Abstract

Background

Biochemical markers of altered mineral metabolism have been associated with increased mortality in end stage renal disease patients. Several studies have demonstrated non-linear (U-shaped or J-shaped) associations between these minerals and mortality, though many researchers have assumed linear relationships in their statistical modeling. This analysis synthesizes the non-linear relationships across studies.

Methods

We updated a prior systematic review through 2010. Studies included adults receiving dialysis and reported categorical data for calcium, phosphorus, and/or parathyroid hormone (PTH) together with all-cause mortality. We performed 2 separate meta-analyses to compare higher-than-referent levels vs referent and lower-than-referent levels vs referent levels.

Results

A literature review showed that when a linear relationship between the minerals and mortality was assumed, the estimated associations were more likely to be smaller or non-significant compared to non-linear models. In the meta-analyses, higher-than-referent levels of phosphorus (4 studies, RR = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.15-1.25), calcium (3 studies, RR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.05-1.14), and PTH (5 studies, RR = 1.11, 95% CI = 1.07-1.16) were significantly associated with increased mortality. Although no significant associations between relatively low phosphorus or PTH and mortality were observed, a protective effect was observed for lower-than-referent calcium (RR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.83-0.89).

Conclusions

Higher-than-referent levels of PTH, calcium, and phosphorus in dialysis patients were associated with increased mortality risk in a selection of observational studies suitable for meta-analysis of non-linear relationships. Findings were less consistent for lower-than-referent values. Future analyses should incorporate the non-linear relationships between the minerals and mortality to obtain accurate effect estimates.

Keywords: Calcium, Dialysis, Meta-analysis, Mineral metabolism, Mortality, Parathyroid hormone

Background

Among patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD), the deterioration of kidney function is often accompanied by secondary hyperparathyroidism (SHPT) involving disturbances in mineral metabolism, including elevated levels of serum phosphorus, decreased calcium, and elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) [1,2]. Observational studies suggest that biochemical markers of altered mineral metabolism are associated with poor clinical outcomes among patients with ESRD requiring dialysis, although controversy exists regarding the strength of the evidence and the independent nature of these relationships [3-16].

In a systematic review published in 2008, Covic et al. [17] identified 22 studies published from 1980–2007 that assessed the association between disturbances in biochemical parameters and all-cause mortality among patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), including 19 studies of patients on dialysis. The authors noted that the studies were too clinically and methodologically diverse to permit an appropriate meta-analysis. Nevertheless, a qualitative assessment of the studies led them to conclude that elevated values in certain biochemical parameters, specifically the serum levels of PTH, calcium, and phosphorus, as well as very low values of phosphorus, were associated with an increase in mortality risk among patients on dialysis.

In contrast to Covic et al., Palmer et al. [18] concluded from their meta-analysis that calcium and PTH did not have statistically significant associations with mortality, but an association between high serum phosphorus and mortality was observed (relative risk [RR] = 1.18, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.12-1.25). The Palmer et al. meta-analysis assumed a linear relationship between the serum levels of the 3 biochemical parameters and all-cause mortality, a limitation that they acknowledged could have biased their results.

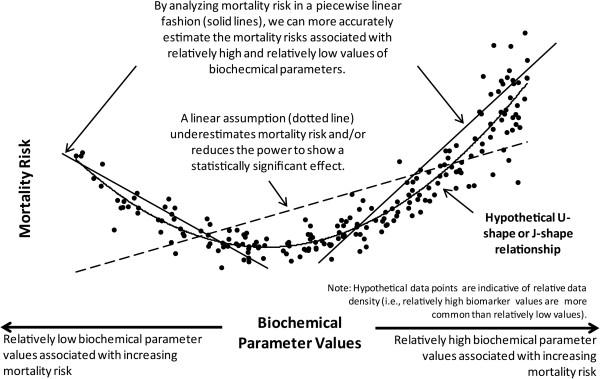

How the biochemical parameters are modeled is crucial. If the true relationship between the biochemical parameters and mortality is indeed U-shaped or J-shaped, then imposing linear assumptions on a model (either within an individual study or in a meta-analysis) would not accurately quantify the true association (see Figure 1). Often a continuous risk predictor such as age is modeled “as is” without transformations. By doing so, a linear relationship between the predictor and outcome is assumed. If its risk ratio is significantly above 1, then the model implies that for every additional unit (eg, year), the risk increases by a certain constant amount. However, it is possible that both very high and very low values of a variable could increase the risk. Some studies have demonstrated non-linear associations (eg, U-shaped, J-shaped) between phosphorus, calcium, and PTH and mortality risk whereby both low and high serum levels of these variables are associated with an increased risk of death [10,14-16,19-24]. In addition, there is evidence suggesting mortality risk is influenced by interactions between serum calcium and phosphorus [5,22,25].

Figure 1.

Hypothesized relationship between biochemical parameters and mortality risk.

These findings suggest that more advanced statistical methods are required to adequately quantify the true relationship between these biochemical abnormalities and mortality risk in ESRD patients. Researchers have categorized markers (eg, quintiles, high/normal/low groups) as a way to account for non-linear relationships. A few have more rigorously used spline terms [20,21,26] (ie, mathematical functions used to model non-linear relationships) and/or tested for interactions [22,25] (effect modifiers). Unfortunately, since modeling non-linear relationships in regression models is complex, many studies have failed to do so, and the studies that have examined non-linear relationships between biochemical measures and mortality often have not provided results in a format amenable to a traditional meta-analysis.

Thus, the purpose of this study is two-fold. We will review the literature with a special emphasis on the statistical methods used to model the serum levels of PTH, phosphorus, and calcium with mortality. Next, we will use more statistically rigorous meta-analytic methods to improve the estimates of the relationships between biochemical markers of altered mineral metabolism and mortality among patients on dialysis.

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

We searched PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane for English-language articles published subsequent to Covic et al.’s review (ie, 2008–2010) using a search strategy that included terms related to the population, biochemical parameters, and outcomes of interest (see Additional file 1). We reviewed the studies on all-cause mortality among patients on dialysis that were cited by Covic et al. [17] and Palmer et al. [18]. We also reviewed reference lists of relevant primary research and review articles for additional publications.

Initial inclusion criteria and data abstraction

To be included in this review, studies had to (1) have a patient population comprised of adults receiving hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis; (2) report data on at least one of the selected biochemical parameters, namely calcium, phosphorus, and PTH; and (3) report findings for all-cause mortality. We excluded studies of patients not on dialysis (eg, pre-dialysis CKD, status post-renal transplant) as well as studies that only reported data on calcium-phosphorus product.

Relevant data from each study were abstracted into an evidence table by one investigator (JLN) and were verified by the study statistician (BHN) prior to use in the meta-analysis. Data elements included study characteristics (eg, study design, analytic approach, duration of follow-up), patient characteristics (eg, dialysis type and vintage, age, gender), biochemical parameters and units, time of measurement of biochemical parameters (eg, baseline, time-averaged), and mortality/survivor data.

Literature assessment

For each manuscript that presented a correlation of all-cause mortality data with the biochemical measures of interest, we noted if the authors modeled the biochemical parameters as linear (ie, continuous) predictors of mortality or if they allowed a non-linear relationship with mortality (eg, modeled with splines, modeled as a categorical or binary variable). We also noted if figures were plotted showing the relationship between the parameters and mortality.

Primary meta-analysis approach

To better approximate possible non-linear relationships between biochemical parameters and mortality, we assumed a piecewise linear relationship between each parameter and mortality, and we used each publication’s study-defined referent category. We then performed 2 separate meta-analyses to compare (1) values higher than the referent category vs referent, and (2) values lower than the referent category vs referent.

