Abstract

Objectives

The aim of the study was to explore and describe the reliability and validity of an instrument to measure preschool children's reactions to and coping with indoor noise at preschools or day care centres.

Design

Data were derived from an acoustical before and after intervention study providing repeated measurements.

Setting

The study was performed at seven preschools in Mölndal, Sweden.

Participants

Children were recruited from these preschools and the final sample comprised 61 and 59 preschool children aged 4–5 years, with a response rate of 98% and 48% girls and 52% boys. Two children were excluded from analysis because they fell outside the age range.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The instrument was developed based on a qualitative study performed in Swedish preschools. Questions pertained to preschool children's perception of noise when at school, their bodily and emotional reactions to it, non-specific symptoms and the coping strategies used by them to diminish the detrimental effects of the noise.

Results

Confirmative factor analysis yielded a three-factor model fitted to 10 items pertaining to angry reactions, symptoms and coping. The model fit was moderate to good (standardised root mean square residual=0.08, 0.12; adjusted goodness of fit=0.97/0.91) in the before and after conditions, respectively. The scales showed moderate to good reliability in terms of internal consistency, with an α ranging between 0.52 and 0.67, and was stronger in the before condition. Concurrent validity was strongest for symptoms by comparing groups based on bodily reaction (general and sound specific).

Conclusions

Young children's emotional and bodily reactions to coping with noise can be reliably measured with this instrument. Like adults and older children, young children are able to distinguish between emotional reactions, bodily reactions, coping and unwell-being. Future research on larger groups of preschool children is needed to further refine the questions, in particular the questions pertaining to well-being.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Public Health

Article summary.

Study focus

Only a few studies have been performed on how noise affects preschool children.

A prerequisite to do so is a method to measure perception, emotional and bodily reaction and coping with noise in the preschool situation.

This study explored the reliability and validity of such an instrument based on data derived from a before after intervention study which was carried out at seven preschools in Sweden.

Key messages

The results show that preschool children can indeed make a clear distinction between perception of and reaction to different types of noise and bodily reactions.

Visual representation of emotional reactions and the location of bodily reactions is a good and reliable way to measure reactions in young children.

More work on larger samples will need to be done to further develop a standard instrument to be used in preschool-aged children.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The strength of this study lies in the fact that the questions posed to the children were based on focus group discussion and worded in their own ‘language’.

A major limitation is the relatively small sample size.

Introduction

Background

Earlier studies show that the sound environment at preschools may be a serious occupational and public health problem. Voss1 measured 8 h equivalent noise exposure levels of 80 dB (LAeq) in day care centres in Denmark. Maxwell and Evans2 report 4 h (LAeq) levels of 76 dB and peak levels of 96 dBC in preschools in the USA. WHO recommends an A-weighted equivalent noise level of 35 dB (LAeq) at preschools in order not to disturb communication.3 Dominant noise sources in preschools are sounds from children's activities. In contrast to elementary schools, the sound environment in preschools is highly intermittent, uncontrollable and characterised by peak levels of high spectrum frequency, originating from voices and children's activities. In order to describe the sound environment, the equivalent noise level (LAeq) is used to represent an average sound pressure level over a given time, while the highest sound pressure levels of the intermittent sounds are better described by their maximum noise levels (LAFmax) or peak levels (LCpeak).

Acoustical improvements in preschools and schools are most often made by fitting walls and ceilings with sound absorption panels. The calculated direct effects are a reduction of the reverberation time—the time it takes for a sound to decay 60 dB from its original intensity—and moderate reduction of the sound level.4 5

Noisy preschool environments could lead to a reduced understanding of speech and, as a consequence, impaired reading and writing abilities.2 Exposures at a young age might also affect other aspects of later life functioning and the development of disease. Effects described in the literature indicating such a mechanism pertain to hearing impairment3 6 and increased levels of cortisol in children attending day care centres.7–9 In preschool children also, an association was found between noise levels at school and observed hoarseness, breathy voice and vocal hyperfunction.10 Studies in older children have confirmed their effects on reading comprehension and memory,11 performance,12 coping, well-being and stress,13 14 and on behaviour and mental health.15

