Abstract

Most of our understanding of G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR) activation has been focused on the direct interaction between diffusible ligands and their seven-transmembrane domains. However, a number of these receptors depend on their extracellular N-terminal domain for ligand recognition and activation. To dissect the molecular interactions underlying both modes of activation at a single receptor, we used the unique properties of the melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R), a GPCR that shows constitutive activity maintained by its N-terminal domain and is physiologically activated by the peptide α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (αMSH). We find that activation by the N-terminal domain and αMSH relies on different key residues in the transmembrane region. We also demonstrate that agouti-related protein, a physiological antagonist of MC4R, acts as an inverse agonist by inhibiting N terminus–mediated activation, leading to the speculation that a number of constitutively active orphan GPCRs could have physiological inverse agonists as sole regulators.

GPCRs are characterized by a transmembrane core of seven α-helices (TM1 to TM7) connected by extracellular and cytoplasmic loops and an extracellular N-terminal domain. This superfamily is divided into different subgroups on the basis of phylogenetic criteria and conserved residues within the helices and also according to the size and characteristics of the N-terminal domain of its members, which has an essential role in the activation of most classes of GPCRs (Supplementary Results, Supplementary Fig. 1). For instance, class B secretin receptors have a conserved N-terminal cysteine network that stabilizes their structure, the alteration of which impairs ligand interactions. Similarly, the N-terminal domain of class B adhesion receptors has a diverse variety of N-terminal domain motifs that determine ligand specificity. Class C glutamate receptors have a conserved N-terminal Venus flytrap domain, and Frizzled/Smoothened receptors have N-terminal Wnt-binding domains that regulate ligand binding and receptor activation1–3. In class A rhodopsin–like receptors, the largest family of GPCRs, the N-terminal domain is important for activation of protease-activated receptors (PARs), which is dependent on proteolytic cleavage and unmasking of an N-terminal domain that acts as a tethered ligand4, as well as for the activation of glycoprotein hormone receptors (GpHRs)5.

Despite this recognized role of the N-terminal domain in GPCR activation, only a limited number of studies have attempted to understand the functional molecular interactions between this domain and the core of the receptor. This is due to the historic emphasis on rhodopsin, the prototypical class A GPCR whose ligand is covalently linked to the core of the receptor, and on GPCRs activated by high-affinity diffusible pharmacological ligands that interact directly with transmembrane helices (for example, adrenergic receptors).

Here we define and compare the relative molecular interactions underlying activation by the N-terminal domain and a high-affinity physiological agonist at a single receptor, the MC4R6. MC4R is one of five melanocortin receptors, a subfamily of the α group of class A Gs protein–coupled receptors6. MC4R is expressed in the central nervous system and is essential for the maintenance of long-term energy balance in humans. Heterozygous mutations in MC4R are the most common genetic cause of severe human obesity, and over 80 naturally occurring pathogenic mutations in this receptor have been described7. A number of studies have mapped the interaction of the endogenous physiological agonist of MC4R, αMSH, to acidic amino acids in TM2 and TM3 of the receptor. In addition to activity induced by this high-affinity ligand, MC4R also shows constitutive activity, as observed by the receptor expression–dependent G protein signaling in cell culture systems8. A basal, agonist-independent, G protein–coupling activity is a common characteristic of many GPCRs and is generally associated with the intrinsic ability of the transmembrane domain of the receptor to undergo a spontaneous conformational transition from the inactive to the active state (or states) in the absence of a ligand9. In contrast with this classical view of constitutive GPCR activity, we have previously shown that, at the MC4R, the constitutive activity is largely established by the agonistic effect of its own N-terminal domain and that this constitutive activity is physiologically relevant8,10,11. In addition, MC4R and two other members of the melanocortin receptor subfamily are also the only known GPCRs to physiologically respond to an endogenous antagonist12–15. Agouti-related protein (AgRP), which is released by an independent population of neurons, inhibits αMSH activation of MC4R. However, unlike neutral antagonists that do not show phenotypic behavior in the absence of a competitive ligand16,17, AgRP also acts as an inverse agonist as it has negative efficacy on the constitutive activity of MC4R14,15.

Using a peptide mimetic of the MC4R N-terminal domain as a pharmacological agent, we find here that the inverse agonism by the endogenous ligand AgRP at this receptor can be attributed in large part to its specific inhibition of the N terminus–induced self-activation. Comparing the activation of the receptor by its N-terminal domain and by αMSH through systematic alanine-scanning mutagenesis, we found that the signaling promoted by these agonists occurs through distinct molecular mechanisms. Notably, the N-terminal domain activates the receptor through a set of amino acids that is crucial for a conserved mode of activation among class A GPCRs, leading to the speculation that inverse agonism may be the original mechanism for modulation of the activity of this receptor.

