Abstract

Robust and simple strategies to directly functionalize graphene- and diamond-based nanostructures with proteins are of considerable interest for biologically driven manufacturing, biosensing and bioimaging. Here, we identify a new set of carbon binding peptides that vary in overall hydrophobicity and charge, and engineer two of these sequences (Car9 and Car15) within the framework of E. coli Thioredoxin 1 (TrxA). We develop purification schemes to recover the resulting TrxA derivatives in a soluble form and conduct a detailed analysis of the mechanisms that underpin the interaction of the fusion proteins with carbonaceous surfaces. Although equilibrium quartz crystal microbalance measurements show that TrxA∷Car9 and TrxA∷Car15 have similar affinity for sp2-hybridized graphitic carbon (Kd = 50 and 90 nM, respectively), only the latter protein is capable of dispersing carbon nanotubes. Further investigation by surface plasmon resonance and atomic force microscopy reveals that TrxA∷Car15 interacts with sp2-bonded carbon through a combination of hydrophobic and π-π interactions but that TrxA∷Car9 exhibits a cooperative mode of binding which relies on a combination of electrostatics and weaker π-stacking. Consequently, we find that TrxA∷Car9 binds equally well to sp2- and sp3-bonded (diamond-like) carbon particles, while TrxA∷Car15 is capable of discriminating between the two carbon allotropes. Our results emphasize the importance of understanding both bulk and molecular recognition events when exploiting the adhesive properties of solid-binding peptides and proteins in technological applications.

Keywords: solid binding peptide, hybrid materials, graphene, bionanotechnology, molecular biomimetics

INTRODUCTION

Solid-binding peptides (SBPs), designer proteins that incorporate them, and organisms that display them have emerged as powerful tools to synthesize and assemble functional materials through environmentally benign processes.1–5 It is now straightforward to rapidly isolate SBPs against virtually any material of interest by combinatorial technologies, exploit their adhesive properties for surface attachment, interface modification and part-to-part assembly, or harness their chemical reactivity or synthetic properties to promote or modulate the nucleation and growth of inorganic phases.1,2,4,6–8 While SBPs have great potential for enabling the fabrication of functional hybrid materials with programmed composition, crystallography and topology, the mechanisms through which they interact with solids are far from clear. A better understanding of these phenomena is key to the development of robust, biologically driven and controlled manufacturing processes.

Because of their superior mechanical, thermal, electrical and electronic properties, carbon-based nanomaterials have attracted considerable interest for applications ranging from composite materials to energy storage and next generation nanoelectronics.9–12 Carbon nanostructures, particularly sp2-bonded ones such as nanotubes and graphene, also hold promise in biosensing, drug delivery and bio-imaging applications.13–15 To interface with the biological world, naturally hydrophobic carbon nanomaterials must first be dispersed into aqueous solutions. This is typically done by chemical modification, which impacts functional properties, or the use of detergents or solubilizing agents that often denature proteins.16–18 Peptides that have been designed19,20 or selected21–25 for carbon binding provide an attractive alternative to chemical approaches to disperse, functionalize and manipulate carbon nanostructures. However, only proteins provide a versatile solubilizing framework whose structure and function can be engineered at will.1 Here, we report on the isolation of a new set of carbon binding peptides and perform a detailed investigation of how Thioredoxin A (TrxA) derivatives incorporating two of these peptides within their framework interact with carbonaceous substrates. The implications of our results for the mechanisms of carbon molecular structure recognition are discussed.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Carbon Binding Peptides and Proteins

The FliTrx cell surface display system (Invitrogen) was used to identify disulfide-constrained, carbon binding dodecapeptides (Car) using a previously described protocol26 and 12 mm siliconized glass discs (Hampton Research) coated with a carbon film (≈ 25 nm) by thermal evaporation in an Edwards Auto306 instrument.

Cell Binding

GI826 (F− lacIq ampC∷PtrpcI ΔfliC ΔmotB eda∷.Tn10) cells expressing FliTrx∷Car fusions on their flagella were grown overnight at 25°C in 5 mL of IMC medium (0.2% amicase, 0.5% glucose, 1 mM MgCl2, 100 µg/ml ampicillin) supplemented with 10 µg/mL carbenicillin. At A600 ≈ 1.5, aliquots corresponding to 109 cells (2 mL) were transferred to 125 mL shake flask containing 25 mL of IMC supplemented with carbenicillin and 100 µg/mL tryptophan to induce recombinant protein synthesis. After 6 h of growth, the A600 of samples was normalized to 1 (109 cells/mL) with IMC media and 5 mL of cells were contacted with carbon-coated glass discs in a 60 × 15mm polystyrene petri dish with shaking at ≈ 50 rpm. After 15 min, cells were removed by pipetting, and the discs were washed three times with 5mL of IMC media for 5 min. The discs were next transferred to the stage of an optical microscope and imaged with a 50x objective. The number of adhesive cells was determined by counting 5 randomly selected fields for two independent experiments.

DNA Manipulations and Protein Purification

Plasmids encoding E. coli Thioredoxin 1 (TrxA) variants incorporating carbon binding (Car) peptides within their active were constructed as described.27 BL21(DE3) cells harboring the resulting pTrx-CarX plasmids (where X denotes a particular carbon binding sequence) were grown overnight at 37°C in 25 mL Luria Broth (LB) supplemented with 34 µg/mL chloramphenicol. Seed cultures were used to induce 500 mL of supplemented LB medium and growth was allowed to proceed at 37°C to A600 ≈ 0.5. Flasks were transferred to a 25°C water bath for 10 min and protein synthesis was induced with 1mM isopropyl β-D thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). After 6 hours, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 7,000g for 5 min. TrxA∷Car9 was purified as previously described.27 TrxA∷Car15 was first recovered by subjecting the cells to osmotic shock28 in the absence of MgCl2 which is detrimental to TrxA release.29 The protein was purified to near homogeneity by ion exchange chromatography on a Whatman DE52 column. Typical protein concentration was 50 µM (0.67 mg/mL).

Protein Interaction with Carbon Surfaces

All carbon surfaces were characterized by Raman spectroscopy (Supporting Information Fig. S1). Glassy carbon (200–400 µm) spherical powder and explosion diamond powder (210–250 µm) were purchased from SPI Supplies. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWNT; 6–9 nm × 5 µm) synthesized by catalytic chemical vapor deposition were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. For carbon allotrope discrimination experiments, glassy carbon and diamond powders were transferred to a 20 mL glass vial, washed with acetone, methanol and ddH2O, and subjected to three additional wash cycles in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5. Liquid was removed by aspiration and powders were dispensed into microcentrifuge tubes so that each sample corresponded to equivalent surface area (≈ 2,500 mm2). The latter was determined by measuring average particle diameter through microscopy analysis and calculating their surface area by assuming that they were nonporous, perfect spheres. Proteins (250µL from a 2.5µM solution) were added to the powders and the mixtures were incubated for 1h at room temperature. The supernatant was removed and the powders were washed twice with sodium phosphate buffer. The remaining liquid was removed by aspiration and powders were mixed with 675 µL of active reagent from Pierce bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Thermo Scientific). Adsorbed proteins were quantified using a calibration curve constructed with bovine serum albumin, as described by the manufacturer. For MWNT resuspension experiments, ≈ 1 mg of material was added to a glass vial containing 3 mL of protein at 2.5 µM. The mixture was cooled by immersion in a mixture of EtOH and ice and subjected to 2 min of sonication with a micro-tipped sonicator at 12W, 100% duty cycle (Branson Sonifier 450).

