Abstract

American recognition for medical pluralism arrived in 1991. The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine was established under the National Institutes of Health in 1998. Following this, patients and researchers began exploring use of integrative medicine. Terence Ryan with Gerry Bodeker in Europe, Brian Berman in America, and the Indian council of Medical Research advocated traditional medicine and integrative medicine. The Institute of Applied Dermatology (IAD), Kerala has developed integrated allopathic (biomedical) and ayurvedic therapies to treat Lymphatic Filariasis, Lichen planus, and Vitiligo. Studies conducted at the IAD have created a framework for evidence-based and integrative dermatology (ID). This paper gives an overview of advances in ID with an example of Lichen Planus, which was examined jointly by dermatologists and Ayurveda doctors. The clinical presentation in these patients was listed in a vikruthi table of comparable biomedical terms. A vikruthi table was used for drug selection in ayurvedic dermatology. A total of 19 patients were treated with ayurvedic prescriptions to normalize the vatha-kapha for 3 months. All patients responded and no side effects were recorded. In spite of advancing knowledge on ID, several challenges remain for its use on difficult to treat chronic skin diseases. The formation of new integrative groups and financial support are essential for the growth of ID in India.

Keywords: Ayurveda, complementary and alternative medicine, integrative dermatology, integrative medicine, lichen planus, medical pluralism, traditional medicine, vikruthi table

Introduction

Despite millennia of existence, American approval for nonallopathic systems of medicine arrived only in 1991. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) established its ‘Office of Alternative Medicine’ (1991) and initiated a National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (1998).[1] To explore the possibility of integrating other systems of medicine with allopathy, Brian Berman, a family physician and now Cochrane collaborator for complementary and alternative medicines (CAM), founded the Center for Integrative Medicine (1991). This inter-departmental university center, within the University of Maryland School of Medicine, was the first to focus on integrating Chinese medicine with allopathy (biomedicine). Other Universities such as Arizona and other Institutes of Integrative Medicine followed this example.[2] In 2001, the British Medical Journal (BMJ) began a debate on integrative medicine. Lesley Rees and Andrew Weil in their editorial defined integrative medicine as ‘practicing medicine in a way that selectively incorporates elements of complementary and alternative medicine into comprehensive treatment plans alongside biomedical methods of diagnosis and treatment’.[3] Richard Nahin, a psychologist and senior advisor to the NIH, joining the debate in the BMJ, said the full spectrum of studies using CAM can be done without identifying underlying the mechanism of action of each intervention provided there is a clear clinically relevant endpoint.[4] He argued that if the patient improves with very clear outcome measures then CAM should be recommended for use. Terence Ryan, as Chairman of the International Foundation of Dermatology, advocated Skin Care for All.[5] As over 60% of world population depended on CAM for their routine health care, Ryan thought that especially in wound healing, CAM should be explored.[6] By this, patients can benefit from the best practices in biomedicine and CAM without losing anything in the process. This concept of integration has been welcomed by patients and a few leaders in medicine.[7]

Indian Studies

India has over 100 systems of traditional medical systems, Ayurveda, Yoga, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy (AYUSH) being the major healthcare systems. The Government of Kerala reserves places on medical courses for graduates of Ayurveda, homeopathy, and allopathy medicine; so that they learn about other systems.[8] In Kerala, those who are trained in more than one system of medicine are known as multi-speciality doctors. However, the Government has not initiated any special programs to make use of this rare expertise. Most of these doctors generally practice one system of medicine and rarely show interest in research. Since 2000, there have been very few senior medical faculty in India's leading academic institutions who are aware of the benefits of CAM particularly Ayurveda.[9] Department of Health Research, Government of India (DHR) developed a policy for studies on Ayurveda and other traditional medicines. This reduced the regulatory requirements for clinical evaluations of formulations in Ayurveda, which may later be used in Ayurveda hospitals. This is particularly on testing for toxicity in animals, if they are already in use in practice or described in Ayurveda texts.[10] Furthermore, no toxicity study will be required for a Phase II trial. This is the unique reverse pharmacology approach applied in the evaluation of traditional formulations for traditional indications.[11] This approach was first publicized by a multi-speciality expert Dr. Satyavathi a former Director General of DHR.[12]

Now DHR supports an advanced center for reverse pharmacology in traditional medicine at Sevagram.[13] Valiathan, a cardiologist and Muthuswamy, a senior official in the Department of Health led the formulation of these guidelines for the Government.[10] The late Prof S.A. Dahanukar, Pharmacologist and dean at KEM Hospital, Bombay introduced Ayurveda in her best seller, Ayurveda Unravelled.[14] Other islands of activity in traditional medicine, with a focus to develop new drugs, occur in the Indian Institute of integrative medicine at Jammu and Ayurgenomic studies of Maithili Mukargee.[15] Urmila Thatte is leading molecular studies on Ayurveda using leads from allopathy sector in her laboratory at G S Seth Medical College, Mumbai. She is promoting evidence-based Ayurveda through her International Journal of Ayurveda Research. Shirley Telles, an allopathy doctor took up the chair of ICMR centre for advanced studies in Yoga.[13] With her association, Pathanjali Yoga Peet at Haridwar and S-VYASA Yoga University, Bangalore have produced over 100 high quality publications on yoga breathing and exercises. Recently a vaidya-scientist fellowship program was launched to train group leaders who might bridge medical systems with the required evidence base.[16]

