Abstract

Objectives

To determine trends and risk factors for severe perineal trauma between 2000 and 2008.

Design

This was a population-based data study.

Setting

New South Wales, Australia.

Participants

510 006 women giving birth to a singleton baby during the period 2000–2008.

Main outcome measures

Rates of severe perineal trauma between 2000 and 2008 and associated demographic, fetal, antenatal, labour and delivery events and factors.

Results

There was an increase in the overall rate of severe perineal trauma from 2000 to 2008 from 1.4% to 1.9% (36% increase). Compared with women who were intact or had minor perineal trauma (first-degree tear, vaginal graze/tear), women who were primiparous (adjusted OR (AOR) 1.8 CI (1.65 to 1.95), were born in China or Vietnam (AOR 1.1 CI (1.09 to 1.23), gave birth in a private hospital (AOR 1.1 CI (1.03 to 1.20), had an instrumental birth (AOR 1.8 CI (1.65 to 1.95) and male baby (AOR 1.3 CI (1.27 to 1.34) all had a significantly higher risk of severe perineal trauma. Only giving birth to a male baby, adjusted for birth weight (AOR 1.5 CI (1.44 to 1.58), remained significant, when women with severe perineal trauma were compared with all other women not experiencing severe perineal trauma. This association increased over the study period.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first time that having a male baby has been found to exert such a strong independent risk for severe perineal trauma and the increasing significance of this in recent years needs further exploration.

Article summary.

Article focus

To examine trends in severe perineal trauma in New South Wales (NSW) (2000–2008).

To examine risk factors for severe perineal trauma in NSW (2000–2008).

Key messages

Severe perineal trauma has increased by 36% in NSW between 2000 and 2008.

Only giving birth to a male, adjusted for birth weight, remained significant when women with severe perineal trauma were compared with all other women.

The impact of male gender on severe perineal trauma has become increasingly significant in more recent years.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The strength of this study lies in the large sample size of over half a million women.

Previous validation studies show that perineal status is very accurately recorded.

Limitations are the restricted number of variables that are included and the scarcity of specific information on potential confounders.

Introduction

Severe perineal trauma occurs in 0.5–10% of the obstetric population1–4 and can occur spontaneously during an unassisted vaginal birth or as a result of obstetric intervention such as episiotomy and/or instrumental birth.5 6 Current Australian data reports rates of 1.7%, which ranges from 1.1% in Tasmania to 3% in the Australian Capital Territory.7

Severe perineal trauma during childbirth is defined as a third-degree tear, which involves injury to the perineum involving the anal sphincter complex; or a fourth-degree tear, which involves injury to the perineum including the external and internal anal sphincter and rectal mucosa.8 There is some evidence that the incidence of severe perineal trauma may be increasing on an international scale,4 9 but it is unclear if this is due to better recognition and reporting or an actual rise.

Severe perineal trauma is associated with maternal morbidity such as perineal pain, incontinence and dyspareunia.10–12 The significant psychological ramifications of severe perineal trauma are under-researched.13

Risk factors during the antenatal period associated with an increased incidence of severe perineal trauma include parity, maternal age, ethnicity and nutritional status, as well as previous experience of perineal trauma, fetal weight and abnormal collagen synthesis.14–16 Intrapartum risk factors include fetal presentation (eg, occipito-posterior position), episiotomy (especially midline), instrumental birth, prolonged second stage of labour, birth position and shoulder dystocia.14 17–20

The aim of this study was to examine trends and risk factors for severe perineal trauma in New South Wales (NSW) between 2000 and 2008.

Methods

Data sources

Birth data for the time period 1 July 2000 to 30 June 2008 of all singleton births was provided by the NSW Department of Health as recorded in the NSW Midwives Data Collection (MDC). This legislated, population-based surveillance system contains maternal and infant data on all births of ≥400 g birth weight or ≥20 weeks’ gestation. While there are around 65 hospitals represented in the data, and there are variations in severe perineal trauma rates between hospitals in the NSW maternity reports, the linked data used for this study pooled all the hospitals and we were only able to separate out public and private hospitals.

