Abstract

Although heat-shock protein 70 (HSP70), an evolutionarily highly conserved molecular chaperone, is known to be post-translationally modified in various ways such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination and glycosylation, physiological significance of lysine methylation has never been elucidated. Here we identify dimethylation of HSP70 at Lys-561 by SETD1A. Enhanced HSP70 methylation was detected in various types of human cancer by immunohistochemical analysis, although the methylation was barely detectable in corresponding non-neoplastic tissues. Interestingly, methylated HSP70 predominantly localizes to the nucleus of cancer cells, whereas most of the HSP70 protein locates to the cytoplasm. Nuclear HSP70 directly interacts with Aurora kinase B (AURKB) in a methylation-dependent manner and promotes AURKB activity in vitro and in vivo. We also find that methylated HSP70 has a growth-promoting effect in cancer cells. Our findings demonstrate a crucial role of HSP70 methylation in human carcinogenesis.

HSP70 is a molecular chaperone that aids protein folding. In this study, HSP70 is shown to be methylated and this post-translationally modified protein is elevated in expression in human cancers and promotes the activity of Aurora kinase B.

HSP70 is a molecular chaperone that aids protein folding. In this study, HSP70 is shown to be methylated and this post-translationally modified protein is elevated in expression in human cancers and promotes the activity of Aurora kinase B.

S-adenosyl-L-methionine is the most commonly used methyl donor in cellular biochemistry and the second most common enzyme cofactor following ATP1. In recent years, it has become clear that methyl groups are one of major elements regulating protein function2. Although the C-terminal carboxyl group and arginine methylation have been implicated in several cellular responses, including receptor signalling, protein transport and transcription3, lysine methylation has mainly been found and analysed in histones4. Although several non-histone proteins methylated at their lysine residues have also been reported5,6,7,8, physiological roles of lysine methylation on non-histone proteins, especially in human disease such as cancer, still remains largely unknown.

Heat-shock protein 70 (HSP70 or HSPA1A) is a ubiquitous molecular chaperone that functions in a myriad of biological processes, including modulation of polypeptide folding, protein degradation, translocation across membranes and protein–protein interactions9. This protein is post-translationally modified in various ways such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination and glycosylation10,11,12. For instance, the C-terminal phosphorylation of HSP70 serves as a switch for regulating co-chaperone binding and this phosphorylation is directly associated with increased proliferation rate in cancer cells13. In addition, parkin, a human protein that is related to Parkinson's disease, mediates the multiple monoubiquitination of HSP70 to achieve alternate biological outcomes12. Parkin interacts with HSP70 specifically through its second RING finger motif, and disease-associated mutations in or near this RING finger selectively impair the ubiquitination of HSP70, which implies the involvement of HSP70 ubiquitination in parkin-linked parkinsonism12. However, the physiological significance of lysine methylation has not been elucidated.

In this study, we demonstrated that lysine 561 of HSP70 is dimethylated and this methylation is significantly increased in cancer cells. Furthermore, K561 dimethylation regulates the subcellular localization of HSP70 and promotes the proliferation of cancer cells through the interaction with Aurora kinase B (AURKB). This is the first report to describe the physiological significance of lysine methylation on HSP70.

Results

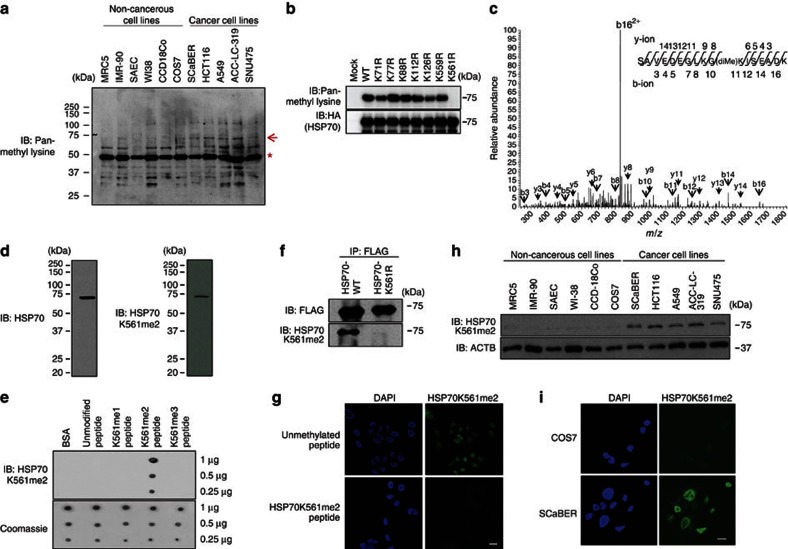

K561 dimethylation of HSP70 is elevated in cancer cells

To identify highly methylated proteins specifically in cancer cells, we conducted western blot (WB) analysis with an anti-pan-methyl lysine antibody14 in six non-cancerous cell lines (MRC5, IMR-90, SAEC, WI38, CCD-18Co and COS7) and five cancer cell lines (SCaBER, HCT116, A549, ACC-LC-319 and SNU475). We observed a highly methylated protein of nearly 70 kDa in cancer cells compared with non-cancerous cell lines (Fig. 1a). To characterize it, we performed mass spectrometric analysis and detected it to be HSP70. To determine in vivo methylation sites, haemagglutinin (HA)-tagged HSP70 was purified from 293T cells and analysed with a Nanoflow-LC combined ion-trap mass spectrometer (LC-MS/MS (liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry)). We picked up 7 candidate lysine residues with mono-, di- and trimethylation in 13 peptides (Supplementary Table S1). We subsequently constructed plasmids with a point mutation at each candidate site and found that K561 is the strongest candidate methylation site on HSP70, because the substitution of this lysine to arginine (K561R) completely abolished methylation by WB analysis (Fig. 1b). In Fig. 1c, we show a typical MS/MS spectrum of dimethylation on K561 that is highly conserved in the HSP70 orthologues from Drosophila auraria to human (Supplementary Fig. S1a). However, this lysine methylation was not present in HSC70 (Supplementary Fig. S1b). On the basis of this result, we generated an antibody against a synthetic peptide containing dimethylated K561 (GLKGK[diMe]ISEADKC) and confirmed that the antibody had high affinity and specificity to dimethylated K561 by immunoblot (Fig. 1d) and dot blot (Fig. 1e) analyses. Western blot analysis using wild-type HSP70 (HSP70-WT) and mutant HSP70 with substitution of lysine 561 to arginine (HSP70-K561R) with the anti-HSP70K561me2 antibody confirmed specific recognition of K561-methylated HSP70 (Fig. 1f). A peptide competition assay revealed that dimethylated K561 synthetic peptide significantly inhibited the fluorescent staining in HeLa cells stained with the antibody, whereas non-methylated peptide hardly affect the signals, indicating that the antibody is highly specific for HSP70 with dimethylated K561 in the cells by immunocytochemistry (Fig.1g). We used the anti-HSP70K561me2 antibody for WB analysis as well as immunocytochemical analysis of HSP70 methylation in six non-cancerous cell lines, and five cancer cell lines confirmed high levels of HSP70 methylation specifically in cancer cells (Fig. 1h,i). To identify a methyltransferase(s) that methylates K561 of HSP70, we conducted WB analysis after transfection of COS7 cells with expression vectors of various types of histone methyltransferases (EHMT1, EHMT2, SMYD2, SMYD3, SUV420H1, SUV420H2, SUV39H1, SUV39H2, SETD7, SETD8, SETD1A and WHSC1L1) into COS7 cells that are most suitable to monitor HSP70 methylation, and observed significant enhancement of K561 dimethylation of HSP70 in which SETD1A was introduced (Supplementary Fig. S2a). Subsequent immunocytochemical analysis using COS7 cells transfected with SETD1A indicated a significant elevation of K561 dimethylation of HSP70, compared with parental COS7 cells (Supplementary Fig. S2b). Consistently, knockdown of SETD1A diminished dimethylation of HSP70K561, and its methylation was rescued by transfection with small interfering RNA (siRNA)-resistant SETD1A expression vector (Supplementary Fig. S2c), indicating that HSP70K561 methylation is likely to be regulated by SETD1A methyltransferase.

