Abstract

Focal brain ischemia in adult rats rapidly and robustly induces neurogenesis in the subventricular zone (SVZ) but there are few and inconsistent reports in mice, presenting a hurdle to genetically investigate the endogenous neurogenic regulators such as ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF). Here, we first provide a platform for further studies by showing that middle cerebral artery occlusion in adult male C57BL/6 mice robustly enhances neurogenesis in the SVZ only under very specific conditions, i.e., 14 days after a 30 min occlusion. CNTF expression paralleled changes in the number of proliferated, BrdU-positive, SVZ cells. Stroke-induced proliferation was absent in CNTF−/− mice, suggesting that it is mediated by CNTF. MCAO-increased CNTF appears to act on C cell proliferation and by inducing FGF2 expression but not via EGF expression or Notch1 signaling of neural stem cells in the SVZ. CNTF is unique, as expression of other gp130 ligands, IL-6 and LIF, did not predict SVZ proliferation or showed no or only small compensatory increases in CNTF−/− mice. Expression of tumor necrosis factor-α, which can inhibit neurogenesis, and the presence of leukocytes in the SVZ were inversely correlated with neurogenesis, but pro-inflammatory cytokines did not affect CNTF expression in cultured astrocytes. These results suggest that slowly up-regulated CNTF in the SVZ mediates stroke-induced neurogenesis and is counteracted by inflammation. Further pharmacological stimulation of endogenous CNTF might be a good therapeutic strategy for cell replacement after stroke as CNTF regulates normal patterns of neurogenesis and is expressed almost exclusively in the nervous system.

Keywords: Ciliary neurotrophic factor, FGF2, Ischemia, Mouse, Middle cerebral artery occlusion, Neurogenesis, Notch1, Progenitor, Stroke, Subventricular zone

Introduction

It is well-known that focal cerebral and striatal ischemia enhances neurogenesis in the SVZ and subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus (Burns et al., 2009; Kernie and Parent, 2010; Zhang and Chopp, 2009). Many studies have shown that ischemic injury induced by MCAO in adult rats increases the number of proliferating SVZ cells (Arvidsson et al., 2002; Jin et al., 2001; Parent et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2001). Stroke-induced neurogenesis also seems to occur in the human brain (Jin et al., 2006; Macas et al., 2006). These results have raised the possibility that new neurons formed by endogenous neural stem cells can be used to replace cells as a treatment for stroke. A better understanding of the molecular regulators of stroke-induced neurogenesis and identification of endogenous drug targets to promote neurogenesis would be facilitated by the use of transgenic and knockout mice. However, in contrast to rats, it is not clear under which conditions stroke induced by MCAO in mice enhances SVZ neurogenesis. Only a few papers have reported changes in the SVZ of mice with one showing decreases at 3 days after MCAO and a return to baseline at 7 days (Tsai et al., 2006) and another an approximately 50% increase at 14 days after a permanent cortically restricted stroke (Wang et al., 2007). Some of the reasons for these apparent discrepancies and the differences between rats and mice might include mouse-specific requirements for the occlusion and post-injury times, or technical issues in the much smaller mouse.

Injured cells release many cytokines and growth factors after ischemia, which may be responsible for the neurogenic responses to stroke. Treatment with exogenous growth factors such as FGF2, EGF, BDNF, VEGF, EPO, CNTF and IGF-1 have been shown to promote ischemia-induced neurogenesis, predominantly in rats (Chmielnicki et al., 2004; Esneault et al., 2008; Jin et al., 2004; Schabitz et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2003; Tureyen et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2007; Yan et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2008). Of these, IGF-1 (Yan et al., 2006) and CNTF have been confirmed to regulate a proportion of endogenous neurogenesis under normal conditions using knockout mice or antibodies (Yang et al., 2008). However, only IGF-1 has been shown, by antibody knock-down, to be involved in the response after stroke (Yan et al., 2006), reiterating the need for using more genetic mouse models. CNTF is of particular interest as it is up-regulated in the ischemic cortex nearly 20 fold by 2 weeks after stroke (Lin et al., 1998), enhances normal adult SVZ neurogenesis in mice and can be increased through systemic D2 dopamine agonist injections (Emsley and Hagg, 2003; Yang et al., 2008). Thus, CNTF might be a good therapeutic target for stroke but its role in stroke-induced neurogenesis remains to be investigated. Some of the cytokines produced during the inflammatory response after stroke, such as IL-6, TNFα, and IFNγ, have anti-proliferative effects in the SVZ and hippocampal subgranular zone (Ben-Hur et al., 2003; Iosif et al., 2006, 2008; Monje et al., 2003; Vallieres et al., 2002). The interactions between pro- and anti-neurogenic cytokines remain to be investigated and would be facilitated by using genetically altered mice.

The present study was aimed at investigating under which conditions reproducible MCAO in mice would enhance SVZ neurogenesis, providing a platform to determine whether and how endogenous CNTF regulates this stroke-induced neurogenesis.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

A total of 176 male C57BL/6 (12 weeks of age; 24–30 g; stock# 000664, The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and 80 female and male CNTF knockout mice (VG#199 in (Valenzuela et al., 2003)) and their heterozygous and wildtype littermates were used. The latter were age- and gender-matched to provide equal representation in each experimental group. Genotyping of tail snips was performed with the Velocigene genotyping protocol provided by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals who produced the mice. These mice were originally on a mixed C57BL/6 × 129Sv background and have been backcrossed into C57BL/6 for 5 times since we received them. All procedures and animal care were carried out according to the protocols and guidelines of the University of Louisville Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the National Institutes of Health.

Care and use of experimental animals

Deep anesthesia for all invasive procedures was achieved by an intraperitoneal injection of Avertin (0.4 mg 2,2,2-tribromoethanol in 0.02 ml of 1.25% 2-methyl-2-butanolin saline per gram body weight; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Post-surgical care included injection of 1.5 μg buprenorphine in 0.1 ml saline (1:20 dilution of 0.3 mg/ml stock solution; Ben Venue Laboratories, OH) subcutaneously once the mice recovered from anesthesia to prevent fatal interaction with Avertin, followed by injections every 12 h for a total of 4 injections. Gentamicin (20 μg in 100 μl saline; 1:200 dilution of a 40 mg/ml stock solution; ButlerSchein, Dublin, OH) was injected subcutaneously during surgery, as well as 2 and 4 days post-surgery.

Over the course of developing the consistent MCAO in mice and the effects on SVZ neurogenesis we used different occlusion times, including 15, 30 or 45 min. The neurological deficits caused by the 30 and 45 min MCAO required special and intensive care of the mice. Thus, mice were weighed daily and any lost weight was replaced by a subcutaneous injection of an equal amount of Ringer’s lactate–dextrose solution. They also were provided with a hydration gel-pack and peanut butter cookies placed on the bedding, in addition to their regular water bottle and chow.

Reproducible mouse MCAO model of focal ischemia

Focal cerebral and striatal ischemia was induced by MCAO for various occlusion times followed by reperfusion. After the mice were anesthetized, a needle probe of a Laser-Doppler Flowmetry device (Moor VMS-LDF, VP10M200ST, P10d, Moor Instruments Ltd., Wilmington, DE) was glued onto the superior portion of the temporal bone to monitor cerebral blood flow. After a midline skin incision in the neck area, with the mouse in the supine position, the left external carotid artery (ECA) was exposed and isolated from its small artery branches with a bipolar coagulator (N.S. 237, Codman & Shurtleff, Inc., Randolph, MA). The ECA was ligated with 5–0 silk suture approximately 3 mm distal to its origin. Microvascular clips were temporarily placed on the common carotid artery and the internal carotid artery, and then an arteriotomy was made in the ECA. Next, a filament was inserted into the ECA and advanced over 8–9 mm to the carotid bifurcation along the internal carotid artery and to the origin of the middle cerebral artery (MCA). We tested different types of filaments (Supplemental results) and the results in the main text were with the most reliable 0.21 mm diameter DOCCOL filaments (6021PK5Re, DOCCOL Co, Redlands, CA). Cerebral blood flow decreases immediately after a successful MCAO to about 20% of baseline and was used to confirm the correct placement of the filament. After 15, 30 or 45 min the filament was removed to restore blood flow of the MCA territory, which includes the striatum and overlying cortex, and the microvascular clips were removed. Sham-operated mice received the same surgery except for the insertion of the filament. Core body temperature was maintained at 37.0±0.5 °C with a heating pad during the operation and the recovery period. The wound was closed in layers using silk and metal sutures.

