Abstract

Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related (ATR) kinases have been considered the primary activators of the cellular response to DNA damage. They belong to the protein kinase family, phosphoinositide 3-kinase–related kinase (PIKKs). In human beings, deficiency of these kinases leads to hereditary diseases, namely ataxia telangiectasia (AT) with ATM deficiency and ATR-Seckel with ATR deficiency. NBS1, a component of MRE11/RAD50/NBS1 (MRN) complex, is another important player in DNA damage response (DDR). Mutations of NBS1 are responsible for Nijmegen breakage syndrome (NBS), a human hereditary disease with the characteristics that almost encompassed those of AT and ATR-Seckel. NBS1 has been conventionally thought to be a downstream substrate of ATM and ATR in DDR; however, recent studies suggest that NBS1/MRN functions upstream of both ATM and ATR by recruiting them to the proximity of DNA damage sites and activating their functions. In this mini-review, we would emphasize the requirement of NBS1 as an upstream mediator for the modulation of PIKK family proteins ATM and ATR.

Keywords: DNA damage response, NBS1, PIKK

The DNA in our cells is under constant challenge by damaging agents, which include external factors, such as ultraviolet light (UV), ionizing radiation (IR), and other natural or man-made mutagens. It is also subject to damage by internal factors, including the byproducts of oxidative metabolism and stalled replication forks. Cells maintain a sophisticated system to deal with these damages. After the detection of the existence of DNA damage by sensor molecules, the DNA damage signals will be amplified and diversified, by signal transducers, to a set of downstream effectors. The downstream effectors trigger cellular events such as DNA repair, cell cycle checkpoint, telomere stability maintaenance, transcription control, and apoptosis. Together, the process mentioned above, are generally named DNA damage response (DDR). Failure of the appropriate DDR will lead to gene mutation or genomic instability, and such genomic changes are important mechanisms of carcinogenesis [1–3].

In mammalian cells, central to the DDR are ATM, ATR, and DNA-dependent protein catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs). They serve as DNA damage sensors that relay and amplify the damage signals to effectors controlling DDR. Numerous molecules are involved in PIKKs-mediated DDR (summarized in Table 1). Structural analysis reveals that ATM, ATR, and DNA-PKcs belong to a same protein kinase family, PIKKs. PIKKs are large molecules with homology in the catalytic domain to phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (Pl3K), but phosphorylate proteins rather than lipids. The catalytic domains of the PIKKs reside in their C-termini and account for only 5–10% of the total amino acids of these polypeptides. The catalytic domains of PIKKs function in targeting toward their substrates to trigger DDR[1]. ATM and DNA-PKcs respond mainly to DNA double strand breaks (DSB), whereas ATR is activated by single-stranded DNA and stalled replication forks. For ATM and ATR, the substrates mainly include factors involved in cell cycle checkpoint control such as CHK1, CHK2, p53, NBS1, SMC1, and BRCA1 [4]. For DNA-PKcs, the substrates mainly include factors involved in non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) DNA repair pathway, such as Ku70 and K80, Artemis, DNA ligase IV, and XRCC4 [5]. The bulk of the primary sequence residing in the N-termini of PIKKs contains >1500 amino acids and serves as the site of protein-to-protein interaction that regulates input and outflow of signals [6]. Acting as DNA damage sensors and signal transducers, ATM, ATR, and DNA-PKcs are conventionally considered to function at the top of the DDR network [1].

Table 1.

Molecules and their functions involved in DNA damage response

| Molecule | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| ATM, ataxia telangiectasia mutated | Member of the PIKK family of proteins that respond to DNA damage by phosphorylating key substrates involved in DNA repair, cell cycle control, and detection of damaged DNA | [32,33] |

| ATR, Ataxia- telangiectasia and Rad3-related | Member of the PIKK family of proteins involved in cell cycle progression, DNA recombination, and the detection of DNA damage. | [4,34] |

| DNA-PKcs, DNA-activated, catalytic subunit | Member of the PIKK family members involved in cell cycle control, DNA repair, and DNA damage detection. | [5,35] |

| Ku70,Ku antigen, 70-kd subunit. Ku80, Ku antigen, 80-kd subunit | Ku 70 and Ku80 form a Ku complex. The Ku complex binds to the ends of double-stranded DNA and functions in recruiting DNA-PKcs to DNA damage sites. | [36–38] |