Figure 1. Lys 561 dimethylation of HSP70 is enhanced in human cancer.

(a) Methylated proteins detected by anti-pan-methyl lysine antibody. Lysates from six non-cancerous cell lines and five cancer cell lines were immunoblotted with anti-pan-methyl lysine antibody. *, According to our previous work, the strong band at around 50 kDa appears to be EF-1α protein14. (b) Methylation status of HSP70 mutants. 293T cells were transiently transfected with indicated mutants. After purification with anti-HA antibody, HSP70 was immunoblotted with an anti-pan methyl lysine antibody. (c) Nanoflow LC-MS/MS analysis of dimethylated Hsp70 peptide (positions from 551 to 567). Observed b-ions and y-ions are as follows: b3 (258.22), b4 (387.07), b5 (502.76), b7 (688.04), b8 (801.30), b10 (986.41), b11 (1142.34), b12 (1255.45), b14 (1471.53), b16 (1657.22), b162+ (829.67), y3 (333.06), y4 (461.99), y5 (549.48), y6 (662.34), y8 (875.54), y9 (1003.42), y11 (1173.44), y12 (1302.40), y13 (1417.31), y14 (1546.75). (d,e) Validation of the anti-K561-dimethylated HSP70 (HSP70K561me2) antibody. Western blot of HeLa-cell lysates (d) and dot blot analysis using unmodified peptide (GLKGKISEADKC), K561me1 peptide (GLKGK[me1]ISEADKC), K561me2 peptide (GLKGK[me2]ISEADKC) and K561me3 peptide (GLKGK[me3]ISEADKC) (e) were conducted. An anti-HSP70 antibody (SPA-810; Stressgen) was used as an internal control of western blot. (f) Wild-type HSP70 (HSP70-WT) and mutant HSP70 containing a substitution of Lys 561 to arginine (HSP70-K561R) expression vectors were transfected into 293T cells. Cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG M2 agarose (Sigma-Aldrich) 48 h after the transfection, and immunoblotted with anti-FLAG and anti-HSP70 K561me2 antibodies, respectively. (g) The HSP70 K561me2 antibody (1 mol) was pre-incubated for 12 h with methylated HSP70 peptide or unmethylated HSP70 peptide (20 mol) and used in immunocytochemical assays. Cells were co-stained with anti-HSP70 K561me2 (Alexa Fluor 488 (green)) and 4′,6-Diamidino-2′-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI (blue)). Scale bar, 20 μm. (h) HSP70 K561 dimethylation in various cell lines. Lysates from six non-cancerous cell lines and five cancer cell lines were immunoblotted with anti-HSP70 K561me2 and anti-ACTB (internal control) antibodies. (i) Immunocytochemical assays for anti-HSP70 K561me2 (green) and DAPI (blue) in COS7 and SCaBER cell lines. Cells were stained with anti-HSP70 K561me2 (green) and DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 20 μm.

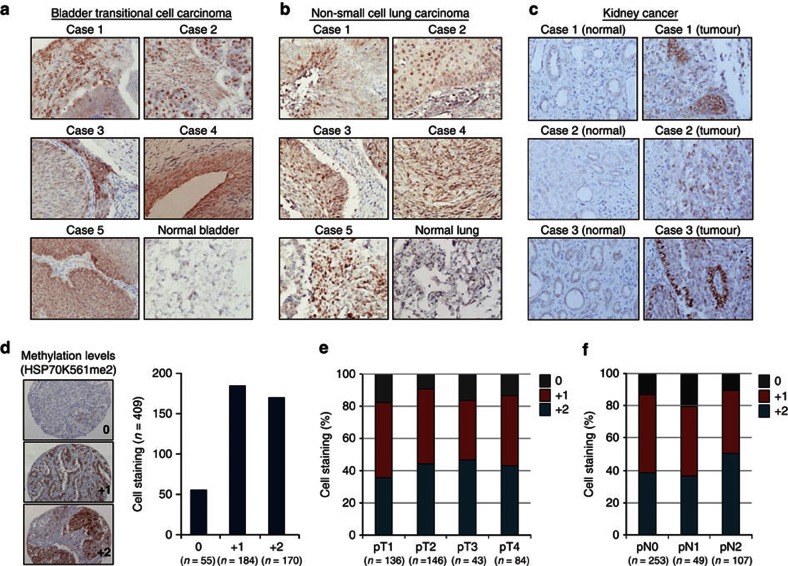

K561 dimethylation status in clinical tissues

As K561 dimethylation of HSP70 is significantly elevated in cancer cells, we conducted expression profile analysis of SETD1A using a number of clinical tissues. First, we analysed 74 bladder cancer samples and 12 normal control samples (British) by quantitative real-time PCR, and found significant elevation of SETD1A expression in tumour cells compared with corresponding non-neoplastic tissues (P=0.0054, Mann–Whitney U-test; Supplementary Fig. S3a). To examine protein expression levels of SETD1A in cancer cells, we conducted WB analysis using cell lysates of two non-cancerous cell lines (CCD-18Co and HFL1) and nine cancer cell lines (SBC5, RERF-LC-AI, A549, HCT116, Alexander, UMUC3, SCaBER, LoVo and MDA-MB-231), and confirmed the elevation of SETD1A protein in cancer cells (Supplementary Fig. S3b). Subsequently, we conducted immunohistochemical analysis using tissue microarrays to analyse SETD1A protein expression in more detail. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S3c, SETD1A protein is overexpressed in lung cancer tissues, and among 36 lung cancer cases, 19 cases (52.8%) showed stronger staining intensity than normal tissues (Supplementary Table S2). In addition, tissue microarray analysis of liver tissues revealed that SETD1A protein is also overexpressed in liver cancer tissues (Supplementary Fig. S3d), and of 67 liver tumour tissue sections examined, the intensity of SETD1A in 30 tumour cases (44.8%) was higher than that in normal tissues (Supplementary Table S3). These results imply that SETD1A protein is overexpressed in various cancer types. Furthermore, to investigate whether SETD1A is indispensable for cancer cell viability, we performed cell growth assays and found significant growth suppression of bladder and lung cancer cell lines (RT4, A549, ACC-LC-319 and SBC5) treated with SETD1A siRNAs, compared with control siRNAs (siEGFP and siNC; Supplementary Fig. S4). Taken together, SETD1A is overexpressed in various cancer types and seems to have a role in the growth regulation of cancer cells.

