Abstract

We compared the severity of white matter T2-hyperintensities (WMH) in the frontal lobe and occipital lobe using a visual MRI score in 102 patients with lobar intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) diagnosed with possible or probable cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), 99 patients with hypertension-related deep ICH, and 159 normal elderly subjects from a population-based cohort. The frontal-occipital (FO) gradient was used to describe the difference in the severity of WMH between the frontal lobe and occipital lobe. A higher proportion of subjects with obvious occipital dominant WMH (FO gradient ≤−2) was found among patients with lobar ICH than among healthy elderly subjects (FO gradient ≤−2: 13.7 vs. 5.7%, p = 0.03). Subjects with obvious occipital dominant WMH were more likely to have more WMH (p = 0.0006) and a significantly higher prevalence of the apolipoprotein E ε4 allele (45.8% vs. 19.4%, p = 0.04) than those who had obvious frontal dominant WMH. This finding is consistent with the relative predilection of CAA for posterior brain regions, and suggests that white matter lesions may preferentially occur in areas of greatest vascular pathology.

Keywords: Intercerebral hemorrhage, White matter hyperintensity, Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

Introduction

White matter lesions are widely detected on brain MRI scans of elderly people. As suggested by neuropathological studies, the frontal white matter develops later during youth and deteriorates earlier during aging than the posterior white matter [1, 2]. The frontal lobe dominance of white matter lesions with aging is supported by population-based MRI studies [3] as well as by studies using diffusion tensor imaging in normal elderly subjects [4]. However, elderly patients with posterior dominant white matter lesions are not rare in clinical experience.

Disease of the mall cerebral vessels is considered to play a central role in the pathogenesis of white matter lesions. The distribution of small vessel involvement varies among different pathological processes. Hypertensive arteriosclerosis can be detected in both cortical and subcortical areas without specific preference for any lobe, while in cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) the posterior regions (including the occipital cortex), are predominantly affected [5]. It is not clear whether the pattern of frontal lobe dominance of white matter lesions varies with different regional distributions of underlying microvascular pathological changes. Since the most accepted mechanisms attributed to the development of white matter lesions are ischemia and chronic leakage of fluid and macromolecules [6], the white matter lesions might be more severe in areas where more vessels are affected.

In a cohort comprising 182 patients with primary lobar intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) caused by CAA, periventricular white matter hyperintensities (WMH) were found to be greater around the occipital horn of the lateral ventricle than around the frontal horn, which supports the previous hypothesis [7]. However, when compared with patients with deep ICH caused by hypertension, no difference in the supratentorial distribution of WMH was detected using voxel-wise frequency analysis [8]. To better define the significance of these previous findings, we specifically compared the severity of WMH in the frontal lobe and occipital lobes within each subject, as this comparison has not been performed in most studies to date.

In this study, a semiquantitative visual MRI score was used to compare the severity of WMH in the frontal and occipital lobes in each subject. We then sought to determine whether the pattern of frontal or occipital dominant WMH differed among patients with CAA-related lobar ICH and hypertension-related deep ICH, and healthy elderly subjects.

Methods

Study population

Subjects in patients with ICH were drawn from an ongoing longitudinal cohort study as previously described [9]. All subjects were recruited from among consecutive patients age ≥55 years admitted to the Massachusetts General Hospital from January 2003 to December 2008 with lobar or deep ICH. Lobar ICH was defined as selective involvement of the cerebral cortex and underlying white matter. All subjects with lobar ICH (n = 102) had a diagnosis of probable or possible CAA as defined by the Boston criteria [10]. Deep ICH (n = 99) was defined as ICH involving the basal ganglia, thalamus or brainstem. This study was performed with the approval of the institutional review board of the Massachusetts General Hospital. All participating subjects provided written informed consent for participation in this study.

Healthy aging subjects were from the three-city study (3C group) which is a population-based cohort conducted in three cities in France (Bordeaux, Dijon, Montpellier). The detailed description of the study protocol, approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Kremlin-Bicêtre, has been previously reported [11]. Each participant signed an informed consent statement. Among the 4,931 non-instituted individuals recruited in Dijon, those who were aged between 65 and 80 years (n = 2,763) and enrolled between June 1999 and September 2000 were scheduled to have a cerebral MRI examination including T1, T2 and proton density weighted sequences. The data reported here were restricted to 160 participants randomly selected to have an additional scanning protocol including T1, T2, proton density and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences. Individuals with dementia (n = 1) or self-reported history of stroke (n = 0) at baseline were excluded, so that 159 subjects in this group were included in the final analysis.

