Abstract

Recent years have witnessed the introduction of several high-quality review articles into the literature covering various scientific and technical aspects of bioanalysis. Now it is widely accepted that bioanalysis is an integral part of the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic characterization of a novel chemical entity from the time of its discovery and during various stages of drug development, leading to its market authorization. In this compilation, the important bioanalytical parameters and its application to drug discovery and development approaches are discussed, which will help in the development of safe and more efficacious drugs with reduced development time and cost. It is intended to give some general thoughts in this area which will form basis of a general framework as to how one would approach bioanalysis from inception (i.e., discovery of a lead molecule) and progressing through various stages of drug development.

Keywords: Bioanalytical, method validation, metabolism, pharmacokinetics, toxicokinetic

INTRODUCTION

The discovery and development of a new drug costs around $1 billion and it may take approximately 10 years for the drug to reach the marketplace.[1] Drug discovery and development is the process of generating compounds and evaluating all their properties to determine the feasibility of selecting one novel chemical entity (NCE) to become a safe and efficacious drug. Strategies in the drug discovery and drug development processes are undergoing radical change. For example, the contribution of pharmacokinetics (PK) to both processes is increasing.[2,3] Furthermore, toxicokinetics has now become established as an essential part of toxicity testing.[4,5] With this emphasis in the use of PK/toxicokinetics and the greater potencies of newer drugs, a sensitive and specific bioanalytical technique is essential.

The emergence of the field of bioanalysis as a critical tool during the process of drug discovery and development is well understood and globally accepted.[6–9] Over the past few decades, a plethora of assays has been continuously developed for NCEs to support various stages of discovery and development, including assays for important metabolites.[10–14] Additionally, multiple analytical procedures are available for prescription medicines (Rx) and/or generic products.[15–23] Bioanalytical data generated in discovery and pre-clinical programs are a valuable guide to early clinical programs. Plasma concentration-response data from these programs can be compared with those obtained in man. Such comparisons are particularly valuable during the phase one-initial dose escalation study. To maximize this, it is our practice to generate PK data between each dose increase.[24]

BIOANALYSIS

Bioanalysis is a term generally used to describe the quantitative measurement of a compound (drug) or their metabolite in biological fluids, primarily blood, plasma, serum, urine or tissue extracts.[25] A bioanalytical method consists of two main components

Sample preparation: Sample preparation is a technique used to clean up a sample before analysis and/or to concentrate a sample to improve its detection. When samples are biological fluids such as plasma, serum or urine, this technique is described as bioanalytical sample preparation. The determination of drug concentrations in biological fluids yields the data used to understand the time course of drug action, or PK, in animals and man and is an essential component of the drug discovery and development process.[26] Most bioanalytical assays have a sample preparation step to remove the proteins from the sample. Protein precipitation, liquid–liquid extraction and solid phase extraction (SPE) are routinely used.[27]

Detection of the compound: The detector of choice is a mass spectrometer.[26] Currently, the principle technique used in quantitative bioanalysis is high performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) using either electrospray ionization (ESI) or atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) techniques.[28] The triple quadrupole (QqQ) mass spectrometer (MS), when operated in the selected reaction monitoring (SRM) mode, offers a unique combination of sensitivity, specificity and dynamic range. Consequently, the QqQ MS has become the instrument of choice for quantitation within the pharmaceutical industry. Since ESI and APCI can be operated at flow rates as high as 1 and 2 mL/min, respectively, most of the convenience columns (e.g., C18, C8, C4, phenyl, cyanopropyl) are compatible. Recent technological advances have made 1.7 μm particle size packing material available. Coupling with high pressure pump and high-speed acquisition MS, ultra-high pressure liquid chromatography (UPLC) offers unique high-throughput and resolving power to obtain maximum chromatographic performance and superior assay sensitivity.[29]

Before a bioanalytical method can be implemented for routine use, it is widely recognized that it must first be validated to demonstrate that it is suitable for its intended purpose. A GLP (Good Laboratory Practices) validated bioanalytical method is needed to support all development studies (e.g., toxicology studies and human clinical trials). According to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) GLP guidance,[30] there is a general agreement that at least the following validation parameters should be evaluated for quantitative procedures: selectivity, calibration model, stability, accuracy (bias, precision) and limit of quantification. Additional parameters which might have to be evaluated include limit of detection (LOD), recovery, reproducibility and ruggedness (robustness).[31–33] Validation involves documenting, through the use of specific laboratory investigations, that the performance characteristics of the method are suitable and reliable for the intended analytical applications. The acceptability of analytical data corresponds directly to the criteria used to validate the method.[34]

In early stages of drug development, it is usually not necessary to perform all of the various validation studies. Many researchers focus on specificity, linearity and precision studies for drugs in preclinical through Phase II (preliminary efficacy) stages. The remaining studies penetrating validation are performed when the drug reaches the Phase II (efficacy) stage of development and has a higher probability of becoming a marketed product. Presently, Guidelines for pharmaceutical methods in United States pharmacopoeia (USP), International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) and FDA provide a framework for regulatory submission must include study on such fundamental parameters.

Validation parameters

There is a general agreement that at least the following validation parameters should be evaluated for quantitative procedures: selectivity, calibration model, stability, accuracy (bias, precision) and limit of quantification. Additional parameters which might have to be evaluated include LOD, recovery, reproducibility and ruggedness (robustness).

