Abstract

When a word is preceded by a supportive context such as a semantically associated word or a strongly constraining sentence frame, the N400 component of the ERP is reduced in amplitude. An ongoing debate is the degree to which this reduction reflects a passive spread of activation across long-term semantic memory representations as opposed to specific predictions about upcoming input. We addressed this question by embedding semantically associated prime-target pairs within an experimental context that encouraged prediction to a greater or lesser degree. The proportion of related items was used to manipulate the predictive validity of the prime for the target while holding semantic association constant. A semantic category probe detection task was used to encourage semantic processing and to preclude the need for a motor response on the trials of interest. A larger N400 reduction to associated targets was observed in the high than the low relatedness proportion condition, consistent with the hypothesis that predictions about upcoming stimuli make a substantial contribution to the N400 effect. We also observed an earlier priming effect (205–240 ms) in the high proportion condition, which may reflect facilitation due to form-based prediction. In sum, the results suggest that predictability modulates N400 amplitude to a greater degree than the semantic content of the context.

Introduction

In recent years, it has been widely suggested that context-based prediction may play a central role in language comprehension (DeLong, Urbach & Kutas, 2005; van Berkum, Brown, Zwitserlood, Kooijman, & Hagoort, 2005; Staub & Clifton, 2006; Federmeier, 2007; Lau, Phillips, & Poeppel, 2008; Dikker, Rabagliati & Pylkkänen, 2009). Linguistic input is often noisy, variable, and rapid, but it is also subject to numerous deterministic and probabilistic constraints. Predictive processing, based on the constraints imposed by the context, could therefore be particularly useful for speeding up computation and disambiguating noisy input during language comprehension.

One of the most robust indices of contextual support in comprehension is the ERP response known as the N400 effect. A negative deflection peaking at about 400 ms in the ERP waveform is observed in response to many stimuli such as words (auditory and visual) and pictures. When a word is preceded by a supportive context, whether a lexical associate or a predictive sentence or discourse frame, a reduction in the amplitude of the N400 deflection is reliably observed (see Kutas & Federmeier, 2011, for review). Debate continues over whether this N400 reduction reflects contextually facilitated access to stored memory representations or whether it reflects reduced difficulty in integrating new input with prior context and real-world knowledge, but most accounts agree that the N400 effect is at least partially driven by the degree to which the context predicts the target1 (e.g. Federmeier, 2007; van Berkum et al., 2005; see Kutas, Van Petten, & Kluender, 2006, for review).

In this paper we are interested in what the N400 effect tells us about a separate question: does a constraining context influence processing by causing passive interactions between long-term memory representations, or through the generation of specific predictions about what stimulus is likely to appear next? The approach we pursue in the current study is to keep all of the semantic memory relationships between prime and target the same, but to vary the predictive validity of the experimental environment. If contextual facilitation of N400 amplitude is simply a result of spreading activation or ‘resonance’ between memory representations, varying the global predictive validity should not change the size of the effect. However, if N400 contextual facilitation is partially a result of specific predictions about what stimulus (or group of stimuli) is likely to come next in the input, then we would expect a greater N400 reduction when the experimental context encourages participants to make more specific predictions. By the same token, there may be a cost when those predictions turn out to be incorrect.

The N400 and Prediction

One common way of estimating the ‘predictability’ of a given word in a sentence is to present participants with the preceding words in the sentence and to then ask them to provide a completion. Based on the results, one can estimate the probability that a participant would continue the fragment with the word of interest. This is known as the cloze probability (Taylor, 1953). If nearly all participants continue the fragment with the same word, it might be reasonably concluded that the fragment was ‘predictable’, and the cloze probability of that word will be high.

The first indication that the N400 effect might be closely tied to predictability came from the observation that N400 amplitude of a word in a sentence is directly related to the cloze probability of that word; higher cloze probability is associated with a reduction in N400 amplitude (Kutas & Hillyard, 1984). Subsequent work showed that, just as it becomes easier to predict the next word as a sentence progresses, N400 amplitude to words steadily declines across the course of a sentence presented in isolation (Van Petten & Kutas, 1990; 1991). More recently, Federmeier and colleagues have demonstrated that N400 amplitude reduction is observed even for low cloze probability incongruous words (relative to an incongruous control condition) if they share semantic features with high cloze probability words (Federmeier & Kutas, 1999; see also Kutas, Lindamood, & Hillyard, 1984).

However, as van Berkum (2009) points out, effects of cloze probability may be accounted for without appealing to the idea that comprehenders are using the context to guess ahead in this way. Research in the text processing literature has suggested that potentially relevant stored representations become activated through simple passive ‘resonance’-like mechanisms in long-term memory as a comprehender proceeds through a text (e.g., Myers & O’Brien, 1998; Gerrig & McKoon, 1998). Resonance may occur between groups of semantically associated or related words or stored schemas, regardless of the message-level meaning. Previous ERP research, however, has shown that, at least under some circumstances, simple lexical associations, schema-based relationships or other types of simple semantic relationships between words cannot fully account for the N400 effects observed in sentences or discourse (e.g. Van Petten, 1993; Coulson, Federmeier, Van Petten, & Kutas, 2005; Otten & Van Berkum, 2007; Nieuwland & Kuperberg, 2008; Kuperberg, Paczynski, & Ditman, 2011). Nonetheless, it is still possible that more complex conceptual stored representations, such as those associated with common events or states, are activated by the sentence-level or discourse-level message and, in turn, spread activation to associated semantic features of the upcoming word (Sanford, Leuthold, Bohan & Sanford, 2011, Paczynski and Kuperberg, submitted; see Kuperberg et al., 2011 for discussion). On this view, access to a high cloze probability word may be facilitated not because the word is predicted to come next in the input, but because this word or its corresponding concept is among many that are simply associated in memory with stored information, which is passively activated by the context.

In sum, we distinguish between two overall accounts that can both explain why access to a high cloze probability word is facilitated during sentence processing. Both assume that words within context combine to form higher-level representations through structured combination of stored representations. In sentence comprehension, this would include the sentence-level and discourse-level representations of what message the speaker has expressed. For convenience we will refer to this higher-level representation as the contextual representation. The first possibility is that this contextual representation activates stored material, initiating a passive spread of activation that facilitates processing of upcoming words. The second possibility is that this conceptual representation is used to predict and make commitments to specific upcoming items (or features of items). Such predictions could involve pre-activating the conceptual, phonological, and orthographic representations of the word or set of words most likely to appear in the upcoming position. While we believe that both kinds of mechanisms are likely to play a role in processing, the current work is aimed at partialling out their separate contributions.

It is important to note that the stored knowledge that would give rise to either prediction or spreading activation is largely the same. In distinguishing between these two mechanisms we appeal to the existence of some form of working memory or ‘focus of attention’ that holds the contextual representation online (we term this ‘working memory’, although we are not committed to any particular implementation; see Jonides et al., 2007 for a review of ongoing debate in this domain). For us, prediction refers specifically to mechanisms by which the contextual representation, held within working memory, is updated in advance of the actual input. Thus an example of prediction would be if, after processing the fragment She saw a dog chasing a…, the lexical representation of cat is predictively added to the working memory representation of the message being conveyed by the speaker2. In contrast, the passive resonance/spreading activation account only need make reference to the activation level of stored representations in long-term memory. Thus, after processing the fragment She saw a dog…, cat may be activated within long term memory (along with other related words and related semantic features), but it is unlikely that a commitment is made to cat as a continuation, i.e. cat is not actually added to the contextual representation within working memory prior to its onset. Although we distinguish predictions as commitments to the working memory representation, such commitments could have consequences on the activation level of long-term memory representations as well. For example, predictively adding a lexical representation to working memory could result in additional activation of the long-term memory representation over and above what would be expected through more passive spreading activation. In this sense, ‘predictive mechanisms and spreading activation mechanisms may exert effects on the same measure (activation of long-term memory representations) through different routes.

