INTRODUCTION

Ultraviolet radiation (UVR), specifically in the spectrum of ultraviolet (UV) A (wavelength 320–400 nm) and B (wavelength 290–320 nm) light, is a well-documented trigger of skin lesions in patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE).1, 2 Thus, patients are counseled to avoid direct sun exposure and use photoprotection whenever outdoors. Five of the most common photoprotective methods are applying sunscreen, wearing long-sleeved clothing, hats, and sunglasses, and seeking shade.3, 4

Studies on the photoprotective habits of lupus patients have mainly focused only on their frequency of sunscreen usage. A study of 60 Puerto Rican patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) showed that while 98.3% reported knowing that sunlight can exacerbate cutaneous manifestations of their disease, only 50% actually practiced regular sunscreen use.5 66.7% of SLE patients in Brazil (N=159) reported year-round sunscreen use, compared with only 23.1% of CLE patients in Ireland (N=52), where the annual UV exposure is lower.6, 7 Whether CLE patients compensate by adopting other photoprotective habits is unknown.

By means of a cross-sectional survey distributed to patients enrolled in the University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) CLE Registry, we sought to assess their overall photoprotection and frequency of individual photoprotective methods (e.g. wearing sunscreen, hat, long sleeves, sunglasses, staying under shade or umbrella). We also subdivided this CLE population by various demographic and clinical characteristics of interest. Our primary aim was to identify subgroups of CLE patients who are least likely to engage in overall photoprotection and individual photoprotective habits.

METHODS

Patient population

A cross-sectional survey to evaluate photoprotective practices was administered to CLE patients enrolled in the CLE Registry at University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) Medical Center in Dallas, TX, (IRB protocols #1120008-008 (date approved: 6/21/10), #082010-241 (date approved: 10/28/10), Principal Investigator: Benjamin F. Chong) from June of 2010 to April of 2012. Patients were eligible for inclusion upon completion of a questionnaire on their photoprotective habits. Patients who did not complete the photoprotective habits questionnaire, or who had a diagnosis of another autoimmune disease other than CLE, were excluded. Additional information regarding patient demographics, Fitzpatrick skin type, disease duration, CLE subtype, number of American College of Rheumatology SLE diagnostic criteria, presence or absence of SLE, number of oral lupus medications, hours spent in the sun per week, occupational setting (outdoors vs. indoors), history of photosensitivity, and history of smoking were collected. Cutaneous and systemic disease activities were assessed using the Cutaneous Lupus Activity and Severity Index (CLASI)8 and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI), respectively.9 All patients were 18 years or older, and were enrolled after signing institution review board-approved consent forms.

Photoprotective habits survey

The survey consisted of questions on frequency of usage for each of five different photoprotective methods (e.g., applying sunscreen, wearing hats, long-sleeved shirts, and sunglasses, and staying under shade or umbrella). Frequency of usage for each method was assessed using a 4-point Likert scale, where 1=rarely, 2=sometimes, 3=often, and 4=always. Overall sun protection habits (SPH) scores were calculated for each patient by taking the numerical average of these responses. The range of possible SPH scores was thus 1–4, where a higher score implied greater adherence to photoprotective practices. SPH scores have been previously validated in earlier studies on normal patients.10, 11

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics with frequency counts and percentages. Comparisons between groups on frequencies of photoprotective method use were performed using Fisher’s exact tests for r x c contingency tables. Comparisons between average Likert scores for patient subgroups were performed using Kruskal-Wallis tests (multiple groups) or Mann-Whitney U tests (two groups). p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