Specificity/selectivity

A method is specific if it produces a response for only one single analyte. Since it is almost impossible to develop a chromatographic assay for a drug in a biological matrix that will respond to only the compound of interest, the term selectivity is more appropriate. The selectivity of a method is its ability to produce a response for the target analyte which is distinguishable from all other responses (e.g., endogenous compounds such as protein, amino acids, fatty acids, etc).[35]

Accuracy

Accuracy of an analytical method describes the closeness of mean test results obtained by the method to the true value (concentration) of the analyte. This is sometimes termed as trueness. The two most commonly used ways to determine the accuracy or method bias of an analytical method are (i) analyzing control samples spiked with analyte and (ii) by comparison of the analytical method with a reference method.[36]

Precision

It is the closeness of individual measures of an analyte when the procedure is applied repeatedly to multiple aliquots of a single homogenous volume of biological matrix.[30] There are various parts to precision, such as repeatability, intermediate precision, and reproducibility (ruggedness). Repeatability means how the method performs in one lab and on one instrument, within a given day. Intermediate precision refers to how the method performs, both qualitatively and quantitatively, within one lab, but now from instrument-to-instrument and from day-to-day. Finally, reproducibility refers to how that method performs from lab-to-lab, from day-to-day, from analyst-to-analyst, and from instrument-to-instrument, again in both qualitative and quantitative terms.[35,36] The duration of these time intervals is not defined. Within/intraday, - assay, -run and -batch are commonly used to express the repeatability. Expressions for reproducibility of the analytical method are between interday, -assay, -run and -batch. The expressions intra/within-day and inter/between-day precision are not preferred because a set of measurements could take longer than 24 hours or multiple sets could be analyzed within the same day.[37]

Detection limit

The LOD is the lowest concentration of analyte in the sample that can be detected but not quantified under the stated experimental conditions.[37] The LOD is also defined as the lowest concentration that can be distinguished from the background noise with a certain degree of confidence. There is an overall agreement that the LOD should represent the smallest detectable amount or concentration of the analyte of interest.

Quantitation limit

The quantitation limit of individual analytical procedures is the lowest amount of analyte in a sample, which can be quantitatively determined with suitable precision and accuracy.

Linearity

According to the ICH definition, “the linearity of an analytical procedure is its ability (within a given range) to obtain test results which are directly proportional to the concentration (amount) of analyte in the sample”. The concentration range of the calibration curve should at least span those concentrations expected to be measured in the study samples. If the total range cannot be described by a single calibration curve, two calibration ranges can be validated. It should be kept in mind that the accuracy and precision of the method will be negatively affected at the extremes of the range by extensively expanding the range beyond necessity. Correlation coefficients were most widely used to test linearity. Although the correlation coefficient is of benefit for demonstrating a high degree of relationship between concentration and response data, it is of little value in establishing linearity.[38] Therefore, by assessing an acceptable high correlation coefficient alone the linearity is not guaranteed and further tests on linearity are necessary, for example, a lack-of-fit test.

Range

The range of an analytical procedure is the interval between the upper and lower concentration (amounts) of analyte in the sample (including these concentrations) for which it has been demonstrated that the analytical procedure has a suitable level of precision, accuracy and linearity.[30]

Robustness

It is the measure of its capacity to remain unaffected by small, but deliberate, variations in method parameters and provides an indication of its reliability during normal usage.

Extraction recovery

It can be calculated by comparison of the analyte response after sample workup with the response of a solution containing the analyte at the theoretical maximum concentration. Therefore, absolute recoveries can usually not be determined if the sample workup includes a derivatization step, as the derivatives are usually not available as reference substances.

Stability

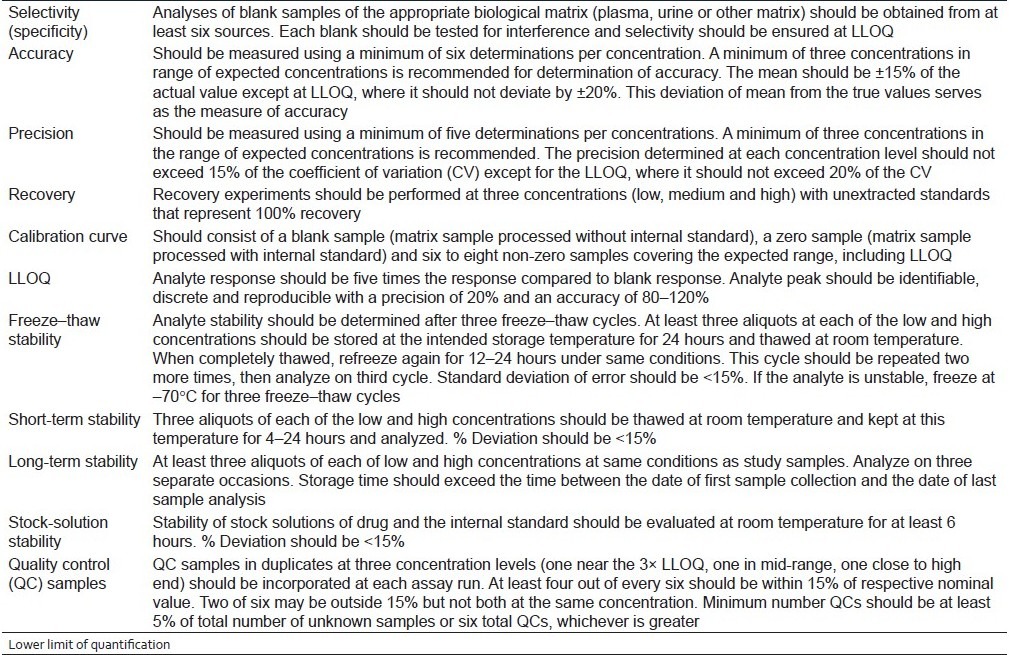

It is the chemical stability of an analyte in a given matrix under specific conditions for given time intervals.[30] The aim of a stability test is to detect any degradation of the analyte(s) of interest during the entire period of sample collection, processing, storing, preparing, and analysis.[39] All but long-term stability studies can be performed during the validation of the analytical method. Long-term stability studies might not be complete for several years after clinical trials begin. The condition under which the stability is determined is largely dependent on the nature of the analyte, the biological matrix, and the anticipated time period of storage (before analysis). The ICH guidelines are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

