Abstract

There is a critical need for new pathways to develop antibacterial agents to treat life-threatening infections caused by highly resistant bacteria. Traditionally, antibacterial agents have been studied in noninferiority clinical trials that focus on one site of infection (eg, pneumonia, intra-abdominal infection). Conduct of superiority trials for infections caused by highly antibiotic-resistant bacteria represents a new, and as yet, untested paradigm for antibacterial drug development. We sought to define feasible trial designs of antibacterial agents that could enable conduct of superiority and organism-specific clinical trials. These recommendations are the results of several years of active dialogue among the white paper's drafters as well as external collaborators and regulatory officials. Our goal is to facilitate conduct of new types of antibacterial clinical trials to enable development and ultimately approval of critically needed new antibacterial agents.

This white paper provides recommendations on clinical trial designs to determine if investigational antibacterial agents are superior in efficacy to approved agents for the treatment of infections caused by highly drug-resistant bacterial pathogens. For the last several decades, substantial ethical and practical barriers have hindered the conduct of superiority studies of antibacterial agents. Meanwhile, bacterial pathogens are increasingly antibacterial-resistant, with some pathogens—particularly gram-negative bacilli (GNB)—resistant to all or nearly all antibacterial agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [1–7]. Examples of such infections that many hospitals are now struggling with include those caused by carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In addition, some community-acquired infections caused by Enterobacteriaceae are increasingly resistant to all approved orally administered antibiotics, putting patients at risk for failing therapy with outpatient oral antibiotics, with possible severe consequences of progressive infection. It is increasingly necessary to admit such patients to the hospital solely to administer parenteral antibacterial therapy, which places these patients at risk for hospital-acquired and/or catheter-associated complications that would be avoided if effective oral therapy was available for their infections. Most recently, penicillin/ceftriaxone-, fluoroquinolone-, and macrolide-resistant strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae have been described, raising the specter of untreatable gonorrhea [8–11]. The development of new antibacterial agents with activity against such resistant pathogens is a significant unmet medical need. Because currently available therapy is not adequately effective for such infections, it is not meaningful to establish that experimental therapy is similarly ineffective. Thus, superiority clinical trials are needed to support development of new antibiotics to treat the most problematic resistant pathogens. Since resistance patterns are constantly evolving among clinically relevant bacteria, the principles discussed herein for highly antibiotic-resistant aerobic gram-negative bacteria are relevant to other pathogens that are likely to develop resistance to most classes of antimicrobials in the future.

Conduct of superiority trials for infections caused by highly antibiotic-resistant bacteria represents a new and as yet untested paradigm for antibacterial drug development that presents unique challenges. For example, patients who develop life-threatening infections due to highly resistant GNB are often extremely ill, require intensive adjunctive care, and have multiple comorbid diseases. Enrolling these patients poses several ethical and practical challenges. Studies are likely to be global and conducted in regions with differing standards of care, approved comparator drugs, and regulatory benchmarks; thus, protocol development requires careful attention to harmonization. Furthermore, once a new antibacterial agent is established as superior in efficacy for the treatment of a specific infection, it will become the standard comparator for future antibacterial agents studied for the same infection, including in noninferiority trials. Thus, the conduct of superiority trials will likely be applicable only to a limited spectrum of infections, which may change over time as new antibacterial agents are approved and bacterial resistance profiles change. Our goal in facilitating the conduct of superiority clinical trials is not to replace noninferiority studies, which have a proven role in demonstrating efficacy and safety of antimicrobial drugs for a number of indications. Rather, our goal is to complement traditional noninferiority studies by facilitating establishment of feasible trial designs that can lead to approval for antibacterial agents based on superiority studies for infections with limited available therapeutic options.

ETHICAL BARRIERS TO CONDUCT OF SUPERIORITY STUDIES FOR ANTIBACTERIAL AGENTS

The availability of marketed agents with established efficacy for the treatment of infections caused by GNB [12–16] precludes conduct of placebo-controlled trials for these infections. Furthermore, active-controlled superiority studies of antibacterial agents are ethical to conduct only if (1) the control (ie, the comparator drug) is active against most, or all, of the bacterial strains likely to be encountered in the study; (2) all available drugs that could be used as comparators for the study are inadequately active against the strains likely to be encountered, such that there is no alternative effective therapy possible; or (3) the infection under study is almost universally nonfatal, such that rescue therapy can be instituted rapidly enough to preclude serious sequelae upon recognition that the strain causing the infection is resistant to the comparator drug (eg, uncomplicated urinary tract infection [UTI]).

The susceptibility of etiologic bacteria is almost never known at the time an infected patient is enrolled in a clinical trial that evaluates initial antimicrobial treatment. Therefore, the comparator drugs chosen for study in antibacterial clinical trials are selected because they are anticipated to be effective against all, or almost all, strains likely to be encountered during conduct of the study. Yet, antibacterial therapy is generally so effective when treating infections caused by susceptible bacteria, it is unlikely that investigational therapy can achieve superiority to a marketed comparator drug when the infections under study are susceptible to both drugs.

Thus, while the primary complexities of designing noninferiority clinical trials of antibacterial agents are statistical in nature [17], the primary barriers to conduct of superiority studies of antibacterial agents are practical. Specifically, how does one design a study in which superiority realistically can be expected to be demonstrated while adhering to appropriate ethical standards (ie, without intentionally withholding available effective therapy)? In addition, how does one enroll patients who are critically ill and have decreased ability to consent for study participation?

OVERCOMING PRACTICAL BARRIERS TO THE CONDUCT OF SUPERIORITY STUDIES

General Design Options

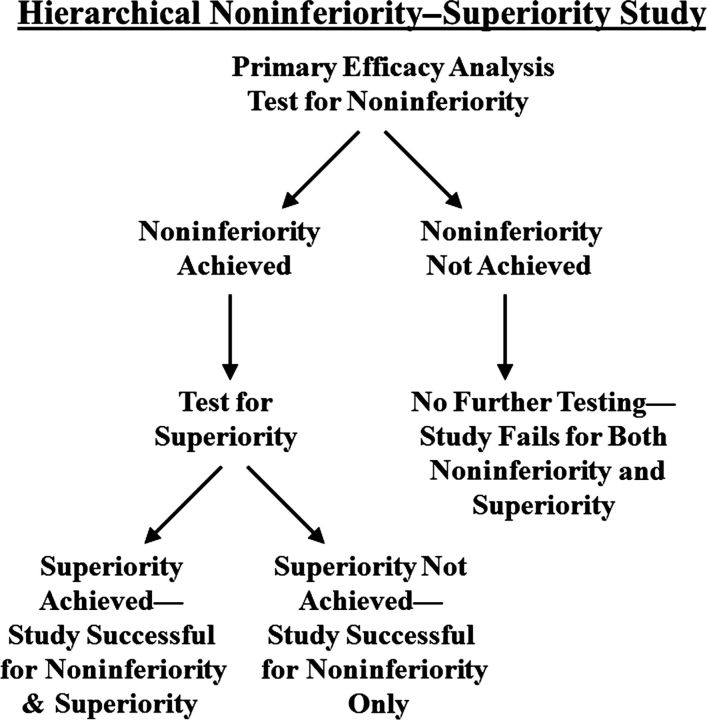

Hierarchical Noninferiority–Superiority Clinical Trials

A noninferiority trial that includes a hierarchical, superiority, primary efficacy analysis is the simplest type of trial design for a superiority study of antibacterial agents for the treatment of infections caused by GNB (Figure 1). A hierarchical analysis enables sequential endpoint testing while avoiding the statistical penalties associated with multiple comparisons [18, 19]. The first analysis conducted in this trial design is for determination of noninferiority. Only if noninferiority is established by the primary efficacy analysis can a second analysis for superiority be conducted without requiring adjustment of the significance level for multiple comparisons. By using a hierarchical analysis, a sponsor can test for superiority to the comparator drug during conduct of a noninferiority trial. Thus even if superiority is not found, noninferiority can be established, mitigating the practical concerns about feasibility of detecting superiority. However, the trial would have to be powered for achievement of noninferiority, with appropriately justified noninferiority margins. Furthermore, if the trial uses a comparator drug that is active against most or all bacterial strains encountered, the probability of achieving superiority is small, and in this circumstance, the study may not differ substantively from a standard noninferiority study. Nevertheless, the recent example of the successful, hierarchical noninferiority–superiority clinical trial comparing linezolid to vancomycin for the treatment of healthcare-associated pneumonia caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus demonstrates the potential utility of this design [20].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of a hierarchical noninferiority–superiority study.