Immunocytochemistry

BrdU (50 mg/kg per injection; Sigma B5002) was injected intraperitoneally twice a day during the 3 days before perfusion. Sixteen hours after the last BrdU injection, the mice were perfused transcardially with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4) and 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer (PB, 0.1 M, pH 7.4). Afterwards, the brains were fixed overnight in paraformaldehyde and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in PB for 24 h. Coronal 30 μm thick sections through the brains were cut on a sliding freezing microtome (Leica SM 2000R, Bannockburn, IL). Starting at a random point along the rostrocaudal axis of the brain, every sixth section through the SVZ was immunostained for BrdU (MAB3510, mouse IgG, clone BU-1, 1:30,000; Millipore, Billerica, MA). Briefly, sections were incubated in 50% formamide in 2× SSC at 65 °C for 2 h, rinsed in fresh 2× SSC, incubated in 2 N HCl at 37 °C for 30 min, and neutralized in 0.1 M boric acid, pH 8.5, for 10 min. This was followed by incubation in 5% normal horse serum for 1 h to block non-specific staining, in primary antibodies overnight, biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG (1:800; BA2001, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 h, all dissolved in PBS containing 5% horse serum. This was followed by an incubation in avidin–biotin complex conjugated with peroxidase for 1 h (1:600 in PBS, PK6100, Vector Laboratories). Chromogen reaction was performed with 0.04% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (D5637, Sigma) solution containing 0.06% nickel ammonium sulfate and 1% hydrogen peroxide in 0.05 M Tris buffer–HCl (TBS). Sections were then rinsed in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, mounted on glass slides, and coverslipped with Permount (SP15, Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ). To detect neuroblasts, three sections throughout the SVZ were stained for double-fluorescence with BrdU and their marker doublecortin (dcx). Therefore, sections were incubated in 2 N HCl for 1 h at room temperature, neutralized in 0.1 M boric acid, pH 8.5, for 10 min, and followed by washing overnight in 0.1 M TBS at 4 °C. Sections were incubated with 5% donkey serum in TBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature followed by an overnight incubation at 4 °C in TBS containing 5% donkey serum, goat anti-DCX (1:500, SC8066, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and mouse anti-BrdU (1:5000, MAB3510, Millipore, Billerica, MA). They were incubated in TBS containing 5% donkey serum, 0.3% Triton X-100, fluorescent donkey anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies (1:500, Alexa Fluor 594, A21203, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and donkey anti-goat IgG secondary antibodies (1:500, Alexa Fluor 488, A11055, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were washed and then coverslipped with antifade Gel/Mount aqueous mounting media (Southernbiotech, Birmingham, AL). In between steps, the sections were washed 3 times for 10 min in TBS.

For CD45 staining, sections were incubated with 5% donkey serum in PBS (to block non-specific staining) containing 0.3% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature followed by an overnight incubation at 4 °C in PBS containing 5% donkey serum and rat anti-CD45 (1:500, CBL1326, Millipore, Billerica, MA). Next, sections were incubated in PBS containing 5% donkey serum and fluorescent donkey anti-rat IgG secondary antibodies (1:200, Alexa Fluor 594, A21209, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 h at room temperature, and coverslipped with antifade Gel/Mount aqueous mounting media (Southernbiotech, Birmingham, AL). In between steps, the sections were washed 3 times for 10 min in PBS.

Unbiased stereological counting and statistical analysis

The number of BrdU-positive nuclei in the SVZ was counted in all mice by the same person who was blinded to the treatment using an unbiased optical fractionator stereological method (Stereologer; Systems Planning and Analysis, Alexandria, VA) (Baker et al., 2004) and a motorized Leica DMIRE2 microscope. The reference space was defined as a 50-μm-wide strip of the entire lateral wall of the lateral ventricle ipsilateral to the MCAO or sham operation and rostrocaudally from the genu of the corpus callosum to the caudal end of the decussation of the anterior commissure. Frame size was 2000 μm2 and frame spacing was 75 μm. BrdU-positive nuclei were counted in software-defined frames placed within the reference space. The total number of BrdU-positive nuclei was calculated by the software as: n=number of nuclei counted×1/section sampling fraction×1/area sampling fraction×1/thickness sampling fraction. In addition, the number of events in each section was derived from the data files to determine whether there might be rostrocaudal differences in the responses to the MCAO. The number of neuroblasts was counted using a 20× objective by identifying dcx-positive cells with BrdU-labeled nuclei in the most populace dorsolateral part of the SVZ and compared to the total number of BrdU-labeled nuclei in the same counting area. Statistical analyses were performed with Student’s t test with a value of p<0.05 considered as statistically significant.

Real time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qPCR)

After 5 or 12 days, i.e., during the time when BrdU was injected in other groups, mice were processed to measure CNTF expression in the SVZ. The brains were collected fresh and cut in the coronal plane into 1 mm slices using single sided razor blades and 0.5 mm wide SVZ strips freshly dissected from between the genu and the anterior commissure decussation. Total RNA was isolated using a commercial kit (74104, Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and was used as templates in reverse transcription (RT), which runs with 1.0 μl total RNA (1.0 μg), 1.0 μl of 500 ng/μl random primers (C118A, Promega, San Luis Obispo, CA), 1.25 μl of 10 mM dNTPmix (U151A, Promega), 5 μl 5× RT buffer, 1.75 μl RNase-free water, and 1 μl of 200 U/μl MMLV-RT(M170A, Promega). RT reactions were performed at 70 °C for 5 min and 37 °C for 1 h. QPCR was performed using specific primer sets (CNTF: mM0046373_m1 FAM, Ki67: mM01278608_m1 FAM, PCNA: Mm00448100_g1 FAM, Sox2: Mm03053810_s1 FAM, Musashi1: Mm0045224_m1 FAM, EGFR: Mm00433023_m1 FAM, TNFα: mM00443258 m1 FAM, LIF: mM00434762_g1 FAM, IL6: mM00446190_m1 FAM, EGF: Mm00438696_m1 FAM, FGF2: Mm00433287_m1 FAM, Notch1: Mm00435245_m1 FAM, Mash1 (Ascl1): Mm03058063_m1 FAM, Delta3 (Dll3): Mm00432854_m1 FAM, Hes1: Mm00468601_m1 FAM, Hes5: Mm00439311_g1 FAM, and GAPDH: 4352339E VIC, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). RT reactions were performed at 37 °C for 1 h. PCR reactions were performed using the TaqMan® Gene Expression Master Mix kits (4369016, Applied Biosystems) as follows: 10 min at 95° followed by 40 cycles of 95° for 15 s, 60° for 1 min in an ABI 7900 Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems). After qPCR, the numbers of cycles for the gene (e.g., CNTF) fragment were subtracted from (normalized to) that for the GAPDH fragment to calculate the relative abundance of the specific mRNA. We used the 2−ΔΔCt method to calculate changes compared to sham-operated mice.

Results

Only 30 min MCAO causes robust increases in SVZ proliferation in adult mice

We first determined that commercially available intraluminal DOCCOL filaments provided reliable injuries in C57BL/6 mice compared to the unreliable results with often-used heat expanded sutures (Supplemental results). We had next tested the potential effects of endogenous CNTF on neurogenesis induced by a 15 min MCAO with the DOCCOL sutures, but surprisingly detected no increase in wildtype, CNTF+/−, or CNTF−/− littermates at 7 days (Supplemental results). In view of the negative data, we increased the occlusion time and post-injury time using standard male C57BL/6 mice. The 30 min occlusion caused damage in a large part of the neighboring striatum, but no infarct of the SVZ unlike the 45 min occlusion (Fig. 1). Sections stained for BrdU 14 days post-injury showed a lack of an overt neurogenic response compared to sham-operated mice (Fig. 2a) after the 15 (Fig. 2b) and 45 min MCAO (Fig. 2d) but a robust response after the 30 min MCAO (Fig. 2c). The number of SVZ BrdU+ nuclei was not significantly affected by the 15 min MCAO at 7 days (MCAO: 30,298±1,521 versus sham: 30,747±2,310; Fig. 3a) but had increased by 19% at 14 days post-injury (MCAO: 34,585±1,535 versus sham: 29,094±2,912, pb0.05). After a 30 min MCAO, the number of BrdU+ nuclei in the SVZ increased by 23±0.6% over sham at 7 days (p<0.05) and increased close to 2-fold at 14 days post-injury (95±2% over sham; p<0.01). After a 45 min MCAO, the number of BrdU+ nuclei in the SVZ was unchanged at 7 days post-injury (97±11% of sham; p=0.41). Combined with the finding of ischemic lesions affecting the SVZ after the 45 min MCAO, this suggests that injury to the SVZ reduces its responsiveness. Due to high mortality, we were unable to obtain results 14 days after a 45 min MCAO. The results so far show that MCAO induces robust proliferation in the SVZ of adult mice only with a consistent filament size and under very specific conditions.