Risk factors assessment

Subjects were considered to have a history of ischemic heart disease if a history of myocardial infarction, bypass cardiac surgery, or angioplasty was reported. Subjects were considered to have diabetes mellitus if they were taking antidiabetic drugs, or if fasting blood glucose was ≥7 mmol/l. Hypercholesterolemia was defined as total cholesterol ≥6.2 mmol/l or the use of lipid-lowering drugs. Subjects were considered to have hypertension if they had a high blood pressure (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg), or if they were taking antihypertensive drugs. Smoking status was categorized as never, former, and current. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotyping was performed using a procedure described elsewhere [9].

Image acquisition

All brain MRI scans were acquired using a 1.5-T magnet. FLAIR images were acquired in the axial plane (TR/TE 7,500/119 ms, slice thickness 7.2 mm, interslice gap 0 mm, 256 × 256) as previously described in 3C subjects [3]. Comparable sequence parameters were used in patients with ICH (TR/TE 10,000/140 ms, slice thickness 5 mm, interslice gap 1.0 mm, 256 × 256) [12].

Rating of white matter hyperintensities

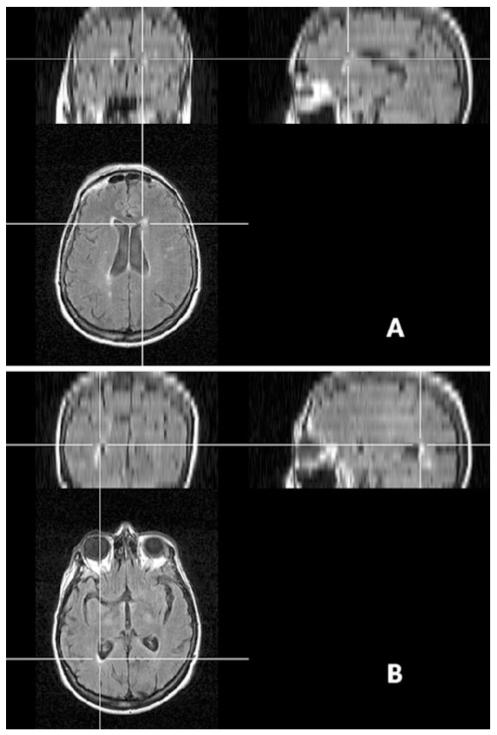

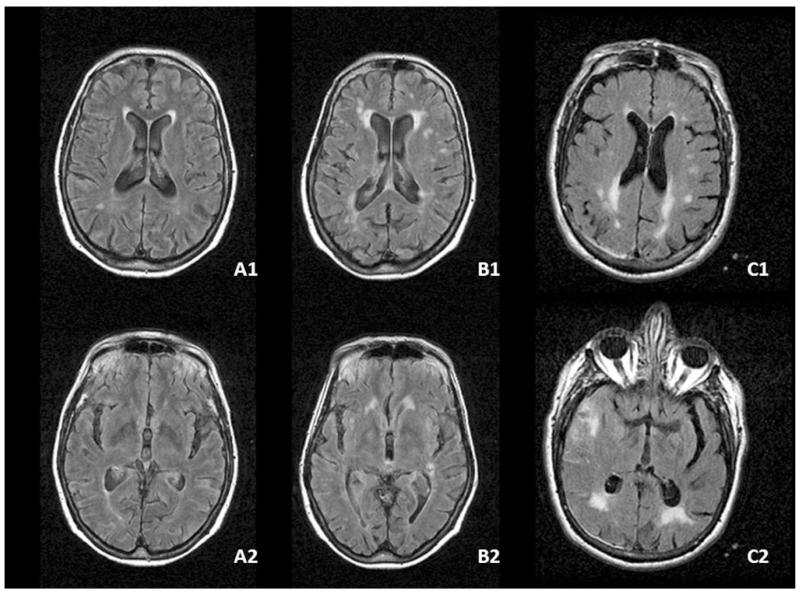

WMH were rated on axially oriented FLAIR images. Multiplanar reformatting was applied to help the orientation of WMH (Fig. 1). WMH in frontal the lobe were evaluated around the frontal horn of the lateral ventricle and WMH in the occipital lobe were evaluated around the occipital horn of the lateral ventricle. Visual scales were used to rate WMH surrounding the ventricles (≤5 mm from ventricle), within juxtacortical white matter (≤5 mm from the cortex) and within the deep white matter (defined as the region between juxtacortical and ventricular areas) separately. WMH in the frontal lobe and occipital lobes were evaluated separately. Periventricular WMH were graded as 0 (absent, 1 (caps or pencil-thin periventricular lining), 2 (smooth halo or thick lining). WMH in deep or in juxtacortical white matter were also graded as 0 (absent, 1 (punctate or nodular foci), 2 (confluent areas). The overall degree was then calculated for the frontal and occipital lobes by adding the scores for these three areas (range 0–6). Additionally, the frontal-occipital (FO) gradient (the WMH score in the frontal lobe minus that in the occipital lobe) was used to describe the difference in the severity of white matter lesions between the frontal lobe and the occipital lobes (ranging −6 to 6; >0 implies frontal dominance and <0 implies occipital dominance; Fig. 2). Obvious occipital dominant WMH was defined as an FO gradient of ≤−2 and obvious frontal dominant WMH was when the FO gradient ≥2. For the subjects with ICH, WMH were evaluated within the hemisphere without hematomas as previously described [12]. The global burden of WMH was evaluated using the scale of Fazekas (range 0–3). One experienced reader (Y.-C.Z) who was blinded to all clinical data analyzed all images. The intrarater agreement for the FO gradient was assessed on a random sample of 60 individuals (20 from each group) with an interval of 1 month between the first and second readings. The kappa statistic of the intrarater agreement was 0.79 indicating good reliability.