To be included in the quantitative meta-analysis, each study had to report data on PTH, calcium, and/or phosphorus as categorical variables with the following requirements: (1) the ranges of each category must be specified, (2) the referent category in the study’s multivariate analysis must be the “middle” (ie, both higher-than-referent and lower-than-referent categories were available for comparison), (3) the sample size of each category must be given, and (4) the number of deaths of patients in the multivariate analysis must be given. We also excluded studies with inadequate multivariate analysis (eg, only crude unadjusted results provided, only 1–2 covariates). When RRs were presented graphically without explicit quantitative details, we used a “pencil and ruler” method to extrapolate these values. We did not attempt to contact study authors to inquire about missing data or exact values of graphical data elements.

We also attempted to capture the following statistics for each study: (1) number of deaths per category, (2) person-years per category, (3) covariates in multivariate models, and (4) overall mean and SD of the biochemical parameter and the mean and SD at each categorical level. Unfortunately, both the number of deaths and person-years per biochemical parameter category were not reported in the studies that met our inclusion criteria, and the other statistics were often missing as well.

For the quantitative analysis, we employed the meta-analytic method proposed by Greenland and Longnecker [27] to handle results presented as categorically (with a referent level) and subsequently adapted and expanded upon by Hamling et al. [28]. The Hamling method allows for alternative comparisons of categorical data and is useful when the threshold values in each category are not uniform across studies. For example, studies of cigarette smoking exposure and cancer may present results based on number of pack-years of exposure, and those categories vary across studies. By applying Hamling’s method, one can group dissimilar categories to permit more consistent comparisons across disparate studies (eg, a meta-analysis of any smoking exposure vs. no smoking exposure). In our context, these were relatively high (or low) biochemical parameter values compared to referent.

We used the method of Hamling et al. [28] to derive 2 adjusted RR estimates for each study, one for high values versus the reference range and another for low values versus the reference range. These results were derived from the hazard ratios (HRs) given at the various categorical levels in each study after a multivariate Cox-regression was performed. We assumed a piecewise linear relationship between mortality and the biochemical parameter levels (categories) and that a correlated (non-zero) covariance exists among the series of log RRs. As such, we estimated a variance-covariance matrix of the beta coefficients using the meta-analytic method proposed by Greenland and Longnecker [27]. We also created a meta-regression with the dose estimate at the study level and the time to follow up at the study level as the independent covariate.

All meta-analyses were done with Stata 11.1, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX. Results from the Hamling method were derived from an Excel macro available at http://www.pnlee.co.uk/software.htm[28].

Sensitivity analyses

Since the Hamling method requires an estimate of the number of deaths in the referent category and this was unknown, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by varying our initial mortality estimates in 2 ways: (1) 10% and 15% higher number of deaths, and (2) 10% and 15% lower number of deaths. These cutoffs were selected based on an educated assessment of our uncertainty regarding the number of deaths in the referent category. We then regenerated the meta-analysis results and examined how these variations affected the RRs.

Simulation modeling

As an exploratory analysis, we simulated patient-level results from 5 observational studies selected for large sample size (Block et al. [10], Floege et al. [16], Kalantar-Zadeh et al. [14], Slinin et al. [5], and Tentori et al. [15]). Data for the 3 biochemical parameters were simulated for each of 100,000 hypothetical patients using a lognormal distribution calibrated from the published data of the 5 studies (eg, frequency distribution, mean, standard deviation, correlations between parameters) in order to optimally account for differences in categorization of the biochemical parameters by the respective observational studies. A non-linear dose-effect function (with functional form based on Floege et al. [16]) was applied to the simulated data and calibrated from the observed results. Simulation models were performed using Python 2.6.6 with NumPy 1.5.1rc2 and SciPy 0.8.0.

Results

Overview of studies

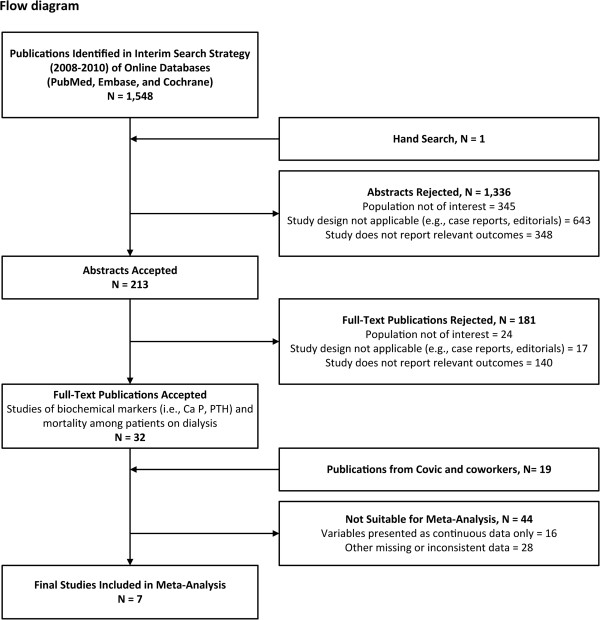

The interim search strategy identified 1,548 publications. We ultimately identified 51 studies among patients on dialysis that presented all-cause mortality data correlated with the biochemical measures of interest (see Figure 2 and Table 1).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram: publications documenting the association between relatively high/low biochemical parameters and mortality.

Table 1.

Overview of accepted publications

| Author, year | Study or database name | Study design | Duration of follow-up | Dialysis vintage | Dialysis type | Sample size | Allowed for non-linear relationship?* |

Was the biochemical parameter associated with mortality after multivariate adjustment? |

Graphical depiction?† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTH | Phosphorus | Calcium | |||||||||

|

Studies with adequate data for meta-analysis | |||||||||||

| Block 2004 [10] |

Fresenius Medical Care |

Retrospective cohort |

12-18 months (total) |

Maintenance |

HD |

40,538 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes (U-shaped for calcium, linear for albumin-adjusted calcium) |

| Dukkipati 2010 [29] |

DaVita-NIED |

Prospective cohort |

63 months (total) |

Maintenance |

HD |

748 |

Yes (for PTH only) |

Yes |

Not stated |

Not stated |

No |

| Floege 2011 [16] |

European Fresenius Medical Care |

Retrospective cohort |

20.9 months (median) |

Incident or Maintenance |

HD |

7,970 |

Yes (also used fractional polynomials) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Kalantar-Zadeh 2006 [14] |

DaVita |

Prospective cohort |

24 months (total) |

Maintenance |

HD |

58,058 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Rodriguez-Benot 2005 [24] |

Cordoba, Spain |

Prospective cohort |

97.6 months (median) |

Maintenance |

HD |

385 |

Yes (for phosphorus and PTH only) |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Tangri 2011 [30] |

