Abstract

Objectives

To analyse the parental understanding of informed consent information in first-line randomised clinical trials (RCTs) including children with malignant solid tumours and to assess parents’ needs for decision-making.

Design

Observational prospective study.

Setting

3 paediatric oncology centres in the Parisian region in France.

Participants

53 parents were approached to participate in a RCT for their child with malignant solid tumour, over a 1-year period. 40 parents have been interviewed in our study.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Parental understanding of information in RCTs, parents’ needs for decision-making. Parents were questioned by a psychologist, independent of the paediatric oncology teams, using a semidirected interview, 1 (M1) and 6 months (M6) after the consent was sought.

Results

18 parents (45%) did not understand the concept of randomisation. Half of the parents could explain neither the aim of the clinical trial nor the potential benefit to their child of inclusion. 35 parents (87.5%) expressed very few specific risks related to the trial. Being mostly French-speaking (p=0.03) and the reading of the information sheet by the parents (p=0.0025) improved their understanding. The parental comprehension did not differ between M1 and M6. The principal factors underlying their decision were confidence in the medical team (39%), wish to access to the best treatment (37%) and the best quality of life (37%).

Conclusions

Despite medical explanations, parents have limited knowledge in some areas in first-line RCTs and improvements of information process are required. The risks specific to the randomised trial are underestimated by parents and the unproven nature of the treatment is not well-known or understood.

Keywords: Medical Ethics, Medical Law

Article summary.

Article focus

How is the parental comprehension of the benefits/risks to their child with a solid tumour for the inclusion in a randomised phase 3 trial?

Do perceived risks and benefits figure prominently in the parental decision about randomised phase 3 trial participation?

Key messages

Most parents had understood the general aspects, by contrast, less than half the parents had correctly understood the more specific information such as the aims of the study, randomisation, the various phases of treatment and the risks specific to the randomised trial.

Parents tend to underestimate risks specific to the randomised trial, and the unproven nature of the treatment is not well-known or understood.

Quality of life could be a crucial element in the decision of parents to agree to the participation of their child in a randomised phase 3 trial.

Strengths and limitations of this study

We have data that reflect the full spectrum of paediatric oncology clinical research, including children with solid or brain tumours, whereas most of the available paediatric data are related to research for newly diagnosed acute leukaemia.

The parents were asked to participate in this study closely to having consented. Thus, the risk of recall bias was limited.

Introduction

Cancers can occur before the age of 15 years in 1 out of every 500 children and 1700 new cases are recorded each year for this age group in French registries (http://sfce1.sfpediatrie.com/). Although global cure rates in paediatric cancers today achieve 80% in western countries, cancers are still the second leading cause of death in children between 1 and 15 years, after accidents. The optimisation of treatment in paediatric oncology is desirable not only to continue to improve cure rates but also to decrease late effects. In this setting, randomised clinical trials (RCTs) to test new treatment options are essential in paediatric oncology.

The legislation requires that parents give permission for a minor to enroll in a study, and it is important for researchers to increase their understanding of how parents arrive at a decision in this matter.1 2 The balancing of potential risks and benefits could be critical for parental decisions about allowing their children to participate in research studies and understanding how people weigh these factors is a key point. Boccia et al3 suggested that perceived risk and benefit figure prominently in a decision about research. The patients and their parents must, therefore, necessarily receive appropriate information about the possible risks and the uncertain nature of the benefits of participation to allow them to make truly autonomous decisions about participation in trials. They also require adequate information concerning crucial aspects of RCTs if they are to make an informed decision. However, published findings indicate that parents or patients often misunderstand the research to which they consent.4–7 Furthermore, most of the available paediatric data on the information process in the context of phase 3 trials in oncology are related to research for newly diagnosed acute leukaemia8–10; few data are available that reflect the full spectrum of paediatric oncology clinical research, including children with solid or brain tumours.

The primary aim of this study was to analyse parental understanding of oral and written information in RCTs including children with varied solid tumours. The secondary aim was to assess the parents’ statements in order to identify parental needs for decision-making.

