Abstract

A number of extracellular stimuli, including soluble cytokines and insoluble matrix factors, are known to influence murine embryonic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation behavioral responses via intracellular signaling pathways, but their net effects in combination are difficult to understand. To gain insight concerning key intracellular signals governing these behavioral responses, we employ a multivariate systems analysis of proteomic data generated from combinatorial stimulation of mouse embryonic stem cells by fibronectin, laminin, leukemia-inhibitory factor, and fibroblast growth factor 4. Phosphorylation states of 31 intracellular signaling network components were obtained across 16 different stimulus conditions at three time points by quantitative Western blotting, and partial-least-squares modeling was used to determine which components were most strongly correlated with cell proliferation and differentiation rate constants obtained from flow cytometry measurements of Oct-4 expression levels. This data-driven, multivariate (16 conditions × 31 components × 3 time points = ≈1,500 values) proteomic approach identified a set of signaling network components most critically associated (positively or negatively) with differentiation (Stat3, Raf1, MEK, and ERK), proliferation of undifferentiated cells (MEK and ERK), and proliferation of differentiated cells (PKBα, Stat3, Src, and PKCε). These predictions were found to be consistent with previous in vivo literature, along with direct in vitro test here by a peptide inhibitor of PKCε. Our results demonstrate how a computational systems biology approach can elucidate key sets of intracellular signaling protein activities that combine to govern cell phenotypic responses to extracellular cues.

Mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells are derived from the inner cell mass of preimplantation blastocysts (1). They are pluripotent and can contribute to every tissue in the adult organism (2). This developmental potential can be maintained in vitro in the presence of the gp130 signaling ligand, leukemia-inhibitory factor (LIF) (3, 4). Binding of LIF to the LIFR-gp130 receptor complex stimulates signaling through two main pathways, the Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) pathway and the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)/extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway (5). The roles of these LIF-stimulated pathways in maintenance of ES cell pluripotency are not completely understood, although activation of Stat3 is indispensable for self-renewal (6, 7). Despite the importance of LIF in murine ES cell self renewal, maintenance of somatic stem cells in vitro has remained elusive, and ES cells from other species, e.g., human, apparently cannot be maintained by the presence of LIF alone (8, 9). Moreover, extracellular matrix factors, such as fibronectin (Fn) and laminin (Ln), can significantly influence the effects of cytokines (10–12).

Cytokines and matrix factors that regulate ES cell processes operate through multiple intracellular signaling pathways, which are generally found across diverse cell types (13). Indeed, cytokines that exert opposite effects on differentiation outcomes can activate similar pathways (14). Conversely, more than one factor may be capable of triggering similar cell responses, as is the case with LIF and IL-6 (15, 16), but the potency of any given factor may depend on the signaling context. As with other cell behavioral responses to cytokine and matrix factors, such as migration and apoptosis, the control of stem cell self-renewal versus differentiation responses most likely depends on the balance among a set of intracellular signaling activities, rather than being uniquely determined by one particular component. Although two new ES cell-specific regulatory transcription factors have been recently identified, Ehox and Nanog (17–19), it remains important to address the question of how the expression of transcription factors is regulated by extracellular cues through intracellular signals.

An urgent question is: how can a critical set of intracellular signaling network activities be identified for governing stem cell self-renewal versus differentiation responses across a broad spectrum of extracellular cytokine and matrix cues? For instance, we study here Oct-4 expression levels in mouse ES cells after treatment with 16 different conditions, for three time points over 5 days, comprising permutations of cytokine [LIF and fibroblast growth factor 4 (FGF-4)] and matrix factor (Fn and Ln) combinations. Because so few signaling pathways have been explored in relation to this important problem, especially across cytokine/matrix combinations, a “data-driven” approach, analogous to the now-common transcriptional profiling methods for studies directed to genomic issues, is an attractive initial step. Because we are concerned with protein signaling network activities governing cell behavior, protein-level measurements involving multiple pathways must be made and analyzed. Therefore, we use quantitative Western blotting to obtain levels of 31 phospho-proteins involved in more than a half-dozen signaling pathways. Finally, many computational modeling techniques often used for genomic investigations, such as clustering, are not appropriate for the multivariate statistical dependence analysis needed to elucidate combinations of signals most strongly associated with cell behavioral responses. Accordingly, we bring a partial-least-squares (PLS) multivariate modeling technique to bear on our set of 16 × 31 × 3 = 1,488 cue–signal–response measurement values. This approach yields, in entirely data-driven manner, a set of seven phospho-proteins (Stat3, Raf1, MEK, ERK, Src, PKCε, and PKBα) most critically associated with cell differentiation rates and/or proliferation rates. Many of these predictions are found to be consistent with previous literature reports or new experimental tests we conduct here. Overall, we have successfully demonstrated a data-driven multivariate proteomic analysis for gaining insights into cue–signal–response relationships underlying stem cell self-renewal versus differentiation processes. This approach should be generally applicable to analogous studies of other cell types and other behavioral processes.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines. CCE ES cells were maintained by standard techniques for feeder-free cultures. Serum containing medium supplemented with 500 pM LIF (Chemicon) was replaced every 24 h, and cells were passaged every 48 h. Cells were stored in liquid nitrogen and used within 10 passages of thawing.

