Abstract

Perioperative anaesthetic management of the VentrAssist™ left ventricular assist device (LVAD) is a challenge for anaesthesiologists because patients presenting for this operation have long-standing cardiac failure and often have associated hepatic and renal impairment, which may significantly alter the pharmacokinetics of administered drugs and render the patients coagulopathic. The VentrAssist is implanted by midline sternotomy. A brief period of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) for apical cannulation of left ventricle is needed. The centrifugal pump, which produces non-pulsatile, continuous flow, is positioned in the left sub-diaphragmatic pocket. This LVAD is preload dependent and afterload sensitive. Transoesophageal echocardiography is an essential tool to rule out contraindications and to ensure proper inflow cannula position, and following the implantation of LVAD, to ensure right ventricular (RV) function. The anaesthesiologist should be prepared to manage cardiac decompensation and acute desaturation before initiation of CPB, as well as RV failure and severe coagulopathic bleeding after CPB. Three patients had undergone implantation of VentrAssist in our hospital. This pump provides flow of 5 l/min depending on preload, afterload and pump speed. All the patients were discharged after an average of 30 days. There was no perioperative mortality.

Keywords: Cardiac failure, left ventricular assist device, VentrAssist™

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of chronic heart failure (CHF) and the shortage of donor hearts have led to the development of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) for both bridge to transplant (BTT) and destination therapy (DT).[1,2] Because cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) is required for implantation of these devices, anaesthetising these critically compromised patients requires extensive monitoring, skillful anaesthetic management and expert postoperative care.[3]

CASE REPORT

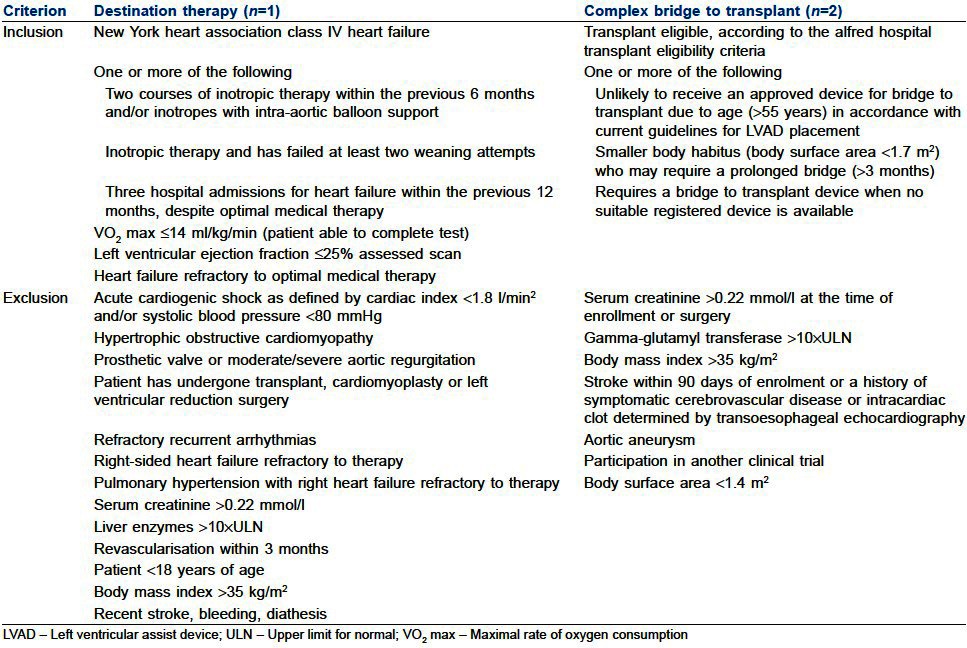

In the present article about our experience with implantation of VentrAssist™ LVAD, three adult patients with end-stage CHF who met pre-specified eligibility criteria [Table 1] were able to participate LVAD implantation programme initiated in 2008. After obtaining approval from institutional review board and written informed consent from the patients, VentrAssist LVAD implantation procedure was performed in these patients. In the first patient, VentrAssist LVAD implantation was performed as DT since he was elderly and non-transplantable. In the second and third patients, VentrAssist LVAD implantation was performed as BTT.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria[4]

Diagnosis of the patients was as follows:

Patient 1: Status post coronary artery bypass grafting, ejection fraction 15%, congestive cardiac failure and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class IV, renal and hepatic dysfunction

