Based on evidence from a literature search and consensus expert opinion, the Mind Exchange program provides practical guidance in the diagnosis, ongoing monitoring, and treatment of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder that is of direct relevance to daily practice.

Keywords: AIDS dementia complex, HIV-associated dementia (HAD), HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND), HIV encephalopathy, neurocognitive impairment

Abstract

Many practical clinical questions regarding the management of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND) remain unanswered. We sought to identify and develop practical answers to key clinical questions in HAND management. Sixty-six specialists from 30 countries provided input into the program, which was overseen by a steering committee. Fourteen questions were rated as being of greatest clinical importance. Answers were drafted by an expert group based on a comprehensive literature review. Sixty-three experts convened to determine consensus and level of evidence for the answers. Consensus was reached on all answers. For instance, good practice suggests that all HIV patients should be screened for HAND early in disease using standardized tools. Follow-up frequency depends on whether HAND is already present or whether clinical data suggest risk for developing HAND. Worsening neurocognitive impairment may trigger consideration of antiretroviral modification when other causes have been excluded. The Mind Exchange program provides practical guidance in the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of HAND.

Despite advances in the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [1], the central nervous system (CNS) is still often affected by this disease. Impairment of cognition caused by HIV disease is known as HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND) [2]. Importantly, compared with unaffected populations, HAND, even in its mild form, is associated with lower medication adherence [3], less ability to perform the most complex daily tasks [4–7], worse quality of life [8], difficulty obtaining employment, and shorter survival [8]. Athough the incidence of the most severe form of HAND—HIV-associated dementia (HAD)—has declined in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) [9], the incidence and prevalence of milder forms (asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment [ANI] and mild neurocognitive disorder [MND]) have remained stable or perhaps even increased [10]. In addition, as cART-treated patients survive into older age, there could be a rise in HAND due to interactive effects of chronic immune activation and aging on the CNS [11].

Gaps remain in translating emerging neuro-HIV research findings into clinical practice [12]. To address this problem, the Mind Exchange program was established with the goal to provide guidance of direct relevance to daily clinical practice. In this communication we describe the process of expert consensus development and specific recommendations on HAND diagnosis and management, based on the best available evidence.

METHODS

Sixty-six specialists from a range of disciplines (including HIV clinicians, neurologists, neuropsychologists, clinical psychologists, and psychiatrists who care for and have experience with HIV patients) from 30 countries provided input into the Mind Exchange program, which took place between February 2011 and January 2012. The program was overseen by a steering committee of 5 experts, including 2 infectious disease specialists (from Italy and the United States), a neurologist (from Germany), a neuropsychiatrist (from the United States), and a clinical psychologist (from Spain).

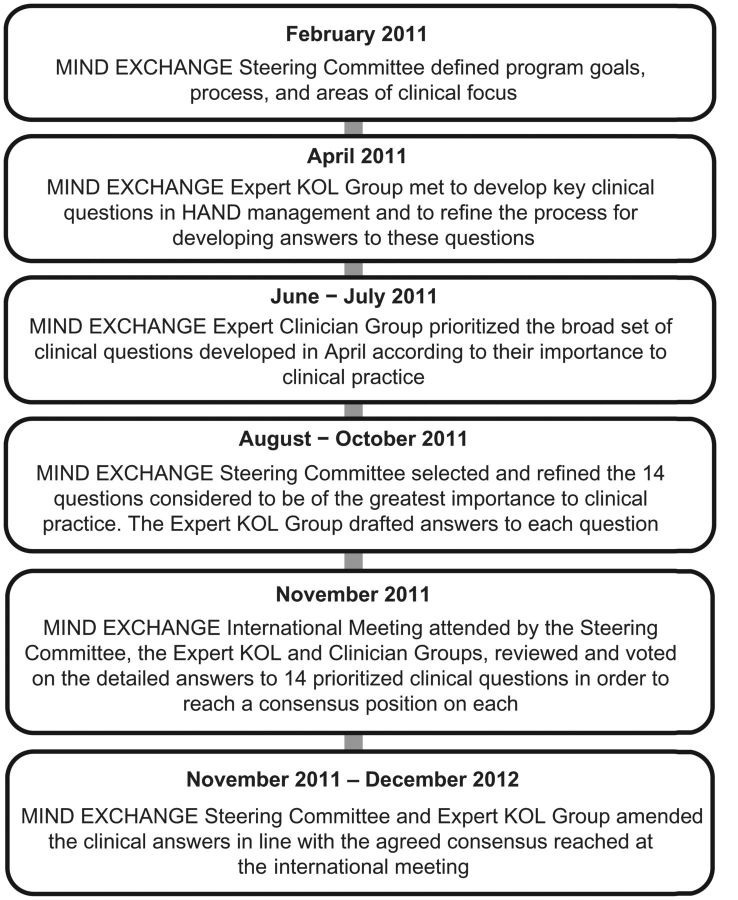

The program comprised several stages (Figure 1). A broad list of clinical questions across the 5 topics (screening, diagnosis, monitoring, treatment/interventions, and prevention of HAND) was generated by a core group of international experts in a face-to-face meeting. A total of 83 questions were identified and included in a questionnaire for prioritization by the core expert group and a wider group of HIV clinicians; the questionnaire was circulated and returned by email, with 65 individuals from 30 countries responding. This process resulted in a final set of 14 questions identified as of critical clinical importance to be addressed during the remainder of the program.

Figure 1.

Overview of the Mind Exchange program. Abbreviation: KOL, key opinion leader.

A comprehensive literature search of PubMed and the Cochrane Library was performed for each of the 14 questions by a research or clinical fellow, or a member of the core expert group, using question-specific search strings and predefined limits (no time limit was specified). Abstracts from key international conferences were also searched.

For each question, a draft practical answer was generated by 2 or 3 members of the core expert group based on the findings of the literature review and their clinical opinion. Answers were reviewed by the steering committee and refined by the expert group. Following this, an international meeting with the steering committee, core expert group, and broader HIV clinician group was held to discuss and further refine the draft answers. These 63 participants from 30 countries voted on their level of agreement with each draft answer using a scale of 1–9 (where 1 = strong disagreement and 9 = strong agreement). Consensus was defined as at least 75% of participants scoring within the 7–9 range. If <75% of participants scored within this range, the answer was debated and revised, followed by a second vote. Similar voting methodology has been employed in development of other consensus-based guidelines in the United Kingdom [13, 14].

The core expert group then further refined the answers to improve clarity and to reduce their length for this document. No substantive changes in the content or meaning of the answers were made. A level of evidence and grade of recommendation was assigned to each statement in the final answers, in accordance with the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) 2009 criteria [15]. This system covers all study types and is appropriate for assigning levels of evidence across the broad range of clinical questions.

RESULTS

The 14 key questions are presented in Table 1. Agreement was achieved on the draft answers to all 14 questions at the international meeting. Here we present a summary of the major points of the guidance derived from each of the answers to the 14 questions.

Table 1.