US FDA guidelines for bioanalytical method validation

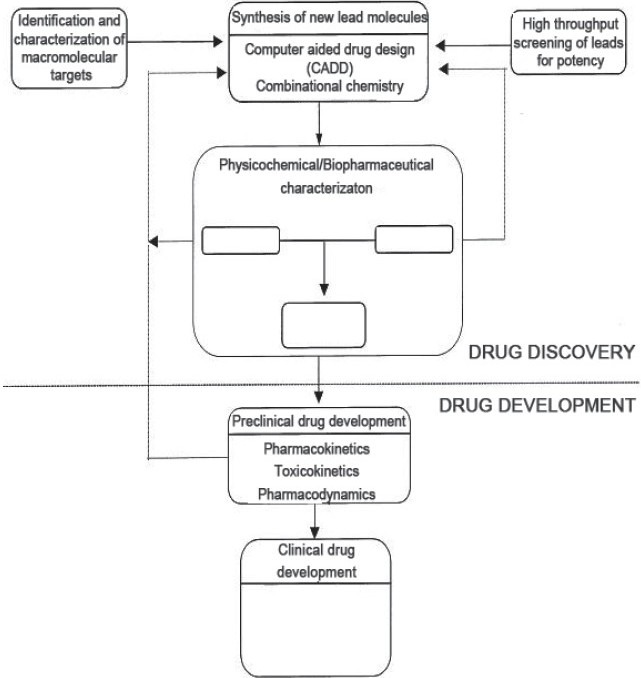

The drug research can be divided functionally into two stages: discovery/design and development [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Different stages of discovery/design and development

DRUG DISCOVERY/DESIGN

Initially, in the discovery stage, the aim of bioanalysis could be merely to provide reasonable values of either concentrations and/or exposure which would be used to form a scientific basis for lead series identification and/or discrimination amongst several lead candidates. Therefore, the aim of the analyst at this stage should be to develop a simple, rapid assay with significant throughput to act as a great screening tool for reporting some predefined parameters of several lead contenders across all the various chemical scaffolds.

The initial method of analysis developed during the discovery phase of the molecule, with some modifications, may sometimes serve as a method of choice to begin with as the NCE enters the preclinical development stage. Since the complexity of development generally tends to increase as the lead candidate enters the toxicological and clinical phase of testing, it naturally calls for improved methods of analytical quantization, improvement in selectivity and specificity, and employment of sound and rugged validation tools to enable estimation of PK parameters that would also aid in the decision-making of the drug molecule's advancement in the clinic in addition to safety and tolerability data gathered at all phases of development. Additionally, it becomes necessary to quantify active metabolite(s) in both animals and humans.[40]

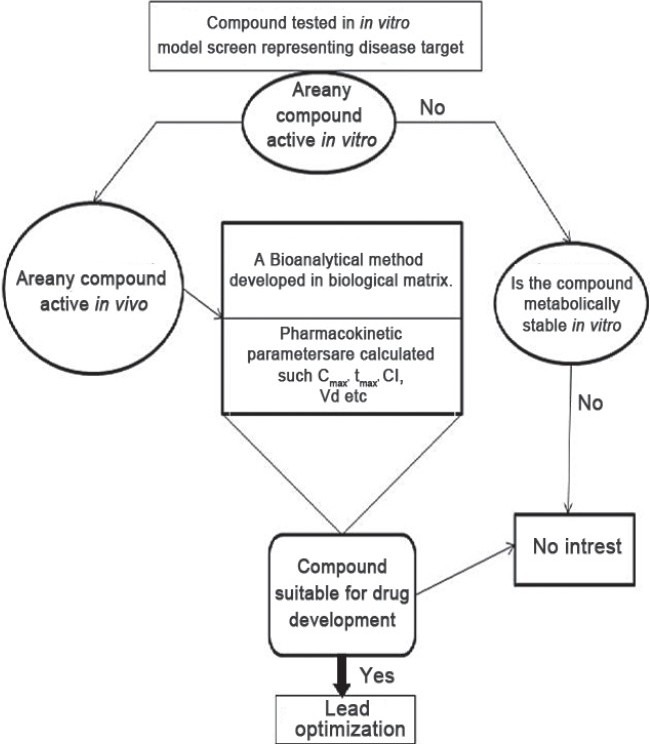

Drug discovery/design consists of identification and characterization of new targets (enzymes or receptors), synthesis of new lead molecules, screening of new lead molecules for in vitro and/or in vivo biological activities, and physicochemical characterization of leads.[41] For discovery, the priority is to examine a large number of compounds and determine which pharmacologically active compounds are most suitable for drug development. In practice, when a compound is obtained which has the required biological activity, a number of analogues or chemically similar compounds will be synthesized and tested to optimize the preferred characteristics of the compound (a process known as lead optimization). Using automated techniques, ultrahigh throughput can be obtained by the most advanced laboratories and tens of thousands of compounds can be screened in one day. In the secondary screening stage, physiochemical properties such as solubility, lipophilicity and stability are determined by using octanol–water partition coefficient and pKa. These measurements are useful in predicting protein binding, tissue distribution and absorption in gastrointestinal tract.[42] In parallel studies, information is learned on a drug molecule's absorption, distribution (including an estimate of protein binding), metabolism and elimination by sampling from dosed laboratory animals (called in vivo testing) and from working cells and/or tissues removed from a living organism (called in vitro testing since the cells are outside a living animal). For in vivo characterization of PK and bioavailability, it is necessary to administer the drug to selected animal species both intravenously and by the intended route of administration (usually oral). Whole blood samples are collected over a predetermined time course after dosing, and the drug is quantified in the harvested plasma by a suitable bioanalytical method. The use of in vitro drug metabolism approaches for the prediction of various in vivo PK characteristics is widely practiced in the pharmaceutical industry.[43–46] In particular, in vitro metabolic stability assessment using hepatic subcellular fractions to predict in vivo hepatic clearance is employed as part of the initial screening of candidates in a lead optimization program. This is because the liver is the main organ involved in the metabolism of xenobiotics, the process by which most drugs are cleared from the body. The correlation between in vivo hepatic clearance values and the intrinsic clearance values determined from liver microsomal incubation experiments is also well documented.[47–50] These important tests are collectively referred to as ADME characteristics (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism and Elimination).[26] Figure 2 shows an illustration of a possible scenario of bioanalysis in discovering drugs which are active in vitro and improving these by modification of the chemical structure optimized for in vivo activity.[51]

Figure 2.

