Abstract

Objectives

Early childhood caries is a highly destructive dental disease which is compounded by the need for young children to be treated under general anaesthesia. In Australia, there are long waiting periods for treatment at public hospitals. In this paper, we examined the costs and patient outcomes of a prevention programme for early childhood caries to assess its value for government services.

Design

Cost-effectiveness analysis using a Markov model.

Setting

Public dental patients in a low socioeconomic, socially disadvantaged area in the State of Queensland, Australia.

Participants

Children aged 6 months to 6 years received either a telephone prevention programme or usual care.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

A mathematical model was used to assess caries incidence and public dental treatment costs for a cohort of children. Healthcare costs, treatment probabilities and caries incidence were modelled from 6 months to 6 years of age based on trial data from mothers and their children who received either a telephone prevention programme or usual care. Sensitivity analyses were used to assess the robustness of the findings to uncertainty in the model estimates.

Results

By age 6 years, the telephone intervention programme had prevented an estimated 43 carious teeth and saved £69 984 in healthcare costs per 100 children. The results were sensitive to the cost of general anaesthesia (cost-savings range £36 043–£97 298) and the incidence of caries in the prevention group (cost-savings range £59 496–£83 368) and usual care (cost-savings range £46 833–£93 328), but there were cost savings in all scenarios.

Conclusions

A telephone intervention that aims to prevent early childhood caries is likely to generate considerable and immediate patient benefits and cost savings to the public dental health service in disadvantaged communities.

Keywords: Health Economics, Preventive Medicine

Article summary.

Article focus

This paper reports on the costs and patient outcomes of a caries prevention programme.

Key messages

A telephone prevention programme provides significant cost savings to the health system.

The main cost savings are due to the significantly lower caries incidence in the prevention programme and the avoided high costs of treatment.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first economic analysis for early childhood caries prevention in Australia and one of the few worldwide.

Our analysis did not include quality-of-life data or out-of-pocket costs and potential income losses for families. The savings would have been even better if these costs had been included in the analysis.

Introduction

Early childhood caries (ECC) is a significant problem in low socioeconomic populations.1,2 It is the most common cause of toothache, oral abscesses and preventable hospital admissions in young children.3 The cost of dental treatment in young children is high due to the severity of the caries, the requirement for aggressive treatment, and the need for general anaesthesia or sedation.4–6 Even when extensive restorative and surgical treatment is provided, the success of rehabilitation is low. Children who receive treatment under general anaesthesia frequently require further hospitalisation for new lesions, some as soon as 6 months after the first general anaesthesia.7 8 The long-term costs of ECC are compounded by higher caries rates in later childhood and adulthood.7–9

The costs of general anaesthetics are dependent on the country and treatment needs, but have been reported to be approximately US$2000.10 This is broadly in agreement with Queensland public hospital data, which have average costs between £810–£2430 per child.11 12 The costs of ECC are not limited to treatment and hospitalisation costs. There are high social costs associated with poor dentition, and a diminished quality of life due to pain and discomfort especially because of the long waiting lists for treatment. Social costs include lack of sleep, lost time for school, behavioural problems, lack of cooperation and diminished learning.3 13 Lost working time for parents accompanying children to dental treatment sessions has been reported to lead to loss of employment.14 Studies in this area need to appreciate the full impact of ECC on the child, family and society.15

To date, the reported economic burden of ECC is likely to be underestimated, as previous estimates did not capture the full scope of costs and missed the potential cost savings of prevention programmes. There are few studies involving child populations that evaluate the cost-effectiveness of prevention programmes for ECC.16 17 Savage et al18 concluded that preschool-aged children in the USA who had early dental prevention visits would experience lower dental-related costs over 5 years. Similarly, a second US study by Ramos-Gomez and Shepard19 looked at minimal, intermediate and comprehensive prevention programmes and concluded that all three were cost-effective. They concluded that government health systems can save considerable resources by investing in ECC prevention. A study by Lee et al5 in Carolina, USA, found that early dental visits were highly cost-effective for high-risk children. All the above studies reiterate the need for translating this evidence into policies for ECC prevention.

