Abstract

Context:

Prevalence of hypothyroidism is 2–4% in women in the reproductive age group. Hypothyroidism can affect fertility due to anovulatory cycles, luteal phase defects, hyperprolactinemia, and sex hormone imbalance.

Aims and Objectives:

To study the prevalence of clinical/sub-clinical hypothyroidism in infertile women and the response of treatment for hypothyroidism on infertility.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 394 infertile women visiting the infertility clinic for the first time were investigated for thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and prolactin (PRL). Infertile women with hypothyroidism alone or with associated hyperprolactinemia were given treatment for hypothyroidism with thyroxine 25–150 μg.

Results:

Of 394 infertile women, 23.9% were hypothyroid (TSH > 4.2 μIU/ml). After treatment for hypothyroidism, 76.6% of infertile women conceived within 6 weeks to 1 year. Infertile women with both hypothyroidism and hyperprolactinemia also responded to treatment and their PRL levels returned to normal.

Conclusion:

Measurement of TSH and PRL should be done at early stage of infertility check up rather than straight away going for more costly tests or invasive procedures. Simple, oral hypothyroidism treatment for 3 months to 1 year can be of great benefit to conceive in otherwise asymptomatic infertile women.

Keywords: Hypothyroidism, infertility, subclinical, treatment

INTRODUCTION

Undiagnosed and untreated thyroid disease can be a cause for infertility as well as sub-fertility. Both these conditions have important medical, economical, and psychology implications in our society. Thyroid dysfunction can affect fertility in various ways resulting in anovulatory cycles, luteal phase defect, high prolactin (PRL) levels, and sex hormone imbalances. Therefore, normal thyroid function is necessary for fertility, pregnancy, and to sustain a healthy pregnancy, even in the earliest days after conception. Thyroid evaluation should be done in any woman who wants to get pregnant with family history of thyroid problem or irregular menstrual cycle or had more than two miscarriages or is unable to conceive after 1 year of unprotected intercourse. The comprehensive thyroid evaluation should include T3, T4, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), and thyroid autoimmune testing such as thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies, thyroglobin/antithyroglobin antibodies, and thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI). Thyroid autoimmune testing may or may not be included in the basic fertility workup because the presence of thyroid antibodies doubles the risk of recurrent miscarriages in women with otherwise normal thyroid function.[1–3]

Prevalence of hypothyroidism in the reproductive age group is 2–4% and has been shown to be the cause of infertility and habitual abortion.[4,5] Hypothyroidism can be easily detected by assessing TSH levels in the blood. A slight increase in TSH levels with normal T3 and T4 indicates subclinical hypothyroidism whereas high TSH levels accompanied by low T3 and T4 levels indicate clinical hypothyroidism.[6] Subclinical hypothyroidism is more common. It can cause anovulation directly or by causing elevation in PRL. It is extremely important to diagnose and treat the subclinical hypothyroidism for pregnancy and to maintain it unless there are other independent risk factors. Many infertile women with hypothyroidism had associated hyperprolactinemia due to increased production of thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH) in ovulatory dysfunction.[7,8] It has been recommended that in the presence of raised PRL, the treatment should be first given to correct the hypothyroidism before evaluating other causes of raised PRL. Measurement of TSH and PRL is routinely done as a part of infertility workup. Due to the lack of population-based infertility data of women with subclinical hypothyroidism in our state, we planned to study the prevalence of hypothyroidism in infertile women as well as to assess their response to drug treatment for hypothyroidism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted on 394 women (age group 20–40 years) on their first visit to Infertility Clinic of Gynecology and Obstetrics Department of a tertiary care hospital attached to a Medical College in North India from February 2007 to March 2010. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee and was conducted after taking informed, written consent of the participants. Infertile women having tubular blockage, pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis on diagnostic laparoscopy or hysteroscopy and with genital TB (PCR-positive); with liver, renal or cardiac diseases; those already on treatment for thyroid disorders or hyperprolactinemia; or cases where abnormality was found in husband's semen analysis also were excluded from the study.