Possible scenario of bioanalysis in discovering drugs

ADME/PK screening is usually taken to mean in vitro systems for studying absorption and metabolism. However, in vivo studies still provide the definitive assessment of overall drug disposition, and progress has been made in overcoming some of the constraints associated with this approach. Previously, drug metabolism studies were performed at a late stage of drug development process and very often not until the phase of clinical studies. Therefore, inadequate metabolism and PK parameters were the major reason of failure for NCEs.[52] Nowadays, introduction of in vitro approaches into drug metabolism enables the characterization of the metabolic properties of drug candidates at an earlier stage in the drug development process, at early preclinical studies performed during the drug discovery phase. Recently, the major reasons for high attrition rates have instead been identified to be lack of efficacy and safety, together accounting for approximately 60% of the failures. Cassette dosing is now an established method within the pharmaceutical industry as it provides a relatively quick way of ranking compounds according to their PK properties and requires the use of fewer animals.[53,54]

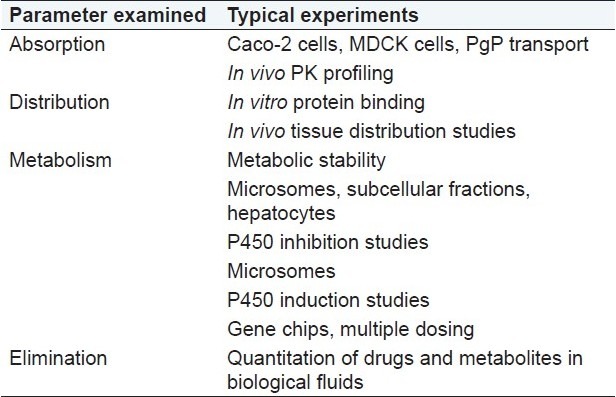

A list of experiments that are commonly performed to assess the ADME characteristics of potential lead compounds in drug discovery is given in Table 2.[26]

Table 2.

List of experiments to assess Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism and Elimination

DRUG DEVELOPMENT

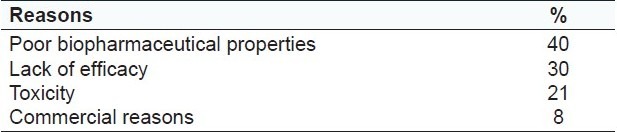

It focuses on evaluation of safety/toxicity and efficacy of new drug molecules. However, majority of the drug molecules fail in subsequent drug development program because the efficacy and safety are not governed by its PD characteristics alone. It also depends to a large degree on the biopharmaceutical (e.g., solubility, stability, permeability and first pass effect) and PK (clearance rate, biological half-life, extent of protein binding and volume of distribution) properties of the drug, since these properties control the rate and the extent to which the drug can reach its site of action, i.e., biophase[55]. Some data on reasons for withdrawal of candidate drugs from development have been published by the Center for Medicines Research[56] [Table 3].

Table 3.

Reasons for failure in drug development[57]

Preclinical stage

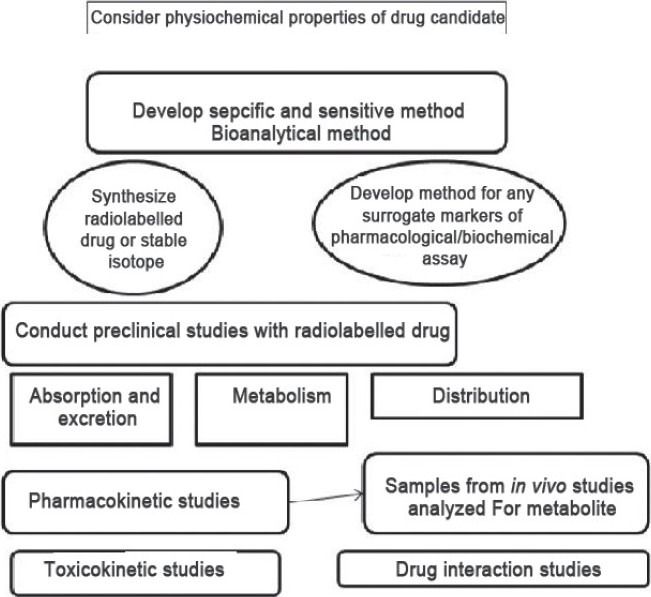

Once a chemical is identified as a new drug candidate, extensive preclinical analyses must be completed before the drug can be tested in humans.[57] The main goals of preclinical studies (also named nonclinical studies) are to determine a product's ultimate safety profile. Each class of product may undergo different types of preclinical research. For instance, drugs may undergo pharmacodynamics (PD), PK, ADME, and toxicity testing through animal testing. During preclinical investigation, validation should be formalized and mandated as per the required norm. The validation should address as many parameters as possible which are relevant, to obtain unambiguous analytical data [the list could include accuracy, precision, specificity, selectivity, linearity range, lower limit of quantification (LLQ), upper limit of quantification (ULQ), dilution effect, stability or extraction recovery]. Since the data gathered during this stage, especially PK and toxicokinetic properties of the NCE, would become part of the initial investigational new drug and clinical trial (IND/CTA) filings in several regions, the adherence to certain rigid validation parameters and protocols becomes of paramount importance. The developed assay at this stage may differ from the original assay of the discovery phase in that an internal standard addition may be used (in the event that an internal standard was not used before) to ensure reliability of the quantitation. It is a common practice in some pharmaceutical companies to incorporate a stable isotope labeled compound of the parent as an internal standard (IS) to provide extra comfort in the bioanalysis of NCEs at this stage.[58] It is especially valuable in lead optimization for studying the PK of multiple compounds administered simultaneously. Plasma levels of the drug are normally monitored to permit the calculation of PK parameters such as Cmax [maximum plasma concentration (e.g., ng/mL)] and AUC [area under the plasma concentration–time curve (e.g., ng h/mL)]. Distribution parameters describe the extent of drug distribution and are related to body volumes (e.g., mL or L), and time course parameters are related to time (t1/2, Tmax). These PK parameters are calculated from mathematical formulae, and specific computer programs are usually used to do this (e.g., WinNonlin).[59–63] The parameters may be estimated by compartmental or non-compartmental approaches (or model-dependent and model-independent, respectively). Figure 3 shows some possible steps of bioanalysis in the development stage of drugs. However, the determination of metabolite profiles is usually performed for a limited number of lead molecules in vivo and in vitro, and in these experiments the key issues are high specificity and sensitivity rather than speed.[64]

Figure 3.