The recording of perineal status was altered on MDC in 2006. Prior to 2006, perineal status was recorded as intact/graze, first-degree, second-degree, third-degree, fourth-degree tear, episiotomy and combined episiotomy and tear. Post 2006, combined episiotomy and tear was removed. The two versions of the data were merged for the purpose herein. The data item ‘Episiotomy Yes/No’ was also utilised. The accuracy of the recording of perineal status has previously been shown to have a κ of 0.84 and 0.82 in two separate and individual studies.21 22 The positive predictive values of , first-degree, second-degree, third-degree and fourth-degree tears have been reported as 76.6, 96.6, 72.8 and 100, respectively. For the purpose of this study, group 1—intact/minor perineal trauma includes women with intact perineal status, grazes and first-degree tears (representing no or minor damage with lower morbidity). Group 2—major perineal trauma includes women with second-degree tears, episiotomy and episiotomy and first-degree and second-degree tears. Group 3—severe perineal trauma includes women with third-degree, fourth-degree tears and episiotomies with extension to third-degree and fourth-degree tears. Mediolateral episiotomy is most commonly used in Australia. Only women recorded as having a vaginal delivery were included in this study. Fetal sex and gestation adjusted percentiles were calculated using the data provided within the datasets.

Ethical approval was obtained from the NSW Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee, Protocol No.2010/12/291.

Data analysis

Descriptive short-term and long-term morbidity associated with all types of perineal trauma was produced utilising SPSS V.19 (IBM) with contingency tables. Associate factors between groups 1 and 2 (intact/minor perineal trauma and major trauma) and 3 (severe perineal trauma) and demographic data, antenatal, labour and delivery events were analysed using logistic regression and multinomial regression techniques in a forward stepwise fashion utilising the Wald method with the inclusion of variables with a significance of p<0.01.

Frequency distributions were used to classify the population and descriptive statistics of the morbidity outcomes. Adjusted OR (AOR) was calculated between factors and events and binary logistic regression techniques were applied to potentially associated demographic, fetal, antenatal, labour and delivery events and factors and the incidence of severe perineal trauma. The time period of the study was divided into 3-year epochs (2000–2002, 2003–2005, 2006–2008) when examining the trends in rates and associated factors for severe perineal trauma. Birth weight centiles adjusted for sex and gestation at birth were created from the data provided within the dataset. This was able to be undertaken owing to the size of the dataset and increased the validity for accurate comparisons. Statistical results were produced using SPSS V.19 (IBM). The level of significance was set at <0.001 to minimise the false-positive results in this large cohort.

Results

Between 1 July 2000 and 30 June 2008, there were 510 006 vaginal births. Nearly all of these births occurred in hospital (95%) and 71% of the women were born in Australia. Of the women giving birth vaginally, 14.2% had an instrumental birth and 0.6% had a vaginal breech birth (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and mode of birth of all women giving birth in NSW between 2000 and 2008 and in three time epochs (2000–2002, 2003–2005, 2006–2008)

| All women | 2000–2002 | 2003–2005 | 2006–2008 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of births | 510006 | 160160 | 186310 | 163536 |

| Age of women at delivery (mean and SD) | 29.7 (5.55) | 29.5 (5.51) | 29.7 (5.53) | 30.0 (5.60) |

| Percentage of primiparous women | 40.6 | 40.2 | 41.0 | 40.4 |

| Percentage of male babies | 50.9 | 50.9 | 51.0 | 50.9 |

| Place of birth | ||||

| Hospital (%) | 94.5 | 94.9 | 94.6 | 94.0 |

| Birth centre (%) | 3.30 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.7 |

| Planned birth centre transferred to hospital (%) | 1.30 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Planned Home Birth (%) | 0.20 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Planned Home Birth transferred to Hospital (%) | 0.01 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Born Before Arrival | 0.60 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Type of birth | ||||

| Normal vaginal delivery | 85.3% | 85.6 | 85.4 | 84.7 |

| Forceps | 4.8% | 5.1 | 4.5 | 4.7 |

| Ventouse | 9.4% | 8.6 | 9.6 | 10.0 |

| Vaginal breech | 0.6% | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Country of birth of mother | ||||

| Australia | 71.6% | 72.5 | 71.9 | 70.3 |

| New Zealand | 2.6% | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.7 |

| England | 2.2% | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| Vietnam | 2.2% | 2.2 | 2.2 | 1.9 |

| China | 2.1% | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.0 |

| Lebanon | 2.1% | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.2 |

| Other | 17.2% | 17.2 | 17.2 | 18.6 |

There was a significant increase in the overall rate of severe perineal trauma from 2000 to 2008 from 1.4% to 1.9% (figure 1). This increase was most evident in the category ‘third-degree tears’ and in the percentage of women who had severe perineal trauma associated with extensions following an episiotomy.