| Artemis, DNA cross-link repair protein 1c | Artemis forms a complex with the DNA-PKcs. DNA-PKcs phosphorylates Artemis, and Artemis acquires endonucleolytic activity on 5′ and 3′ overhangs, as well as the opening of hairpins. | [39,40] |

| DNA ligase IV, Ligase IV; DNA, ATP-dependent | Form a complex with XRCC4 to ligate two juxtaposed DNA ends. | [41,42] |

| XRCC4, X-ray repair, complementing defective, in Chinese hamster, 4 | Form a complex with ligase IV to ligate two juxtaposed DNA ends. | [43,44] |

| NBS1, nibrin or p95 | Component of MRN complex, functions in DNA DSB repair, telomere maintenance, and cell cycle checkpoint control. NBS1 can be phsophorylated by ATM at serine 343 that relates with S phase checkpoint control. NBS1 functions in recruiting ATM to the DSB site and activate ATM function. | [10,12,45] |

| MRE11, Meiotic recombination 11 | MRE11 has DNA endo- and exo-nuclease activity, which is required to process DNA broken ends before rejoining. | [46,47] |

| RAD50 | DSB repair and chromosomal integration maintenance. | [48] |

| CHK1, Checkpoint kinase 1 | Integrate signals from ATM and ATR in response to DNA damage by delaying cell cycle progression in S and G2 phases. | [49,50] |

| CHK2, Checkpoint kinase 2 | In response to DNA damage, CHK2 phosphorylated CDC25C to prevent entry into mitosis, and phosphorylated p53 to elicit G1 block. | [51,52] |

| ATRIP, ATR-interacting protein | ATRIP recruits ATR to DNA damage site and trigger cell cycle checkpoint. | [29,53] |

| BRCA1, Breast cancer 1 gene | Breast cancer susceptibility gene, functions in DNA damage repair, replication, cell cycle checkpoint control, apoptosis, transcription, ubiquitination and chromatin remodeling. | [54,55] |

| p53, Tumor protein p53, or TP53 | Cell cycle checkpoint control, proliferation, transcription, DNA repair, apoptosis, and genomic stability maintenance. | [56,57] |

| HDM2, human homolog of mouse double minute 2 | Major regulator of p53 by targeting its destruction. | [58,59] |

| SMC1, Structure maintenance of chromosomes 1 | Sister chromatid cohesion during mitosis. | [60] |

NBS1 is another key player in DDR, as a component of MRE11/RAD50/NBS1 (MRN) complex. NBS1 itself does not have DNA binding/processing and kinase activity that are usually required for DNA damage repair. The FHA/BRCT domain in the N-terminus of NBS1, however, has been shown to bind directly to phosphorylated histone H2AX (γH2AX). The binding of NBS1 to γH2AX recruits other members of MRN (MRE11 and RAD50) to the proximity of DNA damage sites [7]. Certainly, other unknown γH2AX-independent mechanisms may also contribute to the binding of MRN to DNA ends [8]. MRE11 possesses several biochemical properties, such as 3′–5′ double-strand DNA exonuclease, single-strand DNA endonuclease, and DNA unwinding activity that are required for DNA DSB repair. RAD50 is a member of the structure maintenance of chromosome (SMC) protein family. RAD50 has two ATPase motifs at its N-and C-terminal ends and forms an anti-parallel homodimer with a flexible hinge region that may adopt a `V-like' conformation. The `V-like' structure could serve as a bridge to hold together the broken ends of DSB for avoiding them to float away, and to prevent excessive degradation of MRE11 by restricting its nucleotide degradation extent [9]. Several serine/glutamine motifs, consensus sequences of phosphorylation by ATM and ATR, are found at the central region of NBS1; these motifs are related to ATM and ATR-dependent cell cycle checkpoint activation and chromosomal stability maintenance [10,11]. Thus, NBS1 has been thought to be a downstream substrate of ATM and ATR [12,13].