Reactions to coping with environmental noise have been studied extensively in the past 30–40 years for adults.16 Several recent studies have also addressed annoyance and coping in schoolchildren,12 13 17–21 while only a handful of studies have addressed this issue in younger (preschool) children.2 22–24 In comparison with adults, children in general and preschool children in particular may be more susceptible to the effects of noise because they have less capacity to anticipate, understand and cope with stressors20 and because they are in a crucial and sensitive phase of their development.3 11

Instruments to investigate young children's reactions to noise are not available. In order to fill this gap and in preparation of the development of such an instrument, a qualitative study was performed in 2006 among 36 preschool children in Mölndal (Sweden), aged 4–6 years,25 using the constructivist-grounded theory as a qualitative approach.26 The children were asked about their perception of sound in the preschool situation, their understanding of the source and their perceived reactions at the emotional and bodily level. Also, the degree of familiarity and comprehensibility of the sounds, manageability/control as well as disturbance and distress by the sounds were addressed. Finally, several coping strategies came forward, subdivided in avoidance (getting away, covering ears, etc) and problem-oriented coping (complain to teacher). The method employed was in broad lines comparable to that used by Haines et al12 in children aged 10–13. She concluded that noise annoyance in children pertains to the same construct as in adults, and this was later confirmed by others.13 16–18 It is uncertain whether younger children are also able to make such distinctions and thus show a comparable pattern to older children and adults, nor whether they are capable of answering questions during a structured interview regarding their sound environment and the way they are emotionally and physically affected by it in a consistent way.

Objectives

This paper aims to describe and explore the reliability and validity of the key questions of a structured interview developed for preschool children. The questions pertain to preschool children's perception of noise when at school, their bodily and emotional reactions to it, non-specific (stress-related) symptoms and the coping strategies used by them to diminish the detrimental effects of the noise. Aspects related to perceived control and behavioural reactions were left out of the interview, since it was felt that observational methods to measure these aspects would be more suitable to apply in this age group. Bodily reactions to noise in general as well as noise-specific reactions were used to examine the external validity of the children's responses.

Materials and methods

Selection and recruitment

In the period between October 2006 and October 2009, children aged 4–5 and their parents were recruited from seven preschools where interventions were undertaken with the purpose of improving the acoustical qualities in the preschools in Mölndal, Sweden. In total, 63 children and 59 parents filled out the questionnaire before and after the intervention. The response rates ranged from 80% in the parents to 98% in the children. Of the children, two fell outside the age range of 4–5 years and were excluded from further analysis, resulting in a study population of 61 children. Parents signed an informed consent for their children according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Göteborg, Sweden.

Procedure

One month before and 3 months after the intervention, the children were interviewed. In order to diminish the risk of inter-rater variance, the interviews were performed by two trained persons. The interview took on average 20 min and the form was filled in directly by the interviewer. The children were asked questions in a structured way and presented with visual representations of scales on show cards. The answers were filled in by the interviewer directly. When the child was not able to answer the question, they were not prompted to do so. For the core set of questions, see online supplementary appendix 1. For information about the full protocol, please contact the first author.

Study population

Table 1 shows the distribution of age and gender of the children included in the analysis. The 61/59 children, respectively, included in the before–after study are reasonably well distributed over the gender and age groups. All children aged 4–6 years were asked to participate in the interview, and the number of children that took part in the interview per preschool ranged from 4 to 15.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the children (before and after intervention)

| Characteristic | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| Number of respondents (n) | 61 | 59 |

| Gender (%) | ||

| Girls | 48 | 49 |

| Boys | 52 | 51 |

| Age (%) | ||

| 4 years | 52 | 32 |

| 5 years | 48 | 49 |

| 6 years | – | 8 |

Noise exposure assessment and interventions

Noise was measured 1 month before and 3 months after the intervention using a stationary noise level meter (Bruel and Kjaer 2261) with the microphone hanging 0.5 m from the ceiling and personal dosimeters (Larson and Davies Sparks 705+) mounted on the left shoulder of personnel and children in seven preschools. The methods are described in more detail elsewhere.27 28 Stationary measurements during activity in the various rooms showed a moderate reduction of the equivalent A-weighted level. The average reduction after the intervention as compared to before varied between 1.2 and 3.8 dB (LAeq) depending on the room. Children's dosimeters showed that the personal average exposures were high and in the range of 83–85 dB (LAeq) and 117–118 dB (LAFmax) both before and after the intervention; hence, the intervention did not affect personal levels in a measurable way.

