Abstract

The cardioprotective properties of erythropoietin (EPO) in preclinical studies are well documented, but erythropoietic and prothrombotic properties of EPO preclude its use in chronic heart failure (CHF). We tested the effect of long-term treatment with a small peptide sequence within the EPO molecule, helix B surface peptide (HBSP), that possesses tissue-protective, but not erythropoietic properties of EPO, on mortality and cardiac remodeling in postmyocardial infarction–dilated cardiomyopathy in rats. Starting 2 weeks after permanent left coronary artery ligation, rats received i.p. injections of HBSP (60 µg/kg) or saline two times per week for 10 months. Treatment did not elicit an immune response, and did not affect the hematocrit. Compared with untreated rats, HBSP treatment reduced mortality by 50% (P < 0.05). Repeated echocardiography demonstrated remarkable attenuation of left ventricular dilatation (end-diastolic volume: 41 versus 86%; end-systolic volume: 44 versus 135%; P < 0.05), left ventricle functional deterioration (ejection fraction: −4 versus −63%; P < 0.05), and myocardial infarction (MI) expansion (3 versus 38%; P < 0.05). A hemodynamic assessment at study termination demonstrated normal preload independent stroke work (63 ± 5 versus 40 ± 4; P < 0.05) and arterioventricular coupling (1.2 ± 0.2 versus 2.7 ± 0.7; P < 0.05). Histologic analysis revealed reduced apoptosis (P < 0.05) and fibrosis (P < 0.05), increased cardiomyocyte density (P < 0.05), and increased number of cardiomyocytes in myocardium among HBSP-treated rats. The results indicate that HBSP effectively reduces mortality, ameliorates the MI expansion and CHF progression, and preserves systolic reserve in the rat post-MI model. There is also a possibility that HBSP promoted the increase of the myocytes number in the myocardial wall remote from the infarct. Thus, HBSP peptide merits consideration for clinical testing.

Introduction

Remarkable progress in pharmacological treatment and management of chronic heart failure (CHF) has resulted in reduced or even reverse cardiac remodeling and improved survival. Nevertheless, CHF mortality remains high, the quality of a patient’s life low, and the economic burden on our health system is enormous (Morrissey et al., 2011; Nair et al., 2012). During the last decade, numerous reports have delineated cardioprotective properties of erythropoietin (EPO) in experimental animal models of acute myocardial infarction (MI) (Bogoyevitch, 2004; Lipsic et al., 2006; Koul et al., 2007; Latini et al., 2008; Riksen et al., 2008; Vogiatzi et al., 2010). It had been proposed that tissue protection and repair associated with EPO depends upon a heteromeric receptor composed of EPO receptor subunits complexed with the beta common receptor (CD131) also used by other type I cytokines, resulting in activation of a whole array of antiapoptotic and anti-inflammatory pathways (Brines et al., 2004). However, due to its erythropoietic potency, which has made EPO so useful for treatment of anemia, and due to increased risk of thrombosis (Wolf et al., 1997a,b; Stohlawetz et al., 2000; Haiden et al., 2005; Stasko et al., 2007; Kirkeby et al., 2008; Kato et al., 2010) and hypertension (Nonnast-Daniel et al., 1988; Schaefer et al., 1988; Vaziri, 1999), continuous EPO administration is unacceptable for treatment of CHF. Even a single dose of recombinant human EPO (rhEPO), in fact, can be associated with undesirable increases in platelet activation and number (Lippi et al., 2010).

Recently, based on EPO structure, different molecules have been engineered to selectively signal only through the heteromeric receptor, thereby avoiding the adverse hematopoietic side effects of EPO (Leist et al., 2004). Repeated, long-term administration of such nonerythropoietic derivatives of EPO has been proposed for treatment of CHF resulting from MI (Latini et al., 2008). One promising molecule is a small peptide [helix B surface peptide (HBSP), also called ARA290] derived from the three-dimensional structure of helix B of EPO (Brines et al., 2008), the portion of the molecule thought to interact with the heteromeric receptor. When injected intravenously twice a day for 28 days in a dose as high as 300 µg/kg, HBSP did not change the hematocrit in rabbits or the hemoglobin and platelet count in rats (Brines et al., 2008). We have recently demonstrated that HBSP is as potent as rhEPO in protecting cardiac myocytes from ischemic stress by increasing the reactive oxygen species threshold by 40% for induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition (Ahmet et al., 2011). We have also demonstrated an equal acute cardioprotective potency of a single administration of rhEPO and HBSP in a rat model of MI induced by permanent coronary artery ligation. Both agents reduced the resulting MI size by 50% at 24 hours following coronary ligation, and both agents demonstrated similar antiapoptotic and anti-inflammatory effects (Ahmet et al., 2011). Currently, the HBSP (ARA290) is in clinical development for the treatment of peripheral neuropathy (Neisters et al., 2013).

Thus, the small nonerythropoietic EPO-derived peptide, HBSP, is suitable for repeated applications, and, since it also possesses strong antiapoptotic and anti-inflammatory properties (Ahmet et al., 2011), we hypothesized that continuous administration of HBSP may be effective in the treatment of CHF. Specifically, we hypothesized that long-term treatment with HBSP will attenuate cardiac remodeling and reduce mortality in the rat model of post-MI–dilated cardiomyopathy.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Design.

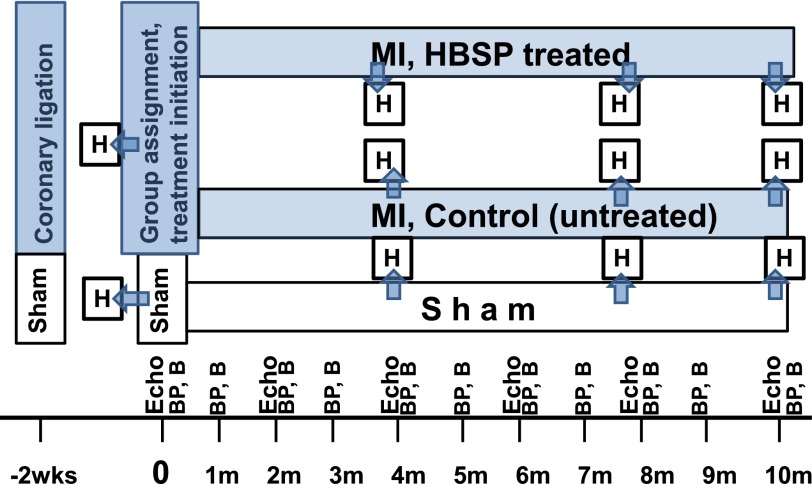

Male Wistar rats (Charles River Laboratories Inc., Wilmington, MA), weighing 225–280 g, were housed and studied in conformance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Manual 3040-2, 1999) and with approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The general experimental design and timeline of experiment is presented in Fig. 1. The left descending coronary artery was ligated in 150 rats. An additional 20 rats were sham operated without actual coronary ligation. Two weeks after surgery, left ventricular dimensions, ejection fraction (EF), and MI size were assessed by echocardiography (echo). Animals with a transmural MI greater than 20%, but less than 50% of left ventricle (LV), were divided into two groups of similar MI size (both average size and variance): the HBSP group (n = 33) received helix B surface peptide (ARA290; Araim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Ossining, NY), 60 μg/kg in 1 ml/kg volume of physiologic saline i.p., twice per week for the next 10 months; a control group (n = 33), as well as sham-operated rats (n = 20), received 1 ml/kg saline at the same time as HBSP. Animals were inspected daily for signs of moribundity by a person blinded to treatment assignments. Moribund animals were euthanized, and their hearts were harvested for histologic measurements. Daily records of dead or euthanized animals were used to calculate continuous mortality curves. Echo was repeated bimonthly, tail blood pressure measurement was repeated monthly, and tail vein blood sampling was repeated monthly following the initiation of treatment. Five animals from the MI and sham groups were removed following echo at baseline, and five animals from each group (sham, control, and HBSP) were removed following 4 and 8 months of treatment for invasive hemodynamic measurements, after which their hearts were harvested for histologic evaluation. Selection of these animals from each group was based on the results of echo, to ensure that their MI size was closest to the average for the entire group. After 10 months of treatment, following the final echo, all surviving rats were subjected to an invasive hemodynamic measurement and were euthanized. Hearts were harvested for histologic evaluation.