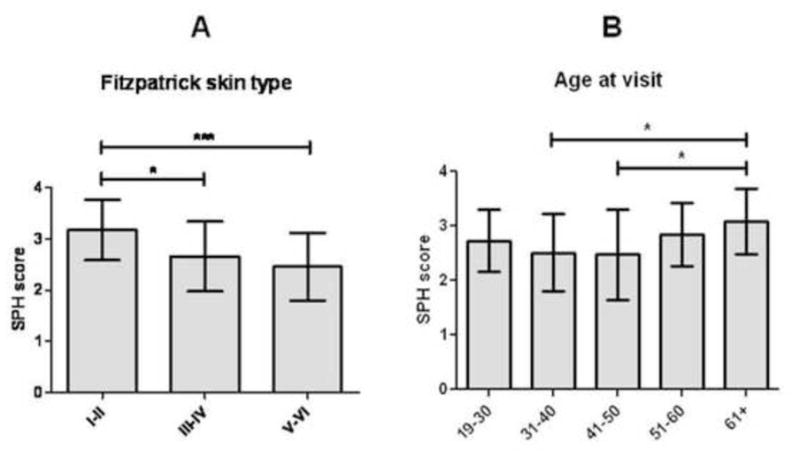

CLE SPH scores

To assess general practices of photoprotection, we first focused on the overall SPH scores of our CLE population (N=105). The average SPH score was 2.7±0.7. We compared SPH scores in CLE patients subdivided by variables of interest in Table I. Significant differences were found between the average SPH scores of CLE patients when categorized by their skin type (p=0.001). Specifically, the SPH scores of CLE patients with skin types I–II (3.2±0.6) were significantly higher than the scores of patients with skin types III–IV (2.7±0.7, p=0.01) and skin types V–VI (2.5±0.7; p<0.001) (Fig 1, A). There were also significant differences between groups categorized by age at visit (p=0.04), with the SPH scores of the 61 and older age group (3.1±0.6) significantly higher than those of the 31–40 (2.5±0.7; p=0.01) and the 41–50 (2.5±0.8; p=0.02) age groups (Fig 1, B). No significant differences or correlation in SPH scores were present in CLE patient subgroups categorized by the other variables listed in Table I (data not shown).

Table I.

CLE patient characteristics (N=105)

| Gender (N, %) | |

| Male | 15 (14.3%) |

| Female | 90 (85.7%) |

| Age at visit (years) (Avg±SD) | 45.7±13.2 |

| 19–30 years (N, %) | 14 (13.3%) |

| 31–40 years | 25 (23.8%) |

| 41–50 years | 28 (26.7%) |

| 51–60 years | 24 (22.9%) |

| 61+ years | 14 (13.3%) |

| Ethnicity (N, %) | |

| African-American | 54 (51.4%) |

| Caucasian | 37 (35.2%) |

| Hispanic | 8 (7.6%) |

| Asian | 4 (3.8%) |

| Mixed | 2 (1.9%) |

| Educational level* (N, %) | |

| High school or less | 43 (48.3%) |

| College or equivalent | 36 (40.4%) |

| Graduate school or higher | 10 (11.2%) |

| Income (yearly)* (N, %) | |

| Less than $10,000 | 37 (37.4%) |

| $10,000 – $50,000 | 37 (37.4%) |

| $50,000 – $100,000 | 19 (19.2%) |

| More than $100,000 | 6 (6.1%) |

| Fitzpatrick skin type* (N, %) | |

| I–II | 22 (22.2%) |

| III–IV | 33 (33.3%) |

| V–VI | 44 (44.4%) |

| Season of visit (N,%) | |

| Spring | 21 (20.0%) |

| Summer | 36 (34.3%) |

| Fall | 23 (21.9%) |

| Winter | 25 (23.8%) |

| Disease duration (years)* (Avg±SD) | 8.1±8.2 |

| CLE subtype* (N, %) | |

| ACLE | 11 (10.6%) |

| SCLE | 18 (17.3%) |

| DLE | 70 (67.3%) |

| Chilblains lupus | 3 (2.9%) |

| Tumid lupus | 2 (1.9%) |

| Number of SLE criteria met (Avg±SD) | 4.5±2.1 |

| SLE diagnosis? (N, %) | |

| Yes | 63 (60.0%) |

| No | 42 (40.0%) |

| CLASI activity score (Avg±SD) | 5.2±5.4 |

| CLASI damage score (Avg±SD) | 6.7±6.9 |

| SLEDAI score (Avg±SD) | 1.9±2.5 |

| Number of oral lupus medications (Avg±SD) | 1.3±1.1 |

| Time spent in sun (hrs/wk)* (N, %) | |

| <2 | 53 (53.0%) |

| 2–4 | 23 (23.0%) |

| 4–6 | 6 (6.0%) |

| >6 | 18 (18.0%) |

| Work outdoors for occupation?* (N, %) | |

| Yes | 12 (12.1%) |

| No | 87 (87.9%) |

| History of photosensitivity (N, %) | |

| Yes | 87 (82.9%) |

| No | 18 (17.1%) |

| History of smoking* (N, %) | |

| Never | 52 (50.0%) |

| Past | 16 (15.4%) |

| Current | 36 (34.6%) |

Information on specific patient characteristics were not available for the following: education (16 unavailable), income (6 unavailable), Fitzpatrick skin type (6 unavailable), disease duration (2 unavailable), CLE subtype (1 unavailable), time spent in sun (5 unavailable), work outdoors (6 unavailable), and history of smoking (1 unavailable).