Although the cost savings of prevention programmes are based on predictions, the potential economic benefits are encouraging. A number of prevention programmes consistently report reductions in caries prevalence and carious surfaces.20–22 Our previous study showed that a telephone education programme, delivered 6 monthly from birth, significantly reduced incident caries in children by 2 years of age compared with children who did not receive the education programme.23 Our aim in this paper was to quantify the healthcare costs of delivering a telephone education programme and the potential cost savings through prevention of dental caries in children from a low socioeconomic, socially-disadvantaged area.

Methods

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from Queensland Health (No. 2006/145) and the University of Queensland (No. 2006000988). A signed informed consent was obtained from all mothers prior to initiation. The participants’ rights and responsibilities were discussed in relation to the participation, withdrawal of consent and confidentiality. In particular, the potential participants understood that their non-participation would not affect the dental care they received. Full details on the prevention programme recruitment and protocol are provided in the previous publication.23 In a birth cohort, mothers in the telephone intervention group were telephoned when their children were aged approximately 6, 12 and 18 months. Oral health education, including dietary advice and tooth brushing instruction, was given at each appointment. The mothers were instructed to brush their children's teeth twice daily with children's toothpaste as soon as the teeth emerged. Dietary advice included avoiding foods and drinks containing sugar, and encouraging the use of tooth-friendly snacks such as cheese. Telephone calls took an average of 15–20 min. Free toothbrushes and toothpastes were mailed to the mothers at the completion of each telephone call. A usual care group of children, approximately 2 years of age, that had no previous contact with the dental service was recruited from child care centres in the same district. The usual care group is indicative of the current model of care in government facilities and the prevalence of caries reported was consistent with other studies conducted in the same study area and similar socioeconomic populations.12

Mothers were recruited from public health birthing and birthing-related facilities in the Logan-Beaudesert area, one of the lowest socioeconomic areas in Queensland.24 Recruitment occurred by oral health personnel approaching all mothers presenting to these facilities and asking whether they would like to be involved in the prospective study. The study population's water supply was artificially fluoridated. At 2 years of age, all the children enrolled in the study attended the community (government funded) clinic for a dental examination. The examination was performed by examiners blinded to the study group. Dental lighting and a mouth mirror were used to examine for oral abnormalities and the number of teeth present. The teeth were dried using cotton rolls and checked for cavitations and white spot lesions of early caries.25

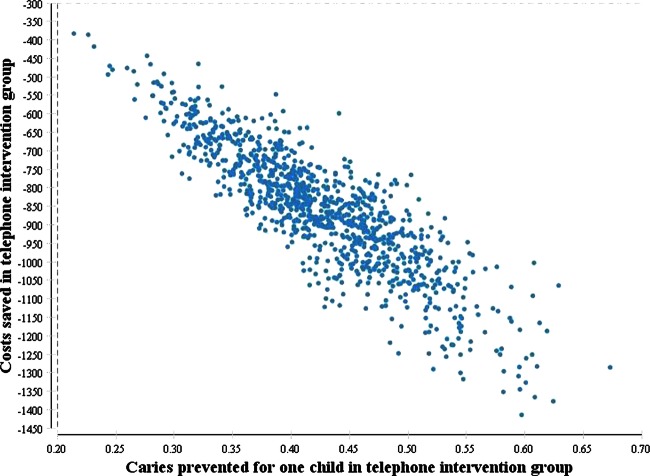

Markov model

A health state-transition Markov model26 was constructed in TreeAge Pro 2011 (TreeAge Software Inc, Williamstown, Massachusetts, USA) and designed to represent the paediatric oral health status of the district from a public health viewpoint (figure 1). This model examines the health and caries incidence of children who received the intervention versus usual care using data from two primary sources: the prevention programme results and the district service's clinical database. The model tracked a cohort for 11 cycles, each of 6 months duration, from ages 6 months to 6 years. The starting age of 6 months was selected because this is when the first teeth erupt, and the final age of 6 years because this is when the primary dentition enters the stage of mixed dentition. The model consisted of two key health states: ‘healthy’ and ‘caries’ (figure 1). All children started in the ‘healthy’ (or caries free) state as newly erupted teeth are not yet decayed. The children could move between these mutually exclusive states, once every 6 months, or remain in the same state. A child may wait longer than 6 months to be treated, but following treatment the child moves to the ‘healthy’ state. A child that develops caries and is subsequently treated may experience a repeat caries or remain caries free. By observing the movement of children through the states, the model can estimate the total healthcare costs and the incidence of caries. The caries incidence information was obtained for primary teeth and included all caries types: enamel, dentine and pulpal involvement.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the Markov model, used to estimate the costs and caries numbers in the telephone intervention and usual care groups. Clone 1: the structure of the usual care clone is identical to the telephone pathways, but with different probabilities of moving between states. ECC, early childhood caries; restoration, tooth restored within 6 months; restoration only, restoration without crown.