We then investigated the K561 dimethylation status of HSP70 in clinical tissues by immunohistochemical analysis, using bladder, lung and kidney cancer tissue microarrays, and found its strong staining in the nuclei of malignant cells, whereas no staining was observed in non-neoplastic tissues (Fig. 2a–c). Among 409 lung cancers (non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC)) examined by immunohistochemical analysis, significant levels of HSP70K561 dimethylation were observed in 354 cases (86.6%, Fig. 2d). Subsequently, we assessed the association of HSP70K561 dimethylation status with clinical outcome, and found that positive HSP70K561 dimethylation was observed in 82.4% of patients with cancer stage pT1 and 86.6% of pN0 patients, which indicates that the methylation levels may be elevated from an early stage in NSCLC carcinogenesis (Fig. 2e,f). We also found that HSP70K561 dimethylation status in NSCLC patients was significantly associated with the histological type adenocarcinoma (ADC) (P=0.0093; ADC versus non-ADC; Supplementary Table S4). Univariate analysis of association between prognosis and HSP70K561 dimethylation status demonstrated no statistical significance was observed (P=0.5219 by log-rank test; Supplementary Fig. S5); this might be due to the preponderance of HSP70K561 dimethylation up at an early stage of NSCLC.

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical analysis of K561 dimethylation of HSP70 in various cancer tissues.

(a,b) Immunohistochemical analysis of K561-dimethylated HSP70 levels in clinical tissue using anti-HSP70 K561me2 in bladder (a), lung (b) and kidney (c) cancer tissue microarrays. Detailed clinical information is described in Supplementary Tables S6, S7 and S8. (d) Immunohistochemical analysis of the K561 dimethylation status of HSP70 using a large number of NSCLC clinical tissues. Tissue sections were incubated with a rabbit anti-HSP70 K561me2 polyclonal antibody followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Dako). Three typical stained cases are shown. Staining intensity for each case is categorized into one of three patterns: 0 (no staining), 1 (weak staining), 2 (moderate to strong staining). (e,f) Distribution of K561 dimethylation status of HSP70 in NSCLC clinical tissues classified by the T-factor (e) and the N-factor (f).

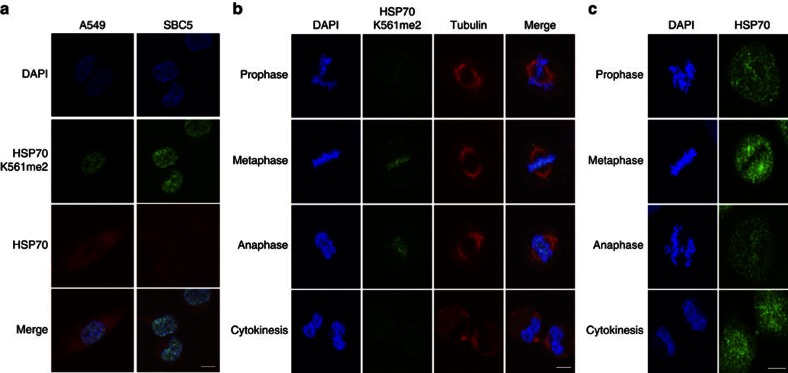

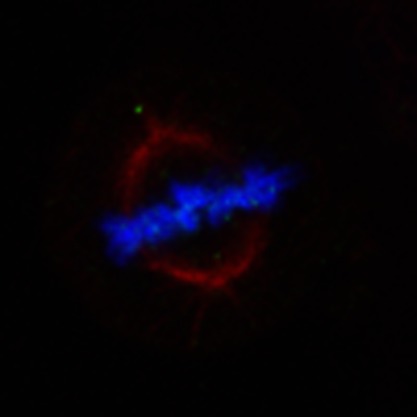

Methylated HSP70 is predominantly localized in the nucleus

To examine the biological significance of HSP70K561 dimethylation in human carcinogenesis, we conducted immunocytochemical analysis using two lung cancer cell lines, A549 and SBC5 (Fig. 3a). K561-dimethylated HSP70 proteins were predominantly localized in the nucleus, although the great majority of HSP70 protein was localized in the cytoplasm of cancer cells, suggesting that K561-dimethylated HSP70 might have a crucial role in the nucleus. Nuclear export of cytoplasmic hsp70s like yeast Ssa4p was reported to be independent of Xpo1/Crm1, but to be associated with Msn5p (the homologue of human XPO5), which is the exporter for Ssa4p from the nucleus15. Hence, to examine possible interactions between K561-dimethylated HSP70 and XPO5, or CRM1, we performed immunoprecipitation experiments using HSP70-WT and mutant HSP70 (HSP70-K561R), and found no differences between them (Supplementary Fig. S6). Interestingly, K561-dimethylated HSP70 was mainly localized on the chromosomes (Fig. 3b) even though the great majority of HSP70 protein was localized in the other intercellular region, especially cytoplasm (Fig. 3c, 90.09% at the metaphase plate; Supplementary Fig. S7), which implied that K561-dimethylated HSP70 might associate with a chromatin regulator in the nucleus.

Figure 3. Subcellular localization of K561-dimethylated HSP70.

(a) Immunocytochemical assays of K561-dimethylated HSP70 in A549 and SBC5 cell lines. Cells were co-stained with anti-HSP70 K561me2 (Alexa Fluor 488 (green)), anti-HSP70 (Alexa Fluor 594 (red)) antibodies and DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. (b,c) Subcellular localization of K561-dimethylated HSP70 (b) and general HSP70 (c) during mitosis in HeLa cells. Cells were treated with 7.5 μg ml−1 aphidicolin for 24 h to synchronize the cell cycle, and stained with anti-HSP70 K561me2, anti-HSP70 (Alexa Fluor 488 (green)), anti-tubulin (Alexa Fluor 594 (red)) antibodies and DAPI (blue) 12 h after release from cell cycle arrest. Scale bar, 10 μm.

