, Meyers-Ohki, Charrow, & Tol, In press; Leadbeater, Schellenbach, Maton, & Dodgen, 2004). In conflict and post-conflict settings, an ecological perspective is particularly vital as war not only represents risk of personal physical endangerment, but also disruption to the environment in which healthy child development occurs (Betancourt & Khan, 2008). Wars herald the loss of security, predictability and the structure of family units, which influence attachment relationships and the child’s sense of protection. For example, lack of a supportive and secure family environment in the five-years following war was shown to result in higher stress-related symptoms among war-affected Croatian refugee children (Adjukovic & Adjukovic, 1998). Furthermore, essential community services and institutions, such as schools, health systems and religious institutions are often damaged or purposefully destroyed in conflict, and social networks are undermined (Barenbaum, Ruchkin, & Schwab-Stone, 2004). The loss of routines, access to education, economic security and damage to the social infrastructure in communities affected by war has implications for levels of internalizing problems in children and youth as well as other forms of psychosocial adjustment.

The present study of war-affected youth in Sierra Leone was designed to examine the pattern of responses to war experiences and post-conflict factors on mental health and social reintegration among male and female youth, including a large proportion of former child soldiers, who lived through the country’s 11-year civil conflict. Assessments were conducted in the immediate post-conflict period, and twice more in the following six years. Using a prospective design, this study followed a cohort of war-affected youth from the end of the civil war (when young people in the sample were 10-17) into late adolescence and young adulthood. War experiences and age, as well as post-conflict risk and protective factors, were hypothesized to be associated with different trajectories of internalizing symptoms across the three time periods of observation.

Specifically, it was hypothesized that multifinality—i.e. several qualitatively unique trajectories of adjustment—would better characterize internalizing problems over time as compared to a single, unified trajectory. Additionally, we anticipated that trajectory membership would be predicted by differences in war exposures as well as post-conflict resources, supports and adversities. To account for the social ecological context of these youth, we included predictor variables at individual (e.g., victim of rape, access to school), family (e.g., post-conflict family support as well as abuse and neglect) and community (e.g., perceived community acceptance and stigma) levels. Given our prior findings on the particular importance of family-level factors in predicting internalizing outcomes (Betancourt et al., 2010), we anticipated that death of a parent due to war and the post-conflict family environment would be more influential than war trauma exposures in describing the different trajectory classes of internalizing problems.

METHOD

Participants and Setting

Male and female war-affected youth (25% female, ages 10-17 at baseline) were interviewed at three time points: T1 (2002), T2 (2004), and T3 (2008). The sample comprised three groups: former child soldiers who had received services through NGO-run Interim Care Centers (ICCs) during the most active period of demobilization (June 2001-February 2002) (N = 264), a community sample of war-affected youth not served by ICCs (N = 137), and a cohort of self-reintegrated former child soldiers recruited at T2 (N = 127). ICC-served youth in five districts of Sierra Leone (Bo, Kenema, Kono, Moyamba and Pujehun) were identified according to International Rescue Committee (IRC) registries. The community sample was recruited via random door-to-door sampling in these same communities of resettlement; this cohort was screened to ensure no prior involvement with reintegration services or ICCs. At the time of recruitment, it was not considered ethically permissible to inquire about community comparison participants’ former involvement in fighting forces during the war. A significant number of individuals within this cohort were later identified as being self-reintegrated former child soldiers, precluding the possibility of adequately comparing those who were and were not former soldiers due to the limited number of individuals who indicated no involvement with an armed group.

In 2004, an additional cohort of self-reintegrated child soldiers (N = 127) identified from outreach lists compiled by an NGO in the Bombali district of Sierra Leone was added to the study. T2 data collection was cut short due to the death of the IRC country director in a helicopter accident which halted all study activities at a time when only 58% of the original ICC served cohort had been re-contacted. However, at T3, the research team traced and re-interviewed 387 youth, comprising 73% of the full sample. An overview of the sample composition at each wave is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Size and Composition by Time Point and Gender.

| Time 1 (2002) | Time 2 (2004) | Time 3 (2008) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | |

| NGO-Supported Reintegration |

231 | 28 | 259 | 136 | 15 | 151 | 165 | 18 | 183 |

| Self-Reintegrated | - | - | - | 63 | 64 | 127 | 57 | 60 | 117 |

| Community Comparison Group |

97 | 39 | 136 | 46 | 12 | 58 | 67 | 20 | 87 |

| Total | 395 | 336 | 387 | ||||||

Participants enrolled from different geographical districts varied modestly on several key characteristic variables. The percentage of participants who were female ranged from 12% in Pujehun to 38% in Kenema, mean age at baseline ranged from 14.3 years in Moyamba to 16.8 years in Kenema and mean number of years spent in fighting forces ranged from 7.8 in Pujehun to 10.6 in Kono. In contrast, the cumulative number of war exposures was similar across groups, a finding which is unsurprising given the extensive nature of the violence which took place during the Sierra Leonean civil conflict. Based on the observed differences identified in these comparisons, region was included among demographic covariates in analyses. Status as a former child soldier was not included, again due to the observed pervasive nature of exposure to war-related violence among both former combatants and non-combatants and due to the fact that this variable was not significantly associated with any of the outcomes of interest.

Ethical approval was given by the Institutional Review Board of the Boston University Medical School-Boston Medical Center and the Harvard School of Public Health. Data for all participants were collected through in-home, one-on-one interviews conducted by Sierra Leonean research assistants trained and monitored by the study Principal Investigator and research staff. All participating youth provided verbal assent, and verbal consent was also provided by youth’s parent or guardian. Participation was not linked to receiving services. Among those approached and invited to partake in interviews, there were no refusals to participate at baseline. At each period of data collection, social workers traveled with the research team to respond to serious risk of harm situations (e.g., suicidality) and make referrals to local service programs as appropriate. At T3, 5% of the sample received additional mental health services from community partners due to such immediate risk of harm issues.

Measures

A mix of locally-derived measures and standard measures validated for cross-cultural use were employed. Qualitative data collection and in-depth consultation with Sierra Leonean staff and community members were used to select and adapt all measures (Betancourt et al., 2010). Following a standardized protocol (Van Ommeren et al., 1999), measures were forward- and back-translated from English to Sierra Leonean Krio, the local language spoken by all participants and interviewers, in order to ensure accuracy of measurement. Following the first round of interviews in 2002, survey instruments were refined in order to better reflect significant themes and concepts that emerged from qualitative data collection. As a result, at T2 collective efficacy and perceived stigma measures were added, and at T3 family abuse and neglect and daily hardship measures were added (see full instrument descriptions below).