Data and sources

Costs

Costs for the telephone intervention programme included: staff time for the delivery of the telephone intervention (including unanswered telephone calls), telephone call costs, packing and posting oral care products, and other administrative costs for recording, filing and recall items. There were no study-related costs in the usual care group.

Healthcare costs for all children included restorations, extractions and crowns. A single clinician (MP) blinded to both groups reviewed the dental records to identify the treatment requirements and associated item codes based on the current recommended schedule of fees for dental services as prescribed by the Australian Dental Association.27 These costs are used by both the public and private dental services in Australia. Where more than one item code could apply, for example, a one-surface occlusal restoration on the posterior tooth could be either adhesive or metallic, a range of costs was recorded.

Restoration costs were provided separately for each number of surface restorations (eg, 1–5 surfaces decayed) by the incisor and molar teeth categories. A weighted mean cost of all restorations was used in the model by the surface number and type (incisor/molar); £104 (range £92–£167; table 1). As a stainless steel crown was indicated for severe caries and the cost was substantially higher than that of a normal restoration, the cost of crown restorations was included in the model. The cost of extractions was included for cases of non-restorable teeth. The cost of general anaesthesia was included for extractions as general anaesthesia was applied to all children; mean £1707 (high and low values: £810–£2430).11 12 As standard treatment for children awaiting dental treatment, the cost of antibiotics and analgesics was included for a proportion of patients (48%) who had acute infections while on the waiting list for general anaesthesia. Medication costs were valued from national price schedules.28

Table 1.

Model estimates, healthcare costs and sources

| Description | Base case estimate | Sensitivity values |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | Source(s)/justification | ||

| Starting age | 6 months | Teeth erupting age | ||

| Model duration | 5.5 years | Age of deciduous dentition | ||

| Cycle length | 6 months | |||

| Discount rate (costs/effects, %) | 5 | 0 | 7 | |

| Unit costs (£2012) | ||||

| Telephone interview (2 years) | 53 | 49 | 58 | Prevention programme data |

| General anaesthesia | 1707 | 810 | 2430 | Seow et al12 |

| Restoration | 104 | 92 | 167 | ADA schedule of fees27 |

| Crowns | 275 | 264 | 288 | ADA schedule of fees27 |

| Extraction | 169 | 162 | 178 | ADA schedule of fees27 |

| Medication (mean cost of amoxicillin and paracetamol) | 9 | 8 | 12 | PBS code 3302T/3348F28 |

| Probabilities (6 monthly) | ||||

| Incidence of caries in TI | 0.0108 | 0.003 | 0.017 | Prevention programme data n=185 |

| Incidence of caries in UC | 0.0547 | 0.04 | 0.07 | Prevention programme data n=40 |

| New patient is treated within 6 months | 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.82 | Logan clinic data |

| Treatment by restoration (not extracted) | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.61 | Logan clinic data |

| For restorations, proportion of filling only (no crowns) | 0.74 | 0.70 | 0.78 | Logan clinic data |

ADA, Australian Dental Association; PBS, pharmaceutical benefit scheme item codes for amoxicillin and paracetamol paediatric preparation; TI, telephone intervention; UC, Usual care.