Fig. 1.

Orientation of the WMH using multiplanar reformatting. The location of the WMH can be oriented using multiplanar reformatting regardless of the head position during scanning. a WMH located around the frontal horn of the lateral ventricle. b WMH located around the occipital horn of the lateral ventricle

Fig. 2.

WMH severity scores in the frontal and occipital lobes and their gradients. A1 (case A) score 2 in the frontal lobe white matter (periventricular 2, deep 0, juxtacortical 0), smooth halo limited to within 5 mm of the frontal horn of the lateral ventricle; A2 (case A) score 1 in the occipital lobe white matter (periventricular 1, deep 0, juxtacortical 0), pencil-thin periventricular lining around the occipital horn of the ventricle (A1–A2 FO gradient 1). B1 (case B) score 4 in the frontal lobe white matter (periventricular 2, deep 1, juxtacortical 1); B2 (case B) score 1 in the occipital lobe white matter (periventricular 1, deep 0, juxtacortical 0) (B1–B2 FO gradient 3). C1 (case C) score 2 in the frontal lobe white matter (periventricular 1, deep 1, juxtacortical 0); C2 (case C) score 5 in the occipital lobe white matter (periventricular 2, deep 2, juxtacortical = 1) (C1–C2 FO gradient −3)

Statistical analysis

The different clinical and demographic characteristics of the three groups were compared using the chi-squared and the Mantel-Haenszel tests adjusted for age and gender. To evaluate the risk of having obvious occipital dominant WMH, polytomous logistic regression models (reference group = FO gradient = [−1 to 1]) adjusted for age and gender were applied. To compare characteristic differences between subjects with obvious frontal dominant WMH and those with obvious occipital dominant WMH, the chi-squared test was used for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. SAS (release 9.1; SAS Statistical Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the three groups are shown in Table 1. Subjects with deep hemispheric ICH were significantly younger than those in the other two groups (p < 0.0001). There was a higher proportion of women in the 3C group (p = 0.01). Compared to the patients, the subjects in the 3C group were less likely to be a current smoker (p = 0.05), less likely to have diabetes (p = 0.001) and a history of cardiovascular disease (p = 0.0009), and had a lower WMH score (p < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with lobar and deep ICH, and healthy aging subjects from the 3C study

| Characteristic | Lobar ICH (n = 102) | Deep ICH (n = 99) | 3C group (n = 159) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 76.0 (9.0) | 66.4 (13.3) | 72.1 (3.7) | <0.0001 |