Noise perception

Noise perception was measured by means of standard questions. Children were asked how frequently they heard noise from three relevant noise sources in the preschool situation: angry and yelling children, strong and loud sounds and scraping and screeching sounds. Answers were indicated on a five-point Likert scale (ranging from “almost never to very often”) presented as five circles increasing in size and including 1–5 dots.

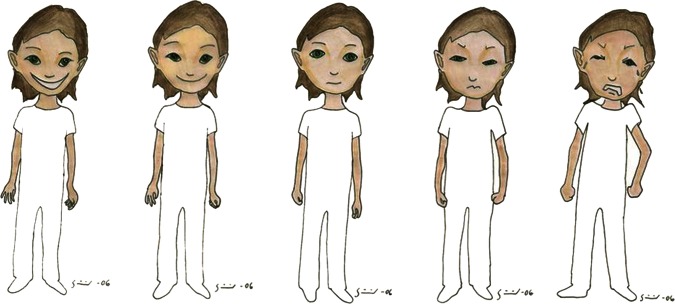

Reaction to noise

Aspects of reaction were measured using the following wording: How do you feel when you hear [sounds of angry, yelling children][loud and strong sounds] [scraping and screeching sounds]. Answers were indicated on a bipolar visual scale representing drawn figures with different facial and bodily expressions ranging from glad/safe to sad/afraid and from kind/friendly to angry/irritated, respectively. The reaction was recoded to a neutral position (code 3) for those children who indicated on the previous question on perception that they did not hear the sound (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Visual representation with a point scale ranging from kind/friendly to angry/irritated.

Coping strategies

For noise experienced at preschool, coping strategies were investigated by asking the children what they did when there was a lot of noise and if they coped, how often. The phrasing was as follows: “When there is a lot of noise what do you do” [go away], [put your hands over your ears][tell your teacher] [raise your voice]and if so how often [almost never to all the time]. First, the answers No or Yes could be given. If the answer was Yes, they were asked to indicate how often on a five-point Likert scale (ranging from “almost never to very often”) presented as five circles increasing in size and including 1–5 dots.

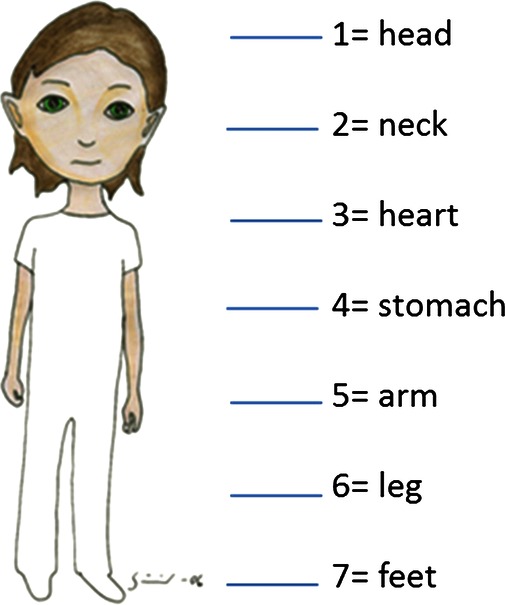

Bodily reactions to noise and symptoms

In order to measure bodily reactions to the three different sounds, the children were asked to indicate per sound source whether they could feel the sounds in their body and if so where they felt it (figure 2) (“when you hear [angry and yelling sounds], [strong and loud sounds],[ scraping and screeching sounds] can you feel it inside you or in your body and if so please point out in the figure where you feel it”). The answers were recoded into location [head] [neck] [arms] [heart] [belly] [legs] [feet] as well as in a number of locations (none vs 1 or more).