Cell Growth Experiments. Flasks were coated with matrix protein by adding a solution of the substrate and incubating overnight at 4°C. Twenty-four hours prior to an experiment, cells were fed serum-free medium (identical to ES maintenance medium except serum is replaced with 15% Knockout Serum Replacement from GIBCO). On day 0, cells were harvested with trypsin that was quenched with serum-free medium plus 1.5 mg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor (Sigma) to avoid stimulation with serum. Cells were seeded into flasks with the desired matrix substrate and serum-free medium supplemented with the desired growth factors that was replaced every 48 h. Seeding density was adjusted depending on which day the flask would be harvested. Medium with FGF-4 was supplemented with 1 ng/ml heparin salt. Recombinant human FGF-4, heparin salt, and human plasma Fn were obtained from Sigma. Ln-1 was obtained from BD Biosciences. Myristoylated PKCε V1–2 translocation inhibitor peptide (20) was obtained from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA).

Intranuclear Oct-4 Assay. Intranuclear Oct-4 detection was performed on a single-cell basis across experimental cell populations via fluorescence flow cytometry as described (21, 22), except that the F(ab′)2 fragment of anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes) was used to detect the primary antibody.

Proteomic Analysis. Cells were seeded and cultured exactly as for the fluorescence experiments. Cells were lysed directly in the flasks by using a cell scraper and standard cell lysis buffer. The lysates were centrifuged for 1 h at 4°C and 30,000 × g. Measurements of phosphorylated proteins were performed by Kinexus (Vancouver), using KPSS-1 Western blot analysis.

Statistical Analysis and Computational Modeling. The percentage of differentiated (Oct-4-) cells was evaluated by fitting normal distributions to the peaks in the fluorescence flow cytometry profiles and calculating the area under the normal curve (22). Analysis of the results of the factorial experiment was done by using minitab statistical software (Minitab, State College, PA). Main effects, two-factor interactions, and three-factor interactions, along with the statistical significance of each of these properties, were calculated according to standard factorial analysis formulae (22, 23). PLS analysis of the protein data were performed by using the simca-p software package by Umetrics (Kinnelon, NJ); details can be found in ref. 24.