Several previous sentence-level studies have demonstrated convincing evidence for facilitatory effects of lexical prediction with a different kind of paradigm. In these studies the form of a functional element is dependent on a subsequent predicted content word (Wicha, Moreno & Kutas, 2004; DeLong et al., 2005; Van Berkum et al., 2005). For example, DeLong et al. show that when the context strongly predicts a noun beginning with a consonant, such as kite (The day was breezy so the boy went out to fly …) a smaller negativity is observed for the article a relative to the article an, which can only occur before words starting with a vowel and which is thus inconsistent with the predicted noun. Since the critical ERP in those studies is not the response to the predicted word itself, these results provide very strong evidence that lexical prediction occurs in at least some situations. However, these studies are less conclusive about the extent to which classic N400 contextual facilitation effects are due to prediction as compared to passive resonance, as the effects in these studies are typically smaller than those observed at the predicted noun.

Prediction Errors in ERP

Another means of determining whether comprehenders are making predictions is to look for evidence of processing costs when a strongly predicted word is not encountered. Since prediction consists of updating representations in working memory in advance of the input, unfulfilled predictions will require revising this working memory representation. If prediction also results in increased activation of the predicted long-term memory representation, incorrect predictions could also result in increased lexical selection difficulty, as the lexical representation activated by the bottom-up input will have to compete with the highly activated predicted representation. On a passive spreading activation account, however, no commitment is made about what word will appear in a given position, and so no cost should be specifically associated with a strongly predictive context ending unexpectedly—differences in processing should be due only to how much the target was associated with the schemas and scenarios activated by the context and to what extent other competing representations were associated with these schemas and scenarios. Indeed, this lack of cost to unexpected but congruous words is a major feature of memory-based resonance models of text processing (Myers & O’Brien, 1998).

There is some evidence for a cost of unfulfilled prediction in language comprehension. Several studies have compared the ERP response to unexpected but plausible words following strongly predictive or weakly predictive contexts (Federmeier, Wlotko, De Ochoa-Dewald, & Kutas, 2007; DeLong, Urbach, Groppe, & Kutas, 2011; for a review, see Van Petten & Luka, 2012). These studies find no difference in N400 amplitude between these two conditions, but they do observe an increased frontal positivity for unexpected words following the strongly predictive context; Federmeier et al. (2007) observe this difference between 500–900 ms, while DeLong et al. (2011) observe evidence of a positivity as early as the N400 time window (300–500 ms). Federmeier and colleagues interpreted their late positivity as reflecting the cost of overriding or suppressing a strong prediction (an effect that seems to be modulated by visual field presentation; Wlotko & Federmeier, 2007; Coulson & Van Petten, 2007). Otten and Van Berkum (2008) also contrasted the effect of strongly and weakly predictive contexts, but used anomalous endings for both. They also found that the ERP to the critical word following the strongly predictive context was more positive than in the weakly predictive context, in two time-windows (300–500 ms and 500–1200 ms), the effect being more frontally distributed in the early time-window and more widely distributed in the later time-window3. These findings of costs to unpredicted words in constraining contexts provide some preliminary evidence for prediction, but the differences in timing and distribution across studies suggest that converging results are needed.

The Current Study: Relatedness Proportion in Semantic Priming

Our aim in the current study was to test for ERP signatures of lexico-semantic prediction using a different approach. Rather than reading more naturalistic sentence or discourse contexts, we used a relatedness proportion semantic priming manipulation, in which the proportion of semantically associated prime-target pairs changed across the experiment. The drawback of this approach is obviously that reading word pairs is much less similar to real-life language comprehension than reading sentences or short discourses. However, the benefit of this approach is that the design allows us to keep the immediately preceding semantic content of the context exactly identical across conditions, which, as discussed below, would not be possible in a naturalistic design.

Dissociating facilitation due to passive resonance/spreading activation and prediction in sentence and discourse comprehension is challenging, because there is no established way of quantifying complex memory associations of stored scenarios and schemas. Thus it is quite difficult construct stimuli in which the contexts vary in predictability but are exactly matched for semantic association to a target word. Developing strongly and weakly constraining sentence frames also requires extensive norming, and ambiguities can arise about the nature of the weakly constraining contexts—e.g., whether they predict a few endings with equally high probability or numerous endings with low probability. By holding the semantic content constant, the current study is able to avoid all of these problems. Instead, we modulated the likelihood of prediction through changes in the larger experimental context (proportion of related trials in a given block).

Many behavioral studies have demonstrated that increasing relatedness proportion facilitates semantic priming on related trials, as well as having measurable costs on processing of unrelated trials (e.g., Posner & Snyder, 1975; den Heyer, Briand & Dannenbring, 1983; de Groot, 1984; Neely, Keefe & Ross, 1989; Hutchison, Neely, & Johnson, 2001). Several aspects of these results support the hypothesis that effects of relatedness proportion are mediated by a predictive process (Neely, 1977; Becker, 1980). First, relatedness proportion often does not affect processing time in short-SOA paradigms, where automatic spreading activation is thought to support priming effects, and the effect size seems to increase with longer SOAs, where there is more time between prime and target to generate an expectancy set (Posner & Snyder, 1975; Grossi, 2006; Hutchison, 2007). Second, Hutchison (2007) shows that the effect of relatedness proportion on priming is correlated across individuals with measures of working memory and attentional control such as operation span and the Stroop task. As discussed above, we conceive of predictive mechanisms as requiring the generation of expectancies from contextual representations held in working memory. Retrospective strategies such as semantic matching (explicitly assessing the semantic match between prime and target) have also been shown to modulate priming effects in lexical decision paradigms, but factors that increase semantic matching result in a different profile of effects than is observed in relatedness proportion manipulations (Neely, 1991).

Although sentence comprehension clearly involves a number of different processes than those demanded by the relatedness proportion paradigm, the key process of lexical prediction evidenced by the relatedness proportion effect seems likely to be similar to the lexical prediction that we hypothesize occurs during sentence comprehension. Once participants pick up on the fact that many of the word pairs form an associative unit, they begin to try to predict the pair itself as a representation in working memory. In other words, after the prime is encountered, a strongly associated target word is predictively added to a working memory representation of the prime-target pair -- the contextual representation. Importantly, this predictive process is thought only to occur when participants expect word pairs to be associated, as when a high proportion of pairs are associated; if few pairs are associated, lexical facilitation for related targets should only be due to passive priming of representations stored within long-term semantic memory.

Previous observations of relatedness proportion effects on behavioral responses, while suggestive, do not in themselves constitute clear evidence on whether lexical processing is facilitated by prediction. This is because behavioral responses sum effects across multiple stages of processing. Therefore, these effects could be limited to differences in later stages, for example in decision processes required by the lexical decision task. These results also do not address the more specific question of whether N400 amplitude is modulated by prediction over and above the effect of spreading activation, as the N400 does not always track behavioral responses (e.g. Holcomb, Grainger & O’Rourke, 2002).

Several previous ERP studies have provided important preliminary data that addresses these questions. Using a lexical decision task with along SOA (1150ms), Holcomb (1988) showed that the N400 priming effect was larger for targets in a high relatedness proportion block in which participants were instructed to pay attention to prime-target relationships than in a low relatedness proportion block when they were instructed to ignore such relationships. The increased priming effect was due to a reduction in N400 amplitude for related targets, rather than an increased N400 amplitude for unrelated targets, consistent with predictive facilitation (see Kutas & Van Petten, 1988; 1994 for further discussion). Holcomb also found evidence for a larger late positivity to unrelated targets relative to related or neutral targets, which could be interpreted as reflecting the cost of making an incorrect prediction. In a between-subjects design, Brown, Hagoort, and Chwilla (2000) showed that a higher relatedness proportion led to an increased N400 priming effect in a lexical decision paradigm, even when participants were not explicitly instructed to attend to prime-target relationships. Brown and colleagues also showed that the effect of relatedness proportion was not significant in a second experiment in which subjects had no explicit task, and interpreted this as evidence that predictive mechanisms are not a part of normal language processing but are rather due to the lexical decision task itself. Finally, Grossi (2006) showed that relatedness proportion did not modulate the size of behavioral or N400 priming effects in lexical decision when the SOA was only 50ms, consistent with the idea that the effect of relatedness proportion on the N400 reflects top-down predictions that take time to generate.