Figure 2.

Visual representation of body location.

Non-specific symptoms were inventoried by asking the children what symptoms they had experienced in the past few days at preschool: headache, tummy ache and hoarse voice. Finally, a question was asked about general well-being, making use of a similar figure used for reaction to noise [“in the last days at preschool” have you felt like any of these children in this picture], which was recoded into a 1–5 scale.

Data analysis

In order to test the convergent and divergent validity of the different indices, as a first step, confirmative factor analysis (CFA) was carried out using SAS for Windows (V.9.3) on the reaction and coping questions and perceived health questions. Bodily sensation and health symptoms were included, in order to determine whether children could distinguish between emotional and bodily responses and non-specific symptoms/health complaints. Also, the items on the questions regarding coping strategies were included in the analysis. A high correlation was expected between reactions (both bodily and emotional) to different noise sources, between symptoms and the different coping strategies. CFA is a special form of factor analysis that is used to test whether measures of a construct are consistent with a researcher's understanding of the nature of that construct (or factor) and is therefore suitable for our purpose. The degree of consistency is expressed by several statistical quantities determining the adequacy of model fit to the data, including the standardised root mean square residual (SRMSR) and the adjusted goodness of fit (AGFI). Acceptable model fit is indicated by an SRMSR value of 0.08 or less29 and an AGFI value of 0.95 or more.30 The contribution of each item to a factor is expressed in factor loadings. Owing to the small sample size and departure from normality, diagonally weighted least squares were used to estimate the parameters of the factor model.

In order to test the internal consistency of the components, Cronbach's α's were calculated on the grouped items. Indices were composed by simply summing the separate items. These indices were further tested on their concurrent validity by comparing groups with one or more symptoms due to the different noise sources to a group that reported no symptoms. This was performed for the before condition only by means of a t test assuming unequal variances. Additional analyses were performed on some relevant single items, which were excluded from CFA using non-parametric methods such as Spearman and Mann-Whitney. A limiting factor for all analysis is the relatively small sample size. Traditional psychometrics advise that there should be at least 10 respondents per item, but sample sizes between 50 and 100 subjects are usually considered adequate to evaluate the psychometric properties of measures of social constructs.31

Results

Table 2 shows the prevalence of noise perception, presented per noise source, and emotional reaction, total coping strategies and symptoms.

Table 2.

Prevalence of noise perception, reaction, symptoms and coping

| Characteristic | Before (%) (n=61) | After (%) (n=59) |

|---|---|---|

| Perception noise source* | ||

| Angry and yelling: Source 1 | 67 | 58 |

| Loud and strong: Source 2 | 57 | 51 |

| Scraping and Screeching: Source 3 | 35 | 18 |

| Location bodily reaction | ||

| At least 1 location | 70 | 80 |

| Source 1 | 54 | 49 |

| Source 2 | 54 | 56 |

| Source 3 | 51 | 49 |

| Angry reaction (score over 11)† | 13 | 5 |

| Prevalence of symptoms (score over 11)† | 7 | 4 |

| Coping (score over 15)† | 13 | 16 |

*Percentage of children scoring in the highest two categories.

†Percentage of children scoring in the highest two categories per sum-score.

Worthwhile mentioning is also the percentage of children indicating that they never heard the sound was 17% and 19% for the angry and yelling sounds, 22% and 22% for the loud sounds, and 35% and 52% for the scraping and screeching sounds in the before and after conditions, respectively.