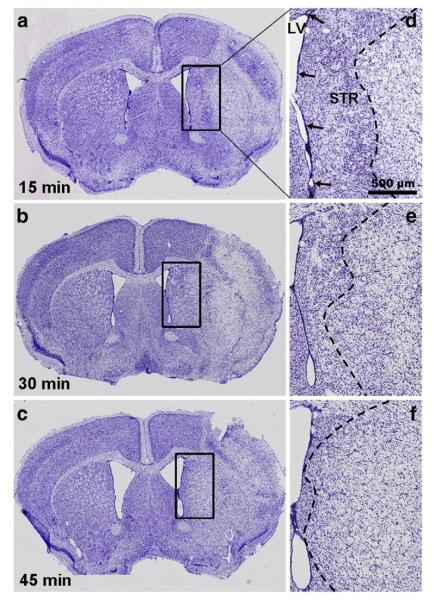

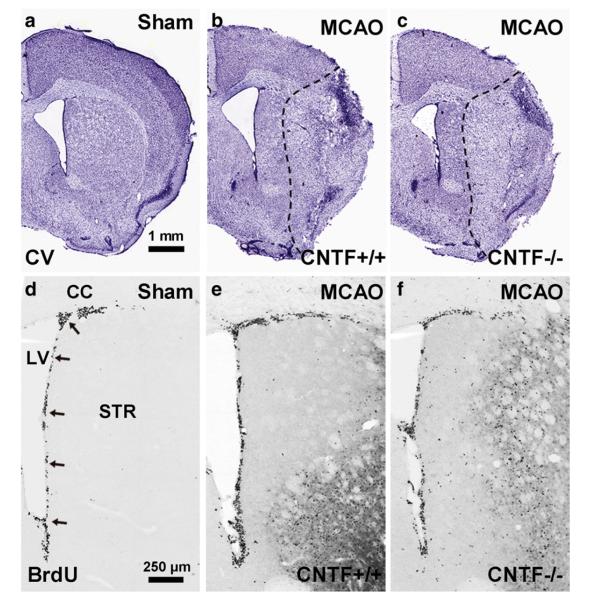

Fig. 1.

MCAO injury in adult mice close to the SVZ is dependent on occlusion time. Injury at 7 days after MCAO in C57BL/6 mice can be seen by the loss of neurons in cresyl violet stained sections. (a) The 15 min occlusion induced neuronal loss mainly in the striatum (STR), (b) the 30 min occlusion caused damage in most of the overlying cerebral cortex as well, whereas (c) the 45 min occlusion caused extensive damage including most of the striatum and large parts of the cerebral cortex. The SVZ (arrows) located between the lateral ventricle (LV) and the striatum is not reached by the ischemic injury (border indicated by a stippled line) after (d) 15 min or (e) 30 min MCAO, whereas (f) a 45 min occlusion induced ischemic damage to the SVZ. Scale bar, 500 μm.

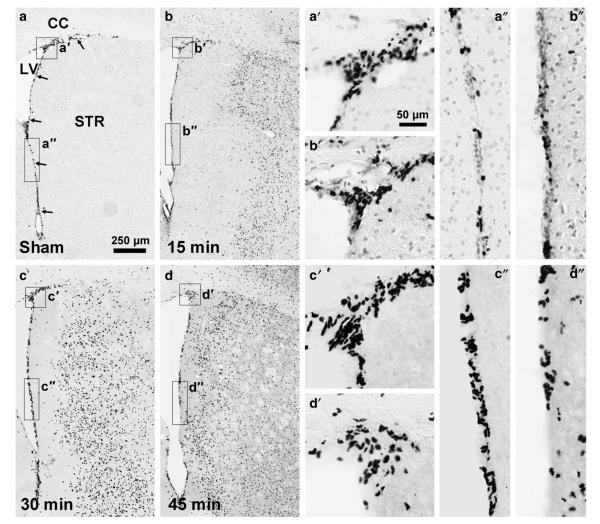

Fig. 2.

Only a 30 min MCAO overtly increases proliferation in the SVZ. Proliferating cells were labeled by injection of BrdU during the 3 days before analysis at 14 days after MCAO in C57BL/6 mice. As shown in coronal sections through the SVZ (arrows) and striatum (STR), the number of BrdU+SVZ nuclei appeared to be increased after a 30 min occlusion (c), compared to sham-treated mice (a). The 15 min (b) and 45 min occlusion times did not seem to affect the number of proliferated SVZ cells (d). Note the clear anatomical separation between the BrdU+inflammatory cells in the striatum and the progenitors in the SVZ. BrdU+SVZ nuclei were also readily identifiable by their much smaller size. Scale bar 250 μm. CC=corpus callosum, LV=lateral ventricle. The three columns on the right show higher magnification images of the boxed areas in (a–d) and are indicated for example as a’ or a” for the dorsal and vertical parts of the SVZ, respectively. Scale bar=50 μm. The images were taken from animals whose stereological counts were close to the group average.

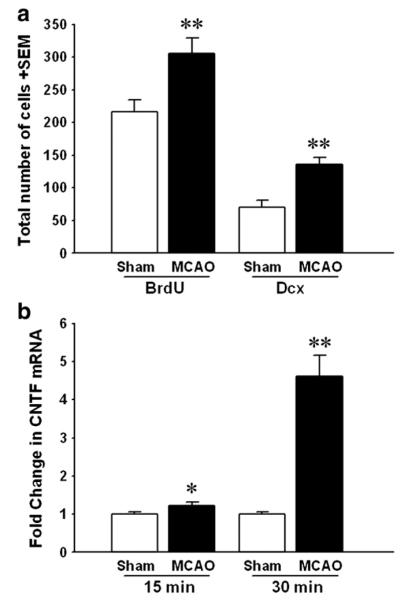

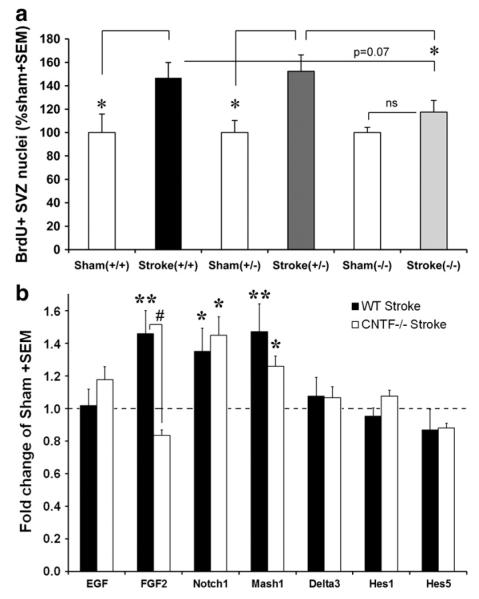

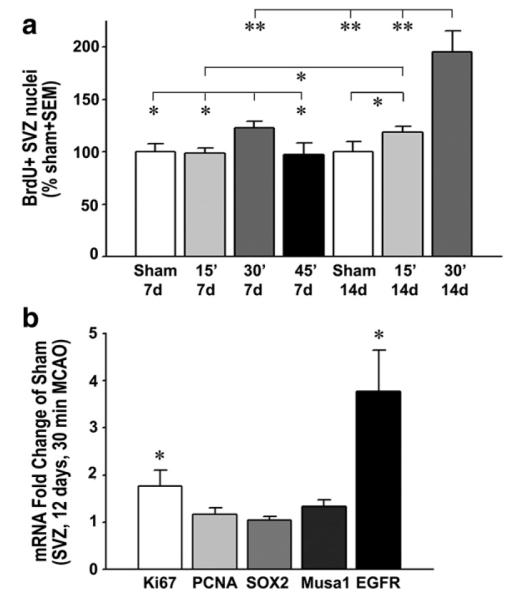

Fig. 3.

A 30 min MCAO induces a robust increase in proliferation in the SVZ after 14 days. (a) The number of BrdU+ SVZ nuclei counted by unbiased stereology in C57BL/6 mice was not significantly changed by a 15 min MCAO (light gray columns) compared to that of sham group (white columns) at 7 days and had increased by only 19% at 14 days post-injury. After a 30 min MCAO (gray columns), the increase was 23% and 95%, respectively. The number of BrdU+ SVZ nuclei was not changed by a 45 min MCAO (black column). Sham 7 days, n=5; 15 min MCAO 7 days, n=3; 30 min MCAO 7 days, n=9; 45 min MCAO 7 days, n=5; sham 14 days, n=4; 15 min MCAO 14 days, n=8; 30 min MCAO 14 days, n=6. *p<0.05,**p<0.01. (b) qPCR measurements of the SVZ 12 days (in the middle of the BrdU injections of the other experiments) following a 30 min MCAO shows increases, compared to sham, in the mRNA for the proliferation marker Ki67, but not PCNA, no effect on the neural stem cell marker Sox2, but an increase in musashi1 (musa1) and EGFR, both present in progenitor C cells; n=5 each. *p<0.05.