Mental Health Outcomes

Internalizing Emotional and Behavioral Problems

A dimensional scale of internalizing problems was taken from the Oxford Measure of Psychosocial Adjustment developed and validated for use among former child soldiers in Sierra Leone and northern Uganda (MacMullin & Loughry, 2004). The instrument was used at all assessment periods (T1-T3). In prior research, these scales have shown strong predictive validity between theoretically associated constructs and strong correlations with other standard measures of mental health outcomes used in research with war-affected children (Betancourt et al., 2010). For the current analysis, the depression and anxiety subscales were combined to create a scale of internalizing symptom and problems. Examples of questions on this scale include “Are you afraid something bad will happen to you?” and “Do you cry easily?” (response options : never, hardly ever, sometimes, always). The reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s alphas) associated with this scale were α = 0.77 at T1, α = 0.82 at T2 and α = 0.76 at T3.

War Experiences

The Child War Trauma Questionnaire (Macksoud & Aber, 1996) was adapted for the Sierra Leone context and used to assess individual war experiences. The adapted instrument included 42 items describing a range of war exposures. Based on prior research (Betancourt et al., 2010), three specific war experiences thought to be exemplary of “toxic” forms of war-related trauma were examined—(1) being a victim of rape, (2) injuring or killing others, (3) death of primary caregivers due to war—to investigate the specificity of factors influencing internalizing trajectories.

Post-Conflict Factors

Post conflict factors were also selected in light of recent research indicating that stressors in the post-conflict environment deserve equal if not more attention in understanding the longer term adjustment of war-affected children, youth and families (Miller & Rasmussen, 2010). Findings from prior waves of the study increased our interest in post-conflict family relationships with particular attention to abuse and neglect. The Family Relations Scale, implemented at T3, was adapted from the Child Trauma Questionnaire (Bernstein, Fink, Handelsman, & Foote, 1994) and includes items that assess levels of family support, discipline, abuse, and neglect in the period after the end of the war. Specifically, it investigates five types of maltreatment: emotional, sexual and physical abuse, as well as emotional and physical neglect. Sound sensitivity and convergent validity have been reported previously (Bernstein, Ahluvalia, Pogge, & Handelsman, 1997) and the subscale for physical abuse and neglect (three items) demonstrated good internal consistency in this sample (T3 Cronbach’s alpha = .73). An example of a question within this measure is “How often did you get hit so hard that you were very injured and it took a long time to heal?” (response options: never, hardly ever, sometimes, and always).

Perceived Community Acceptance

A scale of perceived community acceptance was developed from locally-collected qualitative data collected in 2002 and administered at all three waves; as with all predictive measures, the value at the earliest time point available (in this case, T1) was utilized in analyses. The perceived community acceptance scale consists of six items that reflect locally-important indicators of perceived community acceptance among war-exposed youth. These items scored on a Likert scale, were not phrased to refer specifically to the experience of being a former child soldier but referred to community relationships in general. The Perceived Community Acceptance scale demonstrates strong internal consistency within this sample (T1 Cronbach’s α = .88). Examples of questions asked include “Adults in the community like you?” and “People in this community want you to do better?” (response options: not true, sometimes or somewhat true, very true).

Social Disorder and Intergenerational Closure

At T2 and following, scales for Social Disorder and Intergenerational Closure were drawn from a scale of collective efficacy (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997) previously adapted for youth in sub-Saharan Africa. These were selected as important social ecological constructs, particularly for a collectivist society like that of Sierra Leone. The social disorder subscale included 5 items (T2 Cronbach’s α = .68) assessed level of criminal activity within the community (e.g., “In the past month were there thefts or other crimes in your community?”), whereas the intergenerational closure subscale (T2 Cronbach’s α = .74), comprising 7 items, assessed the degree to which community members and elders knew the local children and exerted informal social control, protection and guidance of children (e.g., “Are there elders that make sure that children don’t get in trouble?”).

Perceived Stigma

At T2 and following, perceived stigma was assessed using an adaptation of the Everyday Discrimination Scale (Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997). This scale captures negative community interactions such as differential treatment, threats, or abuse due to discrimination based on gender, race or participation as a child soldier. Questions were asked in two parts: first, the frequency of a discriminatory activity (e.g. “How often do you receive bad looks when you go to the market or other places where [members of the community] sell?”), and secondly, the perceived reason for this (e.g. “Because you are a former child soldier”, “Because of your gender”, “Because you have a disability” etc.). Discrimination specific to being a former child soldier was used in the present analysis. In the current sample there was a high internal consistency of the discrimination items for child soldier perceived stigma (T2 Cronbach’s α = .80). This scale was seen as applying broadly to the sample since many of the youth in the community cohort indicated a history of involvement in armed groups as well as the other two groups purposively sampled from registries of known former child soldiers.

Daily Hardships

At T3, an adapted Post-War Adversities Index (Layne, Stuvland, Saltzman, Djapo, & Pynoos, 1999) was added to assess daily hardships facing youth in the post-conflict context. Items assess hunger, housing, economic insecurity and interpersonal adversities (e.g., “During the past six months, have you (your family) been evicted from your habitation, or forced to move into worse accommodations than you previously had?”). The scale demonstrated high internal consistency (T3 Cronbach’s α = .82).

Functional Impairment and Risky Behavior

Four measures of functional impairment and risky behavior were assessed at T3, and were utilized in secondary analyses to examine the extent to which youths’ internalizing trajectories were related to such outcomes (see Data Analysis section). Functional impairment was operationally defined in terms of (1) the number of days in the month over which the participant was unable to work because of health-related, emotional of psychological problems, and (2) the level of difficulty participants had carrying out household responsibilities over the past month because of such problems (response options: none, a little, some and a lot). In addition, two indicators of risky behavior were utilized: (1) whether, in the past month, the participant was involved in a physical fight or altercation, and (2) whether the participant had ever been in trouble with the police or law (Centers for Disease Control, 2005). These items were used to examine the clinical significance of the internalizing symptoms reported by correlating them to functional impairments.

In addition, demographic and household information such as gender, age, and socioeconomic status (SES) was collected at each survey period using items on the UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (UNICEF, 2007).