Fourteen Key Clinical Questions That Were Identified and Addressed During the International Program

| 1 | Which patients should be screened for HAND, and when? How often should patients be screened? |

| 2 | How can physicians identify patients at greater risk of HAND? |

| 3 | Which tools should be used to screen for HAND? |

| 4 | Which comorbidities should be considered in a patient with HAND? |

| 5 | How can HAND be differentiated from neurodegenerative diseases in older patients? |

| 6 | How should neuropsychological testing be approached in the diagnosis of HAND? |

| 7 | In addition to cognitive testing, which other assessments should be used in the diagnosis of HAND (eg, psychiatric assessment, lumbar puncture/CSF analysis, imaging, exclusion of other pathologies)? |

| 8 | What is the role of lumbar puncture/CSF analysis in the management of HAND, and when should it be performed? |

| 9 | When, and how often, should neurocognitive performance be reviewed in patients who have been diagnosed with HAND? |

| 10 | What is the natural history of ANI and MND, and how should this impact patient management? |

| 11 | What interventions should be considered in treated patients with persistent or worsening NCI and CSF viral load <50 copies/mL (nondetectable)? Should the ARV still be changed when the virus is not detectable in the CSF? |

| 12 | What is the risk of ARV-related neurotoxicity? What should be done if ARV neurotoxicity is suspected? |

| 13 | When/how should pharmacological agents other than ARV be used in the management of HAND? |

| 14 | What can be done to prevent HAND? |

Abbreviations: ANI, asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment; ARV, antiretroviral; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; HAND, human immunodeficiency virus–associated neurocognitive disorder; MND, mild neurocognitive disorder; NCI, neurocognitive impairment.

Screening for HAND

It is appropriate to assess neurocognitive functioning in all patients with HIV (CEBM 5; grade of recommendation [GOR] D) as there is limited rationale for screening only symptomatic patients (CEBM 2b) [16–19] or only those with recognized risk factors for HAND (eg, nadir CD4+ T-cell counts <200 cells/μL) (CEBM 2b; GOR C) [20]. Furthermore, because the CNS is commonly one of the first targets of HIV infection, good practice suggests that a patient's neurocognitive profile should be assessed early (within 6 months of diagnosis, as soon as clinically appropriate) using a sensitive screening tool (CEBM 5; GOR D) [21]. If possible, screening should take place before the initiation of cART (CEBM 5; GOR D), as this will establish accurate baseline data and allow for subsequent changes to be more accurately assessed.

Although there are insufficient data to establish the best time for follow-up assessments (CEBM 2b) [22], the consensus group agreed that screening for HAND should occur every 6–12 months in higher-risk patients or every 12–24 months in lower-risk patients (CEBM 5; GOR D). Several risk factors (Table 2) have been independently associated with an increased likelihood of HAND. The clinical significance of risk factors should be considered in light of the patient's full medical history. Screening should also be carried out immediately if there is evidence of clinical deterioration (CEBM 5, GOR D) or at the time of major changes in clinical status (eg, cART initiation or change or diagnosis of mental health disorders; CEBM 3b; GOR C) [23].

Table 2.

Comorbidities and Risk Factors Important to the Identification and Differential Diagnosis of HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorder

| Evidence-supported risk factors | Risk Factor/Comorbidity for HAND and/or Non-HIV-Related NCI | Can Assist Identification of Patients |

CEBM Levels (See Question Details for References) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Current HAND | At Risk of Developing HAND in Future | At Risk of Non-HIV-Related NCI | |||

| Readily assesiable in clinic | |||||

| Disease factors | Low nadir CD4+ T-cell count | X | X | CEBM 1b | |

| High plasma HIV RNA; high CSF HIV RNA | X | X | CEBM 2b | ||

| Low current CD4 (pre-cART) | X | X | CEBM 2b | ||

| Presence of past HIV-related CNS diseases | X | X | CEBM 1b | ||

| Longer HIV duration | X | X | CEBM 2b | ||

| Treatment factors | Low cART adherence | X | X | CEBM 1b | |

| Episodes of cART interruption | X | X | CEBM 2a | ||

| Nonoptimal cART regimen | X | X | CEBM 2a | ||

| Short cART duration (related to treatment failure) | X | X | CEBM 1b | ||

| Comorbidities | Positive HCV serostatus with high HCV RNA | X | X | X | CEBM 1b |

| History of acute CV event | X | CEBM 1b | |||

| CV risk factors (hyperlipidemia, elevated blood pressure, chronic diabetes, and diabetes type II) | X | CEBM 1/2b | |||

| Anemia and thrombocytopenia | X | X | X | CEBM 1/2b | |

| Demographic factors | Older age | X | X | X | CEBM 1b |

| Low level of educational achievement | X | X | X | CEBM 2b | |

| Ethnicity | X | X | X | CEBM 2b | |

| Sex (female, as associated with lower socioeconomic status in some countries) | X | X | X | CEBM 3a | |

| Lack of access to standard care; poverty | X | X | X | CEBM 3b | |

| Other neurological and psychiatric factors | Neuropsychiatric disorders, eg, MDD, anxiety, PTSD, psychosis, bipolar disorder (current or history of) | X | X | X | CEBM 2b |

| Illicit drug/alcohol abuse/dependence (current or history of) | X | X | X | CEBM 2a | |

| Syphilis or systemic infection | X | X | X | CEBM 2b | |

| Alzheimer's disease | X | Use APA (in press) | |||

| Cerebrovascular disease | X | Use APA (in press) | |||

| Traumatic brain injury and seizure | X | X | X | CEBM 2b | |

| Vitamin or hormone deficiency | X | Use APA (in press) | |||

| Prior HCV coinfectiona | X | CEBM 2b | |||

| Complex cART factors | Lower CPE | X | X | CEBM 2a | |

| cART neurotoxicity | X | CEBM 3b | |||

| Difficult to assess in clinic | |||||

| Biomarkers | Abnormal CSF neopterin | X | CEBM 2a | ||

| Abnormal plasma HIV DNA | X | CEBM 2b | |||

| Abnormal NFL | X | CEBM 2a | |||

| Abnormal MCP–1 | X | CEBM 2a | |||

| Abnormal serum osteopontin | X | CEBM 4 | |||

Abbreviations: APA, American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (in press; see www.dsm5.org); ARV, antiretroviral; cART, combined antiretroviral therapy; CEBM, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine; CNS, central nervous system; CPE, central nervous system penetration efficiency; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CV, cardiovascular; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; HAND, HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MDD, major depressive disorder; NCI, neurocognitive impairment; pts, patients; NFL, neurofilament light chain protein; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; RNA, ribonucleic acid.

a Evidence of previous HCV infection (ie, in HCV-infected patients with no active HCV RNA, and without liver cirrhosis or failure) should also be considered a risk factor for non-HIV-related NCI [2]. For full referencing of this table please see the Supplementary Data.

Many brief screening approaches have been proposed for the detection of neurocognitive disorders; the benefits and limitations of those tools for which there is substantial literature on their use in HAND are presented in Table 3. In addition to paper-based tools, some computerized tools are also available for screening (eg, CogState [34]; CANTAB reaction time [35]). No single tool is suitable for use across all practice settings, and the choice of a HAND screening tool depends on a number of considerations, including the availability of a clinician suitably trained to administer and interpret each tool; whether the clinician wants to screen for HAD only or for the milder forms of HAND; the financial and time cost of testing; and the characteristics of the population in which the tool will be used (CEBM 5; GOR D). Neurocognitive screening tools should not be used in isolation from clinical information (eg, from brief questioning [see full answer to question 3 in the Supplementary Data] [24]) and risk profiles, which can be used to increase suspicion for HAND. Screening tests typically underestimate the true prevalence of HAND because they lack sensitivity to milder forms of the condition.

