SUMMARY

The fundamental importance of the hypothalamus in the regulation of autonomic and cardiovascular functions is well established. However, the molecular processes involved are not well understood. Here, we show that the mammalian (or mechanistic) target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling in the hypothalamus is tied to the activity of the sympathetic nervous system and cardiovascular function. Modulation of mTORC1 signaling caused dramatic changes in sympathetic traffic, blood flow and arterial pressure. Our data also demonstrate the importance of hypothalamic mTORC1 signaling in transducing the sympathetic and cardiovascular actions of leptin. Moreover, we show that PI3K pathway links the leptin receptor to mTORC1 signaling and changes in its activity impacts the sympathetic traffic and arterial pressure. These findings establish mTORC1 activity in the hypothalamus as a key determinant of sympathetic and cardiovascular regulation and suggest that dysregulated hypothalamic mTORC1 activity may influence the development of cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: mTOR signaling, hypothalamus, sympathetic nervous system, arterial pressure

INTRODUCTION

The evolutionary conserved mTOR protein belongs to the phosphatidylinositol kinase–related kinase family (Laplante and Sabatini, 2012). mTOR is critically involved in the regulation of a number of cellular functions, including protein synthesis, cell growth and proliferation, ribosome and mitochondria biogenesis, cytoskeleton organization and autophagy (Hay and Sonenberg, 2004; Mamane et al., 2006; Wullschleger et al., 2006). mTOR activity is modulated by various cues arising from growth factors, stress, nutrients and energy status.

Active mTOR interacts with several other proteins leading to the formation of two functionally distinct large complexes (mTORC1 and mTORC2) that can be distinguished from each other based on their unique compositions and the downstream pathways associated with each complex (Wullschleger et al., 2006; Laplante and Sabatini, 2012). For instance, activated mTORC1 causes the phosphorylation of S6 kinase (S6K) and its downstream effector, the ribosomal protein S6 (Laplante and Sabatini, 2012).

In the central nervous system, the mTOR pathway contributes to the regulation of a wide range of processes including synaptic plasticity, neuronal excitability, learning and memory (Jaworski and Sheng, 2006; Swiech et al., 2008). Dysregulated mTOR signaling has been implicated in a number of neurological disorders such as tuberous sclerosis and epilepsy as well as neurodegenerative disease including Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease (Bove et al., 2011; Swiech et al., 2008). The proven beneficial effects of rapamycin and its analogues in cellular and animal models of various neurodegenerative diseases have led to significant efforts to pharmacologically target the mTOR pathway in neurodegeneration (Bove et al., 2011).

Recently, increasing attention has been paid to mTOR signaling in the hypothalamus, a region that has a well-known role in homeostasis by coordinating the regulation of several physiological processes. For instance, although mTOR and S6K are widely expressed in the brain, modulation of their activity by changes in body energy status was found to be limited to specific neurons of the hypothalamus in rats (Cota et al., 2006). Altering mTORC1 signaling in the hypothalamus affected food intake and body weight (Cota et al., 2006; Blouet et al., 2008), peripheral insulin sensitivity (Ono et al., 2008) and reproductive function (Roa et al., 2009). Moreover, hypothalamic mTORC1 was found to be critically involved in mediating the anorectic and weight-reducing effects of leptin (Cota et al., 2006). The well-established role of the hypothalamus in autonomic and cardiovascular regulation (Dampney et al., 2005; Guyenet, 2006; Nakamura et al., 2009) led us to hypothesize that hypothalamic mTORC1 signaling is involved in the control of the sympathetic nervous system and cardiovascular function.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Leucine Increases Hypothalamic mTORC1, Sympathetic Outflow and Arterial Pressure

To test our hypothesis, we took advantage of the unique ability of leucine, a branched amino-acid, to activate mTORC1 signaling (Avruch et al., 2009; Han et al., 2012). In hypothalamic GT1-7 cells, leucine stimulated S6K in a time-dependent manner (Figure 1A) as reported previously (Morrison et al., 2007; Cota et al., 2006; Blouet et al., 2008). We also performed in vivo experiments in rats to test the effect of leucine when administered intracerebroventricularly (ICV) into the 3rd cerebral ventricle, which is anatomically adjacent to the hypothalamus. As previously shown (Cota et al., 2006; Blouet et al., 2009), ICV leucine (5 μg) activated hypothalamic mTORC1 signaling as indicated by the robust and time-dependent increase in phosphorylated levels of S6K (p-S6K, Figure 1B) and S6 (p-S6, Figure 1C). Of note, the increase in mTORC1 signaling was restricted to the hypothalamus, as no increase in p-S6K and p-S6 was detected in extra-hypothalamic regions such as the hippocampus, cortex, and brainstem (Figure S1A–B and data not shown). Thus, 3rd ventricle ICV leucine activates the mTORC1 signaling pathway specifically in the hypothalamus.