Figure 1.

Trends in severe perineal trauma by degree of trauma and associated with extension of episiotomy (2000–2008).

Results of univariate and stepwise regression models are provided in table 2.

Table 2.

Factors associated with severe perineal trauma compared with intact/minor trauma

| Intact/minor | Severe | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| 12–25 | 97.7% | 2.3% | 1.1 (0.99 to 1.11) | ||

| 26–35 | 97.6% | 2.4% | 1.0 (0.95 to 1.11) | ||

| >35 | 97.7% | 2.3% | |||

| Parity | |||||

| Multiparous | 97.9 | 2.1% | 1.8 (1.65 to 1.95) | <0.0001 | |

| Primiparous | 97.3 | 2.7% | 1.3 (1.29 to 1.31) | ||

| Country of birth | |||||

| Other | 97.7% | 2.3% | 1.2 (1.05 to 1.30) | 1.1 (1.09 to 1.23) | *0.04 |

| China/Vietnamese | 97.4% | 2.6% | |||

| Gestational diabetes | |||||

| No | 97.7% | 2.3% | 1.1 (0.94 to 1.20) | ||

| Yes | 97.5% | 2.5% | |||

| Hypertensive disorder of pregnancy | |||||

| No | 97.8% | 2.2% | 1.0 (0.85 to 1.1) | ||

| Yes | 97.8% | 2.2% | |||

| Level hospital of birth | |||||

| 1 | 98.1% | 1.9% | 1.0 (0.72 to 1.67) | ||

| 2 | 97.9% | 2.1% | 1.2 (0.79 to 1.77) | ||

| 3 | 97.7% | 2.3% | 1.2 (0.77 to 1.71) | ||

| 4 | 97.8% | 2.2% | 1.2 (0.78 to 1.71 | ||

| 5 | 97.8% | 2.2% | 1.2 (0.81 to 1.79) | ||

| 6 | 97.2% | 2.8% | |||

| Hospital type | |||||

| Public | 97.7% | 2.3% | 1.2 (1.13 to 1.27) | 1.1 (1.03 1.20) | 0.004 |

| Private | 97.3% | 2.7% | |||

| Onset of labour | |||||

| Spontaneous | 97.7% | 2.3% | 1.0 (0.97 to 1.10) | ||

| Induced | 97.6% | 2.4% | |||

| Delivery type | |||||

| Normal vaginal delivery | 97.8% | 2.2% | 0.8(0.59 to 1.18) | 1.8 (1.65 to 1.95) | <0.0001 |

| Vaginal breech birth | 98.0% | 2.0% | 2.0 (1.89 to 2.16) | ||

| Instrumental delivery | 95.7% | 4.3% | |||

| Epidural usage | |||||

| No epidural | 97.9% | 2.1% | 1.2 (1.12 to 1.30) | 1.0 (0.94 to 1.10) | 0.53 |

| Epidural | 97.5% | 2.5% | |||

| Gender of baby | |||||

| Female baby | 98.2% | 1.8% | 1.6 (1.50 to 1.65) | 1.3 (1.27 to 1.34) | <0.0001 |

| Male baby | 97.1% | 2.9% | |||

| Birth weight centile >90th | |||||

| Yes | 97.7% | 2.3% | 1.0 (0.95 to 1.12) | ||

| No | 97.6% | 2.4% | |||

Compared with women who had an intact perineum or minor perineal trauma ( first-degree tear and graze), women who were primiparous (AOR 1.8 CI (1.65 to 1.95), were born in China or Vietnam (AOR 1.1 CI (1.09 to 1.23), gave birth in a private hospital (AOR 1.1 CI (1.03 to 1.20), had an instrumental birth (AOR 1.8 CI (1.65 to 1.95) or had a male baby (AOR 1.3 CI (1.27 to 1.34) all had a significantly higher risk of severe perineal trauma.