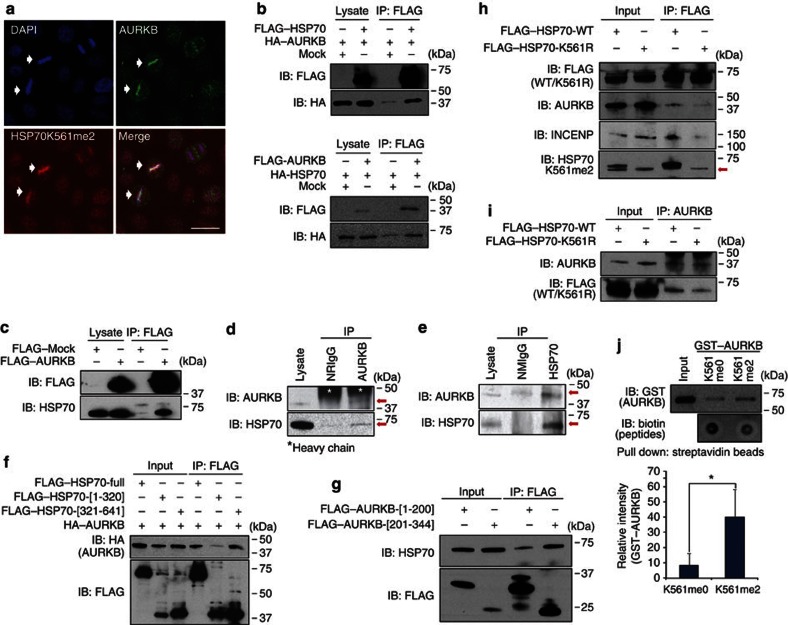

Methylated HSP70 interacts with AURKB

To search a critical binding partner(s) of K561-dimethylated HSP70, we immunoprecipitated K561-dimethylated HSP70 protein using antibodies against potential partners regulating chromatin function (Supplementary Table S5), and finally found AURKB to be an interacting partner of K561-dimethylated HSP70. AURKB is known for its involvement in phosphorylation of histone H3 at Ser 10 during mitosis16,17,18 and indeed, depletion of AURKB reduced the level of histone H3S10 phosphorylation during mitosis19. As shown in Fig. 4a, K561-dimethylated HSP70 and AURKB were concentrated on mitotic chromosome in HeLa cells. The immunoprecipitation assay demonstrated the interaction between HSP70 and AURKB proteins in exogenous level in 293T cells (Fig. 4b). This interaction was also confirmed between exogenous AURKB and endogenous HSP70 proteins in 293T cells (Fig. 4c), or endogenous AURKB and endogenous HSP70 proteins in cancer cells (Fig. 4d,e). These data indicate that AURKB and HSP70 appear to interact in cancer cells.

Figure 4. K561-dimethylated HSP70 interacts with AURKB in the nucleus.

(a) Cells were treated with 7.5 μg ml−1 of aphidicolin for 24 h to synchronize the cell cycle and stained with anti-HSP70 K561me2, anti-HSP70, anti-AURKB antibodies and DAPI 12 h after release from cell cycle arrest. Scale bar, 20 μm. (b) 293T cells were co-transfected with full-length HSP70 and AURKB expression vectors or a mock control vector. The interaction of FLAG–HSP70 with HA–AURKB (upper) or HA–HSP70 with FLAG–AURKB (bottom) was examined by immunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG M2 agarose and immunoblotted with anti-FLAG and anti-HA antibodies. (c) FLAG-mock and FLAG–AURKB expression vectors were transfected into 293T cells. After 48 h, cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG M2 agarose beads, and immunoprecipitants were immunoblotted with anti-FLAG and anti-HSP70 antibodies, respectively. (d) HeLa cells were lysed with CelLytic M and immunoprecipitated with normal rabbit IgG (NRIgG) and an anti-AURKB (ab2254, Abcam) antibody. The immunoprecipitates were fractionated by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-AURKB (ab2254, Abcam) and anti-HSP70 antibodies (SPA-810, Stressgen). (e) Cell lysates from A549 cells were immunoprecipitated with normal mouse IgG (NMIgG) and an anti-HSP70 (ADI-SPA-810, Enzo) antibody. The immunoprecipitates were fractionated by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-AURKB (no. 3094, Cell Signaling Technology) and anti-HSP70 (no. 4872, Cell Signaling Technology) antibodies. (f) 293T cells were co-transfected with an HA–AURKB expression vector and three different lengths of FLAG–HSP70 vectors (Supplementary Fig. S12). Immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-FLAG M2 agarose, and samples were immunoblotted with anti-FLAG and anti-HA antibodies. (g) 293T cells were transfected with two different lengths of FLAG–AURKB vectors (Supplementary Fig. S12). Immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-FLAG M2 agarose, and samples were immunoblotted with anti-FLAG and anti-HSP70 antibodies. (h,i) 293T cells were transfected with a wild-type FLAG-tagged HSP70 expression vector or a mutant FLAG-tagged HSP70 expression vector. Immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-FLAG M2 agarose (h) and anti-AURKB (i), and samples were immunoblotted with anti-FLAG, anti-AURKB, anti-INCENP and anti-HSP70 K561me2 antibodies. Red arrow indicates endogenous levels of dimethylated HSP70 K561. (j) In vitro pull-down assay. Signal intensity was quantified by Image J, and results represent the means±s.d. of four independent experiments. The P-value was calculated using Student's t-test (*P<0.05).

According to the experiment using deletion mutants of HSP70 and AURKB, the C-terminal portions of HSP70 and AURKB proteins are critical for their bindings (Fig. 4f,g). To examine the effect of K561 dimethylation of HSP70 on its binding affinity to AURKB, we immunoprecipitated HSP70-WT and K561-substituted HSP70 (HSP70-K561R), and found that the methylation level was significantly correlated with its binding affinity to AURKB protein (Fig. 4h,i). In addition, we examined the association between HSP70 and (inner centromere protein) INCENP, an AURKB binding partner in the chromosome passenger complex20, and found that K561 substituation significantly weakened the interaction between HSP70 and INCENP (Fig. 4h), implying that the methylation of HSP70 at K561 appears to be important for the interaction with INCENP as well as AURKB.

To further confirm the interaction between AURKB and HSP70 by an in vitro binding assay, we prepared K561-dimethylated HSP70 peptides and found that these peptides revealed significantly higher affinity to recombinant GST–AURKB than unmethylated HSP70 peptides (Fig. 4j), implying dimethylation of HSP70K561 to be essential for interaction with AURKB.