Abbreviations: ACLE = acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus; CLE = cutaneous lupus erythematosus; DLE = discoid lupus erythematosus; SCLE = subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus; SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus

Fig 1.

SPH scores in CLE patients subgrouped by Fitzpatrick skin type and by age at visit. (A–B) Means and standard deviations (SDs) were calculated for SPH scores for CLE patients with skin types I–II (N=22), III–IV (N=33), and V–VI (N=44) (A); and ages at visit of 19–30 (N=14), 31–40 (N=25), 41–50 (N=28), 51–60 (N=24), and 61+ years of age (N=14) (B). SPH scores were calculated as the numerical average of CLE patients’ frequency of usage of five different photoprotective methods (e.g., applying sunscreen, wearing hats, long-sleeved shirts, and sunglasses, and staying under shade/umbrella), where frequency of usage of each method was assessed using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, and 4 = always). Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests were performed to determine statistical significance. *: p≤0.05, ***: p<0.001

Usage frequencies for each photoprotective method in CLE patients

We then assessed frequencies of usage for each individual photoprotective method for the overall CLE population. Seeking shade or umbrella, using sunscreen, and wearing sunglasses were most popular with CLE patients, with 68.6%, 59.0%, and 56.2% responding that they “often” or “always” use those methods, respectively. Long sleeves and hats were less popular, with 49.5% and 44.8% of patients responding that they “often” or “always” wear hats or long sleeves, respectively (Table II).

Table II.

Usage frequencies for each photoprotective methods in CLE patients (N=105)

| Rarely/Sometimes (%) | Often/Always (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Shade/umbrella | 31.4 | 68.6 |

| Sunscreen | 41.0 | 59.0 |

| Sunglasses | 43.8 | 56.2 |

| Long sleeves | 50.5 | 49.5 |

| Hat | 55.2 | 44.8 |

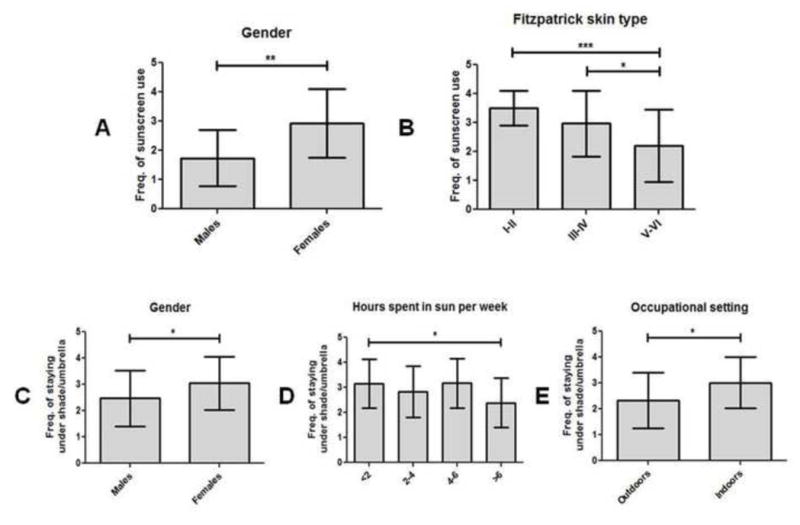

Sunscreen and shade/umbrella use in CLE patients

For each individual photoprotective method, we also compared frequency of usage by CLE subgroups based on their Likert scores. Male CLE patients (1.7±1.0) were significantly less likely to use sunscreen than females (2.9±1.2; p=0.001) (Fig 2, A). CLE patients with skin types V–VI (2.2±1.3) used sunscreen significantly less frequently than patients with skin types I–II (3.5±0.6; p<0.001) and III–IV (3.0±1.1; p=0.01) (p<0.001) (Fig 2, B).

