Abstract

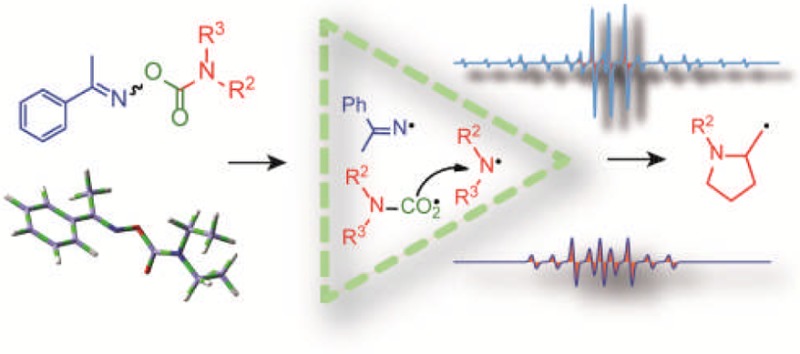

A set of oxime carbamates having N-alkyl and N,N-dialkyl substituents were prepared via carbonyldiimidazole intermediates. It was shown by EPR spectroscopy that they underwent clean homolysis of their N–O bonds upon UV photolysis. During photolysis of acetophenone O-allylcarbamoyl oxime, the corresponding oxazolidin-2-onylmethyl radical was detected by EPR spectroscopy, providing the first evidence that N-monosubstituted carbamoyloxyl radicals can hold their structural integrity. N,N-Disubstituted carbamoyloxyl radicals dissociated rapidly at the lowest accessible temperatures. Above room temperature, both types of oxime carbamate acted as selective new precursors for aminyl and iminyl radicals. Rate parameters were measured for 5-exo cyclization of N-benzyl-N-pent-4-enylaminyl radicals; the rate constant was smaller than for C-centered and O-centered analogues. Oxime carbamates derived from the volatile diethylamine afforded aryliminyl radicals that proved convenient for phenanthridine preparations.

Introduction

Oxime carbamates (O-carbamoyl oximes) have been known for a considerable time for their antimicrobial activity1 and as inhibitors of various enzymes.2 End-product analyses of complex mixtures obtained from photolyses of a few carbamate pesticides were reported,3 but the notion of oxime carbamates as selective radical precursors had not been tested. We recently discovered that oxime carbonates efficiently dissociate upon photolysis to generate iminyl and alkoxycarbonyloxyl radicals. These oxime derivatives proved to be valuable precursors for clean syntheses of several types of heterocycles.4 In view of the structural similarity of oxime carbamates [ArC(R1)=N–OC(O)NR2R3], we conjectured that their N–O bonds would also break upon photolysis. In this way, access to iminyl radicals and the much more exotic carbamoyloxyl radicals might be gained. The latter radicals were essentially unknown. Ingold and co-workers’ attempts to observe them by laser flash photolysis of tert-butyl percarbamates [RR′NC(O)OOBu-t] disclosed only aminyls (RR′N•),5 as did Newcomb’s study of N-hydroxypyridine-2-thione carbamates.6 No other reports of carbamoyloxyl radicals have appeared. They were expected to dissociate rapidly to CO2 and aminyl radicals, so there were question marks concerning their structural integrity.

Suitable tuning of the oxime carbamate structure might enable individual members of this triad of radicals (iminyl, carbamoyloxyl, aminyl) to be highlighted and examined. A distinct advantage of oxime carbamate precursors would be the opportunity to search for evidence of carbamoyloxyl radicals at much lower temperatures using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. We carried out an exploratory density functional theory (DFT) study of the reactivity of prototypical carbamoyloxyls. We also prepared a set of model oxime carbamates (see Scheme 1) and investigated the radicals released by each upon photolysis. In this article, we show that by an appropriate choice of substituents the rare carbamoyloxyl radicals could indeed be generated. They were cleanly transformed to aminyl radicals at higher temperatures, thus providing a new and promising source of these intermediates. Information about the cyclization behavior of both carbamoyloxyl and aminyl radicals was obtained. Furthermore, with a different substitution pattern, oxime carbamates could be adapted for release of iminyl radicals and hence for subsequent preparations of N-heterocycles.

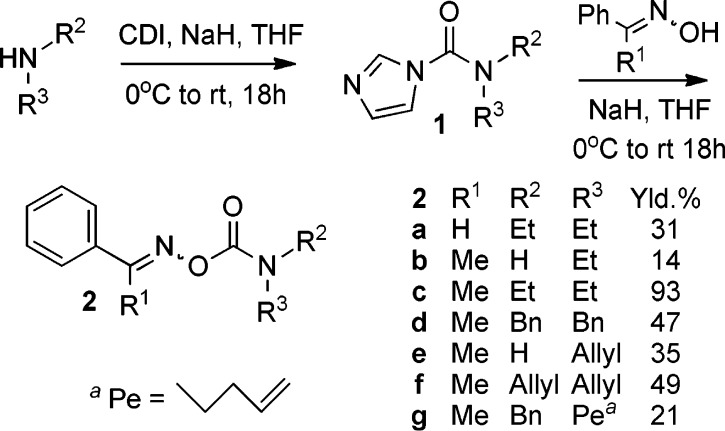

Scheme 1. CDI-Mediated Preparations of Oxime Carbamates.

