Abstract

We wanted to assess oral and salivary changes in end stage renal disease (ESRD) patients undergoing hemodialysis (HD) and to understand the correlation of such changes with renal insufficiency. The cross-sectional study was performed among 100 ESRD patients undergoing HD. Among these, 25 patients were randomly selected to assess the salivary changes and compared with 25 apparently healthy individuals who formed the control group. Total duration of the study was 15 months. Oral malodor, dry mouth, taste change, increased caries incidence, calculus formation, and gingival bleeding were the common oral manifestations. The flow rates of both unstimulated as well as stimulated whole saliva were decreased in the study group. The pH and buffer capacity of unstimulated whole saliva was increased in the study group, but stimulated whole saliva did not show any difference. ESRD patients undergoing HD require special considerations during dental treatment because of the various conditions inherent to the disease, their multiple oral manifestations and the treatment side-effects.

Keywords: Hemodialysis, oral manifestations, renal diseases, salivary changes

Introduction

The incidence of renal diseases continues to rise worldwide and as a consequence, increasing number of renal patients will probably require oral healthcare. The oral clinicians need to understand the multiple organ systems that can be affected, the compromised renal clearance, and the adverse side-effects of multiple drugs therapy usually prescribed to these patients.[1] Hence, the present study was performed to assess oral and salivary changes (flow rate, pH, and buffer capacity) in end stage renal disease (ESRD) patients undergoing hemodialysis (HD).

Materials and Methods

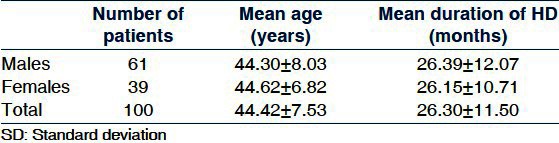

A total of 100 patients with ESRD on HD in M S Ramaiah Group of Hospitals, Bangalore formed the study group [Table 1]. Patients with early stages of kidney diseases not requiring HD and patients with kidney transplantation were not included. Among the 100 study subjects, 25 were randomly selected to assess the salivary changes. Twenty-five healthy individuals without history of any serious illness and who were not under any medication known to affect salivary flow rate formed the control group for salivary changes.

Table 1.

Demographic data of the study group included for oral examination

Oral examination

The clinical examination was carried out by the method suggested by Kerr et al.,[2] Oral hygiene index simplified was used to assess the clinical levels of debris and calculus, decayed missing filled tooth index (DMFT Index) for prevalence of dental caries, and Periodontal disease index for gingival and periodontal status.

Salivary collection

Salivary samples were collected from the study group and the control group after obtaining the informed consent and the various salivary variables were analyzed.

Salivary flow rate

Samples from patients (a day after dialysis visit) and control group were collected between 8:00 AM and 11:00 AM to minimize effects of the diurnal variability in salivary composition. Samples were collected before meals or at least 2 h after meals. During the time of collection, smoking, eating and talking were prohibited. Unstimulated whole saliva was collected for 10 min by spitting method. Stimulated whole saliva was collected for 5 min from each subject with the aid of standard weight Paraffin-Wax chewing method. The collection was timed, so that flow rate (mL/min) could be measured.[3]

Salivary pH

Following saliva collection, pH was measured immediately using the narrow range pH strip system (Merck). One drop of the collected saliva (unstimulated and stimulated) was placed on the test strip and its color change reflected the pH of saliva.

Salivary buffer capacity

Salivary buffer capacity was measured according to the standard method of Ericsson.[4] The final pH of the solution was assessed in the way similar to determine salivary pH and taken as an expression of the buffer capacity of the salivary samples.

Statistics

Continuous variables such as age, flow rate, pH, and buffer capacity were analyzed using mean and standard deviation. Independent Students’ t test was used to compare mean values of the salivary parameters between the study and the control group. Level of significance was fixed at 0.5%.

Results

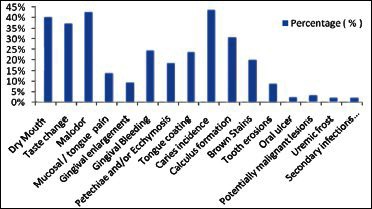

Sixty-five (65%) of the 100 study subjects showed at least one oral manifestation. Oral malodor, dry mouth, and taste change were the common subjective symptoms. Increased caries incidence, calculus formation, and gingival bleeding were common objective signs [Graph 1].