Although these findings are suggestive, several properties of these studies are less than ideal for isolating the effect of prediction on lexical-semantic processing. In particular, the lexical decision task may not fully engage semantic-level processing, and may instead or additionally engage strategies such as semantic matching that are unlikely to play a role in normal comprehension. Also, in a lexical decision task, targets of interest typically require a motor response, which might contribute differentially to the ERP. For example, if a prime word in the high proportion condition leads to an expectation of a particular related target and an unrelated word target is presented instead, the ‘word’ response may be withheld until the correct representation can be retrieved, and this mismatch in expectation might thus lead to a temporary response conflict in addition to the ‘representational’ conflict at the lexical level. Although the silent reading task used by Brown et al. (2000) has the advantage that it does not require an unnatural lexicality decision, reading a long series of word pairs without any task may be less well-matched to natural comprehension on other properties such as attention to meaning. Shallower semantic processing would be likely to attenuate lexical-semantic prediction, resulting in a smaller relatedness proportion effect. Indeed, although the effect of relatedness proportion on the priming effect failed to reach significance in Brown et al.’s silent reading experiment, the N400 priming effect was numerically larger in the high proportion condition.

In the current study, we used a semantic probe detection task (‘press the button when you see an animal word’), which has several benefits. First, this task requires access to lexical semantics, in contrast to the lexical decision task which in principle only requires access of the wordform, and which therefore may elicit shallower semantic processing. Second, using this task eliminates much of the potential benefit of a retrospective semantic matching strategy; whereas accessing the semantics of the target and assessing the degree of match with the prime word may be an intelligent shortcut in a lexical decision task where directly determining whether the target is an infrequent real word or a nonword is costly, this is not such an obvious shortcut in the semantic probe detection task where a decision can be made immediately upon access of the target word semantics. Third, this task requires no explicit response on the critical targets, which means that response-related contamination of the later ERP time-window is not a concern.

In contrast to Holcomb (1988), in the current study we did not include any discussion of prime-target relationships and did not indicate the existence of two separate blocks in the instructions. In this way, we can conclude that different responses across relatedness proportion are only due to participants implicitly noticing the change in predictive validity across time. We also presented the low proportion block first for all participants. Presenting the high proportion block first is likely to result in significant carryover effects in the low proportion block, as participants continue to assume that the prime is predictive of the target until enough disconfirming evidence is acquired. For this reason, in the current study we chose to always present the low proportion block first, such that in the low proportion block participants would have minimal evidence to support prediction of the target on the basis of the prime. Although factors such as attention and fatigue could shift across the course of the experiment, these kinds of state-level changes would be most likely to lead to a reduction in effect size across time, which would work against our main hypothesis that prediction is associated with increased facilitatory and inhibitory effects.

Our hypotheses were the following. First, semantic priming should lead to a main effect of relatedness, such that targets related to their prime evoke a smaller N400 amplitude than unrelated targets, as shown in many previous studies. Second, if increasing relatedness proportion causes participants to use the prime to predict the target word, and if one consequence of lexical prediction is to further facilitate lexical processing, we should see a quantitative difference in the effect of relatedness proportion: a greater reduction in N400 amplitude for related targets when they are presented in the high proportion block compared to the low proportion block. Third, if passive priming and prediction facilitate the activation of different representations or engage different processing operations, the N400 effect may qualitatively differ across low and high proportion conditions. This difference may be seen in the scalp distribution of the N400. It may also be evident in its timing. For example, if lexical prediction includes pre-activation of sub-lexical representations, the effect of relatedness on the N400 may begin earlier in the high proportion condition. Indeed, the processes involved in generating a lexical prediction may result in differential activity in the ERP for low and high proportion conditions before the target is even presented. If, on the other hand, the only impact of prediction is to facilitate lexical activation, the distribution of the N400 effect due to passive priming and prediction conditions should be the same. Finally, if participants use the prime to predict the target in the high proportion condition, the violation of this prediction in the unrelated targets may result in a frontal positivity, as observed in previous studies of sentence comprehension.

Methods

Materials

Table 1 summarizes the design of the material set used in this study. The experiment comprised a 2 × 2 design (Related/Unrelated × Low/High Proportion). The materials were thus divided into two blocks, a low proportion block and a high proportion block. In the low proportion block, 10% of items were related and in the high proportion block, 50% of items were related. A core set of well-balanced test items were chosen to examine the effect of the two experimental factors, and the proportion manipulation was achieved by intermixing these test items with different proportions of related and unrelated filler pairs. For the purposes of the task a set of animal word probe items was also included in each block. Each block contained 400 item pairs, for a total of 800 item pairs per session.

Table 1.

Distribution of item types across the two blocks of the experiment.

| Low Proportion Block | High Proportion Block |

|---|---|

| 40 related targets | 40 related targets |

| 40 unrelated targets | 40 unrelated targets |

| 40 animal probes | 40 animal probes |

| 280 unrelated fillers | 120 unrelated fillers |

| 160 related fillers |

40 items from each of the 4 experimental conditions were included in the session—40 related and 40 unrelated test pairs in each of the two blocks. In order to prevent item-specific effects, two lists were created for each block so that for any given target, half the participants saw the target preceded by a related prime, and half saw the target preceded by an unrelated prime. To create the set of related and unrelated test pairs, 320 highly associated prime-target pairs were selected from the University of South Florida Association Norms (Nelson, McEvoy & Schreiber, 2004). All pairs had a forward association strength of .5 or higher (meaning >= 50% of participants presented with the prime word responded with the target), with a mean forward association strength of .65. All associated pairs had been previously normed by at least 100 participants. The mean log frequency of the primes was 2.55 and the mean log frequency of the targets was 3.53, as computed in the SUBTLEXus (Brysbaert & New, 2009). Pairs in which there was clear morphological overlap between prime and target were not included. As the probe task required responding to animal words, no pairs including animal words were included in the test items. Two separate, non-overlapping sets of materials were created and rotated across participants (16 participants saw Set 1 and 16 saw Set 2)4. 160 of the related pairs were assigned to each set. The experimental targets in each set were fully counterbalanced across participants (each word could appear in any of the 4 conditions).

160 unrelated test items for each set were then created by randomly redistributing the primes across the target items, and checking by hand to confirm that this did not accidentally result in any associated pairs. For each set, two lists were created with 80 related and 80 unrelated pairs each in a Latin Square design, such that no list contained the same prime or target twice. These lists were then again divided in two, such that 40 related and 40 unrelated pairs were assigned to each block in each list. Forward association strength between prime and target and log frequency for both prime and target, did not significantly differ between test items in each block.

40 probe trials were included in each block (10% of total trials). These probes consisted of a randomly selected prime word followed by an animal word target. The primes in the probe trials were never related to the targets. To achieve the desired relatedness proportion in each block, 280 unrelated filler trials were included in the low proportion block such that only 10% of the trials were related, and 120 unrelated filler trials and 160 related filler trials were included in the high proportion block such that 50% of the trials were related. The related filler pairs were also selected from the South Florida Association Norms. Because the number of related and unrelated fillers differed across blocks, these items could not be counterbalanced to guard against item-specific effects and are not analyzed here. No word in any position was ever repeated in a given presentation list (stimuli available at http://kuperberglab.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/materials.htm). The low-proportion block was always presented first.

Participants

Participants were drawn from the Tufts University community and participated in the study in return for monetary compensation. The data presented here come from 32 participants (13 men, 19 women) aged 19 to 24 years (mean age = 20.5 years) whose data satisfied the inclusion criteria described below. All participants were native speakers of American English who had not learned another language before the age of 5, and were right-handed as assessed by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield, 1971). Participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and had no history of reading disability or of neurological disorders. Prior written consent was obtained from all subjects according to established guidelines of Tufts University.

Stimulus Presentation

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four counterbalanced lists from one of the two materials sets. During the experiment participants were seated in a comfortable chair in a dimly lit room separate from the experimenter and from presentation and recording computers. Stimuli were visually presented on a computer monitor in yellow 20-point uppercase Arial font on a black background. Each trial began with a fixation cross, presented at the center of the screen for 700 ms, followed by a 100 ms blank screen. The prime word was then presented for 500 ms, followed by a 100 ms blank screen, and then the target word was presented for 900 ms, followed by a 100 ms blank screen. Participants were instructed to press a button on a handheld response box with their right thumb as quickly as possible when they saw the name of an animal. Participants were given a short break after every 100 trials, resulting in a total of 8 runs of about 5 minutes each. Each participant was given 16 practice trials at the beginning of the experiment.

