Abstract

We conducted a study on interstellar formamide, NH2CHO, toward star-forming regions of dense molecular clouds, using the telescopes of the Arizona Radio Observatory (ARO). The Kitt Peak 12 m antenna and the Submillimeter Telescope (SMT) were used to measure multiple rotational transitions of this molecule between 100 and 250 GHz. Four new sources of formamide were found [W51M, M17 SW, G34.3, and DR21(OH)], and complementary data were obtained toward Orion-KL, W3(OH), and NGC 7538. From these observations, column densities for formamide were determined to be in the range of 1.1×1012 to 9.1×1013 cm−2, with rotational temperatures of 70–177 K. The molecule is thus present in warm gas, with abundances relative to H2 of 1×10−11 to 1×10−10. It appears to be a common constituent of star-forming regions that foster planetary systems within the galactic habitable zone, with abundances comparable to that found in comet Hale-Bopp. Formamide's presence in comets and molecular clouds suggests that the compound could have been brought to Earth by exogenous delivery, perhaps with an infall flux as high as ∼0.1 mol/km2/yr or 0.18 mmol/m2 in a single impact. Formamide has recently been proposed as a single-carbon, prebiotic source of nucleobases and nucleic acids. This study suggests that a sufficient amount of NH2CHO could have been available for such chemistry. Key Words: Formamide—Astrobiology—Radioastronomy—ISM—Comets—Meteorites. Astrobiology 13, 439–453.

1. Introduction

A current theory in the paradigm of the RNA world is that nucleobases originated from the condensation of HCN in the presence of water (Orgel, 2004). A tetramer arises from the polymerization, which then leads to adenine, guanine, and other products. However, there appear to be some issues in ascribing to HCN the role of “absolute protagonist” in the prebiotic chemistry of nucleic acids (e.g., Saladino et al., 2006). One issue is the thermodynamic instability of HCN polymers under hydrolytic conditions. At low concentrations (<0.01 M), the hydrolysis of HCN to NH2CHO prevails over its polymerization (Sanchez et al., 1967). Higher concentrations needed to promote the polymerization route are hard to realize for HCN under early Earth temperature and pressure conditions, especially because it is more volatile than water and cannot simply be concentrated by evaporation. The competition between HCN polymerization and hydrolysis to formamide consequently favors the latter process (e.g., Costanzo et al., 2007). Furthermore, HCN condensation, unless in very specific conditions like eutectic freezing (Cleaves et al., 2006), or with unrealistic prebiotic concentrations of reagents (Shapiro, 2002), only produces purines, not pyrimidines, in relevant yields. HCN therefore does not appear to have the multifunctional reactivity required to lead to the necessary nucleobases upon which life is built.

Recently, formamide, NH2CHO, has been proposed as either an alternative to HCN in the prebiotic scheme (Costanzo et al., 2007) or a possible nonvolatile source of HCN (Barks et al., 2010), leading mainly to the synthesis of purines. Formamide has properties that overcome the difficulties arising in HCN. Upon heating at 110–160°C in the presence of metal oxides and mineral catalysts, neat formamide will condense into both purines and pyrimidines (Costanzo et al., 2007). It has also been shown that purines can form from formamide at lower temperatures upon UV irradiation, with or without the presence of calcium carbonate or sodium pyrophosphate (Barks et al., 2010). Moreover, unlike volatile HCN, formamide has a boiling point of 210°C and thus can be easily concentrated and accumulated by simple evaporation in a “drying lagoon” hypothesis, making the concentration threshold less of an issue. The reactivity of NH2CHO goes beyond nucleobase synthesis as well; Costanzo et al. (2007) found that phosphorylation of nucleosides to produce nucleotides, the building blocks of nucleic acids, readily occurs in the presence of formamide and a phosphate donor. Finally, formamide in one molecule contains the four most important elements for biological systems: H, N, C, and O.

Based on these properties, a scenario for a prebiotic formamide-based synthesis of informational polymers has been proposed (Saladino et al., 2006). In the presence of formamide, nucleobases would form in the crevices of a mineral catalyst based in clay with a phosphate surface in dry, moderately hot conditions. The bases would be washed into aqueous solution, and if TiO2 is present, sugar chains would start to attach to them. If these simple polymers survive and phosphorylation occurs, they could lead to RNA strands.

While formamide appears to meet prebiotic requirements of stability and reactivity, another important criterion is availability and abundance as a starting material. Formamide can be created from the hydrolysis of dilute HCN in water, as mentioned. The quantity of formamide produced via this route is not known. Formamide could also be naturally available, delivered exogenously to Earth via comets, interplanetary dust particles (IDPs), and meteorites (e.g., Costanzo et al., 2007). Formamide has been observed in comet Hale-Bopp via the gas-phase detection of three rotational transitions, with abundance relative to water of 0.01% (Bockelee-Morvan et al., 2000). Alkyl amides, such as acetamide and propionamide, have also been identified in carbonaceous chondrites (Cooper and Cronin, 1995). Exogenous delivery would require extraterrestrial synthesis, perhaps in molecular clouds.

Following the initial detection of formamide in the interstellar medium in the dense cloud SgrB2 by Rubin and coworkers (1971), studies of interstellar formamide have been sporadic, mostly in the context of spectral surveys. Multiple transitions of formamide have been identified in surveys of SgrB2(OH), SgrB2(N) (Cummins et al., 1986; Turner, 1991; Nummelin et al., 2000; Halfen et al., 2011), and Orion-KL (Blake et al., 1986; Turner, 1991). In addition, as part of a survey of organic species in young stellar objects, NH2CHO was also found in six other molecular clouds, including NGC 7538 and W3(H2O) (Bisschop et al., 2007). Beam-corrected column densities of the molecule were typically found to be in the range of 1013 to 1015 cm−2, with abundances relative to H2 of ∼ 10−11 to 10−9.

To further investigate the availability and distribution of formamide in our galaxy, we have conducted additional observations of this molecule toward star-forming clouds, using the telescopes of the Arizona Radio Observatory (ARO). Four new sources of NH2CHO were found, and new transitions were measured in three additional sources. From these measurements, abundances of formamide were determined, which were then compared to that in comets. Here, these results are presented, as well as an estimate of the amount of extraterrestrial formamide that could have been released to Earth by comets, meteorites, and IDPs.

2. Quantum Mechanics of Formamide

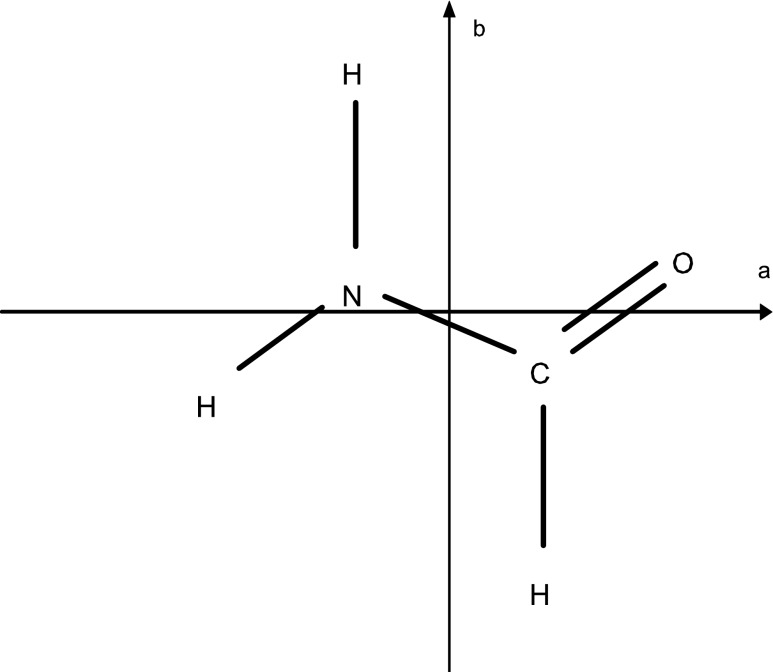

The well-characterized rotational spectrum of formamide has been the subject of numerous studies (Blanco et al., 2006; Kryvda et al., 2009). Formamide is a near prolate asymmetric top molecule with a nearly flat structure, as shown in Fig. 1. The molecule has a strong a-dipole moment component of 3.62 D and a smaller b-dipole moment of 0.85 D. Therefore, both a- and b-dipole-allowed transitions occur in this species, with the respective selection rules ΔJ=0,±1, ΔKa=0, ΔKc=±1 and ΔJ=0,±1, ΔKa=±1, ΔKc=±1. Here, J is the quantum number describing the overall rotational energy of the molecule, while Ka and Kc represent the projection of the rotational angular momentum along two principal axes. The nuclear spin of the nitrogen atom (I=1) also gives rise to a quadrupole hyperfine structure, although at millimeter wavelengths such splittings are generally not resolved. Formamide thus has a complex rotational spectrum. The rotational transitions observed in this work were chosen on the basis of their intensities, obtained from the CDMS catalogue (http://www.astro.uni-koeln.de/cdms) and were also checked for potential contamination from lines of other molecules.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of formamide. NH2CHO is a nearly flat prolate asymmetric top. The principal moments of inertia a and b are indicated.