| Women, % (n) | 57.8 (59) | 43.4 (43) | 62.3 (99) | 0.01 |

| Hypertension, % (n) | 74.5 (76) | 83.8 (83) | 71.1 (113) | 0.06 |

| Diabetes, % (n) | 14.7 (15) | 25.3 (25) | 8.3 (13) | 0.001 |

| History of cardiovascular disease, % (n) | 10.8 (11) | 15.3 (15) | 2.5 (4) | 0.0009 |

| Current smoker, % (n) | 13.4 (11)d | 16.9 (14)e | 6.9 (11) | 0.05 |

| Cholesterol medication, % (n) | 38.6 (39) | 29.6 (29) | 36.5 (58) | 0.37 |

| Apolipoprotein ε4 allele carrier, % (n) | 42.0 (21)f | 28.9 (13)g | 26.9 (42)h | 0.13 |

| Fazekas score, median | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | <0.00 |

| FO gradient, % (n) | ||||

| −1 to 1 | 79.4 (81)a | 83.8 (83)b | 81.1 (129) | 0.10c |

| ≤−2 | 13.7 (14) | 7.1 (7) | 5.7 (9) | |

| ≥2 | 6.9 (7) | 9.1 (9) | 13.2 (21) |

ICH intracerebral hemorrhage, F-O gradient frontal-occipital gradient

p = 0.02, lobar ICH versus 3C group (Mantel-Haenszel analysis adjusted for age and gender)

p = 0.86, deep ICH versus 3C group (Mantel-Haenszel analysis adjusted for age and gender)

Significant differences across three groups (chi-squared analysis)

Data missing (n = 20)

Data missing (n = 16)

Data missing (n = 52)

Data missing (n = 54)

Data missing (n = 3)

The FO gradient distributions in the patients with lobar and deep ICH, and the 3C subjects are shown in Fig. 1. Approximately 40% of the subjects had a score of 0 in all three groups (39.2% in the lobar ICH group, 37.4% in the deep ICH group and 40.9% in the 3C group). An FO gradient >0 was more common than a gradient of <0 in all groups. The proportions of subjects with an FO gradient of ≤−1 (which suggests more WMH in the occipital lobe) were 29.4% in the lobar ICH group, 19.2% in the deep ICH group and 16.4% in the 3C group, whereas the proportions with an FO gradient of ≥1 were 31.4%, 43.4% and 42.8%, respectively.

We further compared the subjects with a gradient of ≥2 or ≤−2 which results in an obvious visual difference in WMH distribution (Fig. 2). A significantly higher proportion of subjects with obvious occipital dominant WMH (FO gradient ≤−2) and a lower proportion of those with obvious frontal dominant WMH (FO gradient ≥2) were found in the lobar ICH group compared to the 3C group (see Table 1). In contrast, significant differences were not detected between the lobar ICH and deep ICH groups, nor between the deep ICH and 3C groups (Table 1).

After adjustment for age and gender, patients with lobar ICH had twice the risk of having obvious occipital dominant WMH than subjects in the 3C group (adjusted OR 2.6, 95% CI 1.1–6.5), whereas patients with deep ICH did not have a higher risk of occipital dominant WMH (adjusted OR 1.3, 95% CI 0.5–3.8). No significant group differences were found in obvious frontal dominant WMH across the three groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Obvious frontal dominant WMH and occipital dominant WMH in patients with lobar or deep ICH, and healthy aging subjects from the 3C study

| OR (95% CI)a |

||

|---|---|---|

| FO gradient ≤−2 | FO gradient ≥2 | |

| Lobar ICH vs. 3C | 2.6 (1.1–6.5) | 0.5 (0.2–1.4) |

| Deep ICH vs. 3C | 1.3 (0.5–3.8) | 0.7 (0.3–1.8) |

| Lobar ICH vs. deep ICH | 2.0 (0.7–5.6) | 1.1 (0.3–3.5) |

ICH intracerebral hemorrhage

OR odds ratio, computed from polytomous logistic regression models (reference group = FO gradient = [−1 to 1]) adjusted for age and gender

