Abstract

Small molecule-DNA hybrids with only two parallel DNA duplexes (rSMDH2) displayed sharper melting profiles compared to unmodified DNA duplexes, consistent with predictions from neighboring-duplex theory. Using adjusted thermodynamic parameters obtained from a coarse-grain dynamic simulation, the experimental data fit well to an analytical model.

DNA-hybrid materials have been explored in a wide range of research areas such as sensors and actuators,1,2 molecular electronics,3 template synthesis,4,5 and computing.6-11 In diagnostics, DNA-linked gold nanoparticle (GNP)12 and comb-like polymer13 aggregates possess a unique switch-like melting property, which has been utilized to distinguish single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). This switch-like melting phenomenon can be explained by a “neighboring-duplex/effective-concentration” (ND/EC) model,14 which predicts an enhanced melting temperature (Tm) and sharp melting due to two effects: 1) entropic constraints associated with the melting of structures in which the tethered DNA's have a higher effective concentration than when they are free in solution, and 2) an increase in the effective ion concentration between neighboring duplexes that leads to higher overall stability of fully hybridized structures and cooperative thermal melting.15 This model, which has been verified using coarse-grain molecular dynamics (CGMD) simulations,14 predicts that stabilization can be observed with as few as 2-3 parallel DNA duplexes, giving rise to sharper melting transitions in DNA-linked nanoparticle12 and comb-like polymer13 aggregates than that observed for double-stranded DNA duplex.16,17

We recently reported the synthesis and cooperative melting behavior of a small molecule-DNA hybrid containing only three DNA duplexes (SMDH3) around a rigid (r) small-molecule core (C).18 Herein, we report the cooperative melting of SMDH2, possessing only two closely-associated double-stranded DNAs, with or without a rigid core. Using adjusted thermodynamic parameters obtained from coarse-grain molecular dynamics simulations, the experimental data fit well to an analytical model where the melting of these dimeric duplexes is considered as two distinct steps where most of the entropy is released in the second step.

rSMDH2 3 and 3′ (Figure 1, 3 = 3′-A-5′-T3CT3-3′-B-5′, 3′ = 3′-A′-5′-T3CT3-3′-B′-5′) containing two asymmetric strands (one of the strands is the reverse sequence of the other) were designed to facilitate only the formation of cage-like dimers and avoid face-to-face bulge-containing DNA structures (Figure S3 in Supporting Information (SI)). Synthesis of asymmetric rSMDH2s was achieved by adding the phosphoramidite core 119 to the initial DNA arm grown from the surface of a controlled porosity glass bead (CPG), followed by synthesis of the second arm via 3′-phosphoramidite chemistry (Figure 1). As an improvement from our previous synthesis,18 we added an extra ethylene glycol (CH2CH2O) linker between the core and the DNA strand; this makes the products more stable during the DMT-on reverse phase HPLC purification. To evaluate the effect of the core C on melting behavior, we also prepared analogous SMDH2s where the arms are simply linked together via 6-base pair ss-DNA TTTTTT sequence (T6 spacer; i.e., 3′-A-5′-T6-3′-B-5′ or A-T6-B for short).

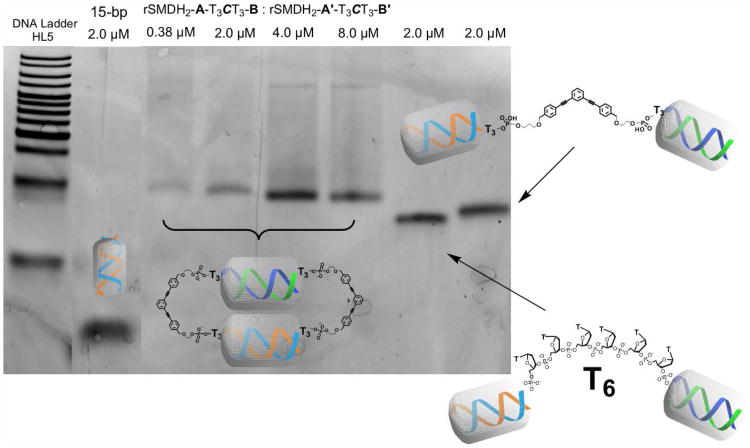

Figure 1.