Data Analysis

Data analysis comprised four parts: First, trajectories were estimated across the three time points at which internalizing symptoms were assessed, using a semiparametric mixture model (Nagin & Tremblay, 2001; Roeder, Lynch, & Nagin, 1999). This procedure calculates the probability that each individual belongs to a particular group trajectory, based on their observed longitudinal pattern of internalizing symptoms, and then determines assigned group membership using the highest classification probability across trajectories (for examples, see: Duchesne, Larose, Vitaro, & Tremblay, 2010; Joussemet et al., 2008). Mean probabilities within trajectories of 0.7 or higher are considered to imply a good fit (Nagin, 2005). Models of two to six trajectories were evaluated, and the model of best fit was selected based on the sample-size-adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). For the outcome, internalizing problems, the level of missingness was 26% at T1, 37% at T2 (the higher percentage reflects early termination of data collection at this wave) and 27% at T3. Missingness of T1 data due to entry in the study at T2 is related to subject characteristics for the self-reintegrated group and thus fits the classic definition of data missing at random (MAR), while T2 data missing due to cessation of project activities fits the model of data missing completely at random (MCAR) insofar as not being related to subject characteristics (Little & Rubin, 1987). Studies have shown that under these circumstances, particularly data MCAR, Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) methods as used here are unbiased, efficient, and provide excellent estimates of standard errors in longitudinal models, even with rates of missing data at 50-75% (Muthén & Muthén, 2010; Newman, 2003). As such, FIML was used to address missing data in the latent class growth analyses.

Second, pre-specified predictor variables of class membership were inspected through pairwise correlations to evaluate potential collinearity among variables. Associations greater than r = 0.40 were flagged as representing potentially overlapping constructs and upon further inspection were removed from analyses as relevant. All pairwise associations among predictor variables are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Pairwise Correlation Matrix of Associations Among Independent Variables.

| Age | Gender | SES | Bo | Kene -ma |

Kono | Makeni | Moy- amba |

Puje- hun |

Raped | Perpe- tration |

Paren t death |

Family Abuse |

Soldier Stigma |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, T1 | ||||||||||||||

| Gender | −0.10* | |||||||||||||

| SES, T1 | 0.03 | −0.06 | ||||||||||||

| Bo † | 0.13** | 0.03 | −0.03 | |||||||||||

| Kenema † | 0.13** | 0.20+ | −0.01 | --- | ||||||||||

| Kono † | 0.03 | −0.52*** | −0.06 | --- | --- | |||||||||

| Makeni † | −0.19*** | 0.53*** | 0.05 | --- | --- | --- | ||||||||

| Moyamba † | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.09+ | --- | --- | --- | --- | |||||||

| Pujehun † | 0.02 | −0.23 | 0.02 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||||||

| Victim of Rape | 0.02 | 0.69*** | 0.00 | −0.10 | −0.05 | −0.25** | 0.40*** | --- | −0.16 | |||||

| Killed/Injured Others | 0.09+ | −0.15+ | −0.06 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.11 | 0.17* | 0.14 | −0.12 | 0.23* | ||||

| Parent Death | −0.04 | 0.10 | −0.10* | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.02 | −0.32+ | --- | 0.16+ | 0.08 | |||

| Family Abuse, T3 | −0.21*** | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.04 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.13** | 0.06 | ||

| Child Soldier Stigma, T2 | 0.04 | 0.12** | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.03 | −0.14** | 0.14** | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.17*** | 0.37*** | 0.10* | 0.06 | |

| Hardship, T3 | −0.06 | −0.02 | −0.20** | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.04 | −0.02 | −0.06 | −0.06 | 0.06 | 0.14* | 0.16** | 0.31*** | 0.17* |

| Social Disorder, T2 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.05 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.13** | 0.09+ | 0.18*** | 0.10+ | 0.13** | 0.35*** |

| Comm. Acceptance, T1 | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.16*** | −0.18*** | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.06 | −0.14** | −0.10* | 0.00 | −0.24*** |

| Intergen. Closure, T2 | −0.10* | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.10* | −0.03 | 0.08+ | −0.03 | −0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | −0.07 | −0.10* | −0.08 | −0.17*** |

| Hardship, T3 | Social Disorder, T2 | Comm. Acceptance, T1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Disorder, T2 | 0.18** | ||

| Comm. Acceptance, T1 | −0.03 | −0.17*** | |

| Intergen. Closure, T1 | −0.16** | −0.14** | 0.28*** |

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

Regional districts from which participants were recruited within Sierra Leone. For all binary measures, 0=No and 1=Yes. Gender: 0=Male, 1=Female.

Third, multinomial logistic regression analyses were conducted in order to evaluate the predicted value of war and post-war risk and protective factors related to group trajectory membership. These analyses tested the respective contributions of different classes of predictors—war exposures, post-conflict protective factors such as perceived community acceptance, and post-conflict risk factors such as perceived stigma—and were therefore entered as separate steps into the multinomial logistic regression analyses: i.e., after the entry of demographic variables and war exposures (step 1), post-conflict risk factors were added to the model (step 2), followed by post-conflict protective factors (step 3). For the 18 independent variables used in the models, the average level of missingness, assumed to be MAR, was 13% (N = 69/529). Prior to the multinomial regressions, an expected maximum (EM) and Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) routine was used to create 99 multiply imputed data sets for analysis (SAS PROC MI v9.2; SAS Institute Inc, 2008).

As a final step, regression analyses were conducted to evaluate whether trajectory membership was associated with functional impairment or risky behavior at T3. Previous studies, often in Western settings, have concluded disparate results as to whether heightened internalizing symptoms affect the day-to-day functioning of individuals (Hays, Wells, Sherbourne, Rogers, & Spritzer, 1995; Luthar, 1991).

RESULTS

Trajectories of internalizing levels

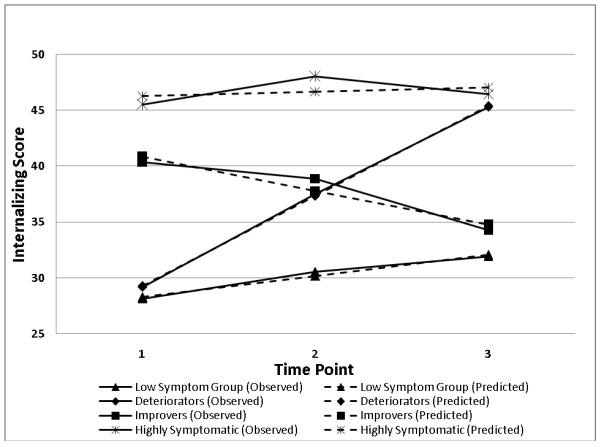

Models from two to six groups were estimated in Mplus v6 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). Based on the adjusted BIC, the four-group solution (BIC = 7491) was considered optimal; the four-group model was found to be significantly better than the one-(BIC = 7508, p = .008) and three-group (BIC = 7498, p = .05) solutions. Additionally, while the two-(BIC = 7494), five-(BIC = 7492) and six-group (BIC = 7498) models were not significantly different from the four-group model solution (p > .05), the four group solution represented the best overall fit and conceptual clarity. As confirmation, mean assignment probabilities of belonging to a particular group ranged from 0.73-0.76, indicating a good fit of this final model (D.S. Nagin, 2005). Figure 1 depicts the observed mean trajectories of the four groups (mean scores for individuals within groups) represented as solid lines, as compared to predicted group trajectories (based on the model’s coefficient estimates) represented as dashed lines. Table 2 provides descriptive information of the sample composition separated into each of the four trajectory classifications.