Medical Pluralism to Integration

In spite of the above activities with several years of funding for traditional medicine research, integration of therapies has not been achieved at the bedside of patients. Although literature on effectiveness and safety of CAM is gradually increasing, different systems of medicine remained compartmentalized. This may be because researchers have focused more on laboratory experiments to explore the molecular basis of traditional medicine and less at the clinical level. Medical journals have a publication bias toward quantitative medical research, rather than with qualitative medical research.[17] Integrative medicine can only evolve through qualitative research, which should later receive funding for quantitative trials such as Randomized control trial (RCT). There is a need to increase awareness among peers that qualitative medical research is not only the territory of social scientists, but also a prerequisite for quantitative research in allopathy.[18] Qualitative research is slowly occupying the centre stage within the Evidence-Based Medicine movement.

Therefore an emphasis focused on clinical evaluations of traditional formulation is needed to overcome this barrier.[5] The World Health Organization (WHO) issued guidelines for clinical evaluation of traditional medicines.[19] The Institute of Applied Dermatology (IAD) at Kasaragod, Kerala discussed such methods for clinical evaluation in Ayurveda.[20] Literature searches for articles on Ayurveda posed special challenges, since many of the Indian journals in which such articles appear are not indexed by current medical databases such as PubMed and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. A guideline evolved to enable comprehensive searches to locate all types of Ayurvedic articles, not necessarily only randomized controlled trials.[21] In view of the medical advancement in allopathy and of its often unsafe drugs, to prove benefit requires large numbers. From a public health perspective this should be best based on the most common diseases. The IAD methodology paper on integrative dermatology (ID) using examples of two common diseases, Lymphatic Filariasis and Vitiligo, received worldwide attention.[2]

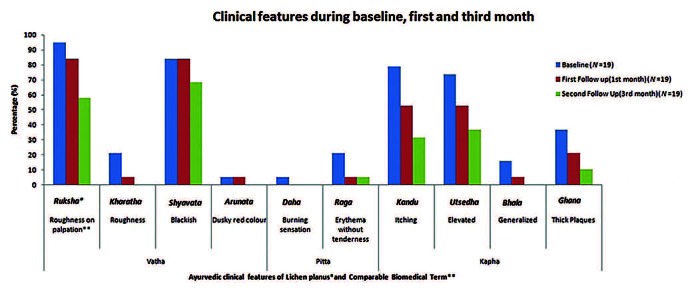

Briefly following are the major steps of integration practiced in IAD. Patients are examined simultaneously, by dermatologist, ayurvedist, yoga therapist, and homeopathic doctors during the first and subsequent follow up visits. Clinical diagnosis is based on allopathy and treatment given is Ayurveda/homeopathy/yoga therapy alongside allopathic treatments. The prescriptions are strictly based on the therapeutic guidelines of respective systems in clinical practice. The outcome measures used are those of allopathy. ID therefore differs from the pattern of laboratory integration that dominates the publically funded research on traditional medicine. This follows the structure of evidence-based dermatology practiced by the International Cochrane Skin Group.[22] This means, systematic searches of literature based on a Population, Intervention, Control and Outcome (PICO) structured questions should be the essential first step.[23] An example of research question for lichen planus (LP) would be “In LP patients of any age, gender, duration of illness having acute or chronic manifestations of disease; localized or generalized other than hypertrophic type with or without associated hypertension and diabetes, would the combination of Mahamanjistadi kashaya, Kaishora Guggulu, Triphala churna, Brihanmarichadi thaila normalize the deranged kapha-vatha dosha and in three month alleviates polymorphous pruritic lesions and associated symptoms as compared to oral and topical steroids?” As in biomedical clinical trials inclusion and exclusion criteria should follow. Trials of traditional medicine require more preparation.[3] Patient selection should match the ayurvedic principles of treatment.[20] According to Ayurveda, analysis of prakruthi and local skin pathology (sthaneeya vikruthi) is mandatory before prescribing. There are locally distinctive doshas (vatha, pitta, and kapha); meaning complex patterns of differing symptoms and signs produce typical “constellations” of clinical signs and symptoms. A table of their comparable biomedical terms is called sthaneeya vikruthi table.[20] Integrative approaches revealed that all allopathic diseases including LP are not described by name in Ayurvedic dermatology. There are only about 18 diseases described in Ayurveda under the chapter kusta (meaning skin diseases).[24] Therefore constructing a vikruthi table of comparable biomedical terms is essential for correct patient selection before prescribing in any disease.[2] It is a table generated by detailing the clinical description of vatha, pitta, and kapha presentations in Ayurveda and its comparable biomedical description.

