Abstract

Hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress has been concerned in the development of diabetic nephropathy (DN), which may cause kidney damage associated with inflammation and fibrosis. This study has been conducted to investigate the role of genistein supplementation in an acute DN state. Mice with FBG levels more than 250 mg/dL after alloxan injection (single i.p., 150 mg/kg) were considered as diabetic. Diabetic mice (DM) were further subdivided according to their FBG levels, medium-high FBG (DMMH < 450 mg/dL) and high FBG (DMH; 450 mg/dL) and were administrated by an AIG-93G diet supplemented with different doses of genistein (0, 0.025 or 0.1%). After 2 weeks' treatment, the levels of kidney malondialdehyde (MDA), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and plasma creatinine and lipid profiles, as well as oxidative stress and inflammation-related markers, were measured (P < 0.05). Genistein supplementation improved levels of FBG in the DMMH groups, but not in the DMH group, regardless of the treatment dose. Moreover, the supplementation attenuated kidney oxidative stress indicated by MDA, BUN, and plasma creatinine. In addition, genistein treatment decreased inflammatory markers such as nuclear factor kappa B (p65), phosphorylated inhibitory kappa B alpha, C-reactive protein, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, cyclooxygenase-2, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha and improved oxidative stress markers (nuclear-related factor E2, heme oxygenase-1, glutathione peroxidase, and superoxide dismutase isoforms) in treatment groups, regardless of the genistein treatment dose. Furthermore, genistein supplementation inhibited the fibrosis-related markers (protein kinase C, protein kinase C-beta II, and transforming growth factor-beta I) in the DN state. However, 0.1% genistein supplementation in diabetes with high FBG levels selectively showed a preventive effect on kidney damage. These results suggest that genistein might be a good protective substance for DN through regulation of oxidative stress and inflammation. In particular, genistein is more efficient in diabetes patients with medium-high blood glucose levels. Finally, it is required to establish the beneficial dosage of genistein according to blood glucose levels.

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a major endocrine-metabolic disorder that is associated with chronic hyperglycemia by disturbance in carbohydrate, protein, and lipid metabolism. According to the WHO (World Health Organization), the world prevalence of diabetes has been increasing explosively from 171 million in 2000 to an assumed 366 million in 2030 [1]. As DM have severe health consequences, it gives rise to diabetic complications including retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy. About 20%–40% of diabetic patients suffer from diabetic nephropathy (DN), which is characterized by end-stage renal disease [2]. DN has been implicated in several mechanisms by hyperglycemia, which may simulate overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS play a crucial role in generation of oxidative stress and several inflammatory responses [3, 4] that trigger cellular dysfunction and progression of kidney fibrosis. Indeed, the response may be upregulated by ROS-related activation of transcription factors and their downstream genes. This fact suggests that the mechanism of several transcription factors is implicated in hyperglycemia-mediated expression of genes involved in DN [5]. Recently, it has become increasingly acknowledged that NFκB generally works with other transcription factors [6, 7], such as nuclear related factor E2 (Nrf2) [8]. DN condition is expected to bring out diverse synergistic effects at the transcriptional level [6]. NFκB induced by oxidative stress is one of the most critical transcriptional regulatory factors that control the expression of a large number of genes involved in inflammatory response, including cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and adhesion molecules [9]. It mediates damages in extracellular matrix, glomerulosclerosis, and renal failure, thus stimulating the development of DN. Recently, an increase in NFκB activation has been observed in DM patients [10, 11] and in DN animals [12]. In contrast to the inflammatory action of NFκB, Nrf2 is responsible for the defense system against oxidative stress [13, 14] and inflammation [8] by regulation of phase II detoxifying enzymes and redox-related antioxidant proteins [15]. It is known that activation of Nrf2 and upregulation of its downstream antioxidant genes in hyperglycemic condition were found not only in the cultured cells, but in DN patients [16]. Therefore, Nrf2 may contribute to the improvement of inflammatory conditions such as DN.

With the onset of ROS production in diabetic kidneys, fibrosis is stimulated by increases in oxidative stress and inflammation. Protein kinase C (PKC) is associated with phosphorylation of serine/threonine residues in insulin receptors and is generated due to the synthesis of diacylglycerol (DAG) under the high intracellular concentration of glucose [17, 18]. In particular, PKC-βII, as one of the various isoforms of PKC, is well known to accelerate the pathogenesis of hyperglycemic kidney injuries, and it leads to insulin resistance as well as to dysfunction of various cells through the reduction of insulin receptor substrate- (IRS-) 2 tyrosine phosphorylation, resulting in defected insulin stimulation and intracellular accumulation of diacylglycerol in various organs [19, 20]. Thus, excessive production of PKC-βII in diabetic kidneys may induce formation of advanced glycation end products (AGE), as well as production of growth factors, such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [21, 22].

Genistein, a class of phytoestrogens known as isoflavones, is mostly found in legumes. It has attracted attention because of its beneficial effects on prevention of metabolic disorders related to cardiovascular disease (CVD), obesity, cancer, and diabetes [23–26]. Thus, genistein has been extensively established as a multifunctional agent through enhancing the antioxidant defense system and anti-inflammation response. Recently, a study focused on the protective role of genistein on renal malfunction in rats fed a fructose rich diet, through the modulation of insulin resistance-induced pathological pathways [27]. Furthermore, Yuan et al. have noted that high doses of genistein (≥5 μmol·L−1) protected renal mesangial cells against a hyperglycemic condition, which increased fibrosis through induction of fibrosis related genes, such as extracellular matrix (ECM) and TGF-β [28]. Another study has shown that genistein injections (10 mg/kg via i.p.) reduced urinary TBARs excretion and renal gp91phox expression, as well as decreased production of inflammatory markers, including p-ERK, ICAM-1, and MCP-1, in DN mice [29]. However, the efficacy of genistein on the connection of complex responses associated with oxidative stress and inflammation in DN is very uncertain. Moreover, little research has focused on the role of genistein in the development of DN in accordance with the degree of fasting blood glucose levels. In this study, we hypothesized that short-term genistein supplementation protects against diabetic kidney damage, depending on fasting blood glucose levels, through enhancement of hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis in DN.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

5.5-week-old female ICR mice were obtained from Daehan Biolink Co., LTD (Eumseong, Choungcheongbuk-do, Republic of Korea). Mice were individually housed in cages and acclimated for a week in animal facility conditions (22 ± 1°C and 50 ± 1% humidity with a 12 h in the light/dark). Diabetes was induced with a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 150 mg/kg alloxan monohydrate (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA) in saline. On the other hand, nondiabetic control mice were injected with only saline in the same manner as the diabetic mice were treated. After a 1-week treatment, the induction of diabetes was confirmed by measuring fasting blood glucose levels. Fasting blood glucose levels from the mouse tail vein were measured by using a one-touch blood glucose meter (LifeScan Inc., Milpitas, USA). Fasting blood glucose levels ≥250 mg/dL were considered as diabetes. All mice care and experiments were approved by the Animal Care Institutional Committee of Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

2.2. Experimental Design

Diabetic mice were subdivided into two groups in accordance with fasting blood glucose (FBG) levels: medium high FBG (DMMH; 250 mg/dL ≤ FBG levels ≤ 450 mg/dL) and high FBG (DMH; 450 mg/dL ≤ FBG levels ≤ 600 mg/dL). Mice were treated with different diets and divided into the following groups (n = 9-10 per group): non-diabetic mice (CON) and diabetic-control mice (DMC; DMMH-C, DMH-C) mice were fed an AIN-93G diet without genistein supplementation (0%). DM-0.025% (0.025% genistein; DMMH-0.025%, DMH-0.025%) mice were fed 0.025% genistein (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA) supplementation. DM-0.1% (0.1% genistein; DMMH-0.1%, DMH-0.1%) mice were fed 0.1% genistein supplementation. More details are shown in Table 1. At the end of the treatment (2 weeks), body weight, food consumption, and fasting blood glucose levels were measured once a week. Mice were fasted 8 h and anesthetized with isoflurane. Blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture, and then they were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The kidneys were washed in saline and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. All samples were stored at −80°C until subsequent analysis.

Table 1.