Several phenomena, however, could not be explained by this traditional concept. It is wellknown that the key functions of ATM, ATR, and NBS1 in DDR are highlighted by the phenotypes displayed by AT patients with defective ATM, ATR-Seckel patients with defective ATR, and NBS patients with defective NBS1 [14,15]. Generally, overlapping and distinct abnormalities in phenotype were observed among patients with these gene defects. For instance, cell cycle checkpoint failure occurs in all NBS, AT, and ATR-Seckel patients; however, the immunodeficiency, chromosomal aberration and instability, cancer predisposition, cerebellar development defects, ataxia, and increased radiosensitivity are observed both in AT and NBS patients. Whereas, microcephaly, growth retardation, dysmorphic facial features are noted in ATR-Seckel and NBS patients [12,14,16–18]. Although human disease with DNA-PKcs deficiency has not been reported, severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice with a defective DNA-PKcs showed increased cancer incidence, immunodeficiency and chromosomal instability [5]. Clinically, AT and ATR-Seckel patients showed overlapping and distinct phenotypes, whereas the phenotypic alterations in NBS patients nearly encompassed all the phenotypic alterations observed in A-T and ATR-Seckel patients, and even the phenotypes found in SCID mice [5]. This observation suggests that NBS1 may work upstream of the PIKKs (ATM, ATR and PKcs) and the impaired functions of NBS1 will in turn impair the functions of these PIKKs. Therefore, NBS patients show a mixture of clinical manifestations observed in these PIKK defect syndromes.

This notion was further supported by recent evidence from several laboratory studies. Uziel et al. [19] found that ATM phosphorylation on serine 1981 was compromised in NBS1 defective cells following treatment with DSB inducing agents. Correspondingly, the nuclear retention of ATM (a sign of chromosomal binding) and the activation of ATM substrates, such as CHK2, p53, and HDM2, were also abrogated or attenuated in these NBS1 defective cells. Carson et al. [20] utilized adenovirous proteins E1b55k/E4orf6 to disrupt MRE11 complex in human cells, resulting in NBS1 dysfunction. These infected cells showed a marked reduction in ATM phosphorylation, ATM-dependent G2/M checkpoint abrogation, and the ATR-mediated DNA damage response deficiency after treatment with DSB-inducing agents. Similar results were obtained by Horejsi et al. [21] using NBS1 normal and deficient human fibroblast cells to investigate the time and magnitude of ATM activation by measuring the phosphorylation at ser1981 of ATM and at ser966 of ATM substrate SMC1. After exposure to 2 Gy IR, NBS1 normal cells showed a rapid phosphorylation of ATM at ser1981 and SMC1 at ser966. However, the IR-induced activation of ATM was abrogated or attenuated in NBS1 deficient cells. Furthermore, the attenuated IR-induced activation of ATM was rescued by retrovirally-mediated reconstitution of wild-type NBS1, but not by NBS1 lacking the MRE11 binding domain [21]. These results support the idea that NBS1/MRN functions is upstream of ATM and is required for ATM signaling in DDR [22].

Direct protein-to-protein interaction between MRN and ATM, as well as the modulation of the kinase activity of ATM were confirmed recently by Lee and Paull [23]. Using purified MRN and ATM proteins expressed in a baculovirus system, they performed in vitro kinase activity assay to show that MRN stimulated the kinase activity of ATM an in vitro toward its substrates p53, CHK2, and histone H2AX. By gel filtration assays, they showed that MRN had multiple contacts with ATM and stimulated ATM activity by facilitating stable binding to its substrates. To further investigate the role of MRN in the activation of ATM signaling by DSBs, they also tested whether the binding of ATM to DNA fragments depended on MRN [22]. The binding of MRN to DNA was found to be ATM independent, whereas ATM was bound to DNA only when MRN was associated. Furthermore, the unwinding of DNA ends by MRN was found to be essential for the stimulation of ATM activity. These results indicate that ATM activation by DSB through MRN complex is facilitated by ATM-DNA binding and the unwinding of DNA duplex [22]. Recently, a humanized NBS1 deficient transgenic mouse model was created, which bears a mutated human NBS1 gene expressing the minimum truncated C-terminal NBS1 protein and no endogenous mouse NBS1 protein. [24]. The NBS1 humanized mice showed both impairment of ATM activation and ATM-dependent IR-induced DDR. The NBS1 deficient animal model further supports the finding described above that NBS1 is an upstream mediator required for the activation of ATM [22,23].

Therefore, Stavridi and Halazonetis have recently proposed a model for the role of NBS1 in ATM activation at early and late phases in response to DSB [8]. The MRN complex is first recruited to the site of DSB through an unknown γH2AX-independent mechanism that may involve additional DNA DSB sensor proteins other than ATM (early time point). MRN subsequently recruits and activates ATM. Activated ATM phosphorylates histone H2AX and creats binding sites for the FHA/BRCT domain of NBS1, which in turn recruits additional MRN complexes further away from DNA ends. These MRN complexes then recruit and activate additional ATM molecules, leading to signal amplification and triggering DDR (late phase). In this manner, NBS1 functions together with ATM in an amplification loop, which allows even a small number of DNA DSBs to mount a potent DDR.