RESULTS

N-terminal domain of MC4R can act as a diffusible agonist

We had previously demonstrated that the N-terminal domain of MC4R is a tethered ligand and is essential for the overall maintenance of the receptor’s constitutive activity8. Specifically, a receptor lacking the first 24 N-terminal amino acids (MC4R Δ1–24; Supplementary Fig. 2) responds normally to a panel of agonists and to AgRP antagonism of αMSH (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1) but has a low constitutive activity that can be rescued by coexpression of the MC4R N-terminal domain chimerically linked to the transmembrane domain of cluster of differentiation 8 (CD-8) (ref. 8).

Receptor titration experiments demonstrate that this N-terminal domain–dependent constitutive activity of MC4R Δ1–24 represents over 80% of the total MC4R constitutive activity (Supplementary Fig. 3a,b). The activation of MC4R by its N-terminal domain resembles that of PAR1, but the latter requires unmasking of the active site through proteolytic cleavage by thrombin4. In the case of PAR1, it had also been shown that, in the absence of thrombin, exogenous addition of a synthetic peptide mimicking the unmasked active N-terminal domain leads to the activation of the receptor4. Therefore, we tested whether a peptide mimicking amino acids 2–26 of the MC4R (MC4R 2–26; Supplementary Methods) could act as a partial agonist for MC4R Δ1–24. The receptor activity was measured in receptor-transfected HEK293 cells using a luciferase reporter system. Indeed, at 100 μM, MC4R 2–26 but not MC4R 20–39 increased the activity of MC4R Δ1–24 to the level of the constitutive activity of wild-type MC4R (Fig. 1a). The low potency of the N-terminal domain activation (half-maximum effective concentration (EC50) = 72 μM; Supplementary Fig. 4a) is compatible with the high local concentration in the tethered form and is similar to that observed in the case of PAR1 (ref. 4).

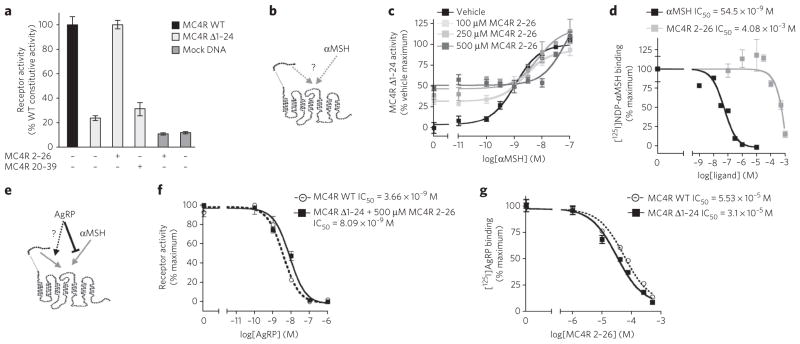

Figure 1. Functional properties of MC4R 2–26.

(a) The full sequence of residues 2–39 corresponding to the N-terminal domain of MC4R has been synthesized as two peptides: residues 2–26 (MC4R 2–26) and residues 20–39 (MC4R 20–39). MC4R Δ1–24 was stimulated by either peptide. Cells transfected with the plasmid pcDNA3.1 encoding LacZ (mock DNA) were used to control for nonspecific activation. WT, wild type. (b) Tested model of interaction of MC4R with the N-terminal domain and αMSH. (c) Dose response curve of MC4R Δ1–24 activation by αMSH in the presence of vehicle (BSA; EC50 = 1.1 nM) versus 100 μM (EC50 = 2.4 nM), 250 μM (EC50 = 7.0 nM) or 500 μM (EC50 = 74.5 nM) MC4R 2–26. (d) αMSH and MC4R 2–26 binding to MC4R Δ1–24. [125I]NDP-αMSH was used as the competitive radio-labeled ligand. (e) Tested model of AgRP interaction with the N-terminal domain. (f) AgRP antagonism of MC4R 2–26 activation of MC4R Δ1–24 compared to AgRP inverse agonism of wild-type MC4R. (g) MC4R 2–26 binding to MC4R Δ1–24 and wild-type MC4R. [125I]AgRP was used as the competitive radio-labeled ligand. Receptor activity is normalized to membrane expression for each receptor. Error bars represent s.e.m. for experiments performed in triplicate.