Fig. 1.

The diagram and timeline of experimental design. Time 0: 2 weeks following coronary ligation. At that time, all animals are subjected to echocardiography and divided into treated (HBSP) and untreated (control) groups, ensuring similar MI size in both groups. B, blood samples taken from the tail vein of subgroups of rats drafted from sham and two experimental groups; BP, noninvasive (tail cuff) measurement of arterial blood pressure in subgroups of rats drafted from sham and two experimental groups; H, cross-sectional study: subgroups of rats drafted from sham and two experimental groups for invasive hemodynamic measurements (pressure-volume loops analyses) and tissue harvesting for histologic assessment.

Coronary Artery Ligation.

Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (2% in oxygen). The surgical procedure was performed as previously described (Ahmet et al., 2005).

Echocardiography.

Following the baseline echo and initiation of treatment, echo was repeated every 2 months on all rats. Rats underwent echo (Sonos 5500, a 12-MHz transducer; Hewlett Packard, Andover, MA) under anesthesia with isoflurane (2% in oxygen) via face mask, as described previously (Ahmet et al., 2005). Rats were placed in the supine position; skin at the chest area was shaved; electrocardiogram (ECG) leads were placed at two front legs and 1 rear leg. A standard II ECG was recorded simultaneously with echo images. Parasternal long-axis views of the LV were obtained and recorded to ensure that the mitral and aortic valves and the apex were visualized. From the parasternal long-axis view of the LV, the M-mode tracings of the LV were obtained. Short-axis views of the LV were recorded at the midpapillary muscle level. Endocardial area tracings, using the leading edge method, were performed in the two-dimensional mode (short-axis, long-axis, and 4-chamber views) from digital images captured on cine loop to calculate end-diastolic and end-systolic LV areas. End-diastolic volume (EDV) and end-systolic volume (ESV) were calculated by a modified Simpson’s method. EF was derived as EF = 100*(EDV − ESV)/EDV⋅LV mass was calculated from a two-dimensional mode image. The MI size was estimated from two-dimensional short-axis LV images at the midpapillary muscle level, measured at the end diastole as a percentage of infarct length from the total LV endocardial circumference. The transmural MI was identified as a sharply demarcated section of the LV-free wall that failed to thicken during systole. Each cardiac cycle was examined in a slow-motion movie; the MI area was identified at end systole, and MI length was measured at the end diastole from freeze-frame images. Posterior wall thickness was measured from M-mode tracing. All measurements were made by a single observer who was blinded to the identity of the tracings. All measurements were offline averaged over three to five consecutive cardiac cycles. Since breathing rate was averaging 60 times/min during echo examination, the effect of respiratory movement was distributed over the averaging sample. The reproducibility of measurements was assessed in two sets of baseline measurements in 10 randomly selected rats, and the repeated-measure variability did not exceed ± 5%.

Noninvasive Blood Pressure Monitoring.

Blood pressure was repeatedly measured on the same 10 rats from each group every month following the initiation of treatment. Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (2% in oxygen) and arterial blood pressure was measured (Coda-6; Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT) using a noninvasive tail-cuff technique according to the manufacturer’s specification.

Tail Vein Blood Sampling for Hematocrit Measurements.

Blood samples were collected from the tail vein using a rat restrain. The blood hematocrit level was measured on the same 10 rats from each group every month following the initiation of treatment.

Hemodynamic Measurements.

Invasive hemodynamic measurements were conducted in subgroups of animals at baseline, at 4 and 8 months of treatment, and on all surviving rats at the end of the 10-month treatment protocol. LV pressure-volume loop analyses were conducted as described previously (Ahmet et al., 2005). Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (2% in oxygen), intubated, and ventilated. Breathing rate was 60 times/min with a tidal volume of 100 ml/100 g of body weight. Rats were kept in the supine position on a heating pad. ECG leads were placed at limbs, and a standard II ECG was recorded continuously. After chest skin was shaved, a bilateral thoracotomy was performed in the sixth intercostal space, and the pericardium was exposed. A 1.4F-combined pressure-conductance catheter (Millar Instruments Inc., Houston, TX) was inserted into the LV through the apex. Catheters were calibrated before each use according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. A 2-0 ligature was placed on the inferior vena cava above the diaphragm for load manipulations. Traditional load-dependent hemodynamic indices—EF, the rate of rise (+dP/dt) and fall (−dP/dt), end-diastolic pressure, and isovolumic relaxation time constant (τ)—were measured from 10∼15 steady loops, and load-independent indices, i.e., end-systolic elastance (Ees), preload recruitable stroke work (PRSW), and end-diastolic stiffness (Eed), were determined or calculated from 10∼15 loops during a brief occlusion of inferior vena cava. Loops were recorded continuously throughout the examination. For steady-state and occlusion loop recordings, the respirator was stopped briefly for about 5 seconds each time. A parallel conductance (Vp) was determined by rapidly injecting 30 μl of 10% NaCl solution from the left femoral vein. A volume unit conversion from voltage to microliter was conducted before the experiment using a series of fresh-blood-filled cuvettes as recommended by the manufacturer. Effective arterial elastance (Ea) was calculated as the index of vascular tension. Arterioventricular coupling, an index of cardiac work efficiency, was calculated as arterioventricular coupling (Ea/Ees). All analysis was performed offline using PVAN software (version 3.6; Millar Instruments Inc.).

Histologic Measurements.

Histologic staining and analyses were performed as described previously (Ahmet et al., 2005). Briefly, the hearts were isolated, weighed, and cut into two pieces through the short axis. The basal half was snap frozen and stored at −80°C, and the apical half was used for histologic analysis. Myocardial tissue segments were imbedded in paraffin, sectioned (5 µm), and stained with Masson’s trichrome, hematoxylin and eosin, or terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated digoxigenin-deoxyuridine nick-end labeling (TUNEL). MI size was expressed as an average percentage of the LV endocardial and epicardial circumferences that were identified as infarcted area in the Masson’s trichrome–stained sections. Myocyte cell size and density were measured in H&E-stained sections of the LV posterior wall. Only myocytes in which nuclei were clearly identified were counted. Myocyte diameter was measured as the shortest distance across the nucleus in transverse cell sections. Diameters of 100 myocytes from five randomly selected microscope fields (200× magnification) from the LV posterior wall were averaged to represent the myocyte diameter of a given specimen. Myocyte density was calculated from the same areas in the same fashion. The average number of transmural cardiomyocytes in the posterior wall was calculated as Nmtm = 1.0243 PWth × √Nma, where Nmtm is the number of transmural myocytes, Nma is the cardiomyocyte density, and PWth is the thickness of LV posterior wall (Olivetti et al., 1992). Myocardial tissue fibrosis was measured in Masson's trichrome–stained sections and was expressed as a fraction of a microscopic field (100× magnification) of the LV posterior wall. Five randomly selected fields were averaged to represent a given specimen. The number of TUNEL-positive cardiomyocyte nuclei was counted manually in whole, noninfarcted myocardium, including the LV posterior wall and septum, under light microscopy from each LV short-axis section. Only nuclei clearly located within cardiomyocytes were counted and expressed as a percentage of total myocytes in a given LV section.

