Abstract

Objective

This trial evaluated the efficacy of an HIV intervention condition, relative to a health promotion condition, in reducing incidence of non-viral STIs (Chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis), oncogenic HPV subtypes 16 and 18, sexual concurrency, and other HIV-associated behaviors over a 12-month period.

Design

Randomized controlled trial. Data analysts blinded to treatment allocation.

Setting

Kaiser Permanente Georgia

Subjects

A random sample of 848 African American women

Intervention

The two 4-hour HIV intervention sessions were based on Social Cognitive Theory and the Theory of Gender and Power. The intervention was designed to enhance participants’ self sufficiency and attitudes and skills associated with condom use. The HIV intervention also encouraged STI testing and treatment of male sex partners, and reducing vaginal douching and individual and male partner concurrency.

Main Outcome Measure

Incident non-viral STIs.

Results

In GEE analyses, over the 12-month follow-up, participants in the HIV intervention, relative to the comparison, were less likely to have non-viral incident STIs (OR=0.62; 95% CI, 0.40-0.96; P =.033); and incident high-risk HPV infection (OR=0.37; 95% CI, 0.18-0.77; P = .008), or concurrent male sex partners (OR=0.55; 95% CI, 0.37-0.83; P = .005). Additionally, intervention participants were less likely to report multiple male sex partners, more likely to use condoms during oral sex, more likely to inform their main partner of their STI test results, encourage their main partner to seek STI testing, report that their main partner was treated for STIs, and report not douching.

Conclusion

This is the first trial to demonstrate that an HIV intervention can achieve reductions in non-viral STIs, high-risk HPV, and individual concurrency.

Keywords: HIV intervention, HPV, STIs, concurrency, women

INTRODUCTION

HIV is the leading cause of death among African American women ages 25 to 34 years.1 The annual rate of new HIV cases has been increasing among African American women;2 particularly in the Southern U.S.. Seven of the ten states with the highest AIDS case rates for women are in the southern US.3 Southern African American women’s HIV risk may be attributed to the higher prevalence of other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among African Americans in the South 4, vaginal douching,5 which is much more prevalent among African American women in the Southern US6 and having a higher prevalence of concurrent sexual partnerships among African Americans.7

While HIV interventions for women have been published, few address sexual concurrency.8 Translational research is pivotal for reducing racial disparities in health outcomes.9 Translating critical epidemiologic evidence regarding the impact of concurrency on African American women’s HIV vulnerability into the design of HIV interventions tailored for this population could reduce racial disparities in African American women’s vulnerability for HIV. The current trial evaluated the efficacy of an HIV intervention that sought to reduce concurrency, other HIV sexual behaviors, and incident STIs among African-American women in the Southern US.

METHODS

Participants

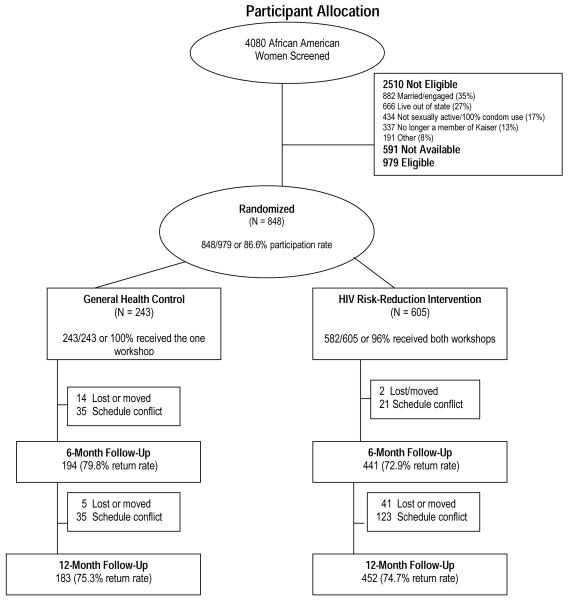

From October 2004 through October 2007, eligible participants were recruited into the trial. Eligibility included being a self-identified African-American woman, 18-29 years of age, unmarried, sexually active in the prior 6 months, and a member of one of three Kaiser Centers in Atlanta, Georgia. Kaiser Permanente is the largest integrated health maintenance organization (HMO) in the US offering individual and family health care plans. During the recruitment period, the Kaiser Permanente subscriber database was used to randomly select 8231 women from the three Kaiser Permanente Centers having the greatest number of African-Americans. Of these subscribers, 4151 (50.4%) did not meet inclusion criteria (were not African-American women or within the specified target age range of 18–29 years). The remaining 4080 women were mailed letters inviting them to participate in the study. Of these, 2510 (61.5%) were not eligible due to study exclusion criteria (currently married, use condoms 100% of the time, want to become pregnant in the next year, or live outside the state); and 591 (14.5%) were not available to participate (i.e. they could not attend both sessions of the intervention due to school or work conflicts). Thus, 979 women (24%) met all criteria, were invited to participate in the study, with 848 (86.6%) completing baseline assessment and randomized to study conditions (Figure 1). Participants were compensated $50 for their time in participating in the baseline and follow-up assessments. The Emory University Institutional Review Board approved the study prior to implementation.