3. Observations

The measurements were conducted at the facilities of the ARO: the 12 m telescope at Kitt Peak and the Submillimeter Telescope (SMT) on Mt. Graham, both in Arizona. The observations were carried out during a series of runs from May 2005 to June 2012. Sources and telescope parameters are listed in Tables 1 and 2. The 12 m telescope was employed for the 3 and 2 mm observations, while those at 1 mm were conducted with the SMT. The receivers used at 2 and 3 mm employed SIS mixers, operated in single-sideband mode with typical image rejection of ≥16 dB, achieved by tuning the mixers. For measurements made after 2008 May, a new receiver with ALMA-type Band 3 sideband-separating mixers was used. Image rejection in this case was typically ≥15 dB. The backends used were 256 channel filter banks with 500 or 1000 kHz resolution, configured in parallel mode (2×128) to accommodate the two perpendicular polarizations. The temperature scale at the 12 m is given in terms of  . The main beam brightness temperature is then defined as

. The main beam brightness temperature is then defined as  , where ηc is the beam efficiency corrected for forward spillover losses. In the 1 mm band at the SMT, a dual-channel receiver utilizing ALMA-type Band 6 sideband-separating mixers was used, with image rejection ≥15 dB. The backend used was a 2048 channel filter bank with 1 MHz resolution, configured in parallel mode (2×1024 channels) for the two receiver channels. The temperature scale at the SMT is defined in terms of

, where ηc is the beam efficiency corrected for forward spillover losses. In the 1 mm band at the SMT, a dual-channel receiver utilizing ALMA-type Band 6 sideband-separating mixers was used, with image rejection ≥15 dB. The backend used was a 2048 channel filter bank with 1 MHz resolution, configured in parallel mode (2×1024 channels) for the two receiver channels. The temperature scale at the SMT is defined in terms of  , where

, where  , and ηB is the main beam efficiency. Data were taken in position-switching mode with the off position 30 arcmin west in azimuth. Pointing was checked every 1.5 h on nearby continuum sources, usually a planet. Local oscillator shifts were done for each line to protect against possible image contamination.

, and ηB is the main beam efficiency. Data were taken in position-switching mode with the off position 30 arcmin west in azimuth. Pointing was checked every 1.5 h on nearby continuum sources, usually a planet. Local oscillator shifts were done for each line to protect against possible image contamination.

Table 1.

Molecular Clouds in Observational Sample

| Source | α (B1950.0) | δ (B1950.0) | DGC(kpc) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orion-KL | 05h32m46.8s | −05°24′23″ | 8.3 |

| W51M | 19h21m26.2s | 14°24′43″ | 6.1 |

| G34.3 | 18h50m46.4s | 01°11′14″ | 5.1 |

| NGC 7538 | 23h11m36.6s | 61°11′47″ | 8.9 |

| W3(OH) | 02h23m17.0s | 61°38′54″ | 9.6 |

| DR21(OH) | 20h37m14.0s | 42°12′00″ | 8.0 |

| M17 SW | 18h17m31.0s | -16°13′00″ | 6.1 |

Table 2.

Observed Transitions of NH2CHO

| Frequency | Transition | ΔElower(cm−1) | Beam efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 84542.5 | 40,4 → 30,3 | 4.24 | 0.93 |

| 87849.0 | 41,3 → 31,2 | 6.47 | 0.92 |

| 102064.5 | 51,5 → 41,4 | 8.89 | 0.90 |

| 105464.4 | 50,5 → 40,4 | 7.06 | 0.90 |

| 106108.3 | 54,2 → 44,1 54,1 → 44,0 |

40.21 | 0.89 |

| 106134.7 | 53,3 → 43,2 | 25.72 | 0.89 |

| 106141.7 | 53,2 → 43,1 | 25.72 | 0.89 |

| 106541.9 | 52,3 → 42,2 | 15.37 | 0.89 |

| 109753.7 | 51,4 → 41,3 | 9.40 | 0.89 |

| 131618.2 | 61,5 → 51,4 | 13.06 | 0.84 |

| 142701.7 | 71,7 → 61,6 | 16.37 | 0.82 |

| 146871.8 | 70,7 → 60,6 | 14.79 | 0.81 |

| 148223.5 | 72,6 → 62,5 | 23.14 | 0.80 |

| 148556.7 | 76,1 → 66,0 76,2 → 66,1 |

89.39 | 0.80 |

| 148567.5 | 75,3 → 65,2 75,2 → 65,1 |

66.63 | 0.80 |

| 148599.9 | 74,4 → 64,3 74,3 → 64,2 |

48.00 | 0.80 |

| 148667.8 | 73,5 → 63,4 | 33.51 | 0.80 |

| 148709.5 | 73,4 → 63,3 | 33.51 | 0.80 |

| 153432.5 | 71,6 → 61,5 | 17.45 | 0.79 |

| 167321.1 | 80,8 → 70,7 | 19.69 | 0.76 |

| 227606.4 | 110,11 → 100,10 | 38.35 | 0.75 |

| 247391.6 | 120,12 → 110,11 | 46.05 | 0.75 |

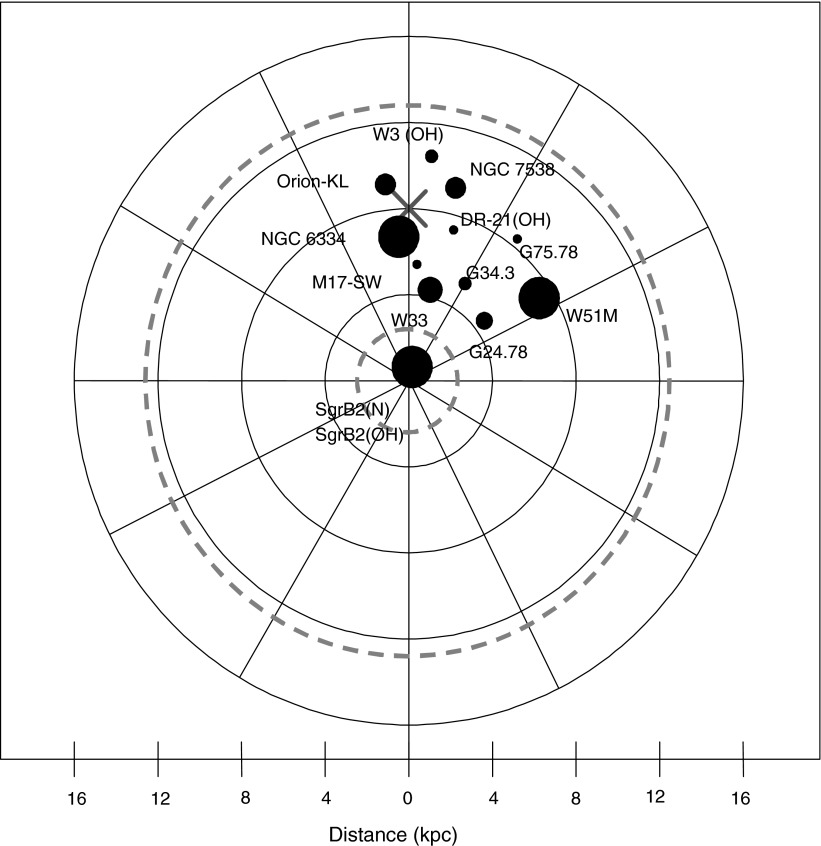

The celestial coordinates of all sources are provided in Table 1, as well as the distances of the objects from the Galactic Center, DGC (in kiloparsecs). Figure 2 shows the location of the clouds in the Galaxy and with respect to the galactic habitable zone, which will be discussed later. Table 2 summarizes the transitions of NH2CHO studied in this work.

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of the Milky Way Galaxy. The Sun is indicated by the cross. The galactic habitable zone is indicated by the dashed, gray circles, based on work of Gowanlock et al. (2011). The approximate galactic positions of the molecular clouds where formamide has been detected are indicated by filled circles. The circle size indicates the relative amount of formamide. The figure summarizes the current work and past observations (e.g., Cummins et al., 1986; Bisschop et al., 2007; Halfen et al., 2011). The distances are in kiloparsecs, or kpc (1 kpc ∼ 3259 light-years).

4. Results

Four new sources of formamide were found: W51M, G34.3, DR21(OH), and M17 SW. Additional lines were observed in Orion-KL, W3(OH), and NGC 7538. Note that one line of NH2CHO was also tentatively detected in G34.26+0.15 (Mookerjea et al., 2007). All sources are sites of massive star formation and harbor compact hot core regions. Hot cores are warm (70–300 K), dense [n(H2)>106 cm−3] clumps of gas and dust near star-forming sites. The hot core phase lasts approximately 105 to 106 years (e.g., Garrod and Herbst, 2006) and appears to be the most chemically rich in the interstellar medium. They are also where the collapsing gas and dust are giving rise to new stars, planetesimals, and possibly planets.