Results and Discussion

DFT Computations on Carbamoyloxyl and Related Radicals

Would carbamoyloxyl radicals be too fragile to take part in chemical reactions or to be observed spectroscopically? To obtain theoretical insight into how the rate of CO2 loss responded to carbamoyloxyl structure, we carried out DFT computations7 on the model radicals shown in Table 1. Previous calculations on the structurally related alkoxycarbonyloxyl radicals4c had shown that for these species the B3PW91 functional8 and the M06-2X hybrid metafunctional9 gave energies seriously at odds with experiment. Similarly, second-order Møller–Plesset perturbation theory (MP2) with the 6-311+G(2d,p) basis set delivered activation energies that greatly exceeded experiment. The best results were obtained using the B3LYP functional. For our study of carbamoyloxyls, we therefore employed the standard UB3LYP functional with the correlation-consistent polarized triple-ζ cc-pvtz basis set (method A),10 and we also employed the CBS-QB3 level of theory (method B).11

Table 1. DFT-Computed Activation Energies (ΔE298⧧), Reaction Enthalpies (ΔH298), and Reaction Free Energies (ΔG298) for CO2 Loss from Z–CO2• Radicals at 298 Ka.

| radical | methodb | ΔE298⧧ | ΔH298 | ΔG298 | Eexpt⧧ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Et2N–CO2• | A | 1.3 | –8.8 | –20.2 | – |

| B | 0.7 | –5.5 | –16.8 | ||

| EtNH–CO2• | A | 6.5 | –5.5 | –15.6 | – |

| B | 7.4 | –4.7 | –14.7 | ||

| NH2–CO2• | A | 11.6 | –1.2 | –9.5 | – |

| B | 11.8 | –3.5 | –12.1 | ||

| EtO–CO2• | A | 11.5 | –7.8 | –18.9 | ∼13c |

| B | 16.1 | –3.9 | –13.8 | ||

| Et–CO2• | A | [0.4]d | –16.5 | –28.6 | ∼1.7e |

| B | –d | –14.6 | –24.8 |

Energies in kcal mol–1 are reported.

Method A: UB3LYP/cc-pvtz level including corrections to 298 K. Method B: CBS-QB3 level.

Value for primary RCH2OC(O)O• radicals (see ref (4b)).

A well-defined transition state was not found with the cc-pvtz basis set or at the CBS-QB3 level. A ΔE298⧧ value of 0.44 kcal mol–1 was obtained for a transition state located with the 6-31G(d) basis set.

See ref (12).

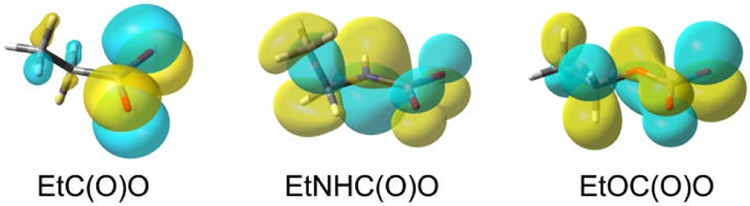

Although the magnitudes of the values differ somewhat depending on the computational level, two remarkable trends can be clearly discerned. First, for the carbamoyloxyl radicals, the ΔE298⧧ barriers increased strongly and the reactions became less exothermic as the number of H atoms attached to nitrogen increased. Second, for the series Z–CO2•, the barriers increased significantly as the leading atom of Z moved across the first row of the periodic table from Z = Et to EtHN to EtO. The computed structures and singly occupied molecular orbitals (SOMOs) (Figure 1) showed that the SOMO of EtCO2• is confined mainly to the CO2 unit, whereas the EtNHCO2• and EtOCO2• radicals are alike in that their SOMOs are delocalized to the adjacent heteroatoms and to the alkyl substituents. This was a hint that monoalkyl EtNHCO2• radicals might behave like EtOCO2• radicals in losing CO2 comparatively slowly, rather than extruding CO2 essentially instantly as RCH2CO2• radicals do.

Figure 1.

DFT-computed SOMOs of Z–CO2• radicals.

For RCO2•12 and ROCO2•, the computed barriers were in reasonable agreement with the experimental activation energies (Eexpt⧧) (Table 1). This lent credibility to the predicted trends. The computed intermediate properties of EtNHCO2• and its substantial ΔE298 suggested that monoalkyl-substituted carbamoyloxyls would have finite lifetimes. This implied that adducts or cycloadducts might be detectible at the low temperatures accessible in EPR spectroscopy. On the other hand, the very low ΔE298⧧, high exothemicity, and strongly negative ΔG298 for Et2NCO2• implied that photolyses of N,N-dialkyl oxime carbamates would directly release dialkylaminyls (with iminyls) in the temperature/time zone accessible to EPR spectroscopy. To put these conclusions to the test, we prepared a set of model oxime carbamates (Scheme 1).

