Abstract

Background:

Emergence of high-level aminoglycoside and glycopeptide resistance has significantly contributed to the mortality, particularly in serious enterococcal infections.

Objectives:

This study was aimed to determine the prevalence of high-level gentamicin resistance (HLGR), high-level streptomycin resistance (HLSR) and vancomycin resistance in enterococcal isolates recovered from patients with bacteremia.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 110 blood culture isolates of enterococci were recovered from septicemic patients. Routine antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed and screening for ampilcillin, high-level aminoglycoside resistance (HLAR) and high-level vancomycin resistance was done by agar screen method.

Results:

Out of 110 isolates, Enterococcus faecium accounted for 53% of these isolates, followed by Enterococcus fecalis (33%), Enterococcus casseliflavus (8%), Enterococcus raffinosus (4%) and Enterococcus dispar (2%). Resistance to ampicillin, HLGR, HLSR and HLAR was detected in 58%, 62%, 58% and 54% of the isolates, respectively. No isolate was resistant to vancomycin.

Conclusion:

This study illustrates the high prevalence of HLAR in enterococci from patients with septicemia in our region, which emphasizes the need to predict synergy between beta-lactams and aminoglycosides for management of enterococcal infections.

Keywords: Antibiotic resistance, enterococcus, vancomycin

INTRODUCTION

Intensive use of broad-spectrum antibiotics is responsible for the conversion of enterococci, the otherwise gut commensal bacteria, to opportunistic nosocomial pathogens and important causes of community-acquired infection.[1] It now exhibits intrinsic resistance to penicillinase-susceptible penicillin (low level), penicillinase-resistant penicillin, cephalosporin, nalidixic acid, aminoglycoside and clindamycin,[2] which until recently, could be treated with ampicillin, or vancomycin with or without an aminoglycoside. It also exhibits a low to moderate level resistance to aminoglycosides, corresponding to minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 62-500 μg/ml. This resistance is related to the slow uptake or permeability of these agents.[3]

However, aminoglycoside uptake is enhanced by exposing enterococci to a beta-lactam. High-level aminoglycoside resistance (HLAR) (MIC > 2000 μg/ml) has emerged recently, which is either ribosomally mediated or due to the production of inactivated enzymes. The limited choice of efficient therapy in serious enterococcal infections has been complicated by emergence of resistance to ampicillin, high-level aminoglycoside and glycopeptides. Since this poses a therapeutic challenge to physicians due to the ease at which antimicrobial drug resistance is acquired and transferred in these organisms, we were prompted to study antibiotic-resistant enterococci in blood stream infections, considering the serious impact of the prevalence of such strains in our hospital and community.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 110 blood culture isolates of enterococci recovered from the patients with septicemia from a tertiary care hospital attached to a medical college, between January and December 2009, were included in this prospective study. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee.

The isolates were identified based on colony characters, morphology on gram staining, biochemical reactions, using conventional test scheme by Facklam et al.[4] Identification of Enterococci isolates was confirmed on the basis of the growth of these organisms on bile-esculin medium, presence of gram-positive cocci in pairs and short chains on gram staining of these colonies, catalase-negative colonies and growth of these organisms in 6.5% NaCl and at pH 9.6. Enterococcal strains were further identified to the species level by using conventional physiological tests[5] which are based on carbohydrate fermentation using 1% solution of the following sugars: glucose, mannitol, rabinose, raffinose, sorbitol, sucrose, lactose, trehalose and inulin; by pyruvate utilization in 1% pyruvate broth; arginine decarboxylation in Moellers decarboxylase broth; hippurate hydrolysis; motility test; pigment production detected on tryptic soya agar (TSA); gelatin liquefaction; starch hydrolysis using 2% starch and polysaccharide production. A single colony isolate was inoculated into 5 ml Todd-Hewitt broth and incubated overnight at 37°C which was then added as an inoculum of one drop with the help of Pasteur pipette. All tests were incubated at 37°C and read at 24 hours and 7 days. The antibiotic susceptibility testing was done by Kirby Bauer disc diffusion method using Mueller Hinton agar plates (Hi Media Laboratories, Mumbai, India). Enterococcus faecalis, ATCC 29212 and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 were included as reference strains, for quality control in susceptibility testing. Beta-lactamase production was determined by nitrocefin disc method (Hi Media Laboratories).[6]