A summary of the spectral lines of formamide observed toward the seven molecular clouds is given in Table 3. All are a-type transitions and arise from levels <130 K above ground state. The table lists the line intensities  (or

(or  ), the linewidths at half-maximum ΔV1/2, and the velocities with respect to the local standard of rest (LSR), VLSR, for all observed features. The NH2CHO lines appear to exhibit typical linewidths and LSR velocities of the given molecular clouds.

), the linewidths at half-maximum ΔV1/2, and the velocities with respect to the local standard of rest (LSR), VLSR, for all observed features. The NH2CHO lines appear to exhibit typical linewidths and LSR velocities of the given molecular clouds.

Table 3.

Observations of NH2CHO

|

Transition |

Orion-KL |

W51M |

G34.3 |

NGC 7538 |

M17 SW |

W3(OH) |

DR21(OH) |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J″Ka,Kc → |

|

VLSR |

ΔV1/2 |

|

VLSR |

ΔV1/2 |

|

VLSR |

ΔV1/2 |

|

VLSR |

ΔV1/2 |

|

VLSR |

ΔV1/2 |

|

VLSR |

ΔV1/2 |

|

VLSR |

ΔV1/2 |

| J′Ka,Kc | (mK) | (km/s) | (km/s) | (mK) | (km/s) | (km/s) | (mK) | (km/s) | (km/s) | (mK) | (km/s) | (km/s) | (mK) | (km/s) | (km/s) | (mK) | (km/s) | (km/s) | (mK) | (km/s) | (km/s) |

| 41,3 → 31,2 | 27 | 7 | 5.1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 51,5 → 41,4 | 60 | 7 | 6.8 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 50,5 → 40,4 | 80 | 7 | 4.3 | 77 | 56 | 9.2 | 38 | 57 | 5.6 | 8.7 | −59 | 5.1 | 8.2 | 18 | 8.5 | 11.1 | −4 | 5.0 | |||

| 54,2 → 44,1 | 17 | 9 | 4.2 | 82 | 58 | 11.2 | 16 | 58 | 8.4 | ||||||||||||

| 53,3 → 43,2 | 22 | 7 | 4.3 | 80 | 57 | 8.4 | 33 | 60 | 7.0 | ||||||||||||

| 53,2 → 43,1 | 95 | 61 | 12.8 | 25 | 57 | 8.4 | |||||||||||||||

| 52,3 → 42,2 | 45 | 8 | 5.7 | 55 | 56 | 12.6 | |||||||||||||||

| 51,4 → 41,3 | 95 | 56 | 9.6 | 45 | 57 | 6.8 | |||||||||||||||

| 61,5 → 51,4 | 122 | 9 | 5.7 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 71,7 → 61,6 | 150 | 7 | 4.8 | 110 | 58 | 9.5 | 73 | 56 | 6.3 | 10.7 | −60 | 4.6 | 7.7 | −47 | 5.0 | 9.7 | −3 | 4.2 | |||

| 70,7 → 60,6 | 724 | 6 | 5.1 | 180 | 57 | 11.2 | 70 | 59 | 8.0 | 7.4 | −60 | 4.9 | 6.4 | 17 | 10.2 | 20.5 | −48 | 5.1 | 18.8 | −4 | 4.1 |

| 72,6 → 62,5 | 94 | 6 | 5.5 | 110 | 58 | 11.5 | |||||||||||||||

| 76,1 → 66,0 | 80 | 9 | 4.0 | 47 | 58 | 8.1 | |||||||||||||||

| 75,3 → 65,2 | 60 | 5 | 4.0 | 74 | 56 | 10.1 | |||||||||||||||

| 74,4 → 64,3 | 110 | 7 | 6.0 | 103 | 59 | 9.1 | 46 | 60 | 4.9 | ||||||||||||

| 73,5 → 63,4 | 100 | 9 | 5.0 | 100 | 60 | 10.1 | 7.4 | −59 | 4.9 | 5.8 | 23 | 10.1 | 10.5 | −44 | 5.0 | ||||||

| 73,4 → 63,3 | 54 | 8 | 6.0 | 93 | 59 | 11.1 | 50 | 58 | 6.3 | ||||||||||||

| 71,6 → 61,5 | 120 | 7 | 5.8 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 80,8 → 70,7 | 140 | 7 | 5.4 | ||||||||||||||||||

110,11 →

|

270 | 8 | 5.3 | ||||||||||||||||||

120,12 →

|

350 | 7 | 5.3 | ||||||||||||||||||

Measured as  (K).

(K).

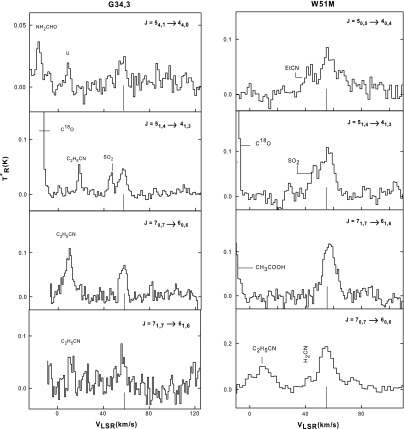

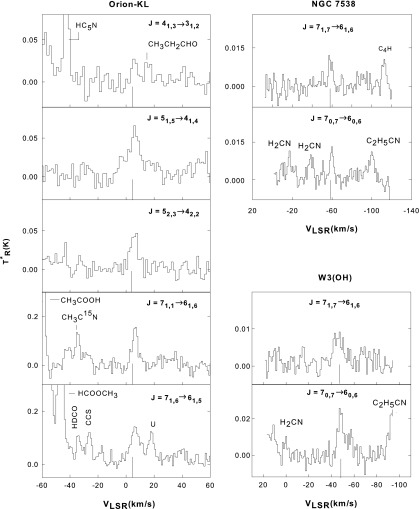

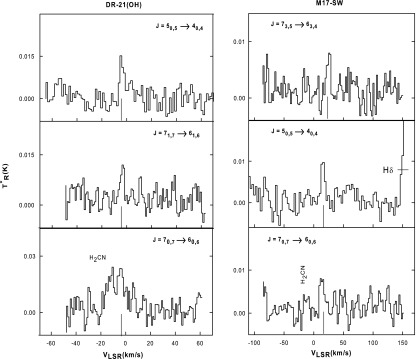

Representative spectra of formamide transitions measured toward each cloud are displayed in Figs. 3–5. The quantum numbers of the transition detected are given above each spectrum, and the actual formamide features are indicated by a line at the average LSR velocity for each cloud. Spectral lines arising from other complex organic molecules characteristic of hot cores, like C2H5CN and CH3COOH, are also visible in these data. Figure 3 displays representative lines measured toward the new sources G34.3 and W51M, while Fig. 4 shows those in DR21(OH) and M17 SW. Figure 5 presents data measured toward Orion-KL, NGC 7538, and W3(OH).

FIG. 3.

Example spectra of formamide transitions observed toward G34.3 (left panels) and W51M (right panels) at 3 and 2 mm in wavelength with the ARO 12 m telescope. The spectral resolution is 500 kHz for all data, except the J=70,7→60,6 transition in W51M, where it is 1 MHz. The quantum numbers for each transition are shown on each panel. The vertical line under each spectrum indicates the average cloud LSR velocity, near 58 km/s for both regions. Other organic molecules can be seen in the data, such as C2H5CN and HCOOCH3.

FIG. 5.

Example spectra of formamide transitions observed toward Orion-KL (left panels), NGC 7538, and W3(OH) (right panels) at 3 and 2 mm with the ARO 12 m telescope. The spectral resolution is 500 kHz. The quantum numbers for each transition are shown on each panel. The vertical line under the data indicates the cloud average LSR velocity: 8 km/s for Orion-KL, −58 km/s for NGC 7538, and −48 km/s for W3(OH). Other molecular features are present in these spectra.

FIG. 4.

Example spectra of formamide transitions observed toward DR21(OH) (left panels) and M17 SW (right panels) at 3 and 2 mm with the ARO 12 m telescope. The spectral resolution is 500 kHz. The quantum numbers for each transition are shown on each panel. The vertical line under each spectrum indicates the cloud average LSR velocity: −3 km/s for DR21(OH) and 18 km/s for M17 SW.

The W51 molecular cloud complex, located 7 kpc from the Sun, comprises several hot core regions, including W51M (Genzel et al., 1982). For W51M, 14 transitions were observed, with intensities from 0.047 to 0.18 K. The LSR velocities are typically VLSR=56–58 km/s, canonical values for this source, and the linewidths fall in the range of 8–12 km/s, also typical (e.g., Bell et al., 1993). This cloud is a new source for NH2CHO.