Routine investigations such as random blood sugar (RBS), renal functions tests (RFT), hemogram, urine routine, and ultrasound (as and when required) were done. TSH and PRL were measured by the electrochemiluminesence method as per the instruction manual for Elecsys, 2010 (Roche, USA). Normal TSH and PRL levels were 0.27–4.2 μIU/ml and 1.9–25 ng/ml, respectively, as per kit supplier's instruction. Therefore, hypothyroidism was considered at TSH levels of > 4.2 μIU/ml and hyperprolactinemia at PRL levels of >25 ng/ml.

Thyroxine 25–150 μg (Thyrox, Thyronorm, Eltroxin) was given to hypothyroid infertile females depending upon TSH levels. Statistical analysis of results was carried out using percentages.

RESULTS

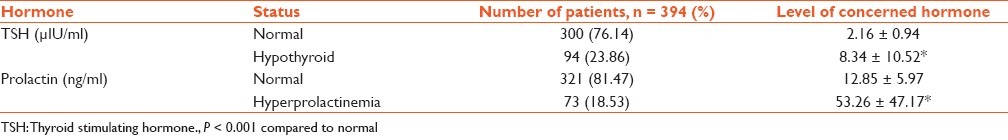

Of the 394 women enrolled for the study, 76 (19.29%) infertile women had raised TSH levels only, 54 (13.7%) infertile females had raised PRL levels only, and 18 (4.57) infertile female have raised levels of both TSH and PRL, which may be due to hypothalamic and/or pituitary diseases. In 94 hypothyroid infertile females, the mean TSH levels were 8.34 ± 10.52 μIU/ml, and in 72 infertile women with hyperprolactinemia the mean PRL levels were 53.26 ± 47.17 ng/ml; and the difference in the levels of both these hormones in infertile women with hypothyroidism and/or hyperprolactinemia was highly significant compared to infertile women with normal levels (P < 0.001) [Table 1]. Depending upon the TSH levels, hypothyroid infertile women were further subdivided into subclinical (TSH 4–6 μIU/ml) and clinical (TSH > 6 μIU/ml) hypothyroidism. It was found that 59 (62.7%) of hypothyroid infertile women were with subclinical and remaining 35 (37.3%) were with clinical hypothyroidism.

Table 1.

Serum thyroid stimulating hormone and prolactin levels in 394 infertile females

Of the 94 infertile women diagnosed with hypothyroidism (alone or with hyperprolactinemia), 72 (76.6%) infertile women conceived after treatment with drugs for hypothyroidism (dose depending upon severity of hypothyroidism, i.e. TSH levels). Of these 72 women, 45 (62.5%) women conceived after 6 weeks to 3 months of therapy and 27 (37.5%) women conceived after 3 months to 1 year of therapy. We further found that hypothyroid infertile women with associated hyperprolactinemia also responded to treatment for hypothyroidism and they conceived.

DISCUSSION

Thyroid hormones have profound effects on reproduction and pregnancy. Thyroid dysfunction is implicated in a broad spectrum of reproductive disorders, ranging from abnormal sexual development to menstrual irregularities and infertility.[9,10] Hypothyroidism is associated with increased production of TRH, which stimulates pituitary to secrete TSH and PRL. Hyperprolactinemia adversely affects fertility potential by impairing GnRH pulsatility and thereby ovarian function.[2,11,12] Gynecologists mostly check TSH and PRL levels in every infertile female, regardless of their menstrual rhythm.