Reaction and coping in children: construct validity

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) with categorical indicators were carried out to verify the a priori structure pertaining to perception, emotional reaction, symptoms and coping strategies in the before and after conditions. The perception scales [How often do you hear angry and yelling children, strong and loud sounds and scraping and screeching sounds] as well as the sad reaction scales showed too much instability to be consider suitable for further analysis. Likewise, the items pertaining to noise perception per source and low well-being were too unstable or loaded on many factors and were therefore treated as single items in further analysis (see table 3). A three-factor model was fitted to the remaining 10 items pertaining to angry reactions, symptoms and coping. The model fit was good with an SRMSR of 0.08 and an AGFI of 0.97 in the before condition, but weaker in the after condition with an SRMSR of 0.12 and an AGFI of 0.91. For the before condition, the loadings are in the ranges 0.58–0.77, 0.41–0.78 and 0.51–0.71 for the three factors, respectively. It was decided to take the before analysis as a point of departure and to test the reliability of the scales based on the measurements in the before and after conditions.

Table 3.

Factor loadings, goodness of fit, internal consistency and interrelations

| Components/before |

Components/after |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction | Coping | Symptom | Reaction | Coping | Symptom | ||

| Source1_angry | 0.63 | 0.33 | |||||

| Source2_angry | 0.77 | 0.55 | |||||

| Source3_angry | 0.58 | 0.73 | |||||

| Go away | 0.78 | 0.32 | |||||

| Cover ears | 0.52 | 0.46 | |||||

| Tell teacher | 0.41 | 0.62 | |||||

| Raise voice | 0.57 | 0.72 | |||||

| Headache | 0.71 | 0.53 | |||||

| Tummy ache | 0.67 | 0.18 | |||||

| Hoarse voice | 0.51 | 0.61 | |||||

| Cronbach's α | 0.63 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.52 | |

| SRMSR | 0.08 | 0.12 | |||||

| AGFI | 0.97 | 0.91 | |||||

| Before | a | b | c | d | e | f | g |

| a. Perception yelling children | 1 | 0.48* | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.23* | −0.12 |

| b. Perception loud and strong sounds | 1 | 30* | 0.24* | 0.25* | 0.33* | 0.00 | |

| c. Perception scraping and screeching sounds | 1 | 0.23* | 0.37* | 0.25* | 0.23* | ||

| d. Angry reaction | 1 | 0.33* | 0.15 | 0.22* | |||

| e. Symptoms | 1 | 34* | 0.56* | ||||

| f. Coping strategies | 1 | −0.10 | |||||

| g. Low well-being | 1 | ||||||

*Significant at 0.05 level/missing values pairwise deletion.

Reliability in terms of internal consistency

Three groups of variables pertaining to Angry Reaction, Coping and Symptoms were tested on their internal consistency expressed in α's for the two measurements (table 3, row 11). The analysis yielded homogeneous scales with comparable α's over the measurements ranging from 0.56 to 0.75. The relatively low α's in the after condition are partly due to the test length and imply the risk of underestimating/attenuating the relationships between the variables and other variables.32 However, based on the findings in the before condition, it was considered justified to compose three indices by summing the scores on the separate items within each factor and to test the distributions on normality. Deviations of normality were slight and most pronounced in the symptom scales.

Correlation analyses between these indices and items related to perception of noise and low well-being were studied for the before situation only (table 3) and showed moderate to weak associations between perception and outcomes, but mostly in line with our expectations. Perception of scraping and screeching sounds was most strongly associated with angry reactions, coping, symptoms as well as low well-being being followed by perceived loud sounds. Coping strategies were associated most strongly with symptoms and the highest association was found between symptoms and low well-being. Since items referring to sad reactions to the different sounds did not form one factor and the bipolar items do not allow for correlational analysis, separate analysis was performed after dichotomising the scores on sad reaction items. Mann-Whitney analysis showed that sadness due to loud noises was associated with symptoms (Z value=2.3/p=0.021) and sad reaction due to scraping/screeching sounds with symptoms (Z value=3.4/p=0.001) and coping strategies (Z value=2.7/p=0.008), while sadness due to yelling sounds was found not to be associated with any of the indices on angry reaction, symptoms or coping.

Concurrent validity

As a last step in the psychometric evaluation, the associations between bodily reactions to noise and the three indices and the single item low well-being were analysed to explore the concurrent validity. This refers to the accuracy of the relevant test scores to estimate an individual state on a criterion, in this case bodily reaction (general and noise source specific).

