Abstract

Background:

Low humidity, high-velocity wind, excessive ultraviolet (UV) exposure, and extreme cold temperature are the main causes of various types of environmental dermatoses in high altitudes.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective study was carried out in patients visiting the lone dermatology department in Ladakh between July 2009 and June 2010. The aim was to identify the common environmental dermatoses in high altitudes so that they can be treated easily or prevented. The patients were divided into three demographic groups, namely, lowlanders, Ladakhis (native highlanders), and tourists. Data was analyzed in a tabulated fashion.

Results:

A total of 1,567 patients with skin ailments were seen, of whom 965 were lowlanders, 512 native Ladakhis, and 90 were tourists. The skin disorders due to UV rays, dry skin, and papular urticaria were common among all groups. The frequency of melasma (n = 42; 49.4%), chronic actinic dermatitis (CAD) (n = 18; 81.81% of total CAD cases), and actinic cheilitis (n = 3; 100%) was much higher among the native Ladakhis. The frequency of cold-related injuries was much lesser among Ladakhis (n = 1; 1.19%) than lowlanders (n = 70; 83.33%) and tourists (n = 13; 15.47%) (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

Dryness of skin, tanning, acute or chronic sunburn, polymorphic light reaction, CAD, insect bite reactions, chilblain, and frostbite are common environmental dermatoses of high altitudes. Avoidance of frequent application of soap, application of adequate and suitable emollient, use of effective sunscreen, and wearing of protective clothing are important guidelines for skin care in this region.

Keywords: Chilblains, dry skin, frostbite, high altitude, ultraviolet rays, Ladakh, papular urticaria

Introduction

What was known?

Peculiar environment of high altitude predisposes non acclimatized person to develop acute mountain sickness, high altitude pulmonary oedema, high altitude cerebral oedema and thrombotic conditions. However, apart from mere few reports of common skin disorders of high altitude area like xerosis, ultraviolet related skin conditions and cold injuries there is no major study on incidence and care of such conditions.

Ladakh—“the land of high mountain passes”—is situated in the northwestern part of India, on the slopes of the Great Himalayas. The ranges of Ladakh, comprising 9,700 sq km, are among the most sparsely populated areas in the world (12 persons per sq km). Leh, the capital city of Ladakh, is situated at an altitude of 3,650 m (12,000 feet). The Ladakh region is known for its scenic beauty, high-peaked mountains covered with snow, glaciers, and peculiar lifestyle of the Buddhist culture that attracts tourists, mountaineers, and trekkers. There is no general consensus on the height from which the high altitude starts; however, a height of 2,700 m and above is considered a working definition of high altitude.[1] Because of extreme height, there are many peculiarities of the environment. The low amount of oxygen, more than three times the exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light than that in the plains, very low humidity (14-20%), subzero temperature in winter (17°C to –30°C), and high velocity of wind (particularly in the afternoon) makes this region difficult for lowlanders as well as for tourists.[2] Acute mountain sickness,[3–5] high-altitude pulmonary edema,[3–6] high-altitude cerebral edema,[3–5] and thromboembolic conditions[7] are known to occur in Ladakh. However, enough knowledge has not been shared on skin ailments peculiar to this region. A study was therefore conducted at the only dermatology center in Ladakh with the aim of determining common environmental dermatoses that can be treated easily or prevented.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective study was conducted of the new dermatology outpatients seen by the author during July 2009-June 2010 at Leh, Ladakh. Data was tabulated as per dermatological disease group and their distribution amongst lowlanders, native Ladakhis, and tourists. Lowlanders were defined as people from the plains who leave this area after about a year (e.g. soldiers, laborers, businessmen, etc.) Only environmental dermatoses related to high altitude such as xerosis, UV-related skin disorders, cold-related injuries, and insect bites were included in the study. Dermatoses that are not specific to the high altitude such as acne vulgaris, psoriasis, vitiligo, keloids, congenital diseases, and bacterial, viral, and fungal infections were excluded from the study.