Results

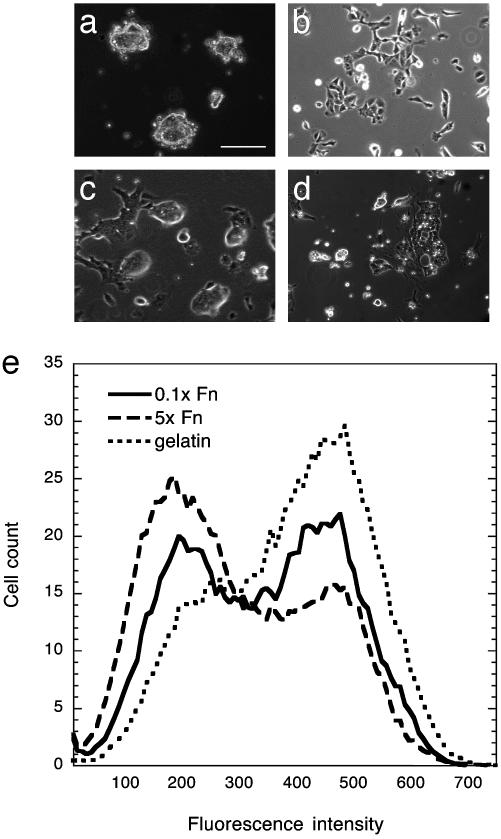

Extracellular Matrix Factors and Cytokines Influence ES Cell Responses in a Complex, Synergistic Manner. We sought first to determine how ES cell self-renewal versus differentiation responses are affected by diverse combinations of extracellular matrix factors and cytokines across a spectrum of permutations. Serum-free medium was used to eliminate interactions with unknown serum factors and deposition of matrix components contained in the serum. Knockout Serum Replacement from GIBCO contains primarily serum albumin with insulin being the only potentially confounding factor. This represents as neutral a background as possible for these experiments. Initial experiments showed that ES cells have diverse morphologies on various purified extracellular matrix (ECM) components in the absence of LIF (Fig. 1 a–d). These matrices influence the extent of differentiation, which can be quantified by measuring the intracellular levels of Oct-4 (Fig. 1e), a transcription factor expressed in the nucleus of pluripotent cells of the early embryo or ES cells derived from these early embryos (25, 26). Down-regulation of Oct-4 expression marks the initial commitment to differentiate.

Fig. 1.

Purified ECM components have measurable effects on ES cell differentiation. (a–d) Light micrographs of cells grown for 2 days in serum-free medium have strikingly different morphologies. (a) Ln-1. (b) Fn. (c) Collagen IV. (d) Gelatin with 500 pM LIF. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (e) Fluorescence histograms for cells grown for 4 days on low-density Fn, high-density Fn, or gelatin and labeled for intranuclear Oct-4.

To explore effects of a spectrum of extracellular cue combinations, and to detect synergies among these factors, we used a 24 full factorial design and a 23 full factorial design for our measurements of Oct-4 expression. We tested 500 pM LIF, 1 ng/ml FGF-4, 40 μg/ml Fn, and 40 μg/ml Ln for the 24 design and FGF-4, Fn, and Ln for the 23 design. The 24 design was dominated by the strong effects of LIF, whereas the 23 design allowed us to detect more subtle effects. We cultured the cells in all 16 combinations of factors in serum-free medium and determined the percentage of differentiated cells on days 2, 3, and 5 by detecting the intracellular levels of Oct-4.

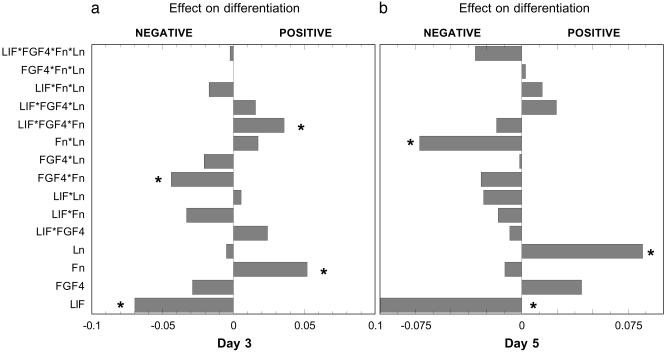

Analysis of the “main effect” of each factor individually, as well as “two-factor effects” and “three-factor effects,” on the percentage of Oct-4- differentiated cells on each day was done by standard statistical methods for analyzing factorial experiments (22, 23) (Fig. 2). As expected, LIF had a strong negative influence on the appearance of differentiated cells throughout the time course. Fn had a large positive effect on differentiated cell number at day 3 but only a small, negative effect at day 5; these effects are directly proportional to the concentration of Fn (22). In contrast, Ln had little effect at day 3 but showed a great positive effect on differentiation by day 5. Although FGF-4 had little effect on its own, it appeared to shift the effect of Fn toward a more antidifferentiation influence (sharply for day 3 and only mildly for day 5). Yet more intriguingly, the combination of FGF-4 and Fn, in turn, appeared to shift the effect of LIF away from antidifferentiation (in fact, to prodifferentiation on day 3 and to lesser antidifferentiation on day 5). Obviously, one cannot predict the overall effects of cytokine and matrix combinations directly from their individual influences. Thus, one must turn to the intracellular signaling pathways activated by these extracellular cues.

Fig. 2.

Factorial analysis of the effects and synergies of extracellular factors on ES cell differentiation. Differentiation was measured by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of Oct-4 expression. The abscissa indicates the effects of each factor, either individually (main effect) or in combinations (two-factor effects and three-factor effects), on the outcome, in terms of positive or negative relative deviations from a null effect, 0, according to standard factorial analysis formulae (23, 24). Statistical significance was determined for each of the main, two-factor, and three-factor effects by comparison to pooled estimate of overall run variance (23, 24); effects significant beyond a standard deviation are marked with an asterisk. (a) Cells were grown for 3 days in 16 combinations of four different factors: 500 pM LIF, 10 ng/ml FGF-4, 2.5 μg/cm2 Fn, and 2.5 μg/cm2 Ln-1. (b) Cells were grown for 5 days in 16 combinations of same four factors.