Methods

Sample population

This prospective study was carried out in the oncology departments of the three paediatric oncology centres in the Parisian region—Institut Curie (Paris), Institut Gustave Roussy (Villejuif) and Hôpital Armand Trousseau (Paris). This study was approved by the appropriate institutional review board (Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile de France III Hôpital Cochin). The parents from these three centres who had been asked to give consent for the participation of their child in a phase 3 randomised trial were included in this study, over a 1-year period. The doctors provided the parents with a copy of the information and consent forms and a summary diagram of the various phases of the research protocol. To avoid bias owing to the assessment only of patients with a positive attitude to RCTs, we also included the parents of children who had declined to participate in the trial. The characteristics of these randomised phase 3 trial protocols are described in table 1: most were trials aiming to decrease the toxicity of treatment without affecting its efficacy. With the agreement of physicians participating in the study, the physician seeking parental consent suggested for the participation in our study to the parents. Non-inclusion criteria included consent in a language other than French. Families agreeing to participate were seen at the time of a planned consultation during routine follow-up or at the time of a hospital admission in order to minimise the additional constraints (time and travel) imposed on the parents.

Table 1.

Description of the protocols studied according to the information leaflets

| n | Disease | Main objective | Individual benefit | Randomisation | Treatment duration | Specific risks | Alternative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | Retinoblastoma | Conservative treatment, reduction of adverse effects | Conservative treatment, reduction of adverse effects | Standard chemotherapy vs new regimen | 4–6 months | Auditory, renal, consciousness, pains in the limbs and jaw | Standard CT, enucleation |

| 4 | Ewing's sarcoma | R1: reduction of toxicity | Lower renal toxicities | Standard CT vs new regimen | Not specified | Renal, decrease in sperm count/fertility++ | Standard CT |

| R2: evaluation of the efficacy | |||||||

| 7 | High-risk neuroblastoma | Comparison of efficacy and toxicity of two high-dose chemotherapy regimens | Same efficacy, but fewer adverse effects | High-dose CT vs another high-dose CT | Not specified | Hepatic, thyroid, renal, auditory, endocrine, fertility | Standard CT |

| 2 | Low-grade glioma | Evaluation of the efficacy of a new chemotherapy combination | Best possible CT | Standard CT vs the new CT combination | 81 weeks | Secondary induction of leukemia, haematological and infectious toxicity | Standard CT |

| 4 | Standard-risk medulloblastoma | Evaluation of the efficacy of hyperfractionated RT and reduction of toxicity | Best possible RT, lower long term toxicity | Classical RT dose vs hyperfractionation | 16 months | Neuro-cognitive impairment and endocrine problems | Classical fractionation of RT |

| 5 | Localised nephroblastoma | Assessment of the equivalence of two CT regimens | Same efficacy, but fewer adverse effects | Standard CT vs new regimen | 25–30 weeks | Cardiac | Standard CT |

| 1 | Standard-risk hepatoblastoma | Reduction of toxicity | Same efficacy, but fewer adverse effects | Standard CT vs new regimen | 3–5 months | Cardiac | Standard CT |

n, number of children included in this study; CT, chemotherapy; RT, radiotherapy.

Instrument

The parents were seen twice by a qualified psychologist: 1 month (M1) and 6 months (M6), after they were asked to participate in a RCT. These interviews took place on site and were recorded and transcribed in their entirety. The parents were allowed to express themselves freely, in the framework of a semidirected interview, in response to standardised questions. The structure for the semidirected interviews was developed in collaboration with psychologists, the parent of a former patient representing a patients’ association and some of the investigating doctors from the centres participating in this study. This structure has been validated in previous studies.8 11 The interview covered various aspects of informed consent (IC); we evaluated parental comprehension based on the 11 elements included in the information sheet for each protocol. The questions asked to assess parental comprehension are described in table 2.

Table 2.