In USA, TSH and PRL levels were checked at the time of the couple's initial consultation for infertility.[8] In our study, the prevalence of hypothyroidism was 23.9% (sub-clinical 62.7% and clinical 37.3%) and hyperprolactinemia was 18.3%, which is higher than in USA. The prevalence of hyperprolactinemia was higher in Iraq (60%) and even in Hyderabad, India, it is higher (41%) as compared to the present study in North India. Hyperprolactinemia may result from stress, and the variable prevalence may be due to the different stress levels in different areas.[2,8]

Thyroid dysfunction is a common cause of infertility which can be easily managed by correcting the appropriate levels of thyroid hormones.[11,13] It has been recommended that in the presence of raised TSH along with raised PRL levels, the treatment should be first to correct the hypothyroidism before evaluating further causes of hyperprolactinemia. Hormone therapy with thyroxine is the choice of treatment in established hypothyroidism. It normalizes the menstrual cycle, PRL levels and improves the fertility rate. Therefore, with simple oral treatment for hypothyroidism, 76.6% infertile women with hypothyroidism conceived after 6 weeks to 1 year of therapy. We tried to maintain normal TSH levels; compliance and adequacy of hypothyroid drug dose were checked by TSH measurement after 6 to 8 weeks interval.

Therefore, the normal TSH levels are the pre-requisite requirements for fertilization. The decision to initiate thyroid replacement therapy in subclinical hypothyroidism at early stage is justified in infertile women. Our data also indicate that variations in TSH levels in the narrower range or borderline cases, i.e. 4–5, 5–6, and >6.0 μIU/ml, should not be ignored in infertile women which are otherwise asymptomatic for clinical hypothyroidism. This group of infertile women, if only carefully diagnosed and treated for hypothyroidism, can benefit a lot rather than going for unnecessary battery of hormone assays and costly invasive procedures. For better management of infertility cause, we should plan further studies with the large sample size and long-term follow-up which are necessary to validate the variation in TSH and PRL levels.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Poppe K, Velkeniers B, Glinoer D. The role of thyroid autoimmunity in fertility and pregnancy. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2008;4:394–405. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poppe K, Velkeniers B. Thyroid disorders in infertile women. Ann Endocrinol. 2003;64:45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akhter N, Hussan SA. Subclinical hypothyroidism and hyper prolactinemia in infertile women: Bangladesh perspective after universal salt iodination. [Last accessed on 2011 Aug 16];Internet J Endocrinol. 2009 5 Available from: http://www.ispub.com/journal/the-internet-journal-of-endocrinology/volume-5-number-1/sub-clinical-hypothyroidism-and-hyperprolactinemiain-infertile-women-bangladesh-perspective-after-universal-saltiodination.html . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lincoln R, Ke RW, Kutteh WH. Screening for hypothyroidism in infertile women. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:455–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krassas GE. Thyroid disease and female reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:1063–70. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)01589-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson S, Pederson KM, Bruun NH, Laurberg P. Narrow individual variations in serum T4 and T3 in normal subjects; a clue to the understanding of subclinical thyroid disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1068–72. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raber W, Gessl A, Nowotny P, Vierhapper H. Hyperprolactnemia in hypothyroidism; clinical significance and impact of TSH normalization. Clin Endocrinol. 2003;58:185–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olivar AC, Chaffkin LM, Kates RJ, Allan TR, Beller P, Graham NJ. Is it necessary to obtain serum levels of thyroid stimulating hormone and prolactin in asymptomatic women with infertility? Conn Med. 2003;67:393–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bercovici JP. Menstrual irregularities and thyroid diseases. Feuillets de biologie. 2000;74:1063–70. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaquero E, Lazzarin CD, Valensise H, Moretti C, Ramanini C. Mild thyroid abnormalities and recurrent spontaneous abortion: Diagnostic and therapeutic approach. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2000;43:204–8. doi: 10.1111/j.8755-8920.2000.430404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis LB, Lathi RB, Dahan MH. The effect of infertility medication on thyroid function in hypothyroid women who conceive. Thyroid. 2007;17:773–7. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poppe K, Velkenier B, Glinoer D. Thyroid disease and female reproduction. Clin Endocrinol. 2007;66:309–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dajan CM, Saravanan P, Bayly G. Whose normal thyroid function is better –yours or mine? Lancet. 2002;360:353–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09602-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]