Indeed, in the presence of 100 μM MC4R 2–26, activation of MC4R Δ1–24 by αMSH mimics that of the wild-type MC4R (Fig. 1b,c and Supplementary Fig. 4b). At higher concentrations, as expected for a partial agonist, MC4R 2–26 lowered the potency of αMSH at MC4R Δ1–24 (Fig. 1b,c and Supplementary Fig. 4c). Finally, MC4R 2–26 displaces radiolabeled NDP-αMSH from MC4R Δ1–24 (Fig. 1d), suggesting that the N-terminal domain of MC4R and αMSH have overlapping binding sites.

AgRP antagonizes the diffusible N-terminal domain

AgRP is of sufficient size and molecular weight to cover the MC4R extracellular binding pocket, acting as an inverse agonist of the MC4R14,15,18. In addition, AgRP inhibits αMSH-induced receptor activation independent of the absence or presence of the N-terminal domain (Supplementary Fig. 3e). The availability of an active diffusible N-terminal peptide allowed us to test whether the inverse agonist activity of AgRP could be attributed to the antagonism of the N-terminal domain (Fig. 1e). AgRP inhibits the activation of MC4R Δ1–24 by MC4R 2–26 with similar potency as its inverse agonism of the wild-type receptor (Fig. 1f). It is notable that AgRP also inhibits the residual N terminal–independent constitutive activity of MC4R Δ1–24 (Supplementary Fig. 3a). In addition, MC4R 2–26 displaced radiolabeled AgRP, with similar affinities for wild-type and Δ1–24 MC4R (Fig. 1g). Together, these data indicate that the inverse agonist activity of AgRP on the MC4R can be attributed mainly to the inhibition of the N terminal–mediated activation of the receptor.

MC4R 2–26 activation does not mimic αMSH activation

Three acidic residues in the second and third transmembrane domains of melanocortin receptors (Glu1002.60, Asp1223.25 and Asp1263.29 in MC4R; superscripts are the generic numbering scheme of Ballesteros and Weinstein, which allows direct comparison among residues in the seven-transmembrane segments of different receptors19; Supplementary Fig. 2) are essential for their activation by melanocortins. Alanine substitution of these residues impairs αMSH binding and activation but does not prevent constitutive activity of the MC4R8 (Supplementary Fig. 5a). We tested whether these mutations also affected activation by the N-terminal domain. When introduced into MC4R Δ1–24, the E1002.60A, D1223.25A and D1263.29A mutations impaired activation of the truncated receptor by αMSH but not by MC4R 2–26 (Supplementary Fig. 5b), demon strating that these three residues are not implicated in receptor activation by the N-terminal domain.

HLWNRS is the minimal N-terminal activating sequence

To outline the molecular interactions underlying the N-terminal activation of MC4R, we first delineated the minimal activating region of the N-terminal domain. We tested a range of smaller overlapping peptides spanning this domain for their efficacy at MC4R Δ1–24 (Supplementary Methods). Although MC4R 2–26 showed the greatest activity, some of its segments failed to activate MC4R Δ1–24 (Fig. 2a). All activating peptides shared the common sequence 14 HLWNRS19 (MC4R 14–19). Notably, this minimal activating sequence encompasses the most conserved portion of the N-terminal region throughout several species (Supplementary Fig. 6) and includes Arg18, a previously described genetic ‘hot spot’ for obesity-causing mutations in the MC4R8,20. In addition, a monoclonal antibody targeting the overlapping MC4R 11–25 region in rats has been reported to function as an inverse agonist in vitro and lead to increased food intake and body weight in vivo11.

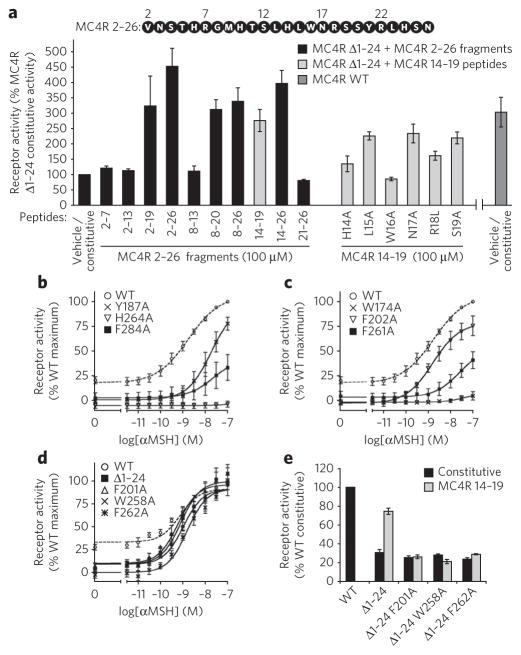

Figure 2. Essential residues in the maintenance of N terminus–mediated receptor activation.