Classification of experimental groups.

| Group | Treatment |

|---|---|

| CON | Nondiabetic mice were fed AIN-93G diet without genistein supplementation |

| DMMH-C | Diabetic-control mice with the level of medium-high FBG between 250 and 450 were fed AIN-93G diet without genistein supplementation |

| DMMH-0.025% | Diabetic mice with medium high FBG levels between 250 and 450 were fed 0.025% genistein supplementation |

| DMMH-0.1% | Diabetic mice with medium high FBG levels between 250 and 450 were fed 0.1% genistein supplementation |

| DMH-C | Diabetic-control mice with the level of high FBG between 450 and 600 did not receive genistein supplementation |

| DMH-0.025% | Diabetic mice with high FBG levels between 450 and 600 were fed 0.025% genistein supplementation |

| DMH-0.1% | Diabetic mice with high FBG levels between 450 and 600 were fed 0.1% genistein supplementation |

2.3. Measurement of Serum Biochemical Analysis (Lipid Profile)

Blood samples were collected in heparin pretreated-tubes and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min to obtain plasma. The concentrations of total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol in plasma were assayed using the enzymatic method. Briefly, 20 μL of plasma was mixed with an enzymatic kit (Bio-Clinical System, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea) and incubated at 37°C water bath for 10 min. Concentrations were determined at 505 nm, 550 nm, and 500 nm, respectively.

The atherogenic index (AI) of plasma was calculated by the following ratio: (TC/HDL-C)/HDL-C.

2.4. Renal Function Monitoring

2.4.1. Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) Measurement

Kidney function was measured by BUN. Specimens were examined by a commercially available kit (Asan pharmaceutical, Seoul, Republic of Korea) and incubated in a 37°C water bath for 5 min. Then, concentrations were determined at 580 nm using an ELISA reader (BIO-TEK instruments, Winooski, VT, USA).

2.4.2. Plasma Creatinine

Plasma creatinine levels were examined by a creatinine assay kit (Bio-Clinical System, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, a mixture of plasma and picric acid were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. Supernatant was reacted by an NaOH reagent at room temperature for 20 min and determined at 515 nm using an ELISA reader.

2.5. Malondialdehyde (MDA) Measurement in Kidneys

Malondialdehyde (MDA) measurement was usually used for estimation of lipid peroxidation levels [30]. Briefly, kidney homogenates were prepared in 0.15 M KCl buffer. A total of 200 μL of homogenated kidney tissues were mixed with 200 μL of 8.1% SDS and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. A total of 3 mL of 20% acetic acid-0.8% thiobarbituric acid (TBA) mixture (1 : 1, v/v) and 600 μL of distilled water were added to make a total volume of 4 mL. The mixture was heated for 1 h in a 95°C water bath. After cooling in ice water, 1 mL distilled water and a 5 mL mixture of n-butanol and pyridine (15 : 1, v/v) were added to each tube. After centrifuging at 4000 rpm for 10 min, the upper layer was measured at 532 nm using an ELISA reader. Concentrations were determined using a 1,1,3,3-tetramethoxypropane (TMP, sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO., USA) as a standard.

2.6. Preparation of Western Blot

For extraction of whole protein, 0.1 g of kidney tissues was homogenated at 4°C in lysis buffer (containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH7.5, 1% NP40, 0.5% Na-deoxycholate stock, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS) with a protease inhibitor (Sigma Aldrich) and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 30 min. The resulting supernatants were frozen at 80°C until western blot analysis. Nuclear extracts were prepared from 0.25 g of kidney tissue and homogenated in 5 mL of buffer A (0.6% NP40, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES (pH7.9), 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM PMSF, Leupeptin, Pepstatin, and Aprotinin). After centrifugation (2,000 rpm, 4°C, 30 sec), the supernatants incubated on ice for 5 min, centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 5 min, and discarded the supernatant. 200 μL of buffer B (25% Glycerol, 20 mM HEPES (pH7.9), 420 mM NaCl, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.5 mM PMSF, Benzamidine, Leupeptin, Pepstatin, and Aprotinine) was added to the resulting pellet and shacked on ice for 20 min. The resulting suspensions were frozen at 80°C until western blot analysis. Protein concentration was measured using the NanoPhotometer (Implen, Germany). For gel electrophoresis, an equal amount of cytosolic and nuclear protein extracts (50 μg and 25 μg of total protein) was loaded in each lane. Proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and then transferred to the PVDF membrane (Millipore, Marlborogh, MA, USA). The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk or 3% BSA in PBS containing Tween 20 (PBST) and probed overnight at refrigeration temperature with primary antibodies against Nrf2 (dilution 1 : 1000; Abcam), HO-1 (dilution 1 : 1000; Stressgen), GPx (dilution 1 : 16000; Abcam), CuZnSOD (dilution 1 : 1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), MnSOD (dilution 1 : 1000; Stressgen), p65 (dilution 1 : 200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), pIκBα (dilution 1 : 200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), TNF-α (dilution 1 : 200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), CRP (dilution 1 : 200; Abcam), MCP-1(dilution 1 : 1000; Cell Signaling), COX-2 (dilution 1 : 200; Stressgen), PKC (dilution 1 : 200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), PKC-βII (dilution 1 : 200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), TGF-β1 (dilution 1 : 200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and β-actin (dilution 1 : 1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The membrane was washed with PBST and incubated with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA) for 1 h. The target proteins were detected and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence western blotting agents (Elpis Biotech, Republic of Korea) on an Image Analyzer (G box, Syngene, UK). The quantitation of each protein expression compared to the β-actin protein expression level was performed.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SD. Sample normality was tested for primary outcomes (body weight, food intake, and fating blood glucose level). Statistical differences of variables (body weight, food intake, and fasting blood glucose level) between CON and DMH-C were analyzed by unpaired t-test. The effects of DM severity (normal control, DMMH, and DMH) and/or genistein supplemented diet (0, 0.025, and 0.1%) were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Two-way ANOVA was used to analyze the effects of the genistein supplemented diet and DM severity and their interaction on outcomes followed by post hoc test (Tukey HSD) using SPSS (20.0 K for Windows) statistical analysis program. For all outcomes, a value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

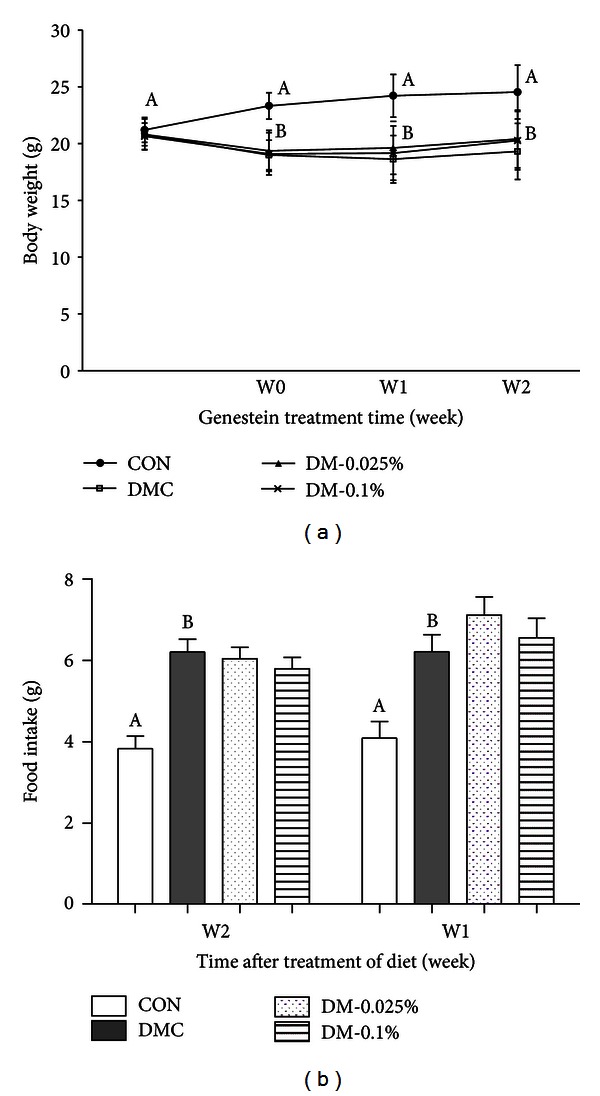

3.1. Effect of Genistein Supplementation on Body Weight and Food Intake

Changes in body weight and food intake during the experimental period are shown in Figure 1. After 1 week of alloxan injection to induce diabetes, body weight in diabetic mice was significantly lower than that of CON (Figure 1(a)). However, genistein supplementation, regardless of dose, did not prevent the decrease in body weight. Food intake was significantly increased in diabetic mice, regardless of genistein supplementation compared with the CON group (Figure 1(b)).

Figure 1.