Finally, we compared the characteristics between subjects with obvious occipital dominant WMH and those with obvious frontal dominant WMH among the whole population. There were in total 30 subjects with obvious occipital dominant WMH (14 with lobar ICH and 7 with deep ICH, and 9 healthy 3C subjects) and 37 with obvious frontal dominant WMH (7 with lobar ICH and 9 with deep ICH, and 21 healthy 3C subjects). Those with obvious frontal dominant WMH were more likely to be women (81.1 vs. 53.3%, p = 0.01). Those with obvious occipital dominant WMH were more likely to have a higher Fazekas score (2 vs. 1, p = 0.0006). Among the 56 subjects with available APOE data, a significantly higher prevalence of the ε4 allele (45.8 vs. 19.4%, p = 0.04) was detected in those with occipital dominant WMH (Table 3). Similar trends were found in the individual groups (prevalence of the ε4 allele in occipital dominant WMH patients versus that in frontal dominant patients: lobar group, 55.6% (5/9) versus 0% (0/6); deep group, 33.3% (2/6) versus 28.2% (1/5); 3C group, 44.4% (4/9) versus 26.4% (5/21)). These differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.08, 1.0 and 0.39, respectively), although this might have been related to the small number of subjects in each group.

Table 3.

Characteristics of subjects with obvious frontal dominant WMH and occipital dominant WMH

| Characteristic | Occipital dominant (FO gradient ≤−2) (n = 30) |

Frontal dominant (FO gradient ≥2) (n = 37) |

p valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 73.0 (7.5) | 69.9 (10.9) | 0.19 |

| Women, % (n) | 53.3 (16) | 81.1 (30) | 0.01 |

| Hypertension, % (n) | 66.7 (20) | 83.8 (31) | 0.10 |

| Diabetes, % (n) | 23.3 (7) | 8.1 (3) | 0.08 |

| History of cardiovascular disease, % (n) | 13.8 (4) | 5.4 (2) | 0.24 |

| Current smoker, % (n) | 14.3 (4)b | 11.1 (4)c | 0.70 |

| Cholesterol medication, % (n) | 23.3 (7) | 43.2 (16) | 0.09 |

| Apolipoprotein ε4 allele carrier, % (n) | 45.8 (11)d | 19.4 (6)e | 0.04 |

| Fazekas score, median | 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.0006 |

F-O gradient frontal-occipital gradient

Based on chi-squared analysis for qualitative variables or analysis of variance for continuous variables

Data missing (n = 2)

Data missing (n = 1)

Data missing (n = 6)

Data missing (n = 6)

Discussion

Using a visual semiquantitative MRI score, we compared the severity of WMH in the frontal lobe and occipital lobes in patients with deep and lobar ICH and in healthy elderly subjects. All patients with lobar ICH had possible or probable CAA. WMH were found to be equally distributed or have a frontal dominant distribution in more than half of the patients. Obvious occipital dominant distribution, however, was two times more prevalent in the patients with lobar ICH than in those with deep ICH or in the normal elderly subjects. Furthermore, these individuals were significantly more likely to harbor the APOE ε4 allele. An occipital dominant WMH was detected in one-third of patients with CAA-related lobar ICH while only one-sixth of the subjects from on the 3C group were found to have more WMH in the occipital lobe. The proportion of patients with occipital dominant WMH in the deep ICH group was slightly higher than that among the healthy elderly but lower than that in the lobar ICH group, although neither of the group differences was significant.

There is evidence to suggest that the white matter lesions in CAA are possibly caused by impairment of blood flow [13]. The heavy involvement of the occipital lobe in CAA vessel pathology may predispose this region to develop white matter lesions [7, 14-16]. A higher prevalence of the APOE ε4 allele was found in subjects with obvious occipital predominant WMH (FO gradient ≤−2). Moreover, 44.4% of the normal elderly subjects who showed obvious posterior dominant WMH also had at least one APOE ε4 allele. This proportion is comparable to that of the patients with CAA, whereas among the whole sample of the 3C study, the prevalence of APOE ε4 allele carriers was only 21.6% [17]. From these data, one could hypothesize that the obvious occipital dominant WMH in healthy elderly individuals might be associated with a higher risk of being an APOE ε4 allele carrier. Whether such individuals have subclinical CAA needs further investigation.

The occipital dominant WMH pattern has been previously investigated in patients with CAA or Alzheimer’s disease and normal aging subjects, with conflicting findings [7, 8, 13, 18]. Both voxel-based analyses and region of interest analyses have been reported. For example, Holland et al. [13] found no differences in spatial distribution of WMH among patients with CAA or Alzheimer’s disease and normal aging subjects using a voxel-based WMH frequency map. However, if group differences are relatively small but consistent across different regions of interest, voxel-based analyses may lack sufficient power to distinguish between groups. Furthermore, if different patterns of WMH distribution exist simultaneously within groups, averaging of all voxels will tend to minimize these differences. Our analysis may have had greater power to detect group differences compared to voxel-based analyses because of its region of interest based approach and larger sample size.