Synthesis of rSMDH2-A-T3CT3-B and its dimeric structures 4-6 (dimeric cages 5 and 6 are formed using rSMDH2 an unmodified DNA with T6 linker).

Hybridization of rSMDH2s was performed by combining equimolar amounts of two complementarily functionalized rSMDH2s in phosphate buffer at 25 °C, annealing the hybridized mixture at 85 °C for 10 min, and allowing it to cool to room temperature over 4 h. The melting profile of the hybridized mixture was obtained by heating the samples from 20 to 70 °C at a rate of 1 °C per minute while monitoring the increase in UV-vis absorbance at 260 nm at 01°C intervals. For comparison, we also formed cage-like structures 5 and 6, from rSMDH2 3 with the complementary A′-T6-B′ and from A-T6-B:A′-T6-B′, respectively (Figure 1).

Similar to the previously reported rSMDH3 experiment,18 non-denaturing PAGE-gel analyses of the hybridized 0.38-2 μM solutions containing caged dimers 4 and 6 (Figure 2, see also Figures S8 and S9 in SI) displayed sharp bands. However, at higher concentrations (4-16 μM), solutions of these caged dimers show new bands and smearing, corresponding to higher cyclic and oligomeric stuctures, respectively.

Figure 2.

Non-denaturing PAGE-gel image (10%) of DNA duplexes and hybrids. From left to right: lane 1 = HL5 DNA ladder, lane 2 = A:A′ (2 μM), lane 3-6 = rSMDH2-A-T3CT3-B:rSMDH2-A′-T3CT3-B′ (0.38 to 8 μM), lane 7 = A:A′-T6-B′:B (2.0 μM), lane 8 = A:rSMDH2-A′-T3CT3-B′:B (2.0 μM).

The neighboring-duplex/effective concentration model15 predicts that when an aggregate possesses two or more parallel DNA duplexes in close proximity (25-40 Å),17 its melting point (Tm) increases and its melting profile sharpens. Consistent with this conjecture, the rSMDH2 dimer 4 (3:3′) displayed a sharper melting profile (full width at half maximum (fwhm) = 6.3 ± 0.2 °C) and a higher melting temperature (Tm = 43.5 ± 0.4 °C) compared to the A:A′ unmodified 15 base-pair DNA duplex (fwhm = 10.6 ± 0.1 °C, Tm = 41.3 ± 0.1 °C) (Table 1). Surprisingly, dimers 5 and 6 (Figures 3), where either one or both partners do not have a rigid core linking the two DNA arms together, also show similarly sharp melting profiles and higher Tm (Table 1, entries 11-16) as 4. This observation suggests that as long as the linkers are short enough to keep the DNA arms in close proximity, cooperative melting can occur readily in the absence of a rigid linker.

Table 1.

Melting data for 15-bp DNA duplexes (A:A′), , caged- (4, 5, 6) and hairpin-like (8) dimers formed by unmodified DNA and rSMDH2 hybrids.

| entry | hybridization mixture | [NaCl] (mM)a | Tm (°C) | fwhm (°C) | Nc (± 0.1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A:A′ b | 75 | 35.6 ± 0.4 | 10.3 ± 0.4 | - |

| 2 | A:A′ b | 150 | 40.9 ± 0.2 | 10.6 ± 0.1 | - |

| 3 | A:A′ b | 300 | 45.3 ± 0.4 | 10.8 ± 0.3 | - |

| 4 | A:A′ b,c | 300 | 45.8 | 10.5 | - |

| 5 | A: A′ -T6-B′:B d | 75 | 36.4 ± 0.1 | 10.2 ± 0.1 | 1.0 |

| 6 | A: A′ -T6-B′:B d | 150 | 41.0 ± 0.3 | 10.3 ± 0.1 | 1.0 |

| 7 | A: A′ -T6-B′:B d | 300 | 46.5 ± 0.2 | 10.3 ± 0.3 | 1.0 |

| 8 | 4 b | 75 | 37.5 ± 0.2 | 6.3 ± 0.2 | 1.7 |

| 9 | 4 b | 150 | 43.5 ± 0.4 | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 1.8 |

| 10 | 4 b | 300 | 49.1 ± 0.3 | 7.5 ± 0.1 | 1.6 |

| 11 | 5 b | 75 | 36.9 ± 0.1 | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 2.0 |