Detection of Anti-ARA290 Antibodies in Rat Serum.

Samples of blood plasma were analyzed for the presence of anti-ARA290 IgG and IgM antibodies at Charles River Laboratories (Montreal, QC, Canada) using qualitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Statistical Analyses.

All data are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. Mortality is reported via Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Differences among survival curves were assessed using log rank statistical analyses (GraphPad Prism 4.02; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Repeated echo and hemodynamic measurements were analyzed using repeated-measures linear mixed-effects models. Each response variable was analyzed for main effects of group and time, as well as group and time interactions. If group-time interactions were statistically different among groups, data at different time points were compared using the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Group differences in histologic data among groups were assessed by one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-hoc corrections as appropriate. Statistical significance was assumed at P < 0.05.

Results

Early Mortality, Cardiac Remodeling, and Baseline MI Size.

Perioperative mortality among coronary ligated animals was 30.6% (46 rats). Two additional rats died within 2 weeks after surgery. There was zero mortality in sham-operated rats. The 95 rats that survived 2 weeks after surgery were subjected to a baseline echo. Twenty-nine rats with nontransmural MIs, or with transmural MIs that were less than 20% or more than 50% of LV, were excluded from further study. Following echo measurements at 2 weeks post-MI, 66 coronary ligated rats were divided into untreated (control, n = 33) and treated (HBSP, n = 33) groups with equal MI average size and variance. Pretreatment baseline data, i.e., 2 weeks post-MI echo, for control, HBSP, and sham-operated rats are presented in Table 1. The MI size among coronary ligated rats was similar in both groups: 27.6 and 30.3% of LV for animals assigned to the control and HBSP groups, respectively. At the time of echo measurements, body weights and heart rate were similar between experimental groups and did not differ from sham. Compared with sham, the EDV among coronary ligated rats was increased by 56% and the ESV by 175–200%, whereas the EF was reduced by 40–50%. The posterior wall thickness in coronary ligated rats was 9% less than in sham, but the difference was not statistically significant. Thus, echo parameters among coronary ligated rats indicated a significant early cardiac remodeling, but, as intended by design, there were no differences in the extent of remodeling between designated control and HBSP groups during the first two weeks post-MI.

TABLE 1.

Pretreatment baseline values of LV remodeling and MI size in sham-operated rats and MI rats assigned to experimental groups at 2 weeks following coronary ligation

| Groups | N | BW | HR | EDV | ESV | EF | PWth | MI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g | beats/min | µl | µl | % | mm | % | ||

| Sham | 10 | 330 ± 7 | 403 ± 9 | 414 ± 17 | 165 ± 9 | 60 ± 1.5 | 1.52 ± 0.06 | NA |

| Control | 33 | 326 ± 4 | 402 ± 7 | 646 ± 17* | 455 ± 17* | 30 ± 1.2* | 1.39 ± 0.04 | 27.6 ± 1 |

| HBSP | 33 | 328 ± 4 | 410 ± 5 | 646 ± 21* | 493 ± 19* | 24 ± 1.4* | 1.39 ± 0.04 | 30.3 ± 1 |

BW, body weight; HR, heart rate; NA, not applicable.

P < 0.05 versus sham (one-way analysis of variance and post-hoc Bonferroni comparison).

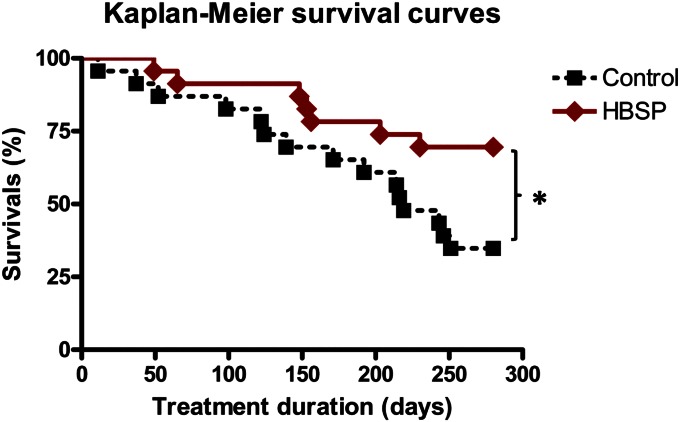

Mortality

At the end of the study, the mortality in HBSP-treated group was half of that in the untreated group. Figure 2 illustrates Kaplan-Meier survival curves for control (untreated) and HBSP (treated) groups, each consisting of 23 animals at baseline. After 10 months of treatment, the experiment was terminated because only 8 animals remained alive in the untreated group—a minimal number necessary to conduct statistically meaningful terminal hemodynamic measurements (Table 2). Mortality among the HBSP group at this time, however, was only half as much compared with the control group, translating into 2-fold improvement in 10-month survival (P < 0.001). The median survival time for the control group was 219 days, whereas the HBSP group had only 30% mortality at 280 days.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves after induction of MI in control (untreated, n = 23) and HBSP (treated, n = 23) groups. There was no mortality among sham-operated rats. Statistical differences between groups were determined using a log-rank test.

TABLE 2.

Hemodynamic and histologic measurements in rats that survived 10 months post initiation of treatment with HBSP or were untreated

Values are the mean ± S.E.M.

| Sham (n = 10) | Untreated (Control, n = 8) | Treated (HBSP, n = 15) | ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BW (g) | 672 ± 22 | 676 ± 13 | 655 ± 12 | |

| Hemodynamics | ||||

| HR (beats/min) | 282 ± 8 | 317 ± 28 | 308 ± 19 | |

| ESV (µl) | 270 ± 20 | 1121 ± 143* | 739 ± 60*# | $ |

| EDV(µl) | 556 ± 20 | 1184 ± 137* | 911 ± 63* | $ |

| ESP (mm Hg) | 93 ± 4 | 86 ± 5 | 87 ± 5 | |

| EDP (mm Hg) | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 6.4 ± 1.7 | 5.0 ± 0.5 | |

| SV (µl) | 329 ± 19 | 120 ± 22* | 201 ± 21*# | $ |

| EF (%) | 59 ± 2 | 10 ± 1* | 23 ± 3*# | $ |

| CO (ml/min) | 94 ± 7 | 39 ± 8* | 62 ± 7* | $ |

| Ea (mm Hg/µl) | 0.29 ± 0.03 | 0.77 ± 0.09* | 0.43 ± 0.05# | $ |

| dP/dt+ (mm Hg/sec) | 6809 ± 283 | 4369 ± 332* | 5440 ± 319* | $ |

| dP/dt- (mm Hg/sec) | 7354 ± 645 | 4265 ± 427* | 5011 ± 385* | $ |

| Tau (ms) | 9.1 ± 0.5 | 11.7 ± 1.1 | 10.9 ± 0.6 | |

| PRSW (mm Hg*µl/µl) | 69 ± 4 | 40 ± 5* | 63 ± 4# | $ |

| Ees (mm Hg/µl) | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 0.40 ± 0.07 | 0.46 ± 0.07 | |

| Eed (10-3*mm Hg/µl) | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.5* | 1.9 ± 0.3*# | $ |

| Ea/Ees | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.7* | 1.2 ± 0.2# | $ |

| Histology | ||||

| MI (% of LV) | NA | 45 ± 3 | 35 ± 2# | NA |

| HW/BW (g/kg) | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.2* | 3.9 ± 1.9* | $ |

| PW thickness (mm) | 2.5 ± 0.07 | 2.33 ± 0.05 | 2.85 ± 0.09# | $ |

| Myocyte density (#/mm2) | 1278 ± 55 | 730 ± 28* | 873 ± 31*# | $ |

| Myocyte diameter (µm) | 24 ± 0.1 | 34 ± 1.7* | 33 ± 0.8* | $ |

| TUNEL(+) in myocytes (%) | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.4 ± 0.07* | 0.3 ± 0.03*# | $ |

| Collagen in PW (%) | 1.0 ± 0.07 | 2.6 ± 0.3* | 1.7 ± 0.2# | $ |

ANOVA, analysis of variance; BW, body weight; CO, cardiac output; EDP, end-diastolic pressure; ESP, end-systolic pressure; HR, heart rate; HW, heart weight; NA, not applicable; SV, stroke volume.