Table 3.

Useful Available Tools for Screening for HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorder

| Tool | Description | Benefits | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| HDS [24–28] | A validated brief screening tool designed primarily for use in outpatient clinics to identify dementia in people with HIV using NP tests of motor speed, concentration, and memory. |

|

|

| IHDS [27, 29, 30] | A sensitive and rapid screening test for HIV dementia, which relies on assessment of motor speed and psychomotor speed It includes 3 subtests: timed finger- tapping; timed alternating hand sequence test; recall of 4 items at 2 min |

|

|

| Total Recall measure of the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised [31] | Originally developed to detect dementia, it has been shown to measure neurocognitive impairment in HIV. In particular, it can be used to detect verbal learning and retrieval deficits |

|

|

| Grooved Pegboard Test [31] | Test of manipulative dexterity requiring complex visual-motor coordination |

|

|

| Executive Interview [32] | Developed and validated in geriatric patients and patients with Alzheimer's disease as a brief assessment of frontal or executive neurocognitive function Has been shown to be a significant individual predictor of dementia in hospitalized patients with HIV |

|

|

| Cognitive functional status subscale of the (MOS-HIV) [33] | MOS-HIV is a widely used instrument to assess QoL in patients with HIV. Its neurocognitive functional status subscale measures functional status owing to neurocognitive impairment. Best use may be as a screening instrument to select those subjects whose self-reported neurocognitive functional status warrants formal NP test evaluation |

|

|

Abbreviations: HAD, HIV-associated dementia; HAND, HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder; HDS, HIV Dementia Scale; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IHDS, International HIV Dementia Scale; MOS-HIV, Medical Outcomes Study HIV Health Survey; NP, neuropsychological; QoL, quality of life.

Neurocognitive/Neuropsychological Assessment (as Part of HAND Diagnostic Procedure)

A comprehensive neuropsychological (NP) evaluation is the accepted standard for the evaluation of HAND according to published criteria [2]. Because NP resources are limited in many clinical settings, a presumptive clinical diagnosis of HAND could be based on symptom questionnaires, screening tools, functional assessments, and limited NP testing. Patients with particular characteristics could then be targeted for full NP assessments: patients demonstrating neurocognitive impairment (NCI) at neurocognitive screening, if the differential diagnosis of HAND is in doubt (CEBM 5; GOR D) [2]; when the HAND diagnosis is uncertain (CEBM 5; GOR D) [2]; in patients who have evidence of impaired everyday functioning (CEBM 5; GOR D) [2]; in patients with evidence of clinical progression of HAND or increasing neurocognitive complaints (not associated with depression; CEBM 5; GOR D) [2]; and in patients identified as at risk of HAND based on traditional risk factors for HAD (eg, nadir CD4+ T-cell count below approximately 200 cells/μL), particularly if neurocognitive difficulties are also evident (CEBM 1b; GOR B) [36].

Comprehensive NP testing should include a test battery of at least 5 neurocognitive domains (including verbal/language, attention/working memory, abstraction/executive function, learning/recall, speed of information processing, and motor skills [CEBM 5; GOR D]) [2] using standard and validated instruments for detection of HAND administered and interpreted by appropriately trained professionals [37]. Furthermore, tests should be performed at times when the patient is not experiencing excessive fatigue or severely depressed mood, and when the general medical status is stable (ie, without other active systemic diseases). The NP tests selected for use should ideally have been validated in the language and culture of the patient. The use of appropriate normative data from a healthy community population is recommended for the correct interpretation of standard NP tests with quantitative outcomes [37–39]. Furthermore, in follow-up testing, the use of normative longitudinal data is recommended to adjust for the impact of repeated testing (the “learning or practice effect”) on test sensitivity (CEBM 1c; GOR B) [40, 41].

Differential Diagnosis of HAND

Various conditions (comorbidities) may either suggest a non-HIV cause for NCI, or their presence may compound HIV's effect on the CNS. To identify comorbidities and make a judgment as to whether or not they contribute to NCI, a number of assessments (in addition to neurocognitive assessments already described) should be used in HIV-infected individuals with suspected or demonstrated NCI (Table 4). In addition, in older patients, it is important to differentiate HAND from neurodegenerative disorders. Here both pattern and course of progression of NP impairment, and in certain instances, ancillary diagnostic information such as brain imaging, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies, and blood tests can be helpful (Table 4). For example, in the older person with well-controlled HIV, the differential diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease may be suggested by progressive cognitive impairment with prominent difficulties in learning new information, rapid forgetting, and language problems (eg, deficits in naming and comprehension, which are not prominent in HAND), in the context of apolipoprotein e4 polymorphism (CEBM 2b; GOR B) [56–59].

Table 4.

Tests Additional to Neuropsychological Assessment That Should Be Used in the Diagnosis of HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorder in HIV-Infected Patients With Suspected or Demonstrated Neurocognitive Impairment

| Test | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Thorough medical and neurological history | Will identify previous conditions associated with an acquired static encephalopathy (such as TBI, OIs) |

| Developmental history (academic performance, occupational attainment) | Will help to establish the premorbid level of neurocognitive functioning (CEBM 3b; GOR C) [42] |

| Assessment of past and active alcohol and substance abuse or dependence using DSM-IV | Acute intoxication or withdrawal or active substance abuse or dependence can interfere with reliable evaluation of neurocognitive status (CEBM 3a; GOR B) [43–45]. Poor performance on NP testing may be explained, at least in part, by extensive past history of alcohol or substances |

| Assessment of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder using a structured questionnaire (CEBM 5; GOR D) | To identify psychiatric conditions that may influence self-reported neurocognitive performance as well as performance on some neurocognitive tests |

| Neurological examination | To assess neurological signs (eg, asterixis, myoclonus, ocular motor signs, spasticity) that may suggest an etiology other than HIV infection (CEBM 5; GOR D) |

| Laboratory studies | To stage HIV infection (CD4 cell count and HIV RNA) and assess for comorbid infections (eg, neurosyphilis, hepatitis C) and metabolic and endocrine disorders (hypothyroidism and hypogonadism) (CEBM 5; GOR D) |

| CSF analysis | For OIs and other infections (CEBM 1; GOR A) [46–49] and in individuals with high CD4 T-cell count and undetectable plasma HIV RNA (to assess for detectable CSF HIV RNA) [50]; genotypic resistance testing in patients with detectable HIV RNA |

| MRI | To evaluate other conditions that may impact on neurocognitive impairment (eg, active opportunistic CNS disease, cerebral infarction or hemorrhage, subcortical [vascular] leukoencephalopathy, and inactive cerebral lesions related to prior CNS opportunistic disease; CEBM 2b; GOR C) [51, 52]. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy appears more sensitive than structural MRI in milder forms of HAND and shows different metabolite changes in HAND subtypes [53, 54] |

| Lawton & Brody's modified Activities of Daily Living scale and the Patient's Assessment of Own Functioning Inventory | Provides a formal assessment of functional impairment [22, 54, 55] |

Abbreviations: CEBM, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine; CNS, central nervous system; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; GOR, grade of recommendation; HAND, HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NP, neuropsychological; OI, opportunistic infection; RNA, ribonucleic acid; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

CSF analysis should be performed in patients with neurological symptoms or signs (CEBM 2a; GOR B), preferably at presentation (CEBM 2a; GOR C) [46, 47], and should be preceded by imaging (to avoid lumbar puncture–associated risk). In these patients, CSF analysis should be performed to exclude non-HIV neurological conditions (eg, CNS-opportunistic infections and other infections; CEBM 2b; GOR C) [46–49, 60].