Figure 1. Sympathetic and hemodynamic responses evoked by hypothalamic action of leucine.

(A) Representative Western blots of p-S6K (Thr389) and total S6K in hypothalamic GT1-7 cells that were treated with 10 mM of leucine or valine (n=5 each).

(B–C) Effects of ICV injection of leucine (5 μg) on p-S6K (Thr389, B) and p-S6 (Ser240/244, C) in the mediobasal hypothalamus of Sprague–Dawley rats (n=3 each).

(D–F) Renal SNA response to ICV leucine and valine in rats (n=13 each). Representative neurograms of renal SNA recording at baseline and 6 h after ICV leucine (5 μg, D); time–course of renal SNA responses to ICV vehicle vs. leucine (5 μg, E) and average of last hour of renal SNA (F) after ICV vehicle, leucine (1 or 5 μg), or valine (5 μg).

(G–H) Arterial pressure response to ICV leucine and valine in rats (n=13 each). Time-course of mean arterial pressure (MAP) response to ICV vehicle vs. leucine (5 μg, G) and averages of last hour of MAP (H) following ICV vehicle, leucine (1 or 5 μg), or valine (5 μg).

(I) Effect of ICV injection of 5 μg of leucine or valine on blood flow (conductance) recorded from various vascular beds in rats (averages of last hour of recordings are displayed, n=13–15).

(J) Peak decrease in MAP in ICV vehicle– and leucine (5 μg)–treated rats after a bolus intravenous injection of hexamethonium (1 μg/g body weight, n=5–6).

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 vs. vehicle, †P<0.01 vs. vehicle and valine.

We then assessed the sympathetic and hemodynamic effects of hypothalamic mTORC1 activation with ICV leucine. Sympathetic nerve activity (SNA) was recorded directly from the nerve fibers subserving the kidney and measured simultaneously with arterial pressure in anesthetized rats (Rahmouni and Morgan, 2007). We found that ICV administration of leucine (1 and 5 μg) caused a significant and dose-dependent increase in renal SNA (Figure 1D–F). A parallel and dose-related rise in arterial pressure was elicited by ICV leucine (Figure 1G–H). The pressor effect of ICV leucine was reproduced using radiotelemetry measurement in freely moving, conscious rats (Figure S1C-F). Notably, the increase in arterial pressure was associated with a significant decrease in blood flow recorded from various arteries: aortic, iliac, mesenteric and renal, with variable intensity (Figure 1I).

To investigate whether ICV leucine–induced arterial pressure elevation was dependent on the sympathetic outflow, we assessed the effect of ganglionic blockade with hexamethonium (1 μg/g body weight, intravenously). The magnitude of arterial pressure decrease caused by hexamethonium was significantly greater in leucine-treated rats than in controls (Figure 1J), highlighting the importance of the sympathetic transmission in mediating the pressor effect of ICV leucine.

ICV injection of another branched–chain amino acid, valine, which does not activate mTORC1 signaling in GT1-7 cell line (Figure 1A), or mediobasal hypothalamic explants (Figures S1G), failed to alter renal SNA (Figure 1F), arterial pressure (Figure 1H) or regional blood flows (Figure 1I) indicating that the sympathetic and hemodynamic responses to leucine are specific.

It is interesting to note that a previous study reported elevated circulating leucine in hypertensive subjects (Newgard et al., 2009). Moreover, plasma leucine levels correlated with cardiovascular events and even predicted their occurrence (Shah et al., 2010; Shah et al., 2012). These reports combined with our findings suggest circulating leucine as a major cardiovascular risk factor. We therefore investigated whether systemic administration of leucine will alter SNA and arterial pressure in rats. Intravenous infusion of leucine (1 mg/kg) caused a slow but significant increase in renal SNA, with a 76 ± 10% increase in the 6th hour (Figure S1H). This was associated with a 13 ± 4 mmHg elevation in mean arterial pressure (Figure S1I). Notably, transection of the renal nerve distal to the recording site did not affect the sympathetic activation (84 ± 9% increase) caused by intravenous administration of leucine, demonstrating that leucine stimulated efferent rather than afferent sympathetic traffic, which is consistent with a centrally-mediated effect of leucine.