Other scales have previously been applied to compare the severity of WMH within subjects [8, 19]. However, in contrast to our evaluation (which was restricted to the WMH in the frontal lobe and occipital lobe), previous studies have compared anterior and posterior WMH in the slice through the centrum semiovale which results in evaluation of WMH mainly in the frontal lobe and parietal lobes [19].

Several limitations should be mentioned. We chose not to use a quantitative volumetric measurement of WMH, which could be considered a limitation. However, the motivation for this study was to describe visual differences in WMH distribution in a pragmatic manner for clinical practice, rather than to precisely compare WMH volumes. Although less quantitative, this approach may be able to better assess gradients of WMH burden across the whole lobe compared to strict volumetric, voxel-based analyses. We are unable to exclude subclinical CAA in the subset of 3C subjects or the combination of hypertensive vasculopathy and CAA in the same patient, which may become possible in future studies as molecular amyloid imaging becomes more widespread. We used a population-based cohort of elderly subjects as a control group. Although this cohort was similar in its demographic characteristics to the ICH subjects, the fact that this population geographically and ethnically differed from the ICH group may represent a limitation. Finally, ApoE4 genotyping was available in only a subgroup of patients with ICH which could have been a cause of bias in our results.

We found a higher prevalence of occipital dominant WMH in subjects with CAA-related lobar ICH than in normal elderly people using a semiquantitative visual score. These results suggest that obvious occipital dominant WMH may be a clue to CAA and deserve more clinical attention. A study examining the relationship between cerebral amyloid deposition and WMH distribution may help to identify the potential mechanisms of occipital dominant white matter lesions. Studies in larger cohorts will be necessary to confirm our findings and to have greater power for examining risk factors for occipital dominant WMH.

Acknowledgments

Yi-Cheng Zhu is funded by the French Chinese Foundation for Science and Applications (FFCSA), the China Scholarship Council (CSC), and the Association de Recherche en Neurologie Vasculaire (ARNEVA). Carole Dufouil has received consulting fees from EISAI. Christophe Tzourio has received investigator initiated research funding from the French National Research Agency (ANR) and has received fees from Sanofi-Synthelabo for participation on a data safety monitoring board and from Merck-Sharp & Dohm for participation on a scientific committee. Hugues Chabriat has already received fees from Eisai, Lundbeck, Servier and Johnson and Johnson companies for participating on data safety and scientific committees in studies unrelated to the present study.

Footnotes

Present Address: E. E. Smith, Calgary Stroke Program, Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

Conflicts of interest The authors report no conflicts of interest in the present study.

Contributor Information

Yi-Cheng Zhu, Department of Neurology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing, China; Department of Neurology CHU Lariboisière, Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris, INSERM U740, Paris, France; Unit 708 Neuroepidemiology, INSERM, Paris, France.

Hugues Chabriat, Department of Neurology CHU Lariboisière, Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris, INSERM U740, Paris, France.

Ophélia Godin, Unit 708 Neuroepidemiology, INSERM, Paris, France; UPMC Univ Paris 6, Paris, France.

Carole Dufouil, Unit 708 Neuroepidemiology, INSERM, Paris, France; UPMC Univ Paris 6, Paris, France.

Jonathan Rosand, Center for Human Genetic Research, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Steven M. Greenberg, Department of Neurology, Hemorrhagic Stroke Research Program, Massachusetts General Hospital Stroke Research Center, Harvard Medical School, 175 Cambridge Street, Suite 300, Boston, MA 02114, USA

Eric E. Smith, Department of Neurology, Hemorrhagic Stroke Research Program, Massachusetts General Hospital Stroke Research Center, Harvard Medical School, 175 Cambridge Street, Suite 300, Boston, MA 02114, USA

Christophe Tzourio, Unit 708 Neuroepidemiology, INSERM, Paris, France; UPMC Univ Paris 6, Paris, France.