Preparation of Oxime Carbamates

Previous preparations of oxime carbamates have involved treatment of oximes with either phosgene and then an amine or with an isocyanate.13,14 Some organic carbamates have been made via carbonyldiimidazole (CDI) derivatives of alcohols.5,15 We used this reagent successfully in preparations of oxime carbonates.4 Laboratory use of phosgene can be avoided by using CDI, so we tried the analogous route to oxime carbamates 2 via intermediates 1 (Scheme 1). Although the method succeeded with both primary and secondary amines, the unoptimized yields were rather variable. The carbamates from primary amines were difficult to purify and degraded comparatively quickly.

EPR Spectroscopic Study of Oxime Carbamate Photolysis

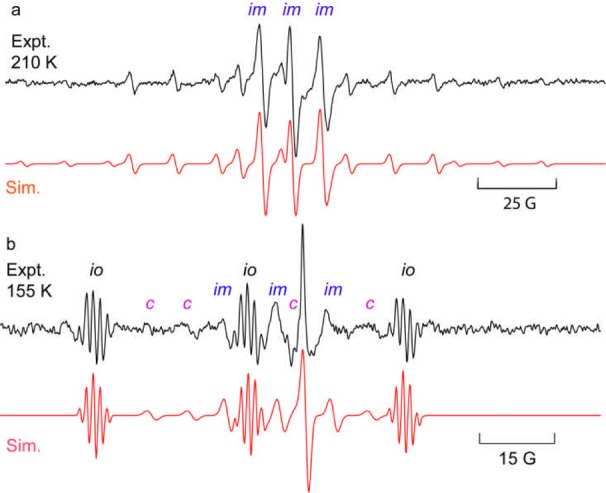

The photolytic reactions of oxime carbamates 2a–g were first investigated in solution by 9 GHz EPR spectroscopy. Deaerated samples of each oxime carbamate, plus 1 equiv of 4-methoxyacetophenone (MAP) as a photosensitizer, in t-BuPh or cyclopropane solvent were irradiated with unfiltered UV light from a medium-pressure Hg lamp directly in the spectrometer resonant cavity. The spectrum obtained with diallyl precursor 2f (Figure 2a) revealed the iminyl radical PhCMe=N• (Im) together with a second radical displaying a pentet of 1:1:1 triplets structure. These EPR parameters were similar to literature data for (allyl)2N• radicals (6f).16 The measured [6f]/[Im] concentration ratio was 0.92 ± 0.1 at 210 K (see Figure 3a). The fact that this was close to 1.0 indicated that decarboxylation of 3f to give 6f (Scheme 2) must be fast at 210 K.

Figure 2.

EPR spectra from sensitized photolyses of oxime carbamates (experimental spectra are shown in black and simulations in red): (a) diallyl precursor 2f in t-BuPh at 210 K; (b) monoallyl precursor 2e in cyclopropane at 155 K. [im = iminyl radical, io = iminoxyl radical, c = cyclized radical 4e].

Figure 3.

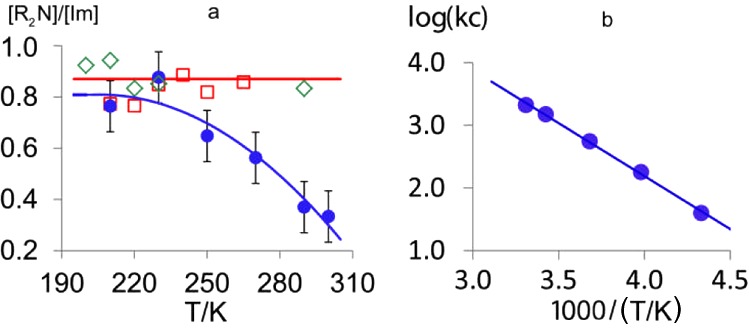

(a) Temperature dependence of [6]/[Im] ratios: blue ●, PeBnN• (6g); red □, Bn2N• (6d); green ◇, (allyl)2N• (6f). (b) Arrhenius plot of kc for 6g.