Monotherapy Superiority Clinical Trials

Less Severe Infections With Possible Rescue Therapy

It may be ethical and feasible to study the potential superiority of an investigational antibacterial agent to a comparator drug in a trial of a disease caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria that have a very low likelihood of causing severe morbidity or mortality if definitive therapy is delayed. An example is a trial enrolling patients with an uncomplicated UTI (eg, cystitis in the absence of urinary tract obstruction) in the epidemiological setting of a high incidence of resistance to the current standard-of-care oral treatments. The rising incidence of resistance of community strains of Escherichia coli, and other GNB, to oral antibacterial therapy creates an opportunity for a superiority trial design. Patients with community-onset, or catheter-associated, uncomplicated UTIs caused by organisms resistant to all oral antibiotics (including fosfomycin) would be an appropriate study population, given the relatively low risk of severe complications and the feasibility of following study patients closely and offering rescue therapy when appropriate. In addition, the alternative treatment option for such infections is hospitalization with administration of parenteral therapy, with the risks attendant therein. Thus, a sound risk-benefit argument can be made for conduct of such a study given the low risk of harm from uncomplicated UTI during the first several days even with relatively ineffective comparator oral therapy weighed against the risk of harm from requiring alternative, daily parenteral comparator therapy. Another example of possible monotherapy superiority trials in which rescue therapy could be employed is gonorrhea caused by bacterial isolates resistant to ceftriaxone and fluoroquinolones.

Conduct of such a superiority study requires identification of investigative sites with a particularly high incidence of infections due to the target resistant pathogen, and would be greatly facilitated by availability of molecular diagnostic studies that could rapidly identify patients infected with the target pathogens. The primary efficacy analysis in a superiority study of uncomplicated UTI includes both resolution of signs and symptoms of infection, as well as microbiological eradication of GNB from the urine at end of therapy (ie, day 3). Mortality should also be evaluated to ensure there is no important imbalance between therapeutic groups. In this example, each patient would submit a urine culture prerandomization, and those who have persistent symptoms at the primary efficacy analysis (ie, day 3) would receive rescue therapy (parenterally, if necessary). Because it typically takes 2–3 days to determine the susceptibility profile of an etiologic agent, the primary efficacy analysis at day 3 occurs before initiation of salvage therapy, and hence salvage therapy does not impact the primary outcome measure.

Trials of Extreme Drug-Resistant and Pandrug-Resistant Infections

If all available therapies are inadequately effective or unacceptably toxic, superiority of an investigational agent to the comparator agent is ethical to study, since available effective therapy is not being denied to patients. Thus superiority studies are ethical and practical to conduct if the etiological organisms studied are extreme drug resistant (XDR) or pandrug resistant (PDR). In concordance with a recent international consensus definition [21], we define PDR organisms as those resistant to all FDA-approved, systemically active antibacterial agents. We define XDR organisms differently than extensively drug-resistant organisms as defined in the previous consensus document [21] (hence our use of the term “extreme drug-resistant” rather than “extensively drug-resistant”). For the purpose of planning superiority clinical trials, we define XDR organisms as those resistant to all FDA-approved, systemically active antibacterial agents except for those known to be substantially more toxic than or inferior in efficacy to alternative agents when used to treat susceptible organisms. For example, currently GNB resistant to all FDA-approved antibacterial agents except for aminoglycosides, tigecycline, or polymyxin B or E (ie, colistin) meet the definition of XDR. These agents are known to be relatively ineffective and nephrotoxic (aminoglycosides and polymyxins), resulting in outcomes inferior to those of other antibacterial agents when used as monotherapy to treat non-XDR/PDR GNB infections [3, 22–36]. The profile of resistance for organisms necessary to meet the definition of XDR and PDR will change over time, as new agents become available for treatment and resistance patterns change among bacterial pathogens. Hence, sponsors seeking to conduct superiority studies of antibacterial agents for the treatment of infections caused by XDR and/or PDR bacteria should justify the definition of XDR/PDR bacteria in the context of the planned study.

One potential approach to enrich the population in such a trial with resistant gram-negative organisms is by incorporating inclusion criteria that are known to predict a highly resistant organism. Risk factors that predict a highly drug resistant organism include previous hospitalization in the preceding 90 days, receipt of parenteral antibiotics in the preceding 90 days, and residence in a nursing home or long-term care facility.

Analysis of composite efficacy endpoints that incorporate clinically important toxicity measures may facilitate achievement of statistical superiority when studying investigational drugs that have a more favorable safety profile. For example, polymyxin E/colistin is known to be nephrotoxic, and patients who survive their infections but with substantial nephrotoxicity have had meaningfully inferior outcomes compared to patients who survive with preserved renal function. Therefore, an investigational antibacterial agent with efficacy against such XDR/PDR organisms has a particularly promising chance to achieve superiority to the comparator regimens if meaningful toxicities that are common with comparator drugs but not the experimental agent are incorporated into a primary efficacy endpoint.

In some cases, a primary safety endpoint may be possible, for example, when the only acceptable alternative is a drug with known toxicity such as an aminoglycoside or colistin. Such studies could be powered for safety outcomes with analyses of efficacy employed as secondary endpoints. As with efficacy studies, enabling studies that demonstrate in vitro and in vivo efficacy, as well as dose rationale and justification, would be requisite.

The investigational regimen in a monotherapy superiority study requires evidence of efficacy for XDR/PDR pathogens from preclinical data and phase 1/2 clinical trials. Such evidence will take the form of proven in vitro and animal in vivo activity, appropriate understanding of pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic exposure-response relationships, and confirmation that antibacterial activity is effective at the site(s) of infection (eg, central nervous system, lung) in sufficient concentrations for in vivo activity.

The a priori hypothesis of efficacy of the investigational drug for treating infections caused by XDR/PDR pathogens raises questions about the ethics of randomizing patients in a pivotal study to the chance of treatment with an ineffective standard comparator regimen. However, a superiority study is ethical in this situation because (1) the safety profile of the investigational drug is not established, whereas the safety profile of the comparator regimen is established; and (2) the efficacy of the investigational regimen is possible, but not yet definitively established. Such trials should be closely monitored by independent data safety monitoring boards [37], so they are not continued beyond the point required to demonstrate superiority, or a point at which lack of efficacy or presence of toxicity is demonstrated.

Empiric or Targeted Enrollment for Superiority Studies?

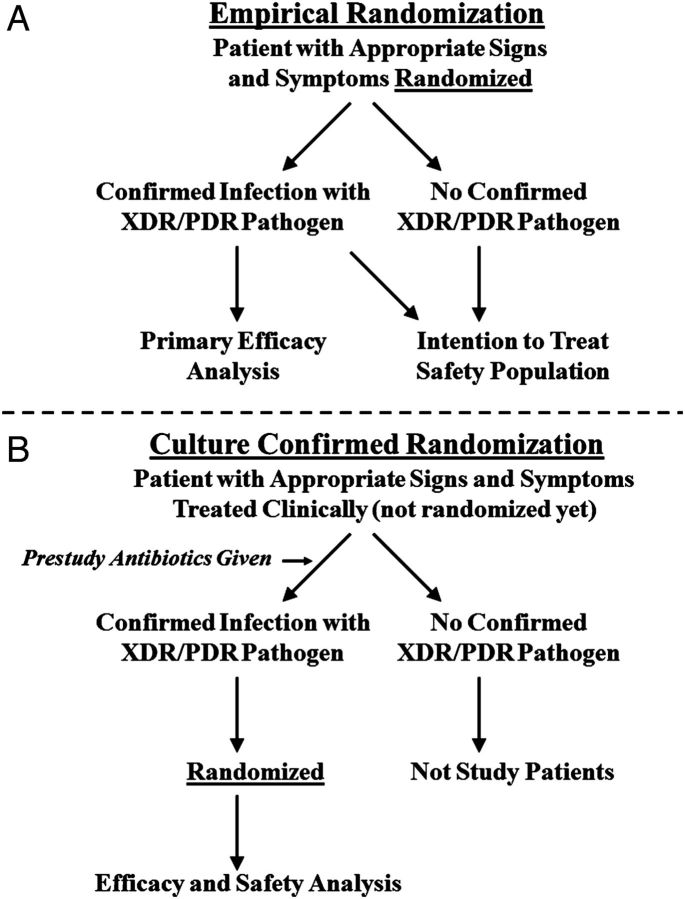

A critical question regarding the design of a superiority trial of antibacterial therapy for infections caused by resistant GNB is whether patients can be randomized prior to availability of culture results (Figure 2A), or only after they are known to be infected by the target resistant organism(s) (Figure 2B). Either approach may be acceptable, but the advantages and disadvantages of each should be carefully considered by the sponsor prior to study initiation.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram depicting trial designs based on randomization before or after knowing the infecting pathogen. Abbreviation: XDR/PDR, extreme drug resistant/pandrug resistant.