Monitoring HAND

In the absence of data from large-scale outcome studies of HAND (CEBM 5; GOR D), experts recommend that the frequency of neurocognitive monitoring should be increased in patients who (1) demonstrate clinical worsening of HIV disease; (2) have a history of low nadir CD4 (eg, <200 cells/μL), which is associated with worse neurocognitive outcomes; (3) are not receiving ART; (4) do not achieve virologic suppression despite cART; and (5) develop new or worsened neurologic symptoms or signs (CEBM 5; GOR D). Clinically stable patients can be reviewed less often (approximately every 2 years). Patients may detect neurocognitive difficulties before they are noted by clinicians. Consequently, those reporting neurocognitive difficulties should be evaluated fully (CEBM 1b; GOR B) [24]. However, self-report alone can either underestimate (as a result of impaired patient insight) or overestimate (as a result of comorbid anxiety and depression) true neurocognitive difficulties (CEBM 1b) [61]. Therefore, the consideration of both the clinical history and the personal complaints is needed to best determine time to follow-up.

Recommendations for monitoring patients are presented in Table 5. For patients commencing cART, the earliest time point at which improvement is expected is 1 month, with several studies showing improvement by 2 months [67, 68], and some by as much as 9 months (CEBM 1b) [64, 69]. Earlier responses may be seen in patients who are naive to cART (CEBM 1a and 1b) [68, 70, 71].

Table 5.

Recommendations for Monitoring Patients With HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorder

| Patient Type | Monitoring Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Patients with HAND not on cART | |

| Patients with HAD or MND commencing cART |

|

| Patients with ANI commencing therapy |

Abbreviations: ANI, asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment; cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; CEBM, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine; GOR, grade of recommendation; HAD, HIV-associated dementia; HAND, HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MND, mild neurocognitive disorder.

Most patients who attain virologic suppression in blood will also do so in CSF. Thus, there is no general indication to repeat CSF analysis following cART initiation (CEBM 2b; GOR B) [60]. CSF analysis may be repeated after at least 12 weeks in patients with undetectable plasma HIV RNA who do not improve neurologically (CEBM 5; GOR D), and in those who changed cART because of CSF viral escape (CEBM 4; GOR C) [72].

Treatment and Prevention

There are no systematic published studies on the progression of ANI to MND, or of MND to HAD. There is some evidence that markers of progression of HIV disease (low CD4+ T-cell count, AIDS diagnosis, high plasma HIV RNA), NP status (worse processing speed), and major depressive disorder may be associated with worsening of NP performance over time. It is not possible from existing data to conclude whether patients with successful treatment (ie, plasma HIV RNA <50 copies/mL) are at risk of progression and there are no systematic studies addressing the extent to which neurocognitive deficit may be permanent or reversible.

Data show that cART for approximately 1 year is associated with modest benefits in NP functioning, particularly attention, processing speed, and executive performance (CEBM 1a) [73–77]. The degree of improvement correlates with changes in CD4+ T-cell counts (CEBM 1a) [42, 78–82]. Treatment with antiretrovirals that have greater distribution into the CNS (CNS penetration) has been associated with better neurocognitive outcomes in some trials (CEBM 2b; GOR B); however, results are not consistent and randomized trials with large sample sizes are needed to corroborate these findings (Table 6) [64, 74, 76, 85]. Thus, the benefits of changing cART to improve CNS penetration for individuals whose infection is already well controlled are unproven.

Table 6.

Central Nervous System Penetration-Effectiveness Ranking 2010

| CNS Penetration-Effectiveness Ranking | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRTIs | Zidovudine | Abacavir | Didanosine | Tenofovir |

| Emtricitabine | Lamivudine | |||

| Stavudine | ||||

| NNRTIs | Nevirapine | Delavirdine | Etravirine | |

| Efavirenz | ||||

| PIs | Indinavir/r | Darunavir/r | Atazanavir | Nelfinavir |

| Fosamprenavir/r | Atazanavir/r | Ritonavir | ||

| Indinavir | Fosamprenavir | Saquinavir | ||

| Lopinavir/r | Saquinavir/r | |||

| Tipranavir/r | ||||

| Entry/fusion inhibitors | Maraviroc | Enfuvirtide | ||

| Integrase inhibitors | Raltegravir |

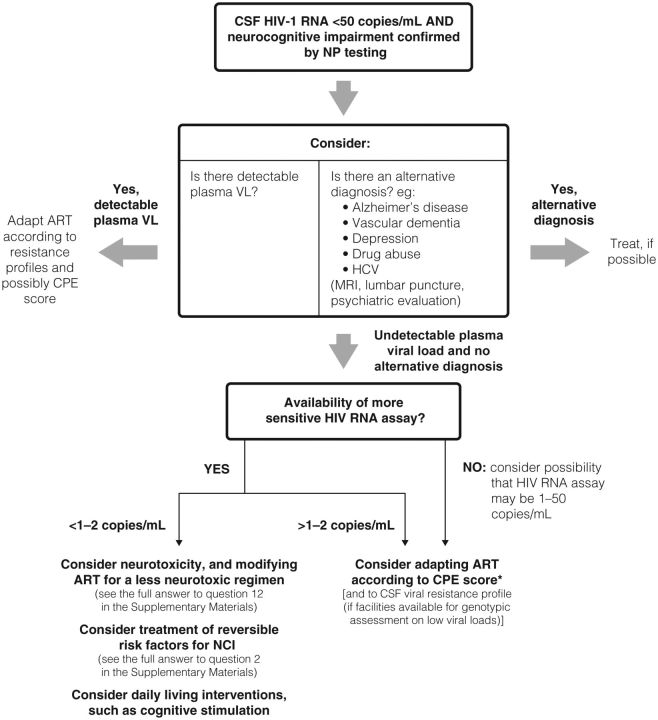

In patients with persistent or worsening NCI and CSF HIV RNA <50 copies/mL, other possible causes of NCI must be considered (CEMB 5; GOR D). After ruling out alternative diagnoses, HAND should be considered. If HIV RNA is detectable in the plasma, we suggest first obtaining confirmation that the patient is adherent to their cART, as neurocognitive difficulties can interfere with adherence and, second, adapting the regimen according to resistance profiles and possibly the CNS penetration-effectiveness (CPE) score if appropriate (CEBM 2b; GOR C) [86]. If HIV RNA is undetectable in the plasma and CSF, we recommend that a more sensitive HIV RNA assay with a lower limit of detection of 1–2.5 copies/mL be performed on the CSF (currently available only in research settings). If HIV RNA is detectable using a more sensitive assay, modification of the cART regimen according to CPE score (when appropriate) and to CSF viral resistance profile (if possible) may be an option. If the more sensitive HIV RNA assay is not available, the clinician may suspect the possibility of low-level CSF HIV RNA >2.5 copies/mL and consider regimen modification (CEBM 2b; GOR C) (Figure 2) [87, 88].