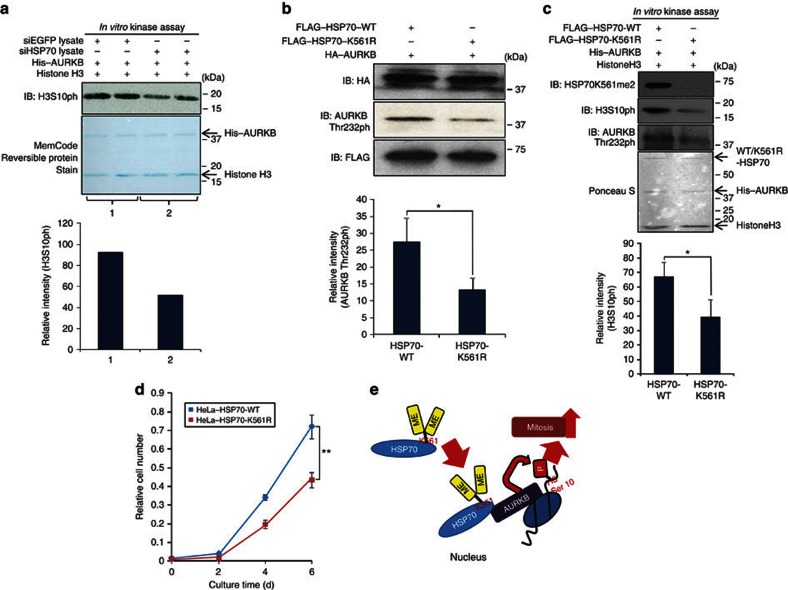

HSP70K561 methylation enhances AURKB activity

As the kinase activity of AURKB is known to be regulated by its binding partners21, we examined the effect of HSP70 interaction on its kinase activity. Reduction of cellular HSP70 protein in HeLa cells by treatment with specific HSP70 siRNA diminished phosphorylation of histone H3 at serine 10 (Supplementary Fig. S8a). An in vitro kinase assay showed that HSP70 enhanced the kinase activity of AURKB on histone H3 (Fig. 5a; Supplementary Fig. S8b). Taken together, AURKB activity is likely to be regulated by the association with HSP70. Yasui et al.22 previously reported that autophosphorylation of AURKB at Thr 232 is an essential regulatory mechanism for its kinase activity and cytokinesis. To clarify the importance of HSP70 methylation for the cell cycle progression of cancer cells, we examined the effect of K561-dimethylated HSP70 on the phosphorylation status of AURKB at Thr 232. We transfected an HSP70-WT or a mutant HSP70 (HSP70-K561R) expression vector, and a full-length AURKB expression vector into 293T cells, and found that AURKB autophosphorylation levels were significantly low when co-transfected with mutant HSP70, compared with the case when co-transfected with HSP70-WT (Fig. 5b). This result suggests that dimethylation of HSP70-K561 has a critical role in regulation of AURKB autophosphorylation. To further elucidate the cellular mechanism, we performed in vitro kinase assays using immunoprecipitants expressed in 293T cells and detected that HSP70-WT enhanced AURKB-dependent phosphorylation of histone H3, compared with HSP70-K561R, and the difference was quantitatively significant (P<0.05, Student's t-test; Fig. 5c). So far, AURKB has been considered as an important regulator of mitosis and deregulation of this enzyme in various types of cancer was reported23,24. Therefore, we examined the effect of K561 dimethylation of HSP70 on the AURKB activity and the proliferation of cancer cells. We constructed HeLa transfectants stably overexpressing HSP70-WT or HSP70-K561R, and examined the endogenous AURKB kinase activity (Supplementary Fig. S9). The HeLa cells with HSP70-WT showed higher AURKB activity than those with HSP70-K561R. Cell growth analysis demonstrated that HSP70-K561R (unmethylated) transfectants showed slower growth rates than HSP70-WT transfectants (Fig. 5d), and this was confirmed using A549-stable transformants (Supplementary Fig. S10). Furthermore, to exclude the effect of endogenous HSP70 proteins, we further conducted the functional analysis using siRNA-resistant HSP70-WT and HSP70-K561R expression vectors. We transfected each of these vectors into HeLa cells, after depletion of endogenous HSP70, and conducted a clonogenicity assay. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S11, HSP70-K561R-overexpressing cells showed significant reduced cell proliferation, compared with HSP70-WT-overexpressing cells. This result further supported the importance of K561 methylation on HSP70 in human carcinogenesis. Together, our results imply that K561 dimethylation of HSP70 has a critical role in the cell cycle progression and growth of cancer cells by regulating AURKB kinase activity.

Figure 5. K561 dimethylation of HSP70 enhances AURKB kinase activity.

(a) HeLa cells were lysed with CelLytic M Cell Lysis Reagent 48 h after treatment with siEGFP (control) or siHSP70. Cell lysates were mixed with His–AURKB enzyme and histone H3 substrate in the reaction buffer and incubated for 10 min at 30 °C; then the mixture was immunoblotted with an anti-phospho-histone H3 (Ser 10) antibody. His–AURKB and histone H3 proteins used in the reaction were visualized by MemCode Reversible Protein Stain (Thermo Scientific), and signal intensity was quantified by Image J. (b) An HA–AURKB expression vector and a wild-type HSP70 (HSP70-WT) vector or a mutant HSP70 vector were co-transfected into 293T cells. Immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-HA agarose, and samples were immunoblotted with anti-HA and anti-phospho-Thr-232 AURKB antibodies. Signal intensity was quantified by Image J. Results are shown as the means±s.d. of three independent experiments, and the P-value was calculated using Student's t-test (*P<0.05). (c) A FLAG–HSP70-WT expression vector or a FLAG–HSP70-K561R expression vector was transfected into 293T cells, and immunoprecipitation was conducted using anti-FLAG M2 agarose. FLAG–HSP70-WT or FLAG–HSP70-K561R proteins were mixed with his–AURKB as an enzyme and histone H3 as a substrate in the reaction buffer, and incubated for 10 min at 30 °C. Immunoblot analysis was conducted with an anti-HSP70 K561me2, anti-phospho-histone H3 (Ser 10) and anti-phospho-Thr-232 AURKB antibodies. FLAG–HSP70-WT, FLAG–HSP70-K561R, His–AURKB and histone H3 proteins used in the reaction were visualized with Ponceau S. Signal intensity was quantified using Image J, and results represent the means±s.d. of three independent experiments. The P-value was calculated using Student's t-test (*P<0.05). (d) Cell growth assay of HSP70-WT or HSP70-K561R stable cell lines. Number of cells was measured by Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo). Results are the means±s.d. of three independent experiments. P-values were calculated using Student's t-test (**P<0.01). (e) Model for K561-dimethylated HSP70-mediated cell cycle regulation in cancer cells.