$P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA for three groups); *P < 0.05 (post-hoc Bonferroni comparison versus sham); #P < 0.05 (post-hoc comparison versus untreated group).

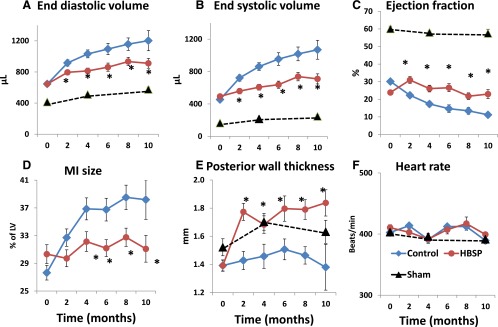

Serial Echo Measurements of LV Remodeling and MI Expansion

LV remodeling, progressive functional decline, and MI expansion observed in untreated the group were significantly attenuated in the HBSP group. Reduced thickness of the posterior wall observed 2 weeks after coronary ligation and maintained among untreated animals through the study was restored in HBSP rats to the level of sham animals.

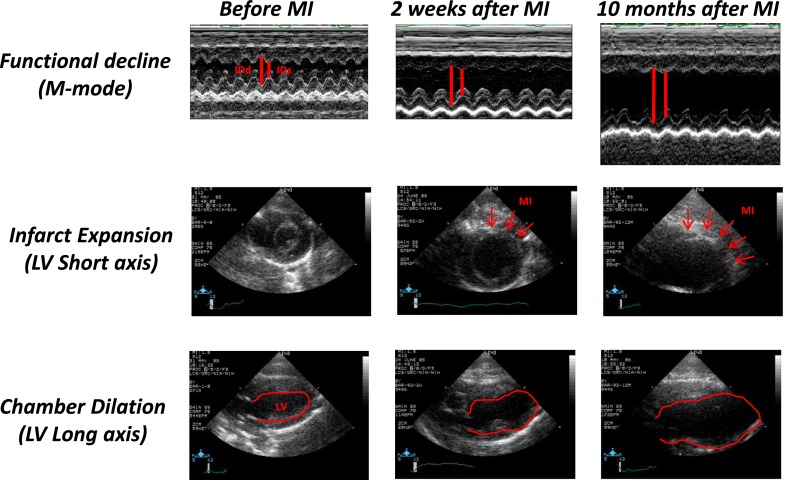

Representative sonograms of untreated hearts (control group) before coronary ligation, 2 weeks after ligation (baseline for treatment), and 10 months after initiation of treatment/observation are shown in Fig. 3 in M-mode (upper row), transverse view in B-mode (middle row, MI measurement), and long-axis view (bottom row, LV measurement). Results of serial measurements of LV remodeling and MI expansion are presented in Fig. 4. During 10 months of observation, the MI size in control (untreated) rats increased from 27% of LV to 38% of LV, whereas in the HBSP group, the MI size remained unchanged. Beginning in the fourth month and continuing to the end of observation, the MI size was significantly (P < 0.01) smaller in the HBSP versus control group (Fig. 4D). During that time, EDV doubled in control rats (Fig. 4A) and ESV (Fig. 4B) increased by 135%, resulting in a decline of EF (Fig. 4C) from 30% 2 weeks after coronary ligation to 11% at 10 months. Expansion of LV volumes in HBSP rats was markedly attenuated and, although remaining above that of sham-operated animals, was significantly lower than that in control animals at all time points (P < 0.01). Attenuation of LV remodeling in the HBSP group was associated with a preservation of EF at the baseline pretreatment level (2 weeks post-MI), and EF remained above that of the control group at all time points (P < 0.01). The echo-derived thickness of the posterior wall in the HBSP group (Fig. 4E) increased to the level of sham-operated rats after initiation of treatment, and was thicker than in the control group at all time points (P < 0.01). Heart rate during echo measurements was similar among all groups (Fig. 4F). Serial echo data for animals who survived to the end of experimental protocol (in comparison with data from all animals) are presented in Supplemental Fig. 1. The general pattern of LV remodeling, functional decline, and MI expansion among only animals surviving to the end of experimental protocol remained similar to that for all rats presented in Fig. 2; however, LV volumes and MI size were slightly and statistically not significantly smaller in the surviving rats than in the entire group, reflecting a trend toward higher mortality among animals with larger MI and more extensive LV remodeling.

Fig. 3.

Representative sonograms of untreated hearts before MI induction (left column), 2 weeks after MI induction (middle column), and 10 months after MI induction (right column) in M-mode (upper row) and B-mode at the short (middle row) and long (bottom row) axes. MI size is measured in the short axis. MI is defined as an akinetic part of myocardium in systole and measured in diastole. It is expressed as a percentage of circumference at the midpapillary level.

Fig. 4.

Repeated echocardiographic measurements in sham, control, and HBSP groups at baseline (0, 2 weeks after coronary ligation) and after initiation of treatment, every two months for 10 months. (A) LV end-diastolic volume. (B) LV end-systolic volume. (C) Ejection fraction. (D) MI size. (E) Posterior wall thickness at diastole. (F) Heart rate. *P < 0.05 versus control (analysis of variance with post-hoc Bonferroni correction).

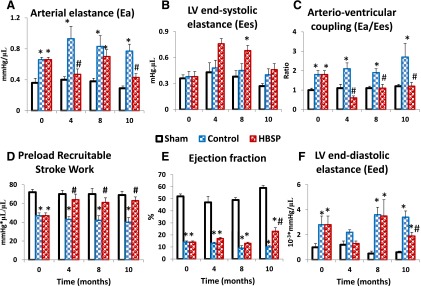

Hemodynamic Assessments in Rats Removed from the Study at Different Intervals or Study Termination

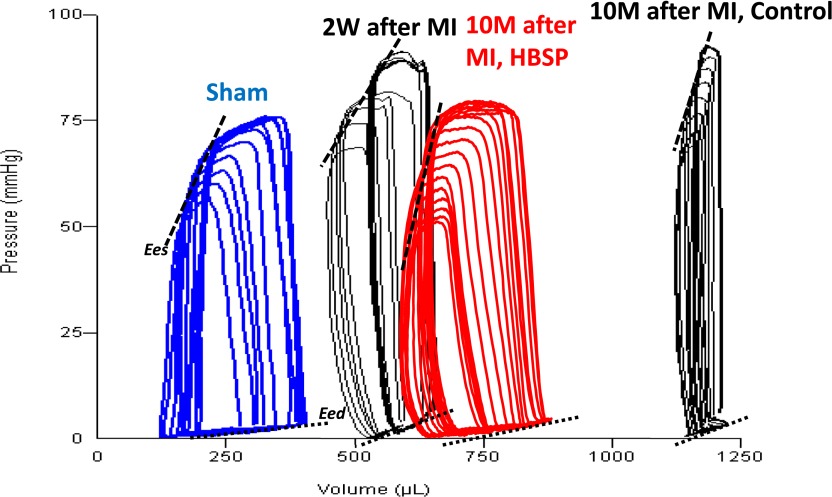

All hemodynamic parameters compromised in untreated MI animals improved in the HBSP group. Increased arterioventricular coupling and decreased PRSW observed in untreated animals was normalized in the HBSP group.