Figure 1.

Estimated Mean and Predicted Trajectories of Former Child Soldiers’ Reports of Internalizing Symptoms across Three Post-war Time Points.

Table 2.

Descriptive Characteristics of the Sample According to Internalizing Trajectory Group Membership.

| Total sample N=529 |

Low Symptoms N=219 |

Improvers N=252 |

Deteriorators N=34 |

High Symptoms N=24 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, T1, Mean (SD) | 14.48 (2.43) | 14.6 (2.32) | 14.88 (2.31) |

14.36 (2.46) | 16.0 (2.34) |

| Gender (females), N (%) | 131 (24.8%) | 39 (17.8%) | 77 (30.6%) | 7 (20.6%) | 8 (33.3%) |

| SES, Mean (SD) | 8.05 (2.09) | 7.91 (2.04) | 8.21 (2.13) | 8.13 (2.42) | 7.72 (1.62) |

| Victim of rape, N (%) | 70 (13.2%) | 14 (7.9%) | 42 (20.9%) | 6 (17.6%) | 8 (33.3%) |

| Killed or injured others, N (%) | 141 (26.7%) | 45 (25.3%) | 68 (33.8%) | 14 (41.2%) | 14 (58.3%) |

| Death of Parent, N (%) | 122 (23.1%) | 37 (16.9%) | 56 (22.2%) | 18 (52.9%) | 11 (45.8%) |

| Family Abuse & Neglect, T3, Mean (SD) |

1.10 (1.51) | 0.8 (1.30) | 1.11 (1.48) | 1.88 (1.64) | 2.0 (2.12) |

| Perceived stigma, T2, Mean (SD) | 2.89 (3.84) | 1.30 (2.68) | 3.54 (3.78) | 4.25 (4.29) | 6.74 (5.59) |

| Daily Hardship, T3, Mean (SD) | 4.95 (3.44) | 4.18 (3.34) | 5.01 (3.35) | 6.59 (3.51) | 7.58 (2.58) |

| Social Disorder, T2, Mean (SD) | 3.92 (1.55) | 3.64 (1.37) | 4.06 (1.62) | 3.73 (1.42) | 5.12 (1.72) |

| Perceived Com. Acceptance, T1, Mean (SD) |

10.70 (2.31) | 10.97 (1.93) | 10.40 (2.55) |

11.52 (1.31) | 10.0 (3.43) |

| Intergenerational Closure, T2, Mean (SD) |

6.18 (1.40) | 6.37 (1.14) | 6.08 (1.52) | 5.95 (1.20) | 6.00 (1.71) |

Of the four groups, the largest represented 47.6% (N = 252) of the total sample and denoted a trajectory designated as improvers who demonstrated moderate levels of internalizing problems at baseline but a significant decline in symptoms across the three time points (mean change = −5.1; t (251) = −8.2, p < .001). By comparison, the second largest group (41.4% of the sample, N = 219) was given the label low symptoms and exhibited a relatively flat trajectory of internalizing problem scores, which started low and only modestly increased over time (mean change = 2.9; t (218) = 4.58, p < .001). This low symptom group was utilized as the reference group against which other trajectories were compared in multinomial regression analyses. The second smallest (6.4%, N = 34) and smallest groups (4.5%, N = 24) were characterized by increasing-symptom and stable-high trajectories over time. The 34 youth in the group labeled deteriorators exhibited a pattern of initially low internalizing problems marked by significant increases over time (mean change = 14.0; t (33) = 10.2, p < .001). The last group, labeled as high symptoms had high baseline levels of internalizing problems which persisted over time (mean change = 2.0; t (23) = .97, p > .05).

Multinomial logistic regression analyses were conducted to investigate potential relationships among war exposures, post-conflict risk and protective factors, and trajectory group membership. To reflect this framework and the temporal dimension of predictor variables encapsulated by it (i.e., war exposures followed by post-war factors), regression models were developed in three steps: In the first step, demographic variables (covariates) were included alongside war exposures; in the second step, post-conflict risk factors were included; and in the third step, post-conflict protective factors were added. Each of the three steps improved model fit as assessed by change in −2 log likelihood at the 0.05 alpha-level. Further statistical results of the multinomial regression analyses are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Results: Three Trajectories of Internalizing Symptoms, Relative to Low Symptoms Group.

| Model Fit Statistics | Group-Specific Odds Ratio Estimates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Likelihood Ratio Test (df) |

p | High Symptoms | Deteriorators | Improvers | |

| Step 1 | 69.91(33) | <0.001 | |||

| Intercept | 0.0002** | 0.00003*** | 0.14+ | ||

| Age | 1.26* | 1.14 | 1.14** | ||

| Gender | 2.09 | 1.35 | 2.29** | ||

| SES | 1.05 | 1.19 | 1.07 | ||

| Victim of Rape | 1.95 | 1.23 | 1.26 | ||

| Killed/Injured Others | 1.11 | 1.00 | 0.89 | ||

| Death of Parent due to War | 1.64 | 4.03** | 0.94 | ||

| Step 2 | 84.28(12) | <0.001 | |||

| Family Abuse & Neglect | 1.50* | 1.43* | 1.19+ | ||

| Child Soldier Stigma | 1.27*** | 1.21** | 1.14** | ||

| Hardship | 1.18 | 1.19* | 1.04 | ||

| Social Disorder | 2.10* | 0.97 | 1.26+ | ||

| Step 3 | 16.15(6) | <0.05 | |||

| Perceived Com. Acceptance | 0.90 | 1.26+ | 0.91* | ||

| Intergenerational Closure | 1.10 | 1.01 | 0.91 | ||

p<0.10;

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001.

All reported odds ratios and significance tests are reflective of values derived from the full (final) model. Males served as the reference group for sex and the low symptoms group served as the comparison group for model tests and odds ratios. Regional districts in Sierra Leone from which participants were recruited was also included as a covariate in the final model, but were non-significant and were therefore not included in the Table.

High Symptom Group (vs. Low Symptom Group)

Results from the final model, which included three steps, found that the probability of being in the high symptom trajectory was greater for those individuals who were older (odds ratio (OR) = 1.26, p < 0.05), experienced family abuse and neglect (OR = 1.50, p < 0.05) as well as perceived stigma for their role as a former child soldier (OR = 1.28, p < 0.001), as well as higher levels of social disorder within the community (OR = 2.10, p < 0.05).

Deteriorator Group (vs. Low Symptom Group)

Membership in the deteriorator trajectory group (those whose internalizing symptoms worsened over time) was associated with a much greater probability of having a parent die due to war (OR = 4.03, p < 0.01), as well as family abuse and neglect (OR = 1.43, p < 0.05) perceived stigma (OR = 1.21, p < 0.01) and higher levels of daily hardships (OR = 1.19, p < 0.05) in the post-war environment.