| 12 | 5 b | 150 | 43.5 ± 0.1 | 5.8 ± 0.1 | 2.1 |

| 13 | 5 b | 300 | 47.9 ± 0.1 | 6.2 ± 0.1 | 1.8 |

| 14 | 6 b | 75 | 36.5 ± 0.1 | 6.0 ± 0.1 | 1.8 |

| 15 | 6 b | 150 | 42.2 ± 0.1 | 6.1 ± 0.1 | 2.0 |

| 16 | 6 b | 300 | 48.5 ± 0.1 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 1.8 |

| 17 | 6 b,c | 300 | 48.8 | 4.7 | - |

| 18 | 8 b,e | 75 | 35.4 ± 0.2 | 8.9 ± 0.2 | 1.1 |

| 19 | 8 b,e | 150 | 41.8 ± 0.1 | 9.1 ± 0.3 | 1.2 |

| 20 | 8 b,e | 300 | 46.6 ± 0.1 | 8.9 ± 0.1 | 1.3 |

NaCl concentration in a 10-mM PBS buffer;

0.76 μM total [DNA];

Theoretical value;

2.00 μM total [DNA];

Hairpin-like dimer 8 (3:7).

Figure 3.

Experimental and theoretical melting curves for A-T6-B:A′ -T6-B′ (0.76 μM) and the experimental melting curve for A:A′ (0.76 μM) in PBS buffer (10 mM, pH 7.0, 300 mM NaCl). Inset shows the first derivatives of the melting curves.

We also designed a new rSMDH2 7 (3′-A′-5′-T3CT3-5′-B′-3′) to hybridize with rSMDH2 3 (3′-A-5′-T3CT3-3′-B-5′) and form a hairpin-like dimer 8 (3:7). The melting profile of this dimer 8 displays a broader (fwhm = 9.1 ± 0.3 °C, Figure 4) transition compared to rSMDH2 dimer 4 (3:3′) (fwhm = 6.2 ± 0.1 °C). This again supports our hypothesis that ion-cloud sharing is crucial to cooperative melting—the parallel orientation of the DNA duplexes in dimer 4 leads to better overlap between the ion clouds in the two partner duplexes, and sharper melting profile, in comparison to that in dimer 8.

Figure 4.

Melting curves for dimer 8 (3:7; 0.76 μM) and dimer 4 (3:3′; 0.76 μM) in PBS buffer (10 mM, pH 7.0, 150 mM NaCl). Inset shows the first derivatives of the melting curves.

As a control experiment, the melting profiles of the hybrids formed between T6-linked A′-T6-B′ and its complementary sequences A and B (Table 1, entry 5-7) are broader and have lower Tm compared to dimer 6 (Table 1, entry 11-17). As predicted by the neighboring-duplex/effective concentration model,17 when the salt concentration increases, the Tm difference between the A:A′ duplex and the dimer 4 also increases (Table 1, cf entries 1-3 vs 8-10). Similar comparisons hold for dimers 5 and 6.

From the salt-concentration dependence of the melting temperature of the aggregates (Table 1, entries 5-17), the number of cooperative duplexes (Nc, defined in eq S2 in SI) can be calculated for the various SMDH2 hybridization mixtures (see SI).15 As expected for a cooperative dimer pair, Nc for the caged dimers averages between 1.6 and 2.1 ± 0.1. Interestingly, while the Tm's for the control groups A:A′-T6-B′:B and A:rSMDH2-A′-T3CT3-B′:B do not differ significantly from that of A:A′, their Nc's still average in the range 0.9-1.0 ± 0.1, clearly indicating that there is no cooperativity between the duplexes.

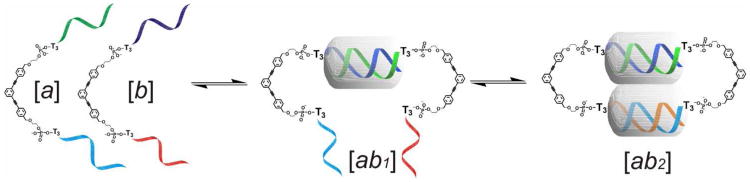

The formation of DNA dimers such as 4-6 from the dissociated DNA partners ([a] and [b]) can be viewed as a three-state event where the first arms come together initially to form [ab1] as a bimolecular reaction (Figure 5). Hybridization of the second arms to give [ab2] is nominally unimolecular, but can be thought of as a bimolecular reaction in which the effective local concentration of the second arms (see SI) is greatly enhanced compared to the solution concentration. For the reverse (melting) process, the first step ([ab2] → [ab1]) is therefore entropically disfavored, but the second step ([ab1] → [a] + [b]) is strongly favored. Additional factors that favor cooperative melting arise as a result of counterion clouds which are shared between the two duplexes in [ab2], but not in later stages, and can be readily modeled by CGMD simulations.14

Figure 5.