If patients are randomized prior to culture results, such that the specific etiologic organism(s) is not known, the primary efficacy analysis population should be predefined as only those patients who are subsequently confirmed to be infected with an XDR or PDR GNB. All other subjects are analyzed only for safety, and possibly in a separate noninferiority study (see nested superiority–noninferiority trial design below). In this scenario, the microbiological samples by which the target pathogens are identified should be sent for testing prior to patient randomization, to ensure that no postrandomization events can affect the test results. This approach has several advantages. First, the trial design reproduces and is relevant to standard clinical practice, where initial empiric therapy is almost always selected in the absence of culture and susceptibility data. Second, the design minimizes the use of nonstudy antibacterial therapy prior to patient enrollment, which could confound differences in outcomes between the 2 study groups. Third, this approach results in the earliest initiation of investigational therapy, minimizing the duration of treatment with ineffective therapy, and thereby maximizing the likelihood of detection of true superiority of the investigational agent for infections caused by XDR/PDR infections. Fourth, the randomization of substantial numbers of patients who are not subsequently included in the primary efficacy analysis population generates a safety database. Note that if the patient's culture comes back negative for the target pathogen(s), there are 2 options. The first is to discontinue the patient from study medication and start them on standard of care medication. The second is to continue the patient on study medications to build a more sizable safety database. In the former design, the safety data for such patients will be relevant to patients empirically started and then discontinued on such therapy postmarketing, rather than relevant to the full duration of treatment to complete a course of therapy.

Randomizing patients prior to microbiological confirmation creates a specific potential problem in studies designed to analyze for efficacy only patients confirmed to be infected by the target pathogens. Specifically, random imbalances can occur between the proportions of the patients enrolled in the 2 study arms that are subsequently found to have confirmation of the target pathogen. This risk of imbalances in confirmation of the target pathogen(s) could be substantial for small studies, with resulting bias. However, the risk of imbalance is mitigated by increasing the study size, which reduces variance and hence the likelihood that by random chance more patients in one arm are confirmed to be infected by target pathogens. We emphasize that this subgroup problem is distinct from that which occurs when evaluating a per protocol population, as postrandomization events affect subgroup determination in the latter setting. In contrast, the results of microbiological tests obtained prerandomization cannot be affected by any postrandomization event.

There are also advantages of randomizing patients only after establishing that the infection is caused by the targeted XDR/PDR GNB. For example, targeted randomization after identifying an XDR or PDR GNB would require a smaller number of patients to be randomized. As well, the evaluable population is fully protected by randomization. The major disadvantage is that substantial prerandomization, nonstudy antibacterial therapy occurs and complicates interpretation of the relative efficacy of the investigational and comparator drugs. This limitation may be mitigated if the prestudy therapy is clinically and microbiologically inactive against the targeted XDR/PDR GNB. However, delay in initiation of active therapy of even 24–48 hours results in a substantial increase in mortality of patients with severe infections, such as sepsis, community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia (HABP), and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia (VABP) [38–42]. If prestudy therapy is inactive against the targeted XDR/PDR GNB, the resulting delay in initiation of effective therapy could increase mortality even for patients who subsequently receive effective investigational therapy. Thus, randomization of patients after confirmation that the infection is due to the target XDR/PDR GNB may reduce the potential for detection of a true superiority of the investigational regimen by reducing the treatment effect size. The study power to detect a decreased treatment effect size can be compensated by increasing the sample size, but the sample size would likely have to be much larger, and it is difficult to predict what effect prestudy therapy would have on the treatment effect size. Another disadvantage of randomization of patients with confirmed XDR/PDR GNB is that the safety population is substantially smaller than if patients are randomized at the empiric stage. This limitation can be mitigated by studying larger groups of patients with other infections for safety, as well as requiring substantial postapproval active safety surveillance or additional safety studies.

Ultimately, the availability of rapid molecular diagnostic tests that can accurately identify the target pathogens, and perhaps even the presence of drug-resistance genes, either before randomization or shortly after randomization provides the optimal solution to determining which patients to randomize and which to analyze for efficacy. Use of such tests enables conduct of a superiority test in which only patients who are known to have the target organism are enrolled before receipt of prolonged nonstudy antibacterial therapy.

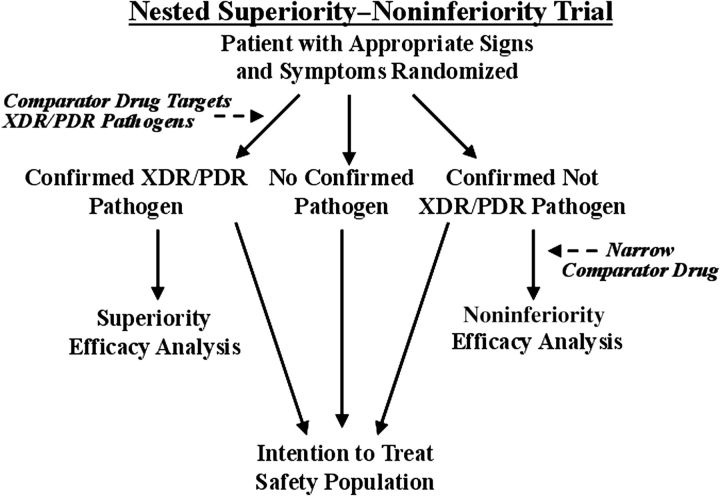

Nested Superiority–Noninferiority Trial Design

In the absence of rapid diagnostic tests that identify targeted XDR/PDR pathogens, another acceptable design combines the empiric and confirmed target organism approaches into a nested superiority–noninferiority study (Figure 3). The nested design randomizes patients at the time of empiric antibacterial therapy. Patients subsequently confirmed to be infected with the targeted XDR/PDR GNB are included as a distinct analysis population for superiority. Patients infected with non-XDR/PDR pathogens are included in a cohort for analysis of noninferiority. For the superiority analysis, the primary efficacy population is the microbiological intention-to-treat (MITT) population, which consists of all randomized patients who are confirmed to have infection caused by XDR/PDR pathogens. The pathogen will be defined by pathogenic potential plus recovery from the infected site or blood; with mixed cultures (exudates, etc), the pathogen will be defined by the presence of large concentrations (eg, ≥105/mL or ≥3rd streak on conventional agar media).

Figure 3.

Flow diagram of a nested superiority–noninferiority trial. Abbreviation: XDR/PDR, extreme drug resistant/pandrug resistant.

For the noninferiority subtrial, the primary efficacy population is the modified MITT population, who have received at least 1 dose of study drug and who have a confirmed bacterial infection caused by a non-XDR/PDR pathogen. For both the superiority and noninferiority subtrials, microbiological confirmation should be based on microbiological tests that are obtained prior to patient randomization to protect the test results from postrandomization events. The combined safety population consists of all randomized patients receiving study drug, including patients who did not have confirmation of bacterial etiology of infection, increasing the size of the safety dataset.

For a nested superiority–noninferiority trial, the empiric therapy selected upon randomization should be broad enough to have predictable activity against XDR GNB, which may be responsible for the infection. For example, currently such therapy might include an aminoglycoside, tigecycline, or polymyxin B or E, likely in addition to an agent that is more effective for treating non-XDR GNB. If the etiological organism is not an XDR/PDR pathogen and the patient is moved into the noninferiority subtrial, the comparator antibacterial regimen could be changed/narrowed to an agent that is effective against most non-XDR/PDR pathogens encountered in the trial. Such a trial should enroll at investigative sites with a high frequency of XDR/PDR pathogens.

In planning the sample size for a nested superiority–noninferiority study, the sponsor should consider adequate study power for both the superiority and noninferiority subtrials. Depending on the specific public health need for an antibacterial agent with superior efficacy against a clinically important subset of XDR/PDR organisms, it may be possible for the sponsor to justify a wider than usual margin for noninferiority for the investigational agent in the treatment of non-XDR/PDR pathogens, as long as superiority is confirmed against XDR/PDR pathogens in the superiority subtrial.

Combination Superiority Clinical Trials

Use of adjunctive therapy to improve outcomes of infection is another trial design in which superiority testing of antibacterial agents for the treatment of GNB infections can be evaluated. Such a study compares standard-of-care therapy (which may consist of a standard combination or monotherapy regimen) plus the investigational adjunctive agent versus standard-of-care therapy plus placebo. The comparator group regimen includes placebo in addition to standard-of-care therapy to enable blinding of the study. Note that “standard-of-care therapy” does not imply that it is selected at the discretion of the individual investigator; rather the standard-of-care therapy regimen, or the process for choosing it, should be defined a priori in the study protocol and generally in agreement with contemporary guidelines from authoritative sources.