Transition probabilities

Movements between the ‘healthy’ and ‘caries’ states every 6 months (figure 1) are the model's transition probabilities and are based on the proportion of children developing caries and being treated (by type of treatment). These were determined from the Logan-Beaudesert clinical database from the last 100 patients under 6 years of age treated under general anaesthesia at the district oral health service from 1 January 2009 and available in children from baseline (6 months of age) to 6 years of age.11 Caries incidence probabilities were available up to 2 years of age for the children in the dental caries prevention programme from the intervention study.23 In the model, rates were converted into probabilities using a rate to probability formula: 1−e–rate × time. We assumed that the 6 monthly caries probabilities (1.1% in the intervention group and 5.5% in the usual care group; table 1) would remain constant until age 6 years. Probabilities for the treatments received were calculated from the Logan-Beaudesert clinical database. Fifty-seven per cent of the caries cases were restored with the remainder needing extraction. Of all the restored teeth, 36% required stainless steel crown treatments (table 1). Only major treatments were considered in the model (eg, restoration only or restoration with crown, or extraction; figure 1).

Analysis

Guidelines for best practice procedures for cost-effectiveness modelling were followed.29 All costs and results are presented in 2012 £ using the purchasing power parity conversion rate of $A1=£0.81.30 The mean costs and numbers of new caries were generated using an expected value analysis, which aggregates the probabilities and values assigned to the different health states. Costs and effects were discounted at 5% per year to adjust to present values. To ensure that the maximum waiting time for treatment in the model reflected that observed in the dental service (18 months), the probability of treatment was altered so that all patients received treatment within 18 months. The probability of a new case of caries being treated within 6 months was 0.79 (95% CI 0.76 to 0.82). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was calculated by dividing the difference in mean costs between the telephone intervention and usual care by the difference in the number of caries. For ease of interpretation, the costs and caries outcomes are presented per 100 children.

To address the uncertainty in the costs and effectiveness estimates, univariate sensitivity analyses were used where each parameter was varied through a range of plausible values and changes to the base results were observed. For all probabilities, 95% CIs were used, and for costs high and low values were determined from the dental item ranges or tested between ±15% (table 1). A probabilistic sensitivity analysis was also performed by resampling 1000 times at random from the probability distributions for each parameter. This procedure is similar to multivariate sensitivity analysis and addresses the uncertainty of all estimates simultaneously. The γ-distributions were used for cost estimates as these fit the often skewed cost distributions, and β-distributions were used for probabilities as these are bounded between 0 and 1.

Results

In the base case, for every 100 children up to 6 years of age, the estimated healthcare costs for children receiving the telephone intervention were £19 926 compared with £89 910 for the usual care group (table 2). The estimated incidence of caries was 11 for the telephone intervention group and 54 for the usual care group per 100 children. Therefore, a total of 43 carious teeth were prevented from the telephone intervention per 100 children at a cost saving of £69 984.

Table 2.

Results of cost-effectiveness for every 100 children (£2012)

| Group | Total costs (£) | Total caries (teeth) | Difference in costs (£) | Caries prevented | ICER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care | 89910 | 54 | |||

| Telephone intervention | 19926 | 11 | –69984 | 43 | Dominant* |

*Usual care is dominated by telephone intervention, as the intervention has better health outcomes and lower costs.

ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

In univariate sensitivity analysis (table 3), the results were most sensitive to the caries incidence in the telephone and usual care groups, the cost of general anaesthesia and the discount rate. The results substantially depended on the incidence of caries in both the telephone prevention and usual care groups. For example, cost savings were estimated to be 20% higher than the base case when the incidence of caries of the telephone intervention was 0.003 (table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate sensitivity analyses per 100 children in each group