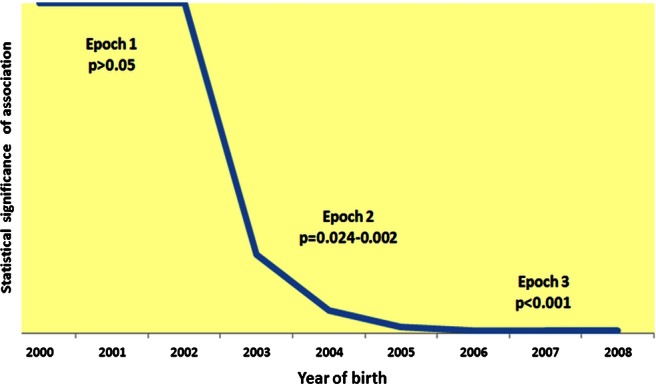

When we compared women in two groups, those having severe perineal trauma with those not having severe perineal trauma, only the male sex (AOR 1.5 CI (1.44 to 1.58) remained significant (table 3). We examined the changes over three epochs and found that this trend was more significant in the last epoch than in the first (figure 2). There was no evidence of a change in mean overall birth weight over the study period time or in male birth weight over the 90th centile (figure 3). When the male sex appeared as a major risk factor for severe perineal trauma, we examined other potential associated factors including smoking. An examination of smoking in NSW over the 8-year period showed an overall decrease (4.2%; figure 4).

Table 3.

Factors associated with severe perineal trauma compared with no/all other trauma

| No/all other trauma (%) | Severe (%) | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| 12–25 | 98.4 | 1.6 | 1.0 (0.94 to 1.07) | |

| 26–35 | 98.4 | 1.6 | 1.0 (0.92 to 1.07) | |

| >35 | 98.4 | 1.6 | ||

| Parity | ||||

| Multiparous | 98.4 | 1.6 | 1.0 (0.96 to 1.05) | |

| Primiparous | 98.4 | 1.6 | ||

| Country of birth | ||||

| Other | 98.4 | 1.6 | 1.0 (0.93 to 1.10) | |

| China/Vietnamese | 98.4 | 1.6 | ||

| Gestational diabetes | ||||

| No | 98.4 | 1.6 | 1.0 (0.92 to 1.18) | |

| Yes | 98.4 | 1.6 | ||

| Hypertensive disorder of pregnancy | ||||

| No | 98.5 | 1.5 | 1.0 (0.86 to 1.35) | |

| Yes | 98.5 | 1.5 | ||

| Level hospital of birth | ||||

| 1 | 98.6 | 1.4 | 1.1 (0.74 to 1.72) | |

| 2 | 98.5 | 1.5 | 1.2 (0.78 to 1.75) | |

| 3 | 98.4 | 1.6 | 1.1 (0.76 to 1.68) | |

| 4 | 98.4 | 1.6 | 1.1 (0.76 to 1.69) | |

| 5 | 98.4 | 1.6 | 1.2 (0.78 to 1.72) | |

| 6 | 98.4 | 1.6 | ||

| Hospital type | ||||

| Public | 98.4 | 1.6 | 1.0 (0.96 to 1.08) | |

| Private | 98.5 | 1.5 | ||

| Onset of labour | ||||

| Spontaneous | 98.4 | 1.6 | 1.0 (0.97 to 1.08) | |

| Induced | 98.5 | 1.5 | ||

| Delivery type | ||||

| Normal vaginal delivery | 98.5 | 1.5 | 0.87(0.62 to 1.23) | |

| Vaginal breech | 98.7 | 1.3 | 1.1 (1.01 to 1.16) | |

| Instrumental delivery | 98.3 | 1.7 | ||

| Epidural usage | ||||

| No epidural | 98.5 | 1.5 | 1.0 (0.95 to 1.09) | |

| Epidural | 98.6 | 1.6 | ||

| Gender of baby | ||||

| Female baby | 98.7 | 1.3 | 1.5 (1.44 to 1.58) | 1.5 (1.44 to 1.58) |

| Male baby | 98.1 | 1.7 | ||

| Birth weight centile >90th | ||||

| Yes | 98.4 | 1.6 | 1.0 (0.95 to 1.12) | |

| No | 98.4 | 1.6 | ||

Figure 2.

Statistical significance of association between male sex and severe perineal trauma by epoch.

Figure 3.

Percentage of male babies >90th centile over time.

Figure 4.

Percentage of all women and sex-specific baby rate of smoking over time.