Graph 1.

Oral manifestations among the study group

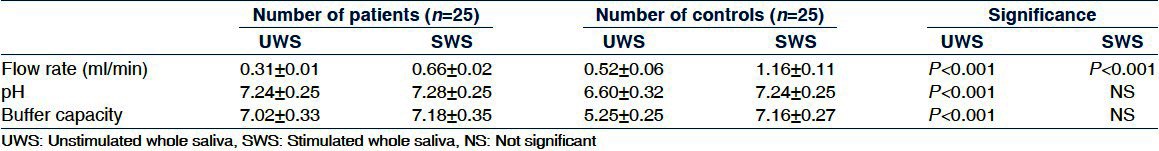

The mean flow rate of unstimulated and stimulated whole saliva was significantly lower in the ESRD patients compared to the controls. The pH and buffer capacity of the unstimulated whole saliva in ESRD patients was significantly higher than the controls. The pH and buffer capacity of the stimulated whole saliva of ESRD patients did not show any significant differences compared to the controls [Table 2].

Table 2.

Changes in unstimulated and stimulated whole saliva from the study and control group

Discussion

Uremic fetor, an ammoniacal odor typical of uremic patients is caused by high concentration of urea in the saliva which is broken down to ammonia by urease.[5,6] in addition, oral malodor can also result from neglected oral health due to the chronic nature of the illness.

Dry mouth (xerostomia) can be observed in renal patients due to restriction in fluid intake, the side effects of drugs (fundamentally antihypertensive agents), possible salivary gland alteration and oral breathing secondary to lung perfusion problems.[7] The significantly reduced mean flow rate of unstimulated as well as stimulated whole saliva in ESRD patients can be a contributory factor to xerostomia.

ESRD can give rise to altered taste sensation, and some patients may complain of an unpleasant and metallic taste. High levels of urea and dimethyl and trimethyl amines, and low level of zinc might be associated with decreased taste perception in uremic patients.[3] These taste disturbances could also be caused by metabolic disturbances, the use of medication, a diminished number of taste buds, and changes in salivary flow rate and composition. Sour and sweet tastes can be more seriously affected than bitter and salty tastes.[8]

Reduced caries prevalence has been reported in ESRD patients. This is attributed to the protective effect of metabolism of urea in saliva, which inhibits bacterial growth and neutralizes bacterial plaque acids.[9,10] In the current study, DMFT index has revealed an increased prevalence of caries which can be correlated to poor oral hygiene, diminished saliva production, and an increase in the number of cariogenic Streptococcus mutans.[11]

Gingival enlargement secondary to drug treatment is one of the most widely documented oral manifestations in patients with renal failure. Such enlargement can be induced by cyclosporine, which is used as immunosuppressant in transplant patients, and/or calcium channel blockers (nifedipine, amlodipine, diltiazem, verapamil) used in pre-dialyzed and dialyzed patients for management of hypertension.[7,12] The condition in turn is aggravated by the deficient oral hygiene [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Gingival enlargement following cyclosporine therapy

A great majority of ESRD patients present with dental calculus possibly due to high salivary urea and phosphate levels. Other important risk factors for the development of dental calculus and dark brown staining of teeth are the ingestion of large quantities of calcium carbonate (used as a phosphate binder to maintain phosphorus homeostasis), extrinsic staining secondary to liquid ferrous sulfate therapy given for the management of anemia and deficient oral hygiene.[6,13,14] Diminished cleansing action due to reduced salivary production can also lead to greater incidence of calculus formation [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Calculus formation and dark brown staining of teeth