Results

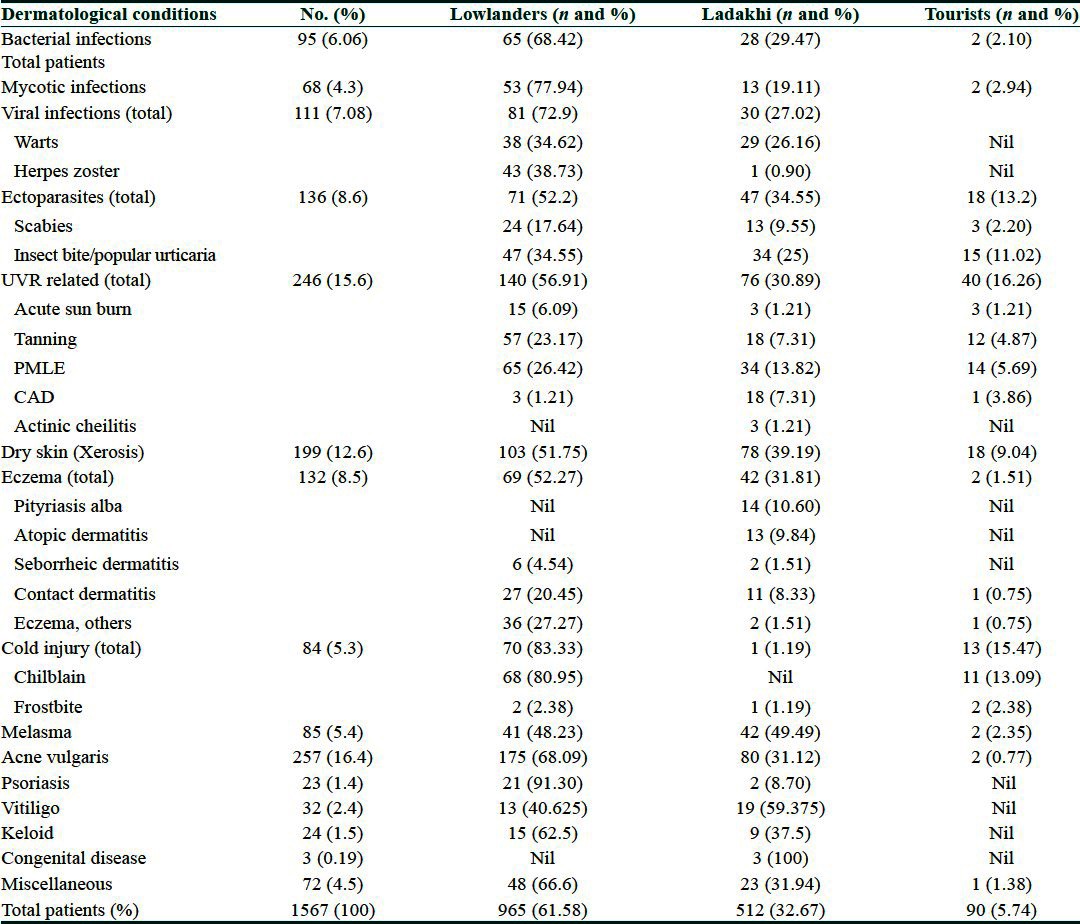

A total of 1,567 new patients with skin ailments related to high altitude were seen. Of these, 965 were lowlanders, 512 native Ladakhis, and 90 were tourists. A detailed distribution of dermatological conditions along with their number and percentage is enumerated in Table 1. Of the four groups of environmental dermatoses, 15.6% (n = 246) of patients had UV-related skin conditions [acute sun burn, melasma, polymorphic light eruption (PMLE), chronic actinic dermatitis (CAD), and actinic cheilitis] followed by xerosis (n = 199, 12.6 %), ectoparasite bites (scabies and insect bite reactions: n = 136, 8.5%), and cold-related injuries (chilblains and frostbite: n = 84, 5.3%).