Various steps of bioanalysis in the development stage of drugs

In the pharmaceutical industry, the term “toxicokinetics” is generally used to describe the PK performed at the dose levels used in the toxicological risk assessment of drugs. The aims of the toxicokinetic evaluation are

to define the relationship between systemic exposure to test compound and the administered dose,

to provide information on potential dose- and time-dependencies in the kinetics,

to determine the effect of age on the PK in animals, provide clearer delineation when there are sex-related differences, determine whether there are any changes in kinetics in pregnancy (during reproductive toxicology studies) and also provide greater detail on interspecies comparisons.

However, the overall aim in conducting toxicokinetics during safety studies is to extrapolate the risk assessment from the toxicity test species to humans.[51] Whilst preliminary PK and toxicokinetic data are obtained in drug development in preclinical species, the definitive kinetics is obtained in drug development by conducting single dose experiments in preclinical species and in humans. These data are essential in defining the dosage regimen in man and ensuring that the therapeutic benefit is maximized.[65–70]

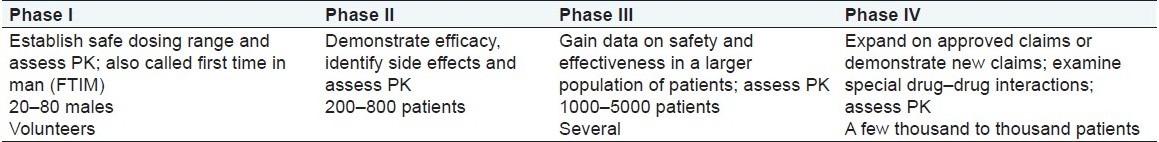

Clinical stage

Clinical trials are used to judge the safety and efficacy of new drug therapies in humans. Drug development comprises of four clinical phases: Phase I, II, III and IV [Table 4]. Each phase constitutes an important juncture, or decision point, in the drug's development cycle. A drug can be terminated at any phase for any valid reason. As the molecule advances into clinical development, the developed assay for human sample analyses (plasma, serum or urine matrix) needs to be more rugged, robust and be able to withstand the test of time during this the longest phase of clinical development.[71–79]

Table 4.

Objectives of the four phases in clinical drug development and typical numbers of volunteers or patients involved

The requirements and adherence to specificity, selectivity and stability will become very important. Since it is likely that patients will be concomitantly ingesting other medications, the assay has to be flexible enough to accommodate minor alterations in chromatographic conditions to circumvent the interfering peaks, if necessary.

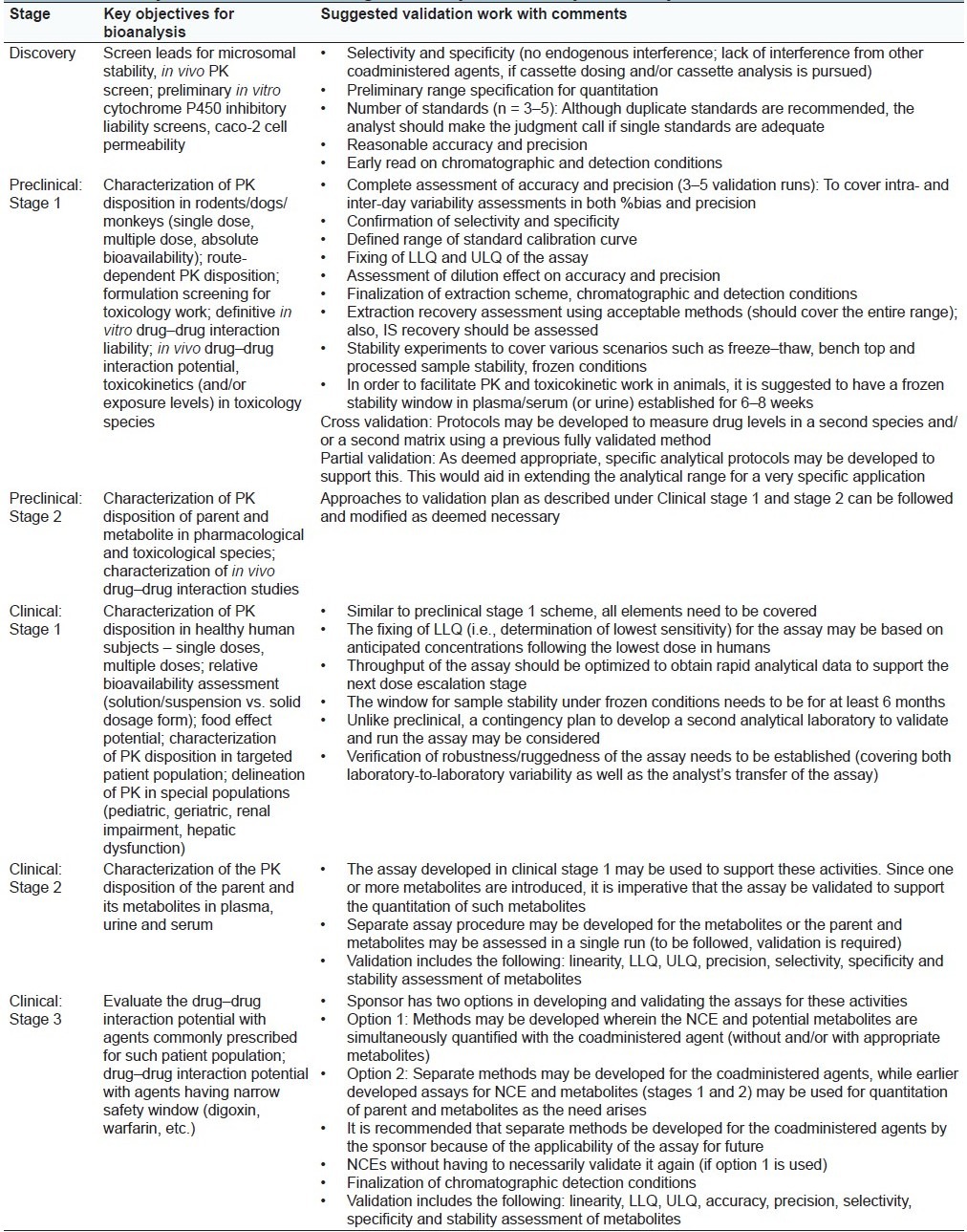

Table 5 provides a framework of the various stages of bioanalytical assay development (discovery, preclinical and clinical), key objectives that assay would support and some suggested validation workup that may be required to achieve the end goals. Based on the presentation [Table 1], it is apparent that assays developed in the early discovery stage may find utility during the course of an NCE's progress in development.