UKRR |

Prospective cohort |

24 months (total) |

Incident |

HD, PD |

7,076 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Tentori 2008 [15] |

Dialysis Clinic Inc. |

Prospective cohort |

16.4 months (median) |

Maintenance |

HD |

25,588 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Studies that did not qualify for meta-analysis | |||||||||||

| Block 1998 [31] |

USRDS (CMAS and DMMS-1) |

Retrospective cohort |

2 years |

Maintenance |

HD |

6,407 |

Yes (also analyzed as continuous linear predictor) |

No |

Yes |

Yes (text and figure are inconsistent) |

Yes (J-shaped for phosphorus, linear for calcium and PTH) |

| Block 2010 [32] |

DaVita, CMS-ESRD |

Prospective cohort |

2.2 years |

Maintenance |

HD |

25,150 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Chang 2006 [33] |

VA Cooperative Study #440 |

Post-hoc RCT |

4 years |

Incident or Maintenance |

HD |

197 |

Yes |

No |

Not measured |

Not measured |

No |

| Dreschler 2011 [34] |

NECOSAD |

Prospective cohort |

6 years |

Incident |

HD, PD |

1,628 |

Yes (for PTH only) |

Yes |

Not stated |

Not stated |

No |

| Dreschler 2011 [35] |

NECOSAD |

Prospective cohort |

3 years |

Incident |

HD, PD |

762 |

No |

Not stated |

Not stated |

Not stated |

No |

| Etter 2010[36] |

monitor! |

Prospective cohort |

562 days (median) |

Maintenance |

HD |

170 |

No |

No |

Not measured |

Not measured |

No |

| Foley 1996 [37] |

Royal Victoria Hospital |

Prospective cohort |

5 years |

Incident |

HD, PD |

433 |

Yes (calcium and phosphorus were binary) |

Not measured |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Ganesh 2001 [7] |

USRDS (CMAS and DMMS 1/3/4) |

Retrospective cohort |

2 years |

Maintenance |

HD |

12,833 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not stated |

Yes (U-shaped for PTH) |

| Gutierrez 2008 [38] |

ArMORR (Fresenius) |

Prospective cohort |

1 year |

Incident |

HD |

10,044 |

Yes (for phosphorus only) |

Not stated |

Yes |

Not stated |

No |

| Hakemi 2010 [39] |

Tehran, Iran |

Prospective cohort |

18.4 months (mean) |

Maintenance |

PD |

282 |

Yes (for calcium and PTH only, binary) |

Yes |

Not measured |

Yes |

No |

| Hsiao 2011 [40] |

Chang Gung Memorial Hospital |

Prospective cohort |

1 year |

Maintenance |

HD |

109 |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Isakova 2009 [41] |

ArMORR (Fresenius) |

Prospective cohort |

1 year |

Incident |

HD |

10,044 |

Yes (for phosphorus only) |

Not stated |

Yes |

Not stated |

No |

| Jassal 1996 [42] |

Belfast City Hospital |

Prospective cohort |

1 year |

Incident |

NR |

99 |

No |

Not measured |

Yes (but not on older subset of patients) |

Not measured |

No |

| Jean 2009 [43] |

Tassin la Demi-lune, France |

Prospective cohort |

2 years |

Maintenance |

HD |

219 |

Yes (for phosphorus only, Not stated for PTH and calcium) |

Not stated |

No |

Not stated |

No |

| Kalantar-Zadeh 2010 [44] |

DaVita-Los Angeles |

Prospective cohort |

5 years |

Incident or Maintenance |

HD |

139,328 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes (except for PTH) |

| Kimata 2007 [45] |

DOPPS 1/2 (Japan) |

Retrospective cohort |

8,056 patient-years |

Maintenance |

HD |

3,973 |

Yes (also analyzed as continuous linear predictors) |

Yes, when linear No, when categorical |

Yes, when categorical No, when linear |

Yes, for both categorical and linear |

Yes for phosphorus No for calcium or PTH |

| Komaba 2008 [46] |

Takasago, Japan |

Retrospective cohort |

45 months |

Maintenance |

HD |

99 |

Yes (binary only) |

No |

Yes (but analyzed with calcium only) |

Yes (but analyzed with phosphorus only) |

No |

| Lacson 2009 [47] |

Fresenius Knowledge Center |

Retrospective cohort |

1 year |

Maintenance |

HD |

78,420 |

In some models |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Leggat 1998 [48] |

USRDS (CMAS and DMMS) |

Retrospective cohort |

2 years |

Maintenance |

HD |

6,251 |

Yes |

Not measured |

Yes |

Not measured |

No |

| Lin 2010 [49] |

Chang Gung Memorial Hospital |

Prospective cohort |

18 months |

Maintenance |

PD |

315 |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Lowrie 1990 [50] |

National Medical Care |

Cross-sectional |

18 months |

Maintenance |

HD |

19,746 |

No |

Not measured |

Yes |

No |

No |

| Lukowski 2010 [51] |

DaVita |

Retrospective cohort |

3 years |

Maintenance |

HD |

58,917 |

Yes (for phosphorus only, Not stated for PTH and calcium) |

Not stated |

Yes |

Not stated |

Yes for phosphorus No for calcium or PTH |

| Maeda 2009 [52] |

Kyushu University Hospital |

Prospective cohort |

5 years |

Maintenance |

HD |

226 |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| McNeill 2010 [53] |

DaVita |

Cohort, unspecified |

3 years |

Maintenance |

HD |

58,917 |

Yes (for PTH only, Not stated for phosphorus and calcium) |

Yes |

Not stated |

Not stated |

Yes for PTH No for calcium or phosphorus |

| Melamed 2006 [54] |

CHOICE |

Prospective cohort |

2.5 years (median) |

Incident |

HD, PD |

1,007 |

Yes |

Yes (as a time-dependent predictor) |

Yes (as a time-dependent predictor) |

Yes (as a time-dependent predictor) |

No |

| Miller 2010 [22] |

DaVita-Los Angeles |

Retrospective cohort |

5 years |

Maintenance |

HD |

107,200 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes for calcium No for phosphorus or PTH |

| Miller 2009 [55] |

DaVita |

Cohort, unspecified |

5 years |

Maintenance |

HD |

151,555 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Morrone 2009 [56] |

MMTE (Italy) |

Prospective cohort |

18.8 months (mean) |

Incident |

HD |

411 |

Yes |

Yes |

Not stated |

Not stated |

Yes for PTH No for phosphorus or calcium |

| Naves-Diaz 2011 [57] |

Fresenius-CORES |

Retrospective cohort |

4.5 years |

Incident or Maintenance |

HD |

16,173 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Naves-Diaz 2008 [58] |

Fresenius-CORES |

Retrospective cohort |

4.5 years |

Incident or Maintenance |

HD |

16,004 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Noordzij 2008 [26] |

NECOSAD |

Prospective cohort |

7.8 years |

Incident |

HD, PD |

1,621 |

Yes (restricted cubic splines) |

Not stated |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes (spline) |

| Noordzij 2005 [23] |

NECOSAD |

Prospective cohort |

7.5 years (max) |

Incident |

HD, PD |

1,629 |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

| Phelan 2008 [59] |

Beaumon Hospital (Ireland) |

Retrospective cohort |

4.5 years (mean) |

Incident |

HD, PD |

1,007 |

Yes (binary only) |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

| Port 2004 [60] |

DOPPS I |

Prospective cohort |

5 years |

Maintenance |

HD |

17,245 |

Yes (for phosphorus only, binary) |

Not measured |

Yes |

Not measured |

No |

| Saran 2003 [61] |

DOPPS |

Retrospective cohort |

1.8-2.9 years (median, depending on region) |

Maintenance |

HD |

14,930 |

Yes (for phosphorus only, binary) |

No |

Yes |

Not measured |

No |

| Shinaberger 2008 [20] |

DaVita |

Retrospective cohort |

3 years |

Maintenance |

HD |

30,075 |

Yes (restricted cubic splines) |

Not stated |

Yes |

Not stated |

Yes |

| Shinaberger 2008 [21] |

DaVita |

Retrospective cohort |

3 years |

Maintenance |

HD |

34,307 |

Yes (restricted cubic splines, PTH only) |

Yes |

Not stated |

Not stated |

Yes |

| Simic-Ogrizovic 2009 [62] |

Clinical Center of Serbia |

Prospective cohort |

3 years |

Maintenance |

HD |

130 |

No |

Not measured |

Yes |

No |

No |

| Sit 2008 [63] |

Dicle University |

Retrospective cohort |

10 years |

Maintenance |

NR |

1,538 |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

| Slinin 2005 [5] |

USRDS (1/2/3) |

Retrospective cohort |

3.9 years (mean) |

Maintenance |

HD |

14,829 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Stevens 2004 [25] |

PROMIS |

Prospective cohort |

2.6 years (median) |

Maintenance |

HD, PD |

515 |

Yes (examined interactions; also modeled continuous, linear predictors) |

No, when continuous Yes, when categorical with interactions |

Yes, for both continuous and categorical with interactions |

No, when continuous Yes, when categorical with interactions |

No |

| Takemoto 2009 [64] |

Toranomon Hospital |

Prospective cohort |

8 years |

Maintenance |

HD |

68 |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

| Wald 2008 [65] |

HEMO |

Post-hoc RCT |

6.5 years |

Maintenance |

HD |

1,846 |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes for calcium and phosphorus No for PTH |

| Young 2004 [66] | DOPPS 1/2 | Retrospective cohort | 2 years | Maintenance | HD | 15,475 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