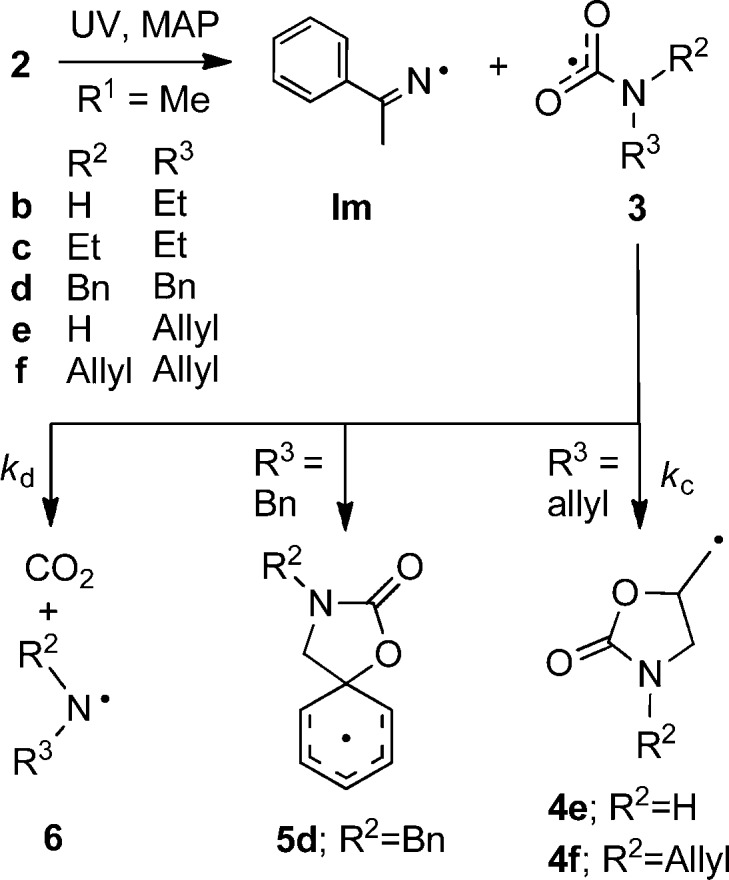

Scheme 2. Reaction Channels for Carbamoyloxyl Radicals.

By analogy with alkoxycarbonyloxyl radicals, the carbamoyloxyl radical 3f derived from 2f was expected to undergo rapid ring closure to give oxazolidin-2-onyl-methyl radical 4f. However, 4f was not observed over the temperature range 160–270 K, which supports the conclusion that N,N-diallyl radical 3f loses CO2 rapidly. The EPR spectra observed upon photolysis of N,N-diethyl precursor 2c revealed that it too yielded Im and Et2N• radicals throughout the accessible temperature range [see the Supporting Information (SI)]. Thus, N,N-diethylcarbamoyloxyl radical 3c also dissociates extremely rapidly.

The best spectrum obtained upon photolysis of the monoallyl precursor 2e at 155 K (Figure 2b) showed Im and some iminoxyl (io) impurity.17 At higher temperatures, only the Im (and io) were visible (see the SI). Monoalkylaminyl radicals RHN• are EPR-silent in solution,16 and therefore, the CO2 loss reaction of 3e could not be monitored by observation of (allyl)HN•. However, Figure 2b shows weak signals (c) that were simulated with a radical having g = 2.0023, a(2Hα) = 22.0 G, and a(Hβ) = 8.5 G. These EPR parameters are close to those of structurally similar 1,3-dioxolan-2-onylmethyl radicals,4 and we attribute them to oxazolidin-2-onylmethyl radical 4e.

If this identification is correct, it is evidence that N-monoalkyl-substituted carbamoyloxyls retain their structural integrity at 155 K. Radical 4e was not observed in spectra at higher temperatures, so dissociation evidently sets in at T ≳ 170 K. An estimate of the activation energy for CO2 loss from 3e (Ed⧧) was obtained from the empirical relationship for the activation energies of β-scission reactions and EPR temperature data.18 A midpoint temperature of 170 K yielded Ed ≈ 8 kcal mol–1. This compares favorably with the DFT-computed ΔE298⧧ values of 6.5 and 7.4 kcal mol–1 for EtNHCO2• (Table 1), particularly when the known propensity of the B3LYP functional to underestimate barrier heights19 is taken into account. The other monoalkyl precursor 2b was poorly soluble in cyclopropane, so only broad, ill-defined signals were observed in this solvent. At T > 210 K in t-BuPh solvent, only Im (and impurity io) could be detected.

The dibenzyl precursor 2d yielded EPR spectra of Bn2N• (6d) and Im. Cyclohexadienyl radical 5d, which would have resulted from spiro cyclization of 3d onto the phenyl ring, was not detected. The [6d]/[Im] ratio was close to 1.0 over the accessible temperature range (Figure 3a). It was therefore evident that 3d dissociates very rapidly. We conclude that all of the N,N-dialkyl precursors act as clean sources of aminyl and iminyl radicals.

Precursor 2g with a pentenyl (Pe) chain was prepared for use in examining aminyl radical cyclization. Upon photolysis at temperatures in the range 210–260 K, the EPR spectrum revealed a mixture of Im and a second radical having the following EPR parameters: g = 2.0048, a(N) = 14.2 G, a(2H) = 35.4 G, and a(2H) = 36.9 G at 230 K. By comparison with data for other dialkylaminyl radicals, this species was easily identified as the disubstituted aminyl 6g (Scheme 3; also see the SI).

Scheme 3. Ring Closure of Pentenyl-Substituted Aminyl 6g.