Improver Group (vs. Low Symptom Group)

Results from analyses found that the probability of belonging to the improver group was higher for those who were older (OR = 1.14, p < 0.01) and who reported starting at higher levels of perceived stigma upon resettlement as compared to the low symptom group (OR = 1.14, p < 0.01). In terms of protective factors, perceived community acceptance (OR = 0.91, p < 0.05) demonstrated a positive influence on odds of membership in the improver group.

Secondary regression analyses were conducted to investigate the relationship between internalizing trajectory membership and functional impairment as well as risky behaviors at T3. Relative to the low symptom group, the high symptom group missed more days of work (β = 3.60, p < 0.05) and had greater difficulty with household responsibilities (β = 2.48, p < 0.001) due to a health-related, emotional or psychological problem over the month prior to interview at T3; high symptom membership was also associated with greater likelihood of being in a physical fight over the past month (β = 4.77, p < .001) and having ever been in trouble with the police(β = 3.09, p < 0.001). Similarly, membership in the deteriorator group was associated with more missed days of work or being unable to do work (β = 3.38, p = 0.01), greater difficulty with household responsibilities (β = 1.48, p < 0.001) and greater likelihood of having been in a physical fight (β = 3.18, p < 0.05) in the past month, as compared to the low symptom group. In comparison, at T3 there were no differences on these four outcomes when comparing the improver trajectory with the low symptom trajectory.

DISCUSSION

This study presents the first trajectory analysis of internalizing symptoms among war-affected youth, a large proportion of which were former child soldiers. Given this context, it is especially noteworthy that a large majority—89% (N = 471/529)—of the sample demonstrated either low internalizing symptom levels or improvement over time relative to the highly symptomatic groups, despite markedly limited access to care. Previous studies that have similarly investigated the mental health of war-affected youth over time have arrived at disparate conclusions: some have found maintenance of high symptom levels many years following violent conflict (Kinzie, Sack, Angell, Clarke, & Ben, 1989; Sack, et al., 1993), while others have found an attenuation of symptoms over time (Adjukovic & Adjukovic, 1998; Laor, Wolmer, & Cohen, 2001; Weine et al., 1995). However, examining mental health problems by relying on summary mean scores at each time point can mask rich patterns of variability within in sample over time. To date, no such studies on war-affected youth have approached this question using latent class growth analyses, which allow for the classification of multiple trajectories within a cohort. Our findings speak to the comparative resilience of the majority of these youth in the face of extreme adversity, including exposure to particularly toxic war experiences and a context of post-conflict impoverishment.

It is noteworthy that smaller groups of youth in the sample experienced consistently high levels of psychological distress (4.5%), or reported a significant increase in symptoms over time (6.4%). These groups are of greatest concern, particularly given the limited access to mental health services in this and many post-conflict settings. Membership in one of these trajectories was also associated with higher levels of functional impairment including inability to carry out work responsibilities or perform household duties within one month of interview at T3, as well as greater likelihood of having been in a physical fight or in trouble with the police—all of which highlight the noteworthy functional impairments associated with poor trajectories of internalizing.

The current findings are consistent with arguments for increased attention to post-conflict stressors rather than a narrow focus on war-related trauma and PTSD which has dominated much of the research on the mental health of war-affected youth (Miller & Rasmussen, 2010). Of note, the 10.9% of youth who demonstrated persistently high symptoms of internalizing or increases in internalizing problems over time were characterized by family abuse and neglect (OR=1.50 for the high symptom group, OR=1.43 for deteriorators), as well as perception of stigma (OR=1.27, OR=1.21 respectively) in the post-war setting. Consistently high rates of internalizing symptoms across waves of assessment were also associated with older age (OR= 1.26), and social disorder in the community (OR=2.10), while youth who reported deteriorating symptoms were more likely to have experienced the death of a parent during war (OR=4.03) and suffer post-conflict daily hardships (OR= 1.19). Recent research has called for more detailed “unpacking” of the specific relationships between different conflict-related and post-conflict factors in shaping mental health outcomes in children and adolescents (Betancourt, 2011; Layne, et al., 2010). In the present study, traumatic war experiences played a more limited role in predicting the trajectory of internalizing symptoms over time. Although experiencing rape and perpetration of violence have demonstrated associations with outcomes related to hostility and deficits in prosocial behaviors and attitudes previously (Betancourt, Borisova, et al., 2010; Betancourt, Brennan, et al., 2010), in the present analysis, the death of a parent due to war appeared to be the most robust war exposure related to membership in the deteriorating (OR=4.03) trajectory class of internalizing problems.

The finding that older age is associated with greater probability of membership in the high symptoms and improvers group trajectories is also noteworthy. Older age is partly indicative of a longer duration of involvement in fighting forces and greater war exposure, and it is likely that this had a negative impact on internalizing symptom levels at baseline. Following the war, these “overgrown” youth (Betancourt et al., 2008) may have also had difficulty adjusting among peers, as they were often much older than their peers at grade level (given interruptions to their schooling, particularly for child soldiers) but lacked basic skills (e.g. reading and writing) important for completing an education or securing viable employment.

Overall, our findings are consistent with a growing literature on the potent influence of post-conflict stressors on mental health in war-affected populations (Annan & Brier, 2010; Betancourt et al., 2010). Indeed, studies of war-affected adults have shown that factors such as financial hardship, family disintegration and displacement are more potent predictors of depression and anxiety than past traumatic experiences (Farhood et al., 1993; Miller, Omidian, Rasmussen, Yaqubi, & Daudzai, 2008). For example, Miller and colleagues (2008) found that daily stressors such as financial difficulties and unemployment were the strongest predictors of depression among Afghan war-affected men. Among Afghan women, war experiences had no relationship to depression, but were significantly predicted by daily stressors. Overall, the literature points to important sensitivities in the relationship between post-conflict stressors and mental health, particularly internalizing problems (Gorst-Unsworth & Goldenberg, 1998; Rasmussen et al., 2010).

The implications of these findings are extremely important with regards to the post-conflict development agenda. Despite Sierra Leone’s wealth of natural resources, the population continues to suffer from extreme levels of poverty, displacement, and poor infrastructure. Current estimates are that 46% of Sierra Leone’s youth are unemployed or underemployed (ILO-UNDP, 2010). War experiences may indeed set into motion a cascade of family and community risk processes including daily hardships and social disorder which, in our sample, were significantly associated with deteriorating and high symptom trajectories (respectively). For instance, many children in post-conflict settings experience family and community disintegration and are vulnerable to ongoing stressors such as abuse or discrimination (Annan & Brier, 2010; Klasen, Oettingen, Daniels, & Adam, 2010). Studies of war-affected families from Afghanistan and Palestine as well as research on US Military families indicate that exposure to war violence may increase emotion dysregulation leading to increased risk of family violence in the home (Dubow et al., 2010; Panter-Brick et al., 2011). When both caregivers and children are exposed, these risks are likely intensified and bidirectional. Poor family and community relationships following the end of armed conflict pose continuous threats to mental health and adjustment over time by creating chronic stress which may tax available coping resources (Miller & Rasmussen, 2010). In research to date, very little is known about what happens to war-affected and war-involved youth over time. Much more research should be directed at longitudinal and developmental research and the role of family and community processes over time.