Screening for high-level aminoglycoside and vancomycin resistance was performed by the agar screen method according to Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) recommendations.[6] Briefly, brain heart infusion agar (BHIA; Hi Media Laboratories), containing gentamicin (500 μg/ml), streptomycin (2000 μg/ml), and vancomycin (6 μg/ml) was used. Unsupplemented BHIA served as the control. The medium was inoculated via spotting of 10 μl of inoculum containing 106 colony forming units (CFU) of the test strain; plates were incubated for 24 hours at 35°C for gentamicin, vancomycin, and for 48 hours for streptomycin. The presence of growth indicated resistance. The MIC of vancomycin was determined by using agar dilution method.[7] Chi-square test was used to analyze the results. P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

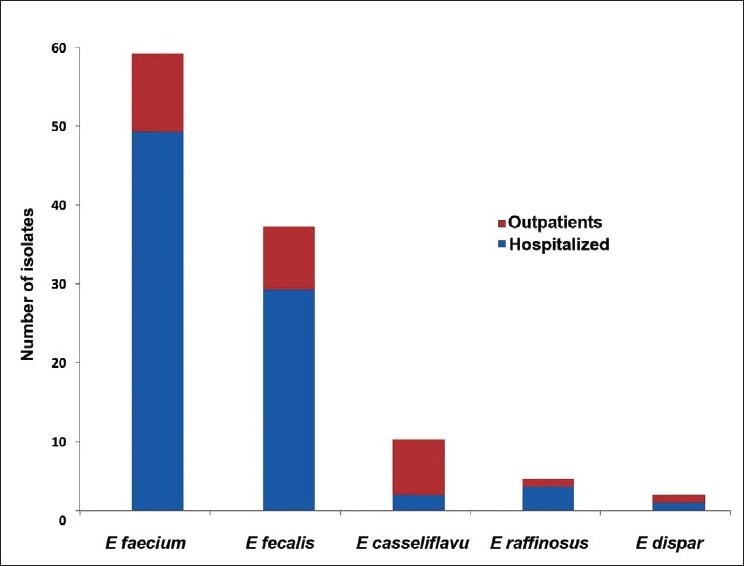

In the present study, enterococcal bacteremia was caused by Enterococcus faecium [58/110 (53%)], followed by Enterococcus fecalis [36/110 (33%)], Enterococcus casseliflavus [9/110 (8%)], Enterococcus raffinosus [4/110 (4%)] and Enterococcus dispar [3/110 (2%)]. 75% (83/110) strains were recovered from hospitalized patients [ICU (52%), pediatric ICU (36%), surgical (12%), oncology (8%) and medical wards (2%)] and 24% (27/110) strains were isolated from outpatients [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Distribution of various enterococcal species among hospitalized and outpatients

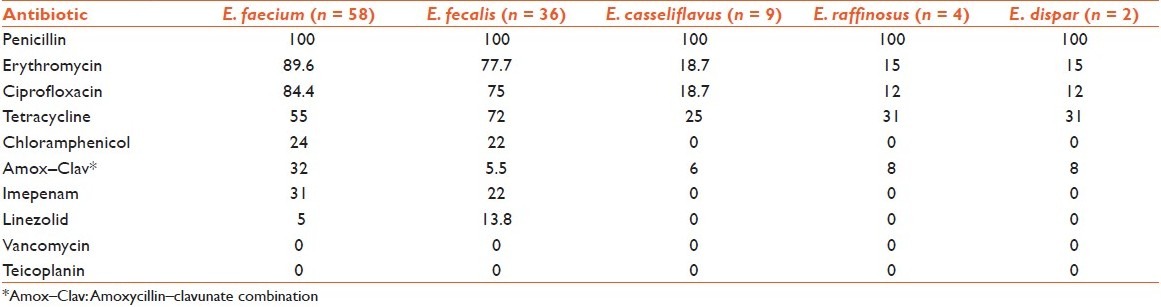

Antimicrobial resistance profile of enterococcal isolates shows that resistance was most frequently observed with penicillin (100%), erythromycin (76%) and ciprofloxacin (72%). Multidrug resistance was found in 54% (59/110) enterococcal isolates, and out of these, 67% (39/58) were E. faecium strains. No beta-lactamase production was observed in any isolate [Table 1].

Table 1.