Effect of genistein supplementation on body weight (a) and food intake (b) in experimental mice. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 9-10/group). Mean values with different letters were significantly different, P < 0.05. Statistical differences of variables between CON and DMH-C analyzed by unpaired t-test were shown in capital letters. CON, control mice; DMC, diabetic control mice; DM-0.025%, diabetic mice supplemented with 0.025% genistein; DM-0.1%, diabetic mice supplemented with 0.1% genistein.

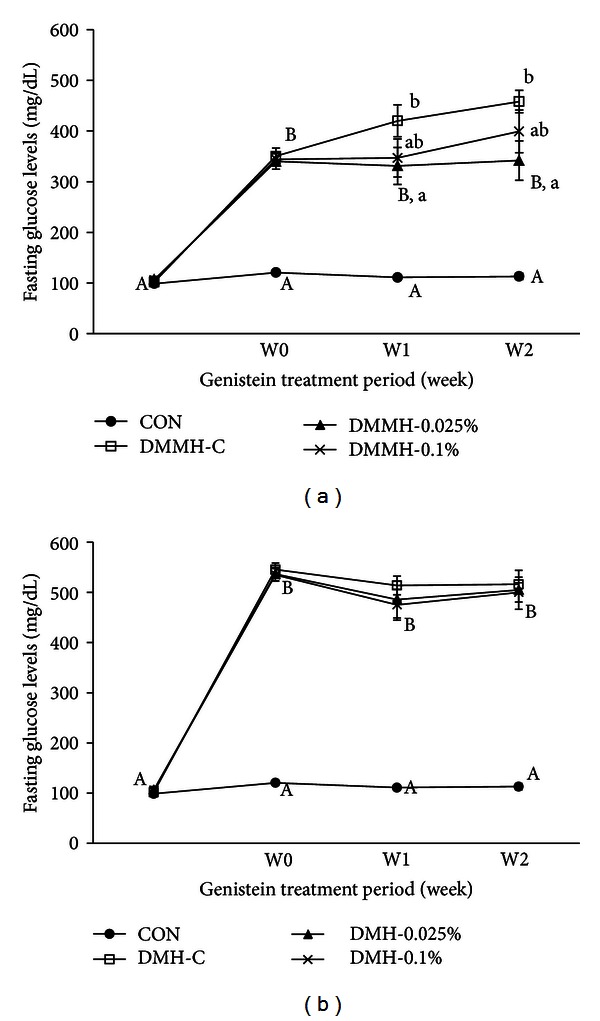

3.2. Effect of Genistein Supplementation on Changes in Fasting Glucose Level

Levels of fasting blood glucose were significantly higher in all the diabetic groups compared to the CON group. The 0.025% genistein supplementation in DMMH significantly decreased FBG levels, but 0.1% genistein in DMMH did not significantly reduce FBG levels (Figure 2(a)). In Figure 2(b), genistein supplementation in DMH did not show a difference in FBG levels.

Figure 2.

Effect of genistein supplementation on fasting blood glucose levels in experimental mice. Fasting blood glucose levels in DMMH group (a) and fasting blood glucose levels in DMH group (b). Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 9-10/group). Mean values with different letters were significantly different, P < 0.05. Statistical differences of variables between CON and DMH-C analyzed by unpaired t-test were shown in capital letters and effects of the genistein supplemented diets on body weight and food intake in diabetic mice using one-way ANOVA was represented by small letters.

3.3. Effect of Genistein Supplementation on Biochemical Markers

3.3.1. Lipid Profiles

To examine the effect of genistein supplementation on lipid profiles, we measured plasma lipid profiles. As shown in Table 2(a), plasma levels of total cholesterol (TC) and triglycerides (TG) were elevated in the DMC more than in the CON, but there were no significant differences between the DMC groups and genistein supplementation groups. Moreover, the plasma level of high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) did not differ among the groups. Thus, the DMC groups were characterized by a markedly elevated atherogenic index (AI) as compared to the CON group, but genistein supplementation did not effectively decrease AI.

Table 2.

Effect of genistein supplementation on biochemical markers.

| Group | Lipid profiles | Kidney function | Oxidative stress | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC (mg/dL) |

TG (mg/dL) |

HDL-C (mg/dL) |

AI | BUN (mg/dL) |

Creatinine (mg/dL) |

MDA (nM) |

|

| CON | 121.72 ± 12.83A | 87.03 ± 19.35A | 77.74 ± 13.45 | 0.57 ± 0.23A | 17.76 ± 3.04A | 0.57 ± 0.08A | 16.87 ± 4.28A |

| DMMH-C | 187.98 ± 21.15B | 119.89 ± 26.92AB | 70.24 ± 11.61 | 0.97 ± 0.2B | 46.99 ± 21.49BCb | 0.81 ± 0.13Bb | 25.82 ± 6.23Bb |

| DMMH-0.025% | 171.65 ± 21.47 | 96.19 ± 22.39 | 75.93 ± 5.62 | 0.80 ± 0.14 | 24.93 ± 10.99a | 0.62 ± 0.10a | 17.23 ± 3.01a |

| DMMH-0.1% | 178.56 ± 39.68 | 109.65 ± 14.96 | 73.81 ± 5.36 | 0.88 ± 0.24 | 26.78 ± 5.56a | 0.64 ± 0.09a | 17.65 ± 2.97a |

| DMH-C | 206.64 ± 43.56B | 132.21 ± 20.88B | 64.05 ± 8.78 | 0.98 ± 0.22B | 67.35 ± 58.51Cb | 0.94 ± 0.25Cc | 25.90 ± 3.57Bb |

| DMH-0.025% | 172.29 ± 45.89 | 107.71 ± 29.20 | 73.83 ± 15.64 | 0.93 ± 0.23 | 32.30 ± 10.68a | 0.72 ± 0.11ab | 18.33 ± 5.26a |

| DMH-0.1% | 173.32 ± 46.33 | 121.43 ± 35.15 | 71.10 ± 29.38 | 0.94 ± 0.41 | 32.78 ± 7.95a | 0.79 ± 0.21bc | 20.04 ± 4.94ab |

Abbreviations: TC: total cholesterol, TG: triglyceride, HDL: high density lipoprotein cholesterol, AI: atherogenic index, BUN: blood urea nitrogen, and MDA: malondialdehyde.

Mean values with different letters were significantly different (P < 0.05). Statistical differences of variables among CON, DMMH-C, and DMH-C analyzed by one-way ANOVA were shown in capital letters and effects of the genistein supplemented diet and/or DM severity using two-way ANOVA were represented by small letters.

3.3.2. Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN)

As shown in Table 2(b), the concentration of BUN was significantly increased in the DMMH-C and DMH-C groups compared to that of the CON group (P < 0.05). BUN concentrations of 0.025% DMMH and 0.1% DMMH were decreased by 47% and 43%, respectively, as compared to the DMMH-C group, BUN concentrations of 0.025% DMH and 0.1% DMH groups were significantly decreased by 52% and 51%, respectively, as compared to the DMH-C group.

3.3.3. Plasma Creatinine

As shown in Table 2(c), plasma creatinine levels were significantly elevated in the DMMH-C and the DMH-C groups compared with the CON group (P < 0.05). The concentration of plasma creatinine was much higher in the DMH-C group than in the DMMH-C group. Genistein supplementation, regardless of dose, in the DMMH group ameliorated plasma creatinine levels. However, although the plasma creatinine level of the DMH group reached more than 1.5-fold compared to the CON group, only the 0.025% genistein supplementation significantly decreased plasma creatinine levels in DMH.

3.3.4. MDA

To examine the effect of genistein supplementation on oxidative stress in kidneys, kidney MDA levels were measured. MDA levels were significantly elevated in both the DMMH-C and DMH-C groups (1.5-fold above CON, P < 0.05). On the other hand, genistein supplementation in the DMMH-C groups reduced the level of MDA concentration to the normal level. The supplementation of 0.025% genistein significantly decreased the kidney MDA levels (DMMH-L; 33.26%, DMH-H; 29.22% compared to DMC), but the supplementation of 0.1% genistein did not significantly reduce it in the DMH mice (Table 2(d)).