Patient 2: Idiopathic cardiomyopathy, ejection fraction 20% and NYHA class IV

Patient 3: Ischaemic cardiomyopathy, status post percutaneous coronary angioplasty (PTCA) and stenting to left anterior descending artery, ejection fraction 15% and NYHA class IV

On the day prior to the surgery, under aseptic precaution, a large bore peripheral cannula (14 G), radial artery cannula (20 G), triple lumen central venous cannula (7 F, 15 cm) and intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) were inserted under local anaesthesia for patients 1 and 2. Third patient was on IABP and milrinone 0.5 μg/kg/min since 5 days preoperatively. Prophylactic antibiotics consisting of cefepime 2 g intravenous (IV) BD, moxifloxacin 400 mg IV BD and fluconazole 200 mg IV BD were administered before the surgery. Anaesthesia was induced with fentanyl 4-5 μg/kg IV and midazolam 0.1 mg/kg IV, and the tracheal intubation was achieved with pancuronium 0.1 mg/kg IV. Volume-controlled ventilation was started with a 10 ml/kg tidal volume. Anaesthesia was maintained with inhalational mixture of O2+ air (50:50), isoflurane (1%) and fentanyl 5 μg/kg IV intermittently. In addition to routine monitoring, continuous cardiac output was being measured by thermodilution technique via the Swan Ganz continuous cardiac output catheter and Vigilance monitor (both by Edwards Lifesciences Corp., Irvine, CA, USA). Measurement of activated clotting time (ACT), thromboelastography (TEG) and transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) were performed when required. Temperature of the patient was maintained using warming blanket and fluid warmer. Methyl prednisolone 30 mg/kg IV was given to reduce systemic inflammatory response. To minimise blood loss in perioperative period, ε-aminocaproic acid total of 15 g in divided doses was given IV before, during and after CPB.

Operative procedure

The heart and ascending aorta were approached through a mid-line sternotomy. A small pocket in the left sub-diaphragm region was created to house the device. Heparin 400 units/kg was administered to achieve an ACT >400 s. The ascending aorta and right atrium were cannulated for CPB. The IABP was stopped and CPB was initiated. With the heart beating, the apex of the left ventricle was cored using a core device, and the inflow cannula was inserted and secured. The end of the outflow cannula was anastomosed to ascending aorta.

During CPB period, the mean arterial pressure (above 60-70 mmHg), sinus rhythm, heart rate (around 80/min), core temperature (34°C to 37°C) and steep Trendelenberg position were maintained. The de-airing of the pump and chambers of the heart was performed. Finally, the patients were gradually weaned from CPB. When the CPB flow was 1 l/min, the pump was started at a minimum speed of 1800 rpm. The pump speed was increased by 1000 rpm increments throughout the entire operating range until aortic valve opening could be verified with TOE and observed on the arterial pressure wave form. If the pump speed was too fast, the arterial pressure wave form decreased and the dicrotic notch was absent (indicating a closed aortic valve). The presence of a pulsatile wave form with a dicrotic notch indicated some aortic outflow and was verified with TOE.

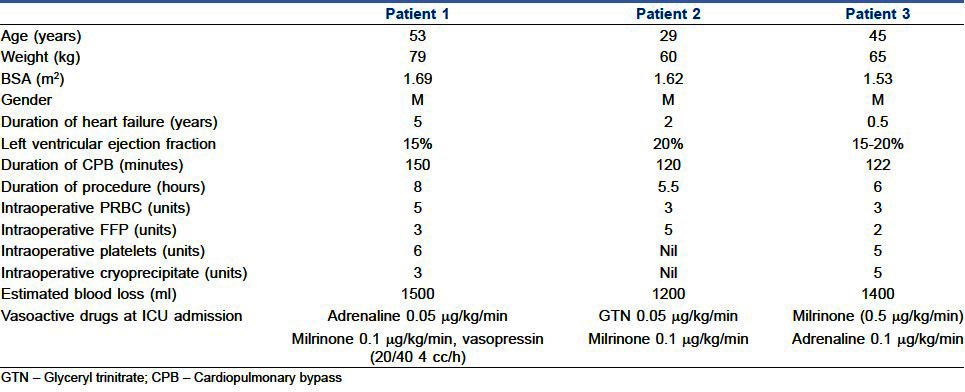

After verification of satisfactory positioning and function of the device with TOE, the effect of heparin was reversed with protamine, 1:1 ratio. Blood products were transfused as mentioned in Table 2. After stabilising the haemodynamics, de-cannulation of aorta and right atrium was performed. Chest was closed after achieving complete haemostasis. All the patients were sedated with propofol infusion (5-50 μg/kg/min) and transferred to the intensive care unit. Haemodynamic stability was maintained with inotropic drugs and pulmonary vasodilators as mentioned in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics and perioperative data