Percentage distribution of antibiotic resistance pattern

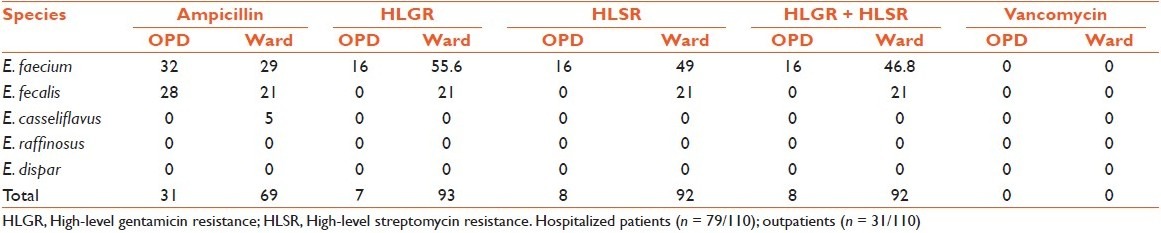

Ampicillin, high-level gentamicin resistance (HLGR) and high-level streptomycin resistance (HLSR) was detected in 58% (64/110), 60% (66/110) and 55% (61/110) of the isolates, respectively [Table 2]. Disc diffusion and agar screen results were concordant for HLAR. Multiple antibiotic resistance patterns were observed in 71% (42/59) HLAR isolates. Three isolates (one E. faecium, two E. fecalis) were found to be moderately sensitive to vancomycin by disc diffusion with MIC of 8 mg/ml, while all the rest of the isolates were sensitive. Interestingly, these moderately sensitive E. fecalis isolates were HLGR and also multidrug resistant.

Table 2.

Resistance distribution (%) among enterococcal isolates from hospitalized patients and outpatients

DISCUSSION

Enterococci are widely distributed in nature. The prevalence of enterococcal bacteremia among hospitalized and outpatients in the present study was 72% and 28%, respectively. Historically, the ratio of infections due to E. faecalis to those due to all other Enterococcus species is approximately 10:1 in which there has been a progressive decline in recent years.[7] E. faecium leading to bacteremia was higher in prevalence than E. fecalis (53% and 33%, respectively) in this study, and prevalence of relatively high proportion of E. faecium from the study setting was consistent with those reported in other Indian studies from various clinical samples (40–71%).[8–10]

Multidrug-resistant enterococci are being increasingly reported from all over the world. The frequency of penicillin and ampicillin resistance was high in the present study (100% and 58%, respectively). Reports of the steady rise in the recovery rates of ampicillin-resistant enterococci (ARE) have been available in the recent past in India.[10] Many studies have also demonstrated that E. faecium is comparatively more resistant than E. faecalis.[10,11,12,13] In the present study, resistance rates for ampicillin, penicillin and chloramphenicol were comparable in E. faecium and E. faecalis; while E. faecium showed higher rates of resistance to erythromycin, amoxycillin–clavunate, ciprofloxacin, tetracycline and imepenam. Frequent use of ampicillin, macrolides and quinolones for the empirical treatment of endemic infectious diseases and for treatment of enterococcal infections may be the cause of the high proportion of antibiotic resistant pattern seen in the isolates.

The present study demonstrated high prevalence of HLGR, HLSR, and HLAR (resistance to both gentamicin and streptomycin) among enterococci (60%, 55% and 54%, respectively). Though the detection of HLAR in hospitalized patients (92%) was high, nevertheless, occurrence of such strains in community is also evident (8%). A recent study from South India reported a low fecal carriage of 2% and 4% of HLGR and HLSR enterococci, respectively.[10] HLAR was more frequently observed in E. faecium isolates (71%) than other species. Previous studies on HLAR have been done almost exclusively on E. faecalis. In a study during 1989–1996, quite a low prevalence of E. fecalis isolated from blood was found to be HLGR, HLSR and HLAR (16%, 10% and 3.6%, respectively).[14] However, more recently, high prevalence of HLAR seems to be associated with a high relative proportion of E. faecium compared with E. faecalis. In studies from North India in 2001, a higher prevalence of HLAR enterococcal isolates was reported.[15,16] In another study from North India in 2004, HLGR was reported in 62% of E. fecalis and 77% of E. faecium.[11] In the subsequent year, even higher percentages of E. fecalis and E. faecium isolates from Delhi exhibited HLAR (72% and 81%, respectively).[8] Such a finding has unfavorable consequences for a patient with serious enterococcal infections since the synergistic anti-enterococcal effect of cell-wall–active agents (ampicillin, penicillin, vancomycin) and aminoglycosides is abrogated by HLAR. In such situations, combinations of penicillin with vancomycin, ciprofloxacin with ampicillin, or novobiocin with doxycycline, among others, have been used but can be unpredictable and remain clinically unproven.[17] The HLAR strains were isolated most frequently from surgical ward followed by intensive care unit which necessitates regular local surveillance and stringent infection control measures for prompt detection of such strains and prevent their colonization and dissemination in other patients.