The rationale behind this analysis is that angry reaction, amount of coping strategies (number and frequency) and symptoms as well as low well-being are expected to be associated with bodily reactions. The associations between bodily reactions to noise with these relevant test-scores were studied by means of t test. Hereby, dichotomous groups were formed based on any bodily reaction and bodily reactions per noise source, respectively, versus none. Distributions were checked per group and angry reaction was dropped from the analysis because the majority of data points in the group with no bodily reaction contained only children who had indicated that they did not hear the sound. Subsequently, the mean scores on the remaining indices and the low well-being item were compared between groups. Table 4 presents the results.

Table 4.

Bodily reaction and children's coping, symptoms and low well-being (before condition)

| Bodily reaction to any source | Bodily reaction to yelling sounds | Bodily reaction to loud sounds | Bodily reaction to scraping and screeching sounds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom | −4.67** | −2.18* | −2.34* | 2.69* |

| Coping strategies | −2.62* | −2.58* | −1.53 | −2.04* |

| Low well-being | −1.97 | −2.34* | −1.05 | −1.50 |

Observed t statistic/p value <0.05 marked as * and p<0.001 marked as **.

The t test yielded significant differences in means on symptoms before for groups based on the presence of any bodily reactions as well as the presence of bodily reaction to the separate sources. The same pattern was found for coping with the exception of loud sounds. Low well-being when at school in the before condition, measured with a single item, was shown to be significantly associated with bodily reaction to loud sounds only, while any bodily reaction just failed significance. In the after condition, this pattern was only partly confirmed for symptoms with any bodily reaction and low well-being with any bodily reaction. Since the t test assumes normal distribution, in addition non-parametric tests were applied. Further analysis showed that each hypothesis with p value <0.05 for the t test had Mann-Whitney p values not exceeding 0.08.

Discussion

The results of the psychometric evaluation indicate that preschool children are able to make a distinction between reactions to noises and emotional and bodily reactions as measured by means of visual representations of reactions and representation of the location of bodily reactions. As in adults,33 the interrelations between angry reactions to different sounds and noises were relatively high, while the relation between angry reactions and symptom-related aspects was lower: in other words, reaction and symptoms can be considered as separate dimensions. This is also consistent with the findings among schoolchildren (9–11 years) in the RANCH study18 and a survey among 207 children (aged 13–14 years).34 35 Furthermore, the results are in agreement with the results of a RANCH substudy36 in which it was found that children were capable of reliably indexing complex soundscapes and providing perceptual scales that were in striking agreement with the perceptual scales provided by adults. We also found that angry reactions to noise could be distinguished from coping strategies. Comparing the elements of the correlation matrix in the before condition for perceptions of the different sound sources and its effects, we conclude that the scraping and screeching sounds play a prominent role, with significant associations for angry reaction, coping and symptoms. While coping was significantly associated with all sounds, yelling sounds were not associated with angry reactions or symptoms. Based on the pattern, we hypothesise that there is a pathway from the perception of scraping and screeching sounds via angry reactions and coping to symptoms and via symptoms to low well-being.

An important finding is that children, compared to adults, seem to have a tendency to describe reaction to noise in a somatic way: they literally feel the noise in their body, especially in the head, heart and tummy.

Both the (angry) reaction and symptom indices are significantly associated with general low well-being while at school and these responses tend to be sound specific. While loud and yelling sounds are only associated with coping, the perception of scraping and screeching sounds is significantly associated with angry reactions, coping as well as symptoms. This finding is important in view of future interventions at preschools as scraping and screeching sounds mainly originate from friction between surfaces, such as chairs being pulled across the floor or table wares moved on the table top. To our knowledge, no standards exist that give guidance on how to predict these sounds, which makes them problematic to systematically address. The four coping items included in the questionnaire pertain to active and avoidant behaviour, a distinction which is confirmed in studies among older children and adults, but also came forward from the focus group discussions with children.24 Results of CFA analysis showed a high intercorrelation between the different coping strategies, with a slight tendency for a two sub-factors structure, pertaining to problem-oriented coping and avoidance. This has implications for the interpretation of the coping index: it refers to the number and frequency of strategies employed rather than more or less effective strategies to cope with environmental noise. Future work should attempt to expand the number of items related to these different strategies which young children employ to cope with classroom noise.