Toward G34.3, nine transitions of NH2CHO were detected. This cloud, at a distance of 4 kpc, contains a cometary-shaped ultracompact HII region and an isolated hot molecular core. The core region is known to be associated with numerous organic molecules, such as CH3OH and CH3CCH (Macdonald et al., 1996; Kim et al., 2000). Toward G34.3, line intensities of formamide range from 0.016 to 0.073 K; the linewidths are typically 5–8 km/s, with LSR velocities of 56–60 km/s, as also found for larger species such as CH3OH, HCOOCH3, and CH3OCH3 by Mookerjea et al. (2007).

The M17 region is a prominent HII region–molecular cloud complex, located about 2.2 kpc from Earth, and is considered to be a prime example of triggered star formation (Wilson et al., 2003). M17 SW is thought to contain young stellar objects and a photon-dominated region (PDR). Formamide appears to be associated with the general molecular cloud, rather than the PDR, judging from the measured linewidth near 10 km/s. Molecules associated with the PDR itself, such as HOC+, exhibit narrower lines, although they all have velocities near 20 km/s, as found for NH2CHO (Apponi et al., 1999). Larger molecules such as formamide may be less abundant in PDRs because the stronger UV field pervasive in those regions leads to their photodissociation (Apponi et al., 1999).

DR21(OH) is a well-known high-mass star-forming region, with bright OH maser emission (e.g., Zapata et al., 2012). The source contains several dense clumps. The formamide line parameters (VLSR=−4 km/s and ΔV1/2=4–5 km/s) are typical for species such as CS and CH3OH (Chandler et al., 1993). High-velocity wings seen at certain positions near DR21(OH) are not apparently present in formamide.

Toward Orion-KL, 19 transitions were observed, with intensities ranging from 0.017 to 0.724 K (see Table 3 and Fig. 5). Orion-KL is an IR source contained in the giant Orion Molecular Cloud 1, located only at a distance of 450 pc. It is chemically rich, as attested by various spectral line surveys in the 3, 2, 1, and 0.8 mm bands (e.g., Johansson et al., 1984; Turner, 1991; Ziurys and McGonagle, 1993; Sutton et al., 1995). The linewidths of the NH2CHO features are typically between 4 and 6 km/s, while the LSR velocities are between 6 and 9 km/s. The warm gas core of the Orion A region consists of at least three distinct regions: the hot core, the plateau, and the compact ridge, with LSR velocities of 5, 8, and 7.5 km/s, and typical linewidths of ΔV1/2 ∼10, 20–30, and 4–6 km/s, respectively (e.g., Sutton et al., 1995; Lerate et al., 2008). These regions are surrounded by a cooler quiescent extended ridge, with ΔV1/2 ∼3 km/s and LSR velocity of 10 km/s. Our results indicate that formamide emission comes mainly from the compact/extended ridge region.

NGC 7538 is an HII, star-forming region at a 2.7 kpc distance from Earth, which harbors three main activity centers containing massive stellar objects at different evolutionary stages (e.g., Wright et al., 2012). These observations focused on the gas associated with the massive young star IRS 1, which drives a molecular outflow (De Buizer and Minier, 2005). Four transitions of formamide were measured in NGC 7538, all of which had weak intensities (∼10 mK) and exhibited linewidths of ∼5 km/s at a velocity of −59 to −60 km/s. Similar line parameters have been measured in CS in this source (Kameya et al., 1986); they suggest that formamide does not participate in the molecular outflow centered on IRS 1. The molecule had been previously detected in NGC 7538 by Bisschop et al. (2007).

W3(OH) is a compact HII region 2 kpc distant, situated in the massive W3 cloud complex (Wright et al., 2004). Within 2 arcmin of W3(OH) are over 100 near-IR sources that are presumed to be low-mass stars. W3(OH) and its close-by companion, W3(H2O) (Turner and Welch, 1984), are two very dense hot cores surrounded by cooler material (Wilson et al., 1991). The LSR velocities (near −48 km/s) and linewidths (∼5 km/s) for formamide in this source are typical for molecules in the cooler gas (10–60 K; Kim et al., 2006). Formamide had been previously seen in W3(H2O), which is 5 arcsec away from our position (Bisschop et al., 2007).

5. Analysis

For each source in which more than three rotational transitions were observed, a column density was calculated with the rotation diagram method, which assumes local thermodynamic equilibrium conditions (see Turner, 1991). Local thermodynamic equilibrium implies optically thin emission as well as a homogeneous distribution of molecules in an area of constant temperature and density. It is a reasonable approximation for molecules with extended distributions, as exhibited by formamide in Orion, where it appears to arise from the more quiescent ridge material that traces the general molecular cloud. The molecule thus is likely produced by quiescent cloud chemistry and might be expected to be extended in other sources as well. Therefore, assuming a beam-filling factor of 1 for all the clouds studied here is reasonable. However, if beam dilution plays a role for the more distant clouds, the net effect would be to raise the column density and abundance of NH2CHO in those objects, increasing the availability of the molecule.

The rotational diagram method is based on the following formula for total molecular column density NT:

|

(1) |

Here, S is the line strength of a given transition, μ the molecular dipole moment, Qrot the rotational partition function, Eu the energy of the upper level of the transition, and Trot the rotational temperature. The above equation can be rearranged to be the formula employed in the rotational diagram method:

|

(2) |

The quantity on the left, also called log I, is then plotted versus Eu for each transition measured. The slope of the resulting line yields Trot, and the y intercept is log(NT/Qrot). Calculation of the partition function then directly leads to the total column density. The partition function for asymmetric tops with no particular symmetry is estimated by the following formula (Turner, 1991):

|

(3) |

Here A, B, and C are the rotational constants of the molecule, in this case formamide, and T=Trot.

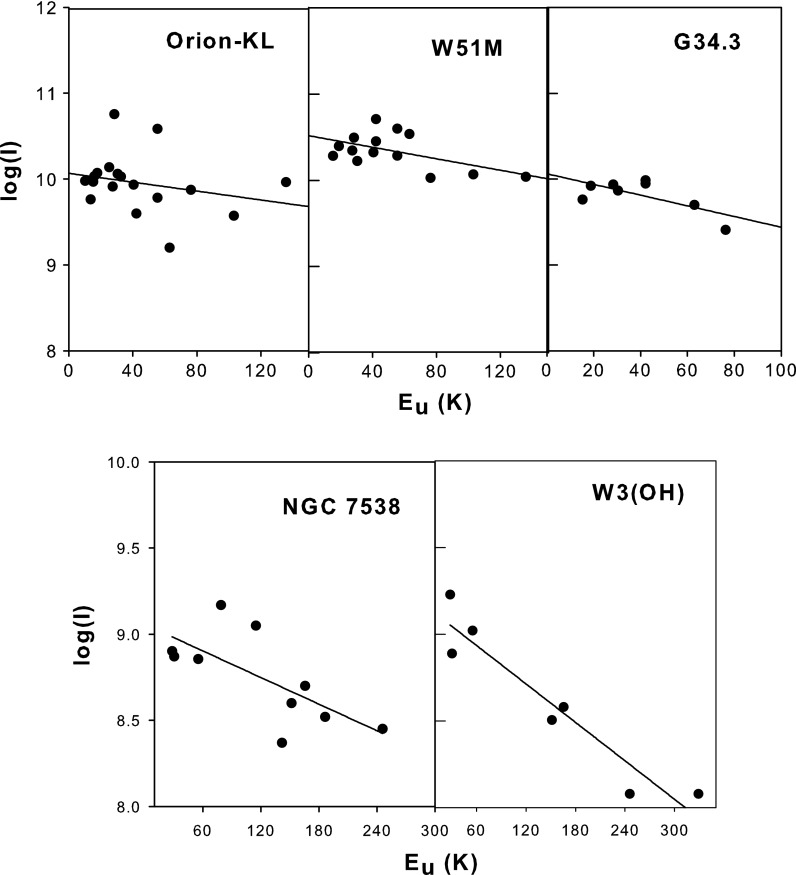

Figure 6a displays the rotational diagrams derived for Orion-KL, G34.3, and W51M. Figure 6b shows the rotational diagrams for W3(OH) and NGC 7538, generated by combining these data with those of Bisschop et al. (2007). As expected for optically thin emission, the points corresponding to the measured transitions approximately fall along a straight line. The derived rotational temperatures and column densities obtained from this method are presented in Table 4. As is seen in the table, the rotational temperatures fall in the range of 70–177 K for NH2CHO, indicating its presence in warm gas.

FIG. 6.

Rotational diagrams for Orion-KL, W51M, G34.3 (upper panels), and NGC 7538, W3(OH) (lower panels). The y axis represents log I, where  . The rotational diagrams for NGC 7538 and W3(OH) were constructed by combining our measurements with those of Bisschop et al. (2007). Rotational temperatures derived from the plots lie in the range of 70–177 K, indicating that formamide is present in warm gas in molecular clouds.

. The rotational diagrams for NGC 7538 and W3(OH) were constructed by combining our measurements with those of Bisschop et al. (2007). Rotational temperatures derived from the plots lie in the range of 70–177 K, indicating that formamide is present in warm gas in molecular clouds.

Table 4.