Questions asked during the interview addressing the level of understanding

| No. | Concept | Question |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Participation in a research protocol | ‘Is your child being treated as part of a research protocol?’ |

| 2 | Aim of the protocol | ‘What is the aim of this protocol?’ |

| 3 | Course of the protocol | ‘What is planned for your child in the framework of this protocol?’ |

| 4 | Principle of randomisation | ‘If you gave consent for a protocol in which two different treatments might be given, do you know how the treatment given to your child was chosen? If yes, how?’ |

| 5 | Individual benefit | ‘What benefits do you expect your child to gain from participation in this protocol?’ |

| 6 | Collective benefit | ‘Could you describe the possible benefits to other children of the participation of your child in this protocol?’ |

| 7 | Risks | ‘What are the possible risks to your child of participating in this protocol?’ |

| 8 | Alternatives | ‘If you had not consented to the participation of your child in this protocol, what care would your child have received?’ |

| 9 | Voluntary nature of participation | ‘Was the participation of your child in this protocol voluntary?’ |

| 10 | Duration of participation | ‘How long were you told that the participation of your child in this protocol would last?’ |

| 11 | Freedom to withdraw from the project at any time | ‘Could you change your mind once the study had begun?’ |

We tried to identify the elements predictive of a good understanding of the information provided at the time at which consent was sought: parental socioprofessional category (high standing/intermediate status/no profession), the principal language spoken, whether the information document was read by the parents (yes/no), personal efforts to find information (yes/no). We used the following questions to determine the reasons for which the parents had given their consent: “How difficult was it to take the decision you took concerning the participation of your child in this protocol?”, “What were the principal elements underlying your decision?”, “Who do you feel took the final decision?” and “What do you expect from the doctor?”.

Data analysis

Each interview was independently coded by two psychologists, with the coding reviewed by a paediatrician in cases of disagreement. Comprehension was classified as ‘complete’, ‘partial’ or ‘null’ for each element if all, some or none of the information sheet was expressed by the parents. When considering risks, only those specific to the randomised trial were considered (table 1). To test the influence of covariates on comprehension, partial and complete comprehension were pooled for each of the 11 elements and compared with the absence of comprehension. We evaluated the influence of the covariates on the percentage of the elements understood by the parents. A mixed effects model taking into account the subject and items as crossed random effects was used to assess the stability of parental comprehension between the two interviews at M1 and M6. The data collected were put into an Access database. The results are expressed as percentages, means and standard deviations, medians and ranges. χ2 tests were carried out to compare qualitative values, t tests were used to compare quantitative values (normality assumption was checked by quantile–quantile plots and Shapiro-Wilks’ test) and logistic regression analyses were carried out to assess the influence of covariates. Agreement between the two psychologists was assessed with a weighted κ reliability test for ordered data.

Results

During our study period, 53 families were approached to participate in a RCT. Forty families have been interviewed in our study. Our recruitment rate was 75%. Thirteen families were non-interviewed for several reasons: the delay of 1 month was exceeded or the physicians have forgotten to propose our study.

We carried out 40 first interviews, including four with parents who declined participation in a randomised phase 3 trial (1 child with medulloblastoma, 1 with hepatoblastoma and 2 with retinoblastoma). We interviewed 37 mothers and 20 fathers (17 couples, 3 men attending alone and 20 women alone). We carried out 32 s interviews: four of the original interviewees (or couples) declined a second interview and four others were lost to follow-up for this study (management continued at another center). We interviewed 25 mothers and 14 fathers (7 couples, 7 men attending alone and 18 women alone). We considered the responses of each of the couples as if they were individuals (ie, below, ‘parent’ refers to the mother, father or couple interviewed). Regarding the values of weighted κ obtained, 0.84 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.90) and 0.93 (95% CI 0.85 to 0.96) for M1 and M6, respectively, there was a high degree of agreement between the two psychologists about the coding of each interview. The characteristics of the study group are summarised in table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of participating parents

| Characteristic | Study group |

|---|---|

| Relationship to child (n, %) | |

| Father | 20 (35) |

| Mother | 37 (65) |

| Marital status (n, %) | |

| Married/living with partner | 37 (92) |

| Divorced/separated | 3 (8) |

| Parents’ profession (n, %) | |

| High standing | 11 (19) |

| Intermediate status | 37 (65) |

| No profession | 9 (16) |

| Mostly French-speaking (n, %) | |

| Yes | 50 (86) |

| No | 7 (14) |

| No. of children (n, %) | |

| 1 | 11 (27.5) |

| 2–3 | 21 (52.5) |

| 4+ | 8 (20) |

| Patients’ age (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 4.23 (4.5) |