(a) Minimal activating sequence and essential amino acids required for MC4R 2–26 efficacy. MC4R 2–26 peptide sequence is shown at the top of the figure. The stimulations of MC4R Δ1–24 by MC4R 2–19, 2–26, 8–20, 8–26, 14–19, 14–26, 14–19 L15A, 14–19 N17A and 14–19 S19A are not significantly different from the constitutive activity of wild-type MC4R (P > 0.05). Receptor activity is normalized to membrane expression for MC4R Δ1–24 and wild-type MC4R. Error bars represent s.e.m. for experiments performed in triplicate. (b,c) Activation profiles of Y187A, H264A and F284A (b) and W174A, F202A and F261A (c) mutants with low constitutive activity and impaired αMSH response. (d) Activation profiles for F201A, W258A and F262A mutants with low constitutive activity and wild-type–like αMSH response. (e) Activation of MC4R Δ1–24 mutants by the MC4R 14–19 peptide. Receptor activity is normalized to membrane expression for MC4R Δ1–24 and wild-type MC4R. Error bars represent s.e.m. for experiments performed in triplicate.

We further determined the relative role of specific amino acids within this minimal activating sequence. Further truncation of the hexapeptide resulted in complete loss of activation (Supplementary Fig. 7), and H14A, W16A or R18L substitutions markedly disrupted MC4R 14–19 efficacy (Fig. 2a).

TM residues involved in N terminus–mediated activation

To search for potential candidate amino acids interacting with the N-terminal domain, we first surveyed naturally occurring obesity-causing mutations for decreased constitutive activity with preserved activation of the receptor by αMSH (Supplementary Fig. 2)7,20,21. Out of 71 mutations examined, 8 had resulted in decreased constitutive activity and a conserved response to αMSH. Five of these mutations were in the N-terminal domain of the receptor (R7H, R18H, R18C, R18L and T11A)8,20. Three were in the intracellular domains of the receptor (V952.55I, A1543.57D and G231S)20. None were located in the extracellular portions of transmembrane domains or the extracellular loops that would be accessible to the N-terminal domain for interactions.

Considering that His14, Trp16 and Arg18 are the most mutation-sensitive residues of the N-terminal domain (Fig. 2a), we systematically screened all 22 charged and/or aromatic residues that could be accessible for N-terminal domain interaction (Supplementary Fig. 2) for their role in the activation of the receptor by alanine-scanning mutagenesis.

None of the five acidic residue substitutions decreased the constitutive activity of the receptor (Supplementary Fig. 8a). In contrast, substitution of one out of two basic (His2646.54) and eight other aromatic (Trp1744.50, Tyr187, Phe2015.47, Phe2025.48, Trp2586.48, Phe2616.51, Phe2626.52 and Phe2847.35) residues with alanine led to significantly (P < 0.05) reduced constitutive activity compared to the wild-type receptor (Supplementary Fig. 8b,c). From these nine mutant receptors, six (carrying mutations W1744.50A, Y187A, F2025.48A, F2616.51A, H2646.54A or F2847.35A) had considerably altered responses to αMSH (Fig. 2b,c). Three mutant receptors (carrying mutations F2015.47A, W2586.48A or F2626.52A) showed a normal response to the agonist αMSH, a functional profile similar to that of MC4R Δ1–24, consistent with the possibility that these three residues are involved in the activation of the receptor by its N-terminal domain (Fig. 2d). When introduced into MC4R Δ1–24, mutations of the residues Phe2015.47, Trp2586.48 and Phe2626.52 to alanine impaired activation of the receptors by exogenously added N-terminal peptide, confirming their specific involvement in the partial agonism of the N-terminal domain of the receptor (Fig. 2e).