Discussion

It appears that the incidence of severe perineal trauma is increasing in NSW, particularly third-degree tears. The finding that the male sex, following adjustment for weight and gestation, is an independent risk factor for severe perineal trauma is perplexing. The associated effect of the male sex also increases over the time of the study period. To our knowledge, this is the first time that the male sex has been associated with severe perineal trauma.

It is most likely a viable argument that certain features of the male fetus, such as larger head circumferences23 or wider shoulder diameters, are somehow contributing to this effect.24 25 Patumanond et al found that risk of shoulder dystocia was higher in male infants compared with female infants regardless of birth weight. It has also been postulated that male infants produce higher levels of growth hormones,26 that makes male infants have a more solid body mass. Differences in male and female body structure and composition (sexual dimorphism)27 28 may be a plausible explanation. Literature reports that male newborns are heavier, longer, have larger heads, wider shoulder width, chest size and body mass than females, though females have greater skin fold thickness.29 30 In the final weeks of pregnancy, male infants lose fat and gain more weight than female infants31 with the sexual dimorphism becoming more pronounced. This, however, does not explain why the male sex became more pronounced over time in this study, particularly in recent years, unless sexual dimorphism is changing.

Another possible explanation for the increasing impact of the male sex on severe perineal trauma is the decline in smoking over the past decade (4.2%). A study published by Zaren et al found a negative effect on fetal growth from maternal smoking to be more marked in the male fetus than the female. This included birth weight and mean biparietal diameter measurements. The authors conclude that an intrauterine growth velocity and a different hormonal milieu are suggested as possible explanations for the greater male susceptibility.32 In another study, we found that women who smoked were significantly less likely to have an admission in the year following birth for vaginal repair following primary repair, rectal/anal repair following primary repair, fistula repair and urinary/fetal incontinence repair associated with severe perineal trauma compared with those who did not smoke.33 In other studies, smoking has been found to be protective against the development of pre-eclampsia.34

Other factors such as more intervention during birth may also be having a subtle effect on this outcome.35 Intervention during childbirth has increased significantly in Australia in the last decade.7 Melamed et al found that women carrying a male fetus were at increased risk for operative delivery for non-reassuring heart rate and failed instrumental birth. Other studies have found male sex to be a risk factor for gestational diabetes, cord complications, caesarean delivery, meconium and low Apgars.36 Other studies show equivocal outcomes,37 and there is still not a clear understanding of the possible mechanisms between male sex and pregnancy outcome.35

We found that the rate of severe perineal trauma had increased by 36% between 2000 and 2008 and much of this increase was associated with third-degree tears. There is evidence that the incidence of severe perineal trauma may also be increasing on an international scale, but it is unclear if this is due to better recognition and reporting or an actual rise. Reporting can vary as well when it comes to severe perineal trauma, with some studies not including extensions to third-degree and fourth-degree tears following episiotomy. We found severe perineal trauma rate to be increased between 0.3% and 0.6% when these extensions were added. Where the episiotomy rates are higher, such as in private hospitals, this may lead to a serious underestimation of severe perineal trauma rates and incorrect conclusions being drawn.38 39 While in our study there were associations between primiparity, Asian ethnicity, private hospital birth and instrumental birth when we compared the severe perineal trauma group with the no/minor perineal trauma group, this was not seen when compared with all women not experiencing severe perineal trauma. In previous prospective studies that we undertook, a link was found between Asian ethnicity, primiparity, instrumental birth and large infant birth weight.15 40

The apparent rise in severe perineal trauma needs to be explored further to determine whether this is an actual rise or is simply due to better identification and reporting. Studies have shown that, with increased vigilance and appropriate examination, the detection rate of third-degree/fourth-degree tears are more than doubled.2 41

Other possible explanations for the increase of obstetric anal sphincter injuries may be related to changes in clinical practice, including reclassification of third-degree tears (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Green-top Guideline No 29, 2007), decreased skill in the appropriate use of episiotomy and high intervention rates in childbirth.

The significant morbidity associated with severe perineal trauma and the impact on women's lives is still not well understood and there are limited data on women's experiences.13 42 reported that approximately 30–50% of women who sustain a third-degree or fourth-degree tear will suffer some degree of perineal pain, chronic anal incontinence, fecal urgency and dyspareunia (Sultan et al, 1994).