Representative series of PV loops under preload reduction from the sham-operated group, the MI group 2 weeks after surgery (baseline before treatment), and two MI groups, treated and untreated after 10 months of observation are presented in Fig. 5. Cardiac function assessed at the end of 10 months of observation in all surviving rats via invasive pressure-volume analyses is presented in Table 2. Steady-state measurements at 10 months confirmed the progression of LV remodeling captured by serial echo measurements, i.e., marked expansion of LV volumes and reduction of EF, stroke volume and cardiac output in untreated post-MI rats, with significant improvement of most of these parameters in HBSP-treated post-MI rats. A marked increase in Eed occurred in untreated rats (P < 0.001) but to a lesser extent in HBSP-treated rats (P < 0.05). Load-independent systolic function, assessed by PRSW, also declined significantly in untreated animals (P < 0.001), but was fully preserved in the HBSP group. Compared with sham, Ea/Ees doubled in control rats (P < 0.001), but was completely normal in the HBSP group, mainly due to normalization (to the level of sham) of Ea, because Ees was not different from the control group. Figure 6 illustrates the progression of selected hemodynamic indices based on cross-sectional data from subgroups of animals removed from the study at baseline, 4, 8, and 10 months. Complete invasive hemodynamic data at baseline, 4, and 8 months are presented in Supplemental Tables 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Significant improvement in cardiac function in the HBSP group, including normalization of PRSW and Ea/Es, occurred early, at the fourth month measurement (Fig. 6, C and D). Improvements in EF and Eed in the HBSP group were observed only in the rats surviving until the end of the study (Fig. 6, E and F).

Fig. 5.

Representative pressure-volume loops during preload reduction in sham and MI animals 2 weeks after MI induction, 10 months after MI induction, and 10 months after MI induction and treatment with HBSP.

Fig. 6.

Selective hemodynamic cross-sectional measurements in subgroups of rats removed from the study at baseline and 4, 8, and 10 months after initiation of treatment. (A) Ea. (B) LV Ees. (C) Ea/Ees. (D) PRSW. (E) EF. (F) LV Eed (stiffness). *P < 0.05 versus sham; #P < 0.05 versus control (analysis of variance with post-hoc Bonferroni correction).

Morphologic Measurements

HBSP treatment attenuated the apoptosis and fibrosis in myocardium and reduction of cardiomyocyte density observed in untreated MI animals.

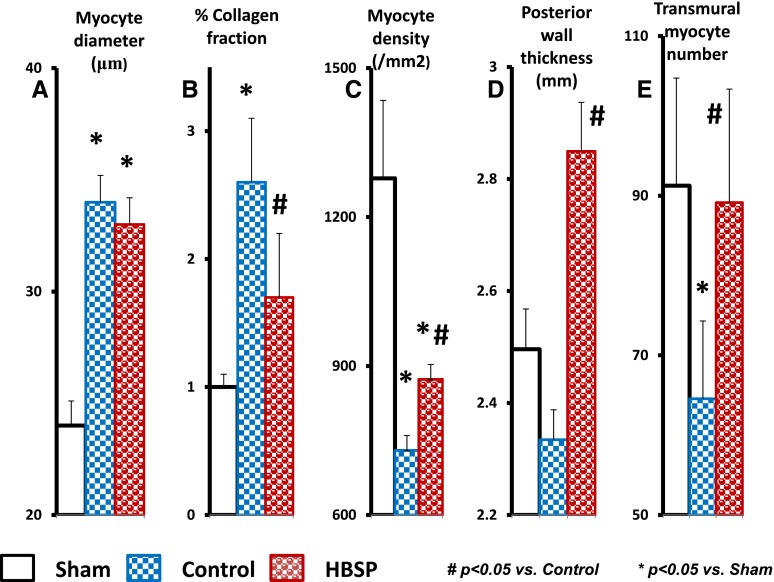

Histologic assessment of myocardium of the rats surviving to the end of the 10-month experiment is presented in Table 2 and Fig. 7, and measurements in subgroups at baseline, month 4, and month 8 are presented in Supplemental Tables 1, 2, and 3, respectively. As defined by echo, the average MI size was significantly smaller in the HBSP group at all time points (P < 0.001). The number of TUNEL-positive cardiomyocytes in the posterior wall of MI rats was significantly higher compared with sham, but this number was significantly reduced in the HBSP group versus control group (P < 0.05). The extent of fibrosis in the posterior myocardial wall following MI was more than 2-fold higher in control group rats than in sham, but it was significantly less in the HBSP group, in which it was similar to sham. The diameter of cardiomyocytes did not differ between the control and HBSP groups, and was significantly larger than in the sham group at all time points (P < 0.05), reflecting the extent of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Cardiomyocyte density was markedly lower in the control and HBSP groups than in the sham group (P < 0.01) at all time points, but was significantly higher, however, in the HBSP group than in the control group (P < 0.05) at the end of the experiment. The posterior wall thickness measured histologically (Table 2) as well as derived by echo (Fig. 4) was increased in the HBSP group, exceeding that in the control group by 22% (P < 0.001). As a combined result of changes in cardiomyocyte density and LV posterior wall thickness, the calculated average number of transmural cardiomyocytes was significantly reduced in the control MI group, but was increased to the level of sham in the HBSP group (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Selected morphologic characteristics of the myocardium in rats from sham, control, and HBSP groups survived to the end of 10 months of observation and treatment. (A) Cardiomyocyte diameter. (B) Collagen fraction. (C) Cardiomyocyte density in LV posterior wall. (D) Posterior wall thickness. (E) Average transmural cardiomyocyte number. *P < 0.05 versus sham; #P < 0.05 versus control (analysis of variance with post-hoc Bonferroni correction).

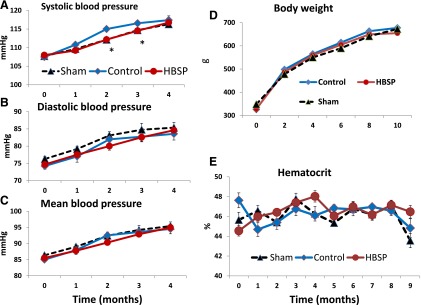

Other Measurements

HBSP treatment did not affect the hematocrit and arterial blood pressure, and did not evoke any immune response. Figure 8 illustrates some general indices that might constitute side effects of treatment. Body weight (Fig. 8D) progressively increased during the course of the 10-month experiment, reflecting normal growth of animals at the age they were recruited for the study; however, there were no differences among sham and the two experimental MI groups. Arterial blood pressure (Fig. 8, A–C), measured during the first four months of observation, gradually increased in parallel with increase in body weight. At no time was blood pressure in the HBSP group different from sham, but at the second- and third-month measurements, the systolic blood pressure in control animals was slightly, but statistically, significantly higher than in the sham group. Measurement of blood pressure was terminated after the fourth month, because the number of animals in the subgroup of untreated animals randomly selected for blood pressure measurement fell below that required for statistical comparison. The hematocrit, measured monthly (Fig. 8E), did not change significantly during the 10-month experiment, and there were no differences among groups. Serum assays did not detect any antibodies to ARA290 (HBSP) or to IgM in the plasma of HBSP-treated rats (unpublished data).

Fig. 8.