Models of MC4R in complex with the N terminus or αMSH

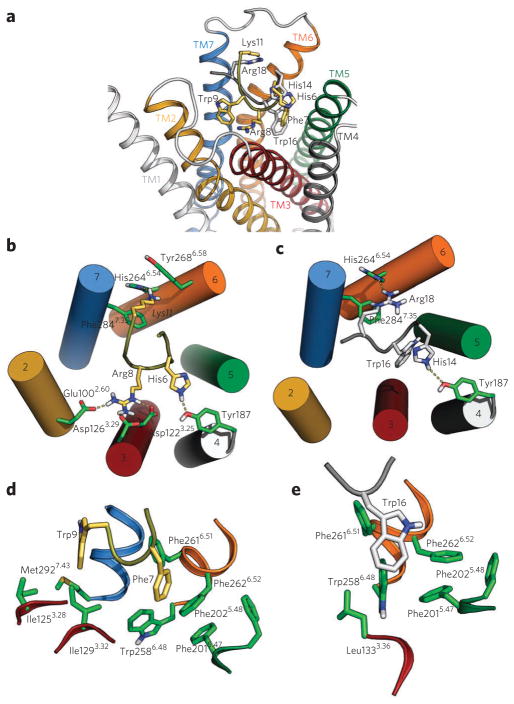

To provide a structural framework for the interpretation of the experimental data, we developed molecular models of the receptor–peptide complexes on the basis of the crystal structures of the β2-adrenergic receptor and of the CXCR4 receptor in complex with a peptide (Supplementary Methods). Figure 3a compares the computationally obtained molecular models of the HLWNRS hexapeptide of the N-terminal domain of MC4R and the 4 MEHFRWGK11 octapeptide from the core of αMSH, in a complex with a molecular model of MC4R. Both peptides are in the main binding site crevice located between the extracellular segments of TMs 3–7. In these models, Arg8 of αMSH forms a network of ionic interactions with Glu1002.60, Asp1223.25 and Asp1263.29 (Fig. 3b), in agreement with previous proposals22 and our experimental results (Supplementary Fig. 5a), whereas the N-terminal hexapeptide (Fig. 3c) does not form these interactions, in agreement with what was suggested by our experimental results (Supplementary Fig. 5b). This putative additional network of ionic interactions is supported by the higher affinity of αMSH for the receptor. In addition, these models also provide a viable rational explanation to the experimentally determined involvement of Tyr187 at the extracellular end of TM4, His2646.54 in TM6 and Phe2847.35 in TM7 (Supplementary Fig. 8b,c) in receptor activation by both the N-terminal hexapeptide (via His14 and Arg18; Fig. 3c) and αMSH (via His6 and Lys11; Fig. 3b) by proposing putative direct interactions between these side chains. Our model suggests that the shorter Phe7 side chain of αMSH cannot interact with Trp2586.48 and the associated Phe2015.47-Trp2586.48-Phe2626.52 aromatic cluster (Fig. 3d). Accordingly, alanine substitutions of these amino acids do not impair αMSH receptor activation (Fig. 2d). In contrast, the proposed mode of binding of the N-terminal hexapeptide to MC4R positions the key Trp16 deep inside the receptor bundle, where it interacts with the highly conserved Trp2586.48 (Fig. 3e). Trp2586.48, together with Phe2015.47 in TM5 and Phe2616.51 and Phe2626.52 in TM6, form a previously reported aromatic cluster involved in the activation of some GPCRs23–25. This provides a possible explanation for the decreased constitutive activity of receptors with alanine substitutions at Trp16 (Fig. 2a), Phe2015.47, Trp2586.48, Phe2616.51 or Phe2626.52 (Fig. 2c–e and Supplementary Fig. 8c). In addition, in our model, Phe2025.48 is also part of this aromatic cluster, in line with the decreased constitutive activity of the F2025.48 A mutant (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 8c).

Figure 3. Models of MC4R in complex with the N terminus or αMSH.

(a) Comparison of the binding modes of the HLWNRS hexapeptide of the N-terminal domain (gray; His14, Trp16 and Arg18 are shown) and the central portion of αMSH (yellow; His6, Phe7, Arg8, Trp9 and Lys11 are shown) to the β2-adrenergic receptor–based model of MC4R. (b,c) View of the complexes between αMSH (b) or the N-terminal hexapeptide (c) and MC4R. Numbered cylinders in b and c represent TMs. (d,e) Detailed view of the complexes between αMSH (d) or the N-terminal hexapeptide (e) and the Phe2015.47-Trp2586.48-Phe2626.52 aromatic cluster of MC4R. The side chains of the N-terminal HLWNRS hexapeptide of MC4R are shown in white, the central portion of αMSH (Supplementary Methods) is shown in yellow, and the side chains of the β2-adrenergic receptor–based model of MC4R are shown in green.

The recently obtained crystal structures of agonist-bound, active conformations of several GPCRs might help to explain this different process of MC4R activation by the N-terminal domain and αMSH. The structures of metarhodopsin II26, the constitutively active rhodopsin27 and the A2A adenosine receptor in complex with the agonist UK-432097 (ref. 28) have shown that Trp6.48 moves toward TM5 relative to the inactive structures, facilitating the rotation and tilt of the intracellular part of TM6. Thus, we hypothesize that Trp16 of the N-terminal domain of MC4R triggers and stabilizes this shift of Trp2586.48 in a similar manner. In contrast, the structures of β1-adrenergic29 and β2-adrenergic30,31 receptors bound to agonists do not contain this shift of Trp6.48. In these cases, the major difference between the binding of full agonists compared to partial agonists or antagonists is the hydrogen bond between full agonists and Ser5.46 in TM5. This illustrates that different mechanisms of signal propagation exist among GPCRs and, as a corollary, that different ligands might also trigger different activation mechanisms at one receptor, as shown here for the receptor N-terminal domain and αMSH.