A schematic presentation of the hybridization of rSMDH2:rSMDH2 dimer showing three possible states.

Based on the aforementioned effective concentration model and adjusted thermodynamic parameters from CGMD simulations (see SI), analytical melting curves can be generated for dimer 6 (fwhm = 4.7 °C, Figure 3) that closely mimic the experimental melting profiles and Tm increases. This close agreement suggests that our entropic attribution for the melting of SMDH2 materials is a reasonable one: while the first dehybridization is entropically disfavored in comparison to the melting of free DNA duplexes in solution, the second step, where most of the entropy is released is strongly favored, is primarily responsible for the sharp melting behavior in a cooperative, cascade melting mechanism.

In conclusion, we have experimentally demonstrated for the first time that aggregates with two parallel DNA duplexes in close proximity can interact cooperatively, consistent with the prediction by the neighboring-duplex/effective concentration model.14,15 With the help of coarse grain molecular dynamics simulations, we can now begin to construct accurate analytical models that allow us to understand the thermodynamic parameters governing the cooperative interactions that occur when DNA duplexes aggregate. This knowledge will enable researchers to design better DNA-hybrid materials for a wide range of applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Brian Stepp and Erbay Yigit for their help with the DNA melting and PAGE-gel experiments. Financial support for this work was provided by the NSF (Grant EEC-0647560 through the NSEC program) and the NIH (NCI 1U54CA119341-01 through the CCNE program).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Synthetic procedures and characterization data for rigid small molecule-DNA hybrids; methods and data for hybridization experiments; theoretical equations for the analytical model. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Fischler M, Simon U. J Mater Chem. 2009;19:1518–1523. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang KM, Tang ZW, Yang CYJ, Kim YM, Fang XH, Li W, Wu YR, Medley CD, Cao ZH, Li J, Colon P, Lin H, Tan WH. Angew Chem Inter Ed. 2009;48:856–870. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dupraz CJF, Nickels P, Beierlein U, Huynh WU, Simmel FC. Superlattices Microstruct. 2003;33:369–379. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckardt LH, Naumann K, Pankau WM, Rein M, Schweitzer M, Windhab N, von Kiedrowski G. Nature. 2002;420:286–286. doi: 10.1038/420286a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Summerer D, Marx A. Angew Chem Inter Ed. 2002;41:89–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu J, Tan GJ. J Comput Theor Nanosci. 2007;4:1219–1230. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ezziane Z. Nanotechnology. 2006;17:R27–R39. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Condon A. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:565–575. doi: 10.1038/nrg1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho A. Science. 2000;288:1152–3. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5469.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ouyang Q, Kaplan PD, Liu SM, Libchaber A. Science. 1997;278:446–449. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pool R. Science. 1995;268:498–499. doi: 10.1126/science.7725093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taton TA, Mucic RC, Mirkin CA, Letsinger RL. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:6305–6306. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibbs JM, Park SJ, Anderson DR, Watson KJ, Mirkin CA, Nguyen ST. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1170–1178. doi: 10.1021/ja046931i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prytkova TR, Eryazici I, Stepp B, Nguyen SB, Schatz GC. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:2627–34. doi: 10.1021/jp910395k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin RC, Wu GS, Li Z, Mirkin CA, Schatz GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:1643–1654. doi: 10.1021/ja021096v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kudlay A, Gibbs JM, Schatz GC, Nguyen ST, De la Cruz MO. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:1610–1619. doi: 10.1021/jp0664667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long H, Kudlay A, Schatz GC. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:2918–2926. doi: 10.1021/jp0556815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stepp BR, Gibbs-Davis JM, Koh DLF, Nguyen ST. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9628–9629. doi: 10.1021/ja801572n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jessen CH, Pedersen EB. Helv Chim Acta. 2004;87:2465–2471. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.