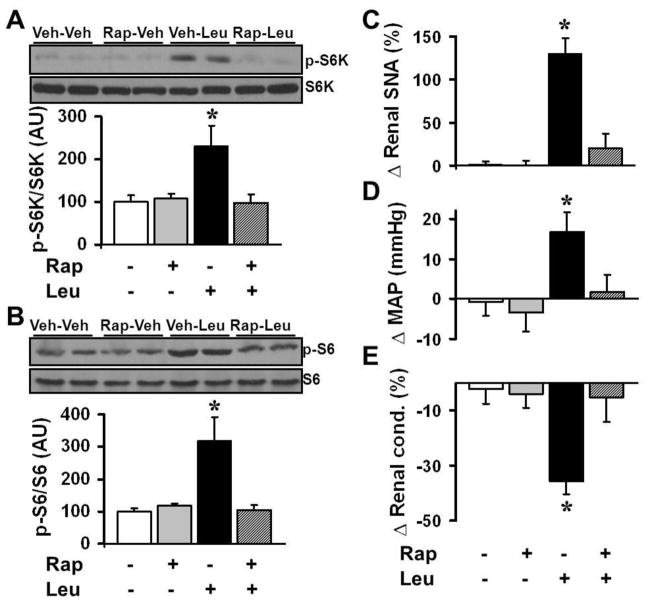

Rapamycin Inhibits the Sympathetic and Cardiovascular Effects of Leucine

To confirm that the hypothalamic effects of leucine are mediated by mTORC1 signaling, we tested the renal SNA and arterial pressure responses to leucine in the presence of rapamycin. As expected, ICV pre-treatment with rapamycin (10 ng) blocked the increase in hypothalamic p-S6K and p-S6 caused by ICV leucine (Figure 2A–B). In addition, ICV pre-treatment with rapamycin abolished leucine-induced increase in both renal SNA (Figure 2C) and arterial pressure (Figure 2D), as well as the reduction in renal blood flow (Figure 2E). Together, these data demonstrate that hypothalamic mTORC1 plays an important role in controlling SNA and cardiovascular function.

Figure 2. The sympathetic and hemodynamic actions of hypothalamic leucine are mediated by mTORC1 signaling.

(A–B) Effects of mTORC1 inhibition with ICV rapamycin (10 ng) on ICV leucine (5 μg) –induced increase in p-S6K (Thr389, A) and p-S6 (Ser240/244, B) in rat mediobasal hypothalamic explants (n=4 each).

(C–E) Effects of ICV pre-treatment with rapamycin (10 ng) on the renal SNA (C), MAP (D) and renal blood flow (E) responses evoked by 5 μg of leucine ICV (n=10–15). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 vs. other groups.

mTORC1 Mediates the Sympathetic and Cardiovascular Actions of Leptin

The mTORC1 pathway has emerged as a critical signaling mechanism of the leptin receptor in the hypothalamus (Cota et al., 2006; Blouet et al., 2008). Given the compelling evidence supporting the notion that brain action of leptin promotes sympathoexcitation and arterial pressure increase (Hall et al., 2010; Harlan et al., 2011a), we hypothesized that mTORC1 activation is required for the sympathetic and hemodynamic responses induced by leptin. In rats, ICV administration of leptin (10 μg) activated hypothalamic mTORC1 signaling (Figure 3A–B). ICV leptin caused no significant change in mTORC1 signaling in extra-hypothalamic regions such as the hippocampus, cortex and brainstem (data not shown). Pre-treatment with rapamycin completely abolished leptin-evoked activation of mTORC1 signaling (Figure 3A–B). Moreover, ICV pre-treatment with rapamycin substantially reduced leptin-induced increase in renal SNA (Figure 3C) and arterial pressure (Figure 3D). We also tested the effects of rapamycin on the sympathetic and hemodynamic effects induced by another stimulus, melanotan II (MTII), which activates the melanocortin 3/4 receptors that have been implicated as downstream mediators of the sympathetic and cardiovascular actions of leptin (Hall et al., 2010; Rahmouni et al., 2003b). However, pre-treatment with rapamycin had no effect on ICV MTII-induced increases in renal SNA or arterial pressure (Figure S2A–B), indicating that blockade of sympathetic and cardiovascular effects of leptin by rapamycin is upstream of the melanocortin system.