Fig 2.

Frequency of sunscreen and shade/umbrella usage in CLE patients subgrouped by demographics and social characteristics. (A–B), Means and SDs were calculated for frequencies of sunscreen usage by CLE patients of male (N=15) and female (N=90) genders (A); and skin types I–II (N=22), III–IV (N=33), and V–VI (N=44) (B). (C–E), Means and SDs were calculated for frequencies of shade/umbrella usage by CLE patients of male (N=15) and female (N=90) genders (C); spending less than 2 (N=53), 2–4 (N=23), 4–6 (N=6), and greater than 6 (N=18) hours per week in the sun (D); and who work outdoors (N=12) and indoors (N=87) (E). Frequencies of sunscreen and shade/umbrella usage were assessed using a 4-point Likert scale (1=rarely, 2=sometimes, 3=often, and 4=always). Kruskal-Wallis tests and Mann-Whitney U tests were performed to determine statistical significance. *: p≤0.05, **: p≤0.005, ***: p≤0.001

Male CLE patients (2.5±1.1) were significantly less likely to stay under shade or umbrella than females (3.0±1.0) (p=0.04) (Fig 2, C). Time spent in the sun was another variable for which there were significant differences in shade/umbrella use between groups (p=0.04). CLE patients who spent more than 6 hours in the sun per week (2.4±1.0) stayed under shade or umbrella significantly less often than CLE patients who spent less than 2 hours in the sun per week (3.2±1.0; p=0.01) (Fig 2, D). CLE patients who worked outdoors for their occupation also had a lower frequency of shade/umbrella use (2.3±1.1) than those who worked indoors (3.0±1.0; p=0.04) (Fig 2, E).