HD, hemodialysis; NR, not reported; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PTH, parathyroid hormone; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

* Study explicitly allowed for a non-linear relationship between biochemical parameters and mortality (eg, use of a categorical variable or splines).

†Study provided a graphical depiction of the relationship between biochemical parameters and mortality.

As noted in Table 1, most studies found a significant relationship between the 3 biochemical measures and mortality. Twelve studies (23.5%) modeled the biochemical measures as linear, continuous variables. Furthermore, no paper included explicit discussion of testing for non-linearity to justify this decision. Another 14 studies (27.5%) attempted to model these variables in a non-linear manner but only did so for some measures (eg, just phosphorus) or merely dichotomized the variable rather than use multiple categories or splines. Only 5 of 51 studies used spline functions even though this is the most rigorous method to handle non-linearity and prevents a loss of power compared to categorization [67].

The choice of a linear or non-linear model also affected results. In 8 studies that measured PTH and modeled it linearly, 4 (50.0%) found no significant association with mortality. In contrast, in the 37 studies that modeled PTH with categories or splines, just 8 (21.6%) found no significant association. For phosphorus, 5 of 11 studies with linear models (45.5%) found no association with mortality compared to 2 of 37 studies (5.4%) in which phosphorus was modeled as a non-linear predictor. Similarly for calcium, 4 of 10 studies with linear models (40.0%) explicitly stated no association with mortality compared to 2 of 37 non-linear studies (5.4%). Nineteen of 51 studies graphed at least one categorized predictor (eg, by quartile) by either percent dying or by adjusted RR. In 18 of 19 studies (94.7%), a non-linear U or J shape was evident for at least one of these variables.

Primary meta-analysis findings

Seven studies were included in the meta-analysis (see Table 2) because the majority of candidate reports did not contain the necessary data elements. Of the 7 studies, 4 included relevant data on phosphorus [10,14,24,30], 3 on calcium [10,14,30], and 5 on PTH [14-16,29,30]. Although we made no restrictions based on study design or dialysis type, all of the included studies were prospective or retrospective cohort studies, and virtually all patients received hemodialysis.

Table 2.

Summary of studies included in meta-analysis

| Author, year | Study or database name | Study design | Duration of follow-up | Dialysis vintage | Dialysis type | Sample size | Biochemical parameters with adequate data | Timing of assessment | Model adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block, 2004 [10] |

Fresenius Medical Care |

Retrospective cohort |

12-18 months (total) |

Maintenance |

HD |

40,538 |

P, Ca |

Average of values in first 3 months of study |

Multivariate adjusted |

| Dukkipati, 2010 [29] |

DaVita-NIED |

Prospective cohort |

63 months (total) |

Maintenance |

HD |

748 |

PTH |

Baseline, drawn prior to dialysis session |

Multivariate (MICS) adjusted |

| Floege, 2011 [16] |

European Fresenius Medical Care |

Retrospective cohort |

20.9 months (median) |

Incident, 35% Maintenance, 65% |

HD |

7,970 |

PTH |

Average of values in 1st quarter of follow-up |

Multivariate, time-dependent adjusted |

| Kalantar-Zadeh, 2006 [14] |

DaVita |

Prospective cohort |

24 months (total) |

Maintenance |

HD |

58,058 |

P, Ca, PTH |

Average of values in 1st quarter of follow-up |

Multivariate (MICS), time-dependent adjusted |

| Rodriguez-Benot, 2005 [24] |

Cordoba, Spain |

Prospective cohort |

97.6 months (median) |

Maintenance |

HD |

385 |

P |

6-month mean prior to death or end of study period |

Multivariate adjusted |

| Tangri, 2011 [30] |

UKRR |

Prospective cohort |

24 months (total) |

Incident |

HD, 70% PD, 30% |

7,076 |

P, Ca, PTH |

Average of values during the first year of dialysis |

Multivariate adjusted |

| Tentori, 2008 [15] | Dialysis Clinic Inc. | Prospective cohort | 16.4 months (median) | Maintenance | HD | 25,588 | PTH* | Baseline | Multivariate adjusted |

Ca, calcium; HD, hemodialysis; MICS, malnutrition-inflammation complex syndrome; NIED, Nutritional and Inflammatory Evaluation in Dialysis; P, phosphorus; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PTH, parathyroid hormone; UKRR, United Kingdom Renal Registry.

*Excluded data for the other biochemical parameters due to discrepancies between sample sizes presented in publication tables and manuscript text.

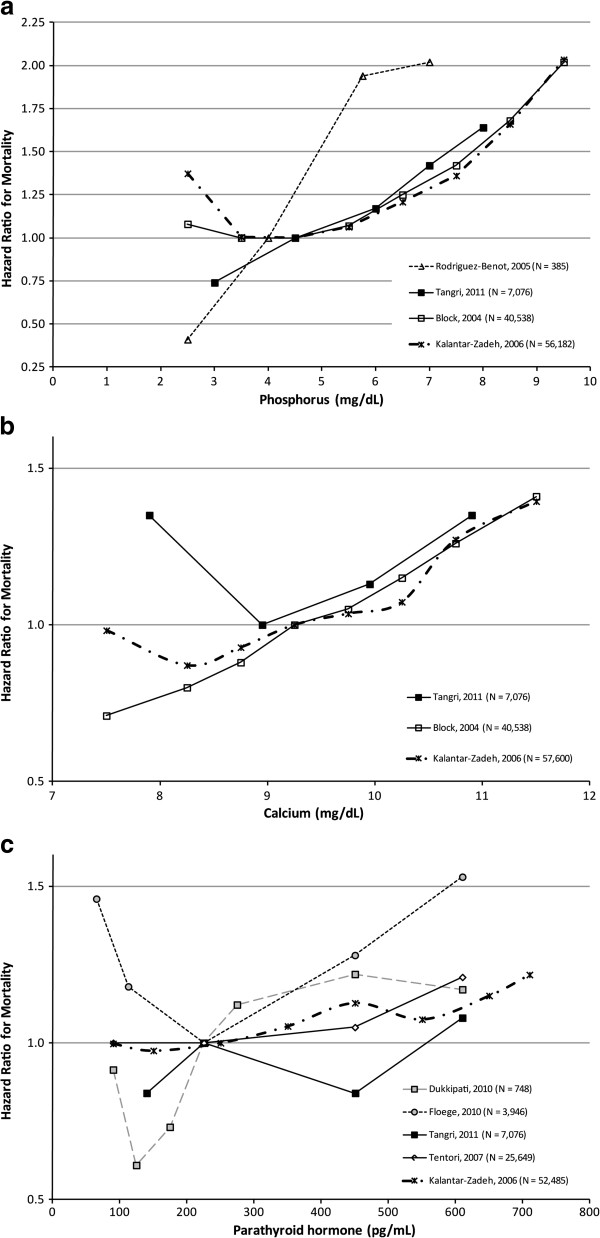

Reference ranges were generally consistent across studies. The midpoints of the reference ranges were ≈4-4.5 mg/dL for phosphorus (with the exception of Kalantar-Zadeh 2006 [14], which was 5.5 mg/dL), ≈9-9.25 mg/dL for calcium, and ≈225-250 pg/mL for PTH (with the exception of Dukkipati 2010 [29], which was 450 pg/mL). Figures 3a-c provide graphical depictions of the HRs from the studies used in each meta-analysis.