| Median | 1.93 |

| Range | 5 months–15 years |

| First interview (n=40, 17 couples) | |

| Duration (minutes, mean (SD)/ median, range) | 51(17.8)/50.0, 20–90 |

| Time since inclusion (days, mean (SD)/median, range) | 34(6.3)/31.5, 23–50 |

| Second interview (n=32, 7 couples) | |

| Duration (minutes, mean (SD)/ median, range) | 34(13.2)/35.0, 15–60 |

| Time since inclusion (months, mean (SD)/median, range) | 8.4(2.8)/8.0, 5–16 |

In 64% of the cases, information about the protocol had been provided by a single doctor, to both parents simultaneously in 91% of these cases. Twenty-seven parents (68%) had reread the information document. When asked if they had looked for information themselves, 13 parents (32.5%) replied in the negative, while others (67.5%) having mostly (24/40) searched for information about the disease rather than about the randomised clinical trial (7/40). Internet was the principal source of information for these parents.

Parental comprehension

At the first interview, six parents (15%) confused consent for care with consent for research. Each of these cases of confusion concerned a different protocol. Thirteen of the parents (34.2%) did not know that randomisation had occurred and five (13.2%) knew that randomisation existed but could not explain it clearly. When asked about the risks specific to the randomised trial, four parents (10%) were unable to cite a single risk, 35 parents (87.5%) were able to cite less than half the risks and one parent (2.5%) was able to cite more than half the risks.

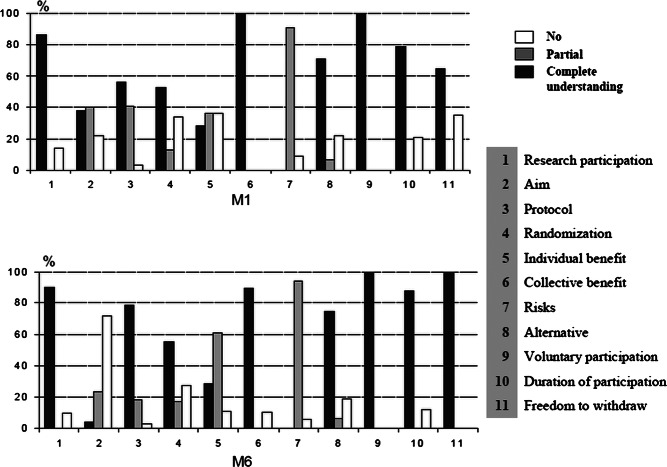

The results of the second interviews were compared with those of the first interview: the level of parental comprehension did not differ markedly between M1 and M6 (p=0.5). Figure 1 summarises the comprehension of the 11 elements described in the methods for the two interviews.

Figure 1.

Percentage of parents who understood each of the 11 items at M1 and M6.

As far as the benefit to their children was concerned, parents giving a different response from that indicated in the information document (first interview, 35% of parents/second interview, 11.1% of parents) expressed other aspects of the benefits anticipated for their child. Some felt there was a benefit in terms of quality of life (less time spent in hospital, fewer displacements), decreasing the amount of time for which their child would not attend school

I think I would have had to stay here all day and he would have had to have two sessions, but he wanted to go to school and that's why he preferred to do it in one go, because the old treatment takes three days and this one only takes one day, so for that reason alone, it's better for him in my opinion.

Other parents had hopes of beneficial effects in terms of their child being cured

Anyway, for him, if it's beneficial he's cured… and that's the most important thing.

Some parents expressed notions of altruism

Their aim and our aim are the same, because their goal is to progress in their studies, to save children…, C. has benefited from what went before and so he should help those who will come after him too.

Finally, some parents agreed to participate because they considered the research protocol to be providing access to better follow-up than they would have obtained with the standard treatment

We were told, relatively clearly, that children who followed research protocols… I'm not saying that the others are neglected… but they are possibly followed a bit more closely than children given the classic treatment, because of the phenomenon of data collection for research.

If we look more closely at the responses of the four parents who refused to allow the participation of their children in a research protocol, they had no notion (0/4) of an expected benefit for their child (Yes but I don't see why it's beneficial for him, because in some ways it's still being evaluated).