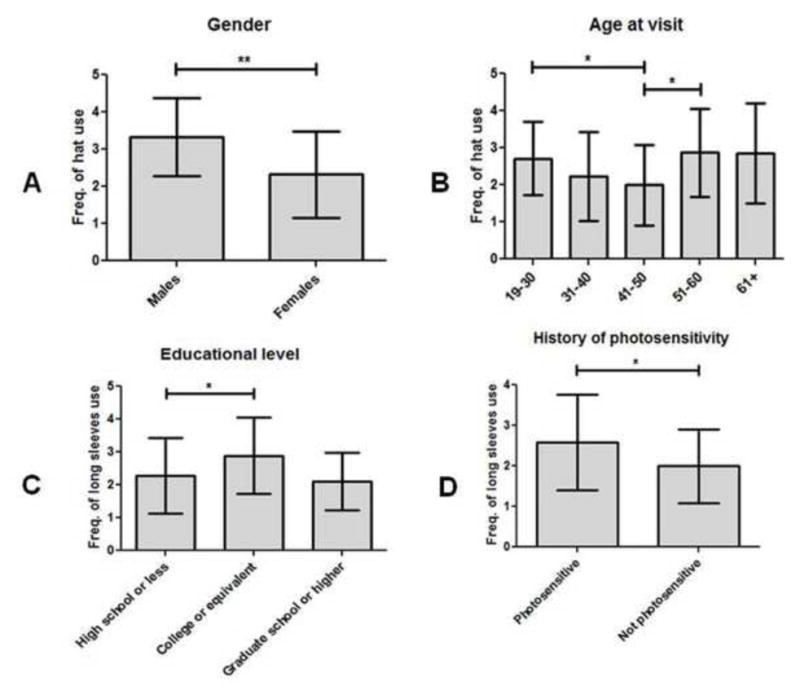

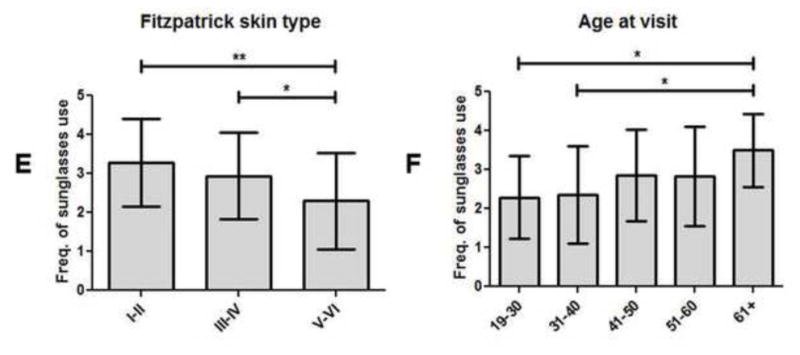

Hat, long sleeves, and sunglasses use in CLE patients

Gender differences were also evident in the frequency of hat use by this CLE population. Female CLE patients (2.3±1.2) were significantly less likely to wear hats than males (3.3±1.0) (p=0.003) (Fig 3, A). There were also significant differences in hat use between CLE groups categorized by age at visit (p=0.05). The 41–50 age group (2.0±1.1) had significant lower frequencies of hat use than both the 19–30 age group (2.7±1.0; p=0.04) and the 51–60 age group (2.9±1.2; p=0.01) (Fig 3, B).

Fig 3.

Frequency of hat, long sleeves, and sunglasses usage in CLE patients subgrouped by demographics and history of photosensitivity. (A–B), Means and SDs were calculated for frequency of hat usage in CLE patients of male (N=15) and female (N=90) genders (A); and ages at visit of 19–30 (N=14), 31–40 (N=25), 41–50 (N=28), 51–60 (N=24), and 61+ years of age (N=14) (B). (C–D), Means and SDs were calculated for frequency of long sleeve usage in CLE patients with educational levels of high school or less (N=43), college or equivalent (N=36), and graduate school or higher (N=10) (C); and with and without a history of photosensitivity (N=87 and N=18, respectively) (D). (E–F), Means and SDs were calculated for frequency of sunglasses usage in CLE patients with skin types I–II (N=22), III–IV (N=33), and V–VI (N=44) (E); and ages at visit of 19–30 (N=14), 31–40 (N=25), 41–50 (N=28), 51–60 (N=24), and 61+ (N=14) (F). Frequencies of hat, long sleeves, and sunglasses usage were assessed using a 4-point Likert scale (1=rarely, 2=sometimes, 3=often, and 4=always). Kruskal-Wallis tests and Mann-Whitney U tests were performed to determine statistical significance. *: p≤0.05, **: p≤0.005

Frequency of long-sleeved shirt use differed significantly between CLE patients of different educational levels (p=0.04). Specifically, CLE patients with a high school or lower education wore long-sleeved shirts significantly less often (2.3±1.1) than CLE patients with a college degree or equivalent (2.9±1.2; p=0.03) (Fig 3, C). CLE patients without a history of photosensitivity also had a lower frequency of long-sleeved shirt use (2.0±0.9) than CLE patients who were not photosensitive (2.6±1.2; p=0.05) (Fig 3, D).

Frequency of sunglasses use differed significantly between CLE patients of different skin types (p=0.01). CLE patients with skin types V–VI wore sunglasses significantly less frequently (2.3±1.2) than CLE patients with skin types I–II (3.3±1.1; p=0.003) and III–IV (2.9±1.1; p=0.02) (Fig 3, E). There was also a significant difference in frequency of sunglasses use between CLE patients based on age at visit (p=0.04). CLE patients ages 19–30 (2.3±1.1; p=0.01) and ages 31–40 (2.4±1.3; p=0.01) reported significantly lower frequencies of sunglasses use than CLE patients ages 61 and higher (3.5±0.9) (Fig 3, F). The variables that lacked significance for all of the photoprotective methods were income, disease duration, CLE subtype, number of SLE criteria met, history of SLE, number of oral lupus medications, and history of smoking (Supplementary Table I).

DISCUSSION

In studies using healthy or skin cancer patients, skin type, age, and gender had been identified as demographic indicators for deficient photoprotective habits.12–15 These studies generally found that individuals with dark skin types practiced photoprotection less frequently than those with light skin.13 In our CLE population, overall SPH scores were significantly lower for the medium-skinned (i.e. skin types III–IV) and dark-skinned (i.e. skin types V–VI) CLE patients than for the light-skinned CLE patients (i.e. skin types I–II). Sunscreen and sunglasses use were significantly lower in CLE patients with skin types V–VI compared with others. The tendency of CLE patients with skin types V–VI to neglect photoprotection in comparison with patients with light skin has been well-established by prior studies on non-CLE populations.12, 14, 16 One possible explanation for this discrepancy may be attributed to dark-skinned patients having lower incidences of sunburn and skin cancer than light-skinned patients,17, 18 creating a false misconception among dark-skinned patients that they are protected against the damaging effects of UVR. This finding is particularly noteworthy because, in contrast to skin cancer, the incidence of lupus erythematosus is disproportionately high among dark-skinned individuals.19