Column Densities and Abundances of NH2CHO in Molecular Clouds

| Source | Ntot(cm−2) | Trot(K) | N(H2) (cm−2) | f(NH2CHO/H2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orion-KL | 4.7 (1.7)×1013 | 168 | 1×1024,a | 5×10−11 |

| W51M | 9.1 (2.2)×1013 | 130 | 1×1024,a | 1×10−10 |

| G34.3 | 1.2 (0.4)×1013 | 70 | 5×1023,a | 4×10−11 |

| NGC 7538 | 4.8 (1.5)×1012 | 177 | 1×1023,a | 5×10−11 |

| M17 SW | 2.6 (0.9)×1012 | 70b | 2×1023,c | 1×10−11 |

| W3(OH) | 3.3 (0.8)×1012 | 124 | 1×1023,a | 3×10−11 |

| DR21(OH) | 1.1 (0.5)×1012 | 70b | 1×1023,a | 1×10−11 |

| SgrB2(N) | 1.7×1014,d | 26 | 3×1024,d | 5×10−11 |

| 4.0×1014,e | 134 | 3×1024,e | 1.3×10−10 | |

| SgrB2(OH) | 7.2 (0.3)×1013,f | 13f | 1×1024,g | 7×10−11 |

| G24.78h | 1.4×1013 | 169 | 4×1023 | 3×10−11 |

| G75.78h | 2.5×1012 | 77 | 1×1023 | 2×10−11 |

| NGC 6334 IRS1h | 3.2×1013 | 166 | 2×1023 | 1×10−10 |

| W33 Ah | 1.3×1013 | 45 | 2×1023 | 6×10−11 |

| Comet Hale-Bopp | 1–2×10−12,i |

Apponi and Ziurys, 1997.

Assumed rotational temperature.

Stutzki et al., 1988.

Halfen et al., 2011, cold component.

Halfen et al., 2011, hot component.

Cummins et al., 1986.

Sutton et al., 1991.

Based on rotational diagrams of Bisschop et al. (2007), assuming a uniform beam-filling factor.

Derived from the fractional abundance of formamide relative to H2O, from Bockelee-Morvan et al. (2000). See text.

For the sources when only a few transitions were measured [M17 SW and DR21(OH)], the total column density was calculated analytically from the transition with the highest upper state energy, with the equation

|

(4) |

In this case, a rotational temperature must be assumed; based on the values obtained by the rotational diagram method, Trot ∼ 70 K was used. The resulting column densities calculated by this method are also summarized in Table 4. To complete the sample, included in the table is NT obtained for formamide for the other known sources of this molecule, including SgrB2(N) and SgrB2(OH), as measured by Halfen et al. (2011) and Cummins et al. (1986), and four clouds from Bisschop et al. (2007). These values were also determined by the rotational diagram method. A uniform beam-filling factor was assumed in all cases.

6. Discussion

6.1. Abundances and distribution of interstellar NH2CHO

The total column densities obtained for formamide in the seven sources studied are in the range of 0.1–9.1×1013 cm−2. The source with the highest value is W51M, and the smallest is DR21(OH). In comparison, the total column density found in SgrB2(N) is 1.7–4.0×1014 cm−2 (Halfen et al., 2011). Here the range of values reflects the presence of two gas components, one cool and one warm, with Trot ∼ 26 K and 134 K, respectively. In SgrB2(OH), NT ∼ 7.2×1013 cm−2 (Cummins et al., 1986). SgrB2(N) clearly has the largest abundance of formamide, with both components summing to almost 6×1014 cm−2. Note that Sutton et al. (1995) found a column density of 2.4×1014 cm−2 for NH2CHO and Trot ∼ 187 K in the Orion-KL compact ridge, based on 10 higher energy lines in the 0.8 mm region. These authors also found weak emission in NH2CHO arising from the Orion hot core and the southeast plateau. From 19 observed transitions at lower energies, we find 4.7×1013 cm−2 Trot ∼ 168 K, somewhat in agreement. The factor of 5 difference is likely a result of the smaller beam size used by Sutton et al., which samples higher-excitation material.

The abundances derived for formamide, relative to H2, are also shown in Table 4. These values were obtained by comparing the total column densities for NH2CHO with values for H2 from the literature. The abundances lie in the range of 0.1–1×10−10. It appears that the abundance of formamide relative to H2 is constant within one order of magnitude throughout the molecular cloud sample.

Formamide's known presence in 13 sources (Table 4) indicates that it is a fairly common species in molecular clouds associated with high-mass star formation. Its abundance in the Galaxy is illustrated in Fig. 2. Here, the sources of formamide are indicated by a filled circle, whose size is proportional to the [NH2CHO]/[H2] ratio. The molecule is present near the Galactic Center, to as far out as RG ∼ 10 kpc. It is unknown whether it exists in objects at larger galactic distances. H2CO has been observed in gas as far as RG ∼ 20 kpc (Blair et al., 2008). These observations have suggested that the galactic habitable zone (GHZ) could exist near the edges of the Galaxy.

The concept of the GHZ is clearly evolving. Criteria such as metallicity gradients, star formation, and supernova rates have been used to define its location in the Galaxy. Lineweaver et al. (2004), for example, modeled the GHZ as a time-evolving region, at the current time located in a ring roughly between 7 and 9 kpc from the Galactic Center. In this region, the probability of finding complex life is the highest. Prantzos (2008) argued that the whole galactic disk may be suitable for life, when considering the number of Earth-like planets that survive both the formation of “Hot Jupiters” and supernovae explosions. The most recent estimation of the GHZ, from Gowanlock et al. (2011), is based on the number of habitable planets. These authors predicted the GHZ to extend about 12 kpc from the Galactic Center, with the greatest possibility of life at a radius of about 2.5 kpc. At distances DG≤2.5 kpc, however, habitability may sharply decrease as the stellar density rises. The extent of the GHZ of Gowanlock et al. is plotted on Fig. 2. It is interesting to see from the figure that formamide appears to exist throughout the proposed GHZ region.

6.2. Interstellar formation of formamide

The formation process of formamide in molecular clouds is not well understood. The molecule appears to be present near hot cores, in gas that is warm. Halfen et al. (2011) suggested two basic routes to NH2CHO formation. One route involves gas-phase processes, in particular radiative association and ion-molecule reactions that use common and abundant precursors like H2CO and  ; the alternative pathway is via grain chemistry, through hydrogenation and UV processing, followed by the evaporation of the icy grain mantles. It is difficult from our observations to reliably distinguish between these possible synthetic routes, but some insight can be gained from well-studied sources like Orion.

; the alternative pathway is via grain chemistry, through hydrogenation and UV processing, followed by the evaporation of the icy grain mantles. It is difficult from our observations to reliably distinguish between these possible synthetic routes, but some insight can be gained from well-studied sources like Orion.

In the Orion-KL region, the center of the star-forming region is the dense “Hot Core,” where the gas kinetic temperature is greater than 200 K. The chemistry in the Hot Core is thought to be dominated by gas-grain interactions and the subsequent evaporation of ice mantles (Wright et al., 1996). Surrounding this Hot Core is the Plateau, tracing material impacted by powerful outflows from the protostars near the Hot Core and the more quiescent ambient material (Lerate et al., 2008). In the Plateau, shock chemistry is likely to be important. Finally, there is an extended layer of ambient material forming the so-called ridge; the “compact ridge” is material that is heated by the activities near the Hot Core (Ungerechts et al., 1997). Each of these regions displays a different line profile. The VLSR velocities and linewidths indicate that formamide emission likely arises from the warm ridge. Furthermore, the rotational diagram is consistent with one velocity component. These facts would suggest that gas-phase mechanisms lead to formamide in Orion, albeit at warm temperatures.

Quan and Herbst (2007) proposed that NH2CHO is created from the radiative association reaction:

|

(5) |

Dissociative recombination then leads to the neutral product:

|

(6) |

The rate of the radiative association process is not known, however. Halfen et al. (2011) proposed another gas-phase process involving an ion-molecule reaction, followed by dissociative electron recombination:

|

(7) |

|

(8) |

Reaction rates and branching ratios for these reactions are also unknown. In the best case scenario, Reaction 7 would proceed near the Langevin rate of ∼2×10−9 cm3/s, while typical dissociation electron recombination rates, as would apply to Eq. 8, are ∼10−7 cm3/s (Bardsley and Biondi, 1970). The above scheme in principle could be feasible, if the branching ratios were favorable.

Garrod et al. (2008) had an alternative mechanism for gas-phase formamide production, namely, neutral-neutral reactions. These processes often have a small barrier, which could be overcome in the warmer gas that characterizes NH2CHO, making it an attractive possibility. The reaction involves formaldehyde and the NH2 radical, both abundant species in interstellar clouds (e.g., Persson et al., 2012):

|

(9) |

Because one of the reactants is a radical, the process should be faster than typical neutral-neutral pathways. The rate could be as high as k ∼10−11 cm3/s (Woodall et al., 2007).