Based on these in vitro and in vivo findings, there is little doubt for NBS1 to function upstream of ATM in the DDR cascade; however, whether NBS1 also functions in the same way to modulate other PIKK members, such as ATR and DNA-PKcs, is currently unsolved. Stiff et al. [25] have performed a study using NBS1, ATM, and ATR-deficient cell lines to demonstrate that ATR-dependent phosphorylation could be facilitated by NBS1. They found that NBS1 deficient cell lines showed a defect in ATR-dependent phosphorylation of CHK1, c-jun, and p53 in response to UV irradiation- and hydroxyurea (HU)-induced replication stalling, which is similar to ATR defective cells. In addition, these defects were not found in the wild-type and ATM-deficient cell lines. Furthermore, other ATR-dependent events in response to HU, including the ubiquitination of FANCD2, G2/M checkpoint arrest, and the ability to restart DNA synthesis at stalled replication forks, were all observed to be impaired both in NBS1 and ATR deficient cell lines, but not in ATM-deficient cell lines [25]; strongly suggesting that NBS1 functions upstream of ATR-dependent signaling. Another piece of the indirect evidence to support this notion is from the study of Falck et al. [26], who discovered that a conserved C-terminal motif in NBS1 serves to recruit activated ATM to the sites of DNA damage and promoted the phosphorylation of ATM substrates. Strikingly, the motif shares sequence homology to the C-terminus of ATRIP and Ku80 that were required to recruit ATR and DNA-PKcs to sites of DNA damages, respectively [27–31] suggesting a common mechanism of PIKKs activation. Whether NBS1 can play the same role as ATRIP and Ku80 to recruit ATR and DNA-PKcs to sites of DNA damage remains unclear. However, the synthesized NBS1 C-terminal peptide with this motif was able to interact with DNA-PKcs from extracts derived from Hela cells (25), suggesting a possible solution for this question. In another word, NBS1 may function as an upstream mediator in the modulation of not only ATM, but also other PIKKs members in the DDR network; ATR and probably DNA-PKcs are the most likely candidates for these PIKKs. It would be interesting to explore whether ATRIP or Ku80 cross-react with PIKKs other than ATR and DNA-PKcs in further studies; which will be of extreme significance to the understanding of the early events in the DNA damage signaling cascade.

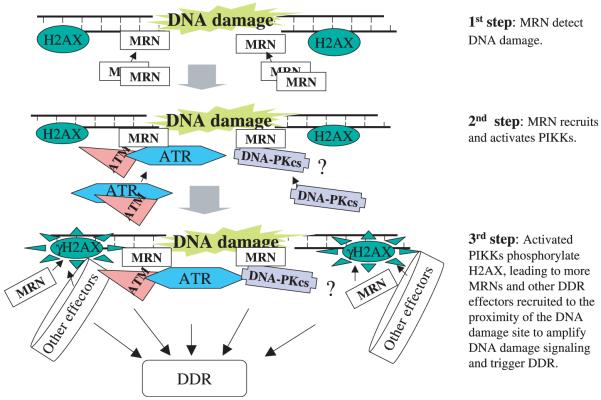

In conclusion, recent studies on the proteins underlying human diseases or mouse model (AT, ATR-Seckel, NBS, and SCID mice) characterized by cancer predisposition and impaired DDR have advanced our understanding of the early events of DDR. The current knowledge obtained from clinical observations and experimental studies leads to the new concept that NBS1 is not only involved in certain downstream steps of ATM-dependent DNA repair response but also functions as an upstream mediator of, and is required for the ATM signaling in DDR. Whether or not NBS1 also works in the same manner in ATR- or DNA-PKcs-dependent DDR as ATM, requires further study. We believe that, like the relationship of ATM and NBS1, the network relation of ATR and DNA-PKcs to NBS1 will be clarified as state-of-the-art techniques are developed. Based on the published data, a 3-step model of the role of NBS1 in ATM, ATR, and DNA-PKcs activities in DDR is outlined in Fig. 1. This proposed model indicates that NBS1 may not only function in DSB repair as an effector protein, but also may act as an important DNA damage sensor and signal transducer. To delineate the molecular mechanisms by which NBS1 modulate the PIKK family in response to DDR has great potential for clinical studies to enhance the tumor-cell-killing effects of treatments such as IR and some chemotherapeutic agents (3).