Discussion

In the present study, K561-dimethylated HSP70 is shown to be significantly increased in various types of cancer. K561-dimethylated HSP70 protein is localized to the nucleus, whereas unmethylated HSP70 is predominantly localized in the cytoplasm. K561-dimethylated HSP70 preferentially interacts with AURKB and regulates its kinase activity in the nucleus. Taken together, it is probable that elevated K561-dimethylated HSP70 in cancer cells promotes cell cycle progression through activation of AURKB (Fig. 5e). In our study, we identified three roles for lysine methylation in the non-histone protein HSP70. First, lysine methylation controls the subcellular localization of protein. In the nucleus, methylated HSP70 tightly interacts with AURKB, a major component of the chromosomal passenger complex (CPC)18. The CPC, upon entry into mitosis, is first localized to both chromosome arms and the inner centromere, a region located between sister kinetochores. As the cell cycle progresses to metaphase, the amount of CPC localized to the chromosome arms decreases and it is mainly detected at the inner centromere25. As methylated HSP70 clearly colocalized with AURKB (Fig. 4a), it may be involved in the CPC and regulate its functions through interaction with AURKB. In addition, our data have indicated that HSP70 methylation also affects the interaction with INCENP, which is critical for the CPC assembles26. The INCENP C terminus binds to AURKB through the IN-box and enhances the kinase activity. Subsequently, AURKB-dependent phosphorylation of a TSS motif near the INCENP C terminus leads to full kinase activation of AURKB through a feedback mechanism27. Therefore, it is possible that methylated HSP70 might regulate the AURKB activity through the interaction between AURKB and INCENP. Taken together, these data provide clear evidence that lysine methylation can regulate the protein subcellular localization and the function of binding partners. Second, we showed the possibility that dimethylation of HSP70 is indicated as a biomarker for cancer diagnosis or cancer prognosis. Although it has been validated to use histone methylation status as a biomarker of cancer28,29,30, this is the first evaluation of the methylation status of a non-histone protein as an indicator of cancer. We found that 86.6% of NSCLC cases with elevated K561 HSP70 dimethylation in 409 individual NSCLC tissues examined (Fig. 2d) and that K561 dimethylation levels are significantly associated with male gender and histological type (Supplementary Table S4). Large-scale validation of the present results may lead to the development of novel diagnostic or prognostic methods of human cancer. Third, and more importantly, we identified K561-dimethylated HSP70 as an important regulator of AURKB kinase activity in cancer cells. Deregulation of AURKB has been reported in various types of cancer31,32, and AURKB has been used as a target for cancer therapy33. Our findings reveal a potential molecular mechanism for AURKB dysfunction in human carcinogenesis. HSP70 and SETD1A have also been counted as potential target molecules for cancer therapy34,35,36. It is possible that combination therapy of an AURKB inhibitor and an HSP70 inhibitor, or an AURKB inhibitor and some specific methylation inhibitors might reinforce current strategies for cancer therapy targeting AURKB.

Methods

Cell culture

All cell lines were grown in monolayers in appropriate media: DMEM for COS7 and 293T cells; Eagle's MEM for WI-38, IMR-90, MRC5, CCD-18Co, SCaBER and SBC5 cells; McCoy's 5A medium for HCT116 cell; RPMI1640 medium for A549, ACC-LC-319 and SNU475 cells supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. SAEC cells were maintained in small-airway epithelial cell basal medium supplemented with 52 μg ml−1 bovine pituitary extract, 0.5 ng ml−1 human recombinant epidermal growth factor, 0.5 μg ml−1 hydrocortisone, 0.5 μg ml−1 epinephrine, 10 μg ml−1 transferrin, 5 μg ml−1 insulin, 0.1 ng ml−1 retinoic acid, 6.5 ng ml−1 triiodothyronine, 50 μg ml−1 gentamicin/amphotericin-B (GA-1000) and 50 μg ml−1 fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin. All cells were maintained at 37 °C in humid air with 5% CO2 condition. Cells were transfected with FuGENE6 (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's protocol37,38.

Selection criteria of cell lines

The selection criteria for cell lines used in this study are as follows: for knockdown experiments, we used HeLa cells where HSP70 is highly methylated and SETD1A is highly expressed. We used 293T cells for experiments that required high transfection efficiency, including gain-of-function experiments, and where the exogenous HSP70-WT is highly methylated. We used COS7 cells for experiments that required a high level of HSP70 methylation in response to the exogenous stimulus such as overexpression of SETD1A. We used the A549 and SBC5 cancer cell lines in addition to HeLa cells to validate the data.

Antibodies

The following primary antibodies were deployed; anti-FLAG (M2; Sigma-Aldrich; dilution used in WB: 1:1000), anti-HA (Y-11; Santa Cruz; dilution used in WB: 1:500), anti-Histone H3 (ab1791; Abcam; dilution used in WB: 1:500), anti-pan methyl lysine (dilution used in WB: 1:500)14, anti-phospho-H3 (Ser 10; no. 9706; Cell Signaling; dilution used in WB: 1:500), anti-CRM1 (H-300; Santa Cruz; dilution used in WB: 1:500), anti-XPO5 (H-300; Santa Cruz; dilution used in WB: 1:500), anti-GST (B-14; Santa Cruz; dilution used in WB: 1:500), anti-HSP70 (SPA-810; Stressgen; dilution used in WB: 1:500), anti-phospho-Aurora B (Thr 232; no. 2914; Cell Signaling; dilution used in WB: 1:500), anti-SETD1A (HPA020646; Sigma-Aldrich; dilution used in WB: 1:100, immunohistochemistry: 1:200), anti-ACTB (sc-1616; Santa Cruz; dilution used in WB: 1:500), anti-INCENP (39-2800; Invitrogen; dilution used in WB: 1:500) and anti-Tubulin (B7; Santa Cruz; dilution used in immunocytochemistry: 1:500). The anti-K561-dimethylated HSP70 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich; dilution used in WB: 1:500, immunohistochemistry: 1:2000) was produced in rabbit immunized with a synthetic peptide.

Mass spectrometry

C-terminal HA-tagged human HSP70 was expressed in 293T cells and purified with anti-HA antibody (clone no. MMS-101R; BAbCO) plus protein A/G agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's protocol. A corresponding band was excised from SDS–PAGE after electrophoresis. Proteins in the gel piece were reduced with dithiothreitol, carbamido—methylated with iodoacetamide and digested with modified trypsin—(Promega) at 37 °C overnight. The tryptic peptides were then applied to an LC-MS/MS system. Chromatographic separation was accomplished on the MAGIC 2002 HPLC system (Michrom BioResources, Inc., Auburn, CA, USA). Peptide samples were loaded onto a Cadenza C18 custom-packed column (0.2×50 mm; Michrom BioResources, Inc.), in which Cadenza CD-C18 resin (Imtakt Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) was packed and eluted using a linear gradient of 5–60% CH3CN in 0.1% HCOOH in 30 min with a flow-rate of 1 μl min−1. Samples were sequentially ionized with Nanoflow-LC ESI, and the LCQ-Deca XP ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corp., USA) was used to obtain MS/MS spectral data. Methylation was screened using the Mascot database-searching software (Matrix Science, Inc., London, UK). The mass spectrometry identified 348 tryptic peptides, which cover 77% of full-length human HSP70 protein.

Lung tissue samples for tissue microarray

Primary NSCLC tissue samples, as well as their corresponding normal tissues, adjacent to resection margins from patients having no anti-cancer treatment before tumour resection had been obtained earlier with informed consent39,40,41. All tumours were staged on the basis of the pathological tumour node metastasis classification of the International Union Against Cancer. Formalin-fixed primary lung tumours and adjacent normal lung tissue samples used for immunostaining on tissue microarrays had been obtained from 409 patients undergoing curative surgery at Saitama Cancer Center (Saitama, Japan)42,43. To be eligible for this study, tumour samples were selected from patients who fulfilled all of the following criteria: patients suffered primary NSCLC with a histologically confirmed stage (only pT1–pT3, pN0–pN2, and pM0); patients underwent curative surgery, but did not receive any preoperative treatment; among them, NSCLC patients with positive lymph node metastasis (pN1, pN2) were treated with platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapies after surgical resection, whereas patients with pN0 did not receive adjuvant chemotherapies; and patients whose clinical follow-up data were available. This study and the use of all clinical materials mentioned were approved by individual institutional ethics committees.