Figure 3.

Studies used in the meta-analysis of biochemical parameters and mortality. In these studies, biochemical parameter levels were analyzed as categorical variables. In order to visualize the relationship between mortality and the biochemical parameters, the values on the x-axis for each symbol in the figure represent the midpoint within each category for each study. In order to make the graphical representation more comparable across studies, we adjusted the HRs so that the midpoint of the reference range was as similar as possible. We stress that this is done just for the figures only and not for the meta-analyses. Specific adjustments are noted below.a. Phosphorus: The midpoints of reference ranges were ≈4- 4.5 mg/dL across all studies with the exception of Kalantar-Zadeh 2006 [14]. For this study, we adjusted the graphical depiction of the reference range from 5–6 mg/dL to 4–5 mg/dL. Of note, non-linear relationships were most clearly evident in the 2 studies with the largest sample sizes. b. Calcium: The midpoints of reference ranges were ≈9-9.25 mg/dL across all studies. No studies had to be adjusted for graphical display. c. PTH: The midpoints of reference ranges were ≈225-250 pg/mL across all studies with the exception of Dukkipati 2010 [29]. For this study, we adjusted the graphical depiction of the reference range from 300–600 pg/mL to 200–249 pg/mL.

We present the adjusted RRs based on the Hamling method for each study in Table 3 (relatively high values versus referent) and Table 4 (relatively low versus referent). Table 5 summarizes the derived RRs from each meta-analysis. Higher-than-referent levels of phosphorus (RR = 1.20, 95% CI=1.15-1.25), calcium (RR = 1.10, 95% CI=1.05-1.14), and PTH (RR = 1.11, 95% CI=1.07-1.16) were all significantly associated with an increased risk of mortality. Although no significant associations between relatively low phosphorus or PTH and mortality were observed, there did appear to be a protective effect for relatively low calcium and mortality (RR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.83-0.89).

Table 3.

Mortality risk for relatively high biochemical parameter values versus referent values

| Study | Reference range | N* | RR for high values vs. referent (95% CI) | Follow-up (months)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Phosphorus (mg/dL) | ||||

| Block 2004 [10] |

4.0-5.0 |

35,783 |

1.21 (1.14-1.29) |

18 |

| Kalantar-Zadeh 2006 [14] |

5.0-6.0 |

36,955 |

1.20 (1.13-1.29) |

24 |

| Rodriguez-Benot 2005 [24] |

3.0-5.0 |

375 |

1.96 (1.20-3.18) |

97.6 |

| Tangri 2010 [30] |

3.5-5.5 |

6,538 |

0.74 (0.53-1.03) |

24 |

|

Calcium (mg/dL) | ||||

| Block 2004 [10] |

9.0-9.5 |

23,168 |

1.14 (1.06-1.22) |

30 |

| Kalantar-Zadeh 2006 [14] |

9.0-9.5 |

36,831 |

1.06 (1.00-1.12) |

24 |

| Tangri 2010 [30] |

8.4-9.5 |

6,843 |

1.23 (0.95-1.58) |

24 |

|

Parathyroid hormone (pg/mL) | ||||

| Dukkipati 2010 [29] |

300-600 |

288 |

0.96 (0.60-1.55) |

63 |

| Floege 2010 [16] |

150-300 |

2,443 |

1.35 (1.14-1.61) |

20.9 |

| Kalantar-Zadeh 2006 [14] |

200-300 |

29,273 |

1.12 (1.06-1.18) |

24 |

| Tangri 2010 [30] |

151-300 |

4,842 |

0.92 (0.71-1.20) |

24 |

| Tentori 2008 [15] | 100-300 | 18,224 | 1.09 (1.02-1.16) | 18.7 |

CI, confidence interval; RR, risk ratio.

*Sample size includes patients in the reference range plus those with relatively high biochemical parameter values.

†The median or mean (or total, if median was not given) follow-up time in each study.

Table 4.

Mortality risk for relatively low biochemical parameter values versus referent values

| Study | Reference range | N* | RR for low values vs. referent (95% CI) | Follow-up (months)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Phosphorus (mg/dL) | ||||

| Block 2004 [10] |

4.0-5.0 |

13,478 |

1.01 (0.95-1.08) |

18 |

| Kalantar-Zadeh 2006 [14] |

5.0-6.0 |

34,636 |

0.99 (0.88-1.12) |

24 |

| Rodriguez-Benot 2005 [24] |

3.0-5.0 |

170 |

0.41 (0.05-3.26) |

97.6 |

| Tangri 2011 [30] |

3.5-5.5 |

4,776 |

1.22 (1.01-1.49) |

24 |

|

Calcium (mg/dL) | ||||

| Block 2004 [10] |

9.0-9.5 |

28,129 |

0.81 (0.77-0.85) |

30 |

| Kalantar-Zadeh 2006 [14] |

9.0-9.5 |

37,662 |

0.93 (0.87-0.98) |

24 |

| Tangri 2011 [30] |

8.4-9.5 |

3,394 |

1.35 (0.24-7.48) |

24 |

|

Parathyroid hormone (pg/mL) | ||||

| Dukkipati 2010 [29] |

300-600 |

648 |

0.72 (0.52-0.95) |

63 |

| Floege 2010 [16] |

150-300 |

2,595 |

1.31 (1.14-1.51) |

20.9 |

| Kalantar-Zadeh 2006 [14] |

200-300 |

33,758 |

0.99 (0.94-1.05) |

24 |

| Tangri 2011 [30] |

151-300 |

5,071 |

0.84 (0.61-1.16) |

24 |

| Tentori 2008 [15] | 100-300 | 17,648 | 1.00 (0.93-1.08) | 18.7 |

CI, confidence interval; RR, risk ratio.

*Sample size includes patients in the reference range plus those with relatively low biochemical parameter values.

†The median or mean (or total, if median was not given) follow-up time in each study.

Table 5.

Summary of findings: meta-analyses of mortality risk for relatively high/low biochemical parameter values versus referent values*

| Biochemical parameter |

Mortality risk for relatively low biochemical parameter values |

Mortality risk for relatively high biochemical parameter values |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk ratio (95% CI) | I2 | Risk ratio (95% CI) | I2 | |

|

Phosphorus |

1.02 (0.97-1.08) |

30.5% |

1.20 (1.15-1.25) |

75.2% |

|

Calcium |

0.86 (0.83-0.89) |

84.0% |

1.10 (1.05-1.14) |

39.9% |

| PTH | 1.01 (0.97-1.05) | 79.8% | 1.11 (1.07-1.16) | 47.8% |

*Statistical heterogeneity: the I2 statistic describes the percent of variation in the risk ratio that is attributable to heterogeneity in a meta-analysis.

