Abstract

Objectives

Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC) and Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) can facilitate transmission of HIV. Men who have sex with men (MSM) may harbour infections at genital and extragenital sites. Data regarding extragenital GC and CT infections in military populations are lacking. We examined the prevalence and factors associated with asymptomatic GC and CT infection among this category of HIV-infected military personnel.

Design

Cross-sectional cohort study (pilot).

Setting

Infectious diseases clinic at a single military treatment facility in San Diego, CA.

Participants

Ninety-nine HIV-positive men were evaluated—79% men who had sex with men, mean age 31 years, 36% black and 33% married. Inclusion criteria: male, HIV-infected, Department of Defense beneficiary. Exclusion criteria: any symptom related to the urethra, pharynx or rectum.

Primary outcome measures

GC and CT screening results.

Results

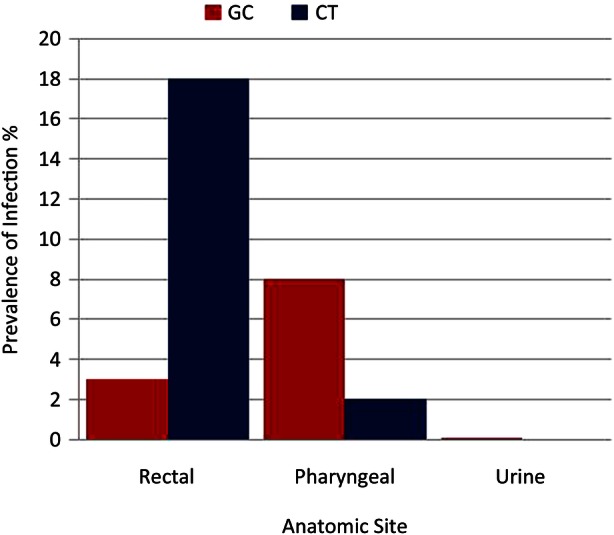

Twenty-four per cent were infected with either GC or CT. Rectal swabs were positive in 18% for CT and 3% for GC; pharynx swabs were positive in 8% for GC and 2% for CT. Only one infection was detected in the urine (GC). Anal sex (p=0.04), male partner (OR 7.02, p=0.04) and sex at least once weekly (OR 3.28, p=0.04) were associated with infection. Associated demographics included age <35 years (OR 6.27, p=0.02), non-Caucasian ethnicity (p=0.03), <3 years since HIV diagnosis (OR 2.75, p=0.04) and previous sexually transmitted infection (STI) (OR 5.10, p=0.001).

Conclusions

We found a high prevalence of extragenital GC/CT infection among HIV-infected military men. Only one infection was detected in the urine, signalling the need for aggressive three-site screening of MSM. Clinicians should be aware of the high prevalence in order to enhance health through comprehensive STI screening practices.

Keywords: gonorrhea, chlamydia, DADT, MSM

Article summary.

Article focus

Is asymptomatic gonorrhoea and chlamydia infection prevalent among US military men with HIV?

If so, are those infections associated with any specific sexual practice or relationship beliefs?

Key messages

Men who have sex with men (MSM) in the US military are at risk for asymptomatic gonorrhoea and chlamydia infection, predominantly at extragenital sites.

Sex with men, anal sex, non-Caucasian ethnicity, age <35 years and HIV infection for <3 years were all associated with asymptomatic infection.

Repeal of ‘don't ask, don't tell’ fostered a change in the US military medical culture, allowing clinicians to counsel and screen MSM according to established guidelines.

Strengths and limitations of this study

First comprehensive data set of asymptomatic gonorrhoea/chlamydia infection in a male US military population previously infected with HIV.

First study to describe the health needs of men who have sex with men in a US military population.

Observational study.

Small n (pilot study).

Inability to obtain three-site anatomic screening from all participants.