Anand Viswanathan, Department of Neurology, Hemorrhagic Stroke Research Program, Massachusetts General Hospital Stroke Research Center, Harvard Medical School, 175 Cambridge Street, Suite 300, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

References

- 1.Bartzokis G, Beckson M, Lu PH, Nuechterlein KH, Edwards N, Mintz J. Age-related changes in frontal and temporal lobe volumes in men: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:461–465. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartzokis G. Age-related myelin breakdown: a developmental model of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:5–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Leeuw FE, De Groot JC, Achten E, Oudkerk M, Ramos LM, Heijboer R, Hofman A, Jolles J, van Gijn J, Breteler MM. Prevalence of cerebral white matter lesions in elderly people: a population based magnetic resonance imaging study. The Rotterdam scan study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70:9–14. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfefferbaum A, Adalsteinsson E, Sullivan EV. Frontal circuitry degradation marks healthy adult aging: evidence from diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage. 2005;26:891–899. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vinters HV, Gilbert JJ. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: incidence and complications in the aging brain. II. The distribution of amyloid vascular changes. Stroke. 1983;14:924–928. doi: 10.1161/01.str.14.6.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim KW, MacFall JR, Payne ME. Classification of white matter lesions on magnetic resonance imaging in elderly persons. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith EE, Gurol ME, Eng JA, Engel CR, Nguyen TN, Rosand J, Greenberg SM. White matter lesions, cognition, and recurrent hemorrhage in lobar intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2004;63:1606–1612. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000142966.22886.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith EE, Nandigam KR, Chen YW, Jeng J, Salat D, Halpin A, Frosch M, Wendell L, Fazen L, Rosand J, Viswanathan A, Greenberg SM. MRI markers of small vessel disease in lobar and deep hemispheric intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2010;41:1933–1938. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.579078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Donnell HC, Rosand J, Knudsen KA, Furie KL, Segal AZ, Chiu RI, Ikeda D, Greenberg SM. Apolipoprotein E genotype and the risk of recurrent lobar intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:240–245. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001273420403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knudsen KA, Rosand J, Karluk D, Greenberg SM. Clinical diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: validation of the Boston criteria. Neurology. 2001;56:537–539. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alperovitch A. Vascular factors and risk of dementia: Design of the three-city study and baseline characteristics of the study population. Neuroepidemiology. 2003;22:316–325. doi: 10.1159/000072920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viswanathan A, Patel P, Rahman R, Nandigam RN, Kinnecom C, Bracoud L, Rosand J, Chabriat H, Greenberg SM, Smith EE. Tissue microstructural changes are independently associated with cognitive impairment in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Stroke. 2008;39:1988–1992. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.509091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holland CM, Smith EE, Csapo I, Gurol ME, Brylka DA, Killiany RJ, Blacker D, Albert MS, Guttmann CR, Greenberg SM. Spatial distribution of white-matter hyperintensities in Alzheimer disease, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, and healthy aging. Stroke. 2008;39:1127–1133. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.497438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith EE, Vijayappa M, Lima F, Delgado P, Wendell L, Rosand J, Greenberg SM. Impaired visual evoked flow velocity response in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology. 2008;71:1424–1430. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327887.64299.a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson KA, Gregas M, Becker JA, Kinnecom C, Salat DH, Moran EK, Smith EE, Rosand J, Rentz DM, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Price JC, Dekosky ST, Fischman AJ, Greenberg SM. Imaging of amyloid burden and distribution in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol. 2007;62:229–234. doi: 10.1002/ana.21164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ly JV, Donnan GA, Villemagne VL, Zavala JA, Ma H, O’Keefe G, Gong SJ, Gunawan RM, Saunder T, Ackerman U, Tochon-Danguy H, Churilov L, Phan TG, Rowe CC. 11C-PIB binding is increased in patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related hemorrhage. Neurology. 2010;74:487–493. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cef7e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Godin O, Tzourio C, Rouaud O, Zhu Y, Maillard P, Pasquier F, Crivello F, Alperovitch A, Mazoyer B, Dufouil C. Joint effect of white matter lesions and hippocampal volumes on severity of cognitive decline: the 3C-Dijon MRI study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20:453–463. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshita M, Fletcher E, Harvey D. Extent and distribution of white matter hyperintensities in normal aging, MCI, and AD. Neurology. 2006;67:2192–2198. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000249119.95747.1f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Swieten JC, Hijdra A, Koudstaal PJ, van Gijn J. Grading white matter lesions on CT and MRI: a simple scale. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53:1080–1083. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.53.12.1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]