Stroke increases C cell proliferation in the SVZ

To obtain a better insight into the type of proliferating SVZ cells, we used qPCR on the SVZ tissue of a new set of mice 12 days following a 30 min MCAO. This time point was chosen to be within the time when BrdU had been injected in the previous experimental mouse groups. Expression of the proliferation marker Ki67 (Wojtowicz and Kee, 2006) was significantly increased by 77% compared to sham values (Fig. 3b), consistent with the increase in BrdU (Fig. 3a). Within the same tissue, PCNA, which has been used to detect proliferating SVZ cells by immunocytochemistry, was not significantly changed (Fig. 3b; p=0.366). This might be caused by low levels of PCNA expression in every cell, including the more numerous striatal cells included in the dissected tissue. The stroke-induced proliferation did not appear to be mediated by increased self-renewal of neural stem cells (NSCs) as expression of their marker Sox2 (Ellis et al., 2004) was not increased (Fig. 3b; p=0.662). Musashi-1, a marker for SVZ stem and progenitor cells (Kaneko et al., 2000), was increased by 33% (Fig. 3b). Most of the proliferation was likely due to the transient amplifying C cell progenitor population as their marker EGFR (Doetsch et al., 2002) was increased close to 4-fold (Fig. 3b).

Stroke increases neurogenesis in the SVZ

Under normal conditions the C cells predominantly produce neuroblasts. We determined whether the stroke-induced proliferation also resulted in more neuroblasts or not, using 14 day 30 min MCAO mice which had shown an increase in SVZ proliferation. Confocal z-stack images of the most populace dorsolateral region of the SVZ showed a clear stroke-induced increase in dcx staining (Fig. 4b) as compared to sham-operated mice (Fig. 4a). The total number of BrdU nuclei also appeared to be increased. Counts of the number of BrdU+ nuclei and the total number of dcx/BrdU+ neuroblasts showed that both were increased after stoke (by 42 and 93%, respectively, compared to sham, p<0.01, p<0.005; Fig. 5a). Interestingly, the number of additional neuroblasts (dcx) was not significantly different from the number of additional BrdU+ nuclei following stroke (65±11 vs. 90±23; p=0.14 paired t test). This suggests that most of the SVZ C cells that proliferated in response to the stroke produced neuroblasts.

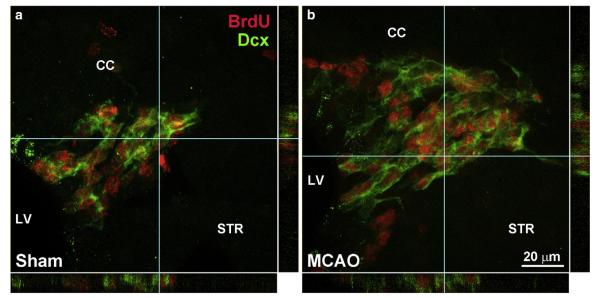

Fig. 4.

Stroke increases SVZ neurogenesis. Confocal images of the dorsolateral SVZ show numerous BrdU+ nuclei of proliferated cells (red), including the BrdU+ neuroblasts as identified with dcx staining (green). The volume-rendered images are from 9 μm thick z-stacks. Sham-operated mice (a) clearly have fewer BrdU+ nuclei and dcx+ cells than those with a 30 min MCAO at 14 days post-injury (b). Images were taken from mice and sections that are representative for the group averages (Fig. 5a). CC=corpus callosum, LV=lateral ventricle, STR=striatum. Scale bar=20 μm.

Fig. 5.

Stroke-induced neurogenesis is accompanied by increases in CNTF. (a) The number of BrdU+ nuclei (left columns) and dcx-stained neuroblasts (right columns) was clearly increased at 14 days following an MCAO as compared to sham-operate mice. Note that the number of additional dcx cells is of the same magnitude as the additional BrdU+ nuclei, suggesting that stroke-induced proliferation produces predominantly new neuroblasts in the SVZ. n=4 each. **p<0.01. (b) The levels of CNTF mRNA in the SVZ of a separate set of C57BL/6 mice were increased by 23% at 12 days after 15 min MCAO and approximately 5-fold after a 30 min MCAO compared to those of sham-operated mice. Sham 15 min, n=6; 15 min MCAO, n=6; sham 30 min, n=9; 30 min MCAO, n=6. *p<0.05,**p<0.01.

Stroke increases CNTF expression in the SVZ

Our objective in this study was to determine the contribution of endogenous CNTF to stroke-induced neurogenesis. The differences in the neurogenic responses seen after 15 vs. 30 min at 14 day post-MCAO times provided an opportunity to correlate them with CNTF expression levels. In C57BL/6 mice with a 15 min MCAO, CNTF expression in the SVZ was increased by 23% at 12 days (1.23±0.08 fold versus sham: 1.00±0.06; n=6 each, p<0.05; Fig. 5b), consistent with the small increase in proliferation (Fig. 3a). After the 30 min MCAO, when a clear increase in neurogenesis was observed (Figs. 3a and 5a), CNTF expression was increased by more than 4-fold at 12 days post-injury (4.62±0.54, versus sham: 1.00±0.05, n=6 and 9, p<0.000001). These data suggests that CNTF could mediate or be involved in stroke-induced neurogenesis.

Lack of CNTF greatly reduces the stroke-induced neurogenic response

To confirm the role of CNTF in stroke-induced neurogenesis, CNTF−/− mice were injured by a 30 min MCAO and compared to their littermates. All genotypes showed a similar extent of injury (Fig. 6b and c). The control littermates showed an apparent increase in SVZ proliferation as shown by BrdU incorporation, whereas the CNTF−/− mice seemed to lack this response (Fig. 6e and f compared to sham, Fig. 6d). The number of BrdU+ SVZ cells in wildtype CNTF mice was significantly increased by about 47±13% compared to that of sham-operated mice (+/+ MCAO: 37,140±3,312 versus +/+ sham: 25,297±4,021; p<0.05; Fig. 7a). The number of BrdU+ SVZ nuclei in CNTF +/− was increased by 52±14% (p<0.05) but CNTF−/− mice showed no significant increase (18±10%, p=0.185) after MCAO compared to the sham values of the individual genotypes. The BrdU values for the heterozygous mice were significantly greater than that of the CNTF−/− mice (p<0.05; Fig. 7a). There were no significant differences between genders in any of the genotypes in either sham-operated or MCAO mice (data not shown). The response to MCAO by the CNTF−/− mice was less than 30–40% (although not significant compared to sham) of that seen in their littermates, suggesting that 60–70% or more of the increased SVZ neurogenesis is mediated by CNTF.

Fig. 6.

CNTF mediates stroke-increased neurogenesis: histology. The extent of ischemic damage 14 days after a 30 min MCAO was similar in CNTF+/+ wildtype (b) and CNTF−/− (c) littermate mice as shown in cresyl violet stained coronal sections of the brain. Scale bar in (a) is 1 mm for (a–c). Compared to sham-operated wildtype littermates (d), those with a 30 min MCAO (e) showed an apparent increase in proliferation in the SVZ (arrows) as shown by BrdU incorporation. The CNTF−/− mice seemed to lack this response (f). Scale bar in (d) is 250 μm for (d–f). CC=corpus callosum, LV=lateral ventricle.

Fig. 7.

CNTF mediates stroke-increased neurogenesis: BrdU quantification. (a) The number of SVZ BrdU+ cells as quantified by unbiased stereology in wildtype (+/+) and heterozygous (+/−) littermate mice was significantly increased by about 47% and 52%, respectively, at 14 days after a 30 min MCAO compared to that of their sham groups. In contrast, CNTF−/− mice showed no significant increase (18±10%) compared to their shams and the BrdU value was significantly lower than that of the heterozygous mice. Sham+/+, n=4; MCAO+/+, n=8; sham+/−, n=4; MCAO+/−, n=5; sham−/−, n=4, MCAO−/−, n=5. *p<0.05. (b) At 12 days following a 30 min MCAO, mRNA expression levels of EGF, FGF2 and Notch1 pathway molecules were measured in the SVZ by qPCR and expressed as a fold change compared to sham-operated mice of the same genotype. Note the differential expression in FGF2 following MCAO between the wildtype (WT) and CNTF−/− mice, and the increased expression of Notch1 and Mash1 in both. For this experiment only, we combined C57BL/6 mice with CNTF+/+ mice (their values were not different) into a WT group due to insufficient RNA remaining for some of the mice. WT sham n=8, WT MCAO n=6; CNTF−/− sham 4, CNTF−/− MCAO n=3. *p<0.05,**p<0.01 compared to sham. #p<0.05 between WT and CNTF−/−.

Like CNTF, LIF and IL-6 activate the gp130 receptor, which is involved in stimulating NSC renewal in the adult SVZ (Chojnacki et al., 2003). Others have found that LIF can compensate for the lack of CNTF in null mice in the eye (Kirsch et al., 2010). Our data comparing CNTF−/− and littermates show that LIF and IL-6 do not compensate under sham-operated (normal) conditions (Supplemental results). At 12 days following a 30 min MCAO, the CNTF−/− mice had a 40–50% larger increase in LIF than their control littermates, which is much less than the 5–11 fold increase in CNTF seen in the same littermates (Supplemental Fig. 1). This suggests that compensation by LIF, if it occurs, is small. IL-6 values were not significantly different between CNTF−/− and CNTF+/+ or CNTF+/− littermates.