Fig. 1.

A 3-step model of the role of NBS1 in DDR. The MRN complex is recruited by an unknown `γH2AX-independent mechanism' to the DNA damage sites (step 1) (8). Then, the PIKKs (DNA-PKcs could be one of them) are recruited to the DNA damage sites (by a conserved region in the C-terminus of NBS1) and their functions are activated (facilitated by the strand dissociation, nuclease, and chromatin structure maintenance activities of MRE11 and RAD50) (Step 2) (26). The recruited PIKKs phosphorylate H2AX, which leads to the accumulation of MRN and other DDR effectors to the proximity of DNA damage sites, thus triggering DDR. Here, NBS1 may function as a substrate of PIKKs by the phosphorylation of serine/glutamine motifs in the central region of NBS1 by PIKKs.

Acknowledgements

The work related to this mini-review is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health RO1 CA 101990 and the US Department of Energy the Office of Science Grant No. DE-FG02-05ER63945 (to J.J.L.).

References

- [1].Abraham RT. PI 3-kinase related kinases: `big' players in stress-induced signaling pathways. DNA Repair. 2004;3:883–887. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jackson SP. Sensing and repairing DNA double-strand breaks. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:687–696. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.5.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zhang Y, Lim CUK, Williams ES, Zhou J, Zhang Q, Fox MH, et al. NBS1 knockdown by small interfering RNA increases ionizing radiation mutagenesis and telomere association in human cell. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5544–5553. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kurz EU, S, Lees-Miller SP. DNA damage-induced activation of ATM and ATM-dependent signaling pathways. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:889–900. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Collis SJ, DeWeese TL, Jeggo PA, Parker AR. The life and death of DNA-PK. Oncogene. 2005;24:949–961. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Perry J, Kleckner N. The ATRs, ATMs, and TORs are giant HEAT repeat proteins. Cell. 2003;112:151–155. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Tauchi HK, Kobayashi J, Morishima K, Matsuura S, Nakamura A, Shiraishi T, et al. The forkhead-associated domain of NBS1 is essential for nuclear foci formation after irradiation but not essential for hRAD50/hMRE11/NBS1 complex DNA repair activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:12–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000578200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Stavridi ES, Halazonetis TD. Nbs1 moving up in the world. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:648–650. doi: 10.1038/ncb0705-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].D'Amours D, Jackson SP. The Mre11 complex: at the crossroads of DNA repair and checkpoint signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:317–327. doi: 10.1038/nrm805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lim DS, Kim ST, Xu B, Maser RS, Lin J, Petrini JH, Kastan MB. ATM phosphorylates p95/nbs1 in an S-phase checkpoint pathway. Nature. 2000;404:613–617. doi: 10.1038/35007091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bai Y, Murnane JP. Telomere instability in a human tumor cell line expressing NBS1 with mutations at sites phosphorylated by ATM. Mol. Cancer Res. 2003;1:1058–1069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tauchi H, Matsuura S, Kobayashi J, Sakamoto S, Komatsu K. Nijmegen breakage syndrome gene, NBS1, and molecular links to factors for genome stability. Oncogene. 2002;21:8967–8980. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Eyfjord JE, Bodvarsdottir SK. Genomic instability and cancer: networks involved in response to DNA damage. Mutat. Res. 2005;592:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].O'Driscoll M, Gennery AR, Seidel J, Concannon P, Jeggo PA. An overview of three new disorders associated with genetic instability: LIG4 syndrome, RS-SCID and ATR-Seckel syndrome. DNA Repair. 2004;3:1227–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].O'Driscoll M, Ruiz-Perez VL, Woods CG, Jeggo PA, Goodship JA. A splicing mutation affecting expression of ataxia-telangiectasia and rad3-related protein (ATR) results in seckel syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2003;33:497–501. doi: 10.1038/ng1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Frappart PO, Tong WM, Demuth I, Radovanovic I, Herceg Z, Aguzzi A, et al. An essential function for NBS1 in the prevention of ataxia and cerebellar defects. advanced online publication. Nat. Med. 2005;11:538–544. doi: 10.1038/nm1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tauchi H, Kobayashi J, Morishima K, van Gent DC, Shiraishi T, Verkaik NS, et al. Nbs1 is essential for DNA repair by homologous recombination in higher vertebrate cells. Nature. 2002;420:93–98. doi: 10.1038/nature01125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Shiloh Y. Ataxia-telangiectasia and the nijmegen breakage syndrome: related disorders but genes apart. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1997;31:635–662. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.31.1.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Uziel T, Lerenthal Y, Moyal L, Andegeko Y, Mittelman L, Shiloh Y. Requirement of the MRN complex for ATM activation by DNA damage. Eur Mol. Biol. Org. J. 2003;22:5612–5621. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Carson CT, Schwartz RA, Stracker TH, Lilley CE, Lee DV, Weitzman MD. The Mre11 complex is required for ATM activation and the G2/M checkpoint. Eur Mol. Biol. Org. J. 2003;22:6610–6620. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Horejsi Z, Falck J, Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB, Lukas J, Bartek J. Distinct functional domains of Nbs1 modulate the timing and magnitude of ATM activation after low doses of ionizing radiation. Oncogene. 2004;23:3122–3127. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lee JH, Paull TT. ATM activation by DNA double-strand breaks through the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 complex. Science. 2005;308:551–554. doi: 10.1126/science.1108297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lee JH, Paull T. Direct activation of the ATM protein kinase by the Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 complex. Science. 2004;304:93–96. doi: 10.1126/science.1091496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Difilippantonio S, Celeste A, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Chen HT, Martin BR, Laethem FV, et al. Role of Nbs1 in the activation of the Atm kinase revealed in humanized mouse models, Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:675–685. doi: 10.1038/ncb1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Stiff T, Reis C, Alderton GK, Woodbine L, O'Driscoll M, Jeggo PA. Nbs1 is required for ATR-dependent phosphorylation events. Eur Mol. Biol. Org. J. 2005;24:199–208. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Falck J, Coates J, Jackson SP. Conserved modes of recruitment of ATM, ATR and DNA-PKcs to sites of DNA damage. Nature. 2005;434:605–611. doi: 10.1038/nature03442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Unsal-Kacmaz K, Sancar A. Sancar, quaternary structure of ATR and effects of ATRIP and replication protein A on its DNA binding and kinase activities. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;24:1292–1300. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1292-1300.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Osborn AJ, Elledge SJ, Zou L. Checking on the fork: the DNA-replication stress–response pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:509–516. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02380-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zou L, Elledge SJ. Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science. 2003;300:1542–1548. doi: 10.1126/science.1083430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gottlieb TM, Jackson SP. The DNA-dependent protein kinase: requirement for DNA ends and association with Ku antigen. Cell. 1993;72:131–142. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90057-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Dvir A, Peterson SR, Knuth MW, Lu H, Dynan WS. Ku autoantigen is the regulatory component of a template-associated protein kinase that phosphorylates RNA polymerase II. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:11920–11924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kapp LN, Painter RB, Yu LC, van Loon N, Richard CW, James MR, et al. Cloning of a candidate gene for ataxiatelangiectasia group D. Am J. Hum. Genet. 1992;51:45–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Shiloh Y. ATM: ready, set, go. Cell Cycle. 2003;2:116–117. doi: 10.4161/cc.2.2.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Cimprich KA, Shin TB, Keith CT, Schreiber SL. cDNA cloning and gene mapping of a candidate human cell cycle checkpoint protein, Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:2850–2855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hartley KO, Gell D, Smith GC, Zhang H, Divecha N, Connelly MA, et al. DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit: a relative of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and the ataxia telangiectasia gene product. Cell. 1995;82:849–856. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90482-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Reeves WH, Sthoeger ZM. Molecular cloning of cDNA encoding the p70 (Ku) lupus autoantigen. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:5047–5052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Koike M, Matsuda Y, Mimori T, Harada YN, Shiomi N, Shiomi T. Chromosomal localization of the mouse and rat DNA double-strand break repair genes Ku p70 and Ku p80/XRCC5 and their mRNA expression in various mouse tissues. Genomics. 1996;38:38–44. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Koike M, Koike A. The Ku70-binding site of Ku80 is required for the stabilization of Ku70 in the cytoplasm, for the nuclear translocation of Ku80, and for Ku80-dependent DNA repair. Exp. Cell Res. 2005;305:266–276. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ma Y, Pannicke U, Schwarz K, Lieber MR. Hairpin opening and overhang processing by an artemis/DNA-dependent protein kinase complex in nonhomologous end joining and V(D)J recombination. Cell. 2002;108:781–794. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Moshous D, Callebaut I, de Chasseval R, Corneo B, Cavazzana-Calvo M, Le Deist F, et al. Artemis, a novel DNA double-strand break repair/V(D)J recombination protein, is mutated in human severe combined immune deficiency. Cell. 2001;105:177–186. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00309-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wei YF, Robins P, Carter K, Caldecott K, Pappin DJ, Yu GL, et al. Molecular cloning and expression of human cDNAs encoding a novel DNA ligase IV and DNA ligase III, an enzyme active in DNA repair and recombination. Mol. Cell Biol. 1995;15:3206–3216. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Grawunder U, Zimmer D, Fugmann S, Schwarz K, Lieber MR. DNA ligase IV is essential for V(D)J recombination and DNA double-strand break repair in human precursor lymphocytes. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:477–484. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Li Z, Otevrel T, Gao Y, Cheng HL, Seed B, Stamato TD, et al. The XRCC4 gene encodes a novel protein involved in DNA double-strand break repair and V(D)J recombination. Cell. 1995;83:1079–1089. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Weterings E, van Gent DC. The mechanism of nonhomologous end-joining: a synopsis of synapsis. DNA Repair. 2004;3:1425–1435. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Varon R, Vissinga C, Platzer M, Cerosaletti KM, Chrzanowska KH, Saar K, et al. Nibrin, a novel DNA double-strand break repair protein, is mutated in nijmegen breakage syndrome. Cell. 1998;93:467–476. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Paull TT, Gellert M. The 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity of Mre 11 facilitates repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Mol. Cell. 1998;1:969–979. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Petrini JH, Walsh ME, DiMare C, Chen XN, Korenberg JR, Weaver DT. Isolation and characterization of the human MRE11 homologue. Genomics. 1995;29:80–86. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Dolganov GM, Maser RS, Novikov A, Tosto L, Chong S, Bressan DA, Petrini JH. Human rad50 is physically associated with human Mre11: identification of a conserved multiprotein complex implicated in recombinational DNA repair. Mol. Cell Biol. 1996;16:4832–4841. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Flaggs G, Plug AW, Dunks KM, Mundt KE, Ford JC, Quiggle MR, et al. Atm-dependent interactions of a mammalian chk1 homolog with meiotic chromosomes. Curr. Biol. 1997;7:977–986. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00417-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Zhao H, Watkins JL, Piwnica-Worms H. Disruption of the checkpoint kinase 1/cell division cycle 25A pathway abrogates ionizing radiation-induced S and G2 checkpoints. Proc. Natl Acad Sci. USA. 2002;99:14795–14800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182557299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Matsuoka S, Huang M, Elledge SJ. Linkage of ATM to cell cycle regulation by the Chk2 protein kinase. Science. 1998;282:1893–1897. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Chehab NH, Malikzay A, Appel M, Halazonetis TD. Chk2/hCds1 functions as a DNA damage checkpoint in G(1) by stabilizing p53. Genes Dev. 2000;14:278–288. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Cortez D, Guntuku S, Qin J, Elledge SJ. ATR and ATRIP: partners in checkpoint signaling. Science. 2001;294:1713–1716. doi: 10.1126/science.1065521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Zhang J, Powell SN. The role of the BRCA1 tumor suppressor in DNA double-strand break repair. Mol. Cancer Res. 2005;3:531–539. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Zhang J, Willers H, Feng Z, Ghosh JC, Kim S, Weaver DT, et al. Chk2 phosphorylation of BRCA1 regulates DNA double-strand break repair. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;24:708–718. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.2.708-718.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. p53 function and dysfunction. Cell. 1992;70:523–526. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90421-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Honma M. Generation of loss of heterozygosity and its dependency on p53 status in human lymphoblastoid cells. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2005;45:162–176. doi: 10.1002/em.20113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Momand J, Zambetti GPGP, Olson DC, George D, Levine AJ. The mdm-2 oncogene product forms a complex with the p53 protein and inhibits p53-mediated transactivation. Cell. 1992;69:1237–1245. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90644-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Momand J, Zambetti GP. Mdm-2: `big brother' of p53. J. Cell. Biochem. 1997;64:343–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Gruber S, Haering CH, Nasmyth K. Chromosomal cohesin forms a ring. Cell. 2003;112:765–777. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]