Multiple Intracellular Signaling Pathways Correlate with Treatment Conditions and Cell Responses. In previous work, we have developed a simple mathematical model describing the kinetics of cell proliferation and differentiation processes, determined by Oct-4 expression levels and total cell numbers measured by flow cytometry (22). This model permits deconvolution of the experimental data (such as that shown in Fig. 1) in terms of cell proliferation rate constants [for both undifferentiated (Gu) and differentiated (Gd) populations] and conversion rate constants [Gc; from undifferentiated to differentiated]. We thus obtained values of Gu, Gc, and Gd for each of the treatment conditions above, based on the cell numbers and fraction of differentiated cells determined on days 0, 2, 3, and 5 (Table 1).

Table 1. Growth parameter calculations for seven different growth conditions.

| Growth condition | Gd | Gu | Gc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fn | 0.88 ± 0.14 | 0.71 ± 0.05 | 0.079 ± 0.026 |

| Ln | 1.52 ± 0.13 | 0.47 ± 0.06 | 0.006 ± 0.001 |

| Gelatin + FGF-4 | 1.40 ± 0.08 | 0.68 ± 0.06 | 0.015 ± 0.005 |

| Fn + FGF-4 | 1.01 ± 0.48 | 0.51 ± 0.07 | 0.044 ± 0.041 |

| Ln + FGF-4 | 0.89 ± 0.09 | 0.60 ± 0.05 | 0.088 ± 0.049 |

| Gelatin + LIF | 0 | 0.83 ± 0.06 | 0 |

| Fn + LIF | 0 | 0.71 ± 0.15 | 0 |

Units are days-1, and values are reported as mean ± SD for two independent experiments.

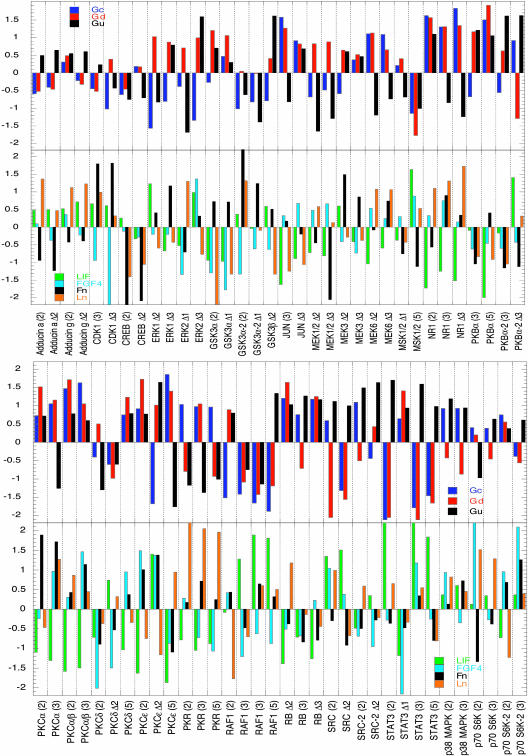

For the present study, then, our aim was to ascertain how these cell response parameters correlated with the levels of phosphorylation of 40 different sites on 31 signaling proteins across the full set of 16 treatment conditions. We used PLS analysis to rank the relationship between outcome and activated intermediates and between extracellular cues and activated intermediates; see ref. 24 for a more complete discussion of PLS application in cell signaling. In our analysis, we included both the absolute levels of each phosphorylated species and the change in levels between each time point. We were able to identify proteins whose activity strongly correlated with cell responses or specific extracellular cues. A partial set representing the most significant regression coefficients are summarized in Fig. 3, for both the cue–signal relationships and the signal–response relationships. The full data sets, including a listing of all the protein phosphorylation sites, are provided in Data Sets 1 and 2, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Fig. 3.

Extracellular cues and growth rates can be correlated to intracellular signaling activities. Regression coefficients were calculated by using PLS analysis for a panel of phosphorylated signaling proteins. The most significant set of coefficients for correlation of phosphoprotein levels to Gc, Gd, and Gu and the extracellular cues (LIF, FGF-4, Fn, and Ln) are shown. Numbers in parentheses represent level on that day. Δ1, difference in levels between days 2 and 3; Δ2, difference in levels between days 2 and 5; Δ3, difference in levels between days 3 and 5.