Age at visit was another important indicator of CLE patients’ photoprotective habits. Patients aged 31–40 and patients aged 41–50 had significantly lower SPH scores than the oldest group aged 61 or older. Patients aged 41–50 were found to wear hats significantly less than patients aged 19–30 and patients aged 51–60. The 31–40 year old patient group wore sunglasses significantly less than the 61 or older age group. Despite trends in periodically administered national health surveys showing that younger patients were less likely to report practicing one or more photoprotective behaviors,15 we found a greater awareness of the importance of photoprotection in the youngest and oldest age groups versus those between ages 31 and 50. Furthermore, the 31–50 year old age group overlaps with the most common age range for onset of lupus erythematosus (LE), which is between 20 to 40 years of age,20 and highlights their need for photoprotection education.

Wearing sunscreen and staying under shade or umbrella were two specific methods for which CLE males lagged significantly behind CLE females, although CLE males were found to wear hats for photoprotection more frequently than did CLE females.13, 15 The gender difference in photoprotective habits may be attributed to cultural customs. However, the photoprotective methods favored by men may not be as effective as those methods favored by women. These gender-based disparities in individual photoprotection habits were identical to those shown in normal and skin cancer patients. These findings imply that gender-specific disparities in the use of specific methods of photoprotection may be universal amongst healthy and skin cancer patients, and patients with photosensitive diseases.

As reported by the 2008 National Health Interview Survey, wearing long sleeves was one of the least popular photoprotective methods among adults, and more convenient practices such as sunscreen and shade/umbrella use were the two most popular methods.15 Our findings mirrored these national trends. Notably, wearing long sleeves were the only photoprotective method for which photosensitive CLE patients had a significantly higher frequency of use than non-photosensitive CLE patients. This could be due to a deliberate effort by photosensitive CLE patients’ to use “extra” photoprotective methods that others might perceive as inconvenient or unnecessary, such as wearing long sleeves in hot summer weather.

Limitations of this study include its reporter bias, in which patients may over-estimate their usage of photoprotection to satisfy their providers’ expectations. Additionally, the study population was limited to patients in one geographic location. We did not also seek to identify barriers to photoprotection or knowledge of importance of photoprotection in our CLE patients. As our results on sunscreen use were of special interest, we are conducting future studies to determine sunscreen usage habits in a greater number of CLE patients, assess knowledge of sunscreen use, and identify potential barriers to regular sunscreen usage faced by our CLE population.

In conclusion, we have identified several CLE patient subgroups that are significantly deficient in their usage of photoprotection, compared with the rest of the CLE population. Patients between the ages of 31–50 and patients with medium and dark Fitzpatrick skin types had significantly low overall SPH scores. Males, patients with dark Fitzpatrick skin types, and patients between the ages of 31–50 were deficient in more than one of the five photoprotective methods studied. Moving forward, identification of these subgroups will assist clinicians in targeting specific CLE patients in greatest need of education regarding photoprotection.

Supplementary Material

p-values* for demographic and clinical variables versus overall SPH scores and individual photoprotective methods

CAPSULE SUMMARY.

Sunscreen use in cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) patients is deficient.

CLE males, dark-skinned patients, and patients aged 31-50 are least likely to practice photoprotection.

Education regarding the importance of photoprotection should be greatly emphasized in these subgroups of CLE patients.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Rebecca Vasquez, Andrew Kim, Sandra Victor, and Julie Song for their assistance in the compilation of patient data.