DISCUSSION

Historically, class A GPCRs have been identified and studied on the basis of their ability to be activated by specific high-affinity diffusible pharmacological ligands interacting directly with the core transmembrane region of the receptor. Notable exceptions include PARs and GpHRs (Supplementary Fig. 1). For PARs, activation of the receptor is dependent on proteolytic cleavage and unmasking of an N-terminal domain that acts as a tethered ligand4. For GpHRs, binding of the glycoprotein hormone to the N-terminal domain leads to receptor activation. Notably, the N-terminal domain of GpHRs arose from a gene fusion event that linked a leucine-rich repeat domain to a GPCR sequence. In the absence of the hormone, the N-terminal domain is inhibitory, and its removal leads to increased activation of the receptor5. Here we find that antagonism by a physiological ligand is a third mode of modulation of an activating N-terminal domain (Supplementary Fig. 1). Activation by the N-terminal domain of MC4R requires the conserved Phe2015.47-Trp2586.48-Phe2626.52 aromatic cluster (the so-called ‘toggle switch’32,33) that is found in most class A GPCRs, where it is mandatory for activation by the various cognate agonists. Remarkably, these key residues are not necessary for receptor activation by the endogenous diffusible agonist αMSH, suggesting that hormone-induced activation might have arisen second in the evolution of the MC4R, which would therefore represent an intermediate situation between N terminus–dependent GPCRs and receptors activated solely by soluble agonists. One can speculate that the latter may have lost N-terminal activation after preferential adaptation to their endogenous ligand, whether it is diffusible as in the β2-adrenergic receptor or covalently bound as in rhodopsin (Supplementary Fig. 1). One can also speculate that such evolutionary separation between receptors activated by soluble and tethered agonists occurred very early in the evolution of class A GPCRs. According to this hypothetical scenario, most current receptor families have evolved to exclusively rely on diffusible agonists, whereas the receptors activated by their N terminus have evolved separately, with some members eventually developing activation by diffusible ligands.

The finding that modulation of MC4R activity by its physiological inverse agonist is independent of the modulation by its endogenous diffusible agonist also suggests that inverse agonism could be the sole mode of activity modulation for some GPCRs (Supplementary Fig. 1, dotted arrow). Indeed, from nearly 400 GPCRs identified within the human genome on the basis of sequence homology, more than 30% are yet to be associated with a physiological ligand34. In addition, although most GPCRs have constitutive activity9, a number of these orphan GPCRs have a high level of such activity35. This high constitutive activity, observed after expression ex vivo in hetero logous cell systems, is compatible with physiological modulation by an inverse agonist in vivo and could provide an explanation for the failure to find a physiological ligand using high-throughput reverse pharmacology assays, mostly limited to the detection of agonism. The use of GPCR constitutive activity and the detection of its inhibition by inverse agonism has been proposed as a new approach to GPCR drug discovery and as a tool to study constitutively active orphan GPCRs36,37. Notably, GPR61 is a recent example of an orphan GPCR with a high constitutive activity mediated by the agonistic effect of its own N-terminal domain38.

Systematically testing whether agonism of the N-terminal domain is essential for the constitutive activity of orphan GPCRs could be a first step in the design of assays aiming at finding physiological ligands for these receptors.

METHODS

MC4R plasmid constructs

Genes encoding wild-type and E42K human MC4R were cloned from genomic DNA into the vector pcDNA 3.1 as previously described39. MC4R Δ1–24 was made as described, and the prolactin signal peptide and a Flag epitope tag (DYKDDDD) were added to both the wild-type MC4R and MC4R Δ1–24 for identical membrane localization8.

Ligand binding assay

Ligand binding was carried out as previously described40. Briefly, HEK293 cells were stably transfected with wild-type or mutant MC4R. Competitive binding was measured as a function of radiolabeled MC4R ligand displacement ([125I]NDP-αMSH, [125I]AgRP; PerkinElmer) in the presence of increasing concentrations of a competitive ligand. Gamma counter readings were normalized for nonspecific binding and plotted as a percentage of maximum radioligand binding.

