Abstract

Disabling pansclerotic morphea (DPM) of childhood is a rare generalized type of localized scleroderma (LS) that is known to follow an aggressive course with pansclerotic lesions leading to severe joint contractures and consequent immobility. Mortality is due to complications of the disease such as bronchopneumonia, sepsis, or gangrene. There is no specific laboratory finding. Treatment protocols are still evolving for this severe recalcitrant disorder. Extracutaneous manifestations are rarely reported in DPM. We present the case of a 7-year-old girl with DPM with severe extracutaneous manifestations in the form of gastrointestinal and vascular disease, whose disease progressed rapidly. In spite of treatment with methotrexate, corticosteroids, and PUVA therapy, she ultimately succumbed to her illness due to sepsis.

Keywords: Disabling pansclerotic morphea of childhood, extracutaneous manifestations, gangrene, juvenile localized scleroderma

Introduction

What was known?

Disabling pansclerotic morphea (DPM) of childhood is a generalized type of juvenile localized scleroderma (JLS) leading to severe involvement of all skin layers, even extending to the underlying muscles and bones in few cases. Mortality is uncommon and is due to bronchopneumonia, sepsis, or gangrene. Extracutaneous manifestations are unusual in JLS due to its primarily skin directed pathology. Traditionally, JLS is differentiated from systemic sclerosis by its lack of systemic involvement.

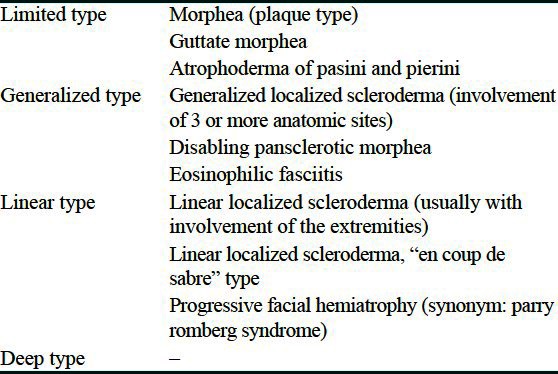

Two different forms of scleroderma are progressive systemic scleroderma with systemic sclerosis of soft tissues and other organs, without localized plaque formation in the skin and localized scleroderma (LS) with localized plaque formation and without involvement of visceral organs. Juvenile LS (JLS) can be further classified depending on amount, the extent of involvement, and the depth of the fibrosis [Table 1].[1] Disabling pansclerotic morphea (DPM) of childhood causes deep cutaneous sclerosis extending into muscle, fascia, and occasionally underlying bone and can severely affect the quality of life, even being fatal.[2]

Table 1.

Classification of localized scleroderma

Case Report

A 7-year-old female child was brought with complaints of tightness of skin since the past 1 year, starting on the lower limbs and gradually progressing to involve the whole body. Joint contractures resulting in severe disability were present since 5 months. She had no history of trauma or vaccination. There was no personal or family history of autoimmune disease, Raynaud's phenomenon, difficulty in swallowing, or retrosternal burning pain. On examination, there was generalized sclerosis of the skin involving the extremities, trunk, and face. Dyspigmented sclerotic plaques, few of them crusted, were seen all over the body. Her limbs were fixed by contractures to an extent that she could not walk [Figures 1 and 2]. Chest expansion was reduced due to chest wall sclerosis. There was bilateral lagophthalmos and ectropion. Scars of previous healed ulcerations were seen on legs. Investigations showed hemoglobin of 7.1 g/dl and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 53 mm in the first hour. Anti-nuclear antibody was positive (1:80, speckled pattern), anti-dsDNA and anti Scl-70 antibodies were negative. Chest radiograph and high resolution computed tomography-thorax were normal. Barium swallow showed evidence of gastroesophageal reflux. Pulmonary function test was not possible as patient was unable to blow. Radiographs of the limb bones were normal. Histopathology showed a sclerotic dermis with tightly packed collagen fibers, sclerosis involving the deeper layers of subcutaneous tissue and fascia with marked reduction of skin adnexae and a small amount of lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate. Patient was started on tablet methotrexate 7.5 mg/week. However, after 3 months, as there was no improvement, inj. methylprednisolone 15 mg/kg intravenously as a pulse for 3 consecutive days was added. The condition of the patient continued to deteriorate with increasing sclerosis, most evident in periorbital area [Figure 3], development of recalcitrant cutaneous ulcers, and cicatricial alopecia over scalp. Meanwhile, she started developing cyanotic discoloration of the digits of the right foot [Figure 4]. On evaluation, patient was found to have thrombosis of right dorsalis pedis artery. A normal 2D echocardiography ruled out a cardiac source. Heparin followed by oral warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel failed in preventing gangrene and autoamputation of the 2nd right toe. At this time, PUVA with 8-methoxypsoralen was started. However, she could take only 2 sittings before succumbing due to septicemia.

Figure 1.

Generalized sclerosis of the skin with joint contractures and crusted erosions on knee

Figure 2.

Sclerosis and contractures of hands and feet

Figure 3.

Before and after 3 months of methotrexate showing worsening sclerosis with increasing ectropion and lagophthalmos

Figure 4.