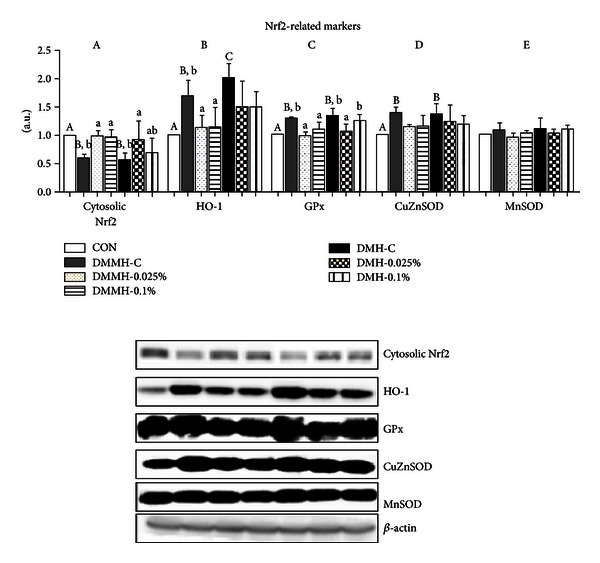

3.4. Effect of Genistein on Protein Expression Levels of Oxidative Stress Markers in Diabetic Kidneys

We performed western blot analysis to determine whether genistein supplementation declined the activation of Nrf2-linked oxidative stress proteins in DN. The levels of cytosolic Nrf2 protein expression decreased in the DMMH-C and DMH-C groups (P < 0.05, Figure 3(a)). We found that the reduction of cytosolic Nrf2 protein levels in DMMH was effectively restored by genistein supplementation regardless of dose. The 0.025% genistein supplementation in DMH significantly raised the cytosolic Nrf2 levels, more than the DMH-C (P < 0.05), but 0.1% genistein in DMH did not significantly affect cytosolic Nrf2 expression. The expression of HO-1 levels, a representative target gene in the Nrf2 pathway, was significantly increased in the DMC as compared with the CON (P < 0.05). In addition, the expression of HO-1 was much higher in the DMC-C group than in the DMMH-C group. Genistein supplementation, regardless of dose, completely reduced the expression of HO-1 levels in DMMH and DMH (Figure 3(b)). Furthermore, GPx levels were significantly increased in DMC mice, more so than in CON mice (Figure 3(c)). GPx expression in the DMMH group was normalized by genistein supplementation independently of the dose. In the DMH group, 0.025% genistein supplementation significantly reduced GPx expression, while 0.1% genistein supplementation was not changed. As shown in Figure 3(d), the expression of CuZnSOD levels was higher in the DMMH-C and the DMH-C than in the CON. Genistein supplementation relatively decreased the CuZnSOD levels, although the difference was not statistically significant. Unfortunately, the expression of MnSOD levels did not significantly differ among the groups (Figure 3(e)).

Figure 3.

Effect of genistein supplementation on the kidney protein levels of cytosolic Nrf2 (a), HO-1 (b), GPx (c), CuZnSOD (d), and MnSOD (e) in experimental mice. All results were conducted at least three times. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 9-10/group). Mean values with different letters were significantly different, P < 0.05. Statistical differences of variables among CON, DMMH-C, and DMH-C analyzed by one-way ANOVA were shown in capital letters and effects of the genistein supplemented diet and/or DM severity using two-way ANOVA were represented by small letters.

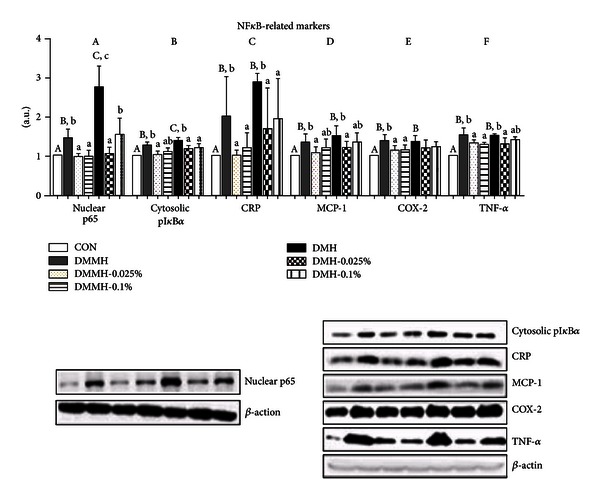

3.5. Effect of Genistein on Protein Expression Levels of Inflammation Markers in Diabetic Kidneys

We tested to elucidate whether the genistein supplementation reduced the expression of NFκB-related inflammatory proteins in DN. The levels of NFκB (p65) and pIκBα, an indirect marker for measuring the activation of NFκB, were significantly increased in the DMC as compared to the CON (Figures 4(a) and 4(b)). Genistein supplementation, regardless of dose, significantly decreased the levels of cytosolic pIκBα and nuclear NFκB in DMMH and DMH compared to DMMH-C and DMH-C (P < 0.05). Next, we measured the expression of CRP, which was increased by alloxan-induced diabetes (Figure 4(c)). Genistein supplementation, regardless of dose, significantly inhibited increased CRP levels in the DMMH and DMH groups (P < 0.05). As shown in Figure 4(d), MCP-1 levels were higher in DMMH-C and DMMH-C than in CON, and the levels in DMMH and DMH were markedly lower by 0.025% genistein. However, 0.1% genistein showed no significant inhibitory effects on the MCP-1 levels in DMMH and DMH. The protein expression of COX-2, as a representative marker of the NFκB-pathway, was significantly elevated in DMC (P < 0.05). Genistein supplementation in DMMH suppressed the upregulation of COX-2 levels, while there was no difference in the DMH groups (Figure 4(e)). Additionally, TNF-α levels were significantly higher in all diabetic mice than in CON mice (Figure 5(f)). However, the genistein supplementation groups exhibited a remarkable reduction in the expression of TNF-α in comparison with the DMC groups, excluding DMH-0.1% (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effect of genistein supplementation on the kidney protein levels of p65 (NFκB) (a), pIκBα (b), CRP (c), MCP-1 (d), COX-2 (e), and TNF-α (f) in experimental mice. All results were conducted at least three times. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 9-10/group). Mean values with different letters were significantly different, P < 0.05. Statistical differences of variables among CON, DMMH-C, and DMH-C analyzed by one-way ANOVA were shown in capital letters and effects of the genistein supplemented diet and/or DM severity using two-way ANOVA were represented by small letters.

Figure 5.

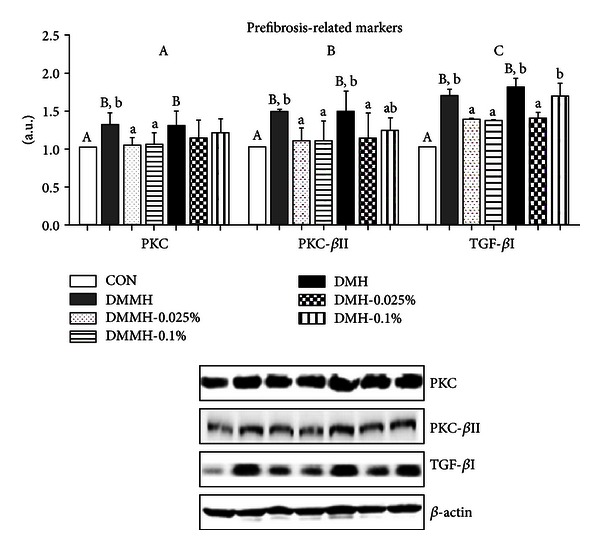

Effect of genistein supplementation on the kidney protein levels of PKC (a), PKC-βII (b), and TFG-βI (c) in experimental mice. All results were conducted at least three times. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 9-10/group). Mean values with different letters were significantly different, P < 0.05. Statistical differences of variables among CON, DMMH-C and DMH-C analyzed by one-way ANOVA were shown in capital letters and effects of the genistein supplemented diet and/or DM severity using two-way ANOVA was represented by small letters.

3.6. Effect of Genistein on Protein Expression Levels of Fibrosis-Mediated Markers in Diabetic Kidneys

We examined the question as to whether genistein supplementation contributed to enhancing an antidiabetic kidney fibrosis pathway in the experimental mice. Our data showed a significant increase in PKC and PKC-βII protein expression in the DMC groups, regardless of FBG levels (Figures 5(a) and 5(b)). The levels of PKC and PKC-βII protein expression in DMMH were effectively decreased by genistein supplementation regardless of dose (P < 0.05). The level of PKC expression in DMH was reduced by genistein supplementation, regardless of dose, but there was not a significant difference (Figure 5(a)). The 0.025% genistein supplementation in DMH was more effective at reducing the level of PKC-βII protein expression than the 0.1% genistein in DMH (Figure 5(b)). To further investigate the mechanism of an antifibrosis effect of genistein, we tested the expression of TFG-βI. TFG-β1, as one of the most potent fibrogenic response markers, was greater in DMC than those of CON. However, as contrasted with nontreated genistein supplementation, genistein supplementation groups experienced significant decreased expression of TFG-βI, except DMH-0.1% (P < 0.05).