Figure 2.

Algorithm showing management of treated patients with persistent or worsening neurocognitive impairment and undetectable cerebrospinal fluid human immunodeficiency virus RNA (<50 copies/mL). Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; CPE, central nervous system penetration effectiveness; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NCI, neurocognitive impairment; NP, neuropsychological; RNA, ribonucleic acid; VL, viral load.

If treated patients have persistent NCI despite effective cART, the possibility of cART neurotoxicity must be considered. Evidence in the literature for antiretroviral neurotoxicity causing persistent NCI during stable cART is limited because it has not been systematically studied. Although some findings suggest neurocognitive improvement following cessation of cART (CEBM 3b) [89, 90], other reports question that evidence [91]. The use of treatment interruption is not recommended since its benefits do not outweigh its risks (CEBM 1b; GOR B) [92–94]. Evidence for the development of neuropsychiatric symptoms (eg, sleep disturbance, dizziness, anxiety, depression) is greatest for efavirenz; however, these effects typically occur early in therapy and in many cases resolve spontaneously [95, 96]. If cART neurotoxicity is suspected, and CNS side effects persist for >4 weeks, consider therapeutic drug monitoring followed by dose adjustment if indicated (CEBM 2b; GOR C) [97, 98]. If symptoms continue to persist, consider switching to an alternative treatment (CEBM 5; GOR D) [99].

In addition to cART, several drugs (including minocycline, memantine, selegiline, lithium, valproic acid, lexipafant, CPI 1189, peptide T, nimodipine, and psychostimulants) have been evaluated as potential therapies for HAND. Although there is evidence of good safety and tolerability in most studies, effectiveness has not been established (CEBM 1a) [100]. No therapy other than cART is currently recommended for routine treatment of HAND in the clinic.

Direct and indirect data tend to show benefits in treating potential comorbidities, such as hepatitis C virus, cardiovascular risk factors, metabolic disorders, major depressive disorder, and anxiety disorders, to reduce the severity of NCI in HIV-infected patients (CEBM 2b; and 5; GOR C) [101, 102].

There is a limited evidence base for the earlier introduction of cART for the prevention of HAND (CEBM 2b; GOR B) [103]. In general, current treatment guidelines should be followed (CEBM 2b; GOR C) [103]. Earlier treatment of patients at high risk of NCI, for instance, older people, could be considered (CEBM 5; GOR D). There are no data on the use of CNS-penetrating cART for preventing (as opposed to treating) HAND; therefore, there is no evidence to support the initiation of therapy with better CNS-penetrating regimens in neurologically normal patients, or in those at greater risk of HAND (CEBM 5; GOR D).

DISCUSSION

We have summarized the key points of the Mind Exchange program, a consensus-based, evidence-driven process to develop and consolidate practical guidance for the screening, diagnosis, monitoring, treatment, and prevention of HAND. The Mind Exchange program included an academically rigorous process, supported by a large number of leading HIV physicians, representing a broad range of clinical opinion from diverse geographic regions and a variety of clinical practices, with the intent to provide insightful, up-to-date, and evidence-based guidance to the HIV medical community. The program was designed to complement rather than duplicate existing guidance in HIV treatment guidelines.

This program does have several limitations. First, although literature searches were based on carefully constructed, formalized keyword strings, the review of the literature does not meet strict criteria for a systematic review. Nonetheless, the searches were thorough, well documented, and carried out in 2 databases and relevant HIV congresses, thus providing a broad database with which to address each of the 14 questions. Second, to provide the most clinically useful guidance within a manageable timeframe, the program did not set out to address all aspects of HAND management, but rather addressed the questions prioritized as most important to clinical practice. Despite this restriction, the answers provided do give a good spread of guidance across the range of HAND management. Finally, the guidance does not take into account differing resource settings, and it may not be possible for all physicians to apply all aspects of the guidance within their practice.

The consensus process has also highlighted areas of HAND diagnosis and management where further research and guidance is needed. For example, although good practice suggests that all patients with HIV should be screened for HAND as early as possible in their disease using a sensitive screening tool, some of the most widely available screening tools have limitations, particularly in their ability to detect milder forms of NCI. Other testing requires involvement of a specialist, especially for scoring and interpretation. In brief, there is no standard and validated, easy-to-perform test to screen for minor neurocognitive disorders applicable in all HIV-infected patients. The HIV Dementia Scale with a modified cutoff of 14 points (as opposed to the classical cutoff of 10 points) is useful in identifying those persons with HAD, but this scale and others are still limited in their ability to detect (and differentiate from other diagnoses) ANI and MND.

There are no data on the role of preventive measures for HAND and there are only emerging data on the progression of milder forms of impairment and the clinical significance of asymptomatic impairment. There are no data regarding the appropriate short monitoring tools for reviewing neurocognitive performance in patients who have been diagnosed with HAND; while access to full NP assessment is appropriate in some patient groups, it remains an option that is not widely affordable. Short and validated monitoring tools for HAND are urgently needed. Last, data from large randomized trials are needed to confirm the potential association of the CNS penetration of cART with improved neurocognitive performance, while issues of potential long-term neurotoxicity demand investigation.

The clinical importance of HAND is receiving increasing attention as patients are surviving longer and neurocognitive health has become an issue of importance in the HIV and general community. Both HIV and non-HIV forms of NCI are diagnosed much earlier than they were in the past [104]. Despite this, some have questioned the benefit of early diagnoses when there is no proven treatment. But in the context of HIV infection, which is likely to be a chronic disease lasting decades in most patients, we have highlighted that there are already better treatment practices and that early diagnosis is a crucial step in identifying patients at risk, as well as patients in need of more frequent monitoring or specific interventions, including medication adherence checks.

Our program has attempted to address the fact that among many HIV clinicians, the knowledge of practical procedures to deal with HAND is limited. This highlights the need for further education and training on the importance of HAND and its clinical implications, particularly around raising awareness of the link between HAND and cART nonadherence, improving understanding of ANI, increasing the understanding and implementation of the neurocognitive diagnosis of HAND, and initiating effective management of HAND once it has been identified.

In conclusion, the Mind Exchange program complements existing guidelines, providing practical guidance in the diagnosis, ongoing monitoring, and treatment of HAND, which is of direct relevance to daily practice.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online (http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. Writing assistance was provided by Sue Cheer, Lucid, United Kingdom, who received funding assistance from Abbott. Abbott was not involved in development or review of this manuscript. The authors maintained complete control over the content of this paper. We also thank the following research and clinical fellows who helped perform the literature searches: Chad Bousman, David Croteau, Alicia Gonzalez, Allyson Ion, Thomas Marcotte, Ignacio Perez-Valero, Dr Tiroboschi, Xavier de la Tribonniére, and Joyce M. Velez.