Integrating ayurveda in the treatment of LP

All patients attending integrative clinic of IAD during the period October 2007 to March 2012 were examined by dermatologists and ayurvedic doctors. There were a total of 98 patients, based on their clinical presentations a Sthaneeya vikruthi table was constructed [Table 1]. This followed the examples of Lymphoedema and Vitiligo.[2]

Table 1.

Sthaneeya vikruthi table of lichen planus comparing ayurvedic description with modern dermatology

We evaluated the safety and efficacy of Ayurvedic treatment for LP in 19 patients using a vikruthi table. All 19 patients based on the features listed in vikruthi table had Vatha-kapha presentation. Following treatment regimen was prescribed for a period of 3 months. (i) Triphala churna[25] (TC): It is a compound powder made up of three medical plants; 7.5 grams per day for above 16 years and 5 grams for children (5-15 years) with lukewarm water at bed time. (ii) Mahamanjistadi decoction (MM):[26] It is an herbalized preparation similar to mixtures made of 46 ingredients. In adults, 15 ml of decoction is diluted with 30 ml of boiled and cooled water with 500 mg tablet of Kaishora guggulu[27] (KG), which contains 8 ingredients, after food twice daily; in children, 10 ml of decoction with one tablet of KG. Brihanmarichadi oil (BM)[28] is made of 32 ingredients, was used for topical application, applied once one and a half hours before bathing. In patients with old lesions of LP, Mahathikthaka decoction[29] with Swayambhuva guggulu[30] and for application Eladi oil[31] was given. Easily digestible food such as vegetables of bitter taste, food prepared with old rice, green gram, wheat, barley, etc., were advised. Over eating especially heavy food, milk and its products such as curd, ghee, and cheese, preparations of jaggery, food prepared of sesame paste and black gram, nonvegetarian items were restricted. Patients were also advised to stop alcohol, smoking, and tobacco chewing. All patients responded to treatment within 3 months. However, postinflammatory pigmentation and dryness of skin remained [Figure 1]. No reoccurrences were noted at a 3 year telephone follow up.

Figure 1.

Changes in lichen planus after 3 months of integrative dermatology treatment

Clinical diagnosis in Ayurveda is based on 11 parameters that are structured using integrative approach. The skin is kept in good health by balance of pitta (comparable to metabolic activities), which determines the color and warmth of skin. But in LP, the kapha (stabilizing force) and vatha (energy) predominance replaces pitta. In order to restore pitta dosha (also called humor), we decided to give treatment, which normalizes three doshas namely vatha, pitta, and kapha (known in Ayurveda as threedosha hara treatment). TC expels vitiated doshas through mild purgation.[25] It also aids absorption of other medicines that are administered simultaneously. MM decoction with KG is effective in skin disease.[27] BM[28] is indicated in skin diseases caused due to kapha dominant features.

There are no previous examples of ID.[2] It took over 4 years of discussion between the different systems of medicine and patient follow up to reach a consensus in treatment. Each doctor closely observed and followed up patients in IAD's ID clinics. Persuading the international community about the practice of ID was done through various international presentations over 6 years.[32] We have not been completely successful persuading our Indian peers about the benefits of integrative treatments. This is particularly important in the context of neglected and common skin diseases in India, and for greater and timely allocation of domestic research grants. However, during the past one decade the IAD has integrated different systems of medicine and demonstrated evidence of its benefits in chronic skin diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Prof Hywel Williams, Cochrane Skin Center, Nottingham who trained them on conducting evidence-based studies in dermatology. This has helped them to convince the Western scientific community, who have already established centers for integrative medicine.

The authors would also like to thank Terence Ryan, Emeritus Professor of Dermatology, Green Templeton College, University of Oxford, for his lead role in mentoring and voicing IAD's experience of ID to their European peers.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine [Internet] US, National Institutes of Health. [Last updated on 2012 Apr 10; cited on 2012 Aug 4]. Available from: http://nccam.nih.gov/