Analytical Techniques

QCM measurements were performed on a KSV Z500 instrument using a custom-build Teflon liquid cell and 5 MHz Au quartz crystals (International Crystal Manufacturing) onto which carbon had been evaporated. Before each experiment, crystals were rinsed with ethanol and subjected to UV-ozone treatment for 20 min in a UVO-cleaner (Jelight Co). After addition of 1mL of sodium phosphate buffer, the 3rd, 5th and 7th harmonic frequency changes were monitored until equilibrium was reached (20–30 min) Aliquots of protein (≈ 2, 5, 10 and 20 µL, increasing as maximum surface coverage was approached) were injected and the system was allowed to return to equilibrium. The process was repeated until the protein concentration reached 840 nM. QCM frequency response data and linear least-squares regression was used to construct a Langmuir adsorption isotherm and deduce the values for maximum frequency change (Δfmax at full monolayer coverage) and equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd). By using the calculated values for Δfmax we were able to plot the surface coverage from the knowledge of Δf at each protein concentration.

Surface Plasmon Resonance measurements were conducted on homemade SPR glass chips coated with a ≈ 2 nm titanium adhesion layer, a ≈ 48 nm evaporated gold film, and a ≈ 4 nm evaporated carbon film. Chips were cleaned with ethanol and UV-ozone as above and mounted on a 4-channel flow cell SPR sensor from the Institute of Photonics and Electronics (Prague, Czech Republic) includes temperature control (25 °C) and a peristaltic pump for controlled flow at 50 µL/min. The SPR design is based on an attenuated total reflection and measures wavelength modulation. We note that because carbon coating attenuates the plasmon, SPR data cannot be used to determine absolute protein concentration at the surface but as a relative measurement of binding affinity.30

For atomic force microscopy (AFM), highly oriented pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) substrates (10 × 10 × 2 mm; SPI supplies) were cleaved with adhesive tape to reveal a pristine graphite surface and 150 µL of protein solution at the indicated concentration was deposited by pipetting. After 10 min, the chip was rinsed for 30 sec with ddH2O using a squeeze flask and dried with filtered air. AFM images were collected in tapping mode on a Veeco Multimode V AFM with Veeco TESP Si (Sb) doped cantilevers.

RESULTS

Identification of Carbon Binding Peptides

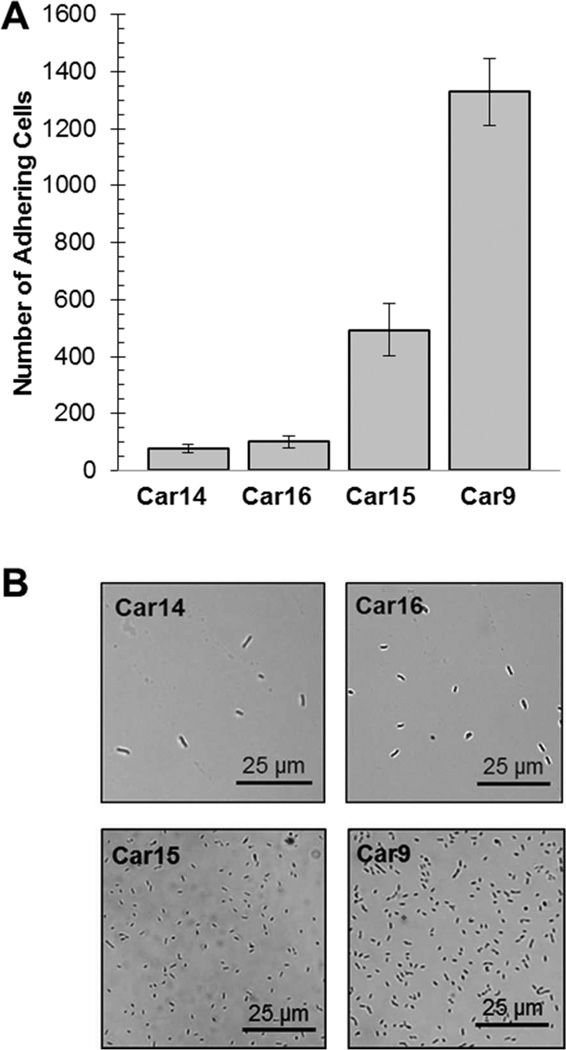

We used the FliTrx flagellar display system31 to identify disulfide-constrained dodecapeptides capable of conferring to E. coli the ability to adhere to evaporated carbon, a disordered and sp2-hybridized material.32 As typically observed when biopanning on inorganic targets,6–8 the putative carbon-binding (Car) peptides did not converge towards a consensus sequence when the inserts of over 30 clones were sequenced. Also as expected,26 there were large differences in the avidity of cell surface displayed Car sequences for carbon. In fact, we observed an almost 20-fold difference in the number of E. coli binding to carbon chips when different Car peptides were displayed on the cell surface within the context of defective flagella (Table 1; Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Physico-chemical characteristics of selected carbon binding peptides

| Name | Sequencea | Mr (Da) | pI | Hydropathyb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Car9 | 1346.6 | 11.1 | −1.900 | |

| Car14 | 1200.3 | 4.3 | +0.267 | |

| Car15 | 1431.8 | 8.8 | +0.525 | |

| Car16 | 1409.6 | 9.6 | −1.000 |

Amino acids are color-coded as follows: hydrophobic, gray; acidic, red; basic, cyan; hydroxyl side chain, green; aromatic (yellow). Invariant tripeptides flanking the dodecamers are italicized.

Average hydropathy score are based on the Kyte and Doolittle scale.53 Positive scores denote hydrophobic sequences while negative scores denote hydrophilic sequences. The higher (respectively, lower) the score, the more hydrophobic (respectively, hydrophilic) the sequence is.

Figure 1.

Adhesion of cells expressing different carbon-binding peptides on their flagella to carbon-coated surfaces. (A) E. coli GI826 cells harboring plasmids encoding the indicated FliC∷Trx∷Car fusions (where Car denotes a carbon binding peptide) were contacted with carbon-coated cover slips. After washing, slides were transferred to the stage of a microscope and the number of cells present in a field was counted at 500-fold magnification. Error bars were obtained for 5 different fields and two separate experiments. (B) Characteristic appearance of carbon-coated slides following incubation with cells expressing low (Car14, Car16), moderate (Car15) or high avidity (Car9) carbon binding peptides on their flagella.

Two of the sequences found to promote high-avidity cell binding (Car9 and Car15) contained a tyrosine (Y) and Car15 also specified tryptophan (W). The presence of aromatic amino acids, in particular that of tryptophan, was not unexpected since these residues have previously been implicated in mediating the binding of peptides to carbon nanotubes, carbon nanohorns and graphene surfaces via π-stacking.21,23,24,33–37 On the other hand, Car14 led to poor cell adhesion in spite of containing a tryptophan and the aromatic-free Car16 sequence was capable of mediating (weak) cell adhesion to carbon substrates.

Construction and Purification of Carbon-Binding Designer Proteins

To better understand how two sequences of distinct pI and hydrophobicity (Table 1) can both confer high-avidity binding to carbon surfaces, we constructed derivatives of E. coli Thioredoxin 1 (TrxA) containing a disulfide-constrained Car9 or Car15 sequence in place of the native Cys-Gly-Pro-Cys active site. The TrxA scaffold has the advantages of being fully compatible with the FliTrx system31 and of projecting its active site loop outwards,38 which allows for efficient contact between inserted solid binding peptides and their cognate materials.