Another avenue for NH2CHO synthesis would involve dust grain reactions. The tentative identification of formamide features in the ISO-SWS infrared spectra of interstellar ices in the young stellar objects NGC 7539 IRS9 (Raunier et al., 2004) and W33A (Schutte et al., 1999) suggests its presence on dust grain surfaces. It is postulated that hydrogenation of HNCO leads to formamide on grains (Charnley and Rodgers, 2009). Experimental irradiation of CO- and NH3-rich interstellar ice analogues has also been shown to produce this molecule (Jones et al., 2011). Garrod et al. (2008) generated formamide in ices by hydrogenation of OCN and also by the reaction of HCO and NH2. However, these processes lead to an overproduction of formamide, with f=1.3–2.4×10−6 (Garrod et al., 2008), at least 4 orders of magnitude more abundant than in the most favorable source.

6.3. Links to comets, asteroids, and early Earth

During the formation of the Solar System, gas-phase formamide may have condensed and been incorporated in accreting asteroids, planetesimals, comets, and meteorites. Oort Cloud comets are believed to be residuals of planetary accretion and therefore reflect the pristine composition of grains and icy bodies in the presolar nebula (Irvine et al., 2000). Such objects could contain unprocessed formamide from the nascent molecular cloud in which the Solar System formed. Observational evidence of comet Hale-Bopp supports this hypothesis. Hale-Bopp, discovered in 1995, is the brightest Oort Cloud comet yet to be studied. Several organics were detected by millimeter radio observations, including formamide, which had an abundance, relative to water, of [NH2CHO]/[H2O] ∼ 1–2×10−4 (Bockelee-Morvan et al., 2000). This abundance is not negligible.

For comparison with the interstellar abundance measured here, a value for the [H2O]/[H2] ratio in the molecular cloud predating our solar system must be assumed. Modeling the physical and chemical properties of H2O and using observations of the 557 GHz line from the Submillimeter Wave Astronomy Satellite as a benchmark, Hollenbach et al. (2009) estimated the average abundance of water vapor within a dense, star-forming cloud to be [H2O]/[H2] ∼ 10−8. The [NH2CHO]/[H2] would then be around 1–2×10−12 for the Oort Cloud comets, if Hale-Bopp is representative. This value is within an order of magnitude of the abundances observed in molecular clouds (see Table 4).

It is not clear whether formamide in comets is pristine interstellar material or produced from chemical reactions in the coma on solar approach (Irvine et al., 2000). It has been shown that the abundance of HCN and HNC within comets is highly dependent on their distance from the Sun and may not reflect interstellar abundances (Biver et al., 1997; Rodgers and Charnley, 1998). The similarity between the gas-phase abundances for NH2CHO in the interstellar medium and in Hale-Bopp, however, suggests a possible connection between interstellar clouds and comets.

Meteorites are also known to be sources of potentially prebiotic compounds (Pizzarello and Shock, 2010). Alkyl amides, such as acetamide, propionamide, and more complex species up to 12 carbon atoms have been identified in carbonaceous chondrites, although exact quantities have not been determined (Cooper and Cronin, 1995; Pizzarello et al., 2006). However, smaller amides, such as formamide, are easily lost in the preparation process and are difficult to detect in meteoritic material. It is perhaps not unreasonable to assume that formamide is part of the meteoritic amide suite. Interplanetary dust particles are another source of interstellar organic compounds. However, due to their size, they are more difficult to analyze, and few techniques have the sensitivity and spatial resolution to study the organic content of IDPs in detail. The methods typically are only functional group–specific but seem to indicate the presence of amides or amines in IDPs (Pizzarello et al., 2006).

The large prebiotic inventory of comets and meteorites has led to a renewed interest in estimating the role of extraterrestrial material in the emergence of life on Earth (e.g., Whittet, 1997). The objects delivering extraterrestrial material can be classified into three general categories according to their size: large impactors, meteorites, and IDPs (e.g., Pasek and Lauretta, 2008). Upon entry in the atmosphere, the organic matter in such objects faces multiple hazards, such as vaporization and destruction by heating (Anders, 1989; Pasek and Lauretta, 2008). However, it is now known that meteorites that survive passage through Earth's atmosphere without breaking apart do not lose their organic content, as it is preserved by an icy fusion crust (e.g., Pizzarello et al., 2001).

It can be argued that IDPs are the main contributors of extraterrestrial prebiotic compounds (Anders, 1989; Pasek and Lauretta, 2008). Based on the analysis of the crater record on the Moon, two delivery scenarios can be inferred: a gradual decrease of the flux of impactors after the creation of Earth 4.4 billion years ago (Hartmann, 2003); alternatively, a cataclysmic event at 3.8–4 Ga, where the flux of impactors greatly increased, that is, the Late Heavy Bombardment (Ryder, 2003). Depending on the chosen hypothesis, the flux of prebiotic carbon from IDPs on early, pre-life Earth has been estimated to be in the range of ∼0.1 kg/km2/yr to ∼10 kg/km2/yr (Whittet, 1997; Pasek and Lauretta, 2008).

There has only been one estimate of the IDP flux of prebiotic nitrogen, by Pasek and Lauretta (2008). These authors calculated the influx of extraterrestrial nitrogen delivered to earth from IDPs during the Late Heavy Bombardment to be ∼0.2 kg/km2/yr, or 14.3 mol/km2/yr. Considering the inventory in Hale-Bopp (Bockelee-Morvan et al., 2000), nitrogen-bearing molecules are ∼1.1% of the H2O abundance. Formamide itself is 0.01% and thus about 1% of the nitrogen molar content in Hale-Bopp. If the assumption is made that formamide composes roughly 0.5% of all nitrogen molecules brought to Earth during the Late Heavy Bombardment, then the maximum annual terrestrial flux of formamide from IDP infall is ∼0.07 mol/km2/yr. Even though it is likely that most of this material was deposited in the oceans and thus largely dissolved and diluted, some formamide also could have found its way to the surface of a mineral catalyst or thin freshwater environments.

It is hard to evaluate whether such a flux of NH2CHO would be sufficient to influence prebiotic chemistry. In the case of HCN, concentrations of 10−2 M are needed to produce the tetramer leading to purine synthesis (Orgel, 2004). It is hard to imagine that such a concentration on early Earth could be realized, given the volatility of HCN. On the other hand, mixtures of 10% formamide in water have been shown experimentally to yield purine, adenine, and hypoxanthine at 100°C over a 96 h period (Barks et al., 2010). It is possible that this concentration of formamide in water could have occurred on early Earth, given the low volatility of NH2CHO and the lack of azeotrope mixtures between the two substances. However, formamide would have to be accumulated over a long period of time without disruption—an improbable scenario. It is therefore unlikely that the formamide flux from IDPs would be sufficient to start significant production of purines in the RNA world.

Locally, however, meteorites also may have delivered a significant amount of NH2CHO (Pasek and Lauretta, 2008). Renazzo-type or CR carbonaceous chondrites are remarkably rich in small, nitrogen-bearing soluble organic molecules, including ammonia, amino acids, and amines (Pizzarello et al., 2011). Recently, GRA95229 and other meteorites were found to contain large amounts of ammonia in the insoluble organic material, or IOM (Pizzarello and Williams, 2012). HCN now has also been extracted from the Murchison meteorite (Pizzarello, 2012). These results suggest that meteorites were the main source of nitrogen-containing material needed for prebiotic synthesis. Formamide could be part of this nitrogen source.

If the atmosphere during the early Earth epoch was denser than it is today, say of the order of 10 bar, the organic content of impactors up to 100 m in size would be preserved (Whittet et al., 1997). A carbonaceous chondrite fragment of 1 m in radius, hitting early Earth at a speed of 15 km/s and at an angle of 15° from the horizontal (Pierazzo and Chyba, 1999), would have formed a crater of ∼2.5×103 m2, in accordance with the crater energy-diameter scaling law given by Popova et al. (2003). Assuming this hypothetical meteorite to have the same density as that of Murchison (2.5 g/cm3; Fuchs et al., 1973), it would have delivered a total mass of ∼1.05×104 kg of material, or 4.2 kg/m2. Considering a meteorite such as GRA 95229, about 1% of this mass would be in the IOM, or about 105 kg. The amount of nitrogen found in the IOM phase of GRA 95229 is about 27.9 μg/mg (Pizzarello et al., 2011). Roughly speaking, the IOM composes about 70% of the organic material in typical carbonaceous chondrites, with 30% in the soluble organic material phase. Therefore, about 12.0 μg/mg of nitrogen is contained in the soluble organic material, assuming that the nitrogen content is the same in both phases. If about 0.5% of the molar nitrogen content is contained in the form of formamide (approximately the percent in comet Hale Bopp), then of the original ∼104 kg of material, ∼0.45 mol of NH2CHO would be delivered to Earth in one impact, or 0.18 mmol/m2. Given formamide's relatively high stability, with a low boiling point (210°C), it is conceivable that on local sites, over several years, the concentration of formamide could reach levels necessary for prebiotic synthesis. As mentioned, 10% formamide in water can produce detectable amounts of purines (Barks et al., 2010).