Introduction

Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC) and Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) may cause infection in the male urethral, pharyngeal and rectal mucosa, thus facilitating transmission of the HIV.1–3 Men who have sex with men (MSM) are at particular risk for harbouring these infections at extragenital sites.4–10 The institution of the US law, ‘don't ask, don't tell’ (DADT), allowed gay persons to serve in the military but made it unlawful for a service member to reveal his/her sexual orientation. Until its repeal in 2011, nearly 14 000 qualified service members were separated from the military.11 Although there are several published reports regarding GC/CT infections in MSM, limited data existed among US military members.7 9 10 12–15 Since 1986, the US military maintains a natural history study of HIV-infected persons receiving military healthcare and reports of GC/CT infection status in this cohort have been published.16 Several other reports document GC/CT infections in the US military men.17–24 However, owing to the DADT policy, these reports could not represent the full spectrum of GC/CT infection in a military MSM population because they only included data from the urine/urethra specimens. Presently, extragenital anatomic site data and comprehensive sexual practices and behaviours may now be reported.

The Naval Medical Center San Diego (NMCSD) is one of three US Navy HIV Evaluation and Treatment Units that provides healthcare to approximately 575 HIV-infected Department of Defense beneficiaries, approximately half of whom are currently serving on active military duty. Services offered include comprehensive primary and subspecialty healthcare, mental health services, prevention counselling and health promotion, as well as HIV and other sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening and management.25 However, three-anatomic site GC/CT screening was not routinely performed in any US Navy medical treatment facility prior to this study.

Given the lack of data on asymptomatic GC and CT infection among a US military cohort of HIV-infected men, we conducted a cross-sectional pilot study with the objectives (1) to describe the prevalence of asymptomatic urethral, pharyngeal and rectal GC/CT infection in this population; (2) to identify specific sexual behaviours, relationship attitudes and HIV disease attributes among this cohort and (3) to determine specific factors associated with asymptomatic GC/CT infections.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedures

All HIV-infected US Navy and Marine Corps members serving on active duty are required to participate in a biannual medical and psychosocial evaluation. Those serving at military bases in the western US and Pacific Basin report to NMCSD for these visits. Beginning in September 2010, we presented the study to each consecutive military member presenting for required HIV evaluation until we enrolled 100 participants. The study was designed as a pilot study to guide the design of future research. No incentive to participate was offered. Those who participated did so to optimise personal sexual health through more thorough STI screening. Inclusion criteria included: male gender, HIV-infected, receiving care at the NMCSD and having no current symptoms referable to the pharynx, urethra or rectum on the day of enrolment. Study participants completed a short questionnaire regarding sexual practices and relationship attitudes. In order to encourage honest responses, the written questionnaire was administered by the clinic's non-military preventive medicine counsellor and all responses were confidentially maintained.

Each participant was screened for asymptomatic GC/CT infection of the urethra, pharynx and rectum using a first-void urine sample and posterior pharyngeal and rectal swabs obtained by their primary HIV provider during their routine, biannual HIV clinic visit. All collected specimens were collected on the day the questionnaire was completed and any infections were appropriately treated. The NMCSD laboratory previously validated the APTIMA Combo2 Assay (Gen-Probe Inc., San Diego, California, USA) for testing the pharyngeal and rectal specimens according to Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) standard Sec 493.1253. Medical records were reviewed by an HIV clinician and data regarding demographics, prior STIs and HIV-related data were collected. This study was previously approved with a waiver of informed consent granted by the NMCSD Institutional Review Board.