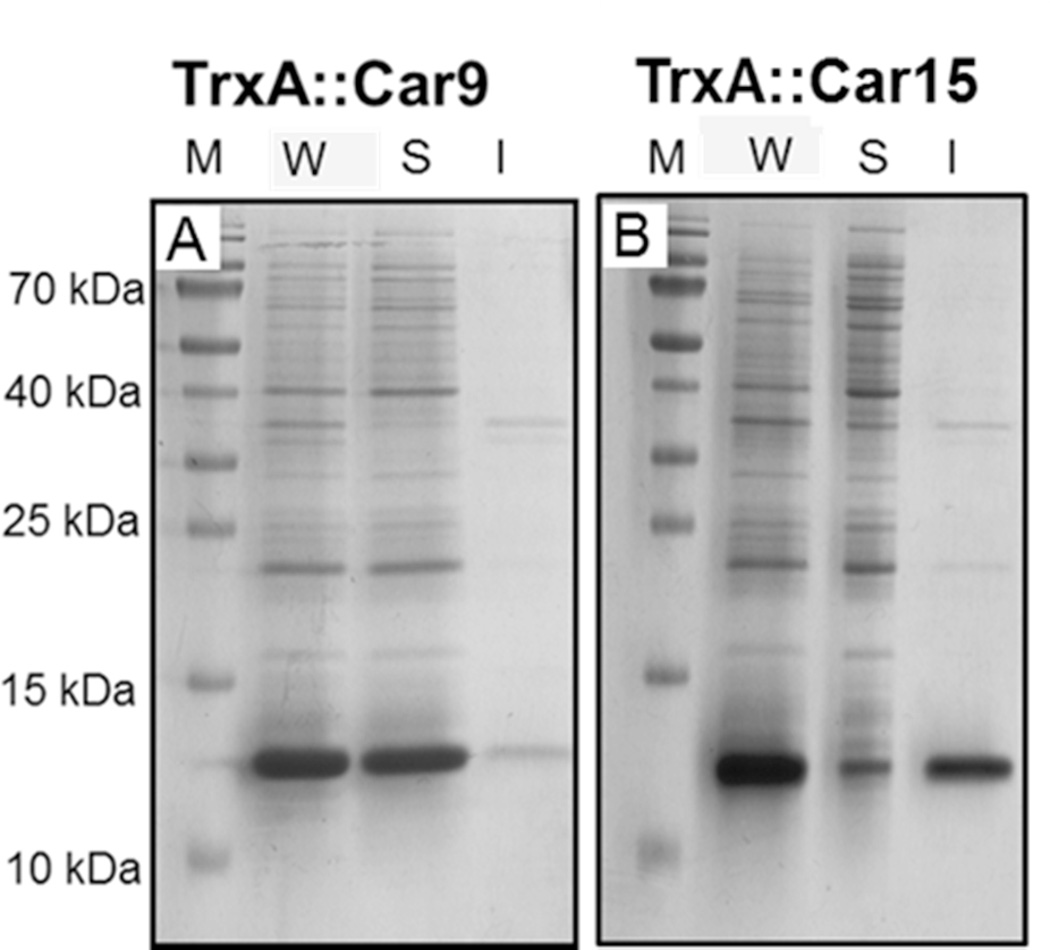

Fig. 2A shows that the TrxA∷Car9 fusion protein was indeed almost completely soluble. It could be rapidly purified by incubating crude cell extracts at high temperature in order to precipitate thermolabile host proteins and recovering the target protein in a nearly pure form by anion exchange chromatography, as described.27 By contrast, nearly 85% of the total TrxA∷Car15 produced was found in the insoluble cell fraction (Fig. 2B), even though cells were cultured at 25°C to minimize protein misfolding.39 Such aggregation-prone behavior is consistent with the much higher overall hydrophobicity of the Car15 sequence compared to Car9. Yet, the fact that 15% of the total protein produced is soluble indicates that Car15 can pack its hydrophobic core in a conformation that does not promote inclusion body formation.

Figure 2.

Solubility of carbon-binding TrxA derivatives. E. coli BL21(DE3) cells harboring plasmids encoding the TrxA∷Car9 (A) or TrxA∷Car15 (B) fusion proteins were grown, induced and harvested as described in Methods. Whole cells (W) were separated into soluble (S) and insoluble (I) fractions and samples corresponding to identical amount of cells were resolved on reducing SDS minigels.

In order to selectively purify these TrxA∷Car15 conformers, we took advantage of the observation that authentic TrxA can be released from the E. coli cytoplasm by an osmotic shock procedure that is normally used to purify periplasmic proteins.28 The presence of the Car15 sequence had no noticeable on impact on the osmotic release of TrxA (which is believed to occur through mechano-sensitive channels in the E. coli inner membrane)29 and we were able to recover soluble and pure TrxA∷Car15 by subjecting the osmotic shock fluid to a single anion exchange chromatography step.