Table 1.

Distribution of dermatological conditions during July 2009 to June 2010

Native Ladakhis had a much higher incidence of melasma (n = 42, 49.4% of all patients with melasma), CAD (n = 18, 81.81% of all patients with CAD), and actinic cheilitis (n = 3, 100%), when compared to the other two groups. The frequency of cold-related injuries was much lesser among Ladakhis (n = 1, 1.19%) when compared to lowlanders (n = 70, 83.33%) and tourists (n = 13, 15.47%). This was significant with a P value less than 0.05. Only one Ladakhi porter who was working at an altitude of 18,500 feet sustained frostbite.

Discussion

It is estimated that 140 million people over the globe live permanently at altitudes of over 2,500 m and approximately another 40 million enter high-altitude areas every year for reasons of occupation, sports, or recreation. As skin is the largest interface between humankind and the environment, it is one of the targets of the unique, adverse environments ofhigh altitudes. The aim of this study was to determine common environmental dermatoses of high altitudes and their remedial measures.

Xerosis

Low relative humidity and temperature coupled with high velocity of wind causes significant reduction in the water content of the skin.[8–10] Xerosis could lead to pruritus and subsequent cracks, fissuring, and oozing[8] [Figure 1], and hamper daily activities. The ignorant may attribute this to bad hygiene and skin infection, motivating them to use soap or antiseptic liquid in bath water frequently, aggravating the problem. A total of 12.6% of patients had xerosis. Even the native Ladakhis who are accustomed to the weather of this region suffer considerably from xerosis (n = 78, 39.19% of patients with xerosis).

Figure 1.

Dry skin of whole body

How does one avoid dryness at high altitudes? Application of soap should be minimized and if possible, it should be restricted to the face, hands, armpits, and groin. Application of soap to the whole body could be done at fortnightly intervals. Personal experience has shown that soaps having high fatty acid content are better suited for dry weather. Daily bath should be followed by adequate and appropriate application of emollients such as a branded body lotion or oil, preferably coconut or olive oil.[11] Self-medication by way of applying topical steroids or antibiotics over affected areas is harmful, and should always be discouraged.[12]

Similar dryness could develop over the scalp that manifests as fine scaling with itching. This is usually confused with fungal infection, prompting a trial of different brands of antifungal shampoos and treatments that cause further harm to the scalp and hair. Like soap, shampoo should also be used sparingly, preferably once a week. Milder shampoos available in the market may be used, followed by a conditioner.[13] Personal experience in this region has shown that additional weekly application of either coconut or olive oil over the scalp keeps it symptom free.

UV-related skin disorders

Tanning, photomelanosis, acute and chronic sunburn, PMLE, CAD, and actinic cheilitis are common photodermatoses of this region caused by abnormal cutaneous reactions to solar radiation. Although these diseases have different pathophysiologic mechanisms, not all of which have been clearly defined, photoprotection is an integral part of their management. Intensity of UV radiation (UVR) is maximum between 10 AM and 3 PM. Although both UVA (320-400 nm) and B (280-320 nm) are harmful to the skin, it is the UVB component that is responsible for acute skin damage.[14]

Acute sunburn is characterized by sudden-onset redness over the face and exposed parts of the body with or without swelling and pain. If not treated at the appropriate time, it can cause peeling of the skin with oozy lesions [Figure 2]. Prolonged exposure to solar radiation at this altitude can manifest as tanning of exposed areas of the body, mainly the face, the ‘V’ area of the neck, and dorsum of the hands. Patients of PMLE present with itchy, erythematous, and minute grouped papules or plaques over the exposed parts of the body mainly the forearm, nape of the neck, and face [Figure 3]. CAD appears as thick erythematous to hyperpigmented lesions over the exposed areas of the body, the commonest sites being the dorsum of both hands and nape of the neck [Figure 4]. Erosions or ulcers can develop over the lower lip, known as actinic cheilitis [Figure 5].