MCAO-increased CNTF induces FGF2 expression in the SVZ

To find potential proliferation-inducing mechanisms in the SVZ downstream of CNTF following stroke, we measured the expression levels of EGF, FGF2, and the Notch1 pathway, all major contributors to SVZ neurogenesis (Chojnacki et al., 2003; Kuhn et al., 1997; Zheng et al., 2004). Under sham conditions, EGF mRNA expression levels in the SVZ as measured by the deltaCT values were only approximately 10% of those of FGF2 (data not shown). FGF2, but not EGF, expression increased significantly at 12 days after a 30 min MCAO in wildtype mice (Fig. 7b). This increase in FGF2 was not seen in CNTF−/− mice (Fig. 7b), suggesting that the MCAO-induced CNTF causes the increase in FGF2 expression in wildtype mice. Notch1 expression was increased by the MCAO in both genotypes (Fig. 7b), suggesting that CNTF does not regulate Notch1 expression under these conditions. MCAO-increased Mash1 expression was also not significantly different between the CNTF−/− and wildtype SVZ (Fig. 7b). The Notch1 ligand, Delta3, which is downstream of Mash1 (Chojnacki et al., 2003), was not significantly affected by the MCAO in either genotype (Fig. 7b). Expression of Hes1 and Hes5, which are also regulated by Notch1 (Chojnacki et al., 2003), was not significantly affected by the MCAO in either CNTF−/− or wildtype mice (Fig. 7b).

Negative regulators of stroke-induced SVZ neurogenesis counteract CNTF activity

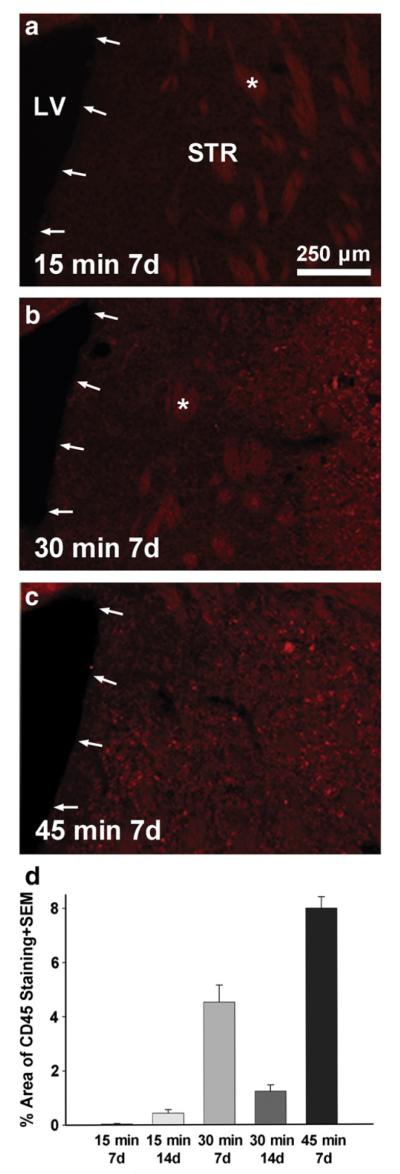

A time course analysis of CNTF expression showed that it was already increased 3-fold by day 5 after MCAO (Fig. 8a). However, the SVZ proliferation was only increased by ~20%, as measured by the number of BrdU+ nuclei or by qPCR for the general proliferation marker Ki67 and for the transient amplifying C cell marker, EGFR (Fig. 8a). At 12 days following MCAO, the amount of proliferation increased much more, by approximately two fold. This suggests that there are inhibitory conditions which counteract the pro-neurogenic effects of the earlier increased CNTF. We therefore measured expression of the family members IL-6 (Vallieres et al., 2002) and LIF (Bauer and Patterson, 2006), and the inflammatory cytokine, TNFα (Iosif et al., 2006, 2008), which can reduce adult neurogenesis in vivo. IL-6 expression levels were very high at 1 day and returned to baseline levels at 5 days post-MCAO (Fig. 8b) suggesting that it does not regulate neurogenesis at the later times. IL-6 expression was not significantly affected by the 15 min MCAO at 1 day (1.82±0.69 versus sham 1.00±0.09, p=0.33, n=5 and 4). LIF and TNFα both showed increased levels at 1 and 5 days compared to sham-operated mice, and decreased to baseline levels at 12 days. The increase in these pro-inflammatory cytokines suggested that inflammatory responses in the SVZ and neighboring striatum could have reduced the expected increase in neurogenesis 1 week after MCAO. In astrocyte–neuron cocultures, addition of 20 ng/ml TNFα or 10 ng/ml LIF for 24 h did not significantly change CNTF expression (qPCR from 3 independent experiments, data not shown), suggesting that the inhibition could be caused by different mechanisms competing with those that are downstream of CNTF. Sections stained for the general leukocyte marker CD45 showed increasing proximity and amount to the SVZ with increasing MCAO occlusion time (Fig. 9a–c). Of note was the inflammation within the SVZ seen in the 45 min MCAO group at 7 days (Fig. 9c). The 15 min MCAO values were greater at 14 than at 7 days (p<0.05, suggesting a need for inflammatory signaling to increase neurogenesis (see BrdU values in Fig. 3a). Inflammation was much greater in the 45 min MCAO group than the 30 min MCAO group at 7 days (p<0.01), suggesting that too much inflammation reduces the neurogenic response (compare to Fig. 3a). This is also suggested by the findings in the 30 min MCAO group, where inflammation was less pronounced at 14 relative to 7 days (Fig. 9d; p<0.01), consistent with the reduced TNFα levels at later post-MCAO times (Fig. 8b), but when neurogenesis was increased greatly (Fig. 3a).

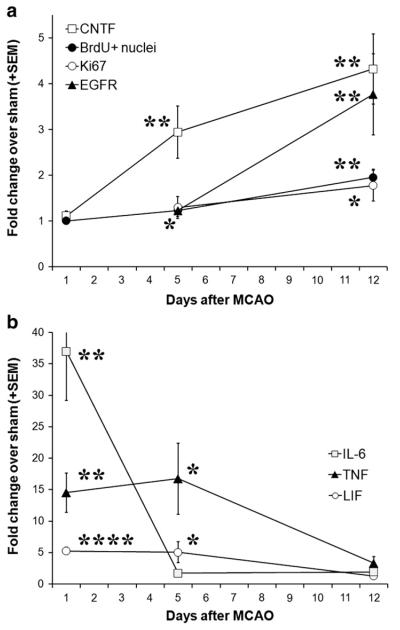

Fig. 8.

The neurogenic effects of CNTF appear to be counteracted by inflammatory cytokines early following stroke. (a) In C57BL/6 mice, CNTF expression was increased about 3-fold by day 5 after MCAO, but SVZ proliferation was only increased by ~20%, as measured by qPCR for the proliferation marker Ki67 and for the transient amplifying C cell marker, EGFR. The number of BrdU+ cells is from another set of mice shown in Fig. 3a for comparison to Ki67. At 12 days following MCAO, when CNTF levels had increased from 3- to 4-fold, the amount of proliferation had increased much more, to approximately 2-fold of sham. This suggests that at earlier on after MCAO, the effects of CNTF are inhibited. (b) Expression of inflammatory cytokines with known inhibitory effects on neurogenesis was measured by qPCR in the same tissues as in (a). IL-6 expression was increased 37-fold at 1 day and returned to baseline levels at 5 days post-MCAO, suggesting that it does not reduce the effects of CNTF at 5 days post-MCAO. LIF and TNFα both were increased about 5-fold and 15-fold, respectively, at 1 and 5 days compared to sham-operated mice, and decreased to baseline levels at 12 days (n of 1, 5, 12 day MCAO: 5, 4, 4; sham: 5, 5, 5). *p<0.05, **p<0.01,****p<0.0001 compared to sham.

Fig. 9.

Inflammation reaches the SVZ following severe ischemic injury MCAO. Coronal sections through the SVZ (arrows) and striatum (STR) stained for the general leukocyte marker CD45 show paucity of inflammation close to the SVZ following a 15 min MCAO (a). After a 30 min MCAO (b), the inflammatory response appeared closer to the SVZ. After a 45 min MCAO (c) CD45+ cells were seen in most of the brain as well as within the SVZ. (d) The area of CD45+ (total red pixels minus the non-specific staining of white matter bundles through the striatum, some indicated by an asterisk) was measured and calculated as a percentage of the total striatal area shown. Note that both very low (15 min MCAO) and very high levels (45 min MCAO) of inflammation correspond to low increases in proliferation in the SVZ as shown in the same mice in Fig. 3a. LV=lateral ventricle.