Figure 1.

Participant Allocation

Study Design

The study used a randomized controlled trial design. Assignment to conditions was conducted subsequent to baseline assessment using concealment of allocation procedures defined by protocol and compliant with published recommendations.10 Prior to enrollment a computer-generated randomization scheme was developed. As participants completed baseline assessments, sealed opaque envelopes were used to execute assignments. Participants were randomly assigned to the HIV intervention condition or a health promotion condition using a 2:1 intervention-to-comparison condition allocation ratio. This randomization ratio was selected to provide increased power to detect a secondary biological outcome,11 reduction in human papillomavirus (HPV) incidence. Immediately following randomization participants received their allocated study condition.

Intervention Methods

The HIV intervention consisted of two 4-hour group sessions, facilitated by two trained African-American female health educators, was administered on two consecutive Saturdays at the Kaiser Center where they were recruited, and had an average of 10 participants per session. The health promotion condition also implemented by two trained African-American female health educators consisted of one 4-hour group session that emphasized nutrition education. The HIV intervention was informed by CDC-defined evidence based HIV interventions developed by the study team12 and applied complementary theoretical frameworks to guide program activities. Social Cognitive Theory13 informed HIV intervention content by seeking to enhance participants’ attitudes and skills in abstaining from sexual intercourse, practicing low-risk sexual behaviors (i.e. outercourse), avoiding untreated STIs, using condoms consistently, and refraining from having multiple and concurrent sexual partners. Content regarding avoiding concurrency emphasized valuing one’s body, perceiving one’s body as a temple (a culturally appropriate connotation), informing participants of the heightened risk of STIs, including HIV, when women engage in concurrency, and discussing partner selection strategies that encouraged monogamy (for both the female participant and their male sexual partners).

HIV intervention content was also informed by the Theory of Gender and Power,14 which examines economic forces, power imbalances, gender-related factors, and biological influences affecting women’s HIV risk. Theoretically informed content sought to enhance women’s awareness of power imbalances, such as relationships that threaten their safety, and by teaching women about economic forces which may reduce their self-sufficiency, such as dating male partners who desire pregnancy. The theory informed intervention content by educating participants’ about gender-related HIV prevention strategies, such as, refraining from vaginal douching15 and enhancing sexual communication, and by educating women about biological influences which could reduce HIV risk, such as encouraging participants to have their male sexual partners seek STI testing and treatment if necessary.16 HIV prevention strategies were equally emphasized and the benefits of adopting multiple strategies was discussed.17,18

Data Collection

Data collection occurred at baseline, 6- and 12-months follow-up. At each assessment participants completed a 40-minute Audio Computer-Assisted Survey Interview (ACASI) that collected psychosocial and sexual behavior data. To enhance confidentiality, codes rather than names were used, facilitators did not have access to ACASI data, and to minimize interviewer bias, ACASI monitors were blind to participants’ condition. At each assessment self-administered vaginal swabs were collected and assessed for STIs. STI assays were conducted at the Emory University Pathology Research Laboratory using polymerase chain-reaction nucleic acid amplification assays.

Non-viral STIs

Acquiring an incident non-viral STI was the primary outcome, defined as testing positive for Chlamydia (CT), gonorrhea (GC), or trichomoniasis (TV), at either the 6- or the 12-month assessment. We compared the cumulative percentage of participants in each condition with any of the three STIs from enrollment to the 6- and 12-month assessment, per protocol in other HIV prevention trials.19 One swab was tested for Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC) and Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) using the Becton Dickinson ProbeTec ET Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae Amplified DNA Assay. A second swab was tested for Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) using Taq-Man PCR.20 Women testing STI positive were given single-dose therapy and received counseling per CDC recommendations.