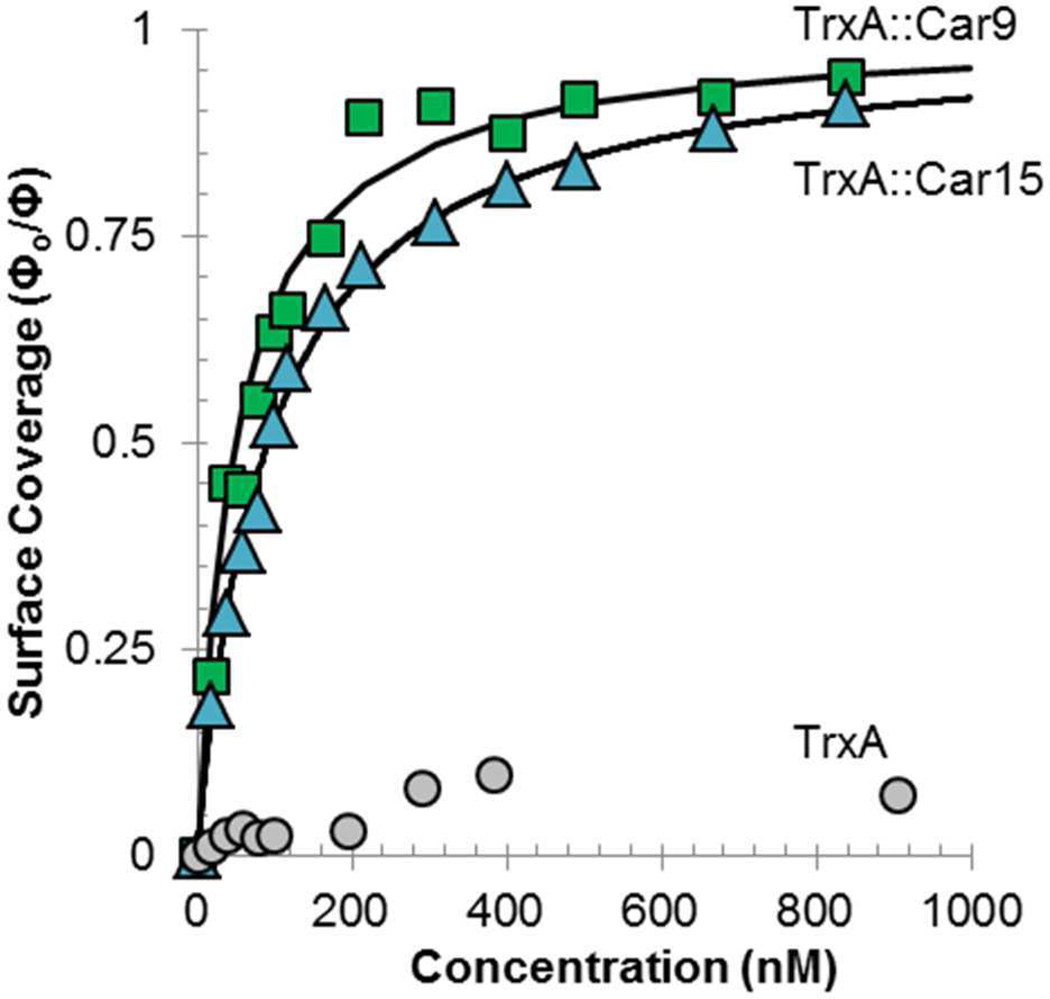

TrxA∷Car9 and TrxA∷Car15 Adsorb to Evaporated Carbon through Distinct Mechanisms

We next quantified the affinity of the purified designer proteins for carbon by quartz microbalance (QCM) measurements using QCM crystals that had been coated with an evaporated carbon film (an amorphous, but mostly sp2-hybridized surface).40 Fig. 3 shows that while the “empty” TrxA framework had little to no affinity for this substrate, the presence of Car9 or Car15 led to high affinity binding with calculated equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd) of 50 nM for TrxA∷Car9, and 90 nM for TrxA∷Car15. These values are comparable to one another and typical of the room temperature Kd measured with other inorganic-binding designer proteins on their cognate substrates.41–45

Figure 3.

QCM analysis of the adsorption of carbon-binding TrxA derivatives to amorphous carbon. Authentic TrxA (circles), TrxA∷Car9 (squares) or TrxA∷Car15 variants (triangles) were incubated at the indicated concentrations on carbon-coated QCM crystals. Fractional surface coverages were determined as described in Methods. Solid lines correspond to Langmuir isotherms from which equilibrium dissociation constants were extracted.

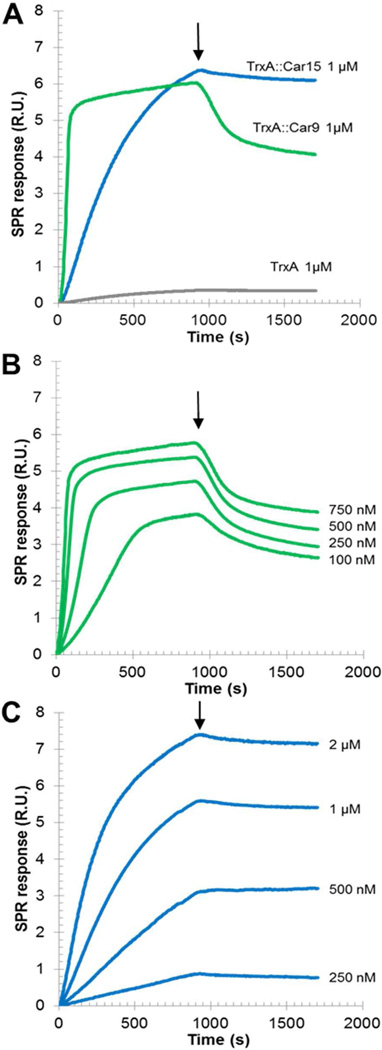

To gain further information on the nature of binding, we evaporated a thin carbon film onto a gold-coated glass chip and conducted surface plasmon resonance (SPR) measurements with this substrate using a multichannel flow cell. As expected from QCM results, authentic TrxA did not significantly interact with the carbon surface when flowed over the SPR chip at a concentration of 1 µM and a flow rate of 50 µL/min (Fig. 4A, gray). Under the same conditions, TrxA∷Car9 (green) rapidly adsorbed and did so with sigmoidal initial kinetics that became more obvious when the protein concentration was lowered to 100 nM (Fig. 4B). Such behavior is typically indicative of a cooperative adsorption mechanism.46 By comparison, TrxA∷Car15 bound to carbon with typical first order kinetics but did so with a lower kon adhesion rate (Fig. 4C). In addition, the two proteins exhibited very different desorption behaviors: while about a third of TrxA∷Car9 could be removed from the surface upon washing with buffer (Fig. 4A–B, arrow), TrxA∷Car15 remaining quantitatively bound to the substrate (Fig. 4A and C). Equilibrium dissociation constants extracted from these data (see Supporting Information Fig. S2) were 40 nM for TrxA∷Car9 and 85 nM for TrxA∷Car15, in very good agreement with QCM measurements. Taken together, the above data suggest that although the Car9 and Car15 carbon binding peptides confer TrxA similar affinity for amorphous carbon under equilibrium conditions, the underlying adsorption mechanisms are distinct.

Figure 4.

SPR analysis of the adsorption of carbon-binding TrxA derivatives to amorphous carbon.. (A) Authentic TrxA (grey), TrxA∷Car9 (green) or TrxA∷Car15 variants (blue) were flowed over a carbon-coated SPR chip at 1 µM concentration. Pure buffer was flowed after 15 min (arrows). Sensograms were obtained at the indicated concentrations of TrxA∷Car9 (B) or TrxA∷Car15 (C) for Kd calculation. See text and supplementary information for details.