4. Discussion

The present study provides some good evidence that genistein has an ability to protect kidneys from hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis in alloxan-induced diabetic mice. Although genistein has beneficial influences with respect to both antioxidative stress and anti-inflammation [31], there is no clear underlying mechanism by which genistein can boost a protective role in DN progression in accordance with blood glucose levels. A severe loss of body weight (B.W.) and an increase of food intake generally occur in diabetic conditions [32–34]. We also examined the question as to whether genistein supplementation did not improve body weight loss and food intake as shown in the previous studies [35, 36].

An ultimate treatment goal of diabetes and its complications is the control of the FBG levels [37]. According to previous studies, a glucose level with 250–450 mg/dL was diagnosed as mild hyperglycemia [38], and a glucose level above 450 mg/dL was considered as severe hyperglycemia [39]. In this study, diabetes with different FBG levels, in a range from 250 mg/dL to 600 mg/dL (maximum read by commercial glucometer), and FBG levels of 450 mg/dL were used as the criteria of hyperglycemia classification. Our data found that genistein supplementation decreased the FBG level in DMMH mice, but it did not affect blood glucose levels in DMH mice. Previously, genistein has been shown to have an effect on the modulation of blood glucose levels in vivo, regardless of the manner of genistein administration and treatment period and dose, which have included short-term (for 16 days) i.p. injection of genistein (1 mg/kg B.W./day) in rats fed a fructose rich diet [27] and long-term (for 9 weeks) dietary supplementation of genistein (0.02% w/w) in nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice [35]. In other findings [40], it was discovered that not a low dose (under 15 mg/kg B.W.) but a high dose (15–30 mg/kg B.W.) of genistein supplementation markedly reduced blood glucose levels in alloxan-induced diabetes mice. However, researchers have not proven a potential benefit of genistein on diabetic animals with different levels of FBG. Collectively, the results suggested that short-term supplementation of genistein possesses the capacity to reduce hyperglycemia in the DMMH group without insulin treatment but not in DMH group.

Impairment of insulin secretion in diabetes increases the release of free fatty acids (FFA) into the liver, and it may cause an increase in triglyceride production [41]. It promotes diabetic dyslipidemia, which may worsen the interplay of inflammation and intrarenal fibrosis [42, 43]. A previous study reported that genistein supplementation (600 mg/kg diet) for 3 weeks improved plasma lipid profiles (TC, TG, and HDL) in diabetic mice [44], whereas another study confirmed that genistein supplementation (250 mg/kg diet) for 4 weeks did not improve the plasma lipid profiles in diabetic mice [45]. Our data showed that genistein supplementation, regardless of supplementation doses (0.025% in a 250 mg/kg diet or 0.1% in a 1000 mg/kg diet), did not show a lowering effect on dyslipidemia. These results suggest that diabetes-related dyslipidemia is controlled by a relatively high concentration of genistein supplementation for longer than 3 weeks of treatment.

BUN and plasma creatinine, as waste products of metabolism, preannounce damage in kidney function [46]. We observed that BUN and plasma creatinine levels were increased in DMC mice, especially in DMH-C. Sung et al. [47] reported that the genistein addition (10 mg/kg B.W.) for 3 days significantly reduced BUN and serum creatinine levels in cisplatin-induced acute renal injury. We also observed that genistein supplementation decreased BUN levels in DMMH group and DMH group. BUN is usually done together with a plasma creatinine, which is a more sensitive marker of kidney damage. Genistein supplementation in DMMH alleviated plasma creatinine levels to normal levels and significantly reduced the levels in DMH-0.025%, but not in DMH-0.1%. Thus, our data demonstrated that genistein, regardless of supplemented dose, could prevent an impairment of kidney function in DMMH, and only the 0.025% genistein supplementation may have beneficial effects on kidney damage when the FBG level is very high.

In diabetic conditions, a continuous overproduction of ROS and an antioxidant defense system may cause mitochondrial impairment [48]. Thus, oxidative stress is considered as a mediator in tissue injury, including liver, brain, and kidney. The kidney is known as a highly sensitive organ in oxidative stress conditions because lipid composition in kidneys comprises long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids [49]. In our experiments, the MDA accumulation was increased by consequences of oxidative stress, such as diabetes [50], but genistein (6 mg/kg/B.W.) decreased the MDA levels in the brain and liver of STZ-induced diabetic mice [51]. Our study also observed that genistein supplementation significantly lowered kidney MDA levels in diabetic mice, except in DMH-0.1%. A previous study demonstrated that a high dose of genistein can have adverse actions as a prooxidant, depending on the status of oxidative stress [52]. Therefore, the results suggest that 0.1% genistein supplementation may act as a prooxidant in the DMH group, which is considered as possessing higher oxidative stress status compared to the DMMH group.

Nrf2 is normally combined with its repressive protein Keap1 (Kelch-like ECH-associated protein-1) in cytoplasm [53]. In an oxidative stress state, Nrf2 is separated from Keap1 and translocated to the nucleus. It activates antioxidant enzymes such as HO-1, GST, NADH(H) quinoline oxidoreductase-1 (NQO1), and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) [54, 55]. Therefore, Nrf2 and its downstream genes play a crucial role in defense of cellular damage against oxidative stress, but its overproduction may lead to paradoxical effects in connection with a disturbance in the protection of cells from oxidative damage [56]. Previous studies reported that expression of Nrf2 and antioxidant genes, such as HO-1, SOD, catalase (CAT), and GPx, was increased in diabetes [57–59]. The results suggest that excessive production of oxidative stress seems to stimulate increases in antioxidant enzyme production in order to eliminate oxidative stress agents in DM. It is known that genistein has cytoprotective effects on Nrf2 activation and its downstream antioxidant enzymes, including HO-1, SOD, CAT, and GSH [60]. Our data showed that cytosolic Nrf2 was decreased in diabetes, which may lead to an increase in nuclear Nrf2 activation as a consequence of the activation of a cellular antioxidant defense with increased transcription of antioxidant genes. The results were reversed by the genistein supplementation, and this outcome supports the hypothesis that genistein supplementation was able to reestablish the cell homeostasis. However, 0.1% genistein in DMH did not markedly change Nrf2 levels. These findings indicate that 0.1% genistein may be not enough to provide beneficial effects on the Nrf2-mediated oxidative stress pathway in diabetic mice with high FBG levels.

HO-1, a representative marker of an Nrf2-related stress response, has been found to increase in pathological conditions such as diabetes [61–63]. The present study demonstrated that genistein supplementation, regardless of dose, tends to reduce the expression of HO-1 levels in DMMH and DMH. Moreover, protein levels of GPx and SOD isoforms are associated with oxidative damage and mitochondrial dysfunction through hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) production by the glucose oxidase system [64–66]. A previous study [67] demonstrated that GPx activity was increased in diabetic mice organs including the liver, pancreas, and kidney. Our findings proved that genistein supplementation reduced GPx levels, except the DMH-0.1% group. However, genistein did not significantly reduce CuZnSOD levels and did not change MnSOD levels among the groups. These results suggest that genistein supplementation selectively alleviated oxidative stress through the regulation of Nrf2 levels and its consequent events. Moreover, the DMH group with a high dose supplementation of genistein may have more oxidative stress.

Nrf2-mediated interplay has two sides of action as either a regulator of antioxidant response or a reactive promoter of oxidative stress in abnormal conditions [68]. On the basis of our results, we proposed that an overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in diabetes can trigger activation of nucleus Nrf2 and transcription of its downstream target enzymes. On the other hand, oxidative stress leads to activation of the inflammatory-mediated transcription factor, NFκB. Thus, we identified the fact that genistein supplementation attenuated the hyperglycemia-induced inflammatory responses through the regulation of the NFκB pathway. Many studies have reported experimental evidence showing that NFκB was activated in diabetic kidneys [69, 70], and genistein supplementation (1 mg/kg/B.W.) attenuates NFκB (P65) activation in kidneys of rats fed a fructose rich diet [71]. We have investigated the pIκBα level in cytosol and NFκB (p65) level in nucleus to identify NFκB activation. pIκBα level is a representative of NFκB activation in cytosol because pIκBα after phosphorylation of IκBα is subsequently ubiquitinated and degraded via the proteasome pathway [72]. NFκB, p65 and p50 heterodimer, separated from IκBα is translocated into the nucleus and activates the expression of inflammatory genes. Our data showed that the protein levels of pIκBα in cytosol and NFκB in nucleus as increased in DMC and lowered in genistein supplementation. These results imply that genistein supplementation blocked NFκB activation by reduction of pIκBα.