Figure 3. Critical role of hypothalamic mTORC1 signaling in the sympathoexcitatory and pressor effects of leptin.

(A–B) Effects of pre-treatment with ICV rapamycin (10 ng) on ICV leptin (10 μg)-induced increase in hypothalamic p-S6K (Thr389, A) and p-S6 (Ser240/244, B) in rats (n=4–5).

(C–D) Renal SNA (C) and MAP (D) responses to ICV leptin (10 μg) in absence or presence of rapamycin (10 ng) administered ICV in rats (n=8 each).

(E) GFP staining (counter-stained with DAPI) in the Arc of a rat that received bilateral microinjection of AdGFP into this nucleus. Bar: 100 μm.

(F–G) Comparison of baseline renal SNA and MAP between rats that received one week earlier AdDNS6K (with AdGFP) or AdGFP alone (control group) hitting the Arc (n=5–11).

(H–I) Renal SNA response to intravenous infusion of leptin (0.75 μg/g body weight) in rats that received AdDNS6K or AdGFP hitting the Arc. I: Renal SNA response to leptin was compared between rats that received AdDNS6K microinjections which “hit” or “missed” the Arc (n=5–11)

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 vs. other group(s).

The evidences implicating the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (Arc) as the site of leptin action to increase sympathetic traffic and arterial pressure (Harlan et al., 2011a; Rahmouni and Morgan, 2007) prompted us to test whether blocking mTORC1 signaling in the Arc is sufficient to inhibit the sympathetic and hemodynamic effects of leptin. To do this, an adenoviral vector expressing a dominant-negative form of S6K (AdDNS6K) (Blouet et al., 2008) was delivered specifically to the Arc via bilateral stereotaxic microinjections. Adenovirus expressing green fluorescent protein (AdGFP) was used as a control and co-injected with the AdDNS6K to facilitate the identification of the infected region (Figure 3E). The effectiveness of AdDNS6K in inhibiting S6K signaling was validated in the hypothalamic GT1-7 cell line and Arc (Figure S2C-D and previous studies by Blouet et al., 2008 and Ono et al., 2008).

We then examined the effect of selectively decreasing mTORC1 signaling in the Arc on the sympathetic response evoked by intravenous administration of leptin (0.75 μg/g). Interestingly, overexpression of DNS6K in the Arc decreased baseline renal SNA and arterial pressure (Figure 3F–G). Of note, these effects are absent in the leptin receptor mutant Zucker rats (Figure S2E–F). We also found that overexpression of DNS6K in the Arc virtually eliminated the renal sympathoexcitation caused by intravenous leptin (Figure 3H–I). Intravenous administration of leptin caused a modest increase in arterial pressure (6 ± 6 mmHg) which was reversed (2 ± 6 mmHg) when Arc mTORC1 signaling was blocked with the DNS6K. Notably, the renal SNA response to leptin in rats that underwent AdDNS6K microinjection where the injections missed the Arc did not differ from control rats treated with AdGFP (Figure 3I). Moreover, bilateral microinjection of AdDNS6K into the ventromedial hypothalamus, which is adjacent to the Arc, failed to alter the renal SNA response evoked by leptin (Figure S2G). Together, these results implicate mTORC1 in the Arc as a key downstream pathway in the control of renal SNA and arterial pressure by leptin.

PI3K Links the Leptin Receptor to mTORC1 Signaling

To gain insight into the mechanisms mediating leptin receptor activation of mTORC1 signaling, we investigated the role of the PI3K, which is a critical upstream element in the intracellular cascade regulating mTORC1 signaling (Hay and Sonenberg, 2004; Wang et al., 2006). Leptin stimulates hypothalamic PI3K (Niswender et al., 2001; Rahmouni et al., 2008); and inhibition of PI3K signaling blocks the renal SNA response to leptin (Rahmouni et al., 2003a; Rahmouni et al., 2008). Therefore, we postulated that PI3K signaling links the leptin receptor to mTORC1 in the control of renal SNA and arterial pressure. To test this, we first evaluated the effect of pharmacological blockade of PI3K (using LY29004 or Wortmannin) on leptin-induced stimulation of mTORC1 signaling. Leptin activation of S6 was blocked by LY29004 and Wortmannin in hypothalamic GT1-7 cells that were transfected with ObRb, the long-signaling form of the leptin receptor (Figure 4A–B). Knock-down of the catalytic p110α subunit of PI3K (Figure S3A) also inhibited leptin activation of S6 in GT1-7 cells (Figure 4C). Moreover, pre-treatment with LY29004 abolished the ability of ICV leptin to increase hypothalamic p-S6K and p-S6 in mice (Figure 4D and data not shown).