Car15 is an Effective Graphene Binding Peptide

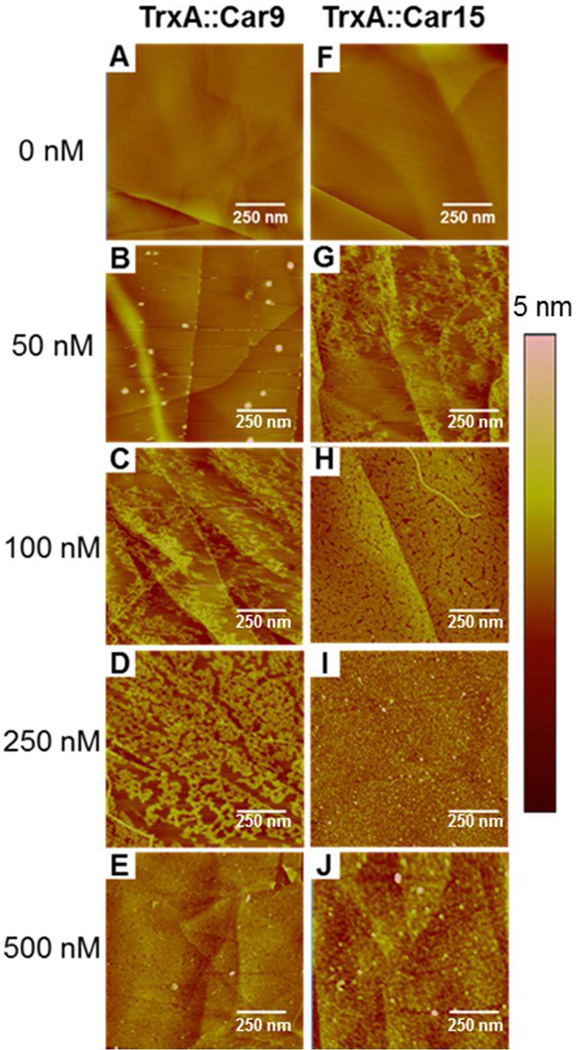

We turned to atomic force microscopy (AFM) to better understand how Car15 and Car9 mediate the attachment of TrxA to carbon. Because the surface roughness of evaporated carbon (> 5 nm) would have complicated the analysis, we imaged the adsorption of TrxA∷Car9 and TrxA∷Car15 at five different concentrations on highly ordered pyrolytic graphite (HOPG), a multilayered sp2–hybridized material with surface chemistry and long-range order similar to that of graphene. At a concentration of 50 nM, TrxA∷Car9 formed discrete aggregates on HOPG terraces and preferentially adhered to the high-energy step edges (Fig. 5C). TrxA∷Car15 was more evenly distributed with no distinct preference for edges or terraces (Fig. 5G; Supporting Information Fig. S3C–D). At 100 nM, TrxA∷Car15 nearly achieved monolayer coverage (Fig. 5H). Surface decoration remained incomplete with TrxA∷Car9 under the same conditions and it seemed to proceed from the edges and onto the terraces as the protein concentration increased (Fig. 5C–D; Supporting Information Fig. S3A–B). Complete surface coverage was reached at 500 nM TrxA∷Car9 (Fig. 5E) and 250 nM TrxA∷Car15 (Fig. 5I). Of note, control experiments conducted with wild type TrxA showed that the protein framework did not adhere to HOPG in the absence of inserted Car sequences at concentrations as high as 1 µM (Supporting Information Fig. S4).

Figure 5.

AFM analysis of the adsorption of carbon-binding TrxA derivatives to HOPG. TrxA∷Car9 (A–E) or TrxA∷Car15 (F–J) in 50 mM phosphate buffer and at the indicated concentrations were contacted for 10 min with freshly cleaved HOPG. Surfaces were imaged by AFM after washing and drying. The scale bar corresponds to 250 nm.

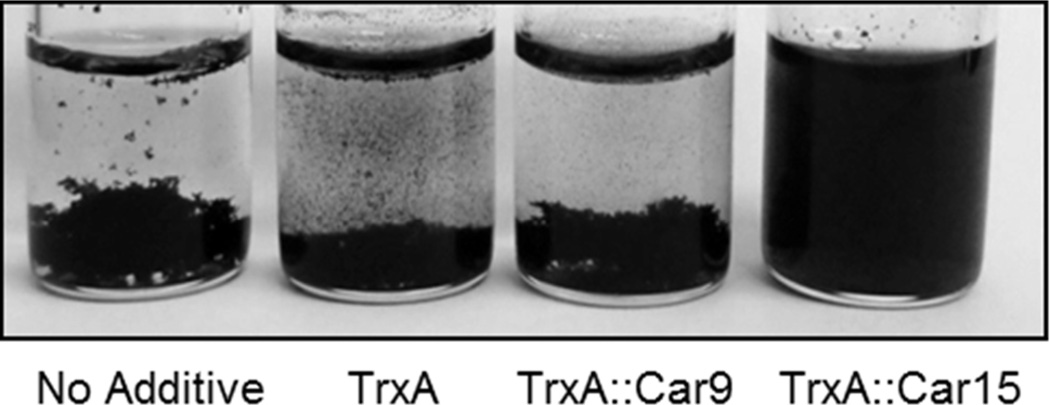

We reasoned that if TrxA∷Car15 binds to sp2-hybridized carbon more efficiently than TrxA∷Car9, it should also prove superior at dispersing graphene nanostructures that tend to aggregate in polar solvents due to their high surface area and hydrophobicity. To test this hypothesis, approximately 1 mg of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWNTs) was sonicated in buffer alone or in the presence of ≈ 2.5 µM of TrxA, TrxA∷Car9 or TrxA∷Car15, and the solutions were allowed to stand at room temperature for 24h. Consistent with our expectations, TrxA∷Car15 was the only protein capable of maintaining the nanotubes in suspension (Fig. 6). We conclude that Car15 binds to graphitic surfaces with high-affinity and specificity and that it can be used at low concentration to solubilize MWNTs, and, presumably, other sp2-bonded carbon nanostructures of engineering interest.

Figure 6.

Dispersion of multi-walled carbon nanotubes by carbon-binding TrxA derivatives. MWNT (≈ 1mg) were sonicated in the absence of additive or in the presence of 2.5 µM of authentic TrxA, TrxA∷Car9 or TrxA∷Car15. Samples were photographed after 24h.