Postoperative course

Anticoagulation therapy with heparin was initiated and the dose was titrated to achieve activated partial thromboplastin time 45-55 s. Prophylactic antibiotic therapy was continued for 5 days postoperatively. Aspirin 150 mg/day was commenced on second postoperative day (POD) and warfarin on fifth POD. The dose of warfarin was titrated to maintain an international normalised ratio (INR) of 2 to 2.5. Inotropic supports were gradually reduced and patients were completely weaned from inotropes by 48-72 h postoperatively. Weaning from mechanical ventilation was done according to institutional protocol; patients 1 and 3 were extubated on third POD, but patient 2 was extubated on first POD. Small doses of morphine (2-5 mg increments) were administered as needed for analgesia before and after extubation.

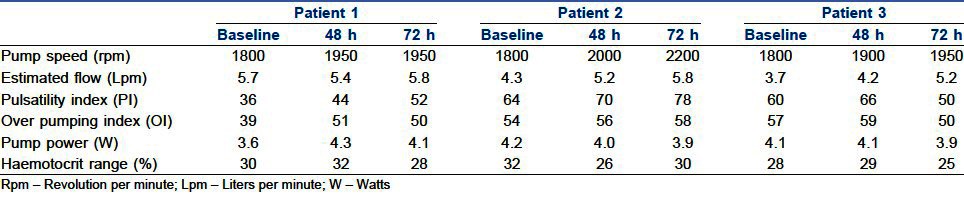

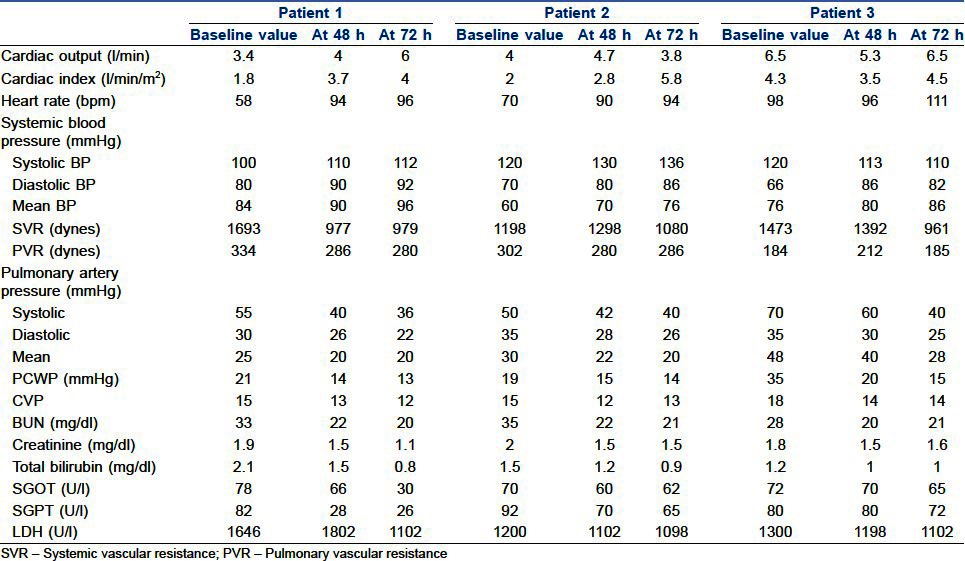

Perioperative data are shown in Table 2 and the VentrAssist pump parameters are shown in Table 3. Haemodynamic, renal and hepatic functions were improved in all patients when compared to preoperative values as shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Pump parameters

Table 4.