Figure 2.

Acute sun burn of the back

Figure 3.

Polymorphic light eruption of the neck

Figure 4.

Chronic actinic dermatitis of nape of neck

Figure 5.

Actinic cheilitis of lower lip

There was no significant difference across different groups in the incidence of UVR-related acute conditions such as acute sunburn, tanning, and PMLE. However, the incidence of CAD and actinic cheilitis was higher in the Ladakhis, indicating prolonged exposure to UVR. Melasma and chronic telangiectasia of the face were very common among the native Ladakhis; however, only those who sought dermatological advice for the same were included. Thus, the true incidence of melasma and telangiectasia of the face might be much higher in native Ladakhis than has emerged from this study.

Sun-protective measures should be the first line of treatment. Persons should be encouraged to use wide-brimmed headgear and full-sleeved clothes with restricted outdoor movement between 10 AM and 3 PM and liberal use of broad-spectrum sunscreen with a sun-protection factor (SPF) >30 at least 20 minutes before going out in the sun.[15,16] The SPF value for sunscreens reflects the ability of the product to protect against UV-induced erythema, which is primarily the effect of UVB exposure and to a lesser extent from UVA-2 (320-340 nm). Broad-spectrum sunscreens should have a mixture of organic UVB filters [cinnamates, para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) derivatives, salicylates, ensulizole], organic UVA filters (benzophenone, avobenzone, meradimate), and inorganic filters (titanium dioxide, zinc oxide).[15,16] Unlike other cosmetic products, sunscreen should not be massaged over the face or hands; instead it should be applied by spreading the lotion gently on the surface, preferably over a cold cream in high altitudes. It should be reapplied after 3-4 hours if the person intends to be outdoors for a longer duration of time.

Acute sunburn, polymorphic light reaction, CAD, and actinic cheilitis may require the opinion of a dermatologist for diagnosis and management. Mild to moderate topical steroids, depending upon the area of involvement and severity of lesions, are helpful. Oral vitamin C taken at a dosage of 100 mg daily has been found to be sun protective.[14] CAD usually requires administration of oral steroids or immunosuppressants such as azathioprine.

Cold-related injury (chilblains, frost bite)

In winter, temperatures in Ladakh may dip to −30° C; on glaciers and snow-bound mountains, temperature may dip even to −60° C. If adequate precautions are not been taken against the cold, persons can suffer from chilblains or frostbite. Chilblain is an inflammatory disorder of the skin seen where the skin is exposed to nonfreezing temperatures for a long time, characterized by redness, pain, and itching over the affected areas.[17] It usually affects the tips of toes [Figure 6], fingers, tip of the nose, and ear pinna. It has been found that persons with low body mass index and a genetic predisposition are more likely to develop chilblains.[17,18] All 79 cases of chilblains were seen either in lowlanders (n = 68) or tourists (n = 11) with not a single case among the native Ladakhis (P < 0.005). This could be explained by the genetic makeup of the native Ladakhi and protective lifestyle.

Figure 6.

Chilblain of right hand

Regular care of feet such as soaking in lukewarm water and drying them, application of emollients, and wearing of nylon socks in layers are established precautionary measures against chilblains. Very tight or loose shoes should be avoided.[19] The practice of adding tea leaves and beet to warm water for soaking of the feet in these areas requires scientific analysis. Though the Defence Research and Development Organization (DRDO) of India has introduced nitroglycerine and salbutamol sulfate creams for the prevention of cold injuries after pilot studies on soldiers and workers residing in high altitudes,[20] larger clinical trials are needed to establish their efficacy. The author finds Cutfar, an Ayurvedic cream to be effective in treating chilblains; however, this needs validation by a clinical trial. Oral nifedipine has been found to be effective but should be prescribed under supervision.[21]