Human papillomavirus

Incident high-risk HPV infection was the secondary biological outcome, defined as a laboratory-confirmed test for HPV type 16 or 18 at the 12-month follow-up assessment after testing HPV-negative at baseline (HPV was not assessed at the 6-month assessment). HPV was selected as an outcome based on its prevalence in women21 and being implicated as a risk factor for HIV.22 Participants provided a self-administered vaginal swab at baseline. Women testing negative for high risk HPV at baseline were re-screened at 12-month assessment. Swabs were tested by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)/reverse blot strip assay.23 Low-risk HPV types were not assessed. Women testing positive for high-risk HPV were referred for follow-up at Kaiser Permanente.

Behavioral outcomes

Concurrency was defined as participants who self-report having a main male sexual partner for 6 months or longer and who also self-report having another male sexual partner during this time period.24 The percent of participants engaging in concurrency and the prevalence of multiple, non-overlapping male sexual partners, in the past 6 months was measured. Other sexual behaviors were assessed for the 30 day period prior to baseline, 6- and 12-month assessment. The frequency of unprotected intercourse acts for vaginal and oral sex was computed separately for each sexual activity by dividing the number of times a condom was not used by the total number of intercourse acts for vaginal sex as well as oral sex. A single item assessed frequency of douching by asking participants the number of times they douched in the past 30 days. A single item assessed frequency of outercourse, defined as number of times participants masturbated a male sexual partner in the past 30 days. Given the projected low HIV incidence over the follow-up, HIV was not considered an outcome.

Mediators

Mediators were derived from the underlying theoretical frameworks and assessed using reliable and valid scales. Responses to scale items were summed and means calculated. The HIV knowledge index was measured using 7-items which had a true/false response format with higher scores indicating greater HIV knowledge. Perceived partner barriers to condom use was measured using a 6-item scale with lower scores indicating participants perceived fewer partner barriers to effectively use condoms (alpha = .88).25 Condom use self-efficacy was measured using a 9-item scale with higher scores indicating participants’ greater confidence in their ability to properly use condoms (alpha = .88).25 Partner communication was assessed by participants indicating the frequency of safer sex discussions with male sex partners. Higher scores indicate greater communication frequency. Partner pregnancy desire was assessed using a five-point scale with higher scores indicating participants perceived their male sex partner as having a strong desire for pregnancy outside of marriage.

Data Analysis

Given enrollment of 848 participants assigned to treatment with a 2:1 randomization allocation ratio, we estimated accruing 568 participants to the intervention and 280 to the comparison. Baseline prevalence was estimated at 17% such that a 25% reduction would correspond to a post-treatment incidence of 12.8%. Following Rochon,26 we assumed a within-participant correlation of 5% and an attrition rate of 20%, yielding approximately 70% power to detect a 25% reduction in STI incidence. Data analysts were blind to study conditions. Analyses were performed only on pre-specified hypotheses using an intention-to-treat protocol in which participants were analyzed in their assigned conditions.27 Differences between conditions were assessed using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square analyses for categorical variables. Variables for which differences between conditions approached (P< 0.15) and which were identified as potential confounders were considered covariates. The effectiveness of the intervention was analyzed over the 12-month period (from baseline to 12 month assessment) using population generalized estimating equations (GEE) for logistic and linear regression models. Statistical models included a time-independent variable (study condition) and time-dependent variables (covariates and outcomes). Models included the corresponding baseline measure of the outcome of interest as well as the theoretically important covariates such as history of forced sex and receipt of public assistance. An indicator for the time period was included in the model to capture any unaccounted temporal effects.28 An indicator for cohort was included in the model to adjust for unaccounted group effects. This yields adjusted odds ratios (OR) which assess intervention effects on dichotomous outcomes, and adjusted mean differences to assess intervention effects on continuous outcomes over the 12-month period. The 95% confidence intervals were computed using two-tailed statistical testing. For fitted models adjusted means were calculated and standard errors were estimated.29

RESULTS

Of the 848 participants randomized, 605 were allocated to the HIV intervention and 243 to the comparison condition. We obtained a 1:2.5 randomization ratio (comparison: intervention) as 50 sibling pairs were randomized together in the intervention. Overall, at baseline the prevalence of Chlamydia, trichomoniasis, gonorrhea was, respectively, 10.4% (n = 88), 3.2% (n = 27); 6.5% (n = 55), and the prevalence of having “any STI” was 17% (n = 144). The prevalence of high risk HPV at baseline was 38.9% (n = 259). No differences between conditions were observed for sociodemographic characteristics, hypothesized psychosocial mediators, and behaviors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparability between study conditions at baseline (NOTE: continues onto second page)