| Sensitivity analyses | Cost savings (£2012) | Caries prevented |

|---|---|---|

| Base case | 69984 | 43 |

| Unit costs (£) per child | ||

| Telephone interview (for 6 months; base £13) | ||

| Low £10 | 70302 | 43 |

| High £17 | 69654 | 43 |

| Restorations (base £104) | ||

| Low £92 | 69699 | 43 |

| High £167 | 71323 | 43 |

| Mean medication cost for antibiotics and analgesics (base £9) | ||

| Low £8 | 69960 | 43 |

| High £12 | 70053 | 43 |

| Extraction (base £169) | ||

| Low £162 | 69860 | 43 |

| High £178 | 70123 | 43 |

| General anaesthesia (base £1707) | ||

| Low £810 | 36043 | 43 |

| High £2430 | 97298 | 43 |

| Cost of crowns (base £275) | 69915 | |

| Low £264 | 70046 | 43 |

| High £288 | 43 | |

| Probabilities | ||

| Caries development in telephone intervention (base 0.0108) | ||

| Low 0.003* | 83368 | 51 |

| High 0.017* | 59496 | 37 |

| Caries development in usual care (base 0.0547) | ||

| Low 0.04* | 46833 | 29 |

| High 0.07* | 93328 | 57 |

| A new patient is treated within 6 months (base 0.79) | ||

| Low 0.76 | 69456 | 43 |

| High 0.82 | 70468 | 43 |

| In treatment, proportion of teeth restored (not extracted; base 0.57) | ||

| Low 0.53 | 69968 | 43 |

| High 0.61 | 69697 | 43 |

| In restoration, proportion of filling only (no crowns; base 0.74) | ||

| Low 0.70 | 70216 | 43 |

| High 0.78 | 69741 | 43 |

| Discounting (base costs and effects 5%) | ||

| No discounting | 81405 | 49 |

| 7% discounting | 65934 | 41 |

*Low and high values are 95% CI of the telephone and usual care incidence probabilities calculated using the formula: p±1.96√(p(1−p)/n).

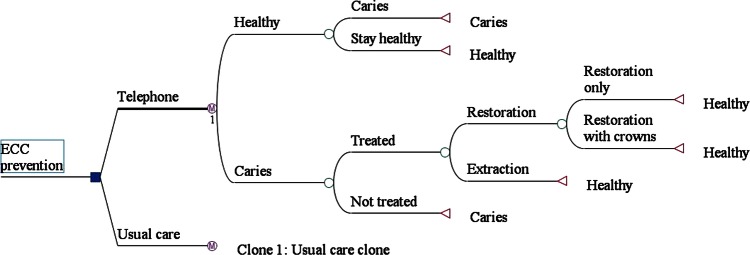

However, only minor changes to the base case results were found when the cost of restorations was altered. When 7% discounting of both costs and effects was used, there was a substantial improvement in cost savings (£81 405) over no discounting (£65 934) accompanied by a 16% increase in prevented caries (table 3). In multivariate sensitivity analysis, the intervention was cost-effective in 100% of simulations because in each simulation the telephone intervention saved costs and reduced caries (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Results from the multivariate sensitivity analysis for incremental cost savings and incremental caries for the telephone interview group compared with the usual care group. The conversion rate of $A to £ was $A1=£0.81 using the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) purchasing power parity rate. The above figure has costs in $A. Each dot represents an incremental cost and incremental caries prevented pairing for 1000 simulations. All dots fall below the $A0 y-axis level and positive x-axis values, so in 100% of simulations the intervention was cost-effective.

Discussion

This is the first cost-effectiveness analysis for ECC prevention in Australia and one of the few worldwide. We found that a telephone intervention programme was highly cost saving for public oral health services. The cost savings were due to the lower caries incidence in the telephone prevention programme and the avoided high costs of treatment. The costs of treatment for young children (less than 4 years of age) in Australia are high because they need to be hospitalised and have general anaesthesia even for small fillings as children of this age are generally uncooperative when receiving treatment in a standard dental chair. The probabilities of caries incidence in the intervention and usual care groups were the most influential variables for determining the overall costs savings.

The relatively small additional cost of delivering the telephone programme was greatly outweighed by the dental treatment costs incurred by the usual care group up to age 6 years. If dental and oral health therapists are financially supported to provide telephone prevention for ECC in disadvantaged social areas, 43 dental caries can be prevented for every 100 children, saving an estimated £69 984 for the public oral health service by the time children are 6 years of age. The model measured the number of carious lesions instead of children as one child can develop more than one carious lesion during the life cycle of the model or until 6 years of age. Furthermore, each additional carious lesion would incur treatment costs. Our analyses showed that these results were robust to the uncertainty in the estimated costs and the efficacy of the telephone intervention. Thus, in both the best and worst case scenarios, investing in a telephone intervention delivered by dental and oral health therapists will significantly reduce caries incidence and treatment costs for the pubic oral health service.