An explorative comparison of children's symptom report and bodily reactions reveals a reasonably consistent pattern and indicates satisfactory concurrent validity of most of the indices for the before situation.

The strength of this study lies in the fact that the questions posed to the children were based on focus group discussion and worded in their own ‘language’. A major limitation is the relatively small sample size. Future research on larger groups of preschool children will be needed to further refine the questions, in particular the questions pertaining to well-being and coping. Such an instrument will allow for studying development in reaction over time as well as the evaluation of noise-reducing measurements in preschool in an unobtrusive and playful manner.

Previous studies have suggested that children have fewer possibilities for controlling noise or have a less developed coping repertoire than adults.20 23 Development of coping strategies would be an important target for future research in this group: noise-induced behaviours at a young age (eg, learnt helplessness) might affect other aspects of later life functioning and the development of disease. Furthermore, this study shows that emotional reaction (angry and sad) is not the only relevant indicator of the effects of community noise in children; also, bodily reactions, symptoms, coping behaviour and well-being are shown to be important.

Conclusion

The main conclusion to be drawn from this study is that young children's angry reaction and bodily reactions to coping with noise can be reliably measured with a structured interview, including visual representation questions. In accordance with what was found in adults33 and children aged 9–11,18 21 we found that younger children are also able to distinguish between emotional reactions, symptoms, coping and well-being. Compared to adults, younger children tend to describe their reactions to noise in a somatic way. After further development of the instrument discussed in this paper, we foresee studies into young children's reactions to coping with noise on a larger scale.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Agneta Agge and Lena Samuelsson for their competence in carrying out the interviews. We also want to thank the participating children and their parents. The study was funded by the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social research.

Footnotes

Contributors: KPW and LD conceived the idea of the study and were responsible for the development of the questionnaire. KPW carried out the study with data acquisition, took part in the interpretation of the data and drafted the article. IvK was responsible for the analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting the article and revising it. LD has revised the article and all three authors have approved the final version to be published.

Funding: Swedish Council for Working Life and Social research.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Research Ethic Committee Gotheburg, Sweden.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.vk08q?

References

- 1.Voss P. Noise in children's day care centers. AkustikNet A/S. Denmark, 2005:23–5 www.akustiknet.dk (accessed 26 Nov 2012)