| Characteristic | General Health Condition (n = 243) |

HIV Intervention Condition (n = 605) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 22.15 (3.65) | 21.99 (3.60) | .57 |

| Finished high school, % (n) | 37.0 (90) | 36.5 (221) | .89 |

| Living alone, % (n) | 23.5 (57) | 18.8 (114) | .13 |

| Received public assistance, % (n) | 15.6 (38) | 19.7 (119) | .14 |

| Employed, % (n) | 72.4 (176) | 71.2 (431) | .73 |

| Hours work per week, mean (SD) | 35.16 (12.03) | 33.92 (11.76) | .24 |

| Hourly wage, mean (SD) | 11.98 (5.88) | 11.62 (6.53) | .53 |

| Relationship length | 20.17 (19.32) | 21.54 (19.58) | .4 |

| Frequency marijuana use past 30 days, mean (SD) | 1.56 (5.77) | 2.71 (12.64) | .07 |

| Frequency alcohol use past 30 days, mean (SD) | 2.72 (4.09) | 2.55 (4.26) | .59 |

| History of forced sex, % (n) | 17.7 (43) | 16.0 (97) | .56 |

| HIV/STI prevention knowledge, mean (SD) | 5.34 (1.17) | 5.46 (1.10) | .17 |

| Condom self-efficacy, mean (SD) | 28.21 (5.88) | 28.82 (5.39) | .15 |

| Perceived partner barriers to condom use, mean (SD) | 16.95 (3.73) | 17.05 (3.66) | .73 |

| Partner communication frequency past 30 days, mean (SD) | 7.40 (5.62) | 7.11 (5.45) | .49 |

| Douching frequency past 30 days, mean (SD) | 1.41 (0.71) | 1.44 (0.78) | .69 |

| Sexual behaviors | |||

| Percentage condom use for vaginal sex in past 30 days, mean (SD) | 51.00 (40.00) | 46.00 (39.00) | .13 |

| Condom for oral sex in past 30 days, % (N) | 8.9 (29) | 11.0 (14) | .48 |

| Had multiple sexual partners in past 6 months, % (n) | 39.9 (97) | 35.5 (215) | .23 |

| Had concurrent sexual partners in past 6 months, % (n) | 18.7 (89) | 16.5 (30) | .51 |

| Reported ever having an HIV test, % (n) | 62.4 (93) | 66.3(227) | .4 |

| Frequency of outercourse in past 30 days, mean (SD) | 15.44 (3.53) | 15.67 (3.33) | .39 |

| Frequency of outercourse in past 6 months, mean (SD) | 2.22 (7.30) | 2.25(5.62) | .95 |

| STIs | |||

| Chlamydia, % (N) | 8.6 (21) | 11.1 (67) | .294 |

| Trichomoniasis, % (N) | 8.2 (20) | 5.8 (35) | .191 |

| Gonorrhea, % (N) | 2.5 (6) | 3.5 (21) | .452 |

| Any STDs, % (N) | 18.5 (45) | 16.4 (99) | .450 |

Of the 605 participants allocated to the HIV intervention condition, 441 (72.9%) completed the 6-month assessment and 452 (74.7%) completed the 12-month assessment. Of the 243 participants allocated to the comparison 194 (79.8%) completed the 6-month assessment and 183 (75.3%) completed the 12-month assessment. 727 (86%) participants were retained for at least one follow-up; 511 (84%) participants in the HIV intervention and 216 (89%) in the comparison. No differences were observed between conditions with participants retained and lost to follow-up at the 6-month assessment (27.10% [n = 441] versus 20.20% [n = 194]) or 12-month assessment (25.30% [n = 452] versus 24.7% [n = 183]).

Over the 12-month follow-up, 89 participants (16.2%) were diagnosed with a new non-viral STI; 10 (1.8%) with gonorrhea, 62 (11.2%) with Chlamydia, and 26 (4.7%) with trichomoniasis. At the 12-month follow-up 60 participants (28.0%) were diagnosed with an incident high-risk HPV infection.

In the HIV intervention 96.2% (n = 588) of participants completed both sessions. All (n = 244) participants in the comparison condition completed the single session. Participants’ ratings of their satisfaction with session implementation and content, assessed on a 5-point Likert scale, indicated high ratings for the intervention (mean = 4.8; sd =.23) and comparison (mean = 4.6; sd = .24; P = 0.89).