The ring-closed pyrrolidinylmethyl radical 7g was not observed over the accessible temperature range up to 300 K. However, as the temperature was increased, the [6g]/[Im] ratio steadily decreased (Figure 3a), in contrast to the essentially invariant [R2N•]/[Im] ratios obtained with the dibenzyl (2d) and diallyl (2f) precursors, where the R2N• products were not capable of cyclization. We interpret the decreasing [6g]/[Im] ratio to result from the onset of 5-exo ring closure of 6g.20 An estimate of the cyclization rate constant (kc) for 6g could still be obtained because the Im radical acted as a reference. Equimolar quantities of Im and 6g are formed upon homolysis of 2g, and hence, [Im] = [6g] + [7g]. The mechanism is shown in Scheme 3, including termination processes for Im, 6g, and 7g radicals. With the steady-state approximation, it can easily be shown that21

| 1 |

under the assumption that all of the termination reactions are diffusion-controlled (because all of the radicals are small) and have the same rate constant, 2kt. Values of kc were derived from eq 1 using radical concentrations determined from the EPR spectra in the T > 210 K region. Under the assumption that the termination reactions are diffusion-controlled, the well-established 2kt Arrhenius parameters for t-Bu• radicals derived by Fischer22 [log At = 11.63 M–1 s–1, Et = 2.25 kcal mol–1], corrected for solvent viscosity as described previously,23 could be used for 2kt without introducing serious errors. A good Arrhenius plot of kc was obtained (Figure 3b). The temperature range was narrow and the data were scattered, so the log(Ac/s–1) value of 9.0 ± 1.5 derived by linear regression is not reliable. Most radical cyclizations have log(Ac/s–1) ≈ 10.5.24 For consistency in comparing our data with related kinetic parameters, this value was assumed, leading to the following expression for kc:

| 2 |

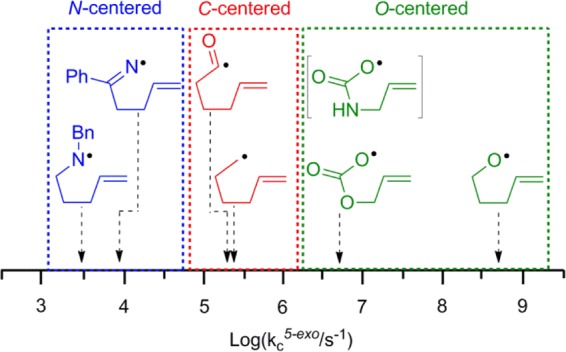

θ = 2.303RT/1000. This gives kc = 3 × 103 s–1 for 6g at 300 K, which compares well25 with the values of 5 × 104 and 1 × 104 s–1 for 5-exo ring closures of N-butyl-N-pentenylaminyl and N-butyl-N-(2-phenylcyclopropyl)pentenylaminyl, respectively, at 50 °C as reported by Newcomb and co-workers.26 Clearly, N,N-dialkylaminyl radicals cyclize nearly 2 orders of magnitude more slowly at 300 K than archetypal C-centered hex-5-enyl radicals, for which kc = 2.5 × 105 s–1.27

Preparative-scale photolyses of 2g in PhCF3 and PhMe showed complex product mixtures. GC–MS analysis pointed to the termination products Im2 and Im–NBnPe along with the ring-closure products 1-benzyl-2-methylpyrrolidine and 1-benzyl-2-methylenepyrrolidine; attempts to isolate these for confirmation were not successful. The mechanism in Scheme 3 was supported, but as might be expected under the nonchain conditions, cyclization competed poorly with terminations.

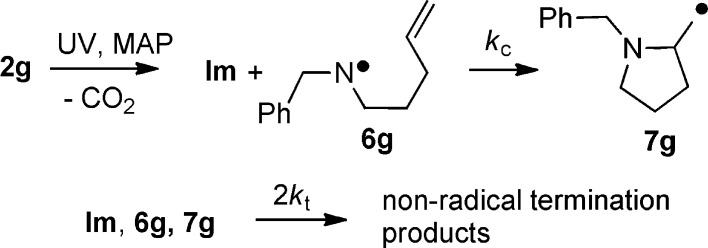

Iminyl Radical Cyclization and Phenanthridine Preparation

Making the aminyl moiety small and volatile might allow oxime carbamates to be adapted for selective production of N-heterocycles derived from their iminyl portions. To test this possibility, diethylaminyl carbamate 8a was prepared. Indeed we found that 3-methoxy-6-methylphenanthridine (10) was obtained in 60% yield from photolysis of 8a at room temperature in benzotrifluoride with MAP as a photosensitizer. The reaction also worked well (61%) in the absence of MAP, which is a significant advance because the photosensitizer can be difficult to remove during product purification. The mechanism probably involves generation of iminyl radical 8Im, which cyclizes onto the adjacent aromatic ring to produce cyclohexadienyl radical 9 (Scheme 4). Radical 9 readily rearomatizes to 10 either by H-atom transfer to another radical or by electron transfer with production of the corresponding cyclohexadienyl cation and subsequent proton loss.28 In support of this, iminyl radical 8Im was observed when 8a was UV-irradiated in the EPR spectrometer. Not surprisingly, the ring-closed radical 9 was not detected because cyclization occurs at T > 300 K, where the spectra are weak.

Scheme 4. Reactions of Biphenyl Oxime-Derived Carbamates.

Isolated yield.