Overall, the present study highlighted a set of social factors played an important role in the trajectories of internalizing problems examined. Death of a caregiver due to war, experience of family abuse or neglect and the perception of stigma related to one’s previous association with fighting forces consistently predicted membership in trajectories characterized by high or worsening symptoms of internalizing problems over time. These findings are consistent with prior research demonstrating the devastating effect of parental death in both conflict and non-conflict affected settings (Betancourt et al., 2010; Harris, Brown, & Bifulcoa, 1986; Macksoud & Aber, 1996). A review by Dowdney (2000) identified moderating and mediating variables which lead some war-affected children to be at greater risk of post-traumatic stress reactions and internalizing symptoms following loss of a parent. These include: cause of parental death (e.g., traumatic death is more likely to lead to PTSD), gender of the child (i.e., females exhibit differentially greater rates of internalizing behaviors) and family functioning after parental loss (e.g., a less cohesive family structure predicts greater risk). Similar mechanisms are plausible in the present study whereby such a loss may limit the attachment figures and advocates a young person has in the post-conflict setting, further limiting the resources they can rely on to navigate life challenges. This interpretation is supported by the significant association we observed between parental death and community stigma.

Perceived community relationships also matter greatly. Perceived stigma was associated with greater odds of being in the high symptom or deteriorating trajectory. Stigma has previously been shown to mediate the relationship between “toxic” forms of violence exposure, such as the experience of rape, and depression symptoms in former child soldiers (Betancourt, Agnew-Blais, Gilman, Williams, & Ellis, 2010). Stigma and its negative mental health sequelae may also limit individuals’ access to other protective resources and opportunities such as employment and education (Link & Phelan, 2006; Njamnshi et al., 2009). In particular, stigma at the community level and abuse by family members is likely to lead to heightened social isolation, which easily gives way to feelings of hopelessness. In contrast, perceived community acceptance was significantly associated with improvement in symptoms which further highlight the vital influence of a child’s social environment in determining psychological adjustment following trauma and loss.

Overall, our study has sought to unpack the effects of specific risk factors for an identified mental health outcome (internalizing problems), using the identification of at-risk trajectory classes to achieve this end. The reasons for this are twofold. First, there is increasing evidence of differential relationships among trauma-related risk exposures and psychosocial outcomes, indicating the need to identify unique constellations of emotional and behavioral problems associated with specific war-related experiences (Layne et al., 2009; Shaw, 2003). Second, the developmental psychopathology perspective accounts for the dynamic interface between individuals and their environments and the way that this transaction shapes divergent developmental trajectories, including high-risk and resilient trajectories of internalizing problems (Duchesne et al., 2010; Sterba et al., 2007).

Our findings indicate that first of all, there is resilience among war-affected youth as indicated in the 89.1% of the sample that demonstrated either lower internalizing symptom levels or improvement over time compared to those who were highly symptomatic. For these and the 10.9% of the sample who demonstrate consistently poor or deteriorating trajectories of internalizing problems (and associated impairment) we are able to illuminate the specific factors that contribute to better or worse outcomes in order to inform intervention targets. Without such attention to the complexity of associations between conflict and post-conflict exposures and specific mental health outcomes, we are limited in our ability to identify those most at risk and develop appropriate intervention models.

Limitations

Study limitations must be noted. First of all, given limited surveillance of population mental health in this setting, no information is available on pre-war levels of internalizing problems or hardships. A larger and more regionally representative data set would improve our ability to differentiate between trajectory groups in multinomial logistic regressions, and additional time points of assessment would strengthen our ability to examine trajectories of internalizing problems over a longer time period. Further, the fact that not all independent variables included in the current analyses were assessed across all three time points limits our ability to interpret the directionality of associations between these measures and internalizing trajectories. The analyses of scales added after T1 was based on the premise that responses to measures administered only at T2 or T3 may serve as a proxy for responses at T1 had they been assessed at that time point. However, insofar as this assumption does not hold, the true directionality of these associations cannot be confirmed.

Our data are also limited to self-report accounts of war experiences and psychological adjustment. Information from multiple informants such as caregivers, significant others, and community members would provide more robust information, particularly in relating measures to the relevant ecological level (individual, family, community) of interest. This limitation is particularly important in the context of measures such as perceived stigma, which may overlap with internalizing insofar as individuals with greater internalizing problems may also have heightened sensitivity to negative encounters within the community.

It should also be recognized that descriptive statements such as “improvement over time” or “maintenance of low symptom scores” are relative to baseline scores within the sample and are therefore not absolute terms which can be extended to other populations and settings. The current findings should not be generalized beyond war-affected youth in Sierra Leone without further investigation of the longitudinal trajectories of psychological distress in new populations. This is reinforced by the fact that baseline data collection occurred following the war (i.e. there was no pre-war data collection), and as such there is no measure for what would be considered comparison levels of adversities in a non-conflict environment. Future investigations should also include similar analytic approaches applied to different outcomes such as post-traumatic stress reactions or externalizing problems to investigate whether the same or different sets of factors shape these trajectories (equifinality vs. multifinality).

Conclusions

Children in war are exposed to a wide range of conflict and post-conflict experiences, and these factors shape trajectories of psychological adjustment over time. The present study suggests a greater complexity in the post-war adjustment of war-affected children than has previously been depicted in the literature. It is noteworthy that, with time and the benefit of family and community support, most war-affected youth demonstrated resilient trajectories of internalizing problems despite the multiple traumas which characterize the experiences of former child soldiers and other war-affected youth. However, two trajectories representing those who maintain high levels of symptoms over time and those who show increases in symptoms over time (10.9% in total) are of particular concern. The war-affected youth belonging to these groups were characterized by being older or “overgrown” (likely missing critical opportunities to develop skills for education or employment), had experienced the death of a parent due to war, higher levels of stigma, and family abuse and neglect in the post-conflict setting.