Mind Exchange Working Group. Steering Committee: Andrea Antinori (National Institute for Infectious Diseases, Rome, Italy), Gabriele Arendt (Department of Neurology, Universitätsklinikum Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany), Igor Grant (HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program and the Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego), Scott Letendre, Chair (HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program and the Division of Infectious Diseases, University of California, San Diego), and Jose A. Muñoz-Moreno (Lluita contra la SIDA Foundation, Germans Trias i Pujol University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain). Core Expert Group: Christian Eggers*, Bruce Brew*, Marie-Josée Brouillette*, Francisco Bernal-Cano*, Adriana Carvalhal*, Paulo Pereira Christo*, Paola Cinque*, Lucette Cysique*, Ronald Ellis*, Ian Everall, Jacques Gasnault*, Ingo Husstedt*, Volkan Korten*, Ladislav Machala, Mark Obermann, Silvia Ouakinin, Daniel Podzamczer, Peter Portegies, Simon Rackstraw, Sean Rourke*, Lorraine Sherr, Adrian Streinu-Cercel, Alan Winston*, Valerie Wojna*, and Yazdan Yazdanpannah* (asterisks indicate the authors who were responsible for reviewing the manuscript). Wider Clinician Group: Gordon Arbess, Jean-Guy Baril, Josip Begovac, Colm Bergin, Paolo Bonfanti, Stefano Bonora, Kees Brinkman, Ana Canestri, Graźyna Cholewińska-Szymańska, Michal Chowers, John Cooney, Marcelo Corti, Colin Doherty, Daniel Elbirt, Stefan Esser, Eric Florence, Gilles Force, John Gill, Jean-Christophe Goffard, Thomas Harrer, Patrick Li, Linos Van de Kerckhove, Gaby Knecht, Shuzo Matsushita, Raimonda Matulionyte, Sam McConkey, Antoine Mouglignier, Shinichi Oka, Augusto Penalva, Klaris Riesenberg, Helen Sambatakou, Valerio Tozzi, Matteo Vassallo, Peter Wetterberg, Alicia Wiercińska Drapato.

Author contributions. S. L., J. M.-M., G. A., and I. G. contributed significantly to the writing and reviewing of this manuscript. In addition, the manuscript was extensively reviewed by B. B., L. C., V. W., J. G., A. W., C. E., F. B.-C., M.-J. B., P. C., R. E., V. K., S. R., I. H., P. P. C., Y. Y., and A. C.