1H NMR yield calculated using CH2Br2 as an internal standard.

An intriguing process took place during attempts to prepare the analogous oxime carbamate 13 from N-benzylpent-4-en-1-amine. When the CDI precursor 12 and oxime 11 were treated with NaH in the standard way, instead of the expected 13, phenanthridine 10 was isolated in 44% yield. The mechanism probably does not involve radical intermediates. A sequence of electrocyclic rearrangements of 13 can readily be envisaged.29

Conclusions

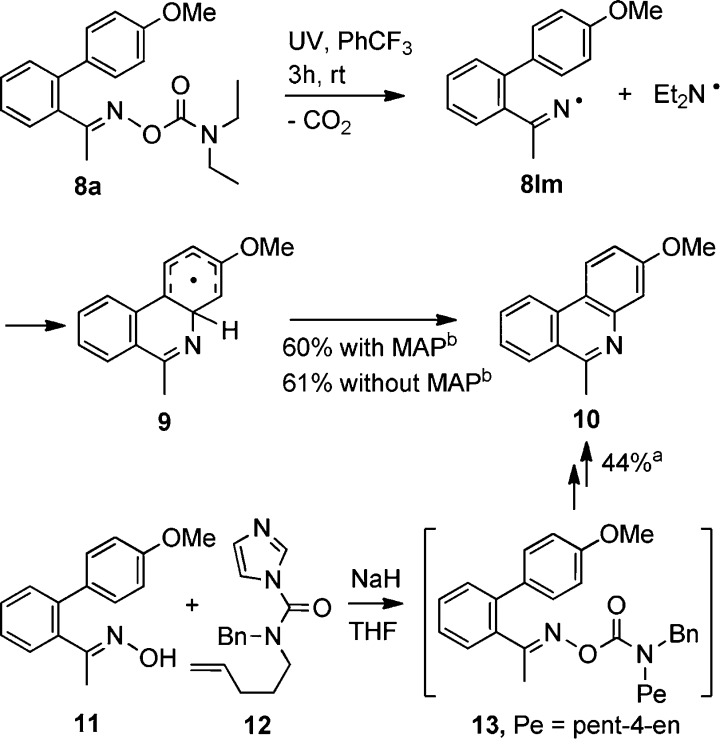

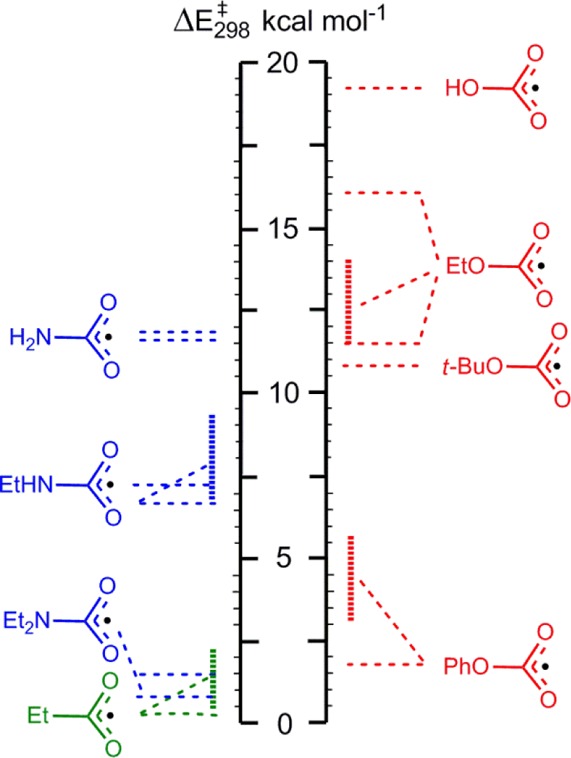

Oxime carbamates were shown reliably to dissociate photolytically by scission of their N–O bonds. The resulting iminyl radicals were directly monitored by EPR spectroscopy. Spectroscopic evidence was obtained for the formation of oxazolidin-2-onylmethyl radical 4e at 155 K by cyclization of N-allylcarbamoyloxyl radical 3e. N,N-Dialkylcarbamoyl radicals, on the other hand, dissociated rapidly even at 155 K, yielding dialkylaminyls. These observations confirmed our theoretical prediction that the rates of decarboxylation of carbamoyloxyls would increase as the number of N-alkyl substituents increased. The experimental and computed activation energies for dissociation of carbamoyloxyls, alkoxycarbonyloxyls,4,30 and acyl radicals12 are compared in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Comparison of activation energies for CO2 loss from Z–CO2• radicals. Horizontal dashed lines point to DFT-computed values; hashed areas represent experimental data.