Fluency in French (p=0.03) and reading the information notice (p=0.0025) were the only covariates tested that significantly increased parental comprehension (table 4).

Table 4.

Factors predictive of sufficient understanding of the information

| Covariates | Per cent items understood | p |

|---|---|---|

| Parents’ profession | ||

| High standing | 88.7 (SD 13.5) | 0.09 |

| Intermediate status | 86.0 (SD 15.8) | |

| No profession | 72.5 (SD 27.6) | |

| Mostly French-speaking | ||

| Yes | 84.8 (SD 18.7) | 0.03* |

| No | 61.9 (SD 29.6) | |

| Parents read the information sheet | ||

| Yes | 88.7 (SD 14.8) | 0.0025* |

| No | 68.5 (SD 24.6) | |

| Parents sought additional informations | ||

| Yes | 84.5 (SD 18.1) | 0.29 |

| No | 77.2 (SD 25.1) |

Reasons for participation and physician's influence on the decision to participate

When asked how they felt about taking this decision, 24 parents (60%) said that they felt it was ‘a logical decision’ and 10 parents (25%) said that they had found it difficult. The others said that they were not really ‘ready’ to take a decision. In response to the question about the elements guiding the decision, the most frequently given answers were confidence in the medical team (n=15, 39%), access to the best possible treatment for the child (n=14, 37%) and improvements in quality of life (n=14, 37%). Most of the parents (n=34, 85%) said that they had taken the decision together, whereas the others had shared the task of decision-making with the doctor (n=1, 2.5%) or with the child (n=5, 12.5%). The parents expected the following from the doctor: communication (17/22, 77%), sincerity (11/22, 50%), availability (11/22, 50%), humanity (7/22, 32%) and competence (7/22, 32%).

Discussion

Ideally, parents giving consent for inclusion in a randomised clinical trial should have understood all the elements required by law to protect the participant. In reality, parental comprehension is highly variable and depends on the elements considered. Most parents had understood the general aspects such as the potential benefit to other children, the nature of the study (a clinical trial), the notion of voluntary participation, the duration of participation, the alternatives opened to them and the possibility of withdrawal at any time. By contrast, less than half the parents had correctly understood the more specific information such as the aims of the study, randomisation, the various phases of treatment and the risks specific to the randomised trial. These results are similar to published findings.4 5 8 12 For example, for randomisation in our study, some of the parents had views about the best ‘arm’ for their child: some preferred the standard treatment, which they considered to be less risky,13 whereas others were disappointed that their child was in the standard treatment arm because they could not see the point of having consented to participation in the study.14 We wished to focus more specifically on parental comprehension of the potential (or expected) benefits to their child of inclusion in a randomised phase 3 research protocol. Indeed, less than one-third of the parents were able to describe specifically the potential benefits to their child, as stated in the information document. In a recent study, Tait et al15 showed, through the use of scenarios, that only a one-quarter of the parents had fully understood the benefits to their child, and comprehension was even lower for studies of treatments with efficacy levels similar to those of the standard treatment, but lower expected toxicity. In our study, the parents expressed other expectations such as benefits in terms of quality of life (less time spent in hospital, fewer displacements), resulting in fewer hours of absence from school. This aspect of the perception of the benefits anticipated by parents has been identified before in phase I trials in adults.16 17 Other parents had hopes for the cure of their child, not differentiating between the trial and standard management, as described by Caldwell et al18 Finally, some parents agreed to the participation of their child in a phase three randomised trial because they considered that it would provide access to better follow-up than standard treatment as this has also been reported in non-oncological protocols.19–21 In our study, reading the information document improved parental comprehension. Unfortunately, some of these documents are difficult to read,22 23 so it is important for the investigating doctors to pay particular attention when writing such documents, to ensure that they are clear, as short as possible and understandable by all. O'Lonergan et al24 recently reported a novel approach in which visual and audio media (multimedia) were used, rather than a paper-based written text document, to make the information easier to comprehend. However, this was a hypothetical research study involving simple, low-risk procedures and may therefore not be representative of actual research studies.