Fig. 3 reveals consistency of our model predictions with at least one well known signal previously shown to be involved in ES cell self-renewal, Stat3 activity (S727 phosphorylation). Our analysis predicts that Stat3 S727 phosphorylation level is positively correlated with LIF across most time points, and is positively correlated to Gu and negatively correlated to Gc and Gd, as expected.

A number of other signaling components were also indicated to exhibit similarly strong correlation with cell responses across the treatment condition set, in a complex manner. The conversion rate constant for undifferentiated cells to differentiated cells, Gc, is relatively strongly negatively correlated with changes in ERK activation (T202/Y204 phosphorylation on ERK1, and T185/Y187 phosphorylation on ERK2), and mildly negatively correlated with changes in MEK activation (S221/S225 phosphorylation on MEK1/2); at the same time, Gc is also strongly negatively correlated with Raf1 inhibition (S259 phosphorylation). Changes in MEK and ERK activation are concomitantly strongly negatively correlated with the undifferentiated cell proliferation rate constant, Gu, and mildly positively correlated with the differentiated cell proliferation rate constant, Gd. Moreover, along with Stat3 activation, Src (Y418 and Y529 phosphorylation) is strongly negatively correlated with the differentiated cell proliferation rate constant, Gd, whereas PKBα activation (T308 and S473 phosphorylation) is strongly positively correlated with Gd. Another notably indicated signal is PKCε, the activity of which (S719 phosphorylation) is positively correlated with Gc and Gd, whereas its correlation with Gu is mixed. Accordingly, the net outcome of mouse ES cell responses across the range of LIF, FGF-4, Fn, and Ln combinations will depend on, at a minimum, the relative activities (and changes therein) of at least these seven signaling network components.

Thus, our multivariate analysis across the broad range of treatment conditions shows that there is no uniquely correlative signal, and therefore not likely a single dominating control point in the self-renewal versus differentiation cell fate “decision” process.

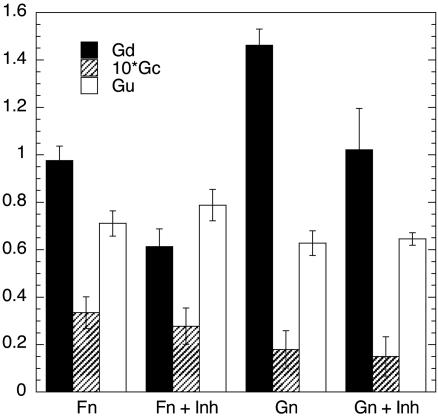

Test of Predicted Effects of PKCε. Many of the predicted correlations outlined above can be validated by reference to previous literature. Among the less widely examined signaling components from the group identified above is PKCε. A recent report by Zhou et al. (20) showed that inhibition of PKCε delayed, but did not abolish, the appearance of differentiated cells (predominantly cardiomyocytes) in embryoid bodies. As noted above, PKCε is predicted by our PLS analysis to be positively correlated with differentiated cell proliferation rate, Gd, and conversion rate, Gc; its correlation with undifferentiated cell proliferation rate, Gu, is mixed. A peptide (20) that prevents the translocation, and therefore the activity, of PKCε was added to cultures of ES cells grown on Fn and on gelatin in the absence of cytokines, and the effects on the three parameters was determined. Fig. 4 shows that this inhibitor indeed substantially diminished Gd, and reduced Gc to a small degree, while having little clear effect on Gu, all as predicted from the PLS model. These cell culture effects are in accord with the in vivo findings of Zhou et al. Although the effects are small quantitatively, it is important to point out that we actually should not necessarily expect anything more dramatic in general; precisely because our multivariate, “systems” analysis emphasizes that any key signaling activity should, indeed, only partially influence the overall cell behavioral response (except perhaps under carefully crafted experimental conditions).

Fig. 4.

Inhibiting PKCε translocation inhibits the growth rate of differentiated cells but not the growth rate of undifferentiated cells. Shown are growth rates of differentiated cells, Gd, growth rate of undifferentiated cells, Gu, and conversion rate of undifferentiated to differentiated cells, Gc, calculated for cultures grown on 40 μg/ml Fn or gelatin in serum-free medium with or without 10 μM PKCε inhibitor (n = 4). Units are days-1, and values are reported as mean ± SD for four independent experiments.