Electrophysiological Recording

Twenty-nine tin electrodes were held in place on the scalp by an elastic cap, in a modified 10–20 configuration (Electro-Cap International, Inc., Eaton, OH). Electrodes were also placed below the left eye and at the outer canthus of the right eye to monitor vertical and horizontal eye movements, and over the left (reference) and right mastoids. Impedance was kept less than 5 kOhms for all scalp electrode sites, less than 2.5 kOhms for mastoid sites, and less than 10 kOhms for eye electrodes. The EEG signal was amplified by an Isolated Biolectric Amplifier System Model HandW-32/BA (SA Instrumentation Co., San Diego, CA) with a bandpass of 0.01 to 40 Hz and was continuously sampled at 200 Hz by an analog-to-digital converter. The stimuli and the behavioral responses were simultaneously monitored by the digitizing computer. Recordings were preceded by a brief run of calibration pulses, which were used to re-calibrate the EEG signal offline.

Data Analysis

Averaged ERPs, time-locked to target words were formed off-line from trials free of ocular and muscular artifact using preprocessing routines made available by the EEGLAB (Delorme & Makeig, 2004) and ERPLAB (erpinfo.org/erplab) toolboxes. Only trials in which participants responded or withheld a response correctly before the onset of the next trial were included in the target averages. One subject with fewer than 20 surviving trials in any condition was excluded from further analysis and is not included in the 32-participant dataset presented here. Across the 32 participants included in the analysis, approximately 10% of trials were rejected due to artifact. Trials in which participants responded incorrectly were also excluded from further analysis. A 100-ms pre-stimulus baseline was subtracted from all waveforms prior to statistical analysis. For graphical presentation only, a 15Hz low-pass filter was applied to the data to create the figures.

In order to assess our primary hypothesis that high relatedness proportion would increase N400 priming, we used R (R Development Core Team, 2010) to compute a repeated-measures Type III SS analysis of variance on mean ERP amplitudes between 300–500 ms post-stimulus onset across all sites, with relatedness and proportion as the experimental factors of interest. This was followed by specific analyses designed to test for effects of proportion on the topographical distribution and timing of the N400 priming effect, using the difference waveforms obtained by subtracting the unrelated and related responses within each level of proportion. Topographical distribution of the priming effect in the 300–500 ms time-window was assessed using a subset of 20 electrodes divided into two levels of hemisphere (left/right) and two levels of anteriority (anterior/posterior) defining four quadrants (left anterior: FP1, F7, F3, FC5, FC1; right anterior: FP2, F8, F4, FC6, FC2; left posterior: CP5, CP1, T5, P3, O1; right posterior: CP6, CP2, P4, T6, O2). To assess our secondary hypothesis that high relatedness proportion would result in an increased late positivity in the response to unrelated targets, we conducted a repeated-measures ANOVA on mean ERP amplitudes between 500–800 ms post-stimulus onset across all sites, with prime and proportion as the experimental factors. Because none of the ANOVAs conducted here included more than one degree of freedom in the numerator, no correction for violations of sphericity was needed (Greenhouse & Geisser, 1959).

Onset latency of the N400 priming effect was assessed with a nonparametric cluster-based permutation test at electrode Cz, a site at which the N400 effect is usually at or near its maximum. For low-proportion and high-proportion pairs separately, we conducted paired t-tests contrasting the response to related and unrelated targets at every sample between 100 ms and 500 ms. We then corrected for multiple comparisons by using the cluster-based permutation test implemented in the FieldTrip toolbox (Oostenveld, Fries, Maris, & Schoffelen, 2011) to estimate the number of temporally contiguous significant t-tests (p < .05) likely to arise by chance. In particular, we randomly permuted the condition labels for each set of individual subject averages, computed the associated t-test across all time-samples between 100:500 ms, and summed the t-values from temporally contiguous clusters of samples. We then saved the largest cluster t-sum in this random permutation, and repeated this procedure 1000 times to create a distribution of the size of the maximum cluster t-sum arising by chance. We estimated the onset of the N400 priming effect in the two proportion conditions as the time of onset of the first temporal cluster with a t-sum falling within the p < .05 confidence interval of the permutation distribution.

Finally, we conducted exploratory analyses comparing the response to animal probe words and to prime words across low proportion and high proportion conditions. We hypothesized that increased prediction in the high proportion condition might result in a prediction violation cost in the animal probes (never associated with their prime) and might also elicit some correlate of prediction formation during the prime word. As we did not have a priori hypotheses about which time-window or electrodes would demonstrate such effects, we tested all electrodes and time-samples that could be expected to show an effect (100–900 ms post-onset for the animal probe and 100–600 ms post-onset for the prime) for significant differences (α = .05) using a permutation test over the tmax statistic to control for multiple comparisons (Groppe, Urbach & Kutas, 2011).

In order to conserve space, the figures in the main text illustrate the response waveforms at representative sites of interest only. Waveforms illustrating the response across all sites are available as Supplementary Figures at http://kuperberglab.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/materials.htm.

Results

Behavioral Results

Participants were only required to make a response when they identified an item from the target category. Only responses within 1000 ms of target onset (before the onset of the subsequent trial) were considered. Accuracy in not responding to (non-animal) experimental targets was above 99% for all conditions. Mean accuracy in identifying animal probe words was 93.9% (SD = 6.6%) in the low proportion block and 94.5% (SD = 4.2%) in the high proportion block, thus showing no appreciable effects of proportion. Mean response times were 632 ms (SD = 51 ms) in the low proportion condition and 651 ms (SD = 45 ms) in the high proportion condition. A paired-sample t-test showed that this RT difference was significant (t(31) = 3.23, p < .01), indicating that participants were slower to respond to probe items in the high proportion condition in which prediction was encouraged.

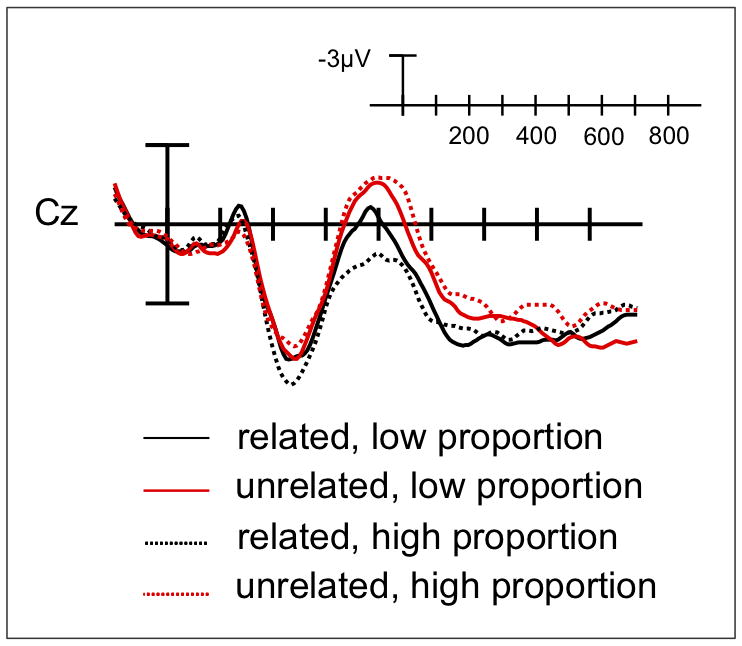

ERP Results

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the N400 response to related and unrelated trials in the 10% related block and the 50% related block. To preview the main results, we observed a classic N400 effect of semantic priming (unrelated target more negative than related target) in both blocks, but consistent with our hypothesis, the N400 effect was larger in the high proportion block than in the low proportion block. The distribution of the N400 effect was somewhat different across the two blocks, and the onset of the priming effect was earlier in the high-proportion condition. In the high proportion condition, we also observed a late widespread negativity to unrelated targets and an increased P3 component on (unrelated) probe animal targets.