Table 5.

Bioanalytical framework in drug discovery and development: Key considerations

CONCLUSION

The need for sound bioanalytical methods is well understood and appreciated in the discovery phase and during the preclinical and clinical stages of drug development. Therefore, it is generally accepted that sample preparation and method validation are required to demonstrate the performance of the method and the reliability of the analytical results. The acceptance criteria should be clearly established in a validation plan, prior to the initiation of the validation study. The developed assay should be sufficiently rugged that it provides opportunities for minor modifications and/or ease of adoptability to suit other bioanalytical needs such as applicability to a drug–drug interaction study, toxicokinetic study as well as for characterization of the plasma levels of the metabolites. For bioanalytical liquid chromatographic methods, sample preparation techniques, the essential validation parameters with their guidelines and suggested validation work in drug discovery and development phase have been discussed here.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hop CE, Prakash C. Application in drug discovery and development. In: Chowdhury SK, editor. Chapter 6: Metabolite identification by LC-MS. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2005. p. 123. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Humphrey MJ. Application of metabolism and pharmacokinetic studies to the drug discovery process. Drug Metab Rev. 1996;28:473–89. doi: 10.3109/03602539608994012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin JH, Lu AY. Role of pharmacokinetics and metabolism in drug discovery and development. Pharmacol Rev. 1997;49:403–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Arcy PF, Harron DW, editors. Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Harmonisation. Yokohama: 1995. ICH: Note for guidance on toxicokinetics: The assessment of systemic exposure in toxicity studies; pp. 721–34. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell B, Bode G. Proceedings of the DIA Workshop “Toxicokinetics: The Way Forward. Drug Inf J. 1994;28:143–295. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kantharaj E, Tuytelaars A, Proost PE, Ongel Z, van AH, Gillissen AH. Simultaneous measurement of drug metabolic stability and identification of metabolites using ion-trap mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2003;17:2661. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bu HZ, Magis L, Knuth K, Teitelbaum P. High-throughput cytochrome P450 (CYP) inhibition screening via a cassette probedosing strategy. VI. Simultaneous evaluation of inhibition potential of drugs on human hepatic isozymes CYP2A6, 3A4, 2C9, 2D6 and 2E1. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2001;15:741. doi: 10.1002/rcm.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai Z, Sinhababu AK, Harrelson S. Simultaneous quantitiative cassette analysis of drugs and detection of their metabolites by high performance liquid chromatogramphy/ion trap mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2000;14:1637. doi: 10.1002/1097-0231(20000930)14:18<1637::AID-RCM73>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott RJ, Palmer J, Lewis IA, Pleasance S. Determination of a ‘GW cocktail’ of cytochrome P450 probe substrates and their metabolites in plasma and urine using automated solid phase extraction and fast gradient liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 1999;13:2305. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0231(19991215)13:23<2305::AID-RCM790>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gautam N, Singh RP, Pratap R, Singh SK. Liquid chromatographic-tandem mass spectrometry assay for quantitation of a novel antidiabetic S002-853 in rat plasma and its application to pharmacokinetic study. Biomed Chromatogr. 2010;24:692–8. doi: 10.1002/bmc.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satonin DK, McCulloch JD, Kuo F, Knadler MP. Development and validation of a liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometric method for the determination of major metabolites of duloxetine in human plasma. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2007;852:582–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeng J, Onthank D, Crane P, Unger S, Zheng N, Pasas-Farmer S, et al. Simultaneous determination of a selective adenosine 2A agonist, BMS-068645, and its acid metabolite in human plasma by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry—evaluation of the esterase inhibitor, diisopropyl fluorophosphates, in the stabilization of a labile ester containing drug. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2007;852:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He F, Bi HC, Xie ZY, Zuo Z, Li JK, Li X, et al. Rapid determination of six metabolites from multiple cytochrome P450 probe substrates in human liver microsome by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry: application to high throughput inhibition screening of terpenoids. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2007;21:635–43. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chawla S, Ghosh S, Sihorkar V, Nellore R, Kumar TR, Srinivas NR. High performance liquid chromatography method development and validation for simultaneous determination of five model compounds—antipyrine, metoprolol, ketoprofen, furesemide and phenol red, as a tool for the standardization of rat insitu intestinal permeability studies using timed wavelength detection. Biomed Chromatogr. 2006;20:349–57. doi: 10.1002/bmc.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mercolini L, Mandrioli R, Finizio G, Boncompagni G, Raggi MA. Simultaneous HPLC determination of 14 tricyclic antidepressants and metabolites in human plasma. J Sep Sci. 2010;33:23–30. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200900493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh RP, Sabarinath S, Singh SK, Gupta RC. A sensitive and selective liquid chromatographic tandem mass spectrometric assay for simultaneous quantification of novel trioxane antimalarials in different biomatrices using sample-pooling approach for high throughput pharmacokinetic studies. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2008;864:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Venkatesh G, Majid MI, Ramanathan S, Mansor SM, Nair NK, Croft SL, et al. Optimization and validation of RP-HPLC-UV method with solid-phase extraction for determination of buparvaquone in human and rabbit plasma: application to pharmacokinetic study. Biomed Chromatogr. 2008;22:535–41. doi: 10.1002/bmc.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Navin G, Amin EL, Eugene G, Guenther H. Simultaneous Determination of Dexamethasone, Dexamethasone 21-Acetate, and Paclitaxel in a Simulated Biological Matrix by RP-HPLC: Assay Development and Validation. J Liq Chromatogr Relat Technol. 2008;31:1478–91. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Podilsky G, Gryllaki MB, Testa B, Pannatier A. Development and Validation of an HPLC Method for the Simultaneous Monitoring of Bromazepam and Omeprazole. J Liq Chromatogr Relat Technol. 2008;31:878–90. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basha SJ, Naveed SA, Tiwari NK, Shashikumar D, Muzeeb S, Kumar TR, et al. Concurrent determination of ezetimibe and its phase- I and II metabolites by HPLC with UV detection: Quantitative application to various in vitro metabolic stability studies and for qualitative estimation in bile. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2007;853:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Link B, Haschke M, Wenk M, Krahenbuhl S. Determination of midazolam and its hydroxyl metabolites in human plasma and oral fluid by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization ion trap tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2007;21:1531. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oostendrop RL, Beijnen JH, Schellens JH, Tellingen OV. Determination of imatinib mesylate and its main metabolite (CGP74588) in human plasma and murine specimens by ionpairing reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Biomed Chromatogr. 2007;21:747. doi: 10.1002/bmc.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keil K, Hochreitter J, DiFrancesco R, Zingman BS, Reichman RC, Fischl MA, et al. Integration of atazanavir into an existing liquid chromatography UV method for protease inhibitors: validation and application. Ther Drug Monit. 2007;29:103. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3180318ef3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith DA, Beaumont K, Cussans NJ, Humphrey MJ, Jezequel SG, Rance DJ, et al. Bioanalytical data in decision making: Discovery and development. Xenobiotica. 1992;22:1195–205. doi: 10.3109/00498259209051873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.James CA, Breda M, Baratte S, Casati M, Grassi S, Pellegatta B, et al. Analysis of Drug and Metabolites in tissues and other solid matrices. Chromatogr Suppl. 2004;59:149–56. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wells DA. High throughput bioanalytical sample preparation methods and automation strategies. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2002. Fundamental strategies for bioanalytical sample preparation; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahuja S, Rasmussen H. HPLC method development of pharmaceuticals. Chapter 11: HPLC method development for drug discovery LC-MS assays in rapid PK applications. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu X. Book Using mass spectrometry for drug metabolism studies. In: Korfmacher W, editor. Chapter 7: Fast Metabolite Screening in a Discovery Setting. 2nd ed. CRC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Churchwell MI, Twaddle NC, Meeker LR, Doerge DR. Improving LC-MS sensitivity through increases in chromatographic performance: Comparison of UPLC-ES/MS/MS to HPLC-ES/MS/MS. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2005;825:134–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guidance for Industry: Bioanalytical Method Validation. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, FDA, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; 2001. Food and Drug Administration. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hartmann C, Smeyers-Verbeke J, Massart DL, McDowall RD. Validation of bioanalytical chromatographic methods. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1998;17:193–218. doi: 10.1016/s0731-7085(97)00198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shah VP, Midha KK, Dighe S, McGilveray IJ, Skelly JP, Yacobi A, et al. Analytical methods validation: bioavailability, bioequivalence and pharmacokinetic studies. Conference report. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1991;16:249–55. doi: 10.1007/BF03189968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shah VP, Midha KK, Findlay JW, Hill HM, Hulse JD, McGilveray IJ, et al. Bioanalytical method validation--a revisit with a decade of progress. Pharm Res. 2000;17:1551–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1007669411738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosing H, Man WY, Doyle E, Bult A, Beijnen JH. Bioanalytical liquid chromatographic method validation. a review of current practices and procedures. J Liq Chromatogr Relat Technol. 2000;23:329–54. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dadgar D, Burnett PE. Issues in evaluation of bioanalytical method selectivity and drug stability. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1995;14:23–31. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(95)01634-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karnes HT, Shiu G, Shah VP. Validation of bioanalytical methods. Pharm Res. 1991;8:421–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1015882607690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krull IS, Swartz M. Analytical method development and validation for the academic researcher. Anal Lett. 1999;32:1067–80. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braggio S, Barnaby RJ, Grossi P, Cugola M. A strategy for validation of bioanalytical methods. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1996;14:375–88. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(95)01644-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peng GW, Chiou WL. Analysis of drugs and other toxic substances in biological samples for pharmacokinetic studies. J Chromatogr. 1990;531:3–50. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)82279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Srinivas NR. Applicability of bioanalysis of multiple analytes in drug discovery and development: review of select case studies including assay development considerations. Biomed Chromatogr. 2006;20:383–414. doi: 10.1002/bmc.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Panchagnula R, Thomas NS. Biopharmaceutics and pharmacokinetics in drug research. Int J Pharm. 2000;201:131–50. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(00)00344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watari N, Sugiyama Y, Kaneniwa N, Hiura M. Prediction of hepatic first-pass metabolism and plasma levels following intravenous and oral administration of barbiturates in the rabbit based on quantitative structure-pharmacokinetic relationships. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1988;16:279–301. doi: 10.1007/BF01062138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng KC, Li C, Liu T, Wang G, Hsieh Y, Yunsheng P, et al. Use of Pre-Clinical In Vitro and In Vivo Pharmacokinetics for the Selection of a Potent Hepatitis C Virus Protease Inhibitor, Boceprevir, for Clinical Development. Lett Drug Des Discov. 2009;6:312–8. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu B, Chang J, Gordon WP, Isbell J, Zhou Y, Tuntland T. Snapshot PK: A rapid in vivo preclinical screening approach. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:360–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rostami-Hodjegan A, Tucker GT. Simulation and prediction of in vivo drug metabolism in human populations from in vitro data. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:140–8. doi: 10.1038/nrd2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wienkers LC, Heath TG. Predicting in vivo drug interactions from in vitro drug discovery data. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:825–33. doi: 10.1038/nrd1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Naritomi Y, Terashita S, Kimura S, Suzuki A, Kagayama A, Sugiyama Y. Prediction of Human Hepatic Clearance from in Vivo Animal Experiments and in Vitro Metabolic Studies with Liver Microsomes from Animals and Humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2001;29:1316–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Obach RS. Prediction of human clearance of twenty-nine drugs from hepatic microsomal intrinsic clearance data: An examination of in vitro half-life approach and nonspecific binding to microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27:1350–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Houston JB. Utility of in vitro drug metabolism data in predicting in vivo metabolic clearance. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;47:1469–79. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90520-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clarke SE, Jeffrey P. Utility of metabolic stability screening: comparison of in vitro and in vivo clearance, Xenobiotica: 1366-5928. 2001;31(8):591–598. doi: 10.1080/00498250110057350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wells DA. High throughput bioanalytical sample preparation methods and automation strategies. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2002. Fundamental strategies for bioanalytical sample preparation; p. 4. 25. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Evans G. A handbook of bioanalysis and drug metabolism. New York LLC: CRC Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kola I, Landis J. Can the pharmaceutical industry reduce attrition rates? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:711–5. doi: 10.1038/nrd1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eddershaw PJ, Beresford AP, Bayliss MK. ADME/PK as part of a rational approach to drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2000;5:409–14. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(00)01540-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.White RE, Manitpisitkul P. Pharmacokinetic theory of cassette dosing in drug discovery Screening. Drug Metab Dispos. 2001;29:957–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Panchagnula R, Thomas NS. Biopharmaceutics and pharmacokinetics in drug research. Int J Pharm. 2000;201:131–50. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(00)00344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prentis RA, Lis Y, Walker SR. Pharmaceutical innovation by the seven UK-owned pharmaceutical companies (1964-1985) Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;25:387–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1988.tb03318.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Joseph TD. Encyclopedia of clinical pharmacy. London, Newyork: Taylor and Francis Group, Marcel Dekker; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wieling J. LC-MS-MS Experiences with Internal Standards. Chromatographia Supplement. 55. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu A, Lou H, Zhao L, Fan P. Validated LC/MS/MS assay for curcumin and tetrahydrocurcumin in rat plasma and application to pharmacokinetic study of phospholipid complex of curcumin. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2006:720–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2005.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lu T, Liang Y, Song J, Xie L, Wang GJ, Liu XD. Simultaneous determination of berberine and palmatine in rat plasma by HPLC–ESI-MS after oral administration of traditional Chinese medicinal preparation Huang-Lian-Jie-Du decoction and the pharmacokinetic application of the method. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2006;40:1218–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Singh SS, Sharma K, Barot D, Mohan PR, Lohray VB. Estimation of carboxylic acid metabolite of clopidogrel in Wistar rat plasma by HPLC and its application to a pharmacokinetic study. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2005;821:173–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu QF, Fang XL, Chen DF. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of ginsenoside Rb1 and Rg1 from Panax notoginseng in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;84:187–92. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00317-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hajdu R, Thompson R, Sundelof JG, Pelak BA, Bouffard FA, Dropinski JF, et al. Preliminary animal pharmacokinetics of the parenteral antifungal agent MK-0991 (L-743,872) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2339–44. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.11.2339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kostiainen R, Kotiaho T, Kuuranne T, Auriola S. Liquid chromatography/atmospheric pressure ionization-mass spectrometry in drug metabolism studies. J Mass Spectrom. 2003;38:357–72. doi: 10.1002/jms.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coowanitwong I, Keay SK, Natarajan K, Garimella TS, Mason CW, Grkovic D, et al. Toxicokinetic Study of Recombinant Human Heparin-Binding Epidermal Growth Factor-Like Growth Factor (rhHB-EGF) in Female Sprague Dawley Rats. Pharm Res. 2008;25:542–50. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9392-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brown AP, Carlson TC, Loi CM, Graziano MJ. Pharmacodynamic and toxicokinetic evaluation of the novel MEK inhibitor, PD0325901, in the rat following oral and intravenous administration. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;59:671–9. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0323-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baldrick P. Toxicokinetics in preclinical evaluation. Drug Discov Today. 2003;8:127–33. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(02)02568-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Welling PG, Iglesia FA. Drug toxicokinetics. New York: Marcel and Dekker; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Morgan DG, Kelvin AS, Kinter LB, Fish CJ, Kerns WD, Rhodes G. The Application of Toxicokinetic Data to Dosage Selection in Toxicology Studies. Toxicol Pathol. 1994;22:112–23. doi: 10.1177/019262339402200205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Quaile MP, Melich DH, Jordan HL, Nold JB, Chism JP, Polli JW. Toxicity and toxicokinetics of metformin in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010:340–7. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Higashi Y, Gao R, Fujii Y. Determination of Fluoxetine and Norfluoxetine in Human Serum and Urine by HPLC Using a Cholester Column with Fluorescence Detection. J Liq Chromatogr Relat Technol. 2009;32:1141–51. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kavvadias D, Scherer G, Urban M, Cheung F, Errington G, Shepperd J, et al. Simultaneous determination of four tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines (TSNA) in human urine. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2009;887:1185–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Bruijn P, Moghaddam-Helmantel IM, de Jonge MJ, Meyer T, Lam MH, Verweij J, et al. Validated bioanalytical method for the quantification of RGB-286638, a novel multi-targeted protein kinase inhibitor, in human plasma and urine by liquid chromatography/tandem triple-quadrupole mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Ana. 2009;50:977–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2009.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Glade Bender JL, Adamson PC, Reid JM, Xu L, Baruchel S, Shaked Y, et al. Phase I Trial and Pharmacokinetic Study of Bevacizumab in Pediatric Patients With Refractory Solid Tumors: A Children's Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:399–405. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Laurie SA, Gauthier I, Arnold A, Shepherd FA, Ellis PM, Chen E, et al. Phase I and Pharmacokinetic Study of Daily Oral AZD2171, an Inhibitor of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Tyrosine Kinases, in Combination With Carboplatin and Paclitaxel in Patients With Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: The National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1871–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Masuda Y, Kanayama N, Manita S, Ohmori S, Ooie T. Development and validation of bioanalytical methods for Imidafenacin (KRP-197/ONO-8025) and its metabolites in human plasma by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2007;53:70–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yamane N, Tozuka Z, Sugiyama Y, Tanimoto T, Yamazaki A, Kumagai Y. Microdose clinical trial: Quantitative determination of fexofenadine in human plasma using liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2007;858:118–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oswald S, Scheuch E, Cascorbi I, Siegmund W. LC–MS/MS method to quantify the novel cholesterol lowering drug ezetimibe in human serum, urine and feces in healthy subjects genotyped for SLCO1B1. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2006;830:143–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]