Cyanosis over toes, which later turned into gangrene

Discussion

JLS, an autoimmune disease associated with induration of the skin, is usually confined to the skin and subcutaneous tissue and is thought to be self-limiting. However, underlying structures like muscle, fascia, and bone can be involved in almost one-quarter of JLS, especially in linear and deep forms.[3] A large study with 750 children showed that at 65%, the linear type is the most common, followed by the plaque type with 26%, the generalized type with 7%, and the deep type with 2%, respectively.[4] DPM, a subtype of generalized morphea, was first described in 1923 and later in detail by Diaz-Perez et al. in 1980.[2] The initial areas of involvement are the extremities, later spreading to the trunk, face, and scalp, although the acral areas are usually spared,[2] though they were involved in our case [Figure 2]. Considering pansclerosis, younger age of onset, rapidly progressive course with absence of Raynaud's phenomenon, and features of systemic scleroderma, a diagnosis of DPM was made. JLS with extracutaneous manifestations is a newly-described subset of the disease. In the study on JLS by Zulian et al., at least one extracutaneous involvement was present in 22% of patients while 4% had multiple manifestations. The commonest was articular (47.2%) followed by neurologic (4.4%), vascular (2.4%), ocular (2.1%), gastrointestinal (1.6%), respiratory (0.7%), cardiac (0.3%), and renal (0.003%). Other autoimmune conditions were present in 1.7% of patients. Systemic scleroderma developed in one case.[3] Our patient had gastrointestinal and vascular involvement. Anti-cardiolipin antibodies (aCL) have been found in 25% of patients with generalized variant of JLS.[4] Further, an increase in the PTTK (partial thromboplastin time with kaolin) values have been documented in all the childhood-onset scleroderma patients, which may indicate an abnormal coagulopathy as a result of early endothelial cell damage/activation or tissue factor activation.[5] As the patient rapidly deteriorated and succumbed to her illness after her vascular involvement, aCL and PTTK values could not be tested. Our patient's arterial thrombosis could have been related to either of these factors. Vascular involvement in JLS has also been reported in the form of Raynaud's phenomenon (0.02%), vasculitis, and deep venous thrombosis.[2] Gastroesophageal reflux disease is the only reported gastrointestinal manifestation, which was also seen in our case.[2] Recalcitrant ulcers, prone to secondary carcinomatous changes, are commonly observed in DPM. There are no characteristic serological parameters in JLS in contrast to systemic scleroderma. In generalized types of JLS, especially during active stages, anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-histone antibodies, hypergammaglobulinemia, and eosinophilia might be present. ANA occurs in 31% of patients.[3] Although the exact pathogenesis of this disease is unknown, increased collagen synthesis and deposition, vascular damage and altered immunoregulation may be causative.[6] The prognosis for patients is poor. Numerous treatments have been tried with limited benefit, such as penicillamine, anti-malarial drugs, retinoids, calcipotriol, imiquimod, ciclosporin, and interferon gamma. As methotrexate has been the most frequently used drug in the treatment of widespread morphea in children,[4] it was started as an initial treatment. Corticosteroids and low-dose methotrexate have also been reported to be beneficial in few studies,[3,7] and hence methylprednisolone pulse therapy was added when methotrexate alone did not work. The mechanism of action of low-dose methotrexate in improving skin fibrosis may be through direct action on the skin fibroblasts or due to its anti-inflammatory effect.[8] Many studies have reported the successful use of PUVA and UVA1 in treating DPM.[6,9] UVA irradiation has been shown to reduce procollagen synthesis and induce the expression of collagenase-1, an enzyme, that cleaves collagen bundles.[10]

What is new?

JLS, even though classically an exclusive cutaneous disease, nevertheless can cause systemic involvement. DPM is a severe variant of JLS and can cause significant morbidity and in few cases, even mortality. Extracutaneous manifestations are unusual in DPM. Our case had 2 extracutaneous manifestations in the form of acral gangrene and gastrointestinal involvement. The gangrenous changes lead to sepsis and thus worsened the prognosis in our patient, ultimately leading to her demise. This case illustrates the need for a high index of suspicion for extracutaneous manifestations in patients of JLS, especially the severe generalized variants like DPM.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Kreuter A, Krieg T, Worm M, Wenzel J, Gambichler T, Kuhn A, et al. Diagnosis and therapy of circumscribed scleroderma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7(Suppl 6):S1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2009.07178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diaz-Perez JL, Connolly SM, Winkelmann RK. Disabling pansclerotic morphea of children. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:169–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zulian F, Vallongo C, Woo P, Russo R, Ruperto N, Harper J, et al. Localized scleroderma in childhood is not just a skin disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2873–81. doi: 10.1002/art.21264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zulian F, Athreya BH, Laxer R, Nelson Am, Feitosa de Oliviera SK, Punaro MG, et al. Juvenile Scleroderma Working Group of the Pediatric Rheumatology European Society (PRES). Juvenile localized scleroderma: Clinical and epidemiological features in 750 children. An international study. Rheumatology. 2006;45:614–20. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vancheeswaran R, Black CM, David J, Hasson N, Harper J, Atherton D, et al. Childhood onset scleroderma: Is it different from adult-onset disease. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1041–9. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gruss C, Stucker M, Kobyletzki G, Schreiber D, Altmeyer P, Kerscher M, et al. Low dose UVA1 phototherapy in disabling pansclerotic morphoea of childhood. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:293–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb14925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreuter A, Gambichler T, Breuckmann F, Rotterdam S, Freitag M, Stuecker M, et al. Pulsed high-dose corticosteroids combined with low-dose methotrexate in severe localized scleroderma. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:847–52. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.7.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van den Hoogen FH, van den Kraan PM, Boerbooms AM, van den Berg WB, van Lier HJ, van de Putte LB, et al. Effects of methotrexate on glycosaminoglycan production by scleroderma fibroblasts in culture. Ann Rheum Dis. 1993;52:758–76. doi: 10.1136/ard.52.10.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scharffetter-Kochanek K, Goldermann R, Lehmann P, Holzle E, Goerz G. PUVA therapy in disabling pansclerotic morphoea of children. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:830–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sunderkötter C, Kuhn A, Hunzelmann N, Beissert S. Phototherapy: A promising treatment option for skin sclerosis in scleroderma? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45(Suppl 3:iii):52–4. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]