There are significant advantages of using population-based datasets such as MDC, including the size of the dataset, the guaranteed accuracy of a validated dataset and the anonymous nature of the results therein. The limitations are the limited number of variables that are included and the scarcity of specific information on potential confounders; for example, we could not control for shoulder dystocia and occipital posterior position. We are reassured by previous validation studies, however, that perineal status is very accurately recorded.21 22 While we could control for birth weight, which appears not to have increased over the study period, we could not control for maternal body mass index, which is known to have increased.43 44

Conclusion

There was a significant increase in the overall rate of severe perineal trauma in NSW from 2000 to 2008, reflecting observations from other studies. While primiparity, Asian ethnicity, birth in a private hospital, instrumental birth and male sex were significant risks for severe perineal trauma compared with women with no or minor trauma, only male sex remained significant when compared with all women experiencing or not experience severe perineal trauma. The association between severe perineal trauma and male sex has increased in more recent years and it is unclear why this might be the case. More research is needed to determine why the severe perineal trauma rate is increasing and whether there are population changes or iatrogenic influences that may be behind this.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HD designed the study, worked on the analysis, and wrote the paper. HP helped design the study and assisted with the writing of the paper. VS helped design the study and assisted with the writing of the paper. AS assisted with advice in interpreting results and the writing of the paper. CK assisted with advice on interpreting results and the writing of the paper. CB helped with analysis, biostatistical support and the writing of the paper. CT helped design the study, led the analysis and also assisted with the writing of the paper, in particular the method. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: In total, $10 000 was contributed by EXPO, University of Western Sydney for obtaining the data for this study.

Competing interests: Elham Baghestan, Consultant, MD, PhD, Haukeland University Hospital, The Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 5021 Bergen-Norway.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the NSW Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee, Protocol No.2010/12/291.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data are only available to those with ethics approval for specified studies.

References

- 1.Baghestan E, Irgens L, Bordahl PE, et al. Trends in risk factors for obstetric anal sphincter injuries in Norway. Obstet Gynecol 2012;116:25–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Groom KM, Paterson-Brown S. Can we improve on the diagnosis of third degree tears? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2002;101:19–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laine K, Gissler M, Pirhonen J. Changing incidence of anal sphincter tears in four Nordic countries through the last decades. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2009;146:71–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kettle C, Tohill S. Perineal care. Clin Evid 2008;09:1–17 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahlen H, Homer CSE, Cooke M, et al. Perineal outcomes and maternal comfort related to the application of perineal warm packs in the second stage of labor. A randomized controlled trial. Birth 2007;34:282–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernando RJ, Sultan AHH, Kettle C, et al. Methods of repair for obstetric anal sphincter injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(3):CD002866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Z, McNally L, Hilder L, et al. Australia's mothers and babies 2009. AIHW, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 8.RCOG The management of third- and fourth-degree perineal tears. Green-Top Guideline 2007;29:11 [Google Scholar]