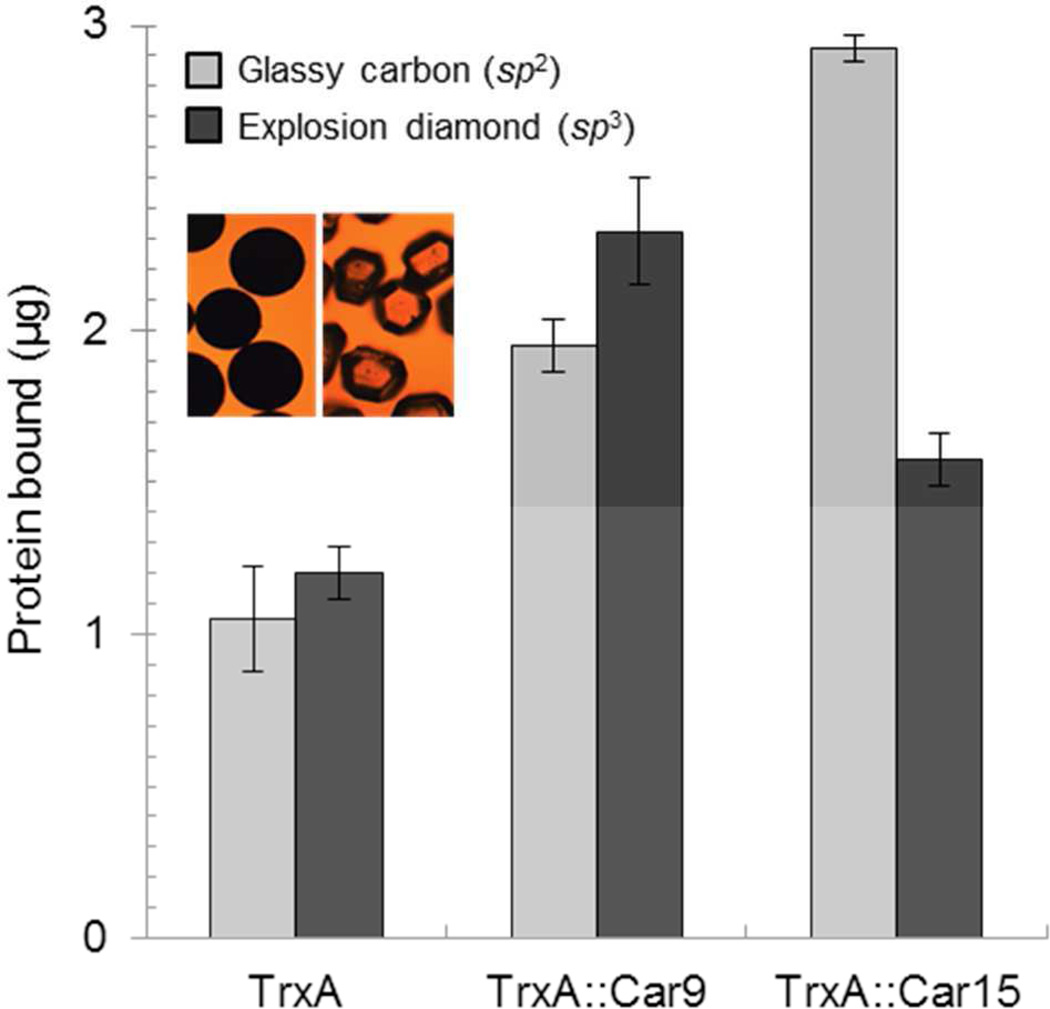

Carbon Allotrope Discrimination

Graphite and graphene are sp2-bonded materials in which carbon atoms are arranged into planar hexagonal rings. In diamond, the other naturally abundant form of crystalline carbon, atoms are sp3-hybridized and organized as two interpenetrating face-centered cubic (FCC) lattices. To determine if Car9 and Car15 would exhibit selectivity for these two carbon allotropes, we acquired glassy carbon (a nonporous, fullerene-related and sp2-bonded material)47 and explosion diamond powders in the same size range (200–400 µm). We calculated the average surface area per weight for both substrates using microscopy analysis and assuming a spherical geometry for both particles (Fig. 7, inset). Next, we incubated the cleaned powders at equivalent surface area (2,500 mm2) with 2.5 µM of TrxA, TrxA∷Car9 or TrxA∷Car15 and used a standard BCA assay to determine how much protein remained particle-bound after two cycles of washing. Under these conditions, comparable amounts (≈ µg) of authentic TrxA adsorbed to both powders through non-specific interactions (Fig. 7). While the presence of a Car9 insert nearly doubled the amount of protein bound to either powder, there was no statistical difference in the ability of TrxA∷Car9 to recognize sp2-over sp3-hybridized carbon. By contrast, about 3 µg of TrxA∷Car15 adsorbed to glassy carbon compared to ≈ 1.5 µg on diamond, leading to a 2:1 discrimination factor between the two carbon allotropes.

Figure 7.

Adsorption of carbon-binding TrxA derivatives to sp2- and sp3-hybridized carbon powders. Authentic TrxA, TrxA∷Car9 or TrxA∷Car15 (2.5 µM) were incubated for 1h with glassy carbon or explosion diamond powders at equivalent surface areas. The amount of bound protein remaining after washing was determined by BCA assay. Insets show the appearance of the glassy carbon (left) and detonation diamond (right) powders.

DISCUSSION

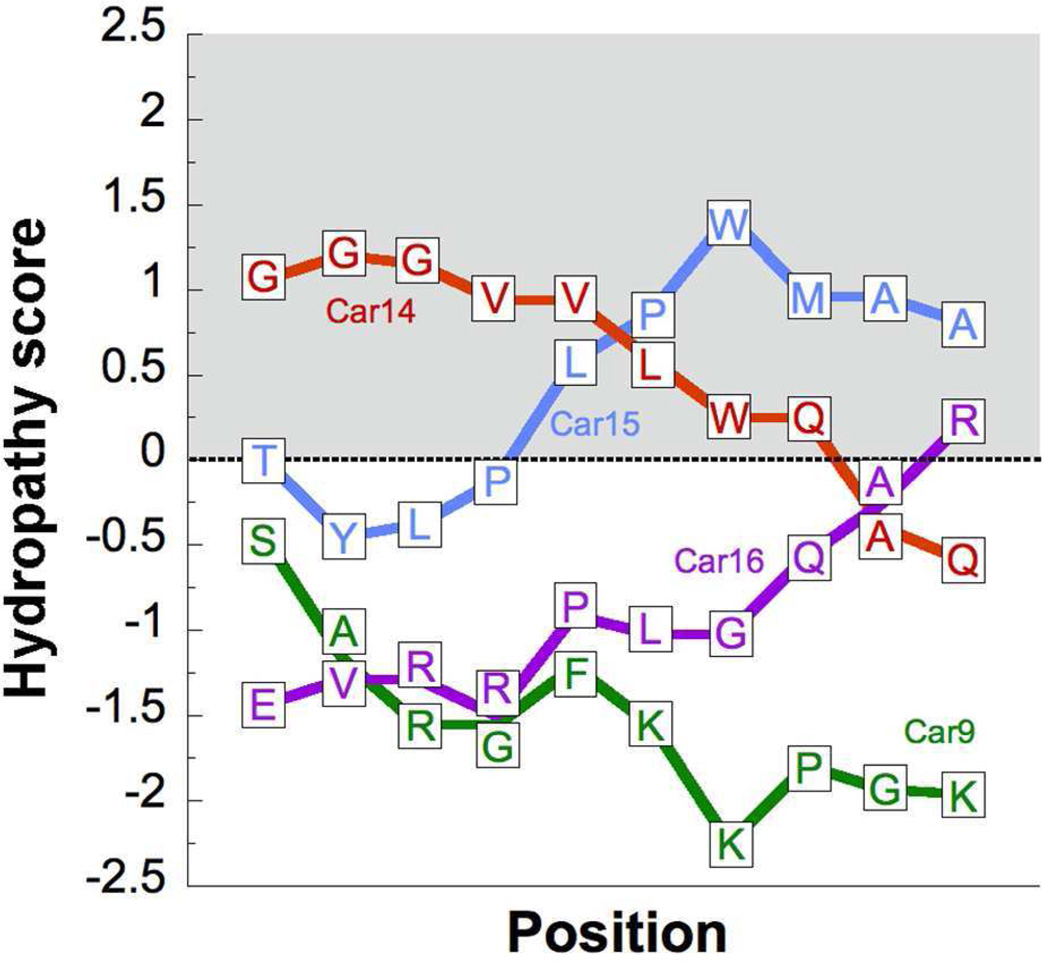

As previously observed by other investigators in the case of C60-specific antibodies,48 and designed19,20 and selected21–25 graphene-binding peptides, we found that the aromatic residues tryptophan, tyrosine and phenylalanine were important to drive the high-affinity binding of displaying cells to amorphous carbon, presumably because these amino acids are capable of forming π-π interactions with sp2-hybridized regions. Nevertheless, neither the presence of a strong physisorbing amino acid such as tryptophan,34–36 nor that of a local region of high hydrophobicity guarantees efficient carbon binding (see, e.g. Car14; Fig. 1 and 8). In fact, cells displaying peptides that completely lack aromatic content and are reasonably hydrophilic (e.g., Car16; Fig 8) are still capable of weakly adhering to carbon, perhaps because their sequences are enriched in basic residues (arginine and lysine) that interact with negatively charged hydroxyl, carbonyl, ether and ketone groups dangling from the edge of sp2-hybridized domains at pH 7.5.49

Figure 8.

Positional dependency of the hydrophobicity in carbon-binding peptides. The local hydrophobicity of the indicated Car sequences flanked by invariant tripeptides (Table 1) was determined with the ExPASy ProtScale tool (http://web.expasy.org/protscale/) using the Kyte and Doolittle hydrophobicity scale53 and a sliding window of 9 residues (thus, the first calculated hydropathy score is for the second residue of a Car dodecapeptide). Positive scores denote hydrophobic character.

Compared to solid-binding peptides, cells and viruses, solid-binding proteins offer the advantages of multiple SBP insertion with positional control of placement, addition of biological functionalities (e.g., ligand binding, enzymatic activity, etc) via genetic engineering, and solubility enhancement.1 The latter is particularly true of TrxA, a small, fast-folding, and thermostable protein that has a long history of improving the solubility of aggregation-prone fusion partners.50,51 Here, we found that insertion of the Car15 sequence within the active site loop of TrxA greatly compromised its ability to fold (Fig. 5). Clearly, if hydrophobic sequences such as Car15 are insoluble within the context of TrxA, it is hard to imagine how they could be fully soluble as synthetic peptides and at the concentrations (typically 100µM to 3 mM) where studies with synthetic carbon-binding peptides are often performed. However, by taking advantage of the unusual ability of TrxA to partition with periplasmic contents upon osmotic shock,29 we were able to selectively purify the soluble (and thus properly folded) subpopulation of TrxA∷Car15 conformers. The availability of this protein and that of the easily purified TrxA∷Car9 allowed us to conduct a detailed analysis of the interactions of two otherwise isogenic carbon-binding proteins with various carbon surfaces.