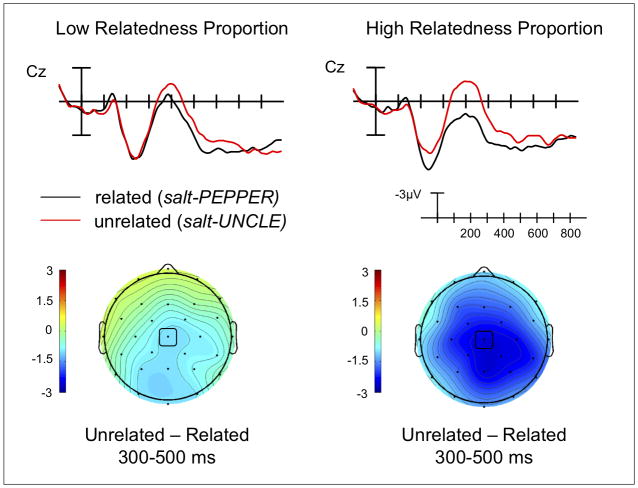

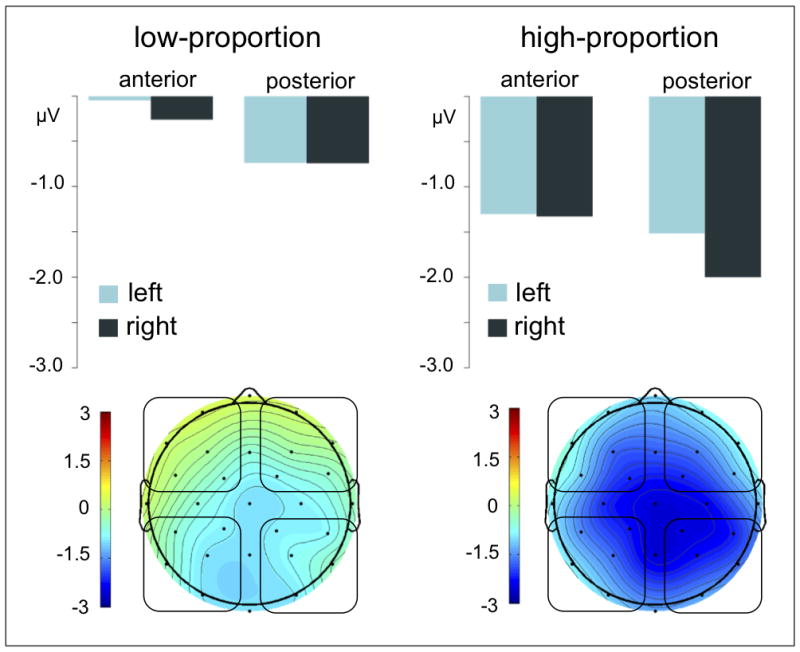

Figure 1.

Grand-averaged waveforms to target words following related and unrelated primes under conditions of low and high relatedness proportion at site Cz. Voltage maps comparing ERPs evoked by the target between 300 and 500 ms (unrelated – related) for each level of relatedness proportion. See Supplementary Figures 1–2 for full 32-electrode waveform maps at each level of relatedness proportion.

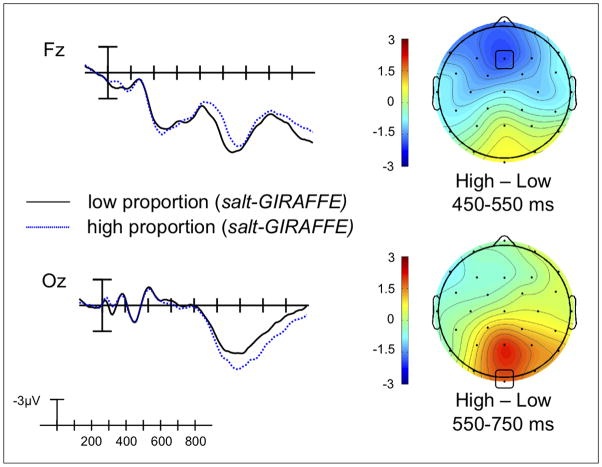

Figure 2.

Grand-averaged waveforms to target words following related and unrelated primes under conditions of low and high relatedness proportion at site Cz.

Effect of relatedness proportion on size of N400 priming effect

Repeated measures analysis of variance in the 300–500 ms time-window across all sites demonstrated a main effect of relatedness (F(1,31) = 26.5; p < .01) and a significant interaction between relatedness and proportion (F(1,31) = 12.3; p < .01). This interaction was due to a larger effect of relatedness in the high-proportion condition than in the low-proportion condition (low related: 1.38 μV, low unrelated: .90 μV, high related: 2.13 μV, high unrelated: .52 μV). Planned comparisons at each level of proportion demonstrated that the effect of relatedness (related vs. unrelated) was significant in both the low-proportion (t(31) = 2.05; p < .05) and high-proportion blocks(t(31) = 5.67; p < .01). This indicates that the interaction between relatedness and proportion was driven by a difference in the magnitude of the priming effect across blocks, rather than the absence of a priming effect in the low-proportion block.

We hypothesized that facilitative effects of fulfilled prediction would be observed at the N400 and conflict effects of unfulfilled prediction would be observed later, but the interaction between relatedness proportion and priming at the N400 could also, in principle, reflect an increase in N400 amplitude for high-proportion unrelated targets. However, visual inspection clearly indicates that the unrelated targets are matched in N400 amplitude at centro-parietal electrodes across the high and low proportion blocks, in contrast to the related targets, which elicit a reduced N400 amplitude in the high-proportion block (Figure 2). Consistent with this, planned comparisons at each level of relatedness demonstrated that proportion (low vs. high) had a significant effect on the response to related targets (t(31) = 2.7, p = .01), while the effect of proportion on the unrelated targets did not reach significance (t(31) = 1.79, p = .08).

Effect of relatedness proportion on the topographical distribution of the N400 effect

A quadrant analysis of the difference waves representing the priming effect (unrelated-related) in the 300–500 ms time-window revealed differences in the topographical distribution of the N400 priming effect across low and high proportion conditions. Repeated measures analysis of variance across 20 electrodes coded for hemisphere (left/right) and anteriority (anterior/posterior) demonstrated a significant 3-way interaction between proportion, hemisphere, and anteriority (F(1,31) = 12.9; p < .01). Figure 3 illustrates these differences in distribution. The priming effect in the high-proportion or ‘prediction’ condition appears largest in the right posterior quadrant, with the other three quadrants showing effects of relatively equal amplitude. This contrasts with the posterior but more symmetrical distribution observed in the low-proportion condition.

Figure 3.

Quadrant analysis of N400 priming effect (amplitude difference between unrelated and related targets during the 300–500 ms time window). Bar plots comparing grand-average amplitude differences in each of four quadrants indicated on voltage maps, for each level of relatedness proportion. Voltage maps comparing average ERP amplitude difference between unrelated and related targets between 300–500 ms for each level of relatedness proportion.

To determine whether these visually apparent differences were indeed driving the 3-way interaction, follow-up 2×2 ANOVAs (hemisphere × anteriority) at each level of proportion were conducted. In the high proportion condition, there were no significant main effects of anteriority (F(1,31)=1.2) or hemisphere (F(1,31)=.8), but there was a significant interaction between anteriority and hemisphere (F(1,31) = 7.4, p < .01), supporting the visual impression that the high proportion effect was particularly focused over right posterior electrodes. In the low proportion condition, however, there was a significant main effect of anteriority (F(1,31) = 4.52, p < .05), driven by a larger priming effect over posterior than anterior electrodes, but neither the main effect of hemisphere (F(1,31) = .3) nor the interaction between anteriority and hemisphere (F(1,31) = 1.8) were reliable.

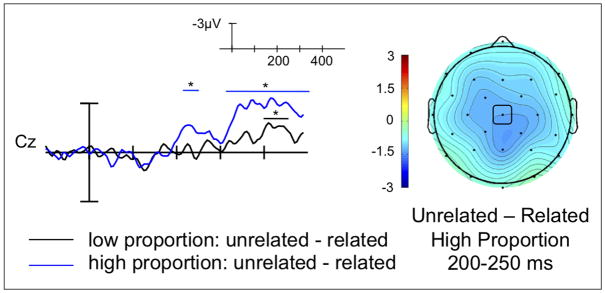

Effect of relatedness proportion on the onset latency of the N400 effect

Figure 4 illustrates the timing of the onset of the priming effect in the low and high proportion conditions at electrode site Cz. Cluster-based permutation tests at Cz (see Methods) showed that in the high-proportion, predictive condition, the unrelated and related conditions began to show a significant difference at 205 ms (the first cluster of samples showing a significant difference were 205:240 ms; the second cluster begins at 315 ms and continues to 500 ms, the end of the epoch tested). In contrast, in the low-proportion condition, the unrelated and related conditions differ significantly only at 400 ms (400:455 ms); a marginally significant cluster (p < .12) spanned the 350:365 ms time-window. The topographical map of the high-proportion priming effect between 200:250 ms is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Grand-averaged difference waves reflecting the priming effect (unrelated – related) at site Cz for each level of relatedness proportion. Time-windows showing a significant priming effect (p < .05) in the latency onset analysis are indicated. Voltage map comparing ERPs evoked by the target between 200–250 ms (unrelated – related) in high relatedness proportion condition.