Figure 4. PI3K mediates leptin-induced mTORC1 activation, sympathoexcitation, and arterial pressure increase.

(A–C) Western blot analysis of the effect of PI3K blockade (A: LY294002, B: Wortmannin and C: knock-down of p110α subunit with siRNA) on leptin–induced increase in p-S6 (Ser240/244) in hypothalamic GT1-7 cells transfected with the leptin receptor (ObRb, n=4 each).

(D) Effect of PI3K inhibition (ICV LY294002, 0.1 μg) on ICV leptin (2 μg)–induced increase in p-S6 (Ser240/244) in the mediobasal hypothalamus of C57BL/6J mice (n=4 each).

(E–F) Comparison of p-S6 (Ser240/244) levels in the Arc of wild type (WT), PtenΔObRb and p110αD933A/WT mice that were treated with vehicle or leptin (60 μg, IP) (n=3 each). (G–I) Renal SNA response (G: time-course; H and I: average of last hour) to ICV vehicle, leptin (2 μg) or MTII (100 pM) in WT, PtenΔObRb, and p110αD933A/WT mice (n=3–17).

(J–K) Comparison of baseline radiotelemetric MAP (J: hourly averages over 24 h, K: 24 h averages) between WT, PtenΔObRb, and p110αD933A/WT mice (n=4–8).

(L) MAP response to leptin (60 μg, IP) in WT, PtenΔObRb, and p110αD933A/WT mice (n=4–8).

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 vs. vehicle controls, †P<0.05 vs. WT mice.

To study further the role of PI3K in mediating mTORC1 activation by leptin we used two contrasting mouse models with either abolished or enhanced effect of leptin on PI3K: the leptin-resistant p110αD933A/WT mice, which carry a knock-in mutation that abrogates p110α kinase activity (Foukas et al., 2006), and the leptin-sensitive PtenΔObRb mice, which have the lipid phosphatase Pten (phosphatase and tensin homolog) ablated in cells expressing the ObRb, leading to enhanced PI3K pathway specifically in leptin-sensitive neurons (Plum et al., 2007). To avoid differences in body weight as a variable, we used mutant mice with body weights matching the littermate controls (Figure S3B–C). Notably, the PtenΔObRb mice had elevated p-S6 staining in the Arc, at baseline and in response to leptin, as detected by immunohistochemistry (Figure 4E–F). Conversely, the p110αD933A/WT mice had reduced p-S6 immunoreactivity in the Arc, both at baseline and in response to leptin (Figure 4E–F). In line with a recent report (Dagon et al., 2012), these data implicate PI3K as a mediator underlying leptin receptor activation of mTORC1 signaling. It should be noted, however, that both Pten and p110α are major regulators of mTORC1 activity. Thus, the altered baseline mTORC1 activity in the Arc of PtenΔObRb mice and p110αD933A/WT mice may be expected. Additional experiments are needed to determine the contribution of leptin to the changes in baseline mTORC1 activity in the Arc of the two mouse models.

PI3K Activity Is Crucial for the Sympathetic and Cardiovascular Effects of Leptin