Discussion

CNTF mediates stroke-induced SVZ neurogenesis

Our main results suggest that CNTF plays a crucial role in the neurogenic response to focal ischemic MCAO of the neighboring striatum. The increase in SVZ proliferation was related to CNTF expression in C57BL/6 mice, where a 30 min MCAO caused both an increase in BrdU+SVZ nuclei and CNTF, whereas the 15 min MCAO had no or only small effects. The lack of a significant proliferative response in CNTF−/− mice suggests that all of the response is normally mediated by CNTF. This central role is also supported by the finding that expression of other CNTF family members IL-6 or LIF, which both signal through gp130 (Bauer et al., 2007; Suzuki et al., 2009), showed no or only a small amount of compensation, respectively, for the lack of CNTF in CNTF−/− mice. Also, the time course of LIF or IL-6 expression in the SVZ of C57BL/6 mice after a 30 min MCAO was not predictive of the stroke-induced neurogenic response. LIF, but not CNTF, appears to be involved during the neurogenic response induced by perinatal ischemia (Covey and Levison, 2007). CNTF levels in the CNS increase only postnatally (Stockli et al., 1989) and it is possibly that CNTF takes over the former role played by LIF.

CNTF as a potential regulable endogenous target after stroke

Our finding that CNTF increases after MCAO is consistent with other studies that show large increases in CNTF mRNA in the cortex of MCAO injured rats (Lin et al., 1998). Here, we show the need for increased CNTF expression close to or within the SVZ for it to enhance neurogenesis. CNTF in the SVZ is produced by the resident astrocytes (Yang et al., 2008), a cell type which typically does not die after stroke and thus remains available as a growth factor factory in degenerative conditions. The finding that CNTF mediates most or all of the increased proliferation following ischemic stroke is important as it suggests that its production remains amenable to pharmacological induction. Previously, we have shown that a D2 dopamine agonist (Yang et al., 2008) and a P2X7 antagonist (Kang et al., unpublished results) can increase CNTF expression in the SVZ of naive adult mice. It will be important to determine whether such drugs can be used to produce more neurons for replacement of lost neurons after stroke.

The mechanisms that lead to the stroke-induced increases in CNTF remain to be defined. CNTF most likely increases in the SVZ itself because CNTF expression is much greater in the SVZ than the neighboring striatum (Yang et al., 2008) and our gene expression measurements were made within tissue that contains the SVZ but not the injured striatal tissue. The slow increase in the SVZ compared to the almost immediate response in the striatum (Kang et al., 2012) suggests that the SVZ response is not due to the rapid loss of neurons or ischemia in the SVZ. The lack of a clear increase in CNTF expression after the 15 min MCAO, where the distance of injured tissue to the SVZ is large compared to the 30 min MCAO, suggests that diffusible factors are involved. If so, this would provide a promising opportunity because the receptors of such diffusible agents could be targeted with pharmacological drugs to increase CNTF, thus increasing SVZ neurogenesis. The lack of CD45+ cells close to the SVZ after a 15 min MCAO suggests that pro-inflammatory mechanisms might be involved. One inflammatory regulator of CNTF might be the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 whose expression was transiently increased at 24 h in the SVZ following the 30 min (Fig. 8b) but not the 15 min MCAO. IL-6 can up-regulate CNTF mRNA in dorsal root ganglion culture (Shuto et al., 2001).

CNTF regulates SVZ neurogenesis possibly by inducing FGF2

Our data also suggest some of the likely mechanisms that underlie the neurogenic effects of CNTF. The CNTF-selective alpha receptors in the SVZ are exclusively present on GFAP-positive cells which mainly are astrocytes but might also include the much sparser neural stem cells (Emsley and Hagg, 2003). Others have shown in vitro and in vivo that, in the presence of EGF, CNTF stimulates SVZ neural stem cell self-renewal via Notch1 signaling (Chojnacki et al., 2003). However, this mechanism does not appear to be affected by the MCAO-induced CNTF. The neural stem cell marker Sox2 (Ellis et al., 2004) and the low EGF levels were unaltered in the SVZ. Although Notch1 expression was increased in the SVZ following MCAO, this did not result in Notch signaling as the expression of downstream Hes1 or Hes5, both promoters of self-renewal (Nakamura et al., 2000; Ohtsuka et al., 2001), were not significantly changed. Notch1 expression was also increased in the CNTF−/− mice after MCAO, suggesting that CNTF was not involved. LIF was increased in the SVZ of both CNTF−/− mice and their littermate controls, and might have caused the increase in Notch1 expression as it does in the neonate SVZ (Covey and Levison, 2007) and in embryonic neuroepithelial cells (Faux et al., 2001).

Our data support the idea that MCAO-induced CNTF affects the rapidly proliferating transient amplifying progenitor cells, also named C cells. Expression of EGFR, which is present on C cells (Doetsch et al., 2002), was increased 4 fold. Moreover, Mash1, which is involved in the initial step from neural stem cell to progenitor transition (Torii et al., 1999), was increased by the MCAO. However, the effect of CNTF on the C cells was probably not mediated by the induction of Mash1, as this increase was not significantly different between CNTF−/− and wildtype mice.

Since the CNTF receptor alpha is only expressed by GFAP-positive cells, the mechanism underlying the effects of MCAO-induced CNTF on C cells most likely involves a different releasable astroglial factor. FGF2 is another major regulator of neurogenesis in the SVZ (Mudo et al., 2009; Zheng et al., 2004). FGF2 is expressed and released by GFAP-positive cells of SVZ but is not present in proliferating precursor cells (Mudo et al., 2009). Our finding that FGF2 expression in the SVZ is increased after MCAO in wildtype but not in CNTF−/− mice suggests that its induction is CNTF-dependent. The mechanisms by which FGF-2 might affect the progenitor populations remain to be resolved (Mudo et al., 2009). Notch1 and Mash1 are probably not involved as they were increased in the absence of an increase of FGF2 in the CNTF−/− mice after MCAO. FGFR-1 and FGFR-2 are expressed in the C cells (Frinchi et al., 2008; Mudo et al., 2009), as well as in the self-renewing neural stem cells. FGF2, in contrast to EGF, promotes an increase in the number of newborn neurons in the SVZ (Kuhn et al., 1997). We had previously found that CNTF increases SVZ proliferation without changing the normal neuronal cell-fate decision (Emsley and Hagg, 2003). Others have shown that a severe 60 min MCAO injury in mice, which our data suggest would have injured the SVZ, produces predominantly astrocytes from the SVZ migrating to the striatum after 14 days (Li et al., 2010). Our data suggest that after a less severe 30 min injury most additional new cells in the SVZ, as identified by BrdU, become dcx-positive neuroblasts at 14 days post-injury. This suggests that as long as the stroke region does not reach the SVZ, stroke-induced CNTF-FGF2 also favors normal neuronal fate decisions. Thus, the FGF2-mediated effects of endogenous CNTF may make it a good target for inducing production of new neurons. Moreover, CNTF is predominantly expressed in the nervous system (Stockli et al., 1989) making it a nervous system-selective endogenous target. Although we did not test whether the stroke-induced neurogenesis was beneficial, others have shown in rats and mice that it correlates with better behavioral outcomes (Ishibashi et al., 2007; Li et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2004).

Stroke-induced inflammation and LIF may compete with the neurogenic activity of CNTF

The discrepancy in high CNTF expression in the SVZ at 1 week following MCAO and the low increase in proliferation may be explained by competing inhibitory mechanisms at that time. The temporal pattern of TNFα expression, which others have also seen after stroke (Lambertsen et al., 2005, 2007), would suggest that it is one of the major inhibitors. TNFα has been shown to reduce progenitor SVZ and hippocampal proliferation through the TNF receptor-1 (Iosif et al., 2008; Iosif et al., 2006). Our astrocyte culture data suggest that TNFα does not affect CNTF expression but likely inhibits proliferation via other mechanisms. The anti-neurogenic effects of irradiation-induced inflammation have been well-documented (Monje et al., 2003; Voloboueva et al., 2010). Our results suggest that MCAO-induced inflammation close to and within the SVZ prevented the neurogenic response to MCAO. However, our 15 min MCAO data showing low CD45, low CNTF and low neurogenesis suggests that a delicate balance between beneficial and detrimental inflammation determines the extent of stroke-induced neurogenesis.

LIF reportedly has pro-neurogenic activities for olfactory epithelial NSCs (Bauer and Patterson, 2006; Bauer et al., 2003), and after perinatal ischemia (Covey and Levison, 2007). On the other hand, our data are more consistent with the finding that LIF leads to increased self-renewal of NSC in the brain at the expense of neurogenesis (Bauer and Patterson, 2006). Like our data in the SVZ, CNTF expression in the peri-ischemic region is gradually increased to 14 days (Lin et al., 1998), but the expression pattern of LIF peaks at 24 h and lasts 7 days after stroke (Suzuki et al., 1999, 2000). Thus, it is possible that LIF initiates NSC self-renewal during the first week after MCAO and, due to its reduced expression into week 2, only then allows CNTF to robustly increase neurogenesis. The only difference between LIF and CNTF signaling is the requirement for CNTFα receptor to activate the LIFβ receptor/gp 130 dimer. How these differences would explain the different neurogenic properties of CNTF and LIF is not clear. A better understanding of the interplay between and CNTF, LIF and TNFα and their receptors is expected to help us design pharmacological treatments to optimize neurogenesis following stroke.