Arterial blood pressure [systolic (A), diastolic (B), and mean (C)], body weight (D), and hematocrit (E) in sham, control, and HBSP groups. Arterial blood pressure measurements were terminated after 4 months because excessive mortality in untreated MI rats (control group) precluded statistically meaningful future measurements. *P < 0.05 (analysis of variance with post-hoc Bonferroni correction).

Discussion

In the rat model of postmyocardial infarction–dilated cardiomyopathy 10-month treatment with helix B surface peptide, a small peptide synthesized to mimic a nonerythropoietic part of EPO molecule binding to the beta common receptor reduced mortality, ameliorated maladaptive cardiac remodeling, arrested the MI expansion, and restored systolic reserve. Increased cardiomyocyte density in the posterior wall of the left ventricle, in combination with restored thickness of the posterior wall, suggested an increase in cardiomyocyte numbers in noninfarcted myocardium.

Primum Non Nocere.

Erythropoietin, an experimentally proven strong tissue- and cardio-protective agent (Bogoyevitch, 2004; Brines and Cerami, 2006, 2008; Lipsic et al., 2006; Koul et al., 2007; Arcasoy, 2008; Latini et al., 2008; Riksen et al., 2008; Vogiatzi et al., 2010), cannot routinely be used in chronic heart failure because repeated EPO injections increase the hematocrit, blood viscosity, and blood pressure (Nonnast-Daniel et al., 1988; Schaefer et al., 1988; Wolf et al., 1997a,b; Vaziri, 1999; Stohlawetz et al., 2000; Haiden et al., 2005; Stasko et al., 2007; Kirkeby et al., 2008; Kato et al., 2010). The present study used a small peptide (HBSP) constructed to mimic helix B, a tissue-protective sequence of the tertiary structure of EPO, that presumably does not bind to the classic EPO receptor complex and therefore is not erythropoietic or prothrombotic (Brines et al., 2008). Indeed, we demonstrated that 10 months of 60 µg/kg i.p. administration of HBSP twice per week did not affect the hematocrit. Moreover, continuous HBSP administration did not produce any signs of an immune reaction or arterial blood pressure elevation. Therefore, results of our experiment confirmed a previous assertion that continuous administration of HBSP does not trigger undesirable erythropoietic or hemodynamic effects of EPO, which have clearly been documented to occur during its continuous administration. The absence of differences in body weight gain among experimental groups during 10 months of observation also supports the notion of safety of continuous administration of HBSP, at least in animal models. This conclusion is supported by a recently completed randomized, double-blind, pilot study, in which ARA290 (HBSP) was used in a patient with sarcoidosis: after 4 weeks of intravenous injection of 2 mg of ARA290 three times per week, clinical and laboratory evaluation did not raise any safety concerns (Heij et al., 2013).

Reduced Mortality.

Mortality in rats treated with HBSP was only half of that in untreated animals; the actual number of rats in the HBSP group surviving for 10 months after MI induction was double that in the untreated group. This formidable mortality outcome matches outcomes in similar experimental models investigating single drugs, or a combination of drugs, that constitute the present standard of care for chronic heart failure patients (Morrissey et al., 2011). The magnitude of survival benefit of these treatments in the rat model of post-MI–dilated cardiomyopathy has varied among different studies, likely due to differences in duration of therapy, dosage, time of treatment initiation, and original size of induced MI. In one of the first, and now a classic study (Pfeffer et al., 1985, 1987), a one-year treatment with the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor captopril improved mortality in rats with moderate MI by 27%. In a study that featured very large (50% of LV) infarcts, nine-month mortality was reduced by 61% in rats treated with the ACE inhibitor lisinopril (Mulder et al., 1997). In another study (Richer et al., 1999), 7.5 months of treatment with the angiotensin II receptor blocker irbesartan significantly and dose dependently improved survival in rats with an MI induced by a coronary ligation: at 50 mg/kg/day, survival improved by 65% compared with placebo. In our prior study (Ahmet et al., 2009), which used a methodology identical to the present study, the one-year survival in rats with a moderate-size MI continuously treated with a combination of ACE inhibitor and β1 adrenergic receptor (β1AR) blocker was 25% greater than in rats treated with placebo. Supplemental Figure 2 compares 10-month survival curves from the present study and from our previous study (Ahmet et al., 2009), in which 10-month survival of untreated coronary ligated rats was compared with those treated with a combination of ACE inhibitor and β1AR blocker: the survival benefit of both therapies is similar. Therefore, in the rat model of post-MI chronic heart failure, the therapy with HBSP elicits a survival benefit that is at least comparable to other existing therapeutic regimens.

Attenuated LV Remodeling.

Cardiac remodeling in the control (untreated) group was similar to that described in our prior study of the same design (Ahmet et al., 2009). Attenuation of LV volume expansion observed in the present experiment in rats treated with HBSP was also similar to the previously described effect of continuous treatment with a combination of ACE inhibitor and β1 blocker (Ahmet et al., 2009). The effect of HBSP to preserve EF and limit MI expansion, however, appears stronger than the ACE inhibitor and β1 blocker combination: EF and MI size in HBSP-treated rats remained at the baseline levels throughout the entire 10-month observation. A remarkable difference between treatment with HBSP compared with previously described therapies in the rat model of post-MI–dilated cardiomyopathy was observed with respect to the thickness of the posterior wall. Specifically, whereas treatment with an ACE inhibitor/β1 blocker combination prevented progressive thinning of the posterior wall observed in untreated rats (Ahmet et al., 2009), HBSP, soon after initiation of treatment, actually increased the posterior wall thickness to a level comparable to sham-operated animals, and this increased thickness was maintained throughout the observation period. Therefore, in some respects, the beneficial effect of HBSP treatment on cardiac remodeling appears to exceed the effect of a standard therapeutic regimen.

Cardiac Hemodynamics and Morphology.

Pressure-volume loop analyses conducted at the end of the observation confirmed the conclusions drawn from the echo evaluation: HBSP-treated rats had less LV dilatation and an attenuated reduction of EF compared with their untreated counterparts. The HBSP group also had reduced Eed and a normalized Ea/Ees, indicating optimal efficiency of blood transfer from the heart to the arterial system. The latter was achieved via a reduction of Ea rather than through an increase of LV end-systolic elastance, which was slightly elevated in both MI groups but was not affected by treatment. The reduction in Ea might result from activation of nitric oxide (NO) pathways. Association of EPO with endothelial NO had been known. Recently, Sautina et al. (2010) reported that the heterocomplex formed by the EPO receptor and common β receptor, a presumed mechanism of tissue protection (Brines et al., 2004, 2008), activates the endothelial nitric oxide and involves vascular endothelial growth factor. It is conceivable that activation of the common β receptor by HBSP has an effect similar to NO activation.

The improvements among HBSP-treated rats are similar to those described for the ACE inhibitor and β1AR blocker combination in our previous experiments (Ahmet et al., 2009). What distinguishes the hemodynamic outcome of HBSP therapeutic intervention from prior CHF intervention studies is full normalization of systolic reserve function as measured by PRSW, which remained at the level of sham-operated rats. This normalization of PRSW, which began early after initiation of treatment (Fig. 3D), indicates the ability of the heart to maintain its work at different levels of preload, suggesting a preservation of systolic reserve. Improvement of PRSW in the HBSP group was probably associated with a reduction of end-diastolic stiffness (observed in the control, untreated group) that allowed for better LV filling, and thus myocardial stretching at the same level of preload. The reduction of Eed in the HBSP group was achieved through a reduction of myocardial fibrosis and, likely, through activation of NO pathways. However, improvement of PRSW in HBSP rats, which occurred within the same time course as the recovery of LV posterior wall thickness, to the level of sham-operated animals exceeded the effect observed in previously described therapeutic regimens (Ahmet et al., 2009) achieving full recovery to the level of sham, suggesting that HBSP might be superior to the standard therapy (ACE inhibitor and β1AR blocker combination) for chronic heart failure.