The addition of a new antibacterial agent to an existing regimen to improve outcome of infection is only testable in a superiority study. For example, this design is often used in the study of drugs for salvage therapy of human immunodeficiency virus infection. The goal is to assess superiority; achievement of noninferiority in that setting does not constitute evidence of efficacy of the new agent. Some examples of new adjunctive agents that would be appropriate to test in addition to standard-of-care therapy are (1) inhalational agents targeting XDR/PDR organisms; (2) new systemic agents with spectra of activity focusing on XDR/PDR organisms; (3) new agents that are synergistic with existing agents and hence result in superior in vitro killing of GNB; (4) immunomodulatory adjunctive therapy; or (5) biological agents (eg, antitoxin or antibacterial pathogenesis factors, or devices that remove such factors).

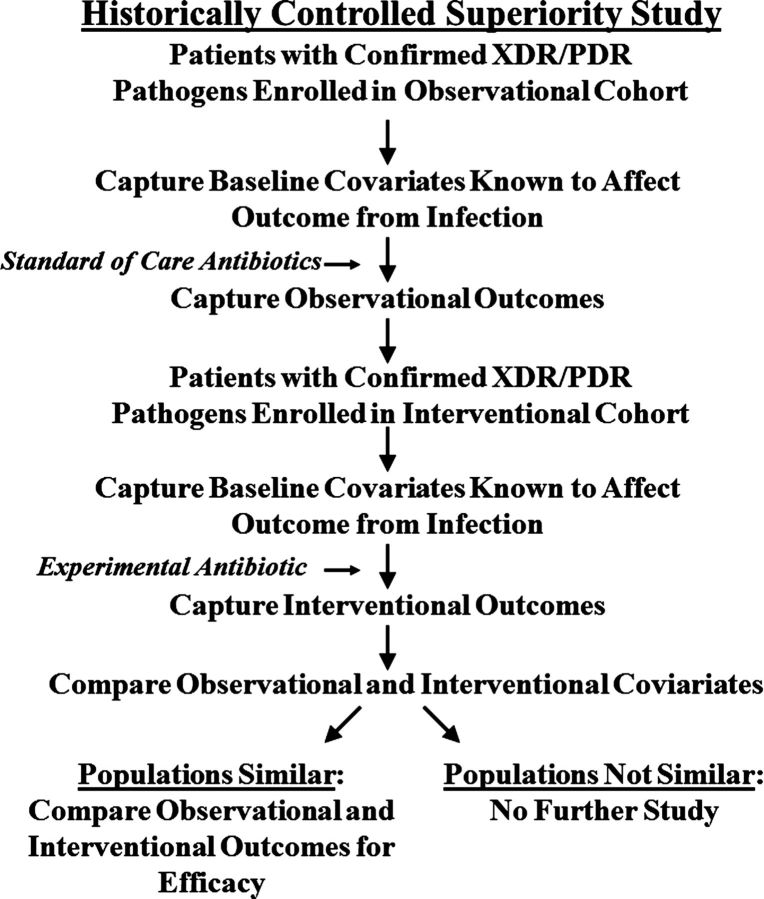

Historically Controlled Superiority Studies

An assessment based on the use of historical control data is unlikely to prove as robust as conclusions based on contemporary controlled trials. Nonetheless, in some circumstances historical data can be used to efficiently and ethically support clinical conclusions. The possibility of historically controlled superiority clinical trials is explicitly discussed in the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) E10 guidance, which states that “[i]n unusual cases … it may be possible to use a similar group of patients previously studied as a historical control” for clinical trials [43]. The guidance emphasizes that if a historical control group is used for a clinical trial, the controls should be selected from a “well documented population of patients … on the basis of particular characteristics that make them similar to the treatment group” [44]. The guidance continues, “The inability to control bias restricts use of the [historical] control design to situations in which the effect of treatment is dramatic and the usual course of the disease highly predictable. In addition, use of [historical] controls should be limited to cases in which the endpoints are objective and the impact of baseline and treatment variables on the endpoint is well-characterized” [44].

The poor outcomes of systemic infections caused by XDR/PDR GNB enable potential use of historical controls for a clinical trial of an investigational antibacterial agent with activity against such pathogens, consistent with the ICH E10 guidance (Figure 4), which specifies that

[historically] controlled trials are most likely to be persuasive when the study endpoint is objective, when the outcome on treatment is markedly different from that of the external control and a high level of statistical significance for the treatment-control comparison is attained, when the covariates influencing outcome of the disease are well characterized, and when the control closely resembles, or “matches,” the study group in all known relevant baseline, treatment (other than study drug), and observational variables. [45]

Figure 4.

Flow diagram of a historically controlled superiority trial. Abbreviation: XDR/PDR, extreme drug resistant/pandrug resistant.

Prospective establishment of a robust and well-characterized observational cohort of patients with infections caused by XDR or PDR GNB would fulfill the rigorous criteria specified in the ICH E10 guidance document regarding historically controlled studies. For example, such a database could be constructed by enrolling the prospective observational cohort that is to serve as the historical control immediately proximate to, or concurrent with (possibly at distinct trial sites), initiation of the investigational group of the study. The patients ultimately enrolled into the investigational group would have to be demonstrably similar to the observational cohort that served as the historical controls. Specific matching methods, such as by propensity analysis, are encouraged to improve matching of control and interventional cohorts based on known key parameters. Prespecified analysis of the baseline patient characteristics, validated risk factors, and covariates that are known to predict morbidity and/or mortality should be planned between the historical controls and the investigational group to validate the similarity of the populations. The investigational group most likely would receive open-label administration of the investigational drug. The prespecified primary efficacy outcome of the study most likely would be all-cause mortality as the most objective measure. The investigational group would be tested for superiority against the historical controls. In circumstances where the mortality rate of the infection is low despite being caused by XDR/PDR bacteria, it may be possible to consider using a nonmortality endpoint as long as the endpoint selected is strictly objective, reflects a clinically important outcome, and can be measured precisely.

Pharmacometric Approach to Defining Historical Control Response Rates

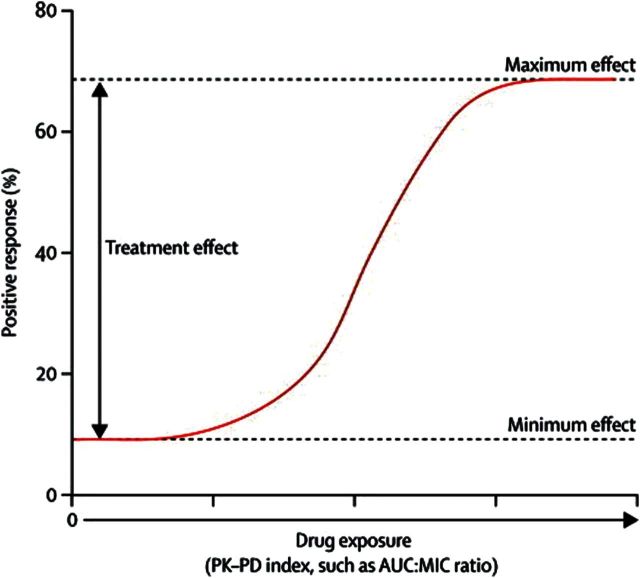

The pharmacometric approach uses the relationship between drug exposure and response to estimate the magnitude of treatment effect of active versus inactive therapy [46]. For an antimicrobial agent, drug exposure is usually indexed to a measure of drug potency (eg, the ratio of the area under the free drug plasma concentration-time profile to the minimum inhibitory concentration of the drug to the pathogen [fAUC:MIC ratio]). The functional relationship between drug exposure and response can take any one of several shapes, but is most commonly described by a sigmoid or logistic function. The magnitude of treatment effect is the difference in response at high and low drug exposures (Figure 5). Thus, outcomes in patients with the lowest drug exposures can provide an estimate of historical control efficacy (ie, a placebo-response rate). That is, as drug exposure approaches zero, the associated response is an estimate of the placebo response (Figure 5) [47]. Thus, using pharmacometrics, it is possible to estimate a placebo response from a contemporary clinical trial dataset as a historical control efficacy estimate. This approach eliminates the need to enroll a new cohort of patients to serve as historical controls.

Figure 5.

Relationship between drug exposure and response to therapy. The treatment effect is the difference between maximum and minimum drug effect. The y-intercept of the functional relationship between exposure and response is an estimate of the placebo response. Abbreviations: PK-PD, pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics; AUC:MIC, area under the curve–minimum inhibitory concentration ratio. Figure adapted from Ambrose PG, et al, Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12:265–6.