To confirm the visual impression that the onset latency of priming effects at Cz was consistent across many electrode sites, we tested the effect of relatedness averaged across all electrode sites within each level of relatedness proportion for the 200–250ms time-window and the 400–450ms time-window. Consistent with the results of the latency analysis at Cz, between 200–250ms the effect of relatedness was significant in the high proportion condition (t(31) = 3.1, p < .01) but not in the low proportion condition (t(31) = .3, p > .7), while in the 400–450ms time-window, the effect of relatedness was significant in both the high proportion condition (t(31)=6.7, p < .01) and the low proportion condition (t(31)=2.6, p < .05).

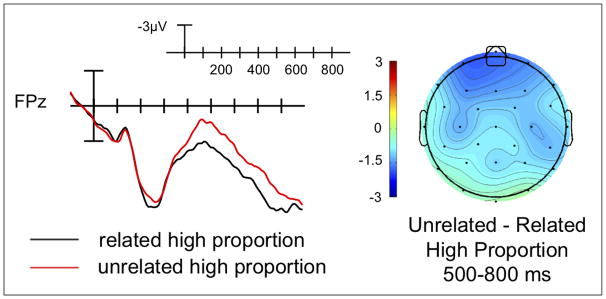

Effects of unfulfilled prediction on targets

ERP modulation also differed between the low and high proportion conditions in the later, 500–800 ms time-window. A repeated measures analysis of variance across all electrodes in this time-window demonstrated a significant main effect of relatedness (F(1,31) = 12.9, p < .01) and, most notably, a significant interaction between relatedness and proportion (F(1,31) = 4.9, p < .05). We hypothesized that the mismatch between the predicted target and the actual target in the high-proportion unrelated condition would lead to a late frontal positivity relative to the low-proportion unrelated condition. However, visual inspection of the waveforms suggests that we observed no such effect. In fact, in the same time-window in which Federmeier et al. (2007) showed an increased positivity, planned comparisons at each level of relatedness proportion revealed a significantly increased negativity effect to unrelated (versus related) targets in the high proportion condition (t(31)=4.06, p < .01) over many electrode sites, but not the low proportion condition (t(31)=1.1, p >.1), as shown in Figure 5. To further explore the distribution of this larger late negativity to the unrelated targets appearing in the high versus low proportion condition, we conducted quadrant analyses at each level of relatedness proportion (low, high: relatedness × hemisphere × anteriority), but we found no significant interactions between relatedness and either distributional factor (all ps > .1).

Figure 5.

Grand-averaged waveform to target words following related and unrelated primes in the high relatedness proportion condition at site FPz. Voltage map comparing ERPs evoked by the high relatedness proportion targets between 500 and 800 ms (unrelated – related), the time-window expected to show costs of prediction violation. See Supplementary Figures 3–4 for full 32-electrode waveform maps at each level of relatedness.

Effects of relatedness proportion on animal probes

Animal probes (the semantic category for which participants were monitoring) elicited a P3 component in both blocks, as expected for a task-relevant stimulus. However, these trials also constituted a special case of unrelated targets, and therefore could also be expected to show an increased prediction cost with increasing relatedness proportion. Indeed, visual inspection suggested that the amplitude of the P3 was larger in the high proportion block (Figure 6).

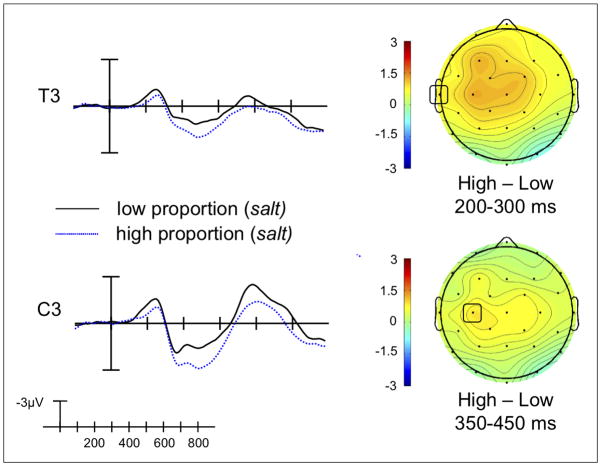

Figure 6.

Grand-averaged waveforms to probe words (following unrelated primes) under conditions of low and high relatedness proportion at two sites that showed a significant difference between conditions. Voltage maps comparing ERPs evoked by probe words under conditions of low and high relatedness proportion. See Supplementary Figure 5 for full 32-electrode waveform map.

Because we did not have prior hypotheses about the time-window in which the response to probes would differ, we tested all electrodes and time-samples (100–900 ms post-stimulus onset) for significant differences using a permutation test over the tmax statistic to control for multiple comparisons (critical t-score: +/− 4.720, test-wise alpha: p < .000048). This procedure revealed differences in two time-windows: several frontal electrodes were significantly more negative in the high than the low proportion condition in samples falling between 490–515 ms (Fz, F3, and FPz), and Oz was significantly more positive in the high than the low proportion condition between 585–600 ms and 675–680 ms.

Effects of relatedness proportion prior to target presentation

If increasing proportion results in increased prediction of the target based on the prime, we might expect to see effects of proportion prior to the target, either due to differences in how the prime is processed when it will be used to make a prediction, or due to the processes involved in forming the prediction itself. We therefore also conducted an exploratory analysis in the time-window between the onset of the prime and the onset of the target (100–600 ms post-prime onset, in other words corresponding to -500-0 ms pre-target onset). In this analysis we included primes for related targets, unrelated targets, and animal probes, as these lexical items were counterbalanced across conditions; this resulted in a total of 120 items per prime type (low proportion or high proportion) per participant. We used a permutation test over the tmax statistic to control for multiple comparisons (critical t-score: +/− 4.405, test-wise alpha: p < .00017). This procedure revealed electrodes showing significant differences in two time-windows. Between 245–250 ms, electrode T3 was significantly more positive for primes in the high proportion condition, and between 375–380 ms, electrodes C3 and CP5 were also significantly more positive in the high proportion condition (all ps < .05, corrected). Although only these electrodes and time-samples were reliable by this conservative criteria, visual inspection suggested that the response to primes in the high proportion condition showed a broad, slightly leftward positivity relative to primes in the low proportion condition between 200–300 ms and 350–400 ms (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Grand-averaged waveforms to prime words under conditions of low and high relatedness proportion at sites showing a significant difference between conditions. Voltage maps comparing ERPs evoked by prime words under conditions of low and high relatedness proportion (high – low). See Supplementary Figure 6 for full 32-electrode waveform map.

Discussion

In this experiment we used a relatedness proportion paradigm to manipulate the predictive validity of the prime word while keeping the local context constant. A semantic category probe task was used to encourage processing of target meaning, without requiring participants to execute motor responses on trials of interest. We show that increasing relatedness proportion—a manipulation previously argued to encourage predictive processing (Neely, 1977)—is associated with a substantially larger N400 reduction for related targets. These results are consistent with previous ERP studies demonstrating increased N400 facilitation with increased relatedness proportion (Holcomb, 1988; Brown, Hagoort, & Chwilla, 2000). We also show that the unrelated and related targets diverge earlier when relatedness proportion is increased, and that the topographical distribution of the effect of relatedness is different under low and high proportion conditions.

Contrary to our original hypothesis, increased relatedness proportion did not result in a larger frontal positivity due to prediction mismatch in the unrelated (and thus, unpredicted) targets. Rather, increased relatedness proportion was associated with a broadly-distributed late negativity to unpredicted targets. However, increased relatedness proportion was associated with a larger late positivity to unrelated animal probes, which required an explicit motor response.