Effects of the HIV Intervention

For the primary biological outcome, at the 6-month assessment, 19 participants (9.7%) in the comparison condition and 27 participants (6.1%) in the HIV intervention condition developed a non-viral STI (OR=0.52; 95% CI=0.26-1.04) (Table 2). At 12-month assessment 22 participants (12.0%) in the comparison and 42 participants (9.5%) in the HIV intervention developed an STI (OR=0.67; 95% CI=0.37-1.20). In GEE analyses across the 12-month study period, relative to the comparison, 38% fewer participants in the intervention developed non-viral STIs (OR= 0.62; 95% CI=0.40-0.96).

Table 2.

Effects of the intervention on incidence of any non-viral STI (CT, GC, TV) over the 12-month follow-up

| 6-Month Assessment | 12-Month Assessment | GEE Model Baseline – 12-Month |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Percent | Unadjusted Percent | |||||||

| I | C | I | C | |||||

| [N = 441] | [N=194] ORa | (95%CI) | [N= 452] | [N = 183] OR | (95% CI) b | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| % | % | % | % | |||||

| (n) | (n) | (n) | (n) | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Non-viral STIs (CT, GC, TV) |

6.1% (27) |

9.7% (19) |

0 .52 (0.26, 1.04) | 9.5% (42) |

12,0% (22) |

0 .67 (.37, 1.20) | 0.62 (0.40, 0.96) | .033 |

For to the secondary biological outcome, incident high-risk HPV infection, at the 12-month assessment 24 participants (39.3%) in the comparison condition and 36 participants (23.5%) in the HIV intervention condition had a high-risk HPV infection (OR= 0.60; 95% CI= 0.39-0.91) (Table 3). At 12-months follow-up the unadjusted incidence rate for high-risk HPV was 0.39 in the comparison condition and 0.24 in the intervention condition (rate ratio=0.62; 95% CI=0.35– 1.05). In adjusted analyses, relative to the comparison condition, about 63% fewer participants in the HIV intervention condition developed high-risk HPV infection (OR=0.37; 95% CI= 0.18-0.77).

Table 3.

Effects of the intervention on HPV incidence at 12-months follow-up

| Crude HPV incidence: At 12 months follow-up |

Baseline – 12 months | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Percent I [N=153] % (n) |

Unadjusted Percent C [N=61] % (n) |

Relative Risk Ratio |

(95% CI) | P-value | Odds Ratioa |

(95% CI)b | P-value |

|

| |||||||

| 23.5% (36) |

39.3% (24) |

0.60 | (0.39, 0.91) | .02 | 0.37 | (0.18, 0.77) | 0.008 |

For the behavioral outcomes, across the 12-month study period, participants in the HIV intervention condition, relative to the comparison condition, were less likely to have a concurrent male sex partner (OR=0.55; 95% CI=0.37-0.83) (Table 4); more likely to communicate their STI test results with their main male sexual partner (OR=1.52; 95% CI=1.11-2.06), more likely to report that their main male sexual partner was treated for STIs (OR=1.41; 95% CI=1.05-1.90), more likely to use condoms during oral sex (OR=2.05; 95% CI=1.01–4.14), and masturbate their main male partner more frequently in the past 3 months (1.48 vs. 1.05; % Mean Difference = 0.43; 95% CI=0.03 – .83) as well as over the past 30 days (0.76 vs. 0.55; % Mean Difference = 0.21; 95% CI= 0.002 - 0.42). Across the 12-month follow-up period, participants in the HIV intervention, relative to the comparison, were less likely to have a male sexual partner with a strong desire to have children (OR=0.62; 95% CI=0.40-0.95), less likely to have multiple male sexual partners (OR=0.73; 95% CI=0.54-0.99), and less likely to report douching (OR=0.38; 95% CI=0.23-0.62). Across the 12-month study period, participants in the HIV intervention condition, relative to the comparison condition, had higher mean scores on HIV knowledge, condom use self-efficacy, and perceived fewer partner barriers to practicing safer sex (Table 5). The total number of safer sex activities employed by each woman was assessed by summing if participants had outercourse, used condoms consistently, did not engage in concurrency, used condoms for oral sex, or reduced having multiple sexual partners. Compared to the comparison, participants in the HIV intervention used more safe sex strategies at the 6-month (3.21 vs. 2.92; % Mean Difference = .30; 95%CI=.12-.49; P = .002) and 12-month (3.23 vs. 3.04; % Mean Difference = .19; 95%CI = .01-.39; P = .048) follow-up as well as over the 12-month period (3.22 vs. 2.98; Relative Difference = 8.61; 95%CI=4.38-12.84; P = .001).

Table 4.