As shown above, some of the elements of the research protocol were well understood, but not by all the parents. So, how can the parents decide? Although not yet demonstrated in paediatrics to our knowledge, quality of life could be a crucial element in the decision of parents to agree to or refuse the participation of their child in a randomised phase 3 trial. The smaller amount of time spent in hospital and the smaller number of journeys for a research protocol than for standard treatment was an element that appeared frequently in the decision-making process. Recent studies have reported that logistic constraints are a major element in the decisions of adult patients,25 26 sometimes even outweighing benefits. In our study, the parents took into account the benefits and constraints of inclusion to a much greater extent than the risks specific to the research protocol, as indicated by their poor ‘recall’ of the risks. However, there may be several reasons for this recall failure. For example, having given their consent for participation, the parents may minimise the impact of potential risks, focusing instead on the possible benefits of participation. Other parents may try to protect themselves psychologically by blocking out the largest risks. The parents may also feel that their child's illness poses a greater and more immediate threat, in terms of morbidity and mortality, than the risks inherent to a clinical trial. These and the other factors affect people's perceptions of risk, potentially accounting for the poor recall of risks specific to the randomised trial.27 Overall, even if the decision was difficult for some of the parents, more than half felt that it was logical. The decision seemed to be linked to the confidence of the parents in the investigating doctor and their relationship with that doctor.28 This confidence overcame the imbalance in knowledge between the parents and the doctor.8 14 By contrast, a lack of confidence in the doctor may be associated with the decision being more difficult for the parents.11 In previous studies,29–31 the way in which the investigating doctor presented the trial to the patient was found to affect the likelihood of participation. In our study, the parents recognised that the doctor played an important role in their decision, but they did never feel obliged to sign the consent form.

What may appear to the investigating doctor to be a poor understanding of the research protocol may actually correspond to the parents’ construction of the situation to render it acceptable, thus allowing them to fulfill their role as protectors of their children. As suggested by Shilling,28 given that it is difficult to accept that there is uncertainty about the effectiveness of trial treatments and assumptions that the experimental treatment will necessarily be superior, these responses indicate that the parents seek hope and certainty in this uncertain situation in which they feel threatened. Parents need to give their decision some meaning, by seeing it as being in the best interests of their child.

In conclusion, most parents understand most of the elements of IC well. However, knowledge is limited in some areas and improvements of information process are required. Parents tend to underestimate risks specific to the randomised trial and the unproven nature of the treatment is not well known or understood. Investigators should also systematically ask the parents to reformulate the information they have been given to verify that they have understood; this would also encourage active parental participation in a two-way information exchange process.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the parents who agreed to participate in this study, making this work possible. We thank all the investigating doctors from the Société Française des Cancers de l'Enfant (SFCE), the psychologists (Amélie de Haut de Sigy and Anne Charlotte Foubert) and also the clinical research assistants from all centres.

Footnotes

Contributors: HC, DD and FD conceived this study and HC obtained research funding. JMT, NB and HC was in charge of all the data analyses. HC took the lead in reviewing the literature and crosschecking references. HC and JMT drafted major portions of the initial manuscript, whereas DD and FD helped refined it. The other authors CP, JLP, AA and HP were investigators. HC, JMT, NB, DD, FD, VMC, LB and DO have seen and approved the submission of this version of the manuscript and takes full responsibility for the manuscript.

Funding: This work received funding from a clinical research initiation contract (DRRC APHP).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board (Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile de France III Hôpital Cochin).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Loi n°2004-806 du 9 août 2004 sur la recherche biomédicale. Code de la Santé Publique livre 1 titre 2. http://www.legifrance.fr.