We conducted 6 meta-regressions to examine the effect of follow-up time on the RR estimates, one for each biochemical parameter at relatively low and high values. Results from the meta-regression indicated that follow-up time did not have a statistically significant effect on the RRs (data not shown).

Sensitivity analysis

We varied the baseline estimated number of deaths and non-deaths in the referent group when doing the Hamling analysis by 10% to 15% in both directions. Results of these sensitivity analyses demonstrated that the estimated RR values were extremely stable and almost identical to the original estimates (data not shown). Due to the dissimilar reference range used by Dukkipati, we also re-ran the original meta-analyses without this study. The overall effect estimates and measures of heterogeneity were not appreciably different from those in the primary analysis (data not shown).

Simulation analysis

Preliminary work on a simulation of 5 large observational studies (Block et al. [10], Floege et al. [16], Kalantar-Zadeh et al. [14], Slinin et al. [5], and Tentori et al. [15]), in which we estimated continuous functions for the relationship between mortality and each of the 3 biochemical parameters also showed non-linear U- or J-shaped trends that were a good fit with the published data. Similar to the meta-analysis, the simulation showed significant heterogeneity among the studies for all 3 biochemical parameters. The source of the heterogeneity was not obvious.

Discussion

Our literature review shows that most studies found a significant relationship between serum levels of PTH, calcium, and phosphorus and mortality even though a sizeable number naively modeled these variables as linear predictors. Another large group of studies only examined these variables as binary variables, which is a methodologically weak approach. For example, Phelan et al. [59] found no relationship between PTH above and below 300 pg/ml and mortality. Interestingly, they correctly deduced that this result may be because very high PTH values could have “cancelled out” very low PTH values and both extremes may be harmful. However, they did not take corrective actions (eg, more categories, spline functions) in their methods. We also rarely encountered a paper that reported explicit power calculations, which is important given that categorizing a variable reduces power. Thus, it is important to acknowledge that the statistical methods used in the literature may be insufficient and the results should be cautiously interpreted.

In our meta-analysis, higher-than-referent (often “normal”) serum levels of PTH, calcium, and phosphorus in dialysis patients were positively associated with increased mortality. For lower-than-referent values, findings were less consistent across the 3 selected parameters; we observed no significant association for phosphorus and PTH and reduced mortality for relatively low values of calcium. The correlation between increased mortality and elevated biochemical parameter values was expected based on the assumption that levels within a “normal” range represent optimal health. The lack of statistical significance for lower values of phosphorus and PTH may be partly attributable to the small numbers of dialysis patients with sub-referent levels, leading to low statistical power. Although low serum calcium is not typically considered “healthy,” the association with significantly lower mortality risk is not completely surprising and may be explained by lower vascular calcification and associated mortality [10,68-72].

Although our findings for phosphorus and mortality are in line with those of the recent meta-analysis by Palmer et al. [18], our findings for calcium and PTH differ as Palmer et al. did not demonstrate a significant mortality risk for either calcium or PTH. There are several reasons for this disparity. First, the Palmer study assumed a linear relationship between the biochemical parameters and mortality over the total range of values, while our study used a piecewise linear approach that allowed for the possibility of U-shaped or J-shaped relationships. As Figure 1 illustrates, if the relationship is U-shaped or J-shaped, a linear assumption may incorrectly estimate the magnitude of the association. In fact, when studies did model a biochemical parameter as both a continuous, linear predictor and then as a categorical variable, the RRs were more extreme with the categorical approach [45,47]. The Palmer study also included studies of patients who were not on dialysis, such as patients with pre-dialysis CKD and ESRD patients who had received kidney transplants. If the relationship between abnormal biochemical parameters and mortality is strongest among the sickest patients (ie, those on dialysis), this would further attenuate the estimated relationship. Furthermore, some studies that were included in Palmer’s meta-analysis could not be utilized with our meta-analytic approach as our requirements for analysis were more stringent.

Using very similar review methods to ours, Covic et al. [17] concluded that quantitative synthesis in a meta-analysis was not possible due to significant clinical and methodological heterogeneity across the identified studies. Although we attempted to resolve this by including additional, more recent studies and by focusing on a more clinically narrow population of ESRD patients, we still observed clinical and methodological heterogeneity in the included studies. Aside from the types of differences documented by Covic et al. [17], including variations for dialysis vintage and covariates included in the respective multivariate models, we theorize that the clinical context of these studies may be an important source of heterogeneity. For example, management of biochemical abnormalities and/or other aspects of patient care may vary across institutions or according to geographic region (eg, vitamin D use). It is worth noting that most studies found a significant association with all 3 variables and mortality and when the variables were graphed against mortality, frequently a U or J shape was observed.

Our meta-analysis has specific limitations. Although we did not perform independent, dual data abstraction (the gold standard for systematic reviews), we employed a rigorous quality review of abstracted data, and we do not believe that this approach compromised the accuracy of our results. Additionally, while several statistically significant associations between biochemical parameters and mortality were found, we stress that association alone does not necessitate a causal relationship. For example, relatively high values of any of the 3 biochemical parameters may reflect the general health of a patient, which may not change as a result of treatment geared to normalizing a single abnormality. Furthermore, many patients in these observational studies received medications aimed at correcting (or preventing) out-of-range levels; their ability to respond to such therapies may have reflected their general health.

In addition, we excluded several large studies because their results could not be synthesized in our meta-analysis due to the way the results were reported. All meta-analyses are limited by the availability of pertinent data in relevant publications, and the study by Palmer et al. also excluded many studies for a variety of reasons. Nevertheless, our analysis of abnormally low values may have been underpowered and we encourage future studies to look at this clinically uncommon subset of patients in more detail.

Our study analyzed the association between biochemical parameter values above and below the referent value of a study in order to better approximate non-linearity, although this approach still assumes linear relationships above and below the reference range. However, not all studies used a reference range that would be expected to include the nadir of the curve, which leads to a lower-than-expected slope estimate for the segment of the curve that includes the nadir of the U-shape or J-shape. This underestimation is similar to that due to assuming a linear effect, although the magnitude of bias is much smaller. The 2 studies [14,29] that chose a reference range outside of “normal” bounds both used values that were higher than the other studies with which they were meta-analyzed; this may have led to an underestimation of the effect of relatively low values.

Finally, the historical approach to altered mineral metabolism has been somewhat reductionist as studies tend to evaluate individual biochemical parameters in isolation and assume independence across those parameters. Unfortunately, a more comprehensive approach that explores the interactions between biochemical parameters for mortality effects has not been well researched [25]. While some studies reported data on calcium-phosphorus product, not all investigated the extent to which their results showed interaction between calcium and phosphorus, and the main effects of calcium and phosphorus were not always reported, which is a major methodological shortcoming. Therefore, our meta-analysis did not consider interactions. The lack of investigation of interactions further hinders direct applicability of the results of observational studies to determine the quantitative targets of practice guidelines.

Conclusions

In summary, we conclude that the relationships between phosphorus, calcium, and PTH and mortality among ESRD patients receiving dialysis appear to not be linear but rather trend towards non-linear U-shaped or J-shaped curves. In addition, we found that elevated values of all 3 of these biochemical parameters were associated with increased mortality. Also, our literature review shows that many studies have naively modeled the relationship between these biochemical markers and mortality making their interpretation problematic at best. Prior meta-analyses of studies that have not correctly modeled these biochemical markers cannot be considered definitive. Instead, we suggest that future studies use more advanced modeling techniques (eg, spline terms, interactions) on large datasets in order to better describe possible non-linear relationships between the biochemical markers and mortality.

Competing interests

This study was supported by Amgen Inc. Authors SC, WG, and VB are all employees and stockholders in Amgen Inc.