Baseline and 48 and 72 h post-implant haemodynamic data

All the patients underwent a structured physical rehabilitation programme. All of them were in NYHA class-I cardiac status at the time of discharge. All patients were discharged after 30 (mean) days of the LVAD implantation. At the time of writing, all the patients were at home in NYHA class I, able to perform activities of daily living and freely mobile in the community.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we describe implantation of the VentrAssist LVAD [Figure 1] which was successfully performed in patients with terminal heart failure. The VentrAssist is a third-generation centrifugal LVAD.[5–7] Anaesthetic management of these critically ill patients in heart failure, associated with renal and hepatic impairment, and presenting for repeat cardiac surgery is a challenge.[8] These patients were receiving amiodarone, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, β-blockers and diuretics. The data suggest that the combined use of amiodarone and ACE inhibitors might result in severe haemodynamic compromise during cardiac surgery.[4] A patient suffering from cardiac failure with hepatic and renal impairment may have significant altered pharmacokinetics for administered drugs.[9] The anaesthesiologist should be prepared to manage cardiac decompensation and acute desaturation before institution of CPB and severe coagulopathy bleeding after CPB.[10] These patients have a high incidence of perioperative infection, so appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis is imperative.

Figure 1.

The VentrAssist™ blood pump encased in a welded titanium shell and features a silicone percutaneous lead

To achieve these goals, we optimised these patients by inserting IABP under local anaesthesia;[11] triple lumen CVP cannula, radial artery cannula and wide bore peripheral cannula were also inserted under local anaesthesia, the day before surgery. The mean arterial pressure of more than 70 mmHg,[12] CVP of 8-10 mmHg and urine output of 1 ml/kg/h were maintained during perioperative period. In addition to these, metabolic acidosis was appropriately corrected. Perioperative bleeding is a major concern in these patients. This bleeding was multifactorial in origin (e.g., hepatic impairment, extensive surgery, redo surgery, effects of CPB, etc.), hence ε-aminocaproic acid was used.[13] We treated perioperative bleeding by administering blood products depending on the results of TEG.

Since the heart is beating during CPB, a good coronary perfusion pressure should be maintained and preparation should be made for managing right-sided heart failure, which occurs in 30% of patients.[14] To avoid hypothermia, all administered intravenous fluids should be warmed using warming devices such as hotline and also warming blankets are used.

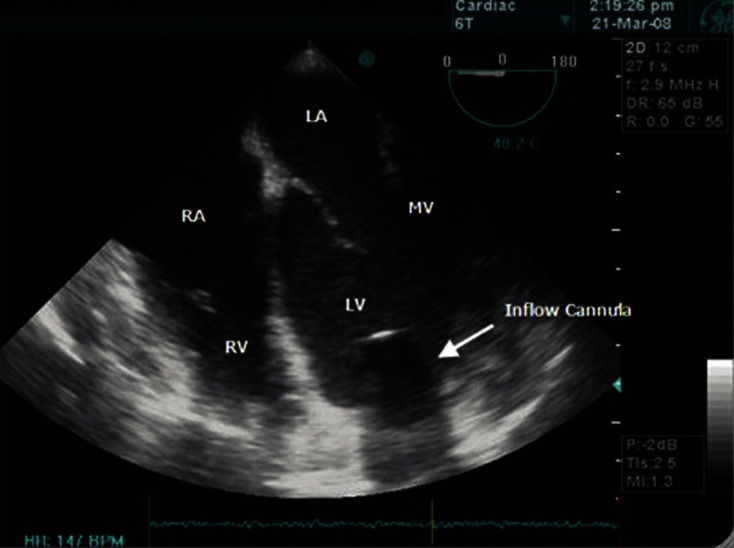

TOE examination is critically important during and after implantation of VentrAssist LVAD. In pre-bypass period, TOE was used to optimise left ventricular filling to maintain cardiovascular stability. Then, a thorough cardiac evaluation should be performed to ascertain whether a patent foramen ovale is present, using an agitated saline injection. If a patent foramen ovale is found, this needs to be repaired [Figure 2]. On CPB, TOE was used to ensure that inflow cannula of LVAD was appropriately directed away from left ventricular septum (to avoid inlet occlusion) and towards the mitral valve, so that the left ventricle can drain completely[15] [Figure 3]. TOE was also used for complete de-airing of all the chambers of the heart. The major concern on weaning from CPB is the right ventricular failure; TOE becomes a key monitor of right ventricular function. To treat right heart impairment preemptively, milrinone and adrenaline were started on CPB.[16] The VentrAssist is “preload dependent and afterload sensitive.” So, good right ventricular function and as low as possible pulmonary artery pressure are required for preload.[7]

Figure 2.