Activation of the NFκB signaling pathway is known to enhance inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α) and activate fibrosis markers (AGE, RAGE) in diabetic mice [73]. Among them, TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor-α) is the main proinflammatory cytokine, which acts toward the progression of diabetic kidney disease through recruitment of macrophages and neutrophils into the kidney [74]. An increased renal TNF-α level is correlated with indicators of renal failure in DM animals [75] and patients [76]. The present study confirmed that TNF-α levels in genistein supplementation groups were even lower than those in DMC groups. However, DMH with 0.1% genistein did not show significant differences, which means that 0.025% genistein is more effective than 0.1% genistein for DN with high FBG levels. CRP is generally increased in inflammatory conditions, such as those found in DN patients and animals [77, 78]. Dietary isoflavone, including genistein, has a capacity to decrease the concentration of CRP in human plasma [79, 80]. Similarly, the expression of CRP levels in DN mice was significantly reduced in all diabetic mice supplemented with genistein, more so than those of DMC. In addition, expression of MCP-1 and COX-2 is relevant to NFκB-mediated modulation of an inflammatory cascade, which contributes to endothelial dysfunction [81–83]. Genistein (10 mg/kg via i.p., three times a week) as a tyrosine kinase inhibitor has been shown to reduce significantly the excretion of urinary MCP-1 in STZ-induced diabetic mice [29]. Our results showed that the production of MCP-1 significantly decreased in the 0.025% genistein supplementation groups, whereas the 0.1% genistein supplementation groups did not reduce MCP-1 production. Thus, the results suggest that a relatively low dose of genistein may reduce MCP-1 protein via inhibition of NFκB activation. Moreover, genistein, as an inhibition agent of cell proliferation, inhibited COX-2 protein in cancer cells [84], a result that improved the balance of angiogenesis and apoptosis. In our findings, overproduction of COX-2 in DMMH was attenuated by genistein supplementation at both 0.025% and 0.1% levels, but not in DMH. In other words, 0.025% genistein supplementation in diabetes with medium high FBG may control vascular homeostasis through suppression of NFκB-mediated inflammation.

Moreover, the findings indicate that Nrf2 activation and its downstream signalling pathway interact with the activation of NFκB-mediated inflammatory responses in diabetes, and genistein supplementation might reduce activation of antioxidant defence systems and inflammatory responses by regulation of Nrf2 and NFκB interactions.

Nrf2 and NFκB interactions may play a serious role in fibrosis in diabetic kidneys, which corresponds with increased PKC-mediated pathways in hyperglycemic conditions. This conclusion has been supported by several in vitro experiments [85], which demonstrated that genistein (40 μM) blocked PKC activation in VEGF-stimulated endothelial cells [86]. However, there is no research focusing on the effect of genistein on PKC inhibition in diabetic animals. The PKC-β isoform is mainly responsible for hyperglycemia-induced fibrosis in DN [87]. Several reports have provided evidence that genistein attenuated the levels of PKC isoenzymes, such as PKC-βI, in rat ventricular monocytes [88], as well as levels of PKC-βII in rats fed a fructose rich diet, an experiment that constitutes a hypertension mouse model [89]. Our data showed the different effects of genistein on prefibrosis-related markers, both PKC and PKC-βII, in DMH depending on their treatment dose. The 0.1% genistein supplementation in the DMH group did not significantly reduce the levels of both PKC and PKC-βII. This result suggests that 0.1% genistein supplementation may not have beneficial effects on fibrosis in diabetes with high FBG. Continuous exposure of ROS in hyperglycemia may also lead to changes in cell membrane structure. The transforming growth factor βI (TFG-βI), a family of fibrogenic cytokine, has been generally known to induce deposition of matrix components, such as ECM, as well as synthesis of glomerulosclerosis in DN rats [90]. A hyperglycemic condition induces an increase in TGF-βI levels, and it stimulates fibrosis of numerous organs, such as the kidney [91]. Thus, inhibition of TGF- βI is a key player in protection of diabetic kidneys. Genistein has been proven effective in the prevention of hyperglycemia-induced fibrosis by inhibiting the expression of TGF- βI [28] and TGF- βII [92]. In particular, the data showed that genistein was able to inhibit TGF-βI production, not at a low concentration (≤5 μmol·L−1), but at a high concentration (≥5 μmol·L−1) [28], and to reduce TGF-βII production at the high concentration level (5 μg/mL) [92]. However, our results demonstrated that 0.1% genistein supplementation did not protect against the fibrosis process, represented by TGF-βII, from a severe hyperglycemic condition in DMH. The results might be associated with the prooxidant effect of genistein at high doses on severe hyperglycemia as a promotor of prefibrosis in DN.

Taken together, our data evidenced that genistein supplementation inhibited hyperglycemia-induced fibrosis pathways as well as the activation of the transcription factors, Nrf2 and NFκB. Moreover, we found that genistein supplementation has selective effects on diabetic kidney damage in accordance with FBG levels. In previous studies, genistein has been shown to have adverse effects in pathogenetic conditions, which may act as prooxidants and accelerate the progression of disease [93]. However, this study has several limitations. Only the short-term effects of dietary genistein supplementation have been investigated with respect to diabetes induced kidney damage. Long-term supplementation protocols may be helpful to verify the role of genistein in the DMH group (>450 mg/dL) because the DMH group may need a longer time to control inflammation, oxidative stress, and fibrosis processes. Moreover, short-term supplementation at different doses did not change plasma lipid profiles. This result might be associated with supplemented doses and periods, as well as FBG levels. In addition to treatment regimens, histological analysis of kidneys may be more helpful to investigate fibrosis process in this study.

In conclusion, understanding the molecular mechanisms that regulate oxidative stress, inflammation and fibrosis is critical not only in diabetic kidney damage, but also in other diabetic complications. Hence, the results of this study may provide critical insight into future nutritional intervention strategies, with or without insulin treatment, designed to prevent diabetic complications according to FBG levels.

Conflict of Interests

The authors and manufacturers disclose no actual potential conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2012-R1A1A2040217).

Abbreviations

- DN:

Diabetic nephropathy

- FBG:

Fasting blood glucose

- ROS:

Reactive oxygen species

- BUN:

Blood urea nitrogen

- NFκB:

Nuclear factor kappa B

- Nrf2:

Nuclear related factor E2

- HO-1:

Heme oxygenase-1

- CRP:

C-reactive protein

- MCP-1:

Monocyte chemotactic protein-1

- COX-2:

Cyclooxygenase-2

- GPx:

Glutathione peroxidase

- MDA:

Malondialdehyde

- CuZnSOD:

Copper zinc superoxide dismutase

- MnSOD:

Manganese superoxide dismutase

- pIκBα:

Phosphorylated inhibitory kappa B alpha

- TNF-α:

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- PKC:

Protein kinase C

- PKC-βII:

Protein kinase C-beta II

- TGF-βI:

Transforming growth factor-beta I.