There are several issues that need careful consideration when using the pharmacometric approach to evaluate the efficacy of a new drug versus antibiotic-resistant pathogens. For instance, because of the relative rarity of the specific infection(s) being studied, and/or the narrow spectrum of the new drug, the proposed study may necessitate that patients with different clinical syndromes (eg, VABP, complicated UTI) be enrolled in the same study. In such a case, data across the relevant indications may be pooled and the specific indication used as a covariate in the pharmacometric analysis. In this way, one can understand the impact of an individual clinical indication on the functional relationship between drug exposure and response.

Potential Use of Emergency Exception to Informed Consent

A practical limitation to conduct of superiority clinical trials for infections caused by GNB is the difficulty in obtaining informed consent from critically ill patients. When studying such patients, altered mental status and severe physiological derangements (eg, the need for mechanical ventilation or high-flow oxygen supplementation) often preclude obtaining informed consent. Furthermore, there is typically time urgency to administer effective therapy for seriously ill patients, which may preclude obtaining informed consent from family members. To overcome these limitations, in some circumstances it may be appropriate to request an exception from institutional review boards to obtain informed consent. The criteria for an exception are set forth in the federal regulation for “Exception from informed consent requirements for emergency research” (21 CFR Part 50.24) [48].

Infections caused by XDR and PDR bacteria, for which there is no effective or only relatively ineffective antibacterial therapy, meet the criteria specified in 21CFR50.24. The observed mortality rate increases by 5% for every hour delay after onset of hypotension before instituting effective antibacterial therapy [41]. Therefore, substantial time pressure does exist in this setting, which would preclude delaying longer than a few minutes to obtain informed consent, since sufficient time is needed to complete all postrandomization events prior to initiating infusion of the investigational agent.

Identifying Sufficient Patients to Complete Enrollment

The present relatively low frequency of highly resistant XDR/PDR infections as compared with infections due to less resistant pathogens in populations suitable for study in clinical trials is a practical limitation to conduct of superiority studies for GNB. It may be difficult to identify and enroll sufficient numbers of patients to complete enrollment of large-scale, pivotal phase 3 trials (Table 1). Sponsors may wish to consider 3 strategies to mitigate this limitation: (1) the conduct of organism-specific trials in which patients with one of several infection sites are enrolled in the same study, broadening the population eligible for enrollment; (2) the acceptability of smaller clinical development programs to support regulatory approval of drugs that address an unmet public health need; and (3) the use of statistical methods, such as adaptive Bayesian trial design, to maximize the information derived from limited patient populations (as discussed in recent FDA guidances on the use of Bayesian methods for trials of medical devices [49] and on adaptive clinical trial design for drugs and biologics [50]).

Table 1.

Sample Sizes for Superiority Studies by Expected Superiority Ratesa

| Success Rate With Comparator Therapy (%) | Absolute Difference in Success Rate (Experimental – Comparator) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | 20% | 30% | 40% | |

| 30 | 952 | 248 | 112 | 62 |

| 40 | 1036 | 258 | 112 | 58 |

| 50 | 1036 | 248 | 102 | 50 |

| 60 | 952 | 216 | 84 | 40 |

| 70 | 784 | 164 | 62 | N/A |

| 80 | 532 | 106 | N/A | N/A |

a Assumes 90% trial power at an α of .05. Numbers shown are totals for both arms. For example, if the success rate in the control arm is 50%, and the success rate is 80% with experimental therapy (absolute difference 30%), the sample size is only 102 patients total.

Organism-Specific Superiority Clinical Trials

In the recent past, indications for antibacterial agents have been granted by the FDA for specific infectious disease clinical syndromes, for example, CAP, complicated skin and skin structure infections (now referred to as acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections), HABP, and VABP. However, there is a clear public health need for new antibacterial agents to treat infections resulting from multidrug-resistant bacterial infections, irrespective of where those infections occur in the body.

In contrast to antibacterial agents, systemic antifungal agents are approved for the treatment of invasive infection caused by specific fungi, rather than by disease state. For example, a number of drugs are approved for the treatment of invasive candidiasis or invasive aspergillosis. These antifungal indications encompass invasive infection of a variety of organ systems, rather than requiring separate indications for these various disease manifestations. The precedent of approval of agents by organism, rather than disease state, has been established, and is adaptable to evaluation of antibacterial agents.

Several critical issues should be addressed by sponsors if an indication is sought for treatment of specific bacterial organisms across multiple diseases.

Types of Diseases to Be Enrolled Should Be Justified

If the clinical trial is designed to be analyzed using a traditional approach in which data are combined or collapsed across different disease states (as opposed to an approach using hierarchical modeling, as discussed further in the Bayesian Analysis section), it is not advisable to include disease states with significant variations in severity (eg, combining urinary tract infections with life-threatening infections, such as bloodstream infection, in the same study). Such mixing of nonfatal and fatal infections for noninferiority studies is never done, as the efficacy of the experimental drug for the nonfatal infection could mask inferiority in the more severe infections. In contrast, including less severe infections in superiority studies may mask true superiority of the experimental agent for the more severe infections.

As discussed below, Bayesian hierarchical models are useful for a rigorous and coherent analysis of data that arise from subjects with multiple infectious diseases syndromes of varying severity. Such a modeling approach can serve as an alternative means to design and analyze an organism-specific study (discussed further in the Bayesian Analysis section). Sponsors should justify each disease manifestation included in the planned study if the resulting data are to be combined across diseases. Justification should focus on ensuring that the diseases selected are sufficiently similar for pooling based on similar natural history and morbidity and mortality rates. When selecting diseases for a study using traditional inferential statistical methods, sponsors should carefully consider the risk that inclusion of less severe diseases could reduce the power of the study (for a given sample size) to detect true superiority of the experimental agent for more severe diseases. In general, clinical infectious diseases syndromes of sufficient severity to have their data combined in an organism-specific study include bloodstream infection, endocarditis, meningitis or other central nervous system infections, severe intra-abdominal infections, necrotizing soft tissue infections, nosocomial pneumonia, etc.

In addition, any infection, irrespective of the originating site (eg, UTI), could be sufficiently severe to include if disease severity criteria are used to enrich for severely infected patients. Specifically, when enrolling a trial with multiple diseases, validated disease severity scoring systems (eg, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation [APACHE], sequential organ failure assessment [SOFA]) can be used as inclusion criteria and/or randomization stratification criteria to ensure that patients with relatively homogenous disease severity undergo balanced randomization across disease subtypes. Stratification by disease type and severity at randomization is important to ensure that the treatment groups are balanced. Likewise, the primary analysis should be stratified, adjusting for disease type and severity, and secondary analyses should be conducted to separately evaluate outcomes by each individual disease included in the study.

Clear and consistent documentation of infection and/or outcomes of antimicrobial therapy is of paramount importance, especially when the number of enrolled patients is relatively small or fully powered statistical analyses are not possible. Adjudication committees have proven useful in such cases, for example, in studies of invasive aspergillosis and S. aureus bloodstream infection [51, 52]. Use of adjudication and/or endpoint assessment committees should be considered for these types of studies.

The Drug Should Be Known to Penetrate Into Relevant Tissues

Enabling data should be available from preclinical and phase 1/2 clinical studies documenting that the investigational and comparator antibacterial agents penetrate into the tissues relevant to all of the infectious disease manifestations included in the planned study [53]. For example, central nervous system infections should not be included in an organism-specific study for which the investigational or comparator antibiotic has poor (or unknown) penetration into cerebral spinal fluid. Similarly, drugs that achieve low plasma concentrations may be inadvisable for study of bloodstream infection.

Infections caused by XDR/PDR bacteria are possible exceptions to this concern. If an infection is only susceptible to one or no available comparator antibiotics, the risk-benefit ratio of study of antibacterial agents with relatively poor target site concentrations may remain favorable. In these cases, sponsors should exercise individual judgment, and provide study specific justification for the risk-benefit ratio of the antibacterial agents selected for study.

The Pharmacokinetics of the Drug Should Be Understood in the Population of Patients to Be Enrolled in the Pivotal Study

Recent experiences with failed phase 3 noninferiority clinical trials of antibacterial agents for treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia underscore the need to understand the pharmacokinetics of antibacterial agents in the ill, target populations studied in the pivotal trials [54]. For example, the pharmacokinetic profiles of ceftobiprole and tigecycline were understood in healthy volunteers. However, critically ill patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia had substantially lower drug concentrations due to hypermetabolism or hyperclearance of the drugs [54, 55]. Therefore, sponsors need specific pharmacokinetic enabling data regarding their drug in patients with the underlying diseases planned for inclusion in an organism-specific pivotal study.