There is a noticeable discrepancy between PRSW, which increased to a near normal level in HBSP-treated rats, and Ees that remained at the level of untreated animals. This apparent discrepancy stems from the fact that Ees is the most appropriate index to characterize the acute effects on contractility, because in chronic conditions, structural changes in myocardium result in additional factors affecting measurement. Fibrosis developing in myocardium over time following MI limits the full stretching of cardiomyocytes necessary to enable their full contractile response; at the same time, fibrosis amplifies the contractile response by increasing the passive elastance of myocardium. Reduced myocardial fibrosis in the HBSP-treated group results in the reverse effect—better LV filling/myocyte stretching, but reduced contribution of passive elastance to contractility. The net result of this opposite dynamic is a similar Ees in treated and untreated groups. Therefore, although reduction of Ea is an unquestionable contributor to a reduction of Ea/Ees in the HBSP group, the Ees contribution is not as clear cut, making the apparent Ea/Ees normalization less obvious, and explaining why the EF was not restored in the HBSP group to a greater degree.

Potential mechanisms involved in attenuation of LV remodeling and hemodynamic improvements, especially normalization of load-independent LV work and cardiac efficiency in HBSP-treated MI rats, are reflected in morphologic improvements in matrix and increased cardiomyocyte density associated with reduced apoptosis. As illustrated in Fig. 4, an increase in cardiomyocyte density in the myocardium of HBSP-treated rats compared with untreated MI rats was observed in the context of less myocardial fibrosis in the HBSP group, whereas the average myocyte size was similar between groups. This morphologic pattern suggests that the number of cardiomyocytes in the myocardium of HBSP rats is higher than in untreated rats. Indeed, in combination with posterior wall thickness, which was significantly thicker in the HBSP group than in the control group and similar to the sham group, higher cardiomyocyte density in HBSP strongly suggests an increased number of cardiomyocytes in the noninfarcted area of myocardium (Fig. 4E). Therefore, morphologic assessment suggests that HBSP treatment in post-MI–dilated cardiomyopathy results in both cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia in myocardium. The latter conclusion is supported by studies on the cellular level demonstrating that erythropoietin stimulates a proliferative response in murine myoblasts (Ogilvie et al., 2000) and protects cardiac myocyte progenitors against the cytotoxic effects of tumor necrosis factor α (Madonna et al., 2009).

In summary, HBSP, a small nonerythropoietic peptide designed to mimic helix B, a tissue-protective region of the tertiary structure of the EPO molecule, which does not elicit classic EPO receptor signaling, presents a novel, potent, and safe therapeutic intervention in the rat model of post-MI–dilated cardiomyopathy. With respect to survival and cardiac remodeling, the efficacy of HBSP therapy is comparable to previously used therapeutic strategies, but HBSP appears to exceed the latter with respect to preservation of numerous aspects of cardiac structure and cardiac and arterial function. Thus, HBSP merits consideration as a novel therapy in clinical intervention trials for cardiomyopathy.

Translational Potential and Study Limitations.

Given significant improvement in mortality and cardiac remodeling demonstrated in the rat model of post-MI–dilated cardiomyopathy, the helix B surface peptide, aka ARA290, is certainly suitable for further testing in patients suffering from CHF. However, some additional animal experiments are also warranted. First, although the therapeutic effect of HBSP is similar to or better than that of other current therapies for CHF tested in the same experimental model, it is unknown whether addition of HBSP to a standard therapeutic arsenal would provide any additional benefit. Second, although lower doses than used in this study were effective in acute cardioprotection (Ahmet et al., 2011), their utility in the model of dilated cardiomyopathy had not been tested. The frequency of drug administration used in this study (two times per week) was arbitrarily chosen—the effectiveness of different frequencies should be tested. Third, currently used parenteral route of drug delivery is not optimal for a clinical setting. A more appropriate drug delivery route should be explored. Finally, the most important outcome of the present study—a potential increase of the cardiomyocyte number in HBSP-treated rats—should be verified and directly demonstrated in specially designed follow-up studies, and, if confirmed, the mechanisms of this phenomenon should be explored.

The overall conclusion of the present study is well supported by data combined from different functional and morphologic measurements. Nevertheless, one should exercise a certain degree of caution in interpreting some specific echocardiographic and pressure-volume loop indices derived from isoflurane-anesthetized animals in our study. A possible effect of anesthesia on the measurements of cardiovascular functions is unavoidable in these types of experiments. There is substantial evidence that isoflurane anesthesia might affect the LV afterload through its action on aortic compliance. Moreover, this effect could be different in a normal cardiovascular system and in the heart affected by dilated cardiomyopathy (Hettrick et al., 1997). Unfortunately, other types of anesthesia have even more negative characteristics, making inhalation narcosis (isoflurane) the anesthesia of choice in experimental studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate the technical assistance of Tia Turner. HBSP was provided by Araim Pharmaceuticals.

Abbreviations

- ACE

angiotensin-converting enzyme

- β1AR

β1adrenergic receptor

- CHF

chronic heart failure

- Ea

arterial elastance

- Ea/Ees

arterioventricular coupling

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- echo

echocardiography

- EDV

end-diastolic volume

- Eed

end-diastolic stiffness

- Ees

end–systolic elastance

- EF

ejection fraction

- EPO

erythropoietin

- ESV

end-systolic volume

- HBSP

helix B surface peptide

- LV

left ventricle

- MI

myocardial infarction

- PRSW

preload recruitable stroke work

- PWth

thickness of the LV posterior wall

- NO

nitric oxide

- rhEPO

recombinant human EPO

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated digoxigenin-deoxyuridine nick-end labeling

- τ

isovolumic relaxation time constant

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Ahmet, Lakatta, Talan.

Conducted experiments: Ahmet, Tae.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Brines, Cerami.

Performed data analysis: Ahmet, Tae, Talan.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Brines, Talan, Lakatta.

Footnotes

This work was fully funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health [National Institute on Aging]. M.B. and A.C. are employees of Araim Pharmaceuticals, which owns the intellectual property of the peptide.