Effects of prediction on N400 amplitude

As argued in the Introduction, distinguishing between passive spreading activation and prediction accounts of the N400 is difficult using sentence- or discourse-level stimuli. Any manipulation in contextual constraint or predictability might well lead to differences in association between the context and the target item. An important contribution of the present study is to show that prediction strength alone can modulate the N400 effect, without any change in the content of the immediate context. This indicates that the N400 priming effect does not only reflect spreading activation between items in long-term memory. Rather, N400 amplitude appears to be sensitive to the degree to which the reader predicts the target to be related to the prior context.

One potential alternative explanation for the N400 effects of relatedness proportion observed here is that they were due to their relative positioning in the experiment. Following previous studies, the high proportion block was always presented second in order to ensure that participants be naïve to the possibility that the prime could serve as a valid predictor for the target during the low proportion block. Therefore, one might argue that the differences between blocks were due to some low-level property associated with their order (e.g. attention, motivation) rather than the relatedness proportion manipulation itself. Although we cannot dissociate relatedness proportion from trial order in the current paradigm, we do not believe that trial order itself provides a good account for the results we observe here. The primary reason is that most of the low-level variables that would normally be associated with trial order would seem to predict reduced effect sizes for a non-task-relevant manipulation as the experiment proceeds, such as lower attention and lower motivation. Despite this, we in fact saw a bigger priming effect in the second half of the experiment, which receives a natural explanation through the change in the proportion of related primes. A more plausible variant on the trial order account is that the modulation of N400 priming is indeed driven by increased prediction, but that it is the number of related pairs encountered rather than the proportion which drives the shift to prediction, so that after a long enough time in a low-proportion regime participants would still begin using the prime to predict the target. This is an interesting possibility that relates to the broader question of how the properties of the prior input modulate predictive strategies in general, but even if correct it would not alter our central conclusion, that modulation of prediction strength results in modulation of the N400 effect.

The effect of prediction on the N400 could be realized in several ways. Most straightforwardly, in strongly predictive contexts, participants may hold the prime in working memory and use this representation to actually pre-activate lexical representations of strong associates which are added to working memory prior to the appearance of the target. As a result, lexical processing as reflected by N400 amplitude would be easier when one of those associates is actually presented. This account is consistent with work suggesting that the N400 effect is at least partially due to facilitated activation of lexical-conceptual information in long-term memory (Kutas & Hillyard, 1984; Kutas & Federmeier, 2000; Lau et al., 2008).

However, we should consider whether the current effects of contextual predictability on priming can be explained without assuming that participants pre-activated the target words (or their semantic features) before they are presented. For example, initial activation of the target could be based on purely bottom-up information, but in an environment with high predictive validity participants might be more likely to bring prior context into a later stage of processing (as in for example, Marslen-Wilson’s (1987) model of lexical processing in context). Another possibility is that when the prime has more predictive validity, participants process the prime more ‘deeply’ so that it is able to passively spread more activation to associated memory representations (although on this account one might predict greater absolute N400 amplitude for high-proportion primes, while we in fact observed the opposite).

While these alternative hypotheses could explain the pattern of N400 modulation observed here, several aspects of the current results lead us to favor the predictive account. First, the N400 effect had a reliably different topography in the high proportion condition, suggesting a qualitative difference in mechanism. Second, we observed that the effect of the prime context began earlier in the high proportion condition. These results, discussed further below, can be straightforwardly explained if predictive mechanisms are selectively invoked in this condition, but are harder to explain if context is only used in a later stage or if the shift from low to high proportion only results in an increase of the same spreading activation mechanism. As discussed in the Introduction, there is also evidence from sentence-level studies for lexical prediction effects prior to the onset of critical words (Wicha et al., 2004; DeLong et al., 2005; Van Berkum et al., 2005). Finally, if the relatedness proportion effect were simply due to ‘deeper’ processing of the prime it would seem to predict that accuracy of detecting an animal probe in the prime position would also be higher, but in a recent replication that included animal probes in both prime and target position, we found no difference in the rate of detection across high and low proportion blocks even though the overall detection rate was well below ceiling (Lau et al., in preparation).

The fact that a small but reliable N400 priming effect was observed in the low proportion condition suggests that N400 facilitation may not be completely attributable to predictive processes. This is consistent with previous work demonstrating N400 priming effects under conditions thought to elicit more automatic processing, such as N400 semantic priming at short SOAs (Anderson & Holcomb, 1995; Deacon et al., 1999; Franklin et al., 2007), priming of targets that are only indirectly associated with their primes (Chwilla, Kolk, & Mulder, 2000; Kreher, Holcomb & Kuperberg, 2006) and at least semi-conscious masked semantic priming (Kiefer, 2002; Holcomb, Reder, Misra, & Grainger, 2005; Grossi, 2006). Retrospective semantic processes such as semantic matching have also been shown to elicit N400 effects (Chwilla, Hagoort, & Brown, 1998) and thus could also have contributed to the low proportion N400 effect here, although the use of a semantic probe task may have made this less likely. We also take the presence of an N400 priming effect in the absence of prediction to be consistent with more recent work at the sentence and discourse level showing N400 facilitation for targets which are not predictable, and which are not necessarily semantically related to the predicted item, but which are plausibly associated with other individual words in the context (Camblin et al., 2007; Ditman, Holcomb, & Kuperberg, 2007; Boudewyn et al., 2011) or related to the overall stored schema activated by the context (Paczynski & Kuperberg, submitted; Sanford et al., 2011). Because semantic relatedness between individual words in context is unlikely to be predictive of upcoming material in typical comprehension, sentences or discourses containing such associations are more akin to our low proportion condition than our high proportion condition, and their effects may be mediated through more passive resonance mechanisms. This may also account for why, in sentence and discourse paradigms, effects of lexical association independent of the message-level representation have tended to be relatively smaller and more variable (Carroll & Slowiaczek, 1986; Morris, 1994; Morris & Folk, 1998; van Petten et al., 1997; Traxler, 2000; Camblin et al., 2007; Boudewyn et al., 2011).

Together, these results suggest that spreading activation and prediction may play complementary roles in preparing the comprehender for upcoming material; while spreading activation is less focused than prediction, it can provide some processing benefit even when the context does not make specific predictions available.

Effect of prediction on the distribution of the N400 effect

Distributional analyses suggested that the topographical distribution of the N400 effect differs according to whether the context actually predicts the target rather than simply being semantically associated. This was demonstrated by a significant three-way interaction between relatedness proportion, anteriority, and laterality in the amplitude of the relatedness effect. Follow-up tests showed that the N400 priming effect in the low proportion ‘associative’ condition was larger in posterior electrodes but was not reliably different across hemispheres, while the N400 effect in the high proportion ‘predictive’ condition showed an interaction between hemisphere and anteriority that seemed to be driven by the fact that the N400 effect was largest across right posterior electrodes. This pattern is somewhat consistent with the results of Otten and Van Berkum (2007), who created contexts in which the content words and the scenarios suggested by them were similar, but the message-level prediction for the critical word position differed due to the presence or absence of negation. They showed N400 effects of both association and message across left hemisphere electrodes, but only effects of message across right hemisphere electrodes. They argued that the effects of message indexed prediction, while the effects of lexical- and scenario-level association reflected effects of a more passive resonance, analogous to the low-proportion condition in the present study.

These differences in distribution have two main consequences. First, they suggest that the differences in contextual facilitation observed between the low and high proportion conditions do not simply reflect differences in the magnitude of the facilitation, but may index qualitatively different processes. This supports the hypothesis that increasing relatedness proportion causes predictive mechanisms to be invoked, and argues against explanations of relatedness proportion effects as simple increases in the magnitude of passive priming. Of course, even if low and high proportion conditions are associated with qualitatively different mechanisms of contextual facilitation, it could have been the case that their end result—facilitation of lexical processing—was empirically indistinguishable in the response to the target. The fact that this is not the case is encouraging because it suggests that, with more research, we may be able to develop neural signatures for facilitation due to prediction as compared to facilitation due to association only.