The bubble test in the mid-oesophageal bicaval view of transoesophageal echocardiography

Figure 3.

The position of the inlet cannulae from the left ventricle in the mid-oesophageal bicaval four-chamber view

The pulse pressure is influenced by LV contractility, intravascular volume, preload and afterload pressure, and by pump speed. Owing to the reduced pulse pressure during continuous flow LVAD support, it is often difficult to palpate a pulse and measure blood pressure accurately by the auscultatory or automated methods. In the early postoperative period, an arterial catheter is necessary to monitor blood pressure properly. After the arterial catheter was removed, the blood pressure was assessed using Doppler and transthoracic echocardiography (TTE). A flat arterial blood pressure waveform with a low pulse pressure indicates the LV function is extremely poor or that the set pump speed is close to exceeding the available preload (LV volume). When pulsatility is absent, ventricular suction and collapse are more likely to occur. It is desirable to have some arterial pulsatility and aortic valve opening support.[17]

A prospective, multicentre, international clinical trial has confirmed the favourable efficacy and safety profile of the VentrAssist patient.[8]

CONCLUSION

Anaesthetic management of patients undergoing VentrAssist LVAD implantation is unique. Our initial anaesthetic experience is promising.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge the kind acceptance and permission from Divine Patiag for publishing the images in this article.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Miller LW, Lietz K. Candidate selection for long term left ventricular assist device therapy for refractory heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:756–64. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esmore D, Rosenfeldt FL. Mechanical circulatory support for failing heart: Past, present and future. Heart Lung Circ. 2005;14:163–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicolas AC, Pagel PS. Perioperative considerations in the patients with a left ventricular assist device. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:565–70. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200302000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mets B, Michler RE, Delphin ED, Oz MC, Landry DW. Refractory vasodilation after cardiopulmonary bypass for heart transplantation in recipients on combined amiodarone and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy: A role for vasopressin administration. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1998;12:326–9. doi: 10.1016/s1053-0770(98)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venter Assist™ Left Ventricular Assist System -clinical instructions for use 2006. [Last accessed on 2012 Feb 08]. Available from: http://www.ventracor.com .

- 6.Esmore D, Sporatt P. Venter Assist™ left ventricular assist device: Clinical trial results and clinical development plan update. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;32:735–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esmore DS, Kaye D, Salamonsen R, Buckland M, Begg JR, Negri J, et al. Initial clinical experience with the VentrAssist left ventricular assist device: The pilot trial. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27:479–85. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oz M, Rose E, Levin H. Selection criteria for placement of left ventricular assist devices. Am Heart J. 1995;129:173–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mets B. Cardiac pharmacology. In: Thys D, editor. Text Book of Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldstein D, Seldomridge J, Chen J, Catanese KA, DeRosa CM, Weinberg AD, et al. Use of aprotonin in LVAD recipients reduces blood loss, blood use, and Perioperative mortality. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59:1063–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00086-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jhaveri R, Tardiff B, Stanley T. Anesthesia for heart and lung transplantation. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 1994;12:729–47. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blank T, Nyhan D, Kaplan J. Heart and heart lung-transplantation. In: Kaplan J, editor. Cardiac Anesthesia. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1993. pp. 905–16. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Livingston ER, Fisher CA, Bibidakis EJ, Pathak AS, Todd BA, Furukawa S, et al. Increased activation of the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems leads to hemorrhagic complications during left ventricular assist implantation. Circulation. 1996;94(II):227–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pavie A, Leger P. Physiology of univentricular versus biventdcular support. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:347–9. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)01026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanptman PJ, Body S, Fox J, Couper GS, Loh E. Implantation of a pulsatile external left ventricular assist device: Role of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography [see comments] J Cardiothorac Vase Anesth. 1994;8:340–1. doi: 10.1016/1053-0770(94)90249-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Argenziano M, Choudhri AF, Oz MC, Rose EA, Smith CR, Landry DW. A prospective randomized trial of arginine vasopressin in the treatment of vasodilatory shock after left ventricular assist device placement. Circulation. 1997;96:286–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slaughter MS, Pagani FD, Rogers JG, Miller LW, Sun B, Russell SD, et al. Clinical management of continuous flow left ventricular assist devices in advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:S1–39. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]