The Drug Should Retain Antibacterial Activity in Relevant Tissues

Recent experience of daptomycin therapy for CAP underscores the need to establish that an antibacterial agent not only penetrates into the target tissues but also retains antibacterial activity in those tissues [56]. Previous to pivotal phase 3 trials for CAP, daptomycin was studied in a hamster model of bacteremic necrotizing pneumonia caused by S. aureus. In that model the drug was known to penetrate into the lung and to be effective [57, 58]. However, that model did not adequately recapitulate the alveolar nature of clinical CAP. Daptomycin failed to meet noninferiority to the comparator regimen in its pivotal clinical trials for CAP [59]. Murine models of alveolar pneumococcal pneumonia were subsequently tested and it was discovered that although daptomycin did penetrate into the lung, the drug was inactivated by pulmonary surfactant and lost much of its antibacterial potency [56]. Thus, sponsors need adequate enabling data demonstrating that the investigational antibacterial agent penetrates and retains antibacterial activity in pertinent tissue organs.

If the above criteria are met, organism-specific studies targeting highly antibiotic resistant bacteria (particularly XDR and PDR bacteria) using traditional analytic methods are a viable option to facilitate enrollment of difficult-to-study infections for which there is a critical public health need for new antibacterial agents.

Sample Size of Clinical Development Programs for Drugs That Meet Critical Public Health Needs

Any clinical development program will have residual uncertainty with respect to the drug's efficacy. That is, there will be some likelihood of rejecting a truly effective drug based on negative studies, and some likelihood of accepting a truly ineffective drug based on positive studies resulting from chance. The degree of acceptable uncertainty consistent with regulatory approval of a new drug depends on the public health need, including the severity of the disease(s) under study and the availability of other agents for treatment of the disease(s). At one extreme, for an untreatable disease with 100% mortality, the survival of even a small number of treated patients would likely constitute evidence of efficacy sufficient to support approval. At another extreme, for a disease that is not fatal and has multiple treatment options, a much more precise estimate of the efficacy and safety of the drug is required to support approval. A similar rationale has been applied to drugs developed under the Orphan Drug Act.

Patients with serious infections caused by XDR/PDR GNB have high mortality rates, are not treatable with effective regimens, and are difficult to identify and consent for enrollment in a clinical trial. Hence, for studies of antibacterial agents for the treatment of XDR/PDR GNB, it is in the interest of public health to allow for flexibility in the sample size, and hence in the precision of the estimate of relative efficacy and safety of the investigational versus active control regimens.

The degree of flexibility in sample size, and hence uncertainty, should be decided on a case-by-case basis. In general, sponsors should justify sample size for such studies by providing a risk-benefit analysis of the investigational therapy versus currently available therapy for the disease(s) being studied. When justifying sample size, the sponsor should consider (1) the specific public health need for new therapy for the disease(s) under study, including the morbidity and mortality of the disease(s) and the limitations of available therapy; (2) the pretrial probability of efficacy, based on robustness and precision of the enabling data, including the preclinical data as well as the quality and relevance of preclinical infectious models, pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic justification, and results of phase 1 and 2 clinical trial results; and (3) the frequency of the disease(s) under study and complexities of subject identification and enrollment. This latter point is important as it is likely that in clinical practice patients without the true intended condition will be exposed to the drug on an empirical basis, resulting in limited incremental benefit but poorly defined risk.

Conduct of one phase 3 superiority clinical trial may suffice to support approval of a new antibacterial agent for the treatment of infections caused by GNB. The number of patients required for the evaluation of safety and efficacy in a clinical development program will vary based upon the severity of the medical need, the strength of the preclinical and previous clinical enabling data, and the robustness of the postapproval plan for additional investigation. In some cases, where strong prior enabling data exist for an investigational agent that may be effective for the treatment of infections caused by XDR/PDR GNB, meaningful efficacy may be demonstrable with very few patients (eg, 20) exposed to investigational therapy and provide a basis for approval. However, approval of any application based on a single trial or a small number of patients is dependent on trial design and execution of the highest quality, and inclusion/exclusion criteria and objective endpoints that ensure robust, clinically relevant conclusions. It is likely that such approval would be accompanied by a requirement for postmarketing surveillance studies.

Bayesian Analysis to Support More Efficient Studies

Bayesian adaptive trial designs for drugs have been discussed in a recent FDA guidance [50]. Potential advantages of the Bayesian paradigm include continuous learning as data accumulate, facilitating frequent interim analyses and enabling earlier termination of the study owing to earlier crossing of futility or success thresholds. As mentioned below, Bayesian hierarchical models allow the coherent integration of efficacy data from multiple disease subgroups, allowing a more precise comparison of a new and standard agent across those diseases. The Bayesian approach also allows relatively straightforward development of adaptive trial designs—designs in which key trial characteristics (eg, the number of active arms, the randomization ratios, the doses administered, the populations enrolled, and the number and timing of interim analyses) are modified during the conduct of the trial in response to data that arise within the trial itself.

Response-adaptive randomization is used to facilitate the efficient testing of multiple study arms (eg, for testing multiple drug doses or multiple combination regimens) by allowing real-time alteration in the randomization schema to increase enrollment in better performing arms. When using response-adaptive randomization, the proportion of new patients randomized to the experimental and control treatments are altered during the course of the trial, in response to the outcomes of the patients previously enrolled and treated. For example, patients can be preferentially randomized to the treatment arm that appears most promising, based on the accumulating data, to improve the outcomes of patients treated with the trial. This is particularly important if the disease in question leads to significant mortality or to long-term morbidity, or if patients are enrolled in the trial under an emergency exception from informed consent.

Response-adaptive randomization can be used to efficiently address other trial goals as well. In a trial that includes a dose-finding objective, patients preferentially may be randomized to doses in areas of the dose-response curve that are particularly relevant. This may lead to substantial improvements in efficiency, especially when the location of the optimal dose is not well known at the beginning of the trial. For example, if the outcomes of patients receiving the experimental treatment are found more variable than the outcomes of patients given the control treatment, randomizing more than half of patients to the experimental treatment will reduce the final uncertainty in the estimated treatment effect.

Another important potential use of Bayesian analytic methods in clinical trials of antibacterial agents is the use of hierarchical models to facilitate organism-specific studies. Bayesian hierarchical models allow information to be flexibly “pooled” across disease subgroups (eg, subgroups defined by the anatomic location of the infection), but doing so only to the degree justified by the consistency in the observed treatment effect across disease subgroups. When sharing of information across subgroups is justified because the observed treatment effect is similar, this method yields greater precision in the estimation of the treatment effect in each subgroup over a traditional analysis in which the data from each disease subgroup are analyzed separately. However, when there is significant heterogeneity in the observed treatment effect, little or no pooling occurs and the results appropriately estimate the heterogeneous treatment effects. This flexibility can be obtained without deciding, a priori, whether the data from distinct disease subgroups will be pooled or not but with prespecification of the criteria that would allow pooling. This reflects the clinically relevant concept that, in a clinical syndrome, the overall treatment effect and the effect in each disease subgroup are neither identical nor independent, but correlated.

For organism-specific clinical trials focusing on XDR/PDR GNB, the use of a Bayesian hierarchical modeling approach could yield a coherent and rigorous analysis of outcome data from subjects with multiple diseases with disparate mortality rates. For example, to combine outcomes of various endpoints across disease subgroups in the hierarchical model, the estimate of treatment effect within each disease subgroup is converted to an odds ratio. Then, in the next level of the hierarchy, these estimated odds ratios are assumed to, themselves, be drawn from a distribution or population of treatment effects. Overall estimates of treatment effects, whether evaluating superiority or noninferiority, could then be assessed by examining the “average” value of the odds ratios and uncertainty in this average. The hierarchical model enables a more precise estimate of the overall treatment benefit across multiple subgroups, even if there is heterogeneity in outcomes, or even the treatment effect itself, across the subgroups. For example, consider a study that includes patients with HABP/VABP, bloodstream infection, and meningitis, in which the observed mortality reductions with treatment are from 40% to 25% in patients with HABP/VABP, from 60% to 43% in those with bloodstream infection, and from 80% to 67% for those with meningitis. Even though the baseline mortality rates across the 3 subgroups vary by 2-fold (i.e., from 40% for HABP/VABP up to 80% for meningitis), the resulting odds ratios are all close to 0.5 and a hierarchical model would correctly estimate the overall treatment effect, quantify the variability in treatment effect across subgroups, and yield improved precision and greater power compared to 3 separate analyses. The heterogeneity in absolute declines in death would result in an imprecise overall estimate of treatment benefit using an inferential approach based on pooling. However, a Bayesian hierarchical model would analyze the data by combining odds ratios across subgroups. In contrast, a stratified analysis, for example, based on a Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test, yields a single estimate for the common odds ratio, but is only valid under the strict assumption that the odds ratio is the same across disease subgroups.