Discussion

Although extracellular cues such as cytokines and matrix factors generate cell behavioral responses such as proliferation, differentiation, migration, and death, it is very difficult to assign simple cue–response relationships in clear and direct manner. Self-renewal versus differentiation responses of ES cells provides one good example of this situation. Although LIF is known as a powerful self-renewal-promoting cytokine for mouse ES cells, when combined with other factors such as extracellular matrix components its effect is not generally predictable. Indeed, as one particular instance, our own experimental results here (Fig. 2) show, quite counterintuitively, that LIF in combination with FGF-4 and Fn acts to promote differentiation. Understanding how combinations of extracellular cues influence regulation of differentiation versus self-renewal is essential to both fundamental scientific understanding and development of technological applications of ES cells. Intracellular protein signaling pathways represent a more proximal locus of governance for cell behavioral functions, so our premise is that signal–response relationships must be sought to better interpret apparent cue–response effects. Moreover, these signaling networks must be studied in multivariate mode, because no individual signaling activity is likely to be uniquely crucial for governing a cell behavioral response. Accordingly, in this work we have demonstrated a data-driven, multivariate proteomic analysis of key intracellular signals governing mouse ES cell responses to combinations of cytokines and matrix factors. We used PLS analysis (24) to identify the set of signaling molecules most strongly correlated with cell proliferation and differentiation rate constants obtained from flow cytometry measurements of Oct-4 expression levels and total cell numbers.

By using this methodology, a set of seven signaling components were found to exhibit especially strong correlation with cell responses across the treatment condition set of LIF, FGF-4, Fn, and Ln combinations, in multivariate fashion. The Stat3 phosphorylation level is positively correlated with Gu and negatively correlated to Gc and Gd, as should be expected from its role in promoting self-renewal (27). On the other hand, MEK and ERK activation are positively correlated with Gd but negatively correlated with Gc and Gu, and PKBα activation is positively correlated with Gd; these associations are largely expected from the appreciated role of these two pathways in promoting differentiation (27). At the same time, our PLS analysis suggests that Gc is also negatively correlated with Raf1 inhibition, a finding that seems to be in contradiction to the MEK/ERK effects; however, this distinction could arise from a separation of ERK-mediated and non-ERK-mediated effects of Raf1 (28).

Another indicated signal is PKCε, which activity (S719 phosphorylation) we have predicted from PLS analysis (Fig. 3) to be positively correlated with differentiated cell proliferation rate, Gd. PKCε is a novel PKC isoform that is involved in both differentiation and adhesion signaling (29–31). Ivaska et al. (31) showed that cell adhesion is required for efficient activation of PKCε by cytokine stimulation, pointing to PKCε as a potential point of integration between cytokine and adhesion signaling. Because the factorial analysis showed that adhesion to Fn increased differentiation, PKCε activity could be involved in this phenomenon. Our experimental verification that inhibition of PKCε activity substantially diminishes Gd (Fig. 4) is consistent with the report by Zhou et al. (20) that PKCε inhibition delayed but did not abolish the appearance of cardiomyocytes in embryoid bodies.

One important point inherent in Fig. 4 should be raised explicitly here: when multiple signaling components are indicated to have significant influence on cell responses, when tested individually (e.g., by inhibitors), each signaling component should most likely only be found to have a small effect for the general set of conditions under consideration. This is, indeed, precisely a key distinction between a “systems biology” perspective and a more traditional “reductionist” perspective. In the latter, dramatic effects of a single component within a system can be found by constructing experimental conditions for which the influence of that component is especially sharply featured. In the former, this sort of dramatization is not an objective, because a crucial insight of systems biology is that cell functions depend in an integrated manner on interactions among multiple components, each contributing a small but significant effect to the overall system operation.