Data analysis

The data collected (laboratory results, questionnaire responses and medical record information) were entered into a Microsoft Excel 2003 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA) database and analysed with SAS V.9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Prevalence rates were calculated for each type of infection (GC, CT or both) at each site. The descriptive statistics included for categorical variables were counts and proportions, compared with means and standard deviations for continuous variables. χ² or Fisher's exact tests were performed, as appropriate, to analyse the bivariate relationships between the factors of interest and the outcome defined as being positive for either infection (GC and/or CT in at least one site). OR, 95% CI and p values were reported. p Values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

One hundred and six consecutive patients were offered participation in the study before one hundred were enrolled. One participant was later excluded owing to recent treatment of an asymptomatic rectal CT infection prior to enrolment. Owing to scheduling conflicts and technical difficulties, only 96 urine specimens and 87 rectal/pharyngeal swabs were actually tested. The cohort (n=99) included 79% who were MSM. The mean age of the cohort was 31 years, and race was reported as black in 36%, Caucasian in 35%, Hispanic in 15% and other in 13%. Sixty-seven per cent were unmarried, and 36% had a previous history of STI. HIV-related characteristics included a mean CD4 count of 609 cells/mm3; 43% had an HIV viral load <48 copies/µl, 51% were receiving antiretroviral therapy and the mean time since HIV diagnosis was 63 months (table 1).

Table 1.

HIV-infected male demographic characteristics, 2011—San Diego, California, USA (n=99)

| HIV variables | |

| CD4 count mean (SD), cells/mm3 | 609 (216) |

| Suppressed HIV VL (<48 copies/µl) | 43% |

| Receiving ART | 51% |

| Time since HIV diagnosis mean (SD), months | 62.8 (59.9) |

| Demographic variables | |

| Age | |

| Mean (SD), years | 30.9 (8.2) |

| <25 years | 28% |

| 25–34 years | 38% |

| ≥35 years | 33% |

| Ethnicity | |

| Black | 36% |

| Caucasian | 35% |

| Hispanic | 15% |

| Other | 13% |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 33% |

| Single | 67% |

| Sexual practice | |

| MSM | 79% |

| MSW | 21% |

| Previous STI | |

| Yes | 36% |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; CD4, helper T cell count; MSM, men who have sex with men; MSW, men who have sex with women; STI, sexually transmitted infection; VL, plasma viral load.

Twenty-four per cent of the participants had either GC or CT infection in at least one site. The rectal swab yielded the highest prevalence (18.4%), followed by the pharynx (9.2%) and the urethra (1%). Of the rectal swabs, 18% were positive for CT and 3% for GC while of the pharynx swabs, 8% were positive for GC and 2% for CT. Only one infection was detected in a urine specimen (GC) (table 2). Eighty-one per cent of the identified infections tested positive at only one site, 19% were positive at two anatomic sites and none were positive at all three sites.

Table 2.

Prevalence of asymptomatic infection by anatomic site, HIV-infected men, 2011—San Diego, California, USA (n=99)*

| Either infection |

CT |

GC |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | n | Prevalence rate (%) | Cases | n | Prevalence rate (%) | Cases | n | Prevalence rate (%) | |

| Overall | 20 | 83 | 24.1 | 17 | 83 | 20.5 | 8 | 83 | 9.6 |

| Urethra | 1 | 96 | 1.0 | 0 | 96 | 0.0 | 1 | 96 | 1.0 |

| Rectum | 16 | 87 | 18.4 | 16 | 87 | 18.4 | 3 | 87 | 3.4 |

| Pharynx | 8 | 87 | 9.2 | 2 | 87 | 2.3 | 7 | 87 | 8.0 |

*Some participants did not have screening at all three sites.

Using bivariate analysis, anal sex (p=0.04), having a male partner (OR 7.02, p=0.04) and having sex at least once weekly (OR 3.28, p=0.04) were associated with infection; vaginal sex was protective (OR 0.20, p=0.03). Demographic factors associated with infection included age <35 years (OR 6.27, p=0.02), non-Caucasian ethnicity (black OR 5.50, p=0.04; Hispanic OR 11.00, p=0.01; other race OR 7.33, p=0.03), <3 years since HIV diagnosis (OR 2.75, p=0.04) and previous STI (OR 5.10, p=0.001; tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Survey responses—demographic and sexual practices by infection status, HIV-infected men, 2011—San Diego, California, USA