Effects of the intervention on categorical measures of HIV/STD-sexual behavior

| Baseline | 6-Month Assessment | 12-Month Assessment | GEE Model Baseline – 12-Month |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Percent | Unadjusted Percent | Unadjusted Percent | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| I | C | I | C | I | C | ||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| [N=605] | [N=243] | P | [N = 441] | [N=194] ORa | (95%CI) b | [N= 452] | [N = 183] OR | (95% CI) b | OR (95% CI) | P | |

|

| |||||||||||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | ||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| (n) | (n) | (n) | (n) | (n) | (n) | ||||||

| Ever used condoms during oral sex (past 30 days |

11.0% (14) |

8.9% (29) |

.48 | 19.9% (44) |

8.1% (8) |

2.09 (0.86, 5.12) | 18.7% (43) |

14.3% (14) |

1.63 (.70, 3.77) | 2.05 (1.01, 4.14) | .047 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Reported multiple non overlapping sexual partners (past 6 months) |

35.5% (215) |

39.9% (97) |

.23 | 26.3% (182) |

34.0% (66) |

0.65 (0.44, 0.96) | 24.6% (111) |

28.4% (52) |

0.78 (.52, 1.18) | 0.73 (.54, .99) | .045 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Had a concurrent partner (past 6 months) |

16.5% (30) |

18.7% (89) |

.51 | 13.7% (57) |

20.0% (36) |

0.40 (0.23, 0.69) | 15.0% (68) |

17.5% (32) |

0.70 (.41, 1.21) | 0.55 (0.37, 0.83) | .005 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Reported main partner was treated for an STI |

na | na | 30.3% (111) |

25.0% (42) |

1.21 (0.89, 1.64) | 33.1% (139) |

26.5% (45) |

1.25 (0.94,1.66 | 1.41 (1.05, 1.90) | .021 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Reported not douching |

42.1% (255) |

35.4% (86) |

.07 | 49.0% (44) |

36.6% (71) |

0.37 (0.20, 0.68) | 50.2% (227) |

35.0% (64) |

0.38 (.22, .67) | 0.38 (0.23, 0.62) | .0001 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Selected male partner who immediately desired children |

14.5% (88) |

17.3% (22) |

.32 | 11.1% (49) |

17.0% (33) |

0.60 (0.36, 1.0) | 6.2% (28) |

9.8% (18) |

0.68 (.35, 1.31) | 0.62 (0.40, 0.95) | .030 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Informed main partner of STI test results |

na | na | 71.8% (288) |

62.9% (110) |

1.14 (1.00, 1.30) | 76.3% (345) |

68.3% (125) |

1.12 (1.0, 1.25) | 1.52 (1.11, 2.06) | .008 | |

Table 5.

Effects of the intervention on continuous measures of HIV/STD sexual behavior

| 6-Month Assessment | 12-Month Assessment | GEE Model Baseline – 12-Month |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Baseline | Unadjusted Means | Mean Difference (D)a |

(95% CI) | Unadjusted Means | Mean Difference (D)a |

(95% CI) | Adjusted Means |

(95%CI) | ||||

| I C (sd) (sd) P |

I (sd) |

C (sd) |

I (sd) |

C (sd) |

I | C | P | |||||

| HIV/STI prevention knowledge |

5.46 5.34 (1.10) (1.17) .17 |

6.29 (0.93) |

5.70 (1.08) |

0.36 | ( 0 .16, 0.57) | 6.39 (0.87) |

5.74 (1.10) |

0.42 | (.21, .63) | 6.34 | 5.72 | (5.46,10.23) .0001 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Condom use self- efficacy |

28.82 28.21 (5.39) (5.88) .15 |

30.83 (4.39) |

29.11 (5.34) |

0.31 | (−.86, 1.47) | 16.76 (3.68) |

17.21 (3.70) |

−.04 | (−1.15, 1.06) | 30.90 | 29.30 | (0.98, 3.21) .0001 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Perceived partner barriers to condom use |

17.05 16.95 (3.66) (3.73) .73 |

16.76 (3.68) |

17.21 (3.70) |

−1.02 | (−2.03, −.8) | 17.18 (3.48) |

17.41 (3.70) |

−1.19 | (−1.96,−.43) | 16.97 | 17.31 | (5.49, 12.42) .038 |

DISCUSSION

This is the first trial to demonstrate that a two-session HIV intervention can achieve reductions in non-viral STI incidence, high-risk HPV incidence, and individual concurrency. Participants in the intervention were 45% less likely to have had a concurrent partner. Participants in the intervention were also 38% less likely to have a non-viral STI and 63% less likely to have high-risk HPV. To contextualize these biological findings, a meta-analysis performed by the CDC (2009)30 involving 17 HIV/STI behavioral interventions conducted among African American females observed a 19% reduced odds of having any STI among intervention participants relative to comparison participants. The results observed in the current study are more robust that the average intervention effect reported in the meta-analysis.