Very selective conditions are needed for stroke-induced SVZ neurogenesis in mice

The second main contribution of this study is to provide a platform for further studies by defining very specific MCAO conditions and stereological counting methods. The current data in C57BL/6 mice show that the conditions for a robust increase in SVZ neurogenesis are very specific and require a 30 min MCAO and a 2 week period afterwards. This is very different from the neurogenic conditions seen in rats where of SVZ proliferation increases by 35% within 2 days and increases even more to 7–14 days after MCAO (Jin et al., 2001; Parent et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2001). The literature in mice is not extensive and seems discrepant, where MCAO is reported to markedly increase proliferating SVZ cells already after 1 day, lasting for at least 14 days (Tanaka et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2007) or reduces SVZ proliferation after 3 days with a return to normal levels at 7 days (Tsai et al., 2006). Also, the reported MCAO times of 45 or more minutes or of small cortical injuries caused by distal MCAO seem to contradict our findings that extensive or small injuries, respectively, do not increase SVZ proliferation. We propose that the technical difficulties in mice related to MCAO filament sizes as well as the lack of unbiased stereological counting methods may explain the apparent discrepancies with our study. Our study seems to be the first one in mice to use unbiased stereology covering the entire SVZ of the anterior horns of the lateral ventricles. In contrast to rat, the infarct size of mice after MCAO seems to be much more sensitive to the diameter of the monofilament, perhaps because of the very small arteries in mice. Previously, a relationship between body weight and the diameter of monofilament needed to successfully achieve sufficient occlusion was reported (Hata et al., 1998). Here, we show that use of DOCCOL 0.21 mm tipped filaments can be applied to a greater weight range and are much more reliable than filaments made in the laboratory. The occlusion time is the most important factor determining the extent of the ischemic injury and our results are in line with those of another study (McColl et al., 2004). We do note that accurately applied MCAO of 30 min results in severe neurological deficits and without intensive care results in high mortality rates. The 45 min occlusion caused high mortality irrespectively. In one study (Li et al., 2010), survival after a 60 min MCAO was possible by keeping mice on a heating pad for the first week (Dr. Lee Anna Cunningham, personal communication). Our data show that long occlusion times most likely injure the SVZ and reduce the MCAO-induced proliferative response. Lastly, the use of Doppler flowmetry is essential to ensure confidence in inclusion of mice in a study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that endogenous CNTF in the mouse SVZ mediates stroke-induced neurogenesis, possibly by inducing FGF2 and mainly affecting C cell proliferation, providing a valid target for pharmacological drug development to further stimulate neurogenesis. We have shown proof of concept that such a systemic drug approach utilizing endogenous CNTF can induce neurogenesis in the naive mouse (Yang et al., 2008). We also suggest that pro-inflammatory factors, including TNFα, are inhibitory to neurogenesis during the 7 days post-injury and that their inhibition may further increase neurogenesis for treatment after stroke. Lastly, we find that focal ischemic injury in mice by MCAO enhances SVZ neurogenesis only under very specific conditions, involving more severe injuries and being much delayed compared to rats. Having defined these conditions in mice will help the neurogenesis field to move forward in a much more consistent and reliable manner by assessing the multitude of genetically modified mice currently available.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This paper is dedicated to Rollie Reid, our friend and colleague, who passed away June 22, 2011 at the age of 38. We will greatly miss him. We wish to thank Erin Welsh, Hillary Conway, Vicky Tran and Yunshi Long for their excellent technical assistance.

Funding This work was supported by NIH grants AG29493 and P30 GM103507, Norton Healthcare, and the Commonwealth of Kentucky Challenge for Excellence. The sponsors had no input on the paper.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- BrdU

5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine

- CC

corpus callosum

- CD45

cluster of differentiation number 45 or leukocyte common antigen

- CNTF

ciliary neurotrophic factor

- Dll3

delta-like 3

- ECA

external carotid artery

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- EPO

erythropoietin

- FGF2

fibroblast growth factor 2

- gp130

glycoprotein 130

- Hes1

hairy and enhancer of split 1

- Hes5

hairy and enhancer of split 5

- IFNγ

interferon-gamma

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor 1

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- Ki67

proliferation-associated protein named for its Ki-67 motif

- LIF

leukemia inhibitory factor

- LV

lateral ventricle

- Mash1

mouse achaete-scute homolog 1

- MCA

middle cerebral artery

- MCAO

middle cerebral artery occlusion

- MSI1

musashi-1

- PB

phosphate buffer

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- qPCR

quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- RT

reverse transcription

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- Sox2

sex determining region Y-box 2

- SVZ

subventricular zone

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Disclosures The authors have no financial disclosures.

Appendix A. Supplementary data Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2012.08.020.