Financial support. Abbott Laboratories provided funding for this 18–month academically rigorous program, but had no involvement in the development, review, or shaping of the recommended guidance. The Steering Committee has been assisted by Lucid, a specialist UK-based medical communication company that was funded by Abbott Laboratories, in the organization of program events and the editorial process for the final program report. Lucid similarly played no part in affecting the nature of the guidance.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Powderly WG. Sorting through confusing messages: the art of HAART. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31(suppl 1):S24–5. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200209011-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, et al. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69:1789–99. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albert SM, Weber C, Todak G. An observed performance test of medication management ability in HIV: relation to neuropsychological status and adherence outcomes. AIDS Behav. 1999;3:121–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger JR, Brew B. An international screening tool for HIV dementia. AIDS. 2005;19:2165–6. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000194798.66670.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farinpour R, Miller EN, Satz P, et al. Psychosocial risk factors of HIV morbidity and mortality: findings from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2003;25:654–70. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.5.654.14577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garvey LJ, Yerrakalva D, Winston A. Do cerebral function test results correlate when measured by a computerized battery test and a memory questionnaire in HIV-1 infected subjects? J Int AIDS Soc. 2008;11(suppl 1):P301. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garvey LJ, Yerrakalva D, Winston A. Correlations between computerized battery testing and a memory questionnaire for identification of neurocognitive impairment in HIV type 1–infected subjects on stable antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2009;25:765–9. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tozzi V, Balestra P, Bellagamba R, et al. Persistence of neuropsychologic deficits despite long-term highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV-related neurocognitive impairment: prevalence and risk factors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:174–82. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318042e1ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sacktor N, Lyles RH, Skolasky R, et al. HIV-associated neurologic disease incidence changes: multicenter AIDS cohort study, 1990–1998. Neurology. 2001;56:257–60. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McArthur JC. HIV dementia: an evolving disease. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;157:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cysique LA, Bain MP, Brew BJ, Marray JM. The burden of HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment in Australia and its estimates for the future. Sex Health. 2011;8:541–50. doi: 10.1071/SH11003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European AIDS Clinical Society. Guidelines on neurocognitive impairment: diagnosis and management, Version 6. :48–9. October 2011 Available at http://www.europeanaidsclinicalsociety.org/images/stories/EACS-Pdf/EACSguidelines-v6.0-English.pdf. Accessed 25 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Donor breast milk banks: the operation of donor breast milk bank services. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG93. Accessed 6 August 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Feverish illness in children: assessment and initial management in children younger than 5 years. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG47. Accessed 6 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Homepage. Available at http://www.cebm.net. Accessed 2 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rourke SB, Halman MH, Bassel C. Neurocognitive complaints in HIV-infection and their relationship to depressive symptoms and neuropsychological functioning. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1999;21:737–56. doi: 10.1076/jcen.21.6.737.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gandhi NS, Skolasky RL, Peters KB, et al. A comparison of performance-based measures of function in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. J Neurovirol. 2011;17:159–65. doi: 10.1007/s13365-011-0023-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tozzi V, Balestra P, Galgani S, et al. Neurocognitive performance and quality of life in patients with HIV infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2003;19:643–52. doi: 10.1089/088922203322280856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woods SP, Moore DJ, Weber E, Grant I. Cognitive neuropsychology of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neuropsychol Rev. 2009;19:152–68. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9102-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cysique LA, Maruff P, Brew BJ. Prevalence and pattern of neuropsychological impairment in human immunodeficiency virus-infected/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) patients across pre- and post-highly active antiretroviral therapy eras: a combined study of two cohorts. J Neurovirol. 2004;10:350–7. doi: 10.1080/13550280490521078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valcour VG, Paul R, Chiao S, Wendelken LA, Miller B. Screening for cognitive impairment in human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:836–42. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heaton RK, Marcotte TD, Mindt MR, et al. The impact of HIV-associated neuropsychological impairment on everyday functioning. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10:317–31. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704102130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathew MM, Bhat JS. Profile of communication disorders in HIV-infected individuals: a preliminary study. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2008;7:223–7. doi: 10.1177/1545109708320682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simioni S, Cavassini M, Annoni JM, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in HIV patients despite long-standing suppression of viremia. AIDS. 2010;24:1243–50. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283354a7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Power C, Selnes OA, Grim JA, McArthur JC. HIV Dementia Scale: a rapid screening test. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;8:273–8. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199503010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bottiggi KA, Chang JJ, Schmitt FA, et al. The HIV Dementia Scale: predictive power in mild dementia and HAART. J Neurolog Sci. 2007;260:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skinner S, Adewale AJ, Deblock L, Gill MJ, Power C. Neurocognitive screening tools in HIV/AIDS: comparative performance among patients exposed to antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2009;10:246–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morgan EE, Woods SP, Scott JC, et al. the HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center (HNRC) Group. Predictive validity of demographically adjusted normative standards for the HIV Dementia Scale. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2008;30:83–90. doi: 10.1080/13803390701233865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sacktor NC, Wong M, Nakasujja N, et al. The International HIV Dementia Scale: a new rapid screening test for HIV dementia. AIDS. 2005;19:1367–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Njamnshi AK, Djientcheu VDP, Fonsah JY, et al. The International HIV Dementia Scale is a useful screening tool for HIV-associated dementia/cognitive impairment in HIV-infected adults in Yaounde, Cameroon. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49:393–7. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e318183a9df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carey CL, Woods SP, Rippeth JD, et al. Initial validation of a screening battery for the detection of HIV-associated cognitive impairment. Clin Neuropsychol. 2004;18:234–48. doi: 10.1080/13854040490501448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berghuis JP, Uldall KK, Lalonde B. Validity of two scales in identifying HIV-associated dementia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1999;21:134–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knippels HM, Goodkin K, Weiss JJ, Wilkie FL, Antoni MH. The importance of cognitive self-report in early HIV-1 infection: validation of a cognitive functional status subscale. AIDS. 2002;16:259–67. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200201250-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cysique LA, Maruff P, Darby D, Brew BJ. The assessment of cognitive function in advanced HIV-1 infection and AIDS dementia complex using a new computerised cognitive test battery. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2006;21:185–94. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gibbie T, Mijch A, Ellen S, et al. Depression and neurocognitive performance in individuals with HIV/AIDS: 2-year follow-up. HIV Med. 2006;7:112–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2006.00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cysique LA, Murray JM, Dunbar M, et al. A screening algorithm for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. HIV Med. 2010;11:642–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Loring DW. Neuropsychological assessment. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heaton RK, Miller SW, Taylor MJ, Grant I. Revised comprehensive norms for an expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: demographically adjusted neuropsychological norms for African American and Caucasian Adults Scoring Program. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O. A compendium of neuropsychological tests: administration, norms, and commentary. 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heaton R, Temkin N, Dikmen S, et al. Detecting change: a comparison of three neuropsychological methods, using normal and clinical samples. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2001;16:75–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salthouse TA, Tucker-Drob EM. Implications of short-term retest effects for the interpretation of longitudinal change. Neuropsychology. 2008;22:800–11. doi: 10.1037/a0013091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Jr, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER study. Neurology. 2010;75:2087–96. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Durvasula RS, Myers HF, Mason K, Hinkin C. Relationship between alcohol use/abuse, HIV infection and neuropsychological performance in African American men. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2006;28:383–404. doi: 10.1080/13803390590935408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Norman LR, Basso M, Kumar A, Malow R. Neuropsychological consequences of HIV and substance abuse: a literature review and implications for treatment and future research. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2009;2:143–56. doi: 10.2174/1874473710902020143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goodwin GM, Pretsell DO, Chiswick A, Egan V, Brettle RP. The Edinburgh cohort of HIV-positive injecting drug users at 10 years after infection: a case-control study of the evolution of dementia. AIDS. 1996;10:431–40. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199604000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Portegies P, Solod L, Cinque P, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of neurological complications of HIV infection. Eur J Neurol. 2004;11:297–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2004.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaplan JE, Benson C, Holmes KH, et al. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Recomm. 2009;58:1–207. MMWR quiz CE1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ances BM, Clifford DB. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders and the impact of combination antiretroviral therapies. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2008;8:455–61. doi: 10.1007/s11910-008-0073-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schouten J, Cinque P, Gisslen M, Reiss P, Portegies P. HIV-1 infection and cognitive impairment in the cART era: a review. AIDS. 2011;13:561–75. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283437f9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robinson-Papp J, Elliott KJ, Simpson DM. HIV-related neurocognitive impairment in the HAART era. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2009;6:146–52. doi: 10.1007/s11904-009-0020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paul RH, Ernst T, Brickman AM, et al. Relative sensitivity of magnetic resonance spectroscopy and quantitative magnetic resonance imaging to cognitive function among nondemented individuals infected with HIV. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2008;14:725–33. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708080910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Becker JT, Maruca V, Kingsley LA, et al. for the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Factors affecting brain structure in men with HIV disease in the post-HAART era. Neuroradiology. 