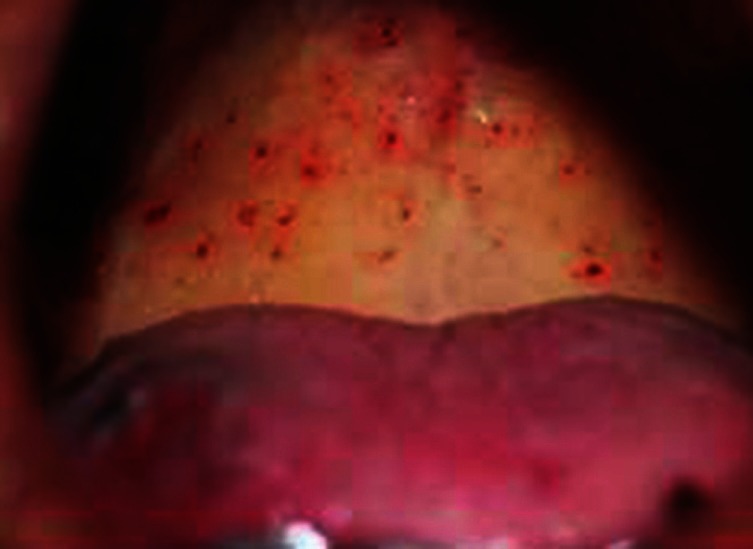

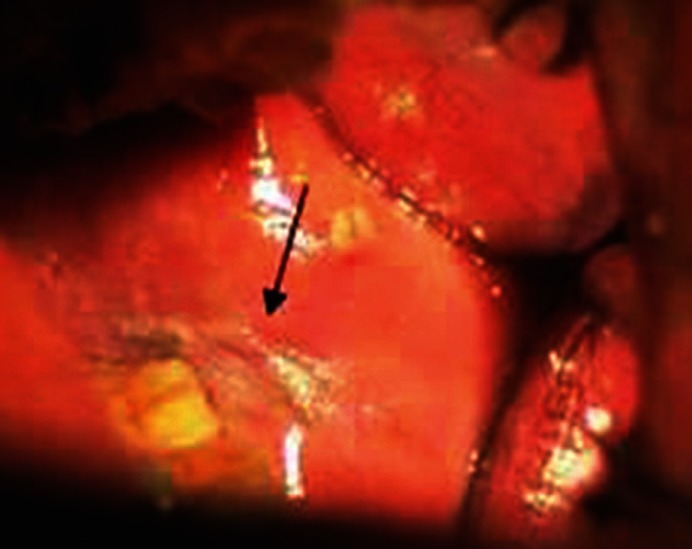

Gingival bleeding, petechiae, and/or ecchymosis can result from platelet dysfunction and the effects of anticoagulants like heparin used to maintain the patency of AV fistulae required for regular vascular access. Uremic toxins and anemia can also play a role [Figure 3].[3,15]

Figure 3.

Petechiae present at hard and soft palate

The accumulation of ammonia might irritate the oral mucosa, resulting in mucosal inflammation. A decrease in the salivary mucin coating over the oral mucosa makes it vulnerable to infections, inflammation, and tissue damage leading to tongue and mucosal pain.[3,16]

Uremic frost, an uncommon clinical observation associated to azotemia and uremia may occasionally be present in the renal patients. Uremic frost is a condition when urea and urea derivatives are secreted through the saliva in oral cavity and sweat in skin, which evaporates away and may leave solid uric compounds, resembling a frost [Figure 4].[16,17]

Figure 4.

Uremic frost involving left buccal mucosa

Candidiasis and increased vulnerability to human herpes virus 8 is common among hemodialyzed as well as transplant patients due to longer durations of immunosuppression.[1,18,19] Due to diminished salivary flow, the salivary defense can be compromised in these patients, and a shift in the composition of the oral microflora can occur toward more virulent gram-negative species [Figure 5]. Mucosal lesions, particularly white lesions have been reported in ESRD patients. Common observations are drug induced lichenoid lesions, an increased susceptibility to epithelial dysplasia and carcinoma of the lip. The increased risk of malignization in ESRD patients probably reflects the effects of iatrogenic immune suppression [Figure 6].[1,17,18]

Figure 5.

Psuedomembranous candidiasis affecting tongue

Figure 6.

Homogenous leukolplakia involving left buccal mucosa (Smoking related)

The lower flow rates of both unstimulated and stimulated whole saliva can be attributed to direct uremic involvement of the salivary glands leading to decreased parenchymatous and excretory functions, and as a result of dehydration due to restriction in fluid intake. Acute stress levels in these patients may also possibly reduce the salivary flow rate.[3,19]

The higher pH of unstimulated whole saliva in ESRD patients can be contributed to a higher concentration of ammonia in saliva due to the hydrolysis of urea by the enzyme urease.[20] pH of stimulated whole saliva does not reveal any significant difference because sodium and bicarbonate concentrations increase with increased flow rates, resulting in a higher salivary pH. This effect might mask the changes that are due to the disease condition.[21]