Lastly, we assessed the sympathetic and cardiovascular ramifications of the contrasting change in the activity of the PI3K-mTORC1 axis. Relative to control mice, the PtenΔObRb mice had a strikingly enhanced renal SNA response to ICV leptin while the p110αD933A/WT mice displayed a blunted response (Figure 4G–H). In contrast, MTII–induced renal SNA increase was similar in PtenΔObRb, p110αD933A/WT, and control mice (Figure 4I), arguing for the specificity of the altered renal SNA responses to leptin. The lack of arterial pressure response to ICV leptin in anesthetized mice (Harlan et al., 2011b) prompted us to use radiotelemetry to assess the hemodynamic consequences of the bidirectional change in PI3K-mTORC1 activity. Interestingly, baseline arterial pressure was elevated in PtenΔObRb mice as compared to controls, whereas the p110αD933A/WT mice had normal baseline arterial pressure (Figure 4J–K). However, alteration of PI3K signaling in mice did not alter heart rate (Figure S3D–E). Finally, we examined the effect of leptin on arterial pressure in the two mouse models. Leptin-induced arterial pressure increase was enhanced in PtenΔObRb mice, but blunted in p110αD933A/WTmice (Figure 4L). In PtenΔObRb mice, leptin also attenuated the arterial pressure decrease caused by fasting (Figure S3F). Together, these findings demonstrate the importance of PI3K pathway for the sympathetic and hemodynamic regulation by leptin.

This study identifies a role for hypothalamic mTORC1 in the regulation of sympathetic nerve traffic and arterial pressure. Our data also indicate the importance of PI3K-mTORC1 signaling in mediating the sympathetic and hemodynamic effects of leptin. Our findings broaden the role of hypothalamic mTORC1 signaling, which has previously been implicated in the control of other physiological processes such as feeding (Blouet et al., 2008; Cota et al., 2006), glucose metabolism (Ono et al., 2008) and reproductive function (Roa et al., 2009). The ability of mTORC1 to sense and integrate various signals, combined with its prominent role in the control of a plethora of cellular processes ranging from gene transcription to neuronal excitability, raises the possibility that mTORC1 may serve as a “molecular hub” that allow hypothalamic neurons to integrate various inputs including hormones and nutrients to produce coordinated responses that maintain homeostasis with potential pathophysiological consequences. Indeed, hyperactive hypothalamic mTORC1 signaling has recently been implicated in age-related obesity (Yang et al., 2012). Moreover, inhibition of mTORC1 signaling (with rapamycin treatment or deletion of s6k1 gene) extends lifespan in mice (Harrison et al., 2009; Selman et al., 2009). It will be interesting to examine whether hypothalamic mTORC1 activation may account for the sympathetic overdrive, hypertension and deteriorating cardiovascular health that are commonly associated with aging (Seals and Dinenno, 2004; North and Sinclair, 2012).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

All animal protocols were approved by the University of Iowa Animal Research Committee. Details about the strains of rats and mice used are provided in the Supplemental Information.

Hypothalamic mTORC1 signaling

Animals were fasted for 3 hours before ICV injections. Animals were killed at the indicated time points by CO2 asphyxiation. The mediobasal hypothalamus was quickly removed from each animal. The total proteins were extracted using lysis buffer and processed for Western Blotting.

Sympathetic Nerve Recording

Renal SNA was assessed using multifiber recording. Briefly, anesthesia was induced with intraperitoneal injection of Ketamine (91 mg/kg) and Xylazine (9.1 mg/kg) cocktail and sustained with intravenous administration of α-chloralose (6 mg/kg/h). The renal nerve was identified, mounted on bipolar platinum-iridium electrodes, and the ensemble fixed with silicone gel. Background noise was excluded in the assessment of renal SNA by correcting for post-mortem activity.

Regional Blood Flows

Rats were anesthetized with Ketamine/Xylazine cocktail, intraperitoneally. After careful dissection and separation of each artery, individual ultrasound Doppler probes were placed around the left renal artery (0.8 mm diameter), superior mesenteric artery (1.0 mm), left iliac artery (1.0 mm), and the lower abdominal aorta (1.3 mm). Once a clear Doppler echo signal was achieved, each probe was securely tied into place and wires tunneled subcutaneously out of the nape of the animal’s neck.

Data Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM and analyzed using one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with or without repeated measure. When analysis of ANOVA reached significance, appropriate post hoc tests were used. A value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Activation of mTORC1 signaling in the hypothalamus with leucine increase sympathetic traffic and arterial pressure

Blockade of hypothalamic mTORC1 with rapamycin blocks the leucine-induced increase in sympathetic traffic and arterial pressure

mTORC1 in the arcuate nucleus is critically involved in relying the control of sympathetic traffic and arterial pressure by leptin

PI3K pathway underlies leptin receptor activation of hypothalamic mTORC1 signaling and arterial pressure regulation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Pamela Mellon for the GT1-7 cell line, Gary Schwartz for providing the AdDNS6K (and The University of Iowa Gene Transfer Vector Core for its amplification), Jens Brüning for the PtenΔObRb mice and Bart Vanhaesebroeck for p110αD933A/WT mice. We thank Martin Cassell for assistance with the neuroanatomical aspects of the studies and Allyn Mark and Paul Casella for the helpful comments on the manuscript. This study was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (HL084207 and HL014388), American Diabetes Association (1-11-BS-127) and the University of Iowa Fraternal Order of Eagles Diabetes Center. SMH was supported by Postdoctoral Fellowship Award from The American Heart Association (12POST9410009).