References

- 1.Setacci C, De Donato G, Setacci F, Chisci E. Diabetic patients: epidemiology and global impact. Journal of Cardiovascular Surgery. 2009;50(3):263–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vallon V, Thomson SC. Renal function in diabetic disease models: the tubular system in the pathophysiology of the diabetic kidney. Annual Review of Physiology. 2012;74:351–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maritim AC, Sanders RA, Watkins JB., III Diabetes, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: a review. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology. 2003;17(1):24–38. doi: 10.1002/jbt.10058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ponugoti B, Dong G, Graves DT. Role of forkhead transcription factors in diabetes-induced oxidative stress. Experimental Diabetes Research. 2012;2012:7 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/939751.939751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanchez AP, Sharma K. Transcription factors in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine. 2009;11, article e13 doi: 10.1017/S1462399409001057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmid H, Boucherot A, Yasuda Y, et al. Modular activation of nuclear factor-κB transcriptional programs in human diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2006;55(11):2993–3003. doi: 10.2337/db06-0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valen G, Yan ZQ, Hansson GK. Nuclear factor kappa-B and the heart. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2001;38(2):307–314. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedruzzi LM, Stockler-Pinto MB, Leite M, Jr., Mafra D. Nrf2-keap1 system versus NF-κB: the good and the evil in chronic kidney disease? Biochimie. 2012;94(12):2461–2466. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghosh S, Hayden MS. New regulators of NF-kappaB in inflammation. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2008;8(11):837–848. doi: 10.1038/nri2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nam JS, Cho MH, Lee GT, et al. The activation of NF-κB and AP-1 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from patients with diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2008;81(1):25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mezzano S, Aros C, Droguett A, et al. NF-κB activation and overexpression of regulated genes in human diabetic nephropathy. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2004;19(10):2505–2512. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen L, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Wang B. Improvement of inflammatory responses associated with NF-κB pathway in kidneys from diabetic rats. Inflammation Research. 2008;57(5):199–204. doi: 10.1007/s00011-006-6190-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng H, Whitman SA, Wu W, et al. Therapeutic potential of Nrf2 activators in streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2011;60(11):3055–3066. doi: 10.2337/db11-0807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vomhof-Dekrey EE, Picklo MJ., Sr. The Nrf2-antioxidant response element pathway: a target for regulating energy metabolism. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2012;23(10):1201–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim HJ, Vaziri ND. Contribution of impaired Nrf2-Keap1 pathway to oxidative stress and inflammation in chronic renal failure. American Journal of Physiology. 2010;298(3):F662–F671. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00421.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang T, Huang Z, Lin Y, Zhang Z, Fang D, Zhang DD. The protective role of Nrf2 in streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2010;59(4):850–860. doi: 10.2337/db09-1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanwar YS, Wada J, Sun L, et al. Diabetic nephropathy: mechanisms of renal disease progression. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2008;233(1):4–11. doi: 10.3181/0705-MR-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ayo SH, Radnik R, Garoni JA, Troyer DA, Kreisberg JI. High glucose increases diacylglycerol mass and activates protein kinase C in mesangial cell culture. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;261(4, part 2):F571–F577. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1991.261.4.F571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sobhia ME, Grewal BK, Bhat J, Rohit S, Punia V. Protein kinase C βII in diabetic complications: survey of structural, biological and computational studies. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 2012;16(3):325–344. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2012.667804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morino K, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance in humans and their potential links with mitochondrial dysfunction. Diabetes. 2006;55(2):S9–S15. doi: 10.2337/db06-S002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ikeda A, Matsushita S, Sakakibara Y. Inhibition of protein kinase C β ameliorates impaired angiogenesis in type I diabetic mice complicating myocardial infarction. Circulation Journal. 2012;76(4):943–949. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-0881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meier M, Park JK, Overheu D, et al. Deletion of protein kinase C-β isoform in vivo reduces renal hypertrophy but not albuminuria in the streptozotocin-induced diabetic mouse model. Diabetes. 2007;56(2):346–354. doi: 10.2337/db06-0891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gencel VB, Benjamin MM, Bahou SN, Khalil RA. Vascular effects of phytoestrogens and alternative menopausal hormone therapy in cardiovascular disease. Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 2012;12(2):149–174. doi: 10.2174/138955712798995020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stephenson TJ, Setchell KDR, Kendall CWC, Jenkins DJA, Anderson JW, Fanti P. Effect of soy protein-rich diet on renal function in young adults with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Clinical Nephrology. 2005;64(1):1–11. doi: 10.5414/cnp64001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orgaard A, Jensen L. The effects of soy isoflavones on obesity. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2008;233(9):1066–1080. doi: 10.3181/0712-MR-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pavese JM, Farmer RL, Bergan RC. Inhibition of cancer cell invasion and metastasis by genistein. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2010;29(3):465–482. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9238-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palanisamy N, Viswanathan P, Anuradha CV. Effect of genistein, a soy isof lavone, on whole body insulin sensitivity and renal damage induced by a high-fructose diet. Renal Failure. 2008;30(6):645–654. doi: 10.1080/08860220802134532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuan WJ, Jia FY, Meng JZ. Effects of genistein on secretion of extracellular matrix components and transforming growth factor beta in high-glucose-cultured rat mesangial cells. Journal of Artificial Organs. 2009;12(4):242–246. doi: 10.1007/s10047-009-0479-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elmarakby AA, Ibrahim AS, Faulkner J, Mozaffari MS, Liou GI, Abdelsayed R. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor, genistein, reduces renal inflammation and injury in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Vascular Pharmacology. 2011;55(5-6):149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levitan I, Volkov S, Subbaiah PV. Oxidized LDL: diversity, patterns of recognition, and pathophysiology. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2010;13(1):39–75. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valsecchi AE, Franchi S, Panerai AE, Sacerdote P, Trovato AE, Colleoni M. Genistein, a natural phytoestrogen from soy, relieves neuropathic pain following chronic constriction sciatic nerve injury in mice: Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2008;107(1):230–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Shamaony L, Al-Khazraji SM, Twaij HAA. Hypoglycaemic effect of Artemisia herba alba. II. Effect of a valuable extract on some blood parameters in diabetic animals. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1994;43(3):167–171. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andallu B, Varadacharyulu NC. Antioxidant role of mulberry (Morus indica L. cv. Anantha) leaves in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2003;338(1-2):3–10. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(03)00322-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pi-Sunyer FX. Weight loss in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(6):1526–1527. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.6.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi MS, Jung UJ, Yeo J, Kim MJ, Lee MK. Genistein and daidzein prevent diabetes onset by elevating insulin level and altering hepatic gluconeogenic and lipogenic enzyme activities in non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews. 2008;24(1):74–81. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Babu PV, Si H, Fu Z, Zhen W, Liu D. Genistein prevents hyperglycemia-induced monocyte adhesion to human aortic endothelial cells through preservation of the cAMP signaling pathway and ameliorates vascular inflammation in obese diabetic mice. Journal of Nutrition. 2012;142(4):724–730. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.152322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamagishi SI, Fukami K, Ueda S, Okuda S. Molecular mechanisms of diabetic nephropathy and its therapeutic intervention. Current Drug Targets. 2007;8(8):952–959. doi: 10.2174/138945007781386884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ventura-Sobrevilla J, Boone-Villa VD, Aguilar CN, et al. Effect of varying dose and administration of streptozotocin on blood sugar in male CD1 mice. Proceedings of the Western Pharmacology Society. 2011;54:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matteucci E, Giampietro O. Proposal open for discussion: defining agreed diagnostic procedures in experimental diabetes research. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2008;115(2):163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang W, Wang S, Li L, Liang Z, Wang L. Genistein reduces hyperglycemia and islet cell loss in a high-dosage manner in rats with alloxan-induced pancreatic damage. Pancreas. 2011;40(3):396–402. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318204e74d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mooradian AD. Dyslipidemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nature Clinical Practice Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2009;5(3):150–159. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cerasola G, Guarneri M, Cottone S. Inflammation, oxidative stress and kidney function in arterial hypertension. Giornale Italiano di Nefrologia. 2009;26:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cottone S, Lorito MC, Riccobene R, et al. Oxidative stress, inflammation and cardiovascular disease in chronic renal failure. Journal of Nephrology. 2008;21(2):175–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee JS. Effects of soy protein and genistein on blood glucose, antioxidant enzyme activities, and lipid profile in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Life Sciences. 2006;79(16):1578–1584. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fu Z, Gilbert ER, Pfeiffer L, Zhang Y, Fu Y, Liu D. Genistein ameliorates hyperglycemia in a mouse model of nongenetic type 2 diabetes. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism. 2012;37(3):480–488. doi: 10.1139/h2012-005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kadkhodaee M, Mikaeili S, Zahmatkesh M, et al. Alteration of renal functional, oxidative stress and inflammatory indices following hepatic ischemia-reperfusion. General Physiology and Biophysics. 2012;31(2):195–202. doi: 10.4149/gpb_2012_024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sung MJ, Kim DH, Jung YJ, et al. Genistein protects the kidney from cisplatin-induced injury. Kidney International. 2008;74(12):1538–1547. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kang J, Pervaiz S. Mitochondria: redox metabolism and dysfunction. Biochemistry Research International. 2012;2012:14 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/896751.896751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ozbek E. Induction of oxidative stress in kidney. International Journal of Nephrology. 