The findings presented here are consistent with suggestions that broad-based public health and mental health promotion activities in post-emergency settings (e.g., family reunification programs and community acceptance campaigns) are well justified as a first line of response which should then be followed by targeted, evidence-based, and sustainable services models directed at those who continue to manifest elevated symptoms and functional impairments over time (Bolton & Betancourt, 2004; Miller & Rasmussen, 2010). It is important that the socio-ecological model that guided this study also inform intervention development and community sensitization so that both formal services and non-formal supports are robust across each layer of the social ecology. In particular, community efforts to reduce stigma, domestic violence and enhance family cohesion appear to be vital to support war-affected children over the long term. With a growing understanding of the dynamic array of issues contributing to the long-term psychosocial adjustment of war-affected youth, service providers and policy makers will be optimally prepared to develop effective and sustainable solutions to promote optimal adjustment, resilience and contributions to human capital in war-affected nations.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to the local research assistants who conducted interviews in Sierra Leone and our field-based project coordinators as well as our colleagues at the International Rescue Committee who collaborated in this data collection. In addition, we thank Sidney Atwood, who managed the data and supported the analyses. This study was funded by the United States Institute of Peace, USAID/DCOF, Grant #1K01MH077246-01A2 from the National Institute of Mental Health, the International Rescue Committee, the François-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights and the American Australian Association.

References

- Adjukovic M, Adjukovic D. Impact of displacement on psychological wellbeing of refugee children. International Review of Psychiatry. 1998;10:186–195. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad A. Posttraumatic stress among children in Kurdistan. Acta Paediatrica. 2008;97(7):884–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allwood MA, Bell-Dolan D, Husain SA. Children’s trauma and adjustment reactions to violent and nonviolent war experiences. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(4):450–457. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200204000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annan J, Brier M. The risk of return: Intimate partner violence in Northern Uganda’s armed conflict. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(1):152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barenbaum J, Ruchkin V, Schwab-Stone M. The psychological aspects of children exposed to war: Practice and policy initiatives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45(1):41–62. doi: 10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer CP, Klasen F, Adam H. Association of trauma and PTSD symptoms with openness to reconciliation and feelings of revenge among former Ugandan and Congolese child soldiers. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298(5):555–559. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:340–348. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS. Attending to the mental health of war-affected children: The need for longitudinal and developmental research perspectives. [Editorial] Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(4):323–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Agnew-Blais J, Gilman SE, Williams DR, Ellis BH. Past horrors, present struggles: the role of stigma in the association between war experiences and psychosocial adjustment among former child soldiers in Sierra Leone. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(1):17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Borisova II, Brennan RB, Williams TP, Whitfield TH, de la Soudiere M, Gilman SE. Sierra Leone’s former child soldiers: A follow-up study of psychosocial adjustment and community reintegration. Child Development. 2010;81(4):1077–1095. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Brennan RT, Rubin-Smith J, Fitzmaurice GM, Gilman SE. Sierra Leone’s former child soldiers: a longitudinal study of risk, protective factors, and mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(6):606–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Khan KT. The mental health of children affected by armed conflict: Protective processes and pathways to resilience. International Review of Psychiatry. 2008;20(3):317–328. doi: 10.1080/09540260802090363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Meyers-Ohki SE, Charrow AP, Tol WA. Interventions for children affected by war: An ecological perspective on psychosocial support and mental health care. American Journal of Community Psychology. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0b013e318283bf8f. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Simmons S, Borisova I, Brewer SE, Iweala U, de la Soudiere M. High hopes, grim reality: Reintegration and the education of former child soldiers in Sierra Leone. Comparative Education Review. 2008;52(4):565–587. doi: 10.1086/591298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P, Betancourt TS. Mental health in postwar Afghanistan. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292(5):626–628. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.5.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. The Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The bioecological theory of human development. In: Bronfenbrenner U, editor. Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development. Sage Publications Ltd; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2005. pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control [Retrieved October 30, 2006];State and local youth risk behavior survey. 2005 from http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/pdfs/2005highschoolquestionaire.pdf.

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch F. Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:597–600. [Google Scholar]

- Denov M. Girl soldiers and human rights: Lessons from Angola, Mozambique, Sierra Leone and Northern Uganda. International Journal of Human Rights. 2007;12(5):813–836. [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Boxer P, Huesmann LR, Shikaki K, Landau S, Gvirsman SD, Ginges J. Exposure to conflict and violence across contexts: relations to adjustment among Palestinian children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39(1) doi: 10.1080/15374410903401153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchesne S, Larose S, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE. Trajectories of anxiety in a population sample of children: clarifying the role of children’s behavioral characteristics and maternal parenting. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22(2):361–373. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durakovic-Belko E, Kulenovic A, Dapic R. Determinants of posttraumatic adjustment in adolescents from Sarajevo who experienced war. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;59(1):27–40. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyregrov A, Gjestad R, Raundalen M. Children exposed to warfare: a longitudinal study. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2002;15(1):59–68. doi: 10.1023/A:1014335312219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhood L, Zurayk H, Chaya M, Saadeh F, Meshefedjian G, Sidani T. The impact of war on the physical and mental health of the family: The Lebanese experience. Social Science & Medicine. 1993;36:1555–1567. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90344-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore FM, Bloem PJN, Patton GC, Ferguson J, Joseph V, Coffey C, Mathers CD. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10-24 years: A systematic analysis. The Lancet. 2011;377:2093–2102. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60512-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorst-Unsworth C, Goldenberg E. Psychological sequelae of torture and organized violence suffered by refugees from Iraq: Trauma-related factors compared with social factors in exile. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;172(1):90–94. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris T, Brown GW, Bifulcoa A. Loss of parent in childhood and adult psychiatric disorder: the role of lack of adequate parental care. Psychological Medicine. 1986;16:641–659. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700010394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Rogers W, Spritzer K. Functioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illnesses. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52(1):11–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950130011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ILO-UNDP for the Executive Representative of the Secretary-General, & UNIPSIL Support to the Government of the Republic of Sierra Leone by the International Community: Joint initiative for employment promotion in the Republic of Sierra Leone. 2010.