Footnotes

Disclosures/conflicts of interest: None.

Supplemental Information includes three Figures, Extended Experimental Procedures, and Supplemental References and can be found with this article online.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Avruch J, Long X, Ortiz-Vega S, Rapley J, Papageorgiou A, Dai N. Amino acid regulation of TOR complex 1. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E592–602. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90645.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouet C, Ono H, Schwartz GJ. Mediobasal hypothalamic p70 S6 kinase 1 modulates the control of energy homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2008;8:459–467. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouet C, Jo YH, Li X, Schwartz GJ. Mediobasal hypothalamic leucine sensing regulates food intake through activation of a hypothalamus-brainstem circuit. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8302–8311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1668-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bove J, Martinez-Vicente M, Vila M. Fighting neurodegeneration with rapamycin: mechanistic insights. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:437–452. doi: 10.1038/nrn3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota D, Proulx K, Smith KA, Kozma SC, Thomas G, Woods SC, Seeley RJ. Hypothalamic mTOR signaling regulates food intake. Science. 2006;312:927–930. doi: 10.1126/science.1124147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagon Y, Hur E, Zheng B, Wellenstein K, Cantley LC, Kahn BB. p70S6 kinase phosphorylates AMPK on serine 491 to mediate leptin’s effect on food intake. Cell Metab. 2012;16:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampney RA, Horiuchi J, Killinger S, Sheriff MJ, Tan PS, McDowall LM. Long-term regulation of arterial blood pressure by hypothalamic nuclei: some critical questions. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2005;32:419–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2005.04205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foukas LC, Claret M, Pearce W, Okkenhaug K, Meek S, Peskett E, Sancho S, Smith AJ, Withers DJ, Vanhaesebroeck B. Critical role for the p110alpha phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase in growth and metabolic regulation. Nature. 2006;441:366–370. doi: 10.1038/nature04694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet PG. The sympathetic control of blood pressure. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:335–346. doi: 10.1038/nrn1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JE, da Silva AA, do Carmo JM, Dubinion J, Hamza S, Munusamy S, Smith G, Stec DE. Obesity-induced hypertension: role of sympathetic nervous system, leptin, and melanocortins. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:17271–17276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.113175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JM, Jeong SJ, Park MC, Kim G, Kwon NH, Kim HK, Ha SH, Ryu SH, Kim S. Leucyl-tRNA synthetase is an intracellular leucine sensor for the mTORC1-signaling pathway. Cell. 2012;149:410–424. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlan SM, Morgan DA, Agassandian K, Guo DF, Cassell MD, Sigmund CD, Mark AL, Rahmouni K. Ablation of the Leptin Receptor in the Hypothalamic Arcuate Nucleus Abrogates Leptin-Induced Sympathetic Activation. Circ Res. 2011a;108:808–812. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.240226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlan SM, Morgan DA, Dellsperger DJ, Myers MG, Jr, Mark AL, Rahmouni K. Cardiovascular and sympathetic effects of disrupting tyrosine 985 of the leptin receptor. Hypertension. 2011b;57:627–632. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.166538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DE, Strong R, Sharp ZD, Nelson JF, Astle CM, Flurkey K, Nadon NL, Wilkinson JE, Frenkel K, Carter CS, et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature. 2009;460:392–395. doi: 10.1038/nature08221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay N, Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1926–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski J, Sheng M. The growing role of mTOR in neuronal development and plasticity. Mol Neurobiol. 2006;34:205–219. doi: 10.1385/MN:34:3:205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamane Y, Petroulakis E, LeBacquer O, Sonenberg N. mTOR, translation initiation and cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25:6416–6422. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison CD, Xi X, White CL, Ye J, Martin RJ. Amino acids inhibit Agrp gene expression via an mTOR-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E165–E171. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00675.2006.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Bhatt S, Sapru HN. Cardiovascular responses to hypothalamic arcuate nucleus stimulation in the rat: role of sympathetic and vagal efferents. Hypertension. 2009;54:1369–1375. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newgard CB, An J, Bain JR, Muehlbauer MJ, Stevens RD, Lien LF, Haqq AM, Shah SH, Arlotto M, Slentz CA, et al. A branched-chain amino acid-related metabolic signature that differentiates obese and lean humans and contributes to insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2009;9:311–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niswender KD, Morton GJ, Stearns WH, Rhodes CJ, Myers MG, Jr, Schwartz MW. Intracellular signalling. Key enzyme in leptin-induced anorexia. Nature. 2001;413:794–795. doi: 10.1038/35101657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North BJ, Sinclair DA. The intersection between aging and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2012;110:1097–1108. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.246876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono H, Pocai A, Wang Y, Sakoda H, Asano T, Backer JM, Schwartz GJ, Rossetti L. Activation of hypothalamic S6 kinase mediates diet-induced hepatic insulin resistance in rats. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2959–2968. doi: 10.1172/JCI34277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plum L, Rother E, Munzberg H, Wunderlich FT, Morgan DA, Hampel B, Shanabrough M, Janoschek R, Konner AC, Alber J, et al. Enhanced leptin-stimulated Pi3k activation in the CNS promotes white adipose tissue transdifferentiation. Cell Metab. 2007;6:431–445. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmouni K, Haynes WG, Morgan DA, Mark AL. Intracellular mechanisms involved in leptin regulation of sympathetic outflow. Hypertension. 2003a;41:763–767. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000048342.54392.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmouni K, Haynes WG, Morgan DA, Mark AL. Role of melanocortin-4 receptors in mediating renal sympathoactivation to leptin and insulin. J Neurosci. 2003b;23:5998–6004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-14-05998.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmouni K, Morgan DA. Hypothalamic arcuate nucleus mediates the sympathetic and arterial pressure responses to leptin. Hypertension. 2007;49:647–652. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000254827.59792.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmouni K, Sigmund CD, Haynes WG, Mark AL. Hypothalamic ERK Mediates the Anorectic and Thermogenic Sympathetic Effects of Leptin. Diabetes. 2008;58:536–542. doi: 10.2337/db08-0822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roa J, Garcia-Galiano D, Varela L, Sanchez-Garrido MA, Pineda R, Castellano JM, Ruiz-Pino F, Romero M, Aguilar E, Lopez M, et al. The mammalian target of rapamycin as novel central regulator of puberty onset via modulation of hypothalamic Kiss1 system. Endocrinology. 2009;150:5016–5026. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seals DR, Dinenno FA. Collateral damage: cardiovascular consequences of chronic sympathetic activation with human aging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1895–905. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00486.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selman C, Tullet JM, Wieser D, Irvine E, Lingard SJ, Choudhury AI, Claret M, Al-Qassab H, Carmignac D, Ramadani F, et al. Ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 signaling regulates mammalian life span. Science. 2009;326:140–144. doi: 10.1126/science.1177221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah SH, Bain JR, Muehlbauer MJ, Stevens RD, Crosslin DR, Haynes C, Dungan J, Newby LK, Hauser ER, Ginsburg GS, Newgard CB, Kraus WE. Association of a peripheral blood metabolic profile with coronary artery disease and risk of subsequent cardiovascular events. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:207–214. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.852814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah SH, Sun JL, Stevens RD, Bain JR, Muehlbauer MJ, Pieper KS, Haynes C, Hauser ER, Kraus WE, Granger CB, et al. Baseline metabolomic profiles predict cardiovascular events in patients at risk for coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2012;163:844–850.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiech L, Perycz M, Malik A, Jaworski J. Role of mTOR in physiology and pathology of the nervous system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:116–132. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Rhodes CJ, Lawrence JC., Jr Activation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) by insulin is associated with stimulation of 4EBP1 binding to dimeric mTOR complex 1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24293–24303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603566200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 2006;124:471–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SB, Tien AC, Boddupalli G, Xu AW, Jan YN, Jan LY. Rapamycin Ameliorates Age-Dependent Obesity Associated with Increased mTOR Signaling in Hypothalamic POMC Neurons. Neuron. 2012;75:425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.