Frostbite develops due to prolonged exposure to subzero temperatures and consequent formation of ice crystals in the cells of tissues leading to blister formation.[22] The toes are usually affected [Figure 7]; however, whole feet, fingers, pinna, and tip of the nose may be involved. Coldness, firmness, stinging, burning, numbness, clumsiness, pain, throbbing, or electric current-like sensations on rewarming of the affected areas are the usual complaints of patients. Like in thermal burns, depending upon the severity and duration of exposure, frostbite can be classified into four degrees. First-degree injury is superficial frostbite which involves the epidermis only; this is reversible. When it affects tissues deeper than the epidermis, it is labeled second, third, and fourth degree depending upon the depth. Fourth-degree frostbite is full-thickness damage affecting muscles, tendons, and bone, with resultant tissue loss.[22,23] Salvage of the affected part is very difficult in fourth-degree frostbite and the patient usually requires surgical intervention such as amputation. Surgical consultation should always be sought when there is the formation of multiple bullae, gangrene, loss of tissue, or evidence of infection.[22]

Figure 7.

Frostbite of both the feet

The best preventive measure for frostbite is the wearing of protective clothing. For affected individuals, gradual warming of the affected part of the body (temperature from 37°C to 40-42°C) should be done for half an hour, three to four times daily. Affected areas should not be rubbed or massaged. Analgesics such as diclofenac sodium, ibuprofen, or injection morphine sulfate can be given.[19,22] Such individuals must be deinducted from extreme cold climate to prevent recurrence.

Insect bite reaction (papular urticaria)

Afforestation of barren land at Ladakh has brought ectoparasite insects into the habitat. These insects including ants, wasps, and moths (Hymenoptera spp.) attack aphids (Chaitophorus spp.) which are usually found on the willow trees (Salix spp.). Willow tree around the house bring these insects to moist areas of the house such as the bathroom. Bite marks of these insects cause red raised itchy lesions usually on the exposed parts of the body like forearms, nape of neck, and face [Figure 8]. Papular urticaria is generally regarded to be the result of a hypersensitivity reaction to bites from insects such as mosquitoes, gnats, fleas, mites, bedbugs, caterpillars, moths, and so on.[24,25] There was no significant difference in the incidence of papular urticaria in lowlanders, local Ladakhis, or tourists.

Figure 8.

Papular urticaria of face and neck

Individuals should be careful while working along the roadside where the density of willow trees is high. Bathroom and its surroundings must be sprayed with malathion or pyrethrum at regular intervals. Redness and itching usually subside with the application of calamine lotion and oral antihistamines such as cetirizine. If lesions are extensive, dermatological opinion should be sought, as it might require a prescription of topical and systemic steroids.[26]

Conclusion

Low humidity, high velocity of wind, excessive UV exposure, and extreme cold temperature are the main causes of various types of environmental dermatoses in the high altitudes. Dryness of skin, tanning, acute or chronic sunburn, polymorphic light reaction, CAD, insect bite reactions, chilblain, and frostbite are common environmental dermatoses of this region. Incidence of cold-related injuries was higher among lowlanders and tourists when compared to the native highlanders. There was not much difference in the incidence of other environmental dermatoses. Avoidance of frequent application of soap, application of adequate and suitable oil or body lotion, effective sunscreen, and wearing of protective clothing are important guidelines for skin care in high altitudes. The skin care kit for high-altitude areas would comprise the following: Cold cream, body lotion, coconut or olive oil, sunscreen, large-brimmed hat/cap, UV-protected goggles, vitamin C tablets, and protective warm clothing including gloves and socks. Daily skin care is thus essential for preventing environmental dermatoses in high-altitude areas.

What is new?