Compared to women in the comparison, women in the HIV intervention used more safer sex strategies. Perhaps as a result of adopting a number of other risk-reduction strategies women did not enhance condom use during vaginal sex. Of particular importance, the HIV intervention demonstrated the capacity to reduce multiple sexual partners and sexual concurrency. Even small changes in concurrency may have a marked impact on transmission of HIV among African Americans.4 Concurrency by women does not protect women; their risk is derived from the concurrent relationships of their male sexual partners.5 However, research has demonstrated that women who engage in concurrency often have male sexual partners who also engage in concurrency.31 HIV interventions that motivate women to reduce concurrency may affect women’s selection of a male sexual partner. As individuals often choose partners like themselves, women who reduce concurrent partners may be more inclined to select male partners who are less likely to engage in concurrency, 32 which may reduce women’s HIV risk.

As male pregnancy desire can have an adverse economic impact on women and increase their HIV risk,33 the HIV intervention addressed partner selection skills to enhance the likelihood of women selecting male sexual partners who did not desire childbearing outside of marriage. Reductions in incident STIs may have also been achieved as women were informed of biological influences impacting women’s HIV risk. As part of this study, none of the participant’s male sex partners received STI treatment. However, HIV intervention participants were encouraged to communicate the importance of STI testing and treatment to male partners. HIV intervention participants reported that their male sexual partners were more likely to seek STI testing and treatment. Furthermore, participants in the HIV intervention were less likely to engage in gendered factors influencing HIV risk, such as vaginal douching. Enhancing partner STI testing/treatment and reducing vaginal douching are both associated with lower STI acquisition.15,16 Thus, the effects of the HIV intervention, which targeted Southern African American women’s HIV risks, may be attributable to providing a range of prevention strategies that address behavioral, economic, gender, and biological factors influencing their HIV vulnerability.

Study strengths include selecting a random sample, biological outcomes, large sample size and, a randomized controlled design. This study may not be generalizable to women who are not African American, who have a different risk profile (drug users), who engage in concurrency defined differently than in this study, or who are not HMO members. While the comparison was not time matched to the intervention, the provision of STI testing and counseling with minimal health education was delivered to represent the usual STI services participants may receive at a clinic. Siblings were not randomized to avoid contamination; they were assigned as a pair to the intervention which may introduce bias.