Matrix factors and synergy between matrix and cytokine cues have been shown to influence many developmental processes. In embryonic development, Ln is expressed in the embryo before implantation and is required for successful assembly of the basement membrane that separates the primitive endoderm from the inner cell mass (32). Expression of Ln subunits at this stage requires FGF receptor (FGFR) signaling and addition of Ln to the culture medium of embryoid bodies deficient in FGFR signaling restores normal development (33). In vitro, synergy between matrix signaling (Fn) and cytokine signaling (stem cell factor) are required for development of fully differentiated melanocytes (34). Of most relevance to this work is the observation that feeder-free cultures of human ES cells can only be maintained on Ln (35). However, even on Ln, fibroblast-conditioned medium is still necessary, pointing to a dual requirement of soluble and adhesion signaling. Our analysis demonstrates that matrix components can regulate differentiation processes and act synergistically with soluble signals. The finding that adhesion to Ln reduces differentiation is consistent with the report that parietal endoderm cells in the early embryo differentiate when they lose contact with the Ln-rich basement membrane (36). It remains to be determined whether the synergy observed between FGF-4 and Fn is a coordination of effects on the level of intracellular signaling or whether the physical interaction of the FGFR coreceptor heparin with the heparin-binding domains of Fn enhanced FGF-4 signaling (37, 38). The observation that LIF does not decrease differentiation in the presence of certain combinations of other cues indicates that the regulation of differentiation via gp130 requires a specific context. LIF has been shown to activate both the Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) pathway and the MAPK cascades. Mutagenesis studies have shown that only the JAK/STAT pathway is required for efficient self-renewal, but high levels of gp130 signaling had detrimental effects in cells that could not activate ERK1/2 in response to LIF (39). This may be linked to the finding in other cell types that ERK activation specifically down-regulates the LIFR receptor by phosphorylating it and targeting it for degradation (40, 41). The role of LIF signaling depends on the balance of multiple pathways including the negative feedback of the ERK cascade.

An intriguing observation from our parameter determination studies is that the growth rate of undifferentiated cells seems to be relatively independent of the extracellular environment. This is consistent with the finding that ES cells seem to lack the typical G1 to S checkpoint. Normal cells require mitogenic stimuli, usually via the MEK/ERK pathway, to inactivate retinoblastoma protein (Rb) and cross the threshold to S phase (42), but in ES cells, Rb is constitutively hyperphosphorylated and the checkpoint is bypassed (ref. 43; reviewed in ref. 27). Our results indicate that cell cycle regulation does not depend on gp130 signaling because undifferentiated cells in serum-free culture without cytokines had growth rates identical to cultures with LIF. Establishment of the G1/S checkpoint is one of the first events in differentiation and we show that differentiated cell kinetics do depend on extracellular cues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Technical discussions with Keith Duggar and Kevin Janes were greatly helpful. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation Biotechnology Engineering Research Center at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a Whitaker Foundation Graduate Fellowship (to W.P.).

Abbreviations: ERK, extracellular-regulated kinase; ES, embryonic stem; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; Fn, fibronectin; LIF, leukemia-inhibitory factor; Ln, laminin; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; PLS, partial-least-squares.

References

- 1.Brook, F. A. & Gardner, R. L. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 5709-5712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pease, S. & Williams, R. L. (1990) Exp. Cell Res. 190, 209-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith, A. G., Heath, J. K., Donaldson, D. D., Wong, G. G., Moreau, J., Stahl, M. & Rogers, D. (1988) Nature 336, 688-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams, R. L., Hilton, D. J., Pease, S., Willson, T. A., Stewart, C. L., Gearing, D. P., Wagner, E. F., Metcalf, D., Nicola, N. A. & Gough, N. M. (1988) Nature 336, 684-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ernst, M., Oates, A. & Dunn, A. R. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 30136-30143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuda, T., Nakamura, T., Nakao, K., Arai, T., Katsuki, M., Heike, T. & Yokota, T. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 4261-4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raz, R., Lee, C. K., Cannizzaro, L. A., d'Eustachio, P. & Levy, D. E. (1999). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 2846-2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomson, J. A., Itskovitz-Eldor, J., Shapiro, S. S., Waknitz, M. A., Swiergiel, J. J., Marshall, V. S. & Jones, J. M. (1998) Science 282, 1145-1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reubinoff, B. E., Pera, M. F., Fong, C. Y., Trounson, A. & Bongso, A. (2000) Nat. Biotechnol. 18, 559-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amit, M., Shariki, C., Margulets, V. & Itskovitz-Eldor, J. (2003) Biol. Reprod., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Xu, C., Inokuma, M. S., Denham, J., Golds, K., Kundu, P., Gold, J. D. & Carpenter, M. K. (2001) Nat. Biotechnol. 19, 971-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czyz, J. & Wobus, A. M. (2001) Differentiation 68, 167-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Puijenbroek, A., van der Saag, P. T. & Coffer, P. J. (1999) Exp. Cell Res. 251, 465-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Megeney, L. A., Perry, R. L., LeCouter, J. E. & Rudnicki, M. A. (1996) Dev. Genet. 19, 139-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nichols, J., Chambers, I. & Smith, A. (1994) Exp. Cell Res. 215, 237-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshida, K., Chambers, I., Nichols, J., Smith, A., Saito, M., Yasukawa, K., Shoyab, M., Taga, T. & Kishimoto, T. (1994) Mech. Dev. 45, 163-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson, M., Baird, J. W., Cambray, N., Ansell, J. D., Forrester, L. M. & Graham, G. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 38683-38692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chambers, I., Colby, D., Robertson, M., Nichols, J., Lee, S., Tweedie, S. & Smith, A. (2003) Cell 113, 643-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitsui, K., Tokuzawa, Y., Itoh, H., Segawa, K., Murakami, M., Takahashi, K., Maruyama, M., Maeda, M. & Yamanaka, S. (2003) Cell 113, 631-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou, X., Quann, E. & Gallicano, G. I. (2003) Dev. Biol. 255, 407-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viswanathan, S., Benatar, T., Mileikovsky, M., Lauffenburger, D. A., Nagy, A. & Zandstra, P. W. (2002) Stem Cells 20, 119-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prudhomme, W. (2003) Ph.D. thesis (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge).