Figure 4 shows a considerable degree of consonance between theory and experiment. Also in agreement with theory, the rates of CO2 loss from Z–C(=O)O• radicals decrease as the leading atom of Z changes from C to N to O. Of the ROC(O)O series, the member having R = Ph dissociates most rapidly because of the resonance stabilization of the phenoxyl radical. Of course, the corresponding N-arylcarbamoyloxyl radicals (Ph2NCO2• and PhHNCO2•) are also expected to dissociate with great rapidity, if they have any finite lifetime at all. The parent carbamic acid radical (H2NCO2•) was projected to lose CO2 comparatively slowly. Figure 4 indicates that this would occur at about the same rate as for RCH2OC(O)O• radicals, which dissociate slowly at room temperature. H2NCO2• dissociation would be rapid at higher temperatures. The literature contains virtually no information about this radical apart from a study of some protonated forms.31 However, carbamic acid itself is well-known to be unstable above room temperature and to dissociate to carbon dioxide and ammonia. H2NCO2• was not accessible via our oxime carbamate route to assess these points.

At T > 200 K, both N-alkyl- and N,N-dialkyloxime carbamates were found to be new and effective precursors for aminyl radicals. By this means we determined that pent-4-enylaminyl radical 6g undergoes 5-exo cyclization comparatively slowly. The rate constants for 5-exo cyclization [kc5-exo(300 K)] for a set of model hex-5-enyl-type radicals having N, C, and O centers, including 6g, 3e, hex-5-enyl,27 hex-5-enoyl,32 allyloxycarbonyloxyl,4b and pent-4-enyloxyl,33 are ranked in Figure 5. The rate constants span 5 orders of magnitude and fall neatly into three areas. The N-centered radicals, including aminyl and iminyl, cyclize the slowest. The C-centered radicals, including alkenyl and acyl, cyclize at intermediate rates, and the O-centered ones cyclize fastest. The rates are clearly not directly related to the electronegativities of the initial radical centers but probably reflect the reaction exothermicities.33

Figure 5.

Hierarchy of 5-exo cyclization rate constants for hex-5-enyl-type radicals at 300 K.

Precursors of the biphenylethanone O-dialkylcarbamoyl oxime type (e.g., 8a), which contain volatile amine moieties, were convenient starting points for phenanthridine syntheses. Other routes to this ring system include anionic processes,34 Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions,35 and radical-mediated processes;4c,36 the latter two approaches have recently been reviewed.37 Our strategy is promising for preparations of this and other types of N-heterocycles in terms of ease of precursor preparation, mild and metal-free experimental procedure, and easy workup.

Acknowledgments

We thank the EPSRC (Grant EP/I003479/1) and EaStCHEM for funding, the EPSRC U.K. National Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Service at the University of Manchester, and the EPSRC National Mass Spectrometry Service in Swansea. We are grateful to Dr. Herbert Fruchtl for help with the computing and Annika Eisenschmidt for data collection.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental procedures, full spectroscopic data for new compounds, sample EPR spectra and kinetic data, DFT-computed ground-state and transition-state structures, and complete ref (7) (as SI ref 3). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Present Address

† R.T.M.: University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, U.K.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- For example, see:; a Kurtz A. P.; Durden J. A. Jr.; Sousa A. A.; Weiden M. H. J. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1987, 35, 106–114. [Google Scholar]; b Kurtz A. P.; Durden J. A. Jr. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1987, 35, 115–121. [Google Scholar]; c Raza S. K.; Khullar A.; Jaiswal D. K. Orient. J. Chem. 1994, 10, 253–258. [Google Scholar]; d Patil S. S.; Jadhav S. D.; Deshmukh M. B. J. Chem. Sci. 2012, 124, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar]

- a Gattinoni S.; De Simone C.; Dallavalle S.; Fezza F.; Nannei R.; Battista N.; Minetti P.; Quattrociocchi G.; Caprioli A.; Borsini F.; Cabri W.; Penco S.; Merlini L.; Maccarrone M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 4406–4411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sit S. Y.; Conway C. M.; Xie K.; Bertekap R.; Bourin C.; Burris K. D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 1272–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Freeman P. K.; McCarthy K. D. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1984, 32, 873–877. [Google Scholar]; b Freeman P. K.; Ndip E. M. N. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1984, 32, 877–881. [Google Scholar]

- a McBurney R. T.; Slawin A. M. Z.; Smart L. A.; Yu Y.; Walton J. C. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 7974–7976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b McBurney R. T.; Harper A. D.; Slawin A. M. Z.; Walton J. C. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 3436–3444. [Google Scholar]; c McBurney R. T.; Eisenschmidt A.; Slawin A. M. Z.; Walton J. C. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 2028–2035. [Google Scholar]

- Chateauneuf J.; Lusztyk J.; Maillard B.; Ingold K. U. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 6727–6731. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb M.; Park S.-U.; Kaplan J.; Marquardt D. J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985, 26, 5651–5654. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; et al. Gaussian 09, revision A.02; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2009.