- 9.NSW Health New South Wales mothers and babies 2006. In: NSW Department of Health 2009, 20(S-1) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheer I, Andrews V, Thakar R, et al. Urinary incontinence after obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS)—is there a relationship? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2008;19:179–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samarasekera DN, Bekhit MT, Wright Y, et al. Long-term anal continence and quality of life following postpartum anal sphincter injury. Colorectal Dis 2008;10:793–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haadem K, Ohrlander S, Lingman G. Long-term ailments due to anal sphincter rupture caused by delivery—a hidden problem. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1988;27:27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Priddis H, Dahlen HG, Schmied V. Women's experiences following severe perineal trauma: a meta-ethnographic synthesis. J Adv Nurs 2013;64:748–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kudish B, Sokol RJ, Kruger M. Trends in major modifiable risk factors for severe perineal trauma, 1996–2006. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2008;102:165–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahlen H, Homer C. Perineal trauma and postpartum perineal morbidity in Asian and non-Asian primiparous women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2008;37:455–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kettle C, Tohill S. Perineal Care. Clin Evid 2008;09:1–17 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eskandar O, Shet D. Risk factors for 3rd and 4th degree perineal tear. J Obstet Gynaecol 2009;29:119–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Mahony F, Hofmeyr GJ, Menon V. Choice of instruments for assisted vaginal delivery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;11:CD005455 doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005455.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartman K, Viswanathan M, Palmieri R, et al. Outcomes of routine episiotomy: a systematic review. JAMA 2005;293:2141–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gottvall K, Allebeck P, Ekeus C. Risk factors for anal sphincter tears: the importance of maternal position at birth. BJOG 2007;114:1266–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts C, Bell J, Ford J, et al. Monitoring the quality of maternity care: how well are labour and delivery events reported in population health data? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2008;23:144–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor L, Travis S, Pym M, et al. How useful are hospital morbidity data for monitoring conditions occurring in the perinatal period? Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2005;45:36–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yudkin PL, Aboualfa JA, Eyre JA, et al. New birthweight and head circumference centiles for gestational ages 24 to 42 weeks. Early Hum Dev 1986;15:45–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patumanond J, Tawichasri C, Khunpradit S. Infant male sex as a risk factor for shoulder dystocia but not for cephalopelvic disproportion: an independent or confounded effect? Gend Med 2010;7:55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verspyck E, Goffiner F, Hellot MF, et al. Newborn shoulder width: a prospective study of 2222 consecutive measurements. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1999;106:589–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geary MP, Pringle PJ, Rodeck CH, et al. Sexual dimorphism in the growth hormone and insulinlike growth factor axis at birth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:3708–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carrascosa A, Yeste D, Copil A, et al. Anthropometric growth patterns of preterm and full-term newborns (24–42 weeks’ gestational age) at the Hospital Materno-Infantil Vall d'Hebron (Barcelona) (1997– 2002). An Pediatr (Barc) 2004;60:406–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dubrova IuE, Malinina TV, Suskov II, et al. Comparative analysis of variability in a complex of anthropometric traits in full-term and premature neonates. Genetika 1995;31:415–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guihard-Costa AM, Grangé G, Larroche JC, et al. Sexual differences in anthropometric measurements in French newborns. Biol Neonate 1997;72:156–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zatorska M. Values of somatic traits and of body proportion indices in boy and fe boy newborns of Lublin. Stud Hum Ecol 1992;10:75–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guihard-Costa AM, Papiernik E, Grangé G, et al. Gender differences in neonatal subcutaneous fat store in late gestation in relation to maternal weight gain. Ann Hum Biol 2002;29:26–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zaren B, Lindmark G, Bakketeig L. Maternal smoking affects fetal growth more in male the fetus. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2000;14:118–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Priddis H, Dahlen HG, Schmied V, et al. Risk of recurrence, subsequent mode of birth and morbidity for women who experienced severe perineal trauma in a first birth in New South Wales between 2000-2008: a population based data linkage study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13, doi:10.1186/1471-2393-1113-1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Engel S, Janevic T, S C, et al. Maternal smoking, preeclampsia, and infant health outcomes in New York City, 1995–2003′. Am J Epidemiol 2009;169:33–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Melamed N, Yogev Y, Glezerman M. Fetal gender and pregnancy outcome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2010;23:338–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheiner E, Levy A, Katz M, et al. Gender does matter in perinatal medicine. Fetal Diagn Ther 2004;19:366–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lurie S, Weissler A, Baider C, et al. Male fetuses and the risk of cesarean delivery. J Reprod Med 2004;49:353–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robson SJ, Laws P, Sullivan EA. Adverse outcomes of labour in public and private hospitals in Australia: a population based descriptive study. Med J Aust 2009;190:474–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tracy S, Welsh A, Dahlen H, et al. Letter to the Editor re Robson SJ, Laws P, Sullivan EA. Adverse outcomes of labour in public and private hospitals in Australia: a population-based descriptive study. Med J Aust 2009;190:474–7 191(10):579–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dahlen H, Ryan M, Homer C, et al. An Australian prospective cohort study of risk factors for severe perineal trauma during childbirth. Midwifery 2007;23:196–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andrews V, Sultan AH, Thakar R, et al. Risk Factors for Obstetric Anal Sphincter Injury: A Prospective Study. Birth 2006;33:117–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN. Pudendal nerve damage during labour: prospective study before and after childbirth. BJOG 1994;101:22–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sassi F, Devaux M, Cecchini M, et al. The obesity epidemic: analysis of past and projected future trends in selected OECD countries. OECD Health Working Papers: OECD Publishing, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Australia's Health 2004. Canberra: AIHW [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.