Second, the particular distributions we observed are suggestive with respect to the question of whether these results can be taken as evidence for lexical prediction in typical sentence and discourse comprehension. In particular, previous ERP studies of contextual facilitation in sentences have shown a fairly consistent right centro-parietal focus to the N400 effect when stimuli are presented in the visual modality (see Van Petten & Luka, 2006 for a review). The fact that the N400 effect in the ‘predictive’ high proportion condition showed a scalp distribution more similar to these sentence N400 effects than the ‘associative’ low proportion condition might then be taken as one piece of preliminary evidence that the N400 effects seen in more natural language comprehension paradigms at the sentence and discourse levels are partially due to predictive facilitation. Interestingly, the studies demonstrating an N400 attenuation to words that fit with the schema activated by the context but that are incongruous with the precise message-level meaning of the context (e.g. Paczynski & Kuperberg, submitted; Sanford et al., 2011), report an N400 effect that does not have this classic right-posterior distribution. As noted above, these findings are not so easily explained by prediction and have been attributed to a more passive spread of activation within semantic memory. The current results and those of Otten and Van Berkum (2007) are consistent with this interpretation. Future work aimed at dissociating passive priming from prediction should test for topographical similarity more carefully, as the differences we observed were statistically reliable but easy to overlook in casual visual inspection.

Effects of prediction on N400 onset latency

We also observed a significant effect of prediction on the onset latency of the context effect. At electrode Cz the difference between unrelated and related targets in the low proportion block only reached marginal significance at 345 ms, while the high proportion block showed significant differences between 205:240 ms as well as 315:500 ms. One possibility is that this early difference reflects the same processes as differences in the more canonical 300–500ms N400 time-window, and that the difference in onset latency is a simple result of the smaller effect size in the low proportion condition (an ‘iceberg’ effect). Alternatively, the early effect in the high-proportion condition may reflect an effect of context on target processing that is specific to prediction. While more targeted studies will be needed to determine whether this early effect is qualitatively different from ‘classic’ N400 effects, below we briefly discuss some possible candidate mechanisms should this turn out to be the case.

Some authors have recently argued that the early phase of so-called N400 context effects in the 200–350 ms time-window may be specific to targets that are very strongly predicted by the context and may thus reflect a qualitatively different process from effects in the later part of the N400 time-window (Roehm et al., 2007; Vespignani et al., 2010; Molinaro & Carreiras, 2010). In particular, these authors note that in paradigms that allow prediction of a particular word, such as idioms or frequent collocations, the early part of the N400 amplitude difference appears to be driven by an increased positive deflection relative to baseline in the predicted condition, much as is visible for the high proportion related targets in the current study. This early deflection is argued to be part of the P300 family, as it seems to be partially dependent on whether the context-target relationship is relevant for the task (Roehm et al., 2007). Vespignani, Molinaro and colleagues suggest that the early positive deflection reflects ‘closure of an expectation’ or a ‘monitoring process’ (Vespignani et al., 2010; Molinaro & Carreiras, 2010), and associate the positive deflection observed for collocations with the P325 observed in masked priming studies (Holcomb & Grainger, 2006; Carreiras et al., 2009; although we would note that the P300 observed to probe words in the current study peaked significantly later than 325 ms).

The timing of the early effect observed here (significant between 205–240 ms) was in fact somewhat earlier than 300 ms. Therefore we suggest that the early effect in the high-proportion condition may rather correspond to the processes underlying the ‘N250 effect’ observed in masked priming studies by Holcomb, Grainger and colleagues (see Grainger & Holcomb, 2009, for review). The positive polarity of our early effect relative to baseline obviously differs from the N250 observed in masked priming studies, but this is relatively uninformative since the ERP to masked priming targets includes sensory responses to the mask and the prime overlaid on the response to the target itself. The topographical distribution we observe for the early effect in this study was also not unlike that reported in masked priming studies, being a bit more anteriorly distributed than the classic N400 effect (Grainger & Holcomb, 2009). In masked priming studies the N250 component is sensitive to the degree of orthographic overlap between prime and target for both real words and pseudowords. In our non-masked, long-SOA study, the N250 effect would instead arise from orthographic overlap between the predicted target and the actual input. If the high predictive validity of the prime word leads to a strong prediction for a particular target in our high-proportion condition, this might be realized as not only a prediction for the conceptual representation associated with the predicted lexical item, but also a form-based prediction for the orthographic representations that make up the word.

A related possibility is that the early effect in this study reflects a frontal P2. Federmeier, Mai, and Kutas (2005) observed a significant difference between strongly and weakly predicted endings in frontal electrodes between 200–300 ms. This difference was larger for endings presented to the left hemisphere (right visual field) than endings presented to the right hemisphere (left visual field). Federmeier et al. argued that this effect reflected modulation of the P2 component—which has been previously linked to visual feature extraction—and therefore that top-down information from the sentence context must allow for more efficient visual feature extraction when the target is highly predicted.

Several recent studies provide additional suggestive evidence that lexical-semantic or syntactic predictions may in turn be realized as form-based predictions (Dikker et al., 2009; Groppe et al., 2010; Kim & Lai, in press). Other studies using highly predictive contexts may have failed to observe such an early effect because they have generally focused on the time-window centered around the peak of the N400 effect, rather than specifically examining the onset of the effect. However, further work will be needed to determine whether this effect is qualitatively distinct from the N400 effect and whether it can be observed reliably across different studies and different types of predictive contexts.

Effects of instantiating predictions

Given the evidence that our relatedness proportion manipulation was successful in modulating prediction strength, one intriguing possibility is that we might be able to see evidence for the instantiation of a prediction by comparing the ERP to primes in the low proportion (less predictive) condition with primes in the high proportion (more predictive) condition. Of course, this would require that the process of instantiating a prediction is tightly time-locked to presentation of the contextual information, and it is not obvious that this should be the case. However, an exploratory analysis indicated some differences in the ERPs to low-proportion and high-proportion primes. In particular, the response to high-proportion primes was more positive across several left fronto-central electrodes in the P2 and N400 time-windows. This result is somewhat consistent with Holcomb’s (1988) observation that the response to the prime was more positive between 300–650 ms for high vs. low proportion, although there the effect was greatest over parietal electrodes. While the functional interpretation of these differences is unclear, the left-lateralization of the effect in the current study is at least consistent with previous suggestions that left hemisphere areas are involved in instantiating predictions (Federmeier, 2007; Dikker, 2010). Although inconclusive, we hope that these data may stimulate further work aimed at determining the neural signatures of prediction formation.

Effects of unfulfilled predictions on targets

Although previous studies have identified an increased frontal positivity as one marker of prediction cost (see Van Petten & Luka, 2012, for review), there was no sign of a positivity for unrelated targets relative to related targets with increased prediction strength, although there was a positivity on unrelated targets where people made actual responses. One possibility is that in this paradigm, there simply is not a significant lexical processing cost for predicting the wrong word in the absence of response conflict. One difference between this study and several previous studies that observed frontal positivities associated with prediction cost (Federmeier et al., 2007, DeLong et al., 2011) is that the current study used single-word contexts rather than sentences. Therefore it could be the case that these frontal positivities reflect processes that are more likely to be engaged during sentence or discourse-level processing. For example, they may reflect a cast of undoing a higher-level combinatorial process that had been predictively instantiated. Alternatively, they may reflect prolonged attempts to integrate or assimilate unpredicted items that fit with the context to some degree.

Evidence for the latter possibility comes from a recent ERP study by Federmeier and colleagues (2010), who presented contexts consisting of short phrases that predicted a target of a certain category (e.g. A type of insect). The targets could be highly typical (ant), less typical (hornet), or incongruent (gate). Relative to the predicted, highly typical ending, Federmeier et al. observed a frontal positivity for the less typical endings but not the incongruous endings. This suggests that frontal positivities may not index a process associated with the violation of a prediction per se, but rather may reflect processes involved in integrating or assimilating unpredicted, but plausible, items that fit with the context.5

Together, these data provide a possible explanation for the current results: in our study, the unpredicted targets were always completely unrelated to the prime context, and therefore could not be semantically ‘assimilated’ or integrated with the context in any way. On this account, the frontal positivity observed by Holcomb (1988) in a similar paradigm may be due to one particular aspect of the procedure, in which participants were explicitly instructed prior to the high proportion block to attend to the semantic relationship between primes and targets. This may have encouraged participants to attempt to integrate unrelated primes and targets even when their initial prediction was unfulfilled.