Our findings are in concordance with those of an earlier economic study that evaluated preventive programmes for ECC in a group of Californian children from low-income households.19 These authors also concluded that having a preventive programme is cost-effective by finding that an intervention with examination, varnish and counselling can achieve 70% more averted caries at a cost of US$66 (£53) per caries surface prevented. However, it is unclear whether general anaesthesia costs were included in the costing. Markov modelling techniques have previously been used in evaluating the cost-effectiveness of dental care programmes. Similar to our findings, Warren et al31 also demonstrated in an adult Australian population that a prevention programme was cost-effective in managing caries using a patient simulation Markov model analysis. This study compared the long-term cost and outcomes of a non-invasive monitoring practice programme32 versus standard dental care using clinical trial data in Australian private dental practice. Warren et al31 reported that incremental cost per decayed, missing, filled teeth avoided at 2 years and 3 years, and during the lifetime was US$1287, US$1148 and US$1795, respectively.

Owing to the difficulty of measuring quality-of-life data in a paediatric population, we did not consider the standard outcome measure preferred in cost-effectiveness evaluations of quality-adjusted life years. Quality-of-life gains are possible owing to fewer dental caries through the reduction of pain, family time and expense to attend treatment and other social/educational benefits. Our analyses also did not include the out-of-pocket costs and potential income losses of the children's parents or caregivers to receive treatment. Including these costs would have made the telephone intervention even more cost-effective.

Our model somewhat simplifies the complex process of childhood caries and does not account for the varying eruption time of deciduous teeth and their variable risk for caries in the first 2 years of life. Model estimation was performed with primary data from the intervention study and actual clinical data from the same district. Using data from these two different patient groups may be a limitation of this analysis; however, we do not expect the patient characteristics to differ markedly since they originate from the same district. Also, using actual clinical data outside of the trial may strengthen the study's external validity. The data from 100 randomly selected children who presented for treatment at the same clinic yielded 991 teeth to be treated and increased our sample size in calculating treatment probabilities.

Our results show that a preventive intervention can substantially reduce the overall cost for government by reducing treatment demand. Further research is warranted to examine the cost-effectiveness of alternative prevention programmes effective in reducing ECC incidence. Our current research does not incorporate additional societal costs into the benefit of the programme. However, this may be a particularly difficult target group to reach and extra intervention resources may be required if, for example, mothers do not own a telephone or access is problematic for health staff. It would be useful to incorporate quality of life changes as a result of the reduced caries incidence in the costing model. Measuring utility weights which quantify quality of life in caries health states could provide greater accuracy in determining the actual cost of the disease and potential savings for society.

Conclusions

A telephone prevention programme provided significant cost savings to the health system by reducing caries incidence in the intervention group. Despite the results being sensitive to caries incidence and the cost of general anaesthetics, the relatively inexpensive telephone intervention was predicted to always generate cost savings for the public oral health service in this low socioeconomic district.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: The conception and design of the study was formulated by MP, KP, AGB, LW and WKS. Data collection was undertaken by MP and KP. Economic modelling and data analysis were undertaken by SK, LG and MP. All authors participated in the interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding: We acknowledge the generous funding of this project from the Australian Centre for Health Services Innovation (AusHSI) (grant no. SG0005-000089), the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (grant no. 1046779), and the Office of Health and Medical Research Fellowship Fund, Queensland Health.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: University of Queensland and Queensland Health.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Psoter WJ, Pendrys DG, Morse DE, et al. Associations of ethnicity/race and socioeconomic status with early childhood caries patterns. J Public Health Dent 2006;66:23–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milnes AR. Description and epidemiology of nursing caries. J Public Health Dent [Review] 1996;56:38–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.AAPD Policy on early childhood caries (ECC): classifications, consequences, and preventive strategies. Pediatr Dent 2012;34:50–2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foster T, Perinpanayagam H, Pfaffenbach A, et al. Recurrence of early childhood caries after comprehensive treatment with general anesthesia and follow-up. J Dent Child 2006;73:25–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JY, Bouwens TJ, Savage MF, et al. Examining the cost-effectiveness of early dental visits. Pediatr Dent 2006;28:102–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuhrer CT, 3rd, Weddell JA, Sanders BJ, et al. Effect on behavior of dental treatment rendered under conscious sedation and general anesthesia in pediatric patients. Pediatr Dent 2009;31:492–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berkowitz RJ, Moss M, Billings RJ, et al. Clinical outcomes for nursing caries treated using general anesthesia. ASDC J Dent Child 1997;64:210–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Almeida AG, Roseman MM, Sheff M, et al. Future caries susceptibility in children with early childhood caries following treatment under general anesthesia. Pediatr Dent 2000;22:302–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powell LV. Caries prediction: a review of the literature. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol [Review] 1998;26:361–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook HW, Duncan WK, De Ball S, et al. The cost of nursing caries in a Native American head start population. J Clin Pediatr Dent 1994;18:139–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MSHSD OHPL-B. 2011. General Anaesthic Data Oral Health Logan Hospital.