- 23.Box, G. E. P. & Hunter, W. G. (1978) Statistics for Experimenters (Wiley, New York).

- 24.Janes, K., Kelly, J., Albeck, J., Gaudet, S., Sorger, P. K. & Lauffenburger, D. A. (2004) J. Comp. Biol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Niwa, H., Miyazaki, J. & Smith, A. G. (2000) Nat. Genet. 24, 372-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nichols, J., Zevnik, B., Anastassiadis, K., Niwa, H., Klewe-Nebenius, D., Chambers, I., Scholer, H. & Smith, A. (1998) Cell 95, 379-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burdon, T., Smith, A. & Savatier, P. (2002) Trends Cell Biol. 12, 432-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dhillon, A. S., Meikle, S., Peyssonnaux, C., Grindlay, J., Kaiser, C., Steen, H., Shaw, P. E., Mischak, H., Eychene, A. & Kolch, W. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 1983-1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ponzoni, M., Lucarelli, E., Corrias, M. V. & Cornaglia-Ferraris, P. (1993) FEBS Lett. 322, 120-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldfarb, A. N., Delehanty, L. L., Wang, D., Racke, F. K. & Hussaini, I. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 29526-29530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ivaska, J., Whelan, R. D., Watson, R. & Parker, P. J. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 3601-3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, S., Harrison, D., Carbonetto, S., Fassler, R., Smyth, N., Edgar, D. & Yurchenco, P. D. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 157, 1279-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, X., Chen, Y., Scheele, S., Arman, E., Haffner-Krausz, R., Ekblom, P. & Lonai, P. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 153, 811-822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takano, N., Kawakami, T., Kawa, Y., Asano, M., Watabe, H., Ito, M., Soma, Y., Kubota, Y. & Mizoguchi, M. (2002) Pigment Cell Res. 15, 192-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu, C., Inokuma, M. S., Denham, J., Golds, K., Kundu, P., Gold, J. D. & Carpenter, M. K. (2001) Nat. Biotechnol. 19, 971-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murray, P. & Edgar, D. (2000) J. Cell Sci. 114, 931-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delehedde, M., Lyon, M., Gallagher, J. T., Rudland, P. S. & Fernig, D. G. (2002) Biochem. J. 366, 235-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ingham, K. C., Brew, S. A. & Atha, D. H. (1990) Biochem. J. 272, 605-611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burdon, T., Stracey, C., Chambers, I., Nichols, J. & Smith, A. (1999) Dev. Biol. 210, 30-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blanchard, F., Duplomb, L., Wang, Y., Robledo, O., Kinzie, E., Pitard, V., Godard, A., Jacques, Y. & Baumann, H. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 28793-28801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blanchard, F., Wang, Y., Kinzie, E., Duplomb, L., Godard, A. & Baumann, H. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 47038-47045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harbour, J. W., Luo, R. X., Dei Santi, A., Postigo, A. A. & Dean, D. C. (1999) Cell 98, 859-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Savatier, P., Huang, S., Szekely, L., Wiman, K. G. & Samarut, J. (1994) Oncogene 9, 809-818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.