7. Conclusion

Formamide has been proposed as a unique, prebiotic source of nucleobases and informational polymers. Past work has shown that the compound has the necessary reactivity and stability to fulfill this role. This study of interstellar formamide indicates that the molecule is a common constituent of star-forming regions and is prevalent within the GHZ. The abundance found in molecular clouds is comparable to what has been observed in comet Hale Bopp, suggesting that formamide is incorporated into planetesimals in the pre-solar nebula. Oort Cloud comets may be a potential source of prebiotic formamide, as could be meteorites and IDPs. The flux of formamide brought to Earth during the period of the Late Heavy Bombardment by IDPs could have been on average 0.07 mol/km2/yr, and a single meteorite impact could deliver as much as a few tenths of a millimole per square meter. Considering the low volatility and hydrolysis rate of formamide, these amounts are not negligible and may have contributed importantly to the synthesis of the first prebiotic polymers.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the ARO for making these observations possible. This work was supported by NASA Exobiology Grant NNX10AR83G and NSF grant AST-1140030 from the University Radio Observatories program.

Abbreviations

ARO, Arizona Radio Observatory; GHZ, galactic habitable zone; IDPs, interplanetary dust particles; IOM, insoluble organic material; LSR, local standard of rest; PDR, photon-dominated region; SMT, Submillimeter Telescope.

References

- Anders E. Pre-biotic organic matter from comets and asteroids. Nature. 1989;342:255–257. doi: 10.1038/342255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apponi A.J. Ziurys L.M. New observations of the [HCO+/HOC+] ratio in dense molecular clouds. Astrophys J. 1997;481:800–808. [Google Scholar]

- Apponi A.J. Pesch T.C. Ziurys L.M. Detection of HOC+ toward the Orion Bar and M17 SW: enhanced abundances in photon-dominated regions? Astrophys J. 1999;519:89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bardsley J.N. Biondi M.A. Dissociative recombination. Advances in Atomic and Molecular Physics. 1970;6:1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Barks H.L. Buckley R. Grieves G.A. Di Mauro E. Hud N.V. Orlando T.M. Guanine, adenine, and hypoxanthine production in UV-irradiated formamide solutions: relaxation of the requirements for prebiotic purine nucleobase formation. Chembiochem. 2010;11:1240–1243. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell M.B. Avery L.W. Watson J.K.G. A spectral-line survey of W51 from 17.6 to 22.0 GHz. Astrophys J Suppl Ser. 1993;86:211–233. [Google Scholar]

- Bisschop S.E. Jorgensen J.K. van Dishoeck E.F. Wachter E.B.M. Testing grain-surface chemistry in massive hot-core regions. Astron Astrophys. 2007;465:913–929. [Google Scholar]

- Biver N. Bockelee-Morvan D. Colom P. Crovisier J. Davies J.K. Dent W.R.F. Despois D. Gerard E. Lellouch E. Rauer H. Moreno R. Paubert G. Evolution of the outgassing of comet Hale-Bopp (C/1995 O1) from radio observations. Science. 1997;275:1915–1918. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair S.K. Magnani L. Brand J. Wouterloot J.G.A. Formaldehyde in the far outer galaxy: constraining the outer boundary of the galactic habitable zone. Astrobiology. 2008;8:59–73. doi: 10.1089/ast.2007.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake G.A. Sutton E.C. Masson C.R. Phillips T.G. The rotational emission-line spectrum of Orion A between 247 and 263 GHz. Astrophys J Suppl Ser. 1986;60:357–374. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco S. Lopez J.C. Lesarri A. Alonso J.L. Microsolvation of formamide: a rotational study. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12111–12121. doi: 10.1021/ja0618393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockelee-Morvan D. Lis D.C. Wink J.E. Despois D. Crovisier J. Bachiller R. Benford D.J. Biver N. Colom P. Davies J.K. Gérard E. Germain B. Houde M. Mehringer D. Moreno R. Paubert G. Phillips T.G. Rauer H. New molecules found in comet C/1995 O1 (Hale-Bopp) Astron Astrophys. 2000;353:1101–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler C.J. Moore T.J.T. Mountain C.M. Yamashita T. The excitation and kinematics of DR21(OH) from observations of CS. Mon Not R Astron Soc. 1993;261:694–704. [Google Scholar]

- Charnley S.B. Rodgers S.D. Theoretical models of complex molecule formation on dust. In: Meech K.J., editor; Keane J.V., editor; Mumma M.J., editor; Siefert J.L., editor; Werthimer D.J., editor. Bioastronomy 2007: Molecules, Microbes, and Extraterrestrial Life, ASP Conference Series. Vol. 420. Astronomical Society of the Pacific; San Francisco: 2009. pp. 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cleaves J.H. Nelson K.E. Miller S.L. The prebiotic synthesis of pyrimidines in frozen solution. Naturwissenschaften. 2006;93:228–231. doi: 10.1007/s00114-005-0073-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G.W. Cronin J.R. Linear and cyclic aliphatic carboxamides of the Murchison meteorite: hydrolyzable derivatives of amino acids and other carboxylic acids. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1995;59:1003–1015. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(95)00018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo G. Saladino R. Crestini C. Ciciriello F. Di Mauro E. Formamide as the main building block in the origin of nucleic acids. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7(Suppl 2):S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-S2-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins S.E. Linke R.A. Thaddeus P. A survey of Sagittarius B2. Astrophys J Suppl Ser. 1986;60:819–878. [Google Scholar]

- De Buizer J.M. Minier V. Investigating the nature of the dust emission around massive protostar NGC 7538 IRS 1: circumstellar disk or outflow? Astrophys J. 2005;628:151–154. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs L.H. Olsen E. Jensen K.J. Vol. 10. Smithsonian Institution Press; Washington, DC: 1973. Mineralogy, Mineral-Chemistry, and Composition of the Murchison (C2) Meteorite, Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Garrod R.T. Herbst E. Formation of methyl formate and other organic species in the warm up phase of hot molecular cores. Astron Astrophys. 2006;457:927–936. [Google Scholar]

- Garrod R.T. Widicus Weaver S.L. Herbst E. Complex chemistry in star-forming regions: an expanded gas-grain warm-up chemical model. Astrophys J. 2008;682:283–302. [Google Scholar]

- Genzel R. Becklin E.E. Wynn-Williams C.G. Moran J.M. Reid M.J. Jaffe D.T. Downes D. Infrared and radio observations of W51: another Orion-KL at a distance of 7 kiloparsecs? Astrophys J. 1982;255:527–535. [Google Scholar]

- Gowanlock M.G. Patton D.R. McConnell S.M. A model of habitability within the Milky Way Galaxy. Astrobiology. 2011;11:855–873. doi: 10.1089/ast.2010.0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfen D.T. Ilyushin V. Ziurys L.M. Formation of peptide bonds in space: a comprehensive study of formamide and acetamide in Sgr B2(N) Astrophys J. 2011;743:60. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann W.K. Megaregolith evolution and cratering cataclysm models—lunar cataclysm as a misconception (28 years later) Meteorit Planet Sci. 2003;38:579–593. [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbach D. Kaufman M.J. Bergin E.A. Melnick G.J. Water, O2 and ice in molecular clouds. Astrophys J. 2009;690:1497–1521. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine W.M. Schloerb F.P. Crovisier J. Fegley B. Mumma M.J. Comets: a link between interstellar and nebular chemistry. In: Mannings V., editor; Boss A.P., editor; Russel S.S., editor. Protostars and Planets IV. University of Arizona Press; Tucson, AZ: 2000. pp. 1159–1200. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson L.E.B. Andersson C. Ellder J. Friberg P. Hjalmarson A. Hoglund B. Irvine W.M. Olofsson H. Rydbeck G. Spectral scan of Orion A and IRC+10216 from 72 to 91 GHz. Astron Astrophys. 1984;130:227–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B.M. Bennett C.J. Kaiser R.I. Mechanistical studies on the production of formamide within interstellar ice analogs. Astrophys J. 2011;734:78. [Google Scholar]

- Kameya O. Hasegawa T.I. Hirano N. Tosa M. Taniguchi Y. Takakubo K. CS and C34S observations of the NGC 7538 molecular cloud. Publ Astron Soc Jpn Nihon Tenmon Gakkai. 1986;38:793–810. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.D. Cho S.H. Chung H.S. Kim H.R. Roh D.G. Kim H.G. Minh Y.C. Minn Y.K. A spectral line survey of G34.3+0.15 at 3 millimeters (84.7–115.6 GHz) and 2 millimeters (123.5–155.3 GHz) Astrophys J Suppl Ser. 2000;131:483–504. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S-J. Kim H-D. Lee Y. Minh Y.C. Balasubramanyam R. Burton M.G. Millar T.J. Lee D-W. A molecular line survey of W3(OH) and W3 IRS 5 from 84.7 to 115.6 GHz: observational data and analyses. Astrophys J Suppl Ser. 2006;162:161–206. [Google Scholar]