2012;54:113–21. doi: 10.1007/s00234-011-0854-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang L, Lee PL, Yiannoutsos CT, et al. A multicenter in vivo proton-MRS study of HIV-associated dementia and its relationship to age. Neuroimage. 2004;23:1336–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chelune G, Heaton R, Lehman R. Neuropsychological and personality correlates of patients’ complaints of disability. In: Tarter R, Goldstein G, editors. Advances in clinical neuropsychology. New York: Plenum Press; 1986. pp. 95–126. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Valcour V, Watters MR, Williams AE, et al. Aging exacerbates extrapyramidal motor signs in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Neurovirol. 2008;14:362–7. doi: 10.1080/13550280802216494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Woods SP, Dawson MS, Weber E, et al. Timing is everything: antiretroviral nonadherence is associated with impairment in time-based prospective memory. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2009;15:42–52. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708090012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tucker KA, Robertson KR, Lin W, et al. Neuroimaging in human immunodeficiency. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;157:153–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen Y, An H, Zhu H, et al. White matter abnormalities revealed by diffusion tensor imaging in non-demented and demented HIV+ patients. Neuroimage. 2009;47:1154–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mellgren A, Antinori A, Cinque P, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid HIV-1 infection usually responds well to antiretroviral treatment. Antivir Ther. 2005;10:701–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thames AD, Kim MS, Becker BW, et al. Medication and finance management among HIV infected adults: the impact of age and cognition. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2011;33:200–9. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2010.499357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pan Y, Dore G, van der Bij A, Kaldor J, Brew B. Prognosis of AIDS dementia complex (ADC) and predictors of post-ADC survival. Australasian Society of HIV Medicine 12th Annual Conference, Melbourne, Australia, October 2000 Abstract 61. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bouwman FH, Skolasky RL, Hes D, et al. Variable progression of HIV-associated dementia. Neurology. 1998;50:1814–20. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.6.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cysique LA, Vaida F, Letendre S, et al. Dynamics of cognitive change in impaired HIV-positive patients initiating antiretroviral therapy. Neurology. 2009;73:342–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ab2b3b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Navia B, Harezlak J, Schifitto G, et al. A longitudinal study of neurological injury in HIV-infected subjects on stable ART: the HIV Neuroimaging Consortium Cohort Study. 18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Boston, MA, 27 February–2 March 2011. Abstract 56. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cysique LA, Maruff P, Brew BJ. Variable benefit in neuropsychological function in HIV-infected HAART-treated patients. Neurology. 2006;66:1447–50. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000210477.63851.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brew BJ, Halman M, Catalan J, et al. Factors in AIDS dementia complex trial design: results and lessons from the abacavir trial. PLoS Clin Trials. 2007;2:e13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pctr.0020013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tozzi V, Narciso P, Galgani S, et al. Effects of zidovudine in 30 patients with mild to end-stage AIDS dementia complex. AIDS. 1993;7:683–92. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199305000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tozzi V, Balestra P, Galgani S, et al. Positive and sustained effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy on HIV-1-associated neurocognitive impairment. AIDS. 1999;13:1889–97. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199910010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sidtis JJ, Gatsonis C, Price RW, et al. Zidovudine treatment of the AIDS dementia complex: results of a placebo-controlled trial. AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Ann Neurol. 1993;33:343–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brew BJ, Dunbar N, Druett JA, et al. Pilot study of the efficacy of atevirdine in the treatment of AIDS dementia complex. AIDS. 1996;10:1357–60. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199610000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Canestri A, Lescure FX, Jaureguiberry S, et al. Discordance between cerebral spinal fluid and plasma HIV replication in patients with neurological symptoms who are receiving suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:773–8. doi: 10.1086/650538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Al-Khindi T, Zakzanis KK, van Gorp WG. Does antiretroviral therapy improve HIV-associated cognitive impairment? A quantitative review of the literature. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2011;17:1–14. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711000968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cysique LA, Brew BJ. Neuropsychological functioning and antiretroviral treatment in HIV/AIDS: a review. Neuropsychol Rev. 2009;19:169–85. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Joska JA, Gouse H, Paul RH, et al. Does highly active antiretroviral therapy improve neurocognitive function? A systematic review. J Neurovirol. 2010;16:101–14. doi: 10.3109/13550281003682513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liner KJ, Hall CD, Robertson KR. Effects of antiretroviral therapy on cognitive impairment. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2008;5:64–71. doi: 10.1007/s11904-008-0011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tozzi V, Balestra P, Liberstone R, et al. Cognitive function in treated HIV patients. Neurobehav HIV Med. 2010;2:95–113. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors. J Neurovirol. 2011;17:3–16. doi: 10.1007/s13365-010-0006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vivithanaporn P, Heo G, Gamble J, et al. Neurologic disease burden in treated HIV/AIDS predicts survival: a population-based study. Neurology. 2010;75:1150–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f4d5bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cysique LA, Letendre SL, Ake C, et al. Incidence and nature of cognitive decline over 1 year among HIV-infected former plasma donors in China. AIDS. 2010;24:983–90. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833336c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Marcotte TD, Deutsch R, McCutchan JA, et al. Prediction of incident neurocognitive impairment by plasma HIV RNA and CD4 levels early after HIV seroconversion. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1406–12. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.10.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McArthur JC, Steiner J, Sacktor N, Nath A. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Mind the gap. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:699–14. doi: 10.1002/ana.22053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Letendre SL, Ellis R, Ances B, McCutchan J. Neurologic complications of HIV disease and their treatment. Top HIV Med. 2010;18:45–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Letendre S, FitzSimons C, Ellis R, et al. San Francisco, CA: 2010. Correlates of CSF viral loads in 1,221 volunteers of the CHARTER cohort. 17th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, 16–19 February Abstract 172. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Letendre SL, McCutchan JA, Childers ME, et al. Enhancing antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus cognitive disorders. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:416–23. doi: 10.1002/ana.20198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Spudich S, Lollo N, Liegler T, Deeks SG, Price RW. Treatment benefit on cerebrospinal fluid HIV-1 levels in the setting of systemic virological suppression and failure. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1686–96. doi: 10.1086/508750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McClernon D, Letendre S, Benjamin R, et al. Low-level HIV-1 viral load monitoring in cerebral spinal fluid: possible correlation to antiviral drug penetration. 2007 EACS poster: P6.11/101 Available at: http://www.abstractserver.com/eacs2007/oaa/documents/P6.11-01_1.pdf. Accessed 25 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Letendre S, McClernon D, Ellis RJ, et al. Persistent HIV in the central nervous system during treatment is associated with worse antiretroviral therapy penetration and cognitive impairment. 2009 16th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Montreal, Canada, 8–11 February Poster 484b. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Robertson KR, Su Z, Margolis DM, et al. Neurocognitive effects of treatment interruption in stable HIV-positive patients in an observational cohort. Neurology. 2010;74:1260–6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d9ed09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Childers ME, Woods SP, Letendre S, et al. Cognitive functioning during highly active antiretroviral therapy interruption in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Neurovirol. 2008;14:550–7. doi: 10.1080/13550280802372313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Muñoz-Moreno JA, Funaz CR, Prats A, et al. Interruptions of antiretroviral therapy in human immunodeficiency virus infection: are they detrimental to neurocognitive functioning? J Neurovirol. 2010;16:208–18. doi: 10.3109/13550281003767710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.El-Sadr WM, Lundgren JD, Neaton JD, et al. CD4+ count-guided interruption of antiretroviral treatment. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2283–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Danel C, Moh R, Minga A, et al. CD4-guided structured antiretroviral treatment interruption strategy in HIV-infected adults in west Africa (Trivacan ANRS 1269 trial): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;367:1981–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ruiz L, Paredes R, Gómez G, et al. Antiretroviral therapy interruption guided by CD4 cell counts and plasma HIV-1 RNA levels in chronically HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS. 2007;21:169–78. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328011033a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Clifford DB, Evans S, Yang Y, Acosta EP, Ribaudo H, Gulick RM A5097s Study Team. Long-term impact of efavirenz on neuropsychological performance and symptoms in HIV-infected individuals (ACTG 5097s) HIV Clin Trials. 2009;10:343–55. doi: 10.1310/hct1006-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ciccarelli N, Fabbiani M, Di Giambenedetto S, et al. Efavirenz associated with cognitive disorders in otherwise asymptomatic HIV-infected patients. Neurology. 2011;76:1403–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821670fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Poeta J, Linden R, Antunes MV, et al. Plasma concentrations of efavirenz are associated with body weight in HIV-positive individuals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2601–4. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kappelhoff B, van Leth F, Robinson P, et al. Are adverse events of nevirapine and efavirenz related to plasma concentrations? Antivir Ther. 2005;10:489–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hoffman C, Rockstroh J, Kamps BS. HIV medicine. 15th ed. 2007. Paris, Cagliari, Wuppertal: Flying Publisher Available at: http://hivmedicine.com/textbook/download.htm. Accessed 25 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Uthman OA, Abdulmalik JO. Adjunctive therapies for AIDS dementia complex. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16:CD006496. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006496.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kodl CT, Seaquist ER. Cognitive dysfunction and diabetes mellitus. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:494–511. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Foley J, Ettenhofer M, Wright MJ. Neurocognitive functioning in HIV-1 infection: effects of cerebrovascular risk factors and age. Clin Neuropsychol. 2010;24:265–85. doi: 10.1080/13854040903482830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ellis RJ, Badiee J, Vaida F, et al. Nadir CD4 is a predictor of HIV neurocognitive impairment in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2011;25:1747–51. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834a40cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Duara R, Loewenstein DA, Greig MT, et al. Pre-MCI and MCI: neuropsychological, clinical, and imaging features and progression rates. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:951–60. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182107c69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]