Author’s contributions

JN was responsible for the design and conduct of the systematic review, design of meta-analysis, interpretation of results, and composition of all sections of the manuscript. RB was responsible for the design of the meta-analysis, interpretation of results, composition of the Discussion section, and review of the manuscript. BN was responsible for the design and conduct of the meta-analysis, interpretation of results, and composition of all sections of the manuscript. RM was responsible for the design of the systematic review, interpretation of results, and review of the manuscript. SC, WG, and VB are all employees and stockholders in Amgen Inc and each contributed to the interpretation of results, writing and review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

Search Strategy (adapted from Covic et al. conducted on December 5, 2010). Note: The search strategy was created in PubMed and adapted as necessary for Embase and Cochrane.

Contributor Information

Jaime L Natoli, Email: jaime.natoli@hotmail.com.

Rob Boer, Email: dutchrob@Yahoo.com.

Brian H Nathanson, Email: brian.h.nathanson@att.net.

Ross M Miller, Email: Ross.Miller@Cerner.com.

Silvia Chiroli, Email: schiroli@amgen.com.

William G Goodman, Email: wgoodman@amgen.com.

Vasily Belozeroff, Email: vasilyb@amgen.com.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Geoffrey A. Block, MD, for his valuable input on early drafts of this manuscript and Holly Tomlin, MPH (employee and stockholder, Amgen Inc.) and Lisa Kaspin, PhD (employee and stockholder, Cerner Research) for editing and journal formatting assistance.

References

- Owda A, Elhwairis H, Narra S, Towery H, Osama S. Secondary hyperparathyroidism in chronic hemodialysis patients: prevalence and race. Ren Fail. 2003;25:595–602. doi: 10.1081/JDI-120022551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatopolsky E, Brown A, Dusso A. Pathogenesis of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Kidney Int Suppl. 1999;73:S14–S19. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.07304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ. Clinical epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:S112–S119. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9820470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley RN, Parfrey PS. Cardiovascular disease and mortality in ESRD. J Nephrol. 1998;11:239–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slinin Y, Foley RN, Collins AJ. Calcium, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone, and cardiovascular disease in hemodialysis patients: the USRDS waves 1, 3, and 4 study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1788–1793. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004040275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suliman ME, Qureshi AR, Barany P, Stenvinkel P, Filho JC, Anderstam B, Heimburger O, Lindholm B, Bergstrom J. Hyperhomocysteinemia, nutritional status, and cardiovascular disease in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2000;57:1727–1735. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh SK, Stack AG, Levin NW, Hulbert-Shearon T, Port FK. Association of elevated serum PO(4), Ca x PO(4) product, and parathyroid hormone with cardiac mortality risk in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:2131–2138. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12102131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco MP, Craver L, Betriu A, Belart M, Fibla J, Fernandez E. Higher impact of mineral metabolism on cardiovascular mortality in a European hemodialysis population. Kidney Int Suppl. 2003;85:S111–S114. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.63.s85.26.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young EW, Albert JM, Satayathum S, Goodkin DA, Pisoni RL, Akiba T, Akizawa T, Kurokawa K, Bommer J, Piera L, Port FK. Predictors and consequences of altered mineral metabolism: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1179–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block GA, Klassen PS, Lazarus JM, Ofsthun N, Lowrie EG, Chertow GM. Mineral metabolism, mortality, and morbidity in maintenance hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2208–2218. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000133041.27682.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Francisco AL. Secondary hyperparathyroidism: review of the disease and its treatment. Clin Ther. 2004;26:1976–1993. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blayney MJ, Pisoni RL, Bragg-Gresham JL, Bommer J, Piera L, Saito A, Akiba T, Keen ML, Young EW, Port FK. High alkaline phosphatase levels in hemodialysis patients are associated with higher risk of hospitalization and death. Kidney Int. 2008;74:655–663. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avram MM, Mittman N, Myint MM, Fein P. Importance of low serum intact parathyroid hormone as a predictor of mortality in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients: 14 years of prospective observation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:1351–1357. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.29254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kuwae N, Regidor DL, Kovesdy CP, Kilpatrick RD, Shinaberger CS, McAllister CJ, Budoff MJ, Salusky IB, Kopple JD. Survival predictability of time-varying indicators of bone disease in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2006;70:771–780. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tentori F, Blayney MJ, Albert JM, Gillespie BW, Kerr PG, Bommer J, Young EW, Akizawa T, Akiba T, Pisoni RL, Robinson BM, Port FK. Mortality risk for dialysis patients with different levels of serum calcium, phosphorus, and PTH: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:519–530. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floege J, Kim J, Ireland E, Chazot C, Drueke T, de Francisco A, Kronenberg F, Marcelli D, Passlick-Deetjen J, Schernthaner G, Fouqueray B, Wheeler DC. Serum iPTH, calcium and phosphate, and the risk of mortality in a European haemodialysis population. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1948–1955. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covic A, Kothawala P, Bernal M, Robbins S, Chalian A, Goldsmith D. Systematic review of the evidence underlying the association between mineral metabolism disturbances and risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality and cardiovascular events in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:1506–1523. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer SC, Hayen A, Macaskill P, Pellegrini F, Craig JC, Elder GJ, Strippoli GF. Serum levels of phosphorus, parathyroid hormone, and calcium and risks of death and cardiovascular disease in individuals with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305:1119–1127. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham J, Silver J. CKD-MBD: comfort in the trough of the U. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1764–1766. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinaberger CS, Greenland S, Kopple JD, Van WD, Mehrotra R, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Is controlling phosphorus by decreasing dietary protein intake beneficial or harmful in persons with chronic kidney disease? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1511–1518. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinaberger CS, Kopple JD, Kovesdy CP, McAllister CJ, Van WD, Greenland S, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Ratio of paricalcitol dosage to serum parathyroid hormone level and survival in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1769–1776. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01760408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JE, Kovesdy CP, Norris KC, Mehrotra R, Nissenson AR, Kopple JD, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Association of cumulatively low or high serum calcium levels with mortality in long-term hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2010;32:403–413. doi: 10.1159/000319861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordzij M, Korevaar JC, Boeschoten EW, Dekker FW, Bos WJ, Krediet RT. The Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) Guideline for Bone Metabolism and Disease in CKD: association with mortality in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:925–932. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Benot A, Martin-Malo A, Alvarez-Lara MA, Rodriguez M, Aljama P. Mild hyperphosphatemia and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:68–77. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens LA, Djurdjev O, Cardew S, Cameron EC, Levin A. Calcium, phosphate, and parathyroid hormone levels in combination and as a function of dialysis duration predict mortality: evidence for the complexity of the association between mineral metabolism and outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:770–779. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000113243.24155.2F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordzij M, Korevaar JC, Dekker FW, Boeschoten EW, Bos WJ, Krediet RT, Bossuyt PM, Geskus RB. Mineral metabolism and mortality in dialysis patients: a reassessment of the K/DOQI guideline. Blood Purif. 2008;26:231–237. doi: 10.1159/000118847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S, Longnecker MP. Methods for trend estimation from summarized dose–response data, with applications to meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:1301–1309. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamling J, Lee P, Weitkunat R, Ambuhl M. Facilitating meta-analyses by deriving relative effect and precision estimates for alternative comparisons from a set of estimates presented by exposure level or disease category. Stat Med. 2008;27:954–970. doi: 10.1002/sim.3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukkipati R, Kovesdy CP, Colman S, Budoff MJ, Nissenson AR, Sprague SM, Kopple JD, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Association of relatively low serum parathyroid hormone with malnutrition-inflammation complex and survival in maintenance hemodialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2010;20:243–254. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangri N, Wagner M, Griffith JL, Miskulin DC, Hodsman A, Ansell D, Naimark DM. Effect of Bone Mineral Guideline Target Achievement on Mortality in Incident Dialysis Patients: An Analysis of the United Kingdom Renal Registry. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57:415–421. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block GA, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Levin NW, Port FK. Association of serum phosphorus and calcium x phosphate product with mortality risk in chronic hemodialysis patients: a national study. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;31:607–617. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v31.pm9531176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block GA, Zaun D, Smits G, Persky M, Brillhart S, Nieman K, Liu J, St Peter WL. Cinacalcet hydrochloride treatment significantly improves all-cause and cardiovascular survival in a large cohort of hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2010;78:578–589. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JJ, Concato J, Wells CK, Crowley ST. Prognostic implications of clinical practice guidelines among hemodialysis patients. Hemodial Int. 2006;10:399–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2006.00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drechsler C, Grootendorst DC, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT, Wanner C, Dekker FW. Changes in parathyroid hormone, body mass index and the association with mortality in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1340–1346. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drechsler C, Verduijn M, Pilz S, Dekker FW, Krediet RT, Ritz E, Wanner C, Boeschoten EW, Brandenburg V. Vitamin D status and clinical outcomes in incident dialysis patients: results from the NECOSAD study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1024–1032. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter C, Straub Y, Hersberger M, Raz HR, Kistler T, Kiss D, Wuthrich RP, Gloor HJ, Aerne D, Wahl P, Klaghofer R, Ambuhl PM. Pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A is an independent short-time predictor of mortality in patients on maintenance haemodialysis. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:354–359. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Harnett JD, Kent GM, Hu L, O'Dea R, Murray DC, Barre PE. Hypocalcemia, morbidity, and mortality in end-stage renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 1996;16:386–393. doi: 10.1159/000169030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez OM, Mannstadt M, Isakova T, Rauh-Hain JA, Tamez H, Shah A, Smith K, Lee H, Thadhani R, Juppner H, Wolf M. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:584–592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakemi MS, Golbabaei M, Nassiri A, Kayedi M, Hosseini M, Atabak S, Ganji MR, Amini M, Saddadi F, Najafi I. Predictors of patient survival in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: 10-year experience in 2 major centers in Tehran. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2010;4:44–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao CH, Chao A, Chu SY, Lin KK, Yeung L, Lin-Tan DT, Lin JL. Association of severity of conjunctival and corneal calcification with all-cause 1-year mortality in maintenance haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1016–1023. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isakova T, Gutierrez OM, Chang Y, Shah A, Tamez H, Smith K, Thadhani R, Wolf M. Phosphorus binders and survival on hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:388–396. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008060609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jassal SV, Douglas JF, Stout RW. Prognostic markers in older patients starting renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:1052–1057. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a027455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean G, Terrat JC, Vanel T, Hurot JM, Lorriaux C, Mayor B, Chazot C. High levels of serum fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-23 are associated with increased mortality in long haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2792–2796. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalantar-Zadeh K, Miller JE, Kovesdy CP, Mehrotra R, Lukowsky LR, Streja E, Ricks J, Jing J, Nissenson AR, Greenland S, Norris KC. Impact of race on hyperparathyroidism, mineral disarrays, administered vitamin D mimetic, and survival in hemodialysis patients. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2448–2458. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimata N, Albert JM, Akiba T, Yamazaki S, Kawaguchi Y, Fukuhara S, Akizawa T, Saito A, Asano Y, Kurokawa K, Pisoni RL, Port FK. Association of mineral metabolism factors with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hemodialysis patients: the Japan dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study. Hemodial Int. 2007;11:340–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2007.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komaba H, Igaki N, Takashima M, Goto S, Yokota K, Komada H, Takemoto T, Kohno M, Kadoguchi H, Hirosue Y, Goto T. Calcium, phosphorus, cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in hemodialysis patients: a single-center retrospective cohort study to reassess the validity of the Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy guidelines. Ther Apher Dial. 2008;12:42–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2007.00539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacson E Jr, Wang W, Hakim RM, Teng M, Lazarus JM. Associates of mortality and hospitalization in hemodialysis: potentially actionable laboratory variables and vascular access. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:79–90. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggat JE Jr, Orzol SM, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Golper TA, Jones CA, Held PJ, Port FK. Noncompliance in hemodialysis: predictors and survival analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:139–145. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9669435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JL, Lin-Tan DT, Chen KH, Hsu CW, Yen TH, Huang WH, Huang YL. Blood lead levels association with 18-month all-cause mortality in patients with chronic peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:1627–1633. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowrie EG, Lew NL. Death risk in hemodialysis patients: the predictive value of commonly measured variables and an evaluation of death rate differences between facilities. Am J Kidney Dis. 1990;15:458–482. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)70364-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukowsky L, Kovesdy CP, McNeill G, Streja E, Jing J, Krishnan M, Nissenson AR, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Comparing mortality-predictability of hyperphosphatemia in maintenance hemodialysis patients with and without Polycystic Kidney Disease (PKD) Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:A76. [Google Scholar]