- 2.Narahari SR, Ryan TJ, Bose KS, Prasanna KS, Aggithaya MG. Integrating modern dermatology and Ayurveda in the treatment of vitiligo and lymphedema in India. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:310–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rees L, Weil A. Imbues orthodox medicine with the values of complementary medicine (Editorial) BMJ. 2001;322:119–20. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7279.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nahin RL, Straus SE. Research into complementary and alternative medicine: Problems and potential. BMJ. 2001;322:161–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7279.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chi-keong ON, Ryan TJ. 1st ed. Oxford: International Foundation of Dermatology; 1998. Healthy Skin for All. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burford G, Bodeker G, Ryan TJ. Skin and wound care: Traditional, complementary and alternative medicine in public health dermatology. In: Bodekar G, Burford G, editors. Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Policy and Public Health Perspectives. London: Imperial College Press; 2007. pp. 311–47. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Godlee F. Integrated care is what we want. Editors Choice. Br Med J. 2012;344:e3959. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prospectus [Internet] Government of Kerala: Office of the Commissioner for Entrance Examinations. [Last updated on 2012 Aug 6; cited 2012 Aug 12]. Available from: http://www.cee-kerala.org/docs/keam2012/prospectus/prospectus_keam12.pdf .

- 9.Sheikh K, Nambiar D. Government policies for traditional, complementary and alternative medical services in India: From assimilation to integration? Natl Med J India. 2011;24:245–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.New Delhi: Indian Council for Medical Research; [Last updated on 2012 Aug 6; cited 2012 Aug 12]. Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research on Human Participants [Internet] Available from: http://icmr.nic.in/ethical_guidelines.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mashelkar AR. India's R and D: Reaching for the top. Science. 2005;307:1415–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1110729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramalingaswami V, Satyavati GV. Sir Ram Nath Chopra. Indian J Med Res. 1982;76:5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.New Delhi: Indian Council for Medical Research; [Last updated on 2012 Aug 6; cited 2012 Sep 12]. ICMR centres for advanced research: Annual report 2009–10 [Internet] Available from: http://www.icmr.nic.in/annual/2009-10/english/car.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahanuakar SA, Thatte UM. India: National Book Trust; 2006. Ayurveda Unravelled. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sethi TP, Prasher B, Mukerji M. Ayurgenomics: A new way of threading molecular variability for stratified medicine. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6:875–80. doi: 10.1021/cb2003016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patwardhan B, Joglekar V, Pathak N, Vaidya A. Vaidya-scientists: Catalysing Ayurveda renaissance. Cur Sci. 2011;100:476–83. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pope C, Britten N. The quality of rejection: Barriers to qualitative methods in the medical mind set. BSA medical sociology group annual conference September 1993, York. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Black N. Why we need qualitative research? J Epidemiol Community Health. 1994;48:425–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.48.5.425-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. General Guidelines for Methodologies on Research and Evaluation of Traditional Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Narahari SR, Ryan TJ, Aggithaya MG, Bose KS, Prasanna KS. Evidence based approaches for Ayurvedic traditional herbal formulations: Toward an Ayurvedic CONSORT model. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14:769–76. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narahari SR, Aggithaya MG, Suraj KR. Conducting Literature Searches on Ayurveda in PubMed, Indian and other databases. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:1225–37. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams H. How to critically appraise a study reporting effectiveness of an intervention. In: Williams H, Bigby M, Diepgen T, Herxheimer A, Naldi L, Rzany B, et al., editors. Evidence-Based Dermatology. London: British Medical Journal Books; 2003. pp. 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narahari SR, Aggithaya MG, Suraj KR. A protocol for systematic reviews of Ayurveda treatments. Int J Ayurveda Res. 2010;1:192–205. doi: 10.4103/0974-7788.76791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madhava . Kusta Nidana. Varanasi: Chowkhamba Orientalia; 2001. Madhava Nidana. Verses. 25-30. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarngadhara . Madhyamakhanda Churna Kalpana. Varanasi: Krishnadas Academy; 2000. Sarngadhara Samhita. Verses. 9-11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaidyan KV, Pillai SG. Kashayayogangal. In: Vaidyan KV, Pillai SG, editors. Sahasrayogam with Sujanapriya Commentary. Alappuzha: Vidyarambam Publishers; 2007. p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaidyan KV, Pillai SG. Vatakadiyogangal. In: Vaidyan KV, Pillai SG, editors. Sahasrayogam with Sujanapriya Commentary. Alappuzha: Vidyarambam Publishers; 2007. p. 157. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cakrapani Datta. Cakradatta Kusta Chikitsitam. Delhi: Chowkhamba Orientalia; 2007. Verses. 138-45. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vagbhata . Kusta chikitsitham. Varanasi: Krishnadas Academy; 2000. Astanga Hrudaya. Verses. 8-11. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shodhala . Varnasi, India: Chowkhamba Sanskrit Sansthan; 2005. Gadanigraha-Prayogakhanda-gutikadhikara; pp. 365–71. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaidyan KV, Pillai SG. Thailayogangal. In: Vaidyan KV, Pillai SG, editors. Sahasrayogam with Sujanapriya Commentary. Alappuzha: Vidyarambam Publishers; 2007. p. 275. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Narahari SR. More than one system of medicine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;2:17. [Google Scholar]