| Total |

CT and/or GC infection |

Neither infection |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | OR | 95% CI | p Value* | |

| Demographic variables (n respondents) | |||||||||

| Gender of sexual partner(s) (n=98) | – | ||||||||

| Women only | 21 | (21.4) | 1 | (4.8) | 20 | (26.0) | REF | 1.88 to 55.72 | – |

| Male (MSM) | 77 | (78.6) | 20 | (95.2) | 57 | (74.0) | 7.02 | 0.04 | |

| Race/ethnicity (n=99) | 0.03 | ||||||||

| White | 35 | (35.4) | 2 | (9.5) | 33 | (42.3) | REF | – | |

| Black | 36 | (36.4) | 9 | (42.9) | 27 | (34.7) | 5.50 | 1.10 to 27.64 | 0.04 |

| Hispanic | 15 | (15.2) | 6 | (28.6) | 9 | (11.5) | 11.00 | 1.89 to 64.06 | 0.01 |

| Other | 13 | (13.0) | 4 | (19.0) | 9 | (11.5) | 7.33 | 1.15 to 46.66 | 0.03 |

| Age (n=99) | |||||||||

| <35 years | 66 | (66.7) | 19 | (90.5) | 47 | (60.3) | 6.27 | 1.36 to 28.82 | 0.02 |

| ≥35 years | 33 | (33.3) | 2 | (9.5) | 31 | (39.7) | REF | – | – |

| Previous history of STI (n=99) | |||||||||

| No | 63 | (63.6) | 7 | (33.3) | 56 | (71.8) | REF | – | – |

| Yes | 36 | (36.4) | 14 | (66.7) | 22 | (28.2) | 5.10 | 1.81 to 14.30 | 0.001 |

| Number of years since HIV diagnosis (n=99) | |||||||||

| >3 years | 57 | (57.6) | 8 | (38.1) | 49 | (62.8) | REF | – | – |

| ≤3 years | 42 | (42.4) | 13 | (61.9) | 29 | (37.2) | 2.75 | 1.02 to 7.41 | 0.04 |

| Sexual practices (n respondents) | |||||||||

| Vaginal sex (n=99) | |||||||||

| No | 70 | (70.7) | 19 | (90.5) | 51 | (65.4) | REF | – | – |

| Yes | 29 | (29.3) | 2 | (9.5) | 27 | (34.6) | 0.20 | 0.04 to 0.92 | 0.03 |

| Oral sex† (n=99) | |||||||||

| No | 3 | (3.0) | 0 | (0) | 3 | (3.8) | REF | – | – |

| Yes | 96 | (97.0) | 21 | (100) | 75 | (96.2) | – | – | 1.00 |

| Anal sex† (n=99) | |||||||||

| No | 15 | (15.2) | 0 | (0) | 15 | (19.2) | REF | – | – |

| Yes | 84 | (84.8) | 21 | (100) | 63 | (80.8) | – | – | 0.04 |

| Insertive anal sex (n=80) | |||||||||

| No | 15 | (18.8) | 5 | (23.8) | 10 | (16.9) | 1.00 | – | – |

| Yes | 65 | (81.2) | 16 | (76.2) | 49 | (83.1) | 0.65 | 0.19 to 2.20 | 0.52 |

| Receptive anal sex (n=80) | – | ||||||||

| No | 17 | (21.3) | 2 | (9.5) | 15 | (25.4) | REF | 0.67 to 15.57 | – |

| Yes | 63 | (78.7) | 19 | (90.5) | 44 | (74.6) | 3.32 | 0.21 | |

*Fisher's exact test was performed for variables with expected cell frequencies <5; otherwise, a χ² test was performed.

†OR and 95% CI not available owing to one or more zero cells.

MSM, men who have sex with men (self-reported).

Oral and oral–anal sex were not significantly associated with infection with p>0.05.