MC4R activity

MC4R activity was measured as previously described39,40. Briefly, cAMP accumulation was measured in HEK293 cells stably expressing or transiently transfected to express a firefly luciferase reporter driven by a cyclic AMP–responsive element. Cells were transiently transfected with wild-type or mutant MC4R plasmid and a Renilla luciferase plasmid. After stimulation with a choice of ligand, luciferase activity was measured using the Steady-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega) and a microplate luminescence counter (Packard Instrument). Firefly luciferase activity upon MC4R activation was normalized over the transfection efficiency by dividing the firefly luciferase activity by the Renilla luciferase activity. The results were normalized to the corresponding membrane expression for each receptor as determined by a complementary assay (Methods, MC4R membrane expression). The data are represented as percentages in the figures and in the Supplementary Results.

MC4R membrane expression

MC4R membrane expression was measured by ELISA as previously described8. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with N-terminally Flag-tagged MC4R constructs. Cells were fixed with 4% (v/v) paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min at 4 °C following 48 h of transfection. After three washes with PBS, cells were incubated with 1 μg ml−1 M2 Flag-specific antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no: F1804, 1:1,000) for 2 h at 20 °C. Cells were then washed three times with PBS and incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat mouse-specific antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, cat. no: sc-2005, 1:3,000) for 1 h at 20 °C. Following three washes with PBS, 2,2-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the cells, and the attenuance at 405 nm was measured by a spectrophotometer.

Peptide synthesis and MC4R ligands

Peptide synthesis and commercially available MC4R ligands are described in detail in the Supplementary Methods.

Molecular modeling

Generation of the MC4R model in complex with its N-terminal hexapeptide and αMSH are described in detail in the Supplementary Methods section.

For the competitive ligand binding assay, best-fit estimates of the half-maximum inhibitory concentration (IC50) and its 95% confidence intervals were obtained by nonlinear regression fitting of the one-site competition curves using GraphPad Prism 4. For MC4R activity dose-response curves, best-fit estimates of the EC50, IC50 and their 95% confidence intervals were obtained by nonlinear regression fitting of the sigmoidal dose response (variable slope) curves using GraphPad Prism 4. The statistical significance of constitutive activity between the wild-type and mutant receptors was determined using one-way analysis of variance plus a posteriori one-sided Dunnett’s t-test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant DK60540 and an American Heart Association Established Investigator Award to C.V., NIH DK064265 to G.M., an American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship and NIH National Research Service Award Endocrinology Training Grant to B.A.E. and a Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation Award (SAF2010-22198-C02-02) to L.P. C.G. is funded as a Chercheur Qualifié by the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique. We would like to thank H. Bourne, B. Conklin and G. Vassart for reviewing the initial version of the manuscript and providing insightful comments.

Footnotes

Author contributions

B.A.E. contributed to the hypothesis, designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. L.P. designed and performed computational experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. S.Z. performed experiments. D.A.T. contributed to the hypothesis, and designed and performed experiments. G.M. contributed to the hypothesis, and provided reagents and expertise. C.G. contributed to the hypothesis, designed experiments and wrote the manuscript, and C.V. contributed to the hypothesis, directed the work, designed experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper. Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://www.nature.com/reprints/index.html.