References

- Arvidsson A, Collin T, Kirik D, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. Neuronal replacement from endogenous precursors in the adult brain after stroke. Nat. Med. 2002;8:963–970. doi: 10.1038/nm747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker SA, Baker KA, Hagg T. Dopaminergic nigrostriatal projections regulate neural precursor proliferation in the adult mouse subventricular zone. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004;20:575–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer S, Patterson PH. Leukemia inhibitory factor promotes neural stem cell self-renewal in the adult brain. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:12089–12099. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3047-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer S, Rasika S, Han J, Mauduit C, Raccurt M, Morel G, et al. Leukemia inhibitory factor is a key signal for injury-induced neurogenesis in the adult mouse olfactory epithelium. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:1792–1803. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01792.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer S, Kerr BJ, Patterson PH. The neuropoietic cytokine family in development, plasticity, disease and injury. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:221–232. doi: 10.1038/nrn2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Hur T, Ben-Menachem O, Furer V, Einstein O, Mizrachi-Kol R, Grigoriadis N. Effects of proinflammatory cytokines on the growth, fate, and motility of multipotential neural precursor cells. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2003;24:623–631. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns TC, Verfaillie CM, Low WC. Stem cells for ischemic brain injury: a critical review. J. Comp. Neurol. 2009;515:125–144. doi: 10.1002/cne.22038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielnicki E, Benraiss A, Economides AN, Goldman SA. Adenovirally expressed noggin and brain-derived neurotrophic factor cooperate to induce new medium spiny neurons from resident progenitor cells in the adult striatal ventricular zone. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:2133–2142. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1554-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chojnacki A, Shimazaki T, Gregg C, Weinmaster G, Weiss S. Glycoprotein 130 signaling regulates Notch1 expression and activation in the self-renewal of mammalian forebrain neural stem cells. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:1730–1741. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01730.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey MV, Levison SW. Leukemia inhibitory factor participates in the expansion of neural stem/progenitors after perinatal hypoxia/ischemia. Neuroscience. 2007;148:501–509. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUROSCIENCE.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetsch F, Petreanu L, Caille I, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. EGF converts transit-amplifying neurogenic precursors in the adult brain into multipotent stem cells. Neuron. 2002;36:1021–1034. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis P, Fagan BM, Magness ST, Hutton S, Taranova O, Hayashi S, et al. SOX2, a persistent marker for multipotential neural stem cells derived from embryonic stem cells, the embryo or the adult. Dev. Neurosci. 2004;26:148–165. doi: 10.1159/000082134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley JG, Hagg T. Endogenous and exogenous ciliary neurotrophic factor enhances forebrain neurogenesis in adult mice. Exp. Neurol. 2003;183:298–310. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esneault E, Pacary E, Eddi D, Freret T, Tixier E, Toutain J, et al. Combined therapeutic strategy using erythropoietin and mesenchymal stem cells potentiates neurogenesis after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1552–1563. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faux CH, Turnley AM, Epa R, Cappai R, Bartlett PF. Interactions between fibroblast growth factors and Notch regulate neuronal differentiation. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:5587–5596. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05587.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frinchi M, Bonomo A, Trovato-Salinaro A, Condorelli DF, Fuxe K, Spampinato MG, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-2 and its receptor expression in proliferating precursor cells of the subventricular zone in the adult rat brain. Neurosci. Lett. 2008;447:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata R, Mies G, Wiessner C, Fritze K, Hesselbarth D, Brinker G, et al. A reproducible model of middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice: hemodynamic, biochemical, and magnetic resonance imaging. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:367–375. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199804000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iosif RE, Ekdahl CT, Ahlenius H, Pronk CJ, Bonde S, Kokaia Z, et al. Tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 is a negative regulator of progenitor proliferation in adult hippocampal neurogenesis. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:9703–9712. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2723-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iosif RE, Ahlenius H, Ekdahl CT, Darsalia V, Thored P, Jovinge S, et al. Suppression of stroke-induced progenitor proliferation in adult subventricular zone by tumor necrosis factor receptor 1. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1574–1587. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi S, Kuroiwa T, Sakaguchi M, Sun L, Kadoya T, Okano H, et al. Galectin-1 regulates neurogenesis in the subventricular zone and promotes functional recovery after stroke. Exp. Neurol. 2007;207:302–313. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin K, Minami M, Lan JQ, Mao XO, Batteur S, Simon RP, et al. Neurogenesis in dentate subgranular zone and rostral subventricular zone after focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:4710–4715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081011098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin K, Sun Y, Xie L, Childs J, Mao XO, Greenberg DA. Post-ischemic administration of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor (HB-EGF) reduces infarct size and modifies neurogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:399–408. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200404000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin K, Wang X, Xie L, Mao XO, Zhu W, Wang Y, et al. Evidence for stroke-induced neurogenesis in the human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:13198–13202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603512103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko Y, Sakakibara S, Imai T, Suzuki A, Nakamura Y, Sawamoto K, et al. Musashi1: an evolutionally conserved marker for CNS progenitor cells including neural stem cells. Dev. Neurosci. 2000;22:139–153. doi: 10.1159/000017435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SS, Keasey MP, Cai J, Hagg T. Loss of neuron-astroglial interaction rapidly induces protective CNTF expression after stroke in mice. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:9277–9287. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1746-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernie SG, Parent JM. Forebrain neurogenesis after focal Ischemic and traumatic brain injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010;37:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch M, Trautmann N, Ernst M, Hofmann HD. Involvement of gp130-associated cytokine signaling in Muller cell activation following optic nerve lesion. Glia. 2010;58:768–779. doi: 10.1002/glia.20961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn HG, Winkler J, Kempermann G, Thal LJ, Gage FH. Epidermal growth factor and fibroblast growth factor-2 have different effects on neural progenitors in the adult rat brain. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:5820–5829. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05820.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambertsen KL, Meldgaard M, Ladeby R, Finsen B. A quantitative study of microglial-macrophage synthesis of tumor necrosis factor during acute and late focal cerebral ischemia in mice. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:119–135. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambertsen KL, Clausen BH, Fenger C, Wulf H, Owens T, Dagnaes-Hansen F, et al. Microglia and macrophages express tumor necrosis factor receptor p75 following middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice. Neuroscience. 2007;144:934–949. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Harms KM, Ventura PB, Lagace DC, Eisch AJ, Cunningham LA. Focal cerebral ischemia induces a multilineage cytogenic response from adult subventricular zone that is predominantly gliogenic. Glia. 2010;58:1610–1619. doi: 10.1002/glia.21033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Siegel M, Yuan M, Zeng Z, Finnucan L, Persky R, et al. Estrogen enhances neurogenesis and behavioral recovery after stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:413–425. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TN, Wang PY, Chi SI, Kuo JS. Differential regulation of ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) and CNTF receptor alpha (CNTFR alpha) expression following focal cerebral ischemia. Mol. Brain Res. 1998;55:71–80. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macas J, Nern C, Plate KH, Momma S. Increased generation of neuronal progenitors after ischemic injury in the aged adult human forebrain. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:13114–13119. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4667-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McColl BW, Carswell HV, McCulloch J, Horsburgh K. Extension of cerebral hypoperfusion and ischaemic pathology beyond MCA territory after intraluminal filament occlusion in C57Bl/6J mice. Brain Res. 2004;997:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monje ML, Toda H, Palmer TD. Inflammatory blockade restores adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Science. 2003;302:1760–1765. doi: 10.1126/science.1088417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudo G, Bonomo A, Di Liberto V, Frinchi M, Fuxe K, Belluardo N. The FGF-2/FGFRs neurotrophic system promotes neurogenesis in the adult brain. J. Neural Transm. 2009;116:995–1005. doi: 10.1007/s00702-009-0207-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Sakakibara S, Miyata T, Ogawa M, Shimazaki T, Weiss S, et al. The bHLH gene hes1 as a repressor of the neuronal commitment of CNS stem cells. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:283–293. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00283.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuka T, Sakamoto M, Guillemot F, Kageyama R. Roles of the basic helix-loop-helix genes Hes1 and Hes5 in expansion of neural stem cells of the developing brain. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:30467–30474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102420200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent JM, Vexler ZS, Gong C, Derugin N, Ferriero DM. Rat forebrain neurogenesis and striatal neuron replacement after focal stroke. Ann. Neurol. 2002;52:802–813. doi: 10.1002/ana.10393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schabitz WR, Steigleder T, Cooper-Kuhn CM, Schwab S, Sommer C, Schneider A, et al. Intravenous brain-derived neurotrophic factor enhances poststroke sensorimotor recovery and stimulates neurogenesis. Stroke. 2007;38:2165–2172. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.477331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuto T, Horie H, Hikawa N, Sango K, Tokashiki A, Murata H, et al. IL-6 upregulates CNTF mRNA expression and enhances neurite regeneration. Neuroreport. 2001;12:1081–1085. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200104170-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockli KA, Lottspeich F, Sendtner M, Masiakowski P, Carroll P, Gotz R, et al. Molecular cloning, expression and regional distribution of rat ciliary neurotrophic factor. Nature. 1989;342:920–923. doi: 10.1038/342920a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Jin K, Xie L, Childs J, Mao XO, Logvinova A, et al. VEGF-induced neuroprotection, neurogenesis, and angiogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:1843–1851. doi: 10.1172/JCI17977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Tanaka K, Nogawa S, Nagata E, Ito D, Dembo T, et al. Temporal profile and cellular localization of interleukin-6 protein after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:1256–1262. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199911000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Tanaka K, Nogawa S, Ito D, Dembo T, Kosakai A, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of leukemia inhibitory factor after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:661–668. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200004000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Tanaka K, Suzuki N. Ambivalent aspects of interleukin-6 in cerebral ischemia: inflammatory versus neurotrophic aspects. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:464–479. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Tanaka R, Liu M, Hattori N, Urabe T. Cilostazol attenuates ischemic brain injury and enhances neurogenesis in the subventricular zone of adult mice after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 2010;171:1367–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torii M, Matsuzaki F, Osumi N, Kaibuchi K, Nakamura S, Casarosa S, et al. Transcription factors Mash-1 and Prox-1 delineate early steps in differentiation of neural stem cells in the developing central nervous system. Development. 1999;126:443–456. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.3.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai PT, Ohab JJ, Kertesz N, Groszer M, Matter C, Gao J, et al. A critical role of erythropoietin receptor in neurogenesis and post-stroke recovery. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:1269–1274. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4480-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tureyen K, Vemuganti R, Bowen KK, Sailor KA, Dempsey RJ. EGF and FGF-2 infusion increases post-ischemic neural progenitor cell proliferation in the adult rat brain. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:1254–1263. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000186040.96929.8a. (discussion 1254–63) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela DM, Murphy AJ, Frendewey D, Gale NW, Economides AN, Auerbach W, et al. High-throughput engineering of the mouse genome coupled with high-resolution expression analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:652–659. doi: 10.1038/nbt822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallieres L, Campbell IL, Gage FH, Sawchenko PE. Reduced hippocampal neurogenesis in adult transgenic mice with chronic astrocytic production of interleukin-6. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:486–492. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-02-00486.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voloboueva LA, Lee SW, Emery JF, Palmer TD, Giffard RG. Mitochondrial protection attenuates inflammation-induced impairment of neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:12242–12251. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1752-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Zhang R, Chopp M. Treatment of stroke with erythropoietin enhances neurogenesis and angiogenesis and improves neurological function in rats. Stroke. 2004;35:1732–1737. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000132196.49028.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Jin K, Mao XO, Xie L, Banwait S, Marti HH, et al. VEGF-overexpressing transgenic mice show enhanced post-ischemic neurogenesis and neuromigration. J. Neurosci. Res. 2007;85:740–747. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtowicz JM, Kee N. BrdU assay for neurogenesis in rodents. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:1399–1405. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan YP, Sailor KA, Vemuganti R, Dempsey RJ. Insulin-like growth factor-1 is an endogenous mediator of focal ischemia-induced neural progenitor proliferation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006;24:45–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Arnold SA, Habas A, Hetman M, Hagg T. Ciliary neurotrophic factor mediates dopamine D2 receptor-induced CNS neurogenesis in adult mice. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:2231–2241. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3574-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZG, Chopp M. Neurorestorative therapies for stroke: underlying mechanisms and translation to the clinic. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:491–500. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70061-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang RL, Zhang ZG, Zhang L, Chopp M. Proliferation and differentiation of progenitor cells in the cortex and the subventricular zone in the adult rat after focal cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 2001;105:33–41. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng W, Nowakowski RS, Vaccarino FM. Fibroblast growth factor 2 is required for maintaining the neural stem cell pool in the mouse brain subventricular zone. Dev. Neurosci. 2004;26:181–196. doi: 10.1159/000082136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.