- Kryvda A.V. Gerasimov V.G. Dyubko S.F. Alekseev E.A. Motiyenko R.A. New measurements of the microwave spectrum of formamide. J Mol Spectrosc. 2009;254:28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lerate M.R. Yates J. Viti S. Barlow M.J. Swinyard B.M. White G.J. Cernicharo J. Goicoechea J.R. Physical parameters for Orion-KL from modeling its ISO high-resolution far-IR CO line spectrum. Mon Not R Astron Soc. 2008;387:1660–1668. [Google Scholar]

- Lineweaver C.H. Fenner Y. Gibson B.K. The galactic habitable zone and the age distribution of complex life in the Milky Way. Science. 2004;303:59–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1092322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald G.H. Gibb A.G. Habing R.J. Millar T.J. A 330–360 GHz spectral survey of G34.3+0.15. I. Data and physical analysis. Astron Astrophys Suppl Ser. 1996;119:333–367. [Google Scholar]

- Mookerjea B. Casper E. Mundy L.G. Looney L.W. Kinematics and chemistry of the hot molecular core in G34.26+0.15 at high resolution. Astrophys J. 2007;659:447–458. [Google Scholar]

- Nummelin A. Bergman P. Hjalmarson A. Friberg P. Irvine W.M. Millar T.J. Ohishi M. Saito S. A three-position spectral line survey of Sagittarius B2 between 218 and 263 GHz. II. Data analysis. Astrophys J Suppl Ser. 2000;128:213–243. [Google Scholar]

- Orgel L.E. Prebiotic chemistry and the origin of the RNA world. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;39:99–123. doi: 10.1080/10409230490460765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasek M. Lauretta D. Extraterrestrial flux of potentially prebiotic C, N, and P to early Earth. Orig Life Evol Biosph. 2008;38:5–21. doi: 10.1007/s11084-007-9110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson C.M. De Luca M. Mookerjea B. Olofsson A.O.H. Black J.H. Gerin M. Herbst E. Bell T.A. Coutens A. Godard B. Goicoechea J.R. Hassel G.E. Hily-Blant P. Menten K.M. Müller H.S.P. Pearson J.C. Yu S. Nitrogen hydrides in interstellar gas. II. Analysis of Herschel/HIFI observations towards W49N and G10.6-04 (W31C) Astron Astrophys. 2012;543:A145. [Google Scholar]

- Pierazzo E. Chyba C.F. Amino acid survival in large cometary impacts. Meteorit Planet Sci. 1999;34:909–918. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzarello S. Hydrogen cyanide in the Murchison meteorite. Astrophys J. 2012;754 doi: 10.1088/2041-8205/754/2/L27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzarello S. Shock E. The organic composition of carbonaceous meteorites: the evolutionary story ahead of biochemistry. In Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzarello S. Williams L.B. Ammonia in the early Solar System: an account from carbonaceous meteorites. Astrophys J. 2012;749 doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/749/2/161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzarello S. Huang Y. Becker L. Poreda R.J. Nieman R.A. Cooper G. Williams M. The organic content of the Tagish Lake meteorite. Science. 2001;293:2236–2239. doi: 10.1126/science.1062614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzarello S. Cooper G.W. Flynn G.J. The nature and distribution of the organic material in carbonaceous chondrites and interplanetary dust particles. In: Lauretta D.S., editor; McSween H.Y., editor. Meteorites and the Early Solar System II. University of Arizona Press; Tucson, AZ: 2006. pp. 625–651. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzarello S. Williams L.B. Lehman J. Holland G.P. Yarger J.L. Abundant ammonia in primitive asteroids and the case for possible exobiology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4303–4306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014961108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popova O. Nemtchinov I. Hartmann W.K. Bolides in the present and past martian atmosphere and effects on cratering processes. Meteorit Planet Sci. 2003;38:905–925. [Google Scholar]

- Prantzos N. On the “galactic habitable zone.”. Space Sci Rev. 2008;135:313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Quan D. Herbst E. Possible gas-phase syntheses for seven neutral molecules studied recently with the Green Bank Telescope. Astron Astrophys. 2007;474:521–527. [Google Scholar]

- Raunier S. Chiavassa T. Duvernay F. Borget F. Aycard J.P. Dartois E. D'Hendecourt L. Tentative identification of urea and formamide In ISO-SWS infrared spectra of interstellar ices. Astron Astrophys. 2004;416:165–169. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers S.D. Charnley S.B. HNC and HCN in comets. Astrophys J. 1998;501:L227–L230. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin R.H. Swenson G.W. Benson R.C. Tigelaar H.L. Flygare W.H. Microwave detection of interstellar formamide. Astrophys J. 1971;169:L39–L44. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder G. Bombardment of the Hadean Earth: wholesome or deleterious? Astrobiology. 2003;3:3–6. doi: 10.1089/153110703321632390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saladino R. Crestini C. Ciciriello F. Costanzo G. Di Mauro E. About a formamide-based origin of informational polymers: syntheses of nucleobases and favourable thermodynamic niches for early polymers. Orig Life Evol Biosph. 2006;36:523–531. doi: 10.1007/s11084-006-9053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez R.A. Ferris J.P. Orgel L.E. Studies in prebiotic synthesis: II. Synthesis of purines precursors and amino acids from aqueous hydrogen cyanide. J Mol Biol. 1967;30:223–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutte W.A. Boogert A.C.A. Tielens A.G.G.M. Whittet D.C.B. Gerakines P.A. Chiar J.E. Ehrenfreund P. Greenberg J.M. van Dishoeck E.F. de Graauw Th. Weak ice absorption features at 7.24 and 7.41 μm in the spectrum of the obscured young stellar object W33A. Astron Astrophys. 1999;343:966–976. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro R. Comments on “concentration by evaporation and the prebiotic synthesis of cytosine.”. Orig Life Evol Biosph. 2002;32:275–278. doi: 10.1023/a:1016582308525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutzki J. Stacey G.J. Genzel R. Harris A.I. Jaffe D.T. Lugten J.B. Submillimeter and far infrared line observations of M17 SW: a clumpy molecular cloud penetrated by ultraviolet radiation. Astrophys J. 1988;332:379–399. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton E.C. Jaminet P.A. Danchi W.C. Blake G.A. Molecular line survey of Sagittarius B2(M) from 330 to 355 GHz and comparison with Sagittarius B2(N) Astrophys J Suppl Ser. 1991;77:255–285. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton E.C. Peng R. Danchi W.C. Jaminet P.A. Sandell G. Russel A.P.G. The distribution of molecules in the core of OMC-1. Astrophys J Suppl Ser. 1995;97:455–496. [Google Scholar]

- Turner B.E. A molecular line survey of Sagittarius B2 and Orion-KL from 70 to 115 GHz II. Analysis of the data. Astrophys J Suppl Ser. 1991;76:617–686. [Google Scholar]

- Turner J.L. Welch W.J. Discovery of a young stellar object near the water masers in W3(OH) Astrophys J. 1984;287:81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ungerechts H. Bergin E.A. Goldsmith P.F. Irvine A.M. Schloerb F.P. Snell R.L. Chemical and physical gradients along the OMC-1 ridge. Astrophys J. 1997;482:245–266. doi: 10.1086/304110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittet D.C.B. Is extraterrestrial organic matter relevant to the origin of life on Earth? Orig Life Evol Biosph. 1997;27:249–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T.L. Johnston K.J. Mauersberger R. The internal structure of molecular clouds II. The W3(OH)/W3(H2O) region. Astron Astrophys. 1991;251:220–230. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T.L. Hanson M.M. Muders D. Two molecular clouds near M17. Astrophys J. 2003;590:895–905. [Google Scholar]

- Woodall J. Agundez M. Markwick-Kemper A.J. Millar T.J. The UMIST database for astrochemistry 2006. Astron Astrophys. 2007;466:1197–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Wright M.C.H. Plambeck R.L. Wilner D.J. A multiline aperture synthesis study of Orion-KL. Astrophys J. 1996;469:216–237. [Google Scholar]

- Wright M.M. Gray M.D. Diamond P.J. The OH ground-state masers in W3(OH) I. Results for 1665 MHz. Mon Not R Astron Soc. 2004;350:1253–1271. [Google Scholar]

- Wright M. Zhao J-H. Sandell G. Corder S. Goss W.M. Zhu L. Observations of a high mass protostar in NGC 7538 S. Astrophys J. 2012;746:187–189. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata L.A. Loinard L. Su Y.-N. Rodriguez L.F. Menten K.M. Patel N. Galvan-Madrid R. Millimeter multiplicity in DR21(OH): outflows, molecular cores, and envelopes. Astrophys J. 2012;744:86–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ziurys L.M. McGonagle D. The spectrum of Orion-KL at 2 millimeters (150–160 GHz) Astrophys J Suppl Ser. 1993;89:155–187. doi: 10.1086/191842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]