Immunohistochemical analysis

The K561 dimethylation status of HSP70 in clinical tissues were examined by immunohistochemical analysis44,45,46,47,48. EnVision+ kit/horseradish peroxidase kit (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) was applied, and slides of paraffin-embedded lung tumour specimens were processed under high pressure (125 °C, 30 s) in antigen-retrieval solution, high pH 9 (S2367, Dako), treated with peroxidase blocking reagent, and then treated with protein blocking reagent (K130, X0909, Dako). Tissue sections were incubated with a rabbit anti-HSP70 K561me2 polyclonal antibody followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Dako). Antigen was visualized with substrate chromogen (Dako liquid DAB chromogen; Dako). Finally, tissue specimens were stained with Mayer haematoxylin (Hematoxylin QS; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 20 s to discriminate the nucleus from the cytoplasm. Three independent investigators semi-quantitatively assessed HSP70 positivity without prior knowledge of clinicopathological data. The intensity of HSP70 staining was evaluated using the following criteria: strong positive (scored as 2+), brown staining in >50% of tumour cells completely obscuring cytoplasm; weak positive (1+), any lesser degree of brown staining appreciable in tumour cell cytoplasm; and absent (scored as 0), no appreciable staining in tumour cells. Cases were accepted as strongly positive if two or more investigators independently defined them as such. Detailed clinical information of bladder, lung and kidney tissues are described in Supplementary Tables S6–S8.

siRNA transfection

siRNA oligonucleotide duplexes were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich for targeting the human HSP70 transcript. siEGFP was used as control siRNA. The siRNA sequences are described in Supplementary Table S9. siRNA duplexes (100 nM final concentration) were transfected into bladder and lung cancer cell lines with Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies)49,50,51.

Immunoprecipitation

Transfected 293T cells or SBC5 cells were lysed with CelLytic M Cell Lysis Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) containing a complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science). In a typical immunoprecipitation reaction, 300 μg of whole-cell extract was incubated with an optimum concentration of primary antibody. After the beads had been washed three times in 1 ml of Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.6), proteins that bound to the beads were eluted by boiling in Lane Marker Reducing Sample Buffer (Thermo Scientific). The HSP70 and AURKB constructs used for the immunoprecipitation are described in Supplementary Fig. S12.

Western blot

Samples were prepared from the cells lysed with CelLytic M buffer, and whole-cell lysates or immunoprecipitation (IP) products were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Protein bands were detected by incubating with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) and visualizing with Enhanced Chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare).

Immunocytochemistry

Cultured cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at room temperature for 30 min, permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma) in PBS for 3 min and blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 30 min. Fixed cells were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C and stained by Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Life Technologies). Fluorescent images were obtained using a TCS SP2 AOBS microscope (Leica Mycrosystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

In vitro pull-down assay

Biotin-tagged methylated HSP70 peptide (Biotin-VKKKDAESI[di-me-K]GKLGEDE) or biotin-tagged unmethylated HSP70 peptide (Biotin-VKKKDAESIKGKLGEDE) with recombinant GST-AURKB proteins. Five micrograms of peptides and 1 μg of GST-AURKB proteins were pre-incubated in Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.5) for 12 h. Immunoprecipitaion was conducted using streptavidin beads, and samples were detected with an anti-GST antibody by immunoblot and an horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-biotin antibody by dot blot.

In vitro kinase assay

One microgram of recombinant his-AURKB (in house) proteins was incubated with 1 μg purified histone H3 (Millipore) with HSP70-WT (1 μg) or mutant HSP70-K561R (1 μg) immunoprecipitants for 10 min at 30 °C in the reaction buffer (40 mM MOPS (pH7.0). and 1 mM EDTA). The reaction mixture was fractionated by SDS–PAGE.

Clonogenicity assays

HEK293 cells, cultured in DMEM 10% fetal bovine serum, were transfected with a FLAG-siRes-WT-HSP70 vector or a FLAG-siRes-K561R-HSP70 vector after treatment with siHSP70 for 24 h. The transfected HEK293 cells were cultured for 1 day and seeded in 10-cm dish at the density of 10,000 cells per 10-cm dish in triplicate. Subsequently, the cells were cultured in DMEM 10% fetal bovine serum containing 0.9 (mg ml−1) Geneticin/G-418 for 2 weeks until colonies were visible. Colonies were stained with Giemsa (Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA) and counted by Colony Counter software.

Author contributions

H.-S.C., T.S., A.I., M.Y., Y.N. and R.H. designed this study and performed all experiments with the help of G.T., S.H., N.I. and K.M.; Y.D. and E.T. performed immunohistochemical analysis. H.-S.C., T.S. and R.H. wrote this manuscript; and Y.M., H.I.F., S.O., B.A.J.P., M.Y. and Y.N. critically read the manuscript and gave good advices. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Cho, H.-S., et al. Enhanced HSP70 lysine methylation promotes proliferation of cancer cells through activation of Aurora kinase B. Nat. Commun. 3:1072 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2074 (2012).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1-S12 and Supplementary Tables S1-S9

Acknowledgments

We thank Kazuhiro Maejima, Yuka Yamane, Yukiko Iwai and Haruka Sawada for technical assistance. This work was supported by a Grant-in Aid for Young Scientists (A) (22681030) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