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Ahmet I, Lakatta EG, Talan MI. (2005) Pharmacological stimulation of beta2-adrenergic receptors (beta2AR) enhances therapeutic effectiveness of beta1AR blockade in rodent dilated ischemic cardiomyopathy. Heart Fail Rev 10:289–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmet I, Morrell C, Lakatta EG, Talan MI. (2009) Therapeutic efficacy of a combination of a beta1-adrenoreceptor (AR) blocker and beta2-AR agonist in a rat model of postmyocardial infarction dilated heart failure exceeds that of a beta1-AR blocker plus angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 331:178–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmet I, Tae HJ, Juhaszova M, Riordon DR, Boheler KR, Sollott SJ, Brines M, Cerami A, Lakatta EG, Talan MI. (2011) A small nonerythropoietic helix B surface peptide based upon erythropoietin structure is cardioprotective against ischemic myocardial damage. Mol Med 17:194–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcasoy MO. (2008) The non-haematopoietic biological effects of erythropoietin. Br J Haematol 141:14–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogoyevitch MA. (2004) An update on the cardiac effects of erythropoietin cardioprotection by erythropoietin and the lessons learnt from studies in neuroprotection. Cardiovasc Res 63:208–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brines M, Cerami A. (2006) Discovering erythropoietin’s extra-hematopoietic functions: biology and clinical promise. Kidney Int 70:246–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brines M, Cerami A. (2008) Erythropoietin-mediated tissue protection: reducing collateral damage from the primary injury response. J Intern Med 264:405–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brines M, Grasso G, Fiordaliso F, Sfacteria A, Ghezzi P, Fratelli M, Latini R, Xie QW, Smart J, Su-Rick CJ, et al. (2004) Erythropoietin mediates tissue protection through an erythropoietin and common beta-subunit heteroreceptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:14907–14912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brines M, Patel NS, Villa P, Brines C, Mennini T, De Paola M, Erbayraktar Z, Erbayraktar S, Sepodes B, Thiemermann C, et al. (2008) Nonerythropoietic, tissue-protective peptides derived from the tertiary structure of erythropoietin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:10925–10930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haiden N, Cardona F, Schwindt J, Berger A, Kuhle S, Homoncik M, Jilma-Stohlawetz P, Pollak A, Jilma B. (2005) Changes in thrombopoiesis and platelet reactivity in extremely low birth weight infants undergoing erythropoietin therapy for treatment of anaemia of prematurity. Thromb Haemost 93:118–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heij L, Niesters M, Swartjes M, Hoitsma E, Drent M, Dunne A, Grutters JC, Vogels O, Brines M, Cerami A, et al. (2013) Safety and efficacy of ARA 290 in sarcoidosis patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a randomized, double-blind pilot study. Mol Med 18:1430–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettrick DA, Pagel PS, Kersten JR, Lowe D, Warltier DC. (1997) The effects of isoflurane and halothane on left ventricular afterload in dogs with dilated cardiomyopathy. Anesth Analg 85:979–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato S, Amano H, Ito Y, Eshima K, Aoyama N, Tamaki H, Sakagami H, Satoh Y, Izumi T, Majima M. (2010) Effect of erythropoietin on angiogenesis with the increased adhesion of platelets to the microvessels in the hind-limb ischemia model in mice. J Pharmacol Sci 112:167–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkeby A, Torup L, Bochsen L, Kjalke M, Abel K, Theilgaard-Monch K, Johansson PI, Bjørn SE, Gerwien J, Leist M. (2008) High-dose erythropoietin alters platelet reactivity and bleeding time in rodents in contrast to the neuroprotective variant carbamyl-erythropoietin (CEPO). Thromb Haemost 99:720–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koul D, Dhar S, Chen-Scarabelli C, Guglin M, Scarabelli TM. (2007) Erythropoietin: new horizon in cardiovascular medicine. Recent Patents Cardiovasc Drug Discov 2:5–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latini R, Brines M, Fiordaliso F. (2008) Do non-hemopoietic effects of erythropoietin play a beneficial role in heart failure? Heart Fail Rev 13:415–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leist M, Ghezzi P, Grasso G, Bianchi R, Villa P, Fratelli M, Savino C, Bianchi M, Nielsen J, Gerwien J, et al. (2004) Derivatives of erythropoietin that are tissue protective but not erythropoietic. Science 305:239–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippi G, Franchini M, Favaloro EJ. (2010) Thrombotic complications of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents. Semin Thromb Hemost 36:537–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsic E, Schoemaker RG, van der Meer P, Voors AA, van Veldhuisen DJ, van Gilst WH. (2006) Protective effects of erythropoietin in cardiac ischemia: from bench to bedside. J Am Coll Cardiol 48:2161–2167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madonna R, Shelat H, Xue Q, Willerson JT, De Caterina R, Geng YJ. (2009) Erythropoietin protects myocardin-expressing cardiac stem cells against cytotoxicity of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Exp Cell Res 315:2921–2928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey RP, Czer L, Shah PK. (2011) Chronic heart failure: current evidence, challenges to therapy, and future directions. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 11:153–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder P, Devaux B, Richard V, Henry JP, Wimart MC, Thibout E, Macé B, Thuillez C. (1997) Early versus delayed angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in experimental chronic heart failure. Effects on survival, hemodynamics, and cardiovascular remodeling. Circulation 95:1314–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair AP, Timoh T, Fuster V. (2012) Contemporary medical management of systolic heart failure. Circ J 76:268–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niesters M, Swartjes M, Heij L, Brines M, Cerami A, Dunne A, Hoitsma E, Dahan A. (2013) The erythropoietin-analogue ARA 290 for treatment of sarcoidosis-induced chronic neuropathic pain. Exp Opin Orphan Drugs 1:77–87 [Google Scholar]

- Nonnast-Daniel B, Creutzig A, Kühn K, Bahlmann J, Reimers E, Brunkhorst R, Caspary L, Koch KM. (1988) Effect of treatment with recombinant human erythropoietin on peripheral hemodynamics and oxygenation. Contrib Nephrol 66:185–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie M, Yu X, Nicolas-Metral V, Pulido SM, Liu C, Ruegg UT, Noguchi CT. (2000) Erythropoietin stimulates proliferation and interferes with differentiation of myoblasts. J Biol Chem 275:39754–39761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivetti G, Quaini F, Lagrasta C, Ricci R, Tiberti G, Capasso JM, Anversa P. (1992) Myocyte cellular hypertrophy and hyperplasia contribute to ventricular wall remodeling in anemia-induced cardiac hypertrophy in rats. Am J Pathol 141:227–239 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer JM, Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E. (1987) Hemodynamic benefits and prolonged survival with long-term captopril therapy in rats with myocardial infarction and heart failure. Circulation 75:I149–I155 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer MA, Pfeffer JM, Steinberg C, Finn P. (1985) Survival after an experimental myocardial infarction: beneficial effects of long-term therapy with captopril. Circulation 72:406–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richer C, Fornes P, Cazaubon C, Domergue V, Nisato D, Giudicelli JF. (1999) Effects of long-term angiotensin II AT1 receptor blockade on survival, hemodynamics and cardiac remodeling in chronic heart failure in rats. Cardiovasc Res 41:100–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riksen NP, Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. (2008) Erythropoietin: ready for prime-time cardioprotection. Trends Pharmacol Sci 29:258–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sautina L, Sautin Y, Beem E, Zhou Z, Schuler A, Brennan J, Zharikov SI, Diao Y, Bungert J, Segal MS. (2010) Induction of nitric oxide by erythropoietin is mediated by the beta common receptor and requires interaction with VEGF receptor 2. Blood 115:896–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer RM, Leschke M, Strauer BE, Heidland A. (1988) Blood rheology and hypertension in hemodialysis patients treated with erythropoietin. Am J Nephrol 8:449–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasko J, Galajda P, Ivanková J, Hollý P, Rozborilová E, Kubisz P. (2007) Soluble P-selectin during a single hemodialysis session in patients with chronic renal failure and erythropoietin treatment. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 13:410–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stohlawetz PJ, Dzirlo L, Hergovich N, Lackner E, Mensik C, Eichler HG, Kabrna E, Geissler K, Jilma B. (2000) Effects of erythropoietin on platelet reactivity and thrombopoiesis in humans. Blood 95:2983–2989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri ND. (1999) Mechanism of erythropoietin-induced hypertension. Am J Kidney Dis 33:821–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogiatzi G, Briasoulis A, Tousoulis D, Papageorgiou N, Stefanadis C. (2010) Is there a role for erythropoietin in cardiovascular disease? Expert Opin Biol Ther 10:251–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf RF, Gilmore LS, Friese P, Downs T, Burstein SA, Dale GL. (1997a) Erythropoietin potentiates thrombus development in a canine arterio-venous shunt model. Thromb Haemost 77:1020–1024 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf RF, Peng J, Friese P, Gilmore LS, Burstein SA, Dale GL. (1997b) Erythropoietin administration increases production and reactivity of platelets in dogs. Thromb Haemost 78:1505–1509 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.