Furthermore, a Bayesian hierarchical model enables analysis across subgroups even if different endpoints are used for each subgroup. For example, a trial could enroll patients with HABP/VABP, severe sepsis, and pyelonephritis and a hierarchical model could be built to combine outcomes of mortality for HABP/VABP and severe sepsis and a composite endpoint of clinical improvement and microbiological eradication for pyelonephritis.

Proper Endpoints for Superiority Clinical Trials

Endpoints chosen should be clinically relevant and, if the trial results support superiority, reflect a meaningful clinical advance in how patients feel, function, and survive. Endpoints should be as objective as possible, and attempts should be made to minimize subjective endpoints based on poorly defined “clinical response.”

For life-threatening illnesses, it is strongly advised that a composite primary endpoint include all-cause mortality along with other objective, clinical endpoints. In addition, if mortality is evaluated as part of a composite endpoint (rather than as a sole endpoint), secondary analyses should confirm that there is no evidence of inferiority of the investigational drug for the mortality component of the primary composite endpoint, as it is possible that a mortality difference might be masked by other components in the primary composite endpoint. Furthermore, if a historically controlled superiority clinical trial is conducted, it is likely that mortality will be the only acceptable primary efficacy endpoint. In rare cases, if the disease being studied rarely results in fatality, it is conceivable that a historically controlled study could use another strictly objective (eg, negative culture of a sterile site) endpoint in lieu of mortality.

Depending on the disease being studied, microbiological eradication from the target site may be of extreme importance or may be inadvisable for inclusion in the primary efficacy analysis. For infections of normally sterile body sites (eg, blood, joints, cerebrospinal fluid, urine) that can be accessed without substantial risk to the patient, eradication of bacteria should be included as part of the primary efficacy analysis. For microbiological eradication to be included as an endpoint, samples need to be taken from all patients both prerandomization and at the timepoint of assessment. In contrast, microbiological eradication does not consistently add meaningful information to resolution of clinical infection in patients with infections of the skin, soft tissue, lung, or intra-abdominal cavity unless accompanied by bacteremia.

Selection of Appropriate Comparator Regimens

When conducting a superiority trial of a novel antibacterial agent for the treatment of XDR/PDR GNB infections, it is not necessary—and may be unethical—to limit selection of comparator antibacterial agents to those that are approved by the FDA for the treatment of that organ-specific disease. Rather, emphasis should be on selection of agents and doses that have the highest probability of demonstrating some activity for the treatment of the target organisms in that organ or tissue. As stated earlier, the comparator regimen(s), or the process for choosing it, should be defined a priori in the study protocol, and should not be left up to individual investigators to select at each site. The comparatory regimen should be consistent with contemporary guidelines from authoritative sources if they exist, or there should be justified exceptions.

For trials that enroll patients only after establishing that the infection is caused by an XDR/PDR pathogen, a comparator, or group of comparator agents, has the most favorable predictive activity based on the organism's in vitro susceptibility. The selection of comparator agents for empiric therapy prior to identification of the etiologic organism is more complex. Given that a substantial number of those patients will not be infected with an XDR/PDR organism, it may be necessary to include a second agent that has superior activity against less resistant bacteria. After identification of the etiologic organism (or in the absence of identification of an organism), the regimen used to treat enrolled patients could be narrowed. If the etiologic organism was indeed identified as an XDR or PDR organism, the second agent would be discontinued. In all cases, consideration should be given to geographic variations in approved comparator agents and local epidemiology. Flexibility in comparator selection, and indeed the allowance for multiple comparator agents, may be needed in order to conduct such studies.

Early Initiation of Pediatric Studies

Although it has been traditional for adult phase 3 studies to be completed and fully analyzed prior to testing agents in children for pharmacokinetic or phase 2/3 clinical efficacy and safety, the danger posed by XDR/PDR pathogens for children requires that pediatric studies be undertaken far earlier than has been customary. If such studies are not conducted early in the course of development, once the agent has been approved for the treatment of adults with infections caused by XDR/PDR pathogens, the agent will be used in children when XDR/PDR pathogens are suspected. Substantial numbers of neonates, infants, and children will be treated without knowledge of the proper dosage and basic safety information regarding these newly approved drugs. It has been shown that safety and dosing in children are substantially different for 40% of products [60, 61]. This fraction is much higher in term and preterm infants for both antibiotics [46, 62–65].

Pediatric reform at the FDA and the European Medicines Agency has conclusively shown that while efficacy may be extrapolated in children [60], safety and dosing cannot be extrapolated to younger patients. Inappropriate (inadequate/excessive) drug exposures may not only lead to differences in clinical efficacy compared with adults, but importantly, may result in drug toxicities that can be related to growth and development. Pediatric pharmacokinetic/safety studies should be started at the time that registration trials are begun in adults, and not years later when phase 3 trials are complete.

Children are defined by the Office for Human Research Protections within the US Department of Health and Human Services as a “vulnerable” population. Therefore, in other disease areas, substantial data are usually collected and analyzed in adults prior to starting pediatric clinical trials. However, when studying agents for the treatment of life-threatening infections with limited alternative therapies, the risk-benefit ratio of proceeding cautiously with early initiation of pediatric studies is favorable. The urgency of therapy for XDR/PDR pathogens requires this approach.

Limited Population Antibacterial Drug Approval Pathway

As emphasized above, it will be difficult to randomize large numbers of patients infected by XDR/PDR pathogens during conduct of superiority trials. Furthermore, approval based on studies focused on XDR/PDR pathogens will likely result in a substantially smaller market than traditional approvals based on common infections caused by more susceptible pathogens. The substantial costs of operating a larger superiority trial combined with a small eventual market pose considerable economic challenges. In addition, it is critical that drugs approved based on such studies not be wasted on the treatment of infections for which other antibiotics are already available. Thus, a new regulatory paradigm is needed for antibiotics to treat XDR/PDR pathogens to enable conduct of smaller clinical trials than has traditionally been required. Such a paradigm also must incorporate mechanisms to protect the drugs from overuse and misuse, which will drive resistance to the new agents. IDSA conceived of and continues to promote the establishment of a Limited Population Antibacterial Drug (LPAD) approval pathway to solve these interconnected problems. Under the LPAD mechanism, a drug's safety and effectiveness could be studied in substantially smaller, more rapid, and less expensive clinical trials than traditionally used for antibiotics—much like the Orphan Drug Program permits for other rare diseases. LPAD creates substantial economic advantages, including dramatically less expensive upfront development costs and establishment of market conditions (relatively small market of lethal infections with little to no alternative therapy) that favor pricing premium for approved drugs. Thus, LPAD is a powerful economic incentive for developing drugs of critical public health importance.

Simultaneously, LPAD creates conditions to protect approved drugs from overuse. Specifically, the LPAD mechanism would result in approval only for a very narrow indication (eg, for treatment of a specific XDR/PDR pathogen). Because the safety database of LPAD drugs will be small, such drugs should not be used for treatment of infections for which alternative therapies are available. Because companies may only market drugs based on the approved indication, approval with a narrow indication will help protect the drugs from overuse. Furthermore, medical-legal standards also will help prevent misuse, since it would not be defensible should a serious adverse effect occur in patient treated with an LPAD drug who has an infection treatable by alternative antibiotics with more established safety profiles.

Organized medicine, through the American Medical Association House of Delegates, has officially endorsed LPAD [66]. IDSA supports the creation of the LPAD mechanism through either legislative or regulatory means. Once established, LPAD most certainly will provide FDA with all the assurance it needs to approve antibacterial drugs based upon pathogen-specific clinical trials. In short, LPAD is a win-win—it creates conditions that will encourage development of critically needed new antibiotics, while simultaneously protecting those antibiotics from overuse postapproval.

Notes

Acknowledgments. IDSA's Board of Directors wishes to thank the white paper's drafters, Brad Spellberg, Eric P. Brass, John S. Bradley, Roger J. Lewis, David Shlaes, Paul G. Ambrose, Anita Das, Helen W. Boucher, Yohei Doi, John G. Bartlett, Robert A. Bonomo, Steven P. Larosa, George H. Talbot, Daniel Benjamin, Robert Guidos, Amanda Jezek, and David N. Gilbert, for their tireless efforts to find solutions that address ongoing challenges in the antibacterial research and development pipeline. In particular, the Board wishes to acknowledge the efforts of Brad Spellberg in guiding the development of the white paper. The Board also thanks Dr Karen Bush for her critical review of the white paper.