Table 4.

Survey responses—relationship attitudes and condom use by infection status, HIV-infected men, 2011—San Diego, California

| Total |

CT and/or GC Infection |

Neither infection |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | OR | 95% CI | p Value* | |

| Relationship attitudes (n respondents) | |||||||||

| Sexual relationships with >1 partner in the past year (n=99) | |||||||||

| No | 39 | (39.4) | 5 | (23.8) | 34 | (43.6) | REF | – | – |

| Yes | 60 | (60.6) | 16 | (76.2) | 44 | (56.4) | 2.47 | 0.82 to 7.42 | 0.10 |

| Frequency of sexual activity in the past year (n=99) | |||||||||

| <Once a week | 38 | (38.4) | 4 | (19.0) | 34 | (43.6) | REF | – | – |

| At least once a week | 61 | (61.6) | 17 | (81.0) | 44 | (56.4) | 3.28 | 1.01 to 10.66 | 0.04 |

| Sexual relations only with partner in a serious relationship (n=99) | 0.14 | ||||||||

| Strongly agree | 51 | (51.5) | 7 | (33.3) | 44 | (56.4) | REF | – | – |

| Neither agree/disagree | 20 | (20.2) | 5 | (23.8) | 15 | (19.2) | 2.10 | 0.59 to 7.60 | 0.26 |

| Strongly disagree | 28 | (28.3) | 9 | (42.9) | 19 | (24.4) | 2.98 | 0.97 to 9.17 | 0.06 |

| Expect monogamy in a serious relationship (n=99) | 0.48 | ||||||||

| Strongly agree | 75 | (75.8) | 14 | (66.7) | 61 | (78.1) | REF | – | – |

| Neither agree/disagree | 10 | (10.1) | 3 | (14.3) | 7 | (9.0) | 1.87 | 0.43 to 8.14 | 0.41 |

| Strongly disagree | 14 | (14.1) | 4 | (19.0) | 10 | (12.9) | 1.74 | 0.48 to 6.38 | 0.40 |

| Sexual activities mostly with casual friends (n=99) | 0.08 | ||||||||

| Strongly disagree | 52 | (53.0) | 8 | (38.0) | 44 | (57.2) | REF | – | – |

| Neither agree/disagree | 24 | (24.5) | 9 | (43.0) | 15 | (19.5) | 3.30 | 1.08 to 10.10 | 0.04 |

| Strongly agree | 22 | (22.5) | 4 | (19.0) | 18 | (23.3) | 1.22 | 0.33 to 4.57 | 0.77 |

| Condom use (n respondents) | |||||||||

| Self-condom use during oral sex (n=92) | |||||||||

| Always | 12 | (13.0) | 4 | (20.0) | 8 | (11.1) | REF | – | – |

| Do not always | 80 | (87.0) | 16 | (80.0) | 64 | (88.9) | 0.50 | 0.13 to 1.87 | 0.29 |

| Partner-condom use during oral sex (n=90) | |||||||||

| Always | 13 | (14.4) | 4 | (19.0) | 9 | (13.0) | REF | – | – |

| Do not always | 77 | (85.6) | 17 | (81.0) | 60 | (87.0) | 0.64 | 0.17 to 2.34 | 0.49 |

| Self-condom use during anal sex (n=82) | |||||||||

| Always | 42 | (51.2) | 9 | (45.0) | 33 | (53.2) | REF | – | – |

| Do not always | 40 | (48.8) | 11 | (55.0) | 29 | (46.8) | 1.39 | 0.51 to 3.83 | 0.52 |

| Partner-condom use during anal sex (n=80) | |||||||||

| Always | 37 | (46.2) | 8 | (38.1) | 29 | (49.2) | REF | – | – |

| Do not always | 43 | (53.8) | 13 | (61.9) | 30 | (50.8) | 1.57 | 0.57 to 4.35 | 0.38 |

*Fisher's exact test was performed for variables with expected cell frequencies <5; otherwise, a χ² test was performed.