Dryness of skin, tanning, acute or chronic sunburn, polymorphic light reaction, chronic actinic dermatitis, insect bite reaction, chilblains and frostbite are common environmental dermatoses of this region. Incidence of cold injuries in locals are almost negligible which is statistically significant. Knowledge of daily skin care and preventive measures hold the key in the management of such conditions

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Director General Armed Forces Medical Service. Medical Memoranda in Problems of High Altitude. 1997;140:31–2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.West JB. The Atmosphere. In: Hornbein TF, Schoene RB, editors. High Altitude an Exploration of Human Adaptation. Vol. 161. New York: Mercel Dekker Inc; 2001. pp. 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basnyat B, Murdoch DR. High-altitude illness. Lancet. 2003;361:1967–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13591-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hackett PH, Roach RC. High-altitude illness. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:107–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hackett PH, Roach RC. High-altitude medicine. In: Auerbach PS, editor. Wilderness medicine. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 2001. pp. 2–43. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hultgren HN. High-altitude pulmonary edema: Current concepts. Annu Rev Med. 1996;47:267–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.47.1.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anand AC, Jha SK, Saha A, Sharma V, Adya CM. Thrombosis as a complication of extended stay at high altitude. Natl Med J India. 2001;14:197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pons-Guiraud A. Dry skin in dermatology: A complex physiopathology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blank I. Further observations on factors which influence the water content of the stratum corneum. J Invest Dermatol. 1953;21:259–71. doi: 10.1038/jid.1953.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engelke M, Ensen JM, Ekanayake-Mudiyanselage S, Proksche E. Effects of xerosis and ageing on epidermal proliferation and differentiation. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:219–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1997.18091892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siddappa K. Dry skin conditions, eczema and emollients in their management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harding, Watkinson, Rawlings, Scott Dry skin, moisturization and corneodesmolysis. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2000;22:21–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-2494.2000.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drovetskaya TV, Kreeger RL, Amos JL, Davis CB, Zhou S. Effects of low-level hydrophobic substitution on conditioning properties of cationic cellulosic polymers in shampoo systems. J Cosmet Sci. 2004;55:195–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawk JL, Young AR, Ferguson J. Cutaneous Photobiology. In: Burn T, Breathnach S, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. Vol. 2. United States: Blackwell Publishing; 2004. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Draelos ZD, Lim HW, Rougier A. Sunscreens and photodermatoses. In: Lim HW, Draelos ZD, editors. Clinical guide to sunscreens and photoprotection. New York: Informa Healthcare; 2008. pp. 83–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deleo V. Sunscreen use in photodermatoses. Dermatol Clin. 2006;24:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goette DK. Chilblains. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:257–62. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70209-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeGroot DW, Castellani JW, Williams JO, Amoroso PJ. Epidemiology of U.S. Army cold weather injuries, 1980–1999. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2003;74:564–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cappaert TA, Stone JA, Castellani JW, Krause BA, Smith D, Stephens BA. National Athletic Trainers’ Association Position Statement: Environmental Cold Injuries. J Athl Train. 2008;43:640–58. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.6.640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rustin MH, Newton JA, Smith NP, Dowd PM. The treatment of chilblains with nifedipine: The results of a pilot study, a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized study and a long term open trial. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:267–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1989.tb07792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brochure-DRDO. Available from: http://www.drdo.gov.in/drdo/labs/INMAS/collaboration/brochure.htm .

- 22.Murphy JV, Banwell PE, Roberts AHN, McGrouther DA. Frostbite: Pathogenesis and treatment. J Trauma. 2000;48:171–8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200001000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCauley RL, Smith DJ, Jr, Robson MC, Heggers JP. Frostbite and other cold-induced injuries. In: Auerbach PA, editor. Wilderness Medicine: Management of Wilderness and Environmental Emergencies. 3rd ed. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 1995. pp. 129–45. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stibich AS, Schwartz RA. Papular urticaria. Cutis. 2001;68:89–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demain JG. Papular urticaria and things that bite in the night. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2003;3:291–303. doi: 10.1007/s11882-003-0089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howard R, Frieden IJ. Papular urticaria in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:246–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1996.tb01212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]