While the high affinity of Car15 for carbon is well explained by the “classic” theory – a region of high local hydrophobicity with a π-π–hybridizing tryptophan at its core24,35 – that of Car9 is more likely to originate from a combination of electrostatic interactions (between arginine and lysine residues and negatively charged dangling groups) and weaker36 π-stacking between phenylalanine and sp2-bonded carbon rings. Such differences in adsorption mechanisms are consistent with the first order and tight binding of TrxA∷Car15 to amorphous carbon relative to the sigmoidal adsorption kinetics and weaker binding that we observed with TrxA∷Car9 by SPR (Fig. 4B). They also account for the higher propensity of TrxA∷Car9 to decorate HOPG step edges relative to TrxA∷Car15 (Fig. 5 and Supporting Information Fig. S3). Indeed, electrostatic interactions have been proposed to play an important role in the preferential binding of an aromatic-free peptide to the edges of graphene.52

These distinct adsorption modalities have important practical implications for the dispersion, functionalization and manipulation of carbon (nano)structures as well as for the selective recognition of carbon allotropes (Fig. 6–7). For instance, TrxA∷Car15 binds with a high degree of specificity to sp2-hybridized carbon and is thus highly suitable for solubilizing carbon nanotubes. By contrast, the reliance of TrxA∷Car9 on electrostatics for carbon binding means that although it is suitable for functionalizing both glassy carbon and diamond, it cannot stably disperse nanotubes. It will be interesting to determine if the Car9 and Car15 carbon binding peptides will be useful to achieve direct asymmetric functionalization of the ends/edges and sides/planes of carbon nanotubes and graphene nanostructures with proteins.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we used cell surface display to isolate a new set of carbon binding peptides and conducted a detailed characterization of two of these sequences within the context of TrxA fusion proteins. We showed that equivalent carbon binding affinities can be achieved through very different adsorption kinetics and molecular recognition mechanisms, and demonstrated a direct correlation between adsorption modality, carbon nanostructure dispersion and carbon allotrope discrimination. Furthermore, as we will report elsewhere, the Car15 and Car9 sequences are fully functional for carbon binding when fused to other protein frameworks. By relying on this property and a growing understanding of carbon-peptide interactions, it should be possible to build designer proteins that provide full control over carbon nanostructure functionalization, manipulation and assembly towards powerful bio-enabled electronics and sensors.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Corrine Thai for helping with the isolation of carbon binding peptides, Ikechukwu Nwaneshiudu for help with Raman spectroscopy, and Stephanie Vasko for help with some of the initial AFM imaging. This work was supported by ONR through the Carbon Molecular Electronics Basic Research Challenge (BRC-11123566), NIH through a U19 award (U19ES019545), and NSF through the Genetically Engineered Materials Science and Engineering Center (DMR-0520567). Part of this work was conducted at the University of Washington Nanotech User Facility, a member of the NSF National Nanotechnology Infrastructure Network (NNIN).