- Perdew J. P.; Burke K.; Wang Y. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 16533–16539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Truhlar D. G. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 157–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A. K.; van Mourik T.; Dunning T. H. Jr. J. Mol. Struct.: THEOCHEM 1996, 388, 339–349. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery J. A. Jr.; Frisch M. J.; Ochterski J. W.; Petersson G. A. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 2822–2827. [Google Scholar]

- Skakovskii E. D.; Stankevich A. I.; Lamotkin S. A.; Tychinskaya L. Yu.; Rykov S. V. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2001, 71, 614–622. [Google Scholar]

- For a review, see:; Chaturvedi D. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 15–45. [Google Scholar]

- a Letsinger R. L.; Kornet M. J.; Mahadevan V.; Jerina D. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 5163–5165. [Google Scholar]; b Dalton D. R.; Foley H. G. J. Org. Chem. 1973, 38, 4200–4203. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer W. Synthesis 2002, 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- a Danen W. C.; Kensler T. T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 5235–5237. [Google Scholar]; b Davies A. G.; Parrott M. J.; Roberts B. P. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1976, 1066–1071. [Google Scholar]; c Harris J. M.; Walton J. C.; Maillard B.; Grelier S.; Picard J.-P. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1993, 2119–2123. [Google Scholar]

- PhNMe=NO• was probably generated by H-atom abstraction from traces of the starting oxime. Iminoxyls are long-lived radicals, so they easily dominate EPR spectra out of proportion to their precursor concentration. The central sharp singlet was probably due to a trapped electron in the quartz tube.

- Walton J. C. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1998, 603–605. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; González-García N.; Truhlar D. G. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 2012–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The fact that 7g was not detected was probably due to the weakness of the spectra at higher temperatures and the larger number of lines in the spectrum of 7g compared with 6g.

- See the SI for details of the derivation of eq 1.

- Schuh H.-H.; Fischer H. Helv. Chim. Acta 1978, 61, 2130–2164. [Google Scholar]

- a Maillard B.; Walton J. C. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1985, 443–450. [Google Scholar]; b Bella A. F.; Jackson L. V.; Walton J. C. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 2002, 1839–1843. [Google Scholar]

- See:; a Beckwith A. L. J.; Brumby S. In Landolt-Börnstein: Radical Reaction Rates in Liquids; Fischer H., Ed.; Springer:Berlin, 1994; Vol. II/18a, p 171. [Google Scholar]; b Beckwith A. L. J. In Landolt-Börnstein: Radical Reaction Rates in Liquids; Fischer H.; Ed.; Springer: Berlin, 1984; Vol. II/13a, p 252. [Google Scholar]

- If it is assumed that log(Ac/s–1) = 10.5, then kc = 1 × 104 s–1 at 50 °C extrapolates to 3 × 103 s–1 at 300 K.

- Newcomb M.; Musa O. M.; Martinez F. M.; Horner J. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 4569–4577. [Google Scholar]

- a Beckwith A. L. J.; Easton C. J.; Lawrence T.; Serelis A. K. Aust. J. Chem. 1983, 36, 545–556. [Google Scholar]; b Beckwith A. L. J.; Schiesser C. H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985, 26, 373–376. [Google Scholar]

- Products from the Et2N• radical were too volatile for detection.

- Possibly 8a would undergo the same rearrangement at a higher temperature.

- Abel B.; Assmann J.; Buback M.; Grimm C.; Kling M.; Schmatz S.; Schroeder J.; Witte T. J. Phys. Chem. A 2003, 107, 9499–9510. [Google Scholar]

- Gregersen J. A.; Hao C.; Turecek F. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 5855–5864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. E.; Neville A. G.; Rayner D. M.; Ingold K. U.; Lusztyk J. Aust. J. Chem. 1996, 48, 363. [Google Scholar]

- a Beckwith A. L. J.; Hay B. P.; Williams G. M. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1989, 1202–1203. [Google Scholar]; b Hartung J.; Gallou F. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 6706–6716. [Google Scholar]

- a Pawlas J.; Begtrup M. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 2687–2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lysén M.; Madden M.; Kristensen J. L.; Vedsø P.; Zøllner C.; Begtrup M. Synthesis 2006, 3478–3484. [Google Scholar]

- a Shou W.-G.; Yang Y.-Y.; Wang Y.-G. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 9241–9243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Shabashov D.; Daugulis O. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 7720–7725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Xie C.; Zhang Y.; Huang Z.; Xu P. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 5431–5434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Bowman W. R.; Lyon J. E.; Pritchard G. J. Synlett 2008, 2169–2171. [Google Scholar]; e Blanchot M.; Candito D. A.; Larnaud F.; Lautens M. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 1486–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Ramkumar N.; Nagarajan R. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 2802–2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Katritzky A. R.; Yang B. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1996, 33, 607–610. [Google Scholar]; b Rosa A. M.; Lobo A. M.; Branco P. S.; Prabhakar S.; Pereira A. M. D. L. Tetrahedron 1997, 53, 269–284. [Google Scholar]; c Nakanishi T.; Suzuki M.; Mashiba A.; Ishikawa K.; Yokotsuka T. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 4235–4239. [Google Scholar]; d Ellis M. J.; Stevens M. F. G. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 2001, 3180–3185. [Google Scholar]; e Portela-Cubillo F.; Scott J. S.; Walton J. C. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 5558–5565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman W. R.; Lyon J. E.; Pritchard G. J. ARKIVOC 2012, vii210–227. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.