†OR and 95% CI not available owing to one or more zero cells.

CT, Chlamydia trachomatis; GC Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Only about half of the participants reported consistent use of condoms during anal sex, and less than half always required their partner to use condoms during anal sex. During oral sex, less than 15% of participants reported always using condoms and always requiring their partner to use condoms (table 4).

With regard to relationship attitudes, 52% of participants reported sexual relations only with a partner in a serious relationship, while 28% disagreed with this statement. Seventy-six per cent of participants expected monogamy in a serious relationship, while 14% disagreed with this statement. Twenty-three per cent of participants participated in most of their sexual relations with casual friends, while 53% disagreed with this statement. None of these beliefs were significantly associated with infection (table 4).

Figure 1.

Distribution of asymptomatic gonococcal (GC) and chlamydial (CT) prevalence among HIV-infected men, San Diego, California, 2011.

Discussion

We found an alarming prevalence of GC/CT infection—nearly twice that of non-military MSM in other large California cities.10 In fact, this may represent an underestimate, since some of our patients very likely sought screening (and subsequent therapy) at the local county STD clinic prior to their military encounter, owing to the fear of discipline or discharge.26 27 We believe that there are two important contributors to the high prevalence rates observed—DADT and the first-screen effect.

DADT very likely contributed the most to undiagnosed infection. The American Medical Association posited that this military law compromised the medical care of gay patients serving in the military.28 Prior to repeal, military healthcare providers often believed they could not ask, document or counsel about sexual behaviours or orientations for fear of revealing MSM practices of their patients that could lead to adverse legal action for the service member. Therefore, all potential risks would not have been assessed such that screening all three anatomic sites did not occur. DADT very likely prevented patients from providing honest answers or reports of sexual practices, for fear of adverse legal action. We started our study prior to the repeal because SECNAVINST 5300.30D (the document that governs the management of HIV infection in the Navy and Marine Corps) offered protection against adverse action related to information obtained from a medical or epidemiological interview. Unfortunately, this provision was not well known to military healthcare providers.

Second, our study facilitated the initiation of sexual risk-driven screening for GC/CT infection in our healthcare facility. Hence, study data represent the first time most participants were screened for extragenital GC/CT infection. First-time screening for a condition may reveal more prevalent cases than subsequent screening, especially in the case of asymptomatic infection, and may partially explain why we detected a higher prevalence than that found in other California cities, which may represent subsequent screening data.

Our study also had several important findings regarding HIV-positive men serving in the US military. With regard to sexual practices, most respondents were MSM and engaged in oral, anal (receptive and insertive) and oral–anal sex. As expected, most respondents do not use condoms during oral sex, but surprisingly, nearly half of the respondents do not always use condoms or require their partners to use condoms during anal sex either. Potential contributors to the low reported rates of condom use include safer sex fatigue, serosorting and seropositioning.29 Regarding relationship attitudes, about half of the respondents believe sexual relations should only occur with partners in a serious relationship, while approximately one-quarter engage in sex with casual friends. When in a serious relationship, the majority of respondents expect monogamy.

Our study results identified MSM, anal sex, non-Caucasian ethnicity and younger age to be more associated with GC/CT infections thus recognised as STI risk factors, in agreement with other studies.16 30–32 Generally, those patients with a recently acquired HIV infection or prior history of STI have a higher risk for GC/CT infection. The increased risk among non-Caucasians may be related to cultural or societal stigma, which may prevent an individual from seeking screening services (and need to disclose self-perceived taboo sexual behaviour) in a way that DADT very likely prevented military MSM from seeking or receiving appropriate screening.