References

- Clarke S. G. & Tamanoi F. Protein Methyltransferases. The Enzymes Vol. XXIV, 3rd Edn. (Academic Press, San Diego, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Bedford M. T. & Clarke S. G. Protein arginine methylation in mammals: who, what, and why. Mol. Cell. 33, 1–13 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride A. E. & Silver P. A. State of the arg: protein methylation at arginine comes of age. Cell 106, 5–8 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachner M. & Jenuwein T. The many faces of histone lysine methylation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14, 286–298 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuikov S. et al. Regulation of p53 activity through lysine methylation. Nature 432, 353–360 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J. et al. Repression of p53 activity by Smyd2-mediated methylation. Nature 444, 629–632 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H. S. et al. Demethylation of RB regulator MYPT1 by histone demethylase LSD1 promotes cell cycle progression in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 71, 1–6 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunizaki M. et al. The lysine 831 of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 is a novel target of methylation by SMYD3. Cancer Res. 67, 10759–10765 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampinga H . H. & Craig E. A. The HSP70 chaperone machinery: J proteins as drivers of functional specificity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 579–592 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinez C., Losfeld M. E., Cacan R., Michalski J. C. & Lefebvre T. Modulation of HSP70 GlcNAc-directed lectin activity by glucose availability and utilization. Glycobiology 16, 22–28 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar Y. & Tatu U. Stress protein flux during recovery from simulated ischemia: induced heat shock protein 70 confers cytoprotection by suppressing JNK activation and inhibiting apoptotic cell death. Proteomics 3, 513–526 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore D. J., West A. B., Dikeman D. A., Dawson V. L. & Dawson T. M. Parkin mediates the degradation-independent ubiquitination of Hsp70. J. Neurochem. 105, 1806–1819 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller P. et al. C-terminal phosphorylation of Hsp70 and Hsp90 regulates alternate binding to co-chaperones CHIP and HOP to determine cellular protein folding/degradation balances. Oncogene (e-pub ahead of print 23 July 2012; doi:10.1038/onc.2012.314). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwabata H., Yoshida M. & Komatsu Y. Proteomic analysis of organ-specific post-translational lysine-acetylation and -methylation in mice by use of anti-acetyllysine and -methyllysine mouse monoclonal antibodies. Proteomics 5, 4653–4664 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan X., Tsoulos P., Kuritzky A., Zhang R. & Stochaj U. The carrier Msn5p/Kap142p promotes nuclear export of the hsp70 Ssa4p and relocates in response to stress. Mol. Microbiol. 62, 592–609 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosio C. et al. Mitotic phosphorylation of histone H3: spatio-temporal regulation by mammalian Aurora kinases. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 874–885 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigent C. & Dimitrov S. Phosphorylation of serine 10 in histone H3, what for? J. Cell. Sci. 116, 3677–3685 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vader G., Medema R. H. & Lens S. M. The chromosomal passenger complex: guiding Aurora-B through mitosis. J. Cell. Biol. 173, 833–837 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu J. Y. et al. Mitotic phosphorylation of histone H3 is governed by Ipl1/aurora kinase and Glc7/PP1 phosphatase in budding yeast and nematodes. Cell 102, 279–291 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaprakash A. A. et al. Structure of a Survivin-Borealin-INCENP core complex reveals how chromosomal passengers travel together. Cell 131, 271–285 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruchaud S., Carmena M. & Earnshaw W. C. Chromosomal passengers: conducting cell division. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 798–812 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui Y. et al. Autophosphorylation of a newly identified site of Aurora-B is indispensable for cytokinesis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 12997–13003 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lens S. M., Voest E. E. & Medema R. H. Shared and separate functions of polo-like kinases and aurora kinases in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 825–841 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vader G. & Lens S. M. The Aurora kinase family in cell division and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1786, 60–72 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardmore V. A., Ahonen L. J., Gorbsky G. J. & Kallio M. J. Survivin dynamics increases at centromeres during G2/M phase transition and is regulated by microtubule-attachment and Aurora B kinase activity. J. Cell. Sci. 117, 4033–4042 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke C. A., Heck M. M. & Earnshaw W. C. The inner centromere protein (INCENP) antigens: movement from inner centromere to midbody during mitosis. J. Cell. Biol. 105, 2053–2067 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda R., Korner R. & Nigg E. A. Exploring the functional interactions between Aurora B, INCENP, and survivin in mitosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 3325–3341 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellinger J. et al. Prognostic relevance of global histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methylation in renal cell carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 127, 2360–2366 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsheikh S. E. et al. Global histone modifications in breast cancer correlate with tumor phenotypes, prognostic factors, and patient outcome. Cancer Res. 69, 3802–3809 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligson D. B. et al. Global histone modification patterns predict risk of prostate cancer recurrence. Nature 435, 1262–1266 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meraldi P., Honda R. & Nigg E. A. Aurora kinases link chromosome segregation and cell division to cancer susceptibility. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14, 29–36 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama H., Brinkley W. R. & Sen S. The Aurora kinases: role in cell transformation and tumorigenesis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 22, 451–464 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lok W., Klein R. Q. & Saif M. W. Aurora kinase inhibitors as anti-cancer therapy. Anticancer Drugs 21, 339–350 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi L., Giordanetto F. & Kroemer G. Targeting HSP70 for cancer therapy. Mol. Cell 36, 176–177 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. et al. Characterization of a novel mechanism of genomic instability involving the SEI1/SET/NM23H1 pathway in esophageal cancers. Cancer Res. 70, 5695–5705 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav S., Singhal J., Singhal S. S. & Awasthi S. hSET1: a novel approach for colon cancer therapy. Biochem. Pharmacol. 77, 1635–1641 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamoto R. et al. SMYD3 encodes a histone methyltransferase involved in the proliferation of cancer cells. Nat. Cell. Biol. 6, 731–740 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamoto R. et al. Enhanced SMYD3 expression is essential for the growth of breast cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 97, 113–118 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T. et al. A novel human tRNA-dihydrouridine synthase involved in pulmonary carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 65, 5638–5646 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi T. et al. Expression profiles of non-small cell lung cancers on cDNA microarrays: identification of genes for prediction of lymph-node metastasis and sensitivity to anti-cancer drugs. Oncogene 22, 2192–2205 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniwaki M. et al. Gene expression profiles of small-cell lung cancers: molecular signatures of lung cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 29, 567–575 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa N. et al. ADAM8 as a novel serological and histochemical marker for lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 8363–8370 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa N. et al. Cancer-testis antigen lymphocyte antigen 6 complex locus K is a serologic biomarker and a therapeutic target for lung and esophageal carcinomas. Cancer Res. 67, 11601–11611 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H. S. et al. Enhanced expression of EHMT2 is involved in the proliferation of cancer cells through negative regulation of SIAH1. Neoplasia 13, 676–684 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takawa M. et al. Validation of the histone methyltransferase EZH2 as a therapeutic target for various types of human cancer and as a prognostic marker. Cancer Sci. 102, 1298–1305 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyokawa G. et al. The histone demethylase JMJD2B plays an essential role in human carcinogenesis through positive regulation of cyclin-dependent kinase 6. Cancer Prev. Res. 4, 2051–61 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyokawa G. et al. The histone lysine methyltransferase Wolf-Hirschhorn Syndrome Candidate 1 Is Involved in human carcinogenesis through regulation of the Wnt pathway. Neoplasia 13, 887–898 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyokawa G. et al. Minichromosome Maintenance Protein 7 is a potential therapeutic target in human cancer and a novel prognostic marker of non-small cell lung cancer. Mol. Cancer 10, 65 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayami S. et al. Overexpression of LSD1 contributes to human carcinogenesis through chromatin regulation in various cancers. Int. J. Cancer 128, 574–586 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayami S. et al. Overexpression of the JmjC histone demethylase KDM5B in human carcinogenesis: involvement in the proliferation of cancer cells through the E2F/RB pathway. Mol. Cancer 9, 59 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimatsu M. et al. Dysregulation of PRMT1 and PRMT6, Type I arginine methyltransferases, is involved in various types of human cancers. Int. J. Cancer 128, 562–573 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1-S12 and Supplementary Tables S1-S9