2012;2012:9 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/465897.465897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MTD, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2007;39(1):44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Valsecchi AE, Franchi S, Panerai AE, Rossi A, Sacerdote P, Colleoni M. The soy isoflavone genistein reverses oxidative and inflammatory state, neuropathic pain, neurotrophic and vasculature deficits in diabetes mouse model. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2011;650(2-3):694–702. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salvi M, Brunati AM, Clari G, Toninello A. Interaction of genistein with the mitochondrial electron transport chain results in opening of the membrane transition pore. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2002;1556(2-3):187–196. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(02)00361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Motohashi H, Yamamoto M. Nrf2-Keap1 defines a physiologically important stress response mechanism. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2004;10(11):549–557. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang F, Tian F, Whitman SA, et al. Regulation of transforming growth factor beta1-dependent aldose reductase expression by the Nrf2 signal pathway in human mesangial cells. European Journal of Cell Biology. 2012;91(10):774–781. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ungvari Z, Bailey-Downs L, Gautam T, et al. Adaptive induction of NF-E2-related factor-2-driven antioxidant genes in endothelial cells in response to hyperglycemia. American Journal of Physiology. 2011;300(4):H1133–H1140. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00402.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pi J, Zhang Q, Fu J, et al. ROS signaling, oxidative stress and Nrf2 in pancreatic beta-cell function. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2010;244(1):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park CH, Noh JS, Kim JH, et al. Evaluation of morroniside, iridoid glycoside from Corni Fructus, on diabetes-induced alterations such as oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in the liver of type 2 diabetic db/db mice. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2011;34(10):1559–1565. doi: 10.1248/bpb.34.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koya D, Hayashi K, Kitada M, Kashiwagi A, Kikkawa R, Haneda M. Effects of antioxidants in diabetes-induced oxidative stress in the glomeruli of diabetic rats. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2003;14(3):S250–S253. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000077412.07578.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sechi LA, Ceriello A, Griffin CA, et al. Renal antioxidant enzyme mRNA levels are increased in rats with experimental diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1997;40(1):23–29. doi: 10.1007/s001250050638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang T, Wang F, Xu HX, et al. Activation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 and PPARγ, plays a role in the genistein-mediated attenuation of oxidative stress-induced endothelial cell injury. British Journal of Nutrition. 2013;109(2):223–235. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512001110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abraham NG, Kappas A. Pharmacological and clinical aspects of heme oxygenase. Pharmacological Reviews. 2008;60(1):79–127. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bao W, Song F, Li X, et al. Plasma heme oxygenase-1 concentration is elevated in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(8, article e12371) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rodriguez F, Lopez B, Perez C, et al. Chronic tempol treatment attenuates the renal hemodynamic effects induced by a heme oxygenase inhibitor in streptozotocin diabetic rats. American Journal of Physiology. 2011;301(5):R1540–R1548. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00847.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Csonka C, Pataki T, Kovacs P, et al. Effects of oxidative stress on the expression of antioxidative defense enzymes in spontaneously hypertensive rat hearts. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2000;29(7):612–619. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00365-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Judge S, Young MJ, Smith A, Hagen T, Leeuwenburgh C. Age-associated increases in oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme activities in cardiac interfibrillar mitochondria: implications for the mitochondrial theory of aging. FASEB Journal. 2005;19(3):419–421. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2622fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miguel F, Augusto AC, Gurgueira SA. Effect of acute vs chronic H2O2-induced oxidative stress on antioxidant enzyme activities. Free Radical Research. 2009;43(4):340–347. doi: 10.1080/10715760902751894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Díaz-Flores M, Angeles-Mejia S, Baiza-Gutman LA, et al. Effect of an aqueous extract of Cucurbita ficifolia Bouchéon the glutathione redox cycle in mice with STZ-induced diabetes. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2012;144(1):101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lau A, Villeneuve NF, Sun Z, Wong PK, Zhang DD. Dual roles of Nrf2 in cancer. Pharmacological Research. 2008;58(5-6):262–270. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schmid H, Boucherot A, Yasuda Y, et al. Modular activation of nuclear factor-κB transcriptional programs in human diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2006;55(11):2993–3003. doi: 10.2337/db06-0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim J, Sohn E, Kim CS, Jo K, Kim JS. The role of high-mobility group box-1 protein in the development of diabetic nephropathy. American Journal of Nephrology. 2011;33(6):524–529. doi: 10.1159/000327992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Palanisamy N, Kannappan S, Anuradha CV. Genistein modulates NF-κB-associated renal inflammation, fibrosis and podocyte abnormalities in fructose-fed rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2011;667(1–3):355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Viatour P, Merville MP, Bours V, Chariot A. Phosphorylation of NF-κB and IκB proteins: implications in cancer and inflammation. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2005;30(1):43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alves M, Calegari VC, Cunha DA, Saad MJA, Velloso LA, Rocha EM. Increased expression of advanced glycation end-products and their receptor, and activation of nuclear factor kappa-B in lacrimal glands of diabetic rats. Diabetologia. 2005;48(12):2675–2681. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Navarro-González JF, Jarque A, Muros M, Mora C, García J. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha as a therapeutic target for diabetic nephropathy. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 2009;20(2):165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Navarro JF, Milena FJ, Mora C, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene expression in diabetic nephropathy: relationship with urinary albumin excretion and effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition. Kidney International. 2005;(99):S98–S102. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Taslipinar A, Yaman H, Yilmaz MI, et al. The relationship between inflammation, endothelial dysfunction and proteinuria in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical & Laboratory Investigation. 2011;71(7):606–612. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2011.598944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu F, Chen HY, Huang XR, et al. C-reactive protein promotes diabetic kidney disease in a mouse model of type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2011;54(10):2713–2723. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2237-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Czyzewska J, Wasilewska K, Kamińska J, Koper O, Kemona H, Jakubowska I. Assess the impact of concentrations of inflammatory markers IL-6, CRP in the presence of albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes. Polski Merkuriusz Lekarski. 2012;32(188):98–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hall WL, Vafeiadou K, Hallund J, et al. Soy-isoflavone-enriched foods and inflammatory biomarkers of cardiovascular disease risk in postmenopausal women: interactions with genotype and equol production. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2005;82(6):1260–1268. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.6.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fanti P, Asmis R, Stephenson TJ, Sawaya BP, Franke AA. Positive effect of dietary soy in ESRD patients with systemic inflammation—correlation between blood levels of the soy isoflavones and the acute-phase reactants. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2006;21(8):2239–2246. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kaur H, Chien A, Jialal I. Hyperglycemia induced toll like receptor 4 expression and activity in mouse mesangial cells: relevance to diabetic nephropathy. American Journal of Physiology. 2012;303(8):F1145–F1150. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00319.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gottstein N, Ewins BA, Eccleston C, et al. Effect of genistein and daidzein on platelet aggregation and monocyte and endothelial function. British Journal of Nutrition. 2003;89(5):607–615. doi: 10.1079/BJN2003820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Surh YJ, Chun KS, Cha HH, et al. Molecular mechanisms underlying chemopreventive activities of anti-inflammatory phytochemicals: down-regulation of COX-2 and iNOS through suppression of NF-κB activation. Mutation Research. 2001;480-481:243–268. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(01)00183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li YS, Wu LP, Li KH, et al. Involvement of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) in the downregulation of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) by genistein in gastric cancer cells. Journal of International Medical Research. 2011;39(6):2141–2150. doi: 10.1177/147323001103900610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Way KJ, Katai N, King GL. Protein kinase C and the development of diabetic vascular complications. Diabetic Medicine. 2001;18(12):945–959. doi: 10.1046/j.0742-3071.2001.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xia P, Aiello LP, Ishii H, et al. Characterization of vascular endothelial growth factor’s effect on the activation of protein kinase C, its isoforms, and endothelial cell growth. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1996;98(9):2018–2026. doi: 10.1172/JCI119006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kelly DJ, Zhang Y, Hepper C, et al. Protein kinase C β inhibition attenuates the progression of experimental diabetic nephropathy in the presence of continued hypertension. Diabetes. 2003;52(2):512–518. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Malhotra A, Kang BPS, Cheung S, Opawumi D, Meggs LG. Angiotensin II promotes glucose-induced activation of cardiac protein kinase C isozymes and phosphorylation of troponin I. Diabetes. 2001;50(8):1918–1926. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.8.1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Palanisamy N, Venkataraman AC. Beneficial effect of genistein on lowering blood pressure and kidney toxicity in fructose-fed hypertensive rats. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512003819. British Journal of Nutrition. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Qi MY, Kai-Chen, Liu HR, Su YH, Yu SQ. Protective effect of Icariin on the early stage of experimental diabetic nephropathy induced by streptozotocin via modulating transforming growth factor β1 and type IV collagen expression in rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2011;138(3):731–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Anjaneyulu M, Berent-Spillson A, Inoue T, Choi J, Cherian K, Russell JW. Transforming growth factor-β induces cellular injury in experimental diabetic neuropathy. Experimental Neurology. 2008;211(2):469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kim YS, Kim NH, Jung DH, et al. Genistein inhibits aldose reductase activity and high glucose-induced TGF-β2 expression in human lens epithelial cells. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2008;594(1–3):18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Behloul N, Wu G. Genistein: a promising therapeutic agent for obesity and diabetes treatment. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2013;698(1–3):31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]