- Maeda S, Sawayama Y, Furusyo N, Shigematsu M, Hayashi J. The association between fatal vascular events and risk factors for carotid atherosclerosis in patients on maintenance hemodialysis: plaque number of dialytic atherosclerosis study. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204:549–555. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill G, Streja E, Lukowsky L, Kovesdy CP, Jing J, Krishnan M, Nissenson AR, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Secondary hyperparathyroidism & survival in hemodialysis patients with & without polycystic kidney. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:A79. [Google Scholar]

- Melamed ML, Eustace JA, Plantinga L, Jaar BG, Fink NE, Coresh J, Klag MJ, Powe NR. Changes in serum calcium, phosphate, and PTH and the risk of death in incident dialysis patients: a longitudinal study. Kidney Int. 2006;70:351–357. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JE, Streja E, Kovesdy CP, Wyck DV, Nissenson AR, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Mortality of 5-Year time-averaged low serum calcium <8.5 mg/dL in subgroups of hemodialysis (HD) patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:A55. [Google Scholar]

- Morrone LF, Mazzaferro S, Russo D, Aucella F, Cozzolino M, Facchini MG, Galfre A, Malberti F, Mereu MC, Nordio M, Pertosa G, Santoro D. Interaction between parathyroid hormone and the Charlson comorbidity index on survival of incident haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2859–2865. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naves-Diaz M, Passlick-Deetjen J, Guinsburg A, Marelli C, Fernandez-Martin JL, Rodriguez-Puyol D, Cannata-Andia JB. Calcium, phosphorus, PTH and death rates in a large sample of dialysis patients from Latin America. The CORES Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1938–1947. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naves-Diaz M, Varez-Hernandez D, Passlick-Deetjen J, Guinsburg A, Marelli C, Rodriguez-Puyol D, Cannata-Andia JB. Oral active vitamin D is associated with improved survival in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2008;74:1070–1078. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan PJ, O'Kelly P, Walshe JJ, Conlon PJ. The importance of serum albumin and phosphorous as predictors of mortality in ESRD patients. Ren Fail. 2008;30:423–429. doi: 10.1080/08860220801964236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Port FK, Pisoni RL, Bragg-Gresham JL, Satayathum SS, Young EW, Wolfe RA, Held PJ. DOPPS estimates of patient life years attributable to modifiable hemodialysis practices in the United States. Blood Purif. 2004;22:175–180. doi: 10.1159/000074938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saran R, Bragg-Gresham JL, Rayner HC, Goodkin DA, Keen ML, Van Dijk PC