Author affiliations. David Geffen School of Medicine, and Division of General Internal Medicine, Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor–UCLA Medical Center (Brad Spellberg); Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and Director, Harbor–UCLA Center for Clinical Pharmacology (Eric P. Brass); David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Department of Emergency Medicine, Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor–UCLA Medical Center (Roger J. Lewis); Anti-infectives Consulting, LLC (David Shlaes); Institute for Clinical Pharmacodynamics (Paul G. Ambrose); AxiStat, Inc (Anita Das); Tufts Medical Center and Tufts University School of Medicine (Helen Boucher); Rady Children's Hospital San Diego and University of California, San Diego (John Bradley); Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine (Yohei Doi); Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (John Bartlett); Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Louis A. Stokes VA Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio (Robert A. Bonomo); Beverly Hospital, Beverly, Massachusetts (Steven Larosa); Talbot Advisors LLC, Anna Maria, Florida (George H. Talbot); Duke University School of Medicine (Daniel Benjamin); Infectious Diseases Society of America (Robert J. Guidos, Amanda Jezek); Providence Portland Medical Center, Portland, Oregon (David N. Gilbert).

Potential conflicts of interest. Brad Spellberg—grant and contract support: National Institutes of Health, Cubist, Pfizer, Eisai, The Medicines Company, and Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS); GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Pfizer, Eisai, Meiji, Polymedix, Adenium, Novartis, Anacor, The Medicines Company, and Basilea. Eric P. Brass—Sigma Tau Pharmaceuticals, GSK, Consumer Healthcare Products Association, Kowa Research Institute, Maple Leaf Ventures/Worldwide Clinical Trials, Novo Nordisk, 3D Communications, Catabasis Pharmaceuticals, Allergan, Medtronic, NovaDigm Therapeutics, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Amgen, World Self-Medication Industry, Optimer Pharmaceuticals, Gen-Probe, AtriCure, Talon Therapeutics, Merck, NeurogesX, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, NPS Pharmaceuticals, HeartWare International, Johnson & Johnson (J&J)/McNeil, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals; equity in Calistoga Pharmaceuticals and Catabasis Pharmaceuticals. Roger Lewis—senior medical scientist for Berry Consultants, LLC; consultant to AspenBio Pharma and Roche Diagnostics; chair or member of data and safety monitoring boards (DSMBs) for clinical trials sponsored by multiple institutes of the National Institutes of Health, as well as Octapharma USA and Octapharma AG. David Shlaes—AstraZeneca, GSK, J&J, Sanofi-Aventis, Achillion, Actelion, AtoxBio, Cempra, Furiex, IOTA, Indel, Nabriva, Nosopharm, Polyphor, Tetraphase, Abingworth, Novo, Phase IV, Ventech, and Longitude. Paul Ambrose–research at the Institute for Clinical Pharmacodynamics has been funded by Achaogen, Actelion, Astellas, AstraZeneca, B. Braun Medical, BMS, Cempra, Cerexa, Cubist, Durata, Eli Lilly and Company, Elusys Therapeutics, Ferdora Pharmaceuticals, Forest Research Institute, Furiex Pharmaceutical, GSK, InterMune, ISMED Inc, Janssen Research & Development, Kalidex Pharmaceuticals, The Medicines Company, Meiji Seika Pharma Co, Microbiotix, Nabriva, Nimbus, Pfizer, PTC Therapeutics, Rib-X, Roche, Seachaid Pharmaceutical, Synteract Inc, Tetraphase, and Zogenix. Anita Das—consultant through AxiStat to Achaogen, Cerexa, Cempra, Cubist, Trius, Durata, Nabriva, and Kalidex. Helen Boucher—Basilea, Cerexa, Durata, Merck (adjudication committee), J&J, Rib-X, Targanta/TMC, and Wyeth/Pfizer (DSMB). Yohei Doi—research support to Merck; advisory board of Pfizer. Steven Larosa—consultant fees from Agennix AG and ExThera Medical. George H. Talbot—through Talbot Advisors LLC: board compensation and/or consultancy fees from Actelion, Basilea, Bayer, Cempra, Cerexa, Durata, Cubist-Calixa, FAB Pharma, J&J, Kalidex, Meiji, Merada, Merck, Nabriva, and Wyeth/Pfizer (DSMB); equity interests in Durata, Calixa, Cempra, Cerexa, Kalidex, Mpex, and Nabriva. David N. Gilbert—consultant for Achaogen and Pfizer. Daniel Benjamin—research grants from Astellas, AstraZeneca, and UCB Pharma; consultant for Astellas, Biosynexus, Cubist, J&J, Merck, Pfizer, and The Medicines Company. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Falagas ME, Bliziotis IA. Pandrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria: the dawn of the post-antibiotic era? Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;29:630–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falagas ME, Rafailidis PI, Matthaiou DK, Virtzili S, Nikita D, Michalopoulos A. Pandrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii infections: characteristics and outcome in a series of 28 patients. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;32:450–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valencia R, Arroyo LA, Conde M, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of infection with pan-drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in a tertiary care university hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:257–63. doi: 10.1086/595977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffmann MS, Eber MR, Laxminarayan R. Increasing resistance of Acinetobacter species to imipenem in United States hospitals, 1999–2006. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:196–7. doi: 10.1086/650379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams MD, Nickel GC, Bajaksouzian S, et al. Resistance to colistin in Acinetobacter baumannii associated with mutations in the PmrAB two-component system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3628–34. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00284-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lautenbach E, Synnestvedt M, Weiner MG, et al. Epidemiology and impact of imipenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:1186–92. doi: 10.1086/648450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navon-Venezia S, Leavitt A, Carmeli Y. High tigecycline resistance in multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:772–4. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hjelmevoll SO, Golparian D, Dedi L, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic properties of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates in Norway in 2009: antimicrobial resistance warrants an immediate change in national management guidelines. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:1181–6. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1426-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unemo M, Golparian D, Nicholas R, Ohnishi M, Gallay A, Sednaoui P. High-level cefixime- and ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in France: novel penA mosaic allele in a successful international clone causes treatment failure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1273–80. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05760-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unemo M, Golparian D, Limnios A, et al. In vitro activity of ertapenem vs. ceftriaxone against Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates with highly diverse ceftriaxone MIC values and effects of ceftriaxone resistance determinants—ertapenem for treatment of gonorrhea? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1273–80. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00326-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohnishi M, Golparian D, Shimuta K, et al. Is Neisseria gonorrhoeae initiating a future era of untreatable gonorrhea? Detailed characterization of the first strain with high-level resistance to ceftriaxone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:3538–45. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00325-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spellberg B, Talbot GH for the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP), American Thoracic Society (ATS), and Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) Recommended design features of future clinical trials of anti-bacterial agents for hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia (HABP) and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia (VABP) Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:S150–70. doi: 10.1086/653065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vidal F, Mensa J, Almela M, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia, with special emphasis on the influence of antibiotic treatment. Analysis of 189 episodes. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2121–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carmeli Y, Troillet N, Karchmer AW, Samore MH. Health and economic outcomes of antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1127–32. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.10.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niederman MS. Impact of antibiotic resistance on clinical outcomes and the cost of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(4 suppl):N114–20. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200104001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang CI, Kim SH, Kim HB, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia: risk factors for mortality and influence of delayed receipt of effective antimicrobial therapy on clinical outcome. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:745–51. doi: 10.1086/377200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: Non-inferiority trials. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM202140.pdf. Accessed 28 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powers J. Silver Spring, MD: 2008. Primary and secondary and composite endpoints. Issues in the Design and Conduct of Clinical Trials of Antibacterial Drugs in the Treatment of Community-Acquired Pneumonia: a workshop co-sponsored by the IDSA and FDA. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lubsen J, Kirwan BA. Combined endpoints: can we use them? Stat Med. 2002;21:2959–70. doi: 10.1002/sim.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wunderink RG, Niederman MS, Kollef MH, et al. Linezolid in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia: a randomized, controlled study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:621–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gordon NC, Wareham DW. A review of clinical and microbiological outcomes following treatment of infections involving multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii with tigecycline. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:775–80. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karageorgopoulos DE, Kelesidis T, Kelesidis I, Falagas ME. Tigecycline for the treatment of multidrug-resistant (including carbapenem-resistant) Acinetobacter infections: a review of the scientific evidence. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:45–55. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]