- 12.Seow WK, Clifford H, Battistutta D, et al. Case-control study of early childhood caries in Australia. Caries Res 2009;43:25–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edelstein B, Vargas CM, Candelaria D, et al. Experience and policy implications of children presenting with dental emergencies to US pediatric dentistry training programs. Pediatr Dent 2006;28:431–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casamassimo PS, Thikkurissy S, Edelstein BL, et al. Beyond the dmft: the human and economic cost of early childhood caries. J Am Dent Assoc 2009;140:650–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slade GD, Reisine ST. The child oral health impact profile: current status and future directions. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2007;35(Suppl 1):50–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies GM, Worthington HV, Ellwood RP, et al. An assessment of the cost effectiveness of a postal toothpaste programme to prevent caries among five-year-old children in the North West of England. Community Dent Health 2003;20:207–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kowash MB, Toumba KJ, Curzon MEJ. Cost-effectiveness of a long-term dental health education program for the prevention of early childhood caries. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2006;7:130–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savage MF, Lee JY, Kotch JB, et al. Early preventive dental visits: effects on subsequent utilization and costs. Pediatrics 2004;114:e418–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramos-Gomez FJ, Shepard DS. Cost-effectiveness model for prevention of early childhood caries. J Calif Dent Assoc 1999;27:539–44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plutzer K, Spencer AJ. Efficacy of an oral health promotion intervention in the prevention of early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2008;36:335–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kowash MB, Pinfield A, Smith J, et al. Effectiveness on oral health of a long-term health education programme for mothers with young children. Br Dent J 2000;188:201–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinstein P, Harrison R, Benton T. Motivating mothers to prevent caries: confirming the beneficial effect of counseling. J Am Dent Assoc 2006;137:789–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plonka K, Pukallus M, Barnett A, et al. A controlled longitudinal study of home visits compared to telephone contacts to prevent early childhood caries. Int J Paediatr Dent 2013;23:23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.PHIDU Population health profile of the Logan area division of general practice: supplement. Adelaide: Public Health Information Development Unit (PHIDU), 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drury TF, Horowitz AM, Ismail AI, et al. Diagnosing and reporting early childhood caries for research purposes. A report of a workshop sponsored by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the Health Care Financing Administration. J Public Health Dent 1999;59:192–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sonnenberg FA, Beck JR. Markov models in medical decision making: a practical guide. Med Decis Making 1993;13:322–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Australian Dental Association. 2009. The Australian Schedule of Dental Services and Glossary Ninth Edition.

- 28.Australian_Government. 2012. Pharmacuetical Benefit Scheme. http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/home (accessed 10 Jul 2012)

- 29.Caro JJ, Briggs AH, Siebert U, et al. Modeling good research practices—overview: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM modeling good research practices task force-1. Med Decis Making 2012;32: 667–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.OECD Purchasing power parities for GDP. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2012. http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?datasetcode=SNA_TABLE4 (accessed 11 Jun 2012).

- 31.Warren E, Pollicino C, Curtis B, et al. Modeling the long-term cost-effectiveness of the caries management system in an Australian population. Value Health 2010;13:750–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Curtis B, Warren E, Pollicino C, et al. The Monitor Practice Programme: is non-invasive management of dental caries in private practice cost-effective? Aust Dent J 2011;56:48–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.