The higher buffer capacity of unstimulated whole saliva in ESRD patients can be correlated to the elevated salivary phosphate concentration.[3,20] No significant difference is observed in buffer capacity of stimulated whole saliva as stimulation itself increases concentration of bicarbonates in parotid saliva, leading to a higher buffer capacity.[21,22]

Conclusion

ESRD patients undergoing HD show apparent oral and salivary changes. These patients require special considerations in relation to dental treatment, not only because of the conditions inherent to the disease and its multiple oral manifestations, but also because of the side-effects and characteristics of the treatments they receive. The untreated dental infection in immunosuppressed renal patients can potentially contribute to morbidity and future transplant rejection. Thus, there is a need for detailed assessment and provision of good oral care following the diagnosis of ESRD.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Proctor R, Kumar N, Stein A, Moles D, Porter S. Oral and dental aspects of chronic renal failure. J Dent Res. 2005;84:199–208. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerr DA, Ash MM, Millard HD. 6th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1983. The clinical examination in oral diagnosis; pp. 77–240. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kho HS, Lee SW, Chung SC, Kim YK. Oral manifestations and salivary flow rate, pH, and buffer capacity in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing hemodialysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88:316–9. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ericsson Y. Clinical investigations of the salivary buffering action. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. 1959;17:131–65. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wysocki GP, Daley TD. A case of primary oxaluria. J Oral Surg. 1982;4:65–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klassen JT, Krasko BM. The dental health status of dialysis patients. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:34–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de la Rosa-García E, Mondragón-Padilla A, Irigoyen-Camacho ME, Bustamante-Ramírez MA. Oral lesions in a group of kidney transplant patients. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2005;10:196–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burge JC, Schemmel RA, Park HS, Greene JA., 3rd Taste acuity and zinc status in chronic renal disease. J Am Diet Assoc. 1984;84:1203–6. 1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy HM. Dental considerations for the patient receiving dialysis for renal failure. Spec Care Dentist. 1988;8:34–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1988.tb00682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Nowaiser A, Roberts GJ, Trompeter RS, Wilson M, Lucas VS. Oral health in children with chronic renal failure. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18:39–45. doi: 10.1007/s00467-002-0999-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Löcsey L, Alberth M, Mauks G. Dental management of chronic haemodialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 1986;18:211–3. doi: 10.1007/BF02082610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciavarella D, Guiglia R, Campisi G, Di Cosola M, Di Liberto C, Sabatucci A, et al. Update on gingival overgrowth by cyclosporine A in renal transplants. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007;12:E19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atassi F. Oral home care and the reasons for seeking dental care by individuals on renal dialysis. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2002;15:31–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epstein SR, Mandel I, Scopp IW. Salivary composition and calculus formation in patients undergoing hemodialysis. J Periodontol. 1980;51:336–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1980.51.6.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Opatry K. Hemostasis disorders in chronic renal failure. Kidney Int. 1997;52:87–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaspers MT. Unusual oral lesions in a uremic patient.Review of the literature and report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1975;39:934–44. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(75)90114-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gudapati A, Ahmed P, Rada R. Dental management of patients with renal failure. Gen Dent. 2002;50:508–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King GN, Healy CM, Glover MT, Kwan JT, Williams DM, Leigh IM, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with leukoplakia, hairy leukoplakia, erythematous candidiasis, and gingival hyperplasia in renal transplant recipients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;78:718–26. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(94)90086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gavaldá C, Bagán J, Scully C, Silvestre F, Milián M, Jiménez Y. Renal hemodialysis patients: Oral, salivary, dental and periodontal findings in 105 adult cases. Oral Dis. 1999;5:299–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1999.tb00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamid MJ, Dummer CD, Pinto LS. Systemic conditions, oral findings and dental management of chronic renal failure patients: General considerations and case report. Braz Dent J. 2006;17:166–70. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402006000200016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engelen L, van den Keybus PA, de Wijk RA, Veerman EC, Amerongen AV, Bosman F, et al. The effect of saliva composition on texture perception of semi-solids. Arch Oral Biol. 2007;52:518–25. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amerongen AV, Veerman EC. Saliva–The defender of the oral cavity. Oral Dis. 2002;8:12–22. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2002.1o816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]