References

- 1.Kristiansen K. Molecular mechanisms of ligand binding, signaling, and regulation within the superfamily of G-protein–coupled receptors: molecular modeling and mutagenesis approaches to receptor structure and function. Pharmacol Ther. 2004;103:21–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kobilka BK. G protein–coupled receptor structure and activation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:794–807. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lagerström MC, Schiöth HB. Structural diversity of G protein–coupled receptors and significance for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:339–357. doi: 10.1038/nrd2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scarborough RM, et al. Tethered ligand agonist peptides. Structural requirements for thrombin receptor activation reveal mechanism of proteolytic unmasking of agonist function. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13146–13149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vassart G, Pardo L, Costagliola S. A molecular dissection of the glycoprotein hormone receptors. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breit A, et al. Alternative G protein coupling and biased agonism: new insights into melanocortin-4 receptor signalling. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;331:232–240. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bromberg Y, Overton J, Vaisse C, Leibel RL, Rost B. In silico mutagenesis: a case study of the melanocortin 4 receptor. FASEB J. 2009;23:3059–3069. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-127530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srinivasan S, et al. Constitutive activity of the melanocortin-4 receptor is maintained by its N-terminal domain and plays a role in energy homeostasis in humans. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1158–1164. doi: 10.1172/JCI21927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seifert R, Wenzel-Seifert K. Constitutive activity of G-protein–coupled receptors: cause of disease and common property of wild-type receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2002;366:381–416. doi: 10.1007/s00210-002-0588-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tolle V, Low MJ. In vivo evidence for inverse agonism of Agouti-related peptide in the central nervous system of proopiomelanocortin-deficient mice. Diabetes. 2008;57:86–94. doi: 10.2337/db07-0733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peter JC, et al. Antibodies against the melanocortin-4 receptor act as inverse agonists in vitro and in vivo. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R2151–R2158. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00878.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ollmann MM, et al. Antagonism of central melanocortin receptors in vitro and in vivo by agouti-related protein. Science. 1997;278:135–138. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan W, Boston BA, Kesterson RA, Hruby VJ, Cone RD. Role of melanocortinergic neurons in feeding and the agouti obesity syndrome. Nature. 1997;385:165–168. doi: 10.1038/385165a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nijenhuis WA, Oosterom J, Adan RA. AgRP(83–132) acts as an inverse agonist on the human-melanocortin-4 receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:164–171. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.1.0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chai BX, et al. Inverse agonist activity of agouti and agouti-related protein. Peptides. 2003;24:603–609. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(03)00104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costa T, Herz A. Antagonists with negative intrinsic activity at delta opioid receptors coupled to GTP-binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7321–7325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kenakin T. Efficacy as a vector: the relative prevalence and paucity of inverse agonism. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:2–11. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel MP, et al. Loop-swapped chimeras of the agouti-related protein and the agouti signaling protein identify contacts required for melanocortin 1 receptor selectivity and antagonism. J Mol Biol. 2010;404:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballesteros JA, Weinstein H. Integrated methods for the construction of three-dimensional models and computational probing of structure-function relations in G protein–coupled receptors. Methods Neurosci. 1995;25:366–428. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lubrano-Berthelier C, et al. Melanocortin 4 receptor mutations in a large cohort of severely obese adults: prevalence, functional classification, genotype-phenotype relationship, and lack of association with binge eating. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1811–1818. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calton MA, et al. Association of functionally significant Melanocortin-4 but not Melanocortin-3 receptor mutations with severe adult obesity in a large North American case-control study. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1140–1147. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haskell-Luevano C, Cone RD, Monck EK, Wan YP. Structure activity studies of the melanocortin-4 receptor by in vitro mutagenesis: identification of agouti-related protein (AGRP), melanocortin agonist and synthetic peptide antagonist interaction determinants. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6164–6179. doi: 10.1021/bi010025q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jongejan A, et al. Linking ligand binding to histamine H1 receptor activation. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:98–103. doi: 10.1038/nchembio714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pellissier LP, et al. Conformational toggle switches implicated in basal constitutive and agonist-induced activated states of 5–HT4 receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:982–990. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.053686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holst B, et al. A conserved aromatic lock for the tryptophan rotameric switch in TM-VI of seven-transmembrane receptors. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3973–3985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.064725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choe HW, et al. Crystal structure of metarhodopsin II. Nature. 2011;471:651–655. doi: 10.1038/nature09789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Standfuss J, et al. The structural basis of agonist-induced activation in constitutively active rhodopsin. Nature. 2011;471:656–660. doi: 10.1038/nature09795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu F, et al. Structure of an agonist-bound human A2A adenosine receptor. Science. 2011;332:322–327. doi: 10.1126/science.1202793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warne T, et al. The structural basis for agonist and partial agonist action on a β1-adrenergic receptor. Nature. 2011;469:241–244. doi: 10.1038/nature09746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rasmussen SG, et al. Structure of a nanobody-stabilized active state of the β2 adrenoceptor. Nature. 2011;469:175–180. doi: 10.1038/nature09648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenbaum DM, et al. Structure and function of an irreversible agonist-β2 adrenoceptor complex. Nature. 2011;469:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature09665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi L, et al. β2 adrenergic receptor activation. Modulation of the proline kink in transmembrane 6 by a rotamer toggle switch. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40989–40996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206801200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swaminath G, et al. Probing the 2 adrenoceptor binding site with catechol reveals differences in binding and activation by agonists and partial agonists. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22165–22171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Civelli O. GPCR deorphanizations: the novel, the known and the unexpected transmitters. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bond RA, Ijzerman AP. Recent developments in constitutive receptor activity and inverse agonism, and their potential for GPCR drug discovery. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:92–96. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen G, et al. Use of constitutive G protein–coupled receptor activity for drug discovery. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:125–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Behan DP, Chalmers DT. The use of constitutively active receptors for drug discovery at the G protein–coupled receptor gene pool. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2001;4:548–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toyooka M, Tujii T, Takeda S. The N-terminal domain of GPR61, an orphan G-protein–coupled receptor, is essential for its constitutive activity. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:1329–1333. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lubrano-Berthelier C, et al. Intracellular retention is a common characteristic of childhood obesity–associated MC4R mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:145–153. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaisse C, et al. Melanocortin-4 receptor mutations are a frequent and heterogeneous cause of morbid obesity. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:253–262. doi: 10.1172/JCI9238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.