- 2.Maxwell LE, Evans GW. The effects of noise on preschool children's prereading skills. J Environ Psychol 2000;20:91–7 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berglund B, Lindvall T, Schwela DH, et al. Guidelines for community noise. World Health Organisation (WHO), 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawai K. Effect of sound absorption on indoor sound environment of nursery school classrooms. In: Burgess M. Proceedings of 20th International Congress on Acoustics, ICA. Sydney, Australia, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg F, Blair J, Benson P. Classroom acoustics: the problem, impact, and solution. Lang Speech Hear Serv Schools 1996;27:16–20 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Passchier-Vermeer W. Noise and Health of Children. Report PG/VGZ/2000.042 Leiden: Netherlands Organization for Applied Scientific Research (TNO), 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dettling AC, Parker SW, Lane SK, et al. Quality of care and temperament determine whether cortisol levels rise over the day for children in full-day child care. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2000;25:819–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans GW. The environment of childhood poverty. Am Psychol 2004;59:77–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blair C, Granger D, Peters Razza R. Cortisol reactivity is positively related to executive function in preschool children attending head start. Child Dev 2005;76:554–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McAllister , Granqvist S, Sjölander P, et al. Child voice and noise: a pilot study of noise in day cares and the effects on 10 children's voice quality according to perceptual evaluation. J Voice 2009;5:587–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stansfeld SA, Berglund B, Clark C, et al. Aircraft and road traffic noise and children's cognition and health: a cross-national study. Lancet 2005;365:1942–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haines MM, Brentnall SL, Stansfeld SA, et al. Qualitative responses of children to environmental noise. Noise Health 2003;5:19–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lercher P, Evans GW, Meis M, et al. Ambient neighbourhood noise and children's mental health. Occup Environ Med 2002;59:380–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.May M, Emond A, Crawley E. Phenotypes of chronic fatigue syndrome in children and young people. Arch Dis Child 2010;4:245–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stansfeld SA. The effects of noise on health; new challenges and opportunities. In:. Proceedings of the 8th European Conference on Noise Control, Euronoise , Institute of Acoustics, Edinburough, UK, 2009. ISBN: 9781615676804 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark C, Stansfeld SA. The effect of transportation noise on health and cognitive development: a review of recent evidence. Int J Comp Psychl 2007;20:145–58 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babisch W, Schulz C, Seiwert M, et al. Noise annoyance as reported by 8–14-year-old children. Environ Behav 2012;44:68–86 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Kempen EMM, van Kamp I, Stellato R, et al. Children's annoyance reactions to aircraft noise and road traffic noise: the RANCH-project. J Acoust Soc Am 2009;125:895–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lercher P, Evans GW, Meis M. Ambient noise and cognitive processes among primary schoolchildren. Environ Behav 2003;35:725–35 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bistrup ML. Prevention of adverse effects of noise on children. Noise Health 2003;5:59–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haines MM, Stansfeld SA, Job RFS, et al. Chronic aircraft noise exposure, stress responses, mental health and cognitive performance in school children. Psychol Med 2001;31:265–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Regecová V, Kellerová E. Effects of urban noise pollution on blood pressure and heart rate in preschool children. J Hypertens 1995;13:405–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belojevic G, Jakovljevic B, Vesna S, et al. Urban road-traffic noise and blood pressure and heart rate in preschool children. Environ Int 2008;34:226–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maxwell LE. Preschool and day care environments. In: Lueder R, Rice V, eds. Child Ergonomics. New York: Taylor and Francis, 2007:653–88 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dellve L, Samuelsson L, Persson Waye K. Preschool children's experience and understanding of their soundscape. Qual Res Psychol 2013;10:1–13 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Persson Waye K, Larsson P, Hult M. Perception and measurement of preschool sound environment before and after acoustic improvements. In: Bolton JS. 38th International Congress and Exposition on Noise Control Engineering, INTER-NOISE, Ottawa, Canada, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Persson Waye K, Agge A, Hillström J, et al. Being in a preschool sound environment- annoyance and subjective symptoms among personnel and children. Perception and measurement of preschool sound environment before and after acoustic improvements. 39th International Congress and Exposition on Noise Control Engineering, INTER-NOISE. Lisbon, Portugal, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: coventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 1999;6:1–55 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shevlin M, Miles JNV. Effects of sample size, model specification and factor loadings on the GFI in confirmatory factor analysis. Pers Individ Dif 1998;25:85–90 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sapnas KG, Zeller RA. ‘Minimizing sample size when using exploratory factor analysis for measurement’. J Nurs Meas 2002;10:135–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neal S. Uses and abuses of coefficient alpha. Psychol Assess 1996;8:350–3 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Kamp I. Indicators of annoyance: a psychometric approach; the measurement of annoyance and interrelations between different measures. In: Boone R. International Congress and Exposition on Noise Control Engineering, INTER-NOISE Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boman E, Enmarker I. Factors affecting pupils’ noise annoyance in schools: the building and testing of models. Environ Behav 2004;36:207–28 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Enmarker I, Boman E. Noise annoyance responses of middle school pupils and teachers. J Environ Psychol 2004;24:527–36 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gunnarsson AG, Berglund B, Haines M, et al. Psychological restoration in noise. In: Jong RG, de Houtgast T, Franssen EAM, et al. Proceedings of the 8th International Congress on Noise as a Public Health Problem. Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2003:159–60 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.