Conclusion

Globally, very few published HIV interventions address concurrency reduction. Noteworthy is the Ugandan HIV control approach that communicated a risk avoidance message of being “faithful to one’s partner” or Zero Grazing and witnessed population-level reductions in HIV incidence.34 Southern African American women are disproportionately affected by HIV, future interventions for this population and other women should focus on concurrency, address structural factors and women-controlled biomedical strategies.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH62717, MH8428905), the National Institute of Drug Abuse (DA8429360) with additional support provided by the Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30 A1050409).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None reported.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.HIV/AIDS . CDC Fact Sheet. CDC; Atlanta, GA: 2008. Among Women Fact Sheet. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(5):520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campsmith M, et al., editors. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2006. 39 ed Volume 18. US Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Doherty IA. HIV and African Americans in the southern United States: sexual networks and social content. Sex Trans Dis. 2006;33(7 Suppl):S39–S45. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000228298.07826.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gresenguet G, Kreiss JK, Chapko MK, Hillier SL, Weiss NS. HIV infection and vaginal douching in central Africa. AIDS. 1997;11(1):101–6. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199701000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abma JC, Chandra A, Mosher WD, et al. Fertility, family planning and women’s health: new data from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Vital Health Stat. 1997:1–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson F, Donaldson KH, Stancil TR, Fullilove RE. Concurrent sexual partnerships among African Americans in the rural South. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14(3):155–160. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodder S, Justman J, Haley DF, et al. Challenges of a hidden epidemic: HIV prevention among women in the United States. AIDS. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fbbdf9. in Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khoury MJ, Gwinn M, Ioannidis JPA. The emergence of translational epidemiology: From scientific discovery to population health impact. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(5):517–524. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulz KF. Subverting randomization in controlled trials. JAMA. 1995;274:1456–1458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dumville JC, Hahn S, Miles JNV, Torgerson DJ. The use of unequal randomization ratios in clinical trials: A review. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2006;27:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Enhancing adoption of evidence-based HIV interventions: Promotion of a suite of HIV prevention interventions for African American women. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(Supplement A):161–170. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory and exercise of control over HIV infection. In: DiClemente RJ, Peterson J, editors. Preventing AIDS: Theories and Methods of Behavioral Interventions. Plenum Publishing Corp; New York, NY: 1994. pp. 25–59. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV related exposures, risk factors and effective interventions for women. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27:539–565. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McClelland SR, Richardson BA, Hassan WM, Chohan V, Lavreys L, Mandaliya K, Kiarie J, Jaoko W, Ndinya-Achola OJ, Baeten JM, Kurth AE, Holmes KK. Improvement in vaginal health for Kenya women at risk for acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: Results of a randomized trial. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2008;197:1361–1368. doi: 10.1086/587490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grosskurth H, Mosha F, Todd J. Impact of improved treatment of sexually transmitted diseases on HIV infection in rural Tanzania: randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 1995;346:530–536. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coates TJ, Richter L, Caceres C. Behavioural strategies to reduce HIV transmission: how to make them work better. The Lancet. 2008;372(9639):669–684. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60886-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shain RN, Perdue ST, Piper JM, Holden AEC, Champion J, Newton ER, Korte JE. Behaviors Changed by Intervention Are Associated With Reduced STD Recurrence: The Importance of Context in Measurement. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29(9):520–529. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200209000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, Rhodes F, Rogers J, Bolan G, Zenilman J, Hoxworth T, Malotte K, Iatesta M, Kent C, Lentz A, Graziano S, Beyers RH, Peterman TA, for the Project RESPECT Study Group Efficacy of Risk-Reduction Counseling to Prevent Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Sexually Transmitted Diseases: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1161–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.13.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caliendo AM, Jordan JA, Green AM, Ingersoll J, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Real-time PCR provides improved detection of Trichomonas vaginalis infectioncompared to culture using self-collected vaginal swabs. Infectious Diseases inObstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;13:145–150. doi: 10.1080/10647440500068248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stone KM, Karem KL, Sternber MR, et al. Seroprevalence of Human Papillomavirus Type 16 Infection in the United States. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2002;186:1396–1402. doi: 10.1086/344354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Auvert B, Lissouba P, Cutler E, Zarca K, Puren A, Taljaard D. Association of oncogenic and nonocogenic human papillomavirus with HIV incidence. JAIDS. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b327e7. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gravitt PE, Peyton CL, Apple RJ, Wheeler CM. Genotyping of 27 human papillomavirus types by sing L1 consensus PCR products by a single hybridization, reverse line blot detection method. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3020–3027. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.3020-3027.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorbach PM, Stoner BP, Aral SO, Whitting WL, Holmes KK. “It takes a village”: Understanding concurrent sexual partnerships in Seattle, Washington. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29(8):453–462. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200208000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF, et al. Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for African American adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:171–179. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rochon J. Application of GEE procedures for sample size calculations in repeated measures experiments. Statistics in Medicine. 1998;17:1643–1658. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980730)17:14<1643::aid-sim869>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piantadosi S. Clinical Trials: A Methodologic Perspective. John Wiley & Sons; New York, NY: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Efron B. Nonparametric estimates of standard error: the jackknife, the bootstrap, and other methods. Biometrika. 1981;68:589–599. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hardin JW, Hilbe JM. Generalized Estimating Equations. Chapman & Hall/CRC; New York, NY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crepaz N, Marshall KJ, Aupont LW, Jacobs EW, Mizuno Y, Kay LS, Jones P, Hubbard McCree E, O’Leary A. The efficacy of HIV/STI behavioral interventions for African American Females in the United States: A Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:2069–2078. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.139519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doherty IA, Schoenbach VJ, Adimora A. Sexual mixing patterns and heterosexual HIV transmission among African Americans in the Southeastern United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52:114–120. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ab5e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mah TL. Prevalence and correlates of concurrent sexual partnerships among young people in South Africa. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2010;37(2):105–108. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181bcdf75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davies S, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Crosby R, Harrington K. Psychosocial correlates of desire for pregnancy among African American females. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2002;27(1):55–62. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stoneburner RL, Low-Beer D. Population-level HIV declines and behavioral risk avoidance in Uganda. Science. 304(5671):714–718. doi: 10.1126/science.1093166. 204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]