- Jacob KS, Sharan P, Mirza, Garrido-Cumbrera IM, Seedat S, Mari JJ, Saxena S. Mental health systems in countries: where are we now? The Lancet. 2007;370:1061–1077. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joussemet M, Vitaro F, Barker ED, Cote S, Nagin DS, Zoccolillo M, Tremblay RE. Controlling parenting and physical aggression during elementary school. Child Development. 2008;79(2):411–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzie JD, Sack W, Angell R, Clarke G, Ben R. A three-year follow-up of Cambodian young people traumatized as children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1989;28(4):501–504. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198907000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzie JD, Sack WH, Angell RH, Manson S, Rath B. The psychiatric effects of massive trauma on Cambodian children: I. The children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1986;25:370–376. [Google Scholar]

- Klasen F, Oettingen G, Daniels J, Adam H. Multiple trauma and mental health in former Ugandan child soldiers. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23:573–581. doi: 10.1002/jts.20557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA. In: Recommendations to promote psychosocial well-being of children associated with armed forces and armed groups (CAAFAG) in Nepal. Nepal TPOT, editor. UNICEF; Kathmandu, Nepal: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA. Traditional healing and the social fabric: Implications for psychosocial interventions with child soldiers. Paper presented at the Society for Psychological Anthropology Annual Meeting; Asilomar, California. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Jordans MJ, Tol WA, Speckman RA, Maharjan SM, Worthman CM, Komproe IH. Comparison of mental health between former child soldiers and children never conscripted by armed groups in Nepal. Journal of American Medical Association. 2008;300(6):691–702. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laor N, Wolmer L, Cohen DJ. Mothers’ functioning and children’s symptoms 5 years after a SCUD missile attack. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(7):1020–1026. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.7.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layne CM, Beck CJ, Rimmasch H, Southwick JS, Moreno MA, Hobfoll SE. Promoting “resilient” posttraumatic adjustment in childhood and beyond: “Unpacking” life events, adjustment trajectories, resources, and interventions. In: Brom D, Pat-Horenczyk R, Ford J, editors. Treating traumatized children: Risk, resilience, and recovery. Routledge; New York: 2009. pp. 13–47. [Google Scholar]

- Layne CM, Olsen JA, Baker A, Legerski JP, Isakson B, Pas̆alić A. Unpacking trauma exposure risk factors and differential pathways of influence: Predicting post-war mental distress in Bosnian adolescents. Child Development. 2010;81(4):1053–1076. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layne CM, Stuvland R, Saltzman W, Djapo N, Pynoos RS. Adolescent post war adversities scale. 1999. Unpublished instrument.

- Leadbeater BJ, Hoglund WL. The effects of peer victimization and physical aggression on changes in internalizing from first to third grade. Child Development. 2009;80(3):843–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater BJ, Schellenbach CJ, Maton KI, Dodgen DW. Research and policy for building strengths: Processes and contexts of individual, family and community development. In: Maton KI, Schellenbach CJ, Leadbeater BJ, Solarz AL, editors. Investing in children, youth, families, and communities: Strengths-based research and policy. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2004. pp. 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Stigma and its public health implications. Lancet. 2006;367(9509):528–529. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. John Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS. Vulnerability and resilience: A study of high-risk adolescents. Child Development. 1991;62(3):600. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machel G. Report of the expert of the Secretary-General, submitted pursuant to UN General Assembly resolution 48/157. United Nations; New York: 1996. Impact of armed conflict on children. [Google Scholar]

- Macksoud MS, Aber JL. The war experiences and psychosocial development of children in Lebanon. Child Development. 1996;67(1):70–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMullin C, Loughry M. Investigating psychosocial adjustment of former child soldiers in Sierra Leone and Uganda. Journal of Refugee Studies. 2004;17(4):460–472. [Google Scholar]

- Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Medicine. 2006;3(11):2011–2030. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Omidian P, Rasmussen A, Yaqubi A, Daudzai H. Daily stressors, war experiences, and mental health in Afghanistan. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2008;45(4) doi: 10.1177/1363461508100785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Rasmussen A. Mental health and armed conflict: The importance of distinguishing between war exposure and other sources of adversity: A response to Neuner. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71:1385–1389. [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Rasmussen A. War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: Bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgos D, Worden JW, Gupta L. Psychosocial effects of war experiences among displaced children in southern Darfur. Omega (Westport) 2007;56(3):229–253. doi: 10.2190/om.56.3.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6th ed Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS. Group-based modeling of development. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS, Tremblay RE. Analyzing developmental trajectories of distinct but related behaviors: a group-based method. Psychological Methods. 2001;6(1):18–34. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman DA. Longitudinal modeling with randomly and systematically missing data: A simulation of ad hoc, maximum likelihood, and multiple imputation techniques. Organizational Research Methods. 2003;6(3):328–362. [Google Scholar]

- Njamnshi AK, Tabah EN, Yepnjio FN, Angwafor SA, Dema F, Fonsah JY, Muna WF. General public awareness, perceptions, and attitudes with respect to epilepsy in the Akwaya Health District, South-West Region, Cameroon. Epilepsy Behavior. 2009;15(2):179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.03.013. doi: S1525-5050(09)00157-7 [pii] 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panter-Brick C, Goodman A, Tol WA, Eggerman M. Mental health and childhood adversities: A longitudinal study of school children in Kabul, Afghanistan. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50:349–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Araya R, Chatterjee S, Chisholm D, Cohen A, De Silva M, van Ommeren M. Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet. 2007;370(9591):991–1005. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, McGorry P. Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. The Lancet. 2007;369:1302–1313. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham PN, Vinck P, Stover E. Returning home: forced conscription, reintegration, and mental health status of former abductees of the Lord’s Resistance Army in northern Uganda. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen A, Nguyen L, Wilkinson J, Vundla S, Raghavan S, Miller KE, Keller AS. Rates and impact of trauma and current stressors among Darfuri refugees in Eastern Chad. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80:227–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder K, Lynch K, Nagin DS. Modeling uncertainty in latent class membership: a case study in criminology. Journal of American Statistical Association. 1999;94:766–776. [Google Scholar]

- Sack WH, Clarke G, Him C, Dickason D, Goff B, Lanham K, Kinzie JD. A 6-year follow-up study of Cambodian refugee adolescents traumatized as children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32(2):431–437. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199303000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277(5328):918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc . SAS. Version 9.2 Cary, North Carolina: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J. Children exposed to war/terrorism. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6(4):237–246. doi: 10.1023/b:ccfp.0000006291.10180.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterba SK, Bauer DJ. Matching method with theory in person-oriented developmental psychopathology research. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22(02):239–254. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterba SK, Prinstein MJ, Cox MJ. Trajectories of internalizing problems across childhood: heterogeneity, external validity, and gender differences. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19(2):345–366. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thabet AA, Abed Y, Vostanis P. Comorbidity of PTSD and depression among refugee children during war conflict. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2004;45(3):533–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . Sierra Leone: Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2005. United Nations Children’s Fund; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . State of the World’s Children 2008. UNICEF; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ommeren M, Sharma B, Thapa S, Makaju R, Prasain D, Bhattarai R, De Jong J. Preparing instruments for transcultural research: Use of the translation monitoring form with Nepali-speaking Bhutanese refugees. Transcultural Psychiatry. 1999;36(3):285. [Google Scholar]

- Weine S, Becker DF, McGlashan TH, Vojvoda D, Hartman S, Robbins JP. Adolescent survivors of ‘ethnic cleansing’: Observations on the first year in America. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:1153–1159. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199509000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical & mental health: Socioeconomic status, stress, and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2(3):335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. WHO Press; Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]