We acknowledge the potential limitations of our study—those inherent to an observational design, inability to achieve 100% three-site screening from all participants and a small study population. Although our sample size is small, it is worth noting that trends in our data are similar to trends noted in larger non-military studies of GC/CT infection: most infections were detected at extragenital sites; the majority of rectal infections were related to CT, and the majority of pharyngeal infections were related to GC. Finally, although there may have been some reluctance on the part of participants to answer survey questions honestly, we believe this was minimised by our confidential survey procedures and as reflected by the candid responses we did receive.

This is the first comprehensive data set of asymptomatic GC/CT infection in a male HIV-positive US military population. Along with the CDC's recommendations, these results underscore the need for military healthcare providers to screen their MSM population for infection at all three anatomic sites. Just as noted in larger studies, we confirm that urine/urethral screening alone may fail to detect many asymptomatic infections in the MSM population. Finally, the low rates of reported condom use among HIV-positive participants signal the need to enhance safer sex prevention efforts among MSM.

We hope to use the results of this study to help design and complete larger, multisite STI clinical trials for the US military. We can conclude that MSM make up a significant proportion of our HIV-infected population. Now that DADT has been repealed and the Department of Defense has mandated the extension of military benefits to same sex partners,33 we should look to modify the treatment guidelines for MSM in our military to enhance overall health.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: RJC contributed to the conception and design, acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of data, participated in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and was involved in the final approval of the version to be published. ONR, NA, KPOB, MDJ, HLG, RCM, MFB and NFCC contributed to the acquisition of data, participated in the drafting of the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and were involved in final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the US Government.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: IRB, Naval Medical Center San Diego.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Cohen MS, Hoffman IF, Royce RA, et al. Reduction of concentration of HIV-1 in semen after treatment of urethritis: implications for prevention of sexual transmission of HIV-1. AIDSCAP Malawi Research Group. Lancet 1997;349:1868–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galvin SR, Cohen MS. The role of sexually transmitted diseases in HIV transmission. Nature reviews. Microbiology 2004;2:33–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vernazza PL, Eron JJ, Fiscus SA, et al. Sexual transmission of HIV: infectiousness and prevention. AIDS 1999;13:155–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Workowski KA, Berman S. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 2010;59:1–110 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park J, Marcus JL, Pandori M, et al. Sentinel surveillance for pharyngeal Chlamydia and gonorrhea among men who have sex with men—San Francisco, 2010. Sex Transm Dis 2012;39:482–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoover KW, Butler M, Workowski K, et al. STD screening of HIV-infected MSM in HIV clinics. Sex Transm Dis 2010;37:771–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schachter J, Moncada J, Liska S, et al. Nucleic acid amplification tests in the diagnosis of chlamydial and gonococcal infections of the oropharynx and rectum in men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2008;35:637–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rieg G, Lewis RJ, Miller LG, et al. Asymptomatic sexually transmitted infections in HIV-infected men who have sex with men: prevalence, incidence, predictors, and screening strategies. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2008;22:947–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geisler WM, Whittington WL, Suchland RJ, et al. Epidemiology of anorectal chlamydial and gonococcal infections among men having sex with men in Seattle: utilizing serovar and auxotype strain typing. Sex Trans Dis 2002;29:189–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kent CK, Chaw JK, Wong W, et al. Prevalence of rectal, urethral, and pharyngeal chlamydia and gonorrhea detected in 2 clinical settings among men who have sex with men: San Francisco, California, 2003. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burrelli DF. ‘Don't Ask, Don't Tell’: The Law and Military Policy on Same-Sex Behavior. Secondary ‘Don't Ask, Don't Tell’: The Law and Military Policy on Same-Sex Behavior 2010. http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R40782.pdf (accessed 15 Mar 2013).