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

Carbon surfaces characterized by Raman spectroscopy (Figure S1). Determination of Kd by surface plasmon resonance (Figure S3). Additional AFM images of the adsorption of carbon-binding TrxA derivatives onHOPG (Figure S3). AFM images of HOPG after incubation with buffer or authentic TrxA (Figure S4). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Coyle B, Zhou W, Baneyx F. Protein-Aided Mineralization of Inorganic Nanostructures. In: Rehm BHA, editor. Bionanotechnology: Biological Self-Assembly and Its Applications. Norwich, U.K.: Caister Academic Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dickerson MB, Sandhage KH, Naik RR. Protein- and Peptide Directed Synthesis of Inorganic Materials. Chem Rev. 2008;108:4935–4978. doi: 10.1021/cr8002328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee S-Y, Lim J-S, Harris MT. Synthesis and Application of Virus-Based Hybrid Nanomaterials. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109:16–30. doi: 10.1002/bit.23328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seker UOS, Demir HV. Material Binding Peptides for Nanotechnology. Molecules. 2011;16:1426–1451. doi: 10.3390/molecules16021426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soto CM, Ratna BR. Virus Hybrids as Nanomaterials for Biotechnology. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2010;21:426–438. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baneyx F, Schwartz DT. Selection and Analysis of Solid-Binding Peptides. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2007;18:312–317. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarikaya M, Tamerler C, Jen AK, Schulten K, Baneyx F. Molecular Biomimetics: Nanotechnology through Biology. Nat Mater. 2003;2:577–585. doi: 10.1038/nmat964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarikaya M, Tamerler C, Schwartz DT, Baneyx F. Materials Assembly and Formation Using Engineered Polypeptides. Annu Rev Mater Res. 2004;34:373–408. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geim AK. Graphene: Status and Prospects. Science. 2009;324:1530–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.1158877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo S, Dong S. Graphene Nanosheet: Synthesis, Molecular Engineering, Thin Film, Hybrids, and Energy and Analytical Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:2644–2672. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00079e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qureshi A, Kang WP, Davidson JL, Gurbuz Y. Review on Carbon-Derived, Solid-State, Micro and Nano Sensors for Electrochemical Sensing Applications. Diam Rel Mater. 2009;18:1401–1420. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu J, Pisula W, Mullen K. Graphenes as Potential Material for Electronics. Chemical Reviews. 2007;107:718–718. doi: 10.1021/cr068010r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Z, Tabakman S, Welsher K, Dai H. Carbon Nanotubes in Biology and Medicine: In Vitro and in Vivo Detection, Imaging and Drug Delivery. Nano Res. 2009;2:85–120. doi: 10.1007/s12274-009-9009-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen H, Zhang L, Liu M, Zhang Z. Biomedical Applications of Graphene. Theranostics. 2012;2:283–294. doi: 10.7150/thno.3642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Li Z, Wang J, Li J, Lin Y. Graphene and Graphene Oxide: Biofunctionalization and Applictions in Biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 2011;29:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boul P, Liu J, Mickelson E, Huffman C, Ericson L, Chiang I, Smith K, Colbert D, Hauge R, Margrave J. Reversible Sidewall Functionalization of Buckytubes. Chem Phys Lett. 1999;310:367–372. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan WCW, Nie S. Quantum Dot Bioconjugates for Ultrasensitive Nonisotopic Detection. Science. 1998;281:2016–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vigolo B, Penicaud A, Coulon C, Sauder C, Pailler R, Journet C, Bernier P, Poulin P. Macroscopic Fibers and Ribbons of Oriented Carbon Nanotubes. Science. 2000;290:1331–1334. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5495.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dieckmann GR, Dalton AB, Johnson PA, Razal J, Chen J, Giordano GM, Munoz E, Musselman IH, Baughman RH, Draper RK. Controlled Assembly of Carbon Nanotubes by Designed Amphiphilic Peptide Helices. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:1770–1777. doi: 10.1021/ja029084x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ortiz-Acevedo A, Xie H, Zorbas V, Sampson WM, Dalton AB, Baughman RH, Draper RK, Musselman IH, Dieckmann GR. Diameter-Selective Solubilization of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes by Reversible Cyclic Peptides. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9512–9517. doi: 10.1021/ja050507f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cui Y, Kim SN, Jones SE, Wissler LL, Naik RR, McAlpine MC. Chemical Functionalization of Graphene Enabled by Phage Displayed Peptides. Nano Lett. 2010;10:4559–4565. doi: 10.1021/nl102564d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh D, Dang X, Yi H, Allen MA, Xu K, Lee YJ, Belcher AM. Graphene Sheets Stabilized on Genetically Engineered M13 Viral Templates as Conducting Frameworks for Hybrid Energy-Storage Materials. Small. 2012;8:1006–1011. doi: 10.1002/smll.201102036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.So CR, Hayamizu Y, Yazici H, Gresswell C, Khatayevich D, Tamerler C, Sarikaya M. Controlling Self-Assembly of Engineered Peptides on Graphite by Rational Mutation. ACS Nano. 2012;6:1648–1656. doi: 10.1021/nn204631x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang S, Humphreys ES, Chung S-Y, Delduco DF, Lustig SR, Wang H, Parker KN, Rizzo NW, Subramoney S, Chiang Y-M, Jagota A. Peptides with Selective Affinity for Carbon Nanotubes. Nat Mater. 2003;2:196–200. doi: 10.1038/nmat833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu T, Gong Y, Lu T, Wei L, Li Y, Mu Y, Chen Y, Liao K. Recognition of Carbon Nanotube Chirality by Phage Display. RSC Adv. 2012;2:1466–1476. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thai CK, Dai H, Sastry MS, Sarikaya M, Schwartz DT, Baneyx F. Identification and Characterization of Cu2O- and Zno-Binding Polypeptides by Escherichia Coli Cell Surface Display: Toward an Understanding of Metal Oxide Binding. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;87:129–137. doi: 10.1002/bit.20149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou W, Schwartz DT, Baneyx F. Single Pot Biofabrication of Zinc Sulfide Immuno-Quantum Dots. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:4731–4738. doi: 10.1021/ja909406n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nossal NG, Heppel LA. The Release of Enzymes by Osmotic Shock from Escherichia Coli in Exponential Phase. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:3055–3062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lunn CA, Pigiet VP. Localization of Thioredoxin from Escherichia Coli in an Osmotically Sensitive Compartment. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:11424–11430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Homola J. Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensors for Detection of Chemical and Biological Species. Chem Rev. 2008;108:462–493. doi: 10.1021/cr068107d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu Z, Murray KS, Van Cleave V, LaVallie ER, Stahl ML, McCoy JM. Expression of Thioredoxin Random Peptide Libraries on the Escherichia Coli Cell Surface as Functional Fusions to Flagellin: A System Designed for Exploring Protein-Protein Interactions. Biotechnology. 1995;13:366–372. doi: 10.1038/nbt0495-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robertson J. Diamond-Like Amorphous Carbon. Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports. 2002;37:129–281. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kase D, Kulp JL, 3rd, Yudasaka M, Evans JS, Iijima S, Shiba K. Affinity Selection of Peptide Phage Libraries against Single-Wall Carbon Nanohorns Identifies a Peptide Aptamer with Conformational Variability. Langmuir. 2004;20:8939–8941. doi: 10.1021/la048968m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su Z, Mui K, Daub E, Leung T, Honek J. Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Binding Peptides: Probing Tryptophan's Importance by Unnatural Amino Acid Substitution. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:14411–14417. doi: 10.1021/jp0740301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomásio SM, Walsh TR. Modeling the Binding Affinity of Peptides for Graphitic Surfaces. Influence of Aromatic Content and Interfacial Shape. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113:8778–8785. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xie H, Becraft EJ, Baughman RH, Dalton AB, Dieckmann GR. Ranking the Affinity of Aromatic Residues for Carbon Nanotubes by Using Designed Surfactant Peptides. Journal of peptide science: an official publication of the European Peptide Society. 2008;14:139–151. doi: 10.1002/psc.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zorbas V, Smith AL, Xie H, Ortiz-Acevedo A, Dalton AB, Dieckmann GR, Draper RK, Baughman RH, Musselman IH. Importance of Aromatic Content for Peptide/Single Wall Carbon Nanotube Interactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12323–12328. doi: 10.1021/ja050747v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katti SK, LeMaster DM, Eklund H. Crystal Structure of Thioredoxin from Escherichia Coli at 1.68 a Resolution. J Mol Biol. 1990;212:167. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90313-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baneyx F. Recombinant Protein Expression in Escherichia Coli. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1999;10:411–421. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(99)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferrari AC, Robertson J. Raman Spectroscopy of Amorphous, Nanostructured, Diamond-Like Carbon, and Nanodiamond. Philos Transact A. 2004;362:2477–2512. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2004.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dai H, Choe WS, Thai CK, Sarikaya M, Traxler BA, Baneyx F, Schwartz DT. Nonequilibrium Synthesis and Assembly of Hybrid Inorganic-Protein Nanostructures Using an Engineered DNA Binding Protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15637–15643. doi: 10.1021/ja055499h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grosh C, Schwartz DT, Baneyx F. Protein-Based Control of Silver Growth Habit Using Electrochemical Deposition. Cryst Growth Des. 2009;9:4401–4406. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kitayaporn S, Zhou W, Schwartz DT, Baneyx F. Laying out Ground Rules for Protein-Aided Nanofabrication: Zno Synthesis at 70ºc as a Case Study. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109:1912–1918. doi: 10.1002/bit.24466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sedlak RH, Hnilova M, Grosh C, Fong H, Baneyx F, Schwartz D, Sarikaya M, Tamerler C, Traxler B. Engineered Escherichia Coli Silver-Binding Periplasmic Protein That Promotes Silver Tolerance. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2012;78:2289–2296. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06823-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sengupta A, Thai CK, Sastry MSR, Schwartz DT, Davis EJ, Baneyx F. A Genetic Approach for Controlling the Binding and Orientation of Proteins on Nanoparticles. Langmuir. 2008;24:2000–2008. doi: 10.1021/la702079e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burghardt TP, Axelrod D. Total Internal Reflection/Fluorescence Photobleaching Recovery Study of Serum Albumin Adsorption Dynamics. Biophysical journal. 1981;33:455–467. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(81)84906-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harris PJF. Fullerene-Related Structure of Commercial Glassy Carbons. Philos Mag. 2004;84:3159–3167. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Braden BC, Goldbaum FA, Chen BX, Kirschner AN, Wilson SR, Erlanger BF. X-Ray Crystal Structure of an Anti-Buckminsterfullerene Antibody Fab Fragment: Biomolecular Recognition of C(60) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12193–12197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.210396197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang DQ, Sacher E. Interaction of Evaporated Nickel Nanoparticles with Highly Oriented Pyrolytic Graphite: Back-Bonding to Surface Fefects, as Studied by X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:19329–19334. doi: 10.1021/jp0536504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holmgren A. Thioredoxin. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 1985;54:237–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.LaVallie ER, Lu Z, Diblasio EA, Collins-Racie LA, McCoy JM. Thioredoxin as a Fusion Partner for Production of Soluble Recombinant Proteins in Escherichia Coli. Methods Enzymol. 2000;326:322–340. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)26063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim SN, Kuang Z, Slocik JM, Jones SE, Cui Y, Farmer BL, McAlpine MC, Naik RR. Preferential Binding of Peptides to Graphene Edges and Planes. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:14480–14483. doi: 10.1021/ja2042832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A Simple Method for Displaying the Hydropathic Character of a Protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.