With the spread of strains showing HLAR, there is now rampant use of vancomycin in hospitals since it is the only available alternative for treatment. Based on our findings, good anti-enterococcal activity was observed in 100% with both teicoplanin and vancomycin, followed by linezolid, imepenam, chloramphenicol (93%, 76% and 80% sensitivity, respectively). Vancomycin resistance rates are very low in India and vancomycin resistant enterococci (VRE) are sporadic and infrequent;[15] nonetheless, there is a need for constant monitoring. 100% sensitivity has been observed for linezolid,[8,10,13,18] which may be reserved as a second-line drug for VRE. However, the clinicians should resist the empirical use of these only available therapeutic options at present.

In conclusion, the present study illustrates the high prevalence of HLAR in enterococci from patients with bacteremia in our region. Resistance to multiple antibiotics and inactivity to the synergistic killing of combination therapy of penicillin and aminoglycosides have given an excellent opportunity to enterococci to survive and become secondary invaders in hospital infection. Hence, this study emphasizes the need to screen for HLAR in enterococcus strains from patients with septicemia for predicting synergy between beta-lactams and aminoglycosides for enterococci. Routine screening for vancomycin resistance among clinical isolates, active surveillance for VRE in intensive care units and surgery wards and restriction of injudicious use of vancomycin needs to be implemented.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schaberg DR, Culver DH, Gaynes RP. Major trends in the microbial etiology of nosocomial infection. Am J Med. 1991;91:72–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90346-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray BE. The life and times of the enterococcus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:45–65. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isenberg HD, editor. Tests to detect high-level aminoglycoside resistance in enterococci. Vol. 1. Washington DC: American Society of Microbiol; 1992. Clinical microbiology procedure handbook; pp. 541–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Facklam RR, Collins MD. Identification of Enterococcus species isolated from human infections by a conventional test scheme. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:731–4. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.4.731-734.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Facklam RR, Carey RD, Ballows A, Hausler WJ, Shadomy HJ. The streptococci and aerococci. In: Lennette EN, editor. Manual of clinical Microbiology. 4th ed. Washington. D. C: American Society for Microbiol; 1985. pp. 154–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forbes BA, Sahm DF, Weissfeld AS, editors. Approaches to diagnosis of infectious diseases and evaluation of antimicrobial activity. 12 ed. Washington DC: Mosby Elsevier; 2007. Diagnostic Microbiology; pp. 78–215. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. 9th ed. Wayne (PA): Approved Standard M2- A9 CLSI document; 2006. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohanty S, Jose S, Singhal R, Sood S, Dhawan B, Das BK, Kapil A. Species prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of enterococci isolated in a tertiary care hospital of North India. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2005;36:962–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De A, Bindlish A, Kumar S, Mathur M. Vancomycin resistant enterococci in a tertiary care hospital in Mumbai. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2009;27:375–6. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.55451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sekar R, Srivani R, Vignesh R, Kownhar H, Shankar EM. Low recovery rates of high-level aminoglycoside-resistant enterococci could be attributable to restricted usage of aminoglycosides in Indian settings. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:397–8. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47604-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghoshal U, Garg A, Tiwari DP, Ayyagari A. Emerging vancomycin resistance in enterococci in India. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2006;49:620–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centinkaya Y, Falk P, Mayhall CG. Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:686–707. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.4.686-707.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Udo EE, AL-Sweih N, Philips OA, Chugh TD. Species prevalence and antibacterial resistance of Enterococci isolated in Kuwait hospitals. J Med Microbiol. 2003;52:163–8. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.04949-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paterson D, Bodman J, Thong ML. High level aminoglycoside resistant Enterococcal blood culture isolates. Comm Dis Intell. 1996;20:532–5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Randhawa VS, Kapoor L, Singh V, Mehta G. Aminoglycoside resistance in enterococci isolated from paediatric septicaemia in a tertiary care hospital in north India. Indian J Med Res. 2004;119:77–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathur P, Kapil A, Chandra R, Sharma P, Das B. Antimicrobial resistance in Enterococcus faecalis at a tertiary care centre of northern India. Indian J Med Res. 2003;118:25–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caron F, Pestel M, Kitzis MD, Lameland JF, Humbert G, Gutmaan L. Comparison of different beta lactams-glycopeptides-gentamicin combinations for an experimental endocarditis caused by a highly glycopeptides resistant isolate of enterococcus faecium. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:106–12. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhat KG, Paul C, Bhat MG. High level aminoglycoside resistance in enterococci isolated from hospitalized patients. Indian J Med Res. 1997;105:198–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]