- 2.Directive 2001/20/EC of the European parliament and of the council of 4 april 2001 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the member states relating to the implementation of good clinical practice in the conduct of clinical trials on medicinal products for human use. http://europa.eu.int [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boccia ML, Campbell FA, Goldman BD, et al. Differential recall of consent information and parental decisions about enrolling children in research studies. J Gen Psychol 2009;136:91–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kodish E, Eder M, Noll RB, et al. Communication of randomization in childhood leukemia trials. JAMA 2004;291:470–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kupst MJ, Patenaude AF, Walco GA, et al. Clinical trials in pediatric cancer: parental perspectives on informed consent. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2003;25:787–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falagas ME, Korbila IP, Giannopoulou KP, et al. Informed consent: how much and what do patients understand? Am J Surg 2009;198:420–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergenmar M, Molin C, Wilking N, et al. Knowledge and understanding among cancer patients consenting to participate in clinical trials. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:2627–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chappuy H, Baruchel A, Leverger G, et al. Parental comprehension and satisfaction in informed consent in paediatric clinical trials: a prospective study on childhood leukaemia. Arch Dis Child 2010;95:800–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller VA, Drotar D, Burant C, et al. Clinician-parent communication during informed consent for pediatric leukemia trials. J Pediatr Psychol 2005;30:219–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenley RN, Drotar D, Zyzanski SJ, et al. Stability of parental understanding of random assignment in childhood leukemia trials: an empirical examination of informed consent. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:891–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chappuy H, Doz F, Blanche S, et al. Parental consent in paediatric clinical research. Arch Dis Child 2006;91:112–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiley FM, Ruccione K, Moore IM, et al. Parents’ perceptions of randomization in pediatric clinical trials. Children Cancer Group. Cancer Pract 1999;7:248–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snowdon C, Garcia J, Elbourne D. Making sense of randomization; responses of parents of critically ill babies to random allocation of treatment in a clinical trial. Soc Sci Med 1997;45:1337–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eiser C, Davies H, Jenney M, et al. Mothers’ attitudes to the randomized controlled trial (RCT): the case of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) in children. Child Care Health Dev 2005;31:517–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tait AR, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Fagerlin A, et al. Effect of various risk/benefit trade-offs on parents’ understanding of a pediatric research study. Pediatrics 2010;125:e1475–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinfurt KP, Castel LD, Li Y, et al. The correlation between patient characteristics and expectations of benefit from Phase I clinical trials. Cancer 2003;98:166–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng JD, Hitt J, Koczwara B, et al. Impact of quality of life on patient expectations regarding phase I clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:421–8 Erratum in: J Clin Oncol 2000;18: 1807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caldwell PH, Butow PN, Craig JC. Parents’ attitudes to children's participation in randomized controlled trials. J Pediatr 2003;142:554–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pletsch PK, Stevens PE. Inclusion of children in clinical research: lessons learned from mothers of diabetic children. Clin Nurs Res 2001;10:140–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gammelgaard A, Knudsen LE, Bisgaard H. Perceptions of parents on the participation of their infants in clinical research. Arch Dis Child 2006;91:977–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Stuijvenberg M, Suur MH, de Vos S, et al. Informed consent, parental awareness, and reasons for participating in a randomised controlled study. Arch Dis Child 1998;79:120–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ménoni V, Lucas N, Leforestier JF, et al. Readability of the written study information in pediatric research in France. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e18484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ménoni V, Lucas N, Leforestier JF, et al. The readability of information and consent forms in clinical research in France. PLoS ONE 2010;5:e10576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Lonergan TA, Forster-Harwood JE. Novel approach to parental permission and child assent for research: improving comprehension. Pediatrics 2011;127:917–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avis NE, Smith KW, Link CL, et al. Factors associated with participation in breast cancer treatment clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:1860–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cox K, McGarry J. Why patients don't take part in cancer clinical trials: An overview of the literature. Eur J Cancer Care 2003;12:114–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lloyd AJ. The extent of patients’ understanding of the risk of treatments. Qual Health Care 2001;10(Suppl 1):i14–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shilling V, Young B. How do parents experience being asked to enter a child in a randomised controlled trial? BMC Med Ethics 2009;10:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albrecht TL, Ruckdeschel JC, Riddle DL, et al. Communication and consumer decision making about cancer clinical trials. Patient Educ Couns 2003;50:39–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jenkins V, Fallowfield L, Solis-Trapala I, et al. Discussing randomized clinical trials of cancer therapy: Evaluation of a Cancer Research UK training programme. BMJ 2005;330:400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harth SC, Thong YH. Parental perceptions and attitudes about informed consent in clinical research involving children. Soc Sci Med 1995;41:1647–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.