Grant Support: The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23AR061441. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- ACLE

acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

- CLASI

Cutaneous Lupus Activity and Severity Index

- CLE

cutaneous lupus erythematosus

- DLE

discoid lupus erythematosus

- NHIS

National Health Interview Survey

- SCLE

subacute cutaneous lupus

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- SLEDAI

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index

- SPH

sun protection habits

- UTSW

University of Texas Southwestern

- UVA

ultraviolet A

- UVB

ultraviolet B

- UVR

ultraviolet radiation

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Dr. Chong is an investigator for Celgene Corporation, Amgen Incorporated, and Daavlin Corporation. Dr. Bernstein serves as a consultant for Johnson and Johnson.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lehmann P, Holzle E, Kind P, Goerz G, Plewig G. Experimental reproduction of skin lesions in lupus erythematosus by UVA and UVB radiation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:181–7. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70020-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuhn A, Sonntag M, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, Megahed M, Ruzicka T, et al. Phototesting in lupus erythematosus: a 15-year experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:86–95. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.114589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuhn A, Ruland V, Bonsmann G. Photosensitivity, phototesting, and photoprotection in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2010;19:1036–46. doi: 10.1177/0961203310370344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothfield N, Sontheimer RD, Bernstein M. Lupus erythematosus: systemic and cutaneous manifestations. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:348–62. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vila LM, Mayor AM, Valentin AH, Rodriguez SI, Reyes ML, Acosta E, et al. Association of sunlight exposure and photoprotection measures with clinical outcome in systemic lupus erythematosus. P R Health Sci J. 1999;18:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cusack C, Danby C, Fallon JC, Ho WL, Murray B, Brady J, et al. Photoprotective behaviour and sunscreen use: impact on vitamin D levels in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2008;24:260–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2008.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Souto M, Coelho A, Guo C, Mendonca L, Argolo S, Papi J, et al. Vitamin D insufficiency in Brazilian patients with SLE: prevalence, associated factors, and relationship with activity. Lupus. 2011;20:1019–26. doi: 10.1177/0961203311401457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albrecht J, Taylor L, Berlin JA, Dulay S, Ang G, Fakharzadeh S, et al. The CLASI (Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index): an outcome instrument for cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:889–94. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23889.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Caron D, Chang CH. Derivation of the SLEDAI. A disease activity index for lupus patients The Committee on Prognosis Studies in SLE. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:630–40. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glanz K, Lew RA, Song V, Cook VA. Factors associated with skin cancer prevention practices in a multiethnic population. Health Educ Behav. 1999;26:344–59. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geller AC, Glanz K, Shigaki D, Isnec MR, Sun T, Maddock J. Impact of skin cancer prevention on outdoor aquatics staff: the Pool Cool program in Hawaii and Massachusetts. Prev Med. 2001;33:155–61. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santmyire BR, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB., Jr Lifestyle high-risk behaviors and demographics may predict the level of participation in sun-protection behaviors and skin cancer primary prevention in the United States: results of the 1998 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer. 2001;92:1315–24. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010901)92:5<1315::aid-cncr1453>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ragi JM, Patel D, Masud A, Rao BK. Nonmelanoma skin cancer of the ear: frequency, patients’ knowledge, and photoprotection practices. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1232–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman LC, Bruce S, Weinberg AD, Cooper HP, Yen AH, Hill M. Early detection of skin cancer: racial/ethnic differences in behaviors and attitudes. J Cancer Educ. 1994;9:105–10. doi: 10.1080/08858199409528281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buller DB, Cokkinides V, Hall HI, Hartman AM, Saraiya M, Miller E, et al. Prevalence of sunburn, sun protection, and indoor tanning behaviors among Americans: review from national surveys and case studies of 3 states. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:S114–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pichon LC, Corral I, Landrine H, Mayer JA, Norman GJ. Sun-protection behaviors among African Americans. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:288–95. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cress RD, Holly EA. Incidence of cutaneous melanoma among non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, Asians, and blacks: an analysis of california cancer registry data, 1988–93. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:246–52. doi: 10.1023/a:1018432632528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saraiya M, Hall HI, Uhler RJ. Sunburn prevalence among adults in the United States, 1999. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23:91–7. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00461-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sontheimer RD. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: 25-year evolution of a prototypic subset (subphenotype) of lupus erythematosus defined by characteristic cutaneous, pathological, immunological, and genetic findings. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:253–63. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tebbe B, Orfanos CE. Epidemiology and socioeconomic impact of skin disease in lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 1997;6:96–104. doi: 10.1177/096120339700600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

p-values* for demographic and clinical variables versus overall SPH scores and individual photoprotective methods