- 12.Miller WC, Zenilman JM. Epidemiology of chlamydial infection, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis in the United States—2005. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2005;19:281–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mimiaga MJ, Helms DJ, Reisner SL, et al. Gonococcal, chlamydia, and syphilis infection positivity among MSM attending a large primary care clinic, Boston, 2003 to 2004. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36:507–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phipps W, Stanley H, Kohn R, et al. Syphilis, Chlamydia, and gonorrhea screening in HIV-infected patients in primary care, San Francisco, California, 2003. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2005;19:495–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rietmeijer CA, Patnaik JL, Judson FN, et al. Increases in gonorrhea and sexual risk behaviors among men who have sex with men: a 12-year trend analysis at the Denver Metro Health Clinic. Sex Transm Dis 2003;30:562–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spaulding AB, Lifson AR, Iverson ER, et al. Gonorrhoea or Chlamydia in a U.S. military HIV-positive cohort. Sex Trans Infect 2012;88:266–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aldous WK, Robertson JL, Robinson BJ, et al. Rates of gonorrhea and Chlamydia in U.S. military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan (2004–2009). Mil Med 2011;176:705–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brodine SK, Shafer MA, Shaffer RA, et al. Asymptomatic sexually transmitted disease prevalence in four military populations: application of DNA amplification assays for Chlamydia and gonorrhea screening. J Infect Dis 1998;178:1202–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sena AC, Miller WC, Hoffman IF, et al. Trends of gonorrhea and chlamydial infection during 1985–1996 among active-duty soldiers at a United States Army installation. Clin Infect Dis 2000;30:742–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cecil JA, Howell MR, Tawes JJ, et al. Features of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection in male Army recruits. J Infect Dis 2001;184:1216–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zenilman JM, Glass G, Shields T, et al. Geographic epidemiology of gonorrhoea and Chlamydia on a large military installation: application of a GIS system. Sex Trans Infect 2002;78:40–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shafer MA, Boyer CB, Shaffer RA, et al. Correlates of sexually transmitted diseases in a young male deployed military population. Mil Med 2002;167:496–500 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arcari CM, Gaydos JC, Howell MR, et al. Feasibility and short-term impact of linked education and urine screening interventions for Chlamydia and gonorrhea in male army recruits. Sex Trans Dis 2004;31:443–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood BJ, Gaydos JC, McKee KT, Jr, et al. Comparison of the urine Leukocyte Esterase Test to a Nucleic Acid Amplification Test for screening non-health care-seeking male soldiers for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections. Mil Med 2007;172:770–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crum NF, Grillo M, Wallace MR. HIV care in the U.S. Navy: a multidisciplinary approach. Mil Med 2005;170:1019–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katz KA. Health hazards of ‘don't ask, don't tell’. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2380–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith DM. Active duty military personnel presenting for care at a Gay Men's Health Clinic. J Homosex 2008;54:277–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Reilly KB. AMA meeting: ‘Don't ask, don't tell’ said to hurt patient care; repeal urged. Secondary AMA meeting: ‘Don't ask, don't tell’ said to hurt patient care; repeal urged 2009. http://www.ama-assn.org/amednews/2009/11/23/prsc1123.htm (accessed 15 Mar 2013).

- 29.McFarland W, Chen YH, Nguyen B, et al. Behavior, intention or chance? A longitudinal study of HIV seroadaptive behaviors, abstinence and condom use. AIDS Behav 2012;16:121–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mustanski BS, Newcomb ME, Du Bois SN, et al. HIV in young men who have sex with men: a review of epidemiology, risk and protective factors, and interventions. J Sex Res 2011;48:218–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newman LM, Berman SM. Epidemiology of STD disparities in African American communities. Sex Trans Dis 2008;35(12 Suppl):S4–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolitski RJ, Fenton KA. Sexual health, HIV, and sexually transmitted infections among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in the United States. AIDS Behav 2011;15(Suppl 1):S9–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panetta L. Memorandum for Secretaries of the Military Departments Acting Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness. Secondary Memorandum for Secretaries of the Military Departments Acting Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness 2013. http://www.defense.gov/news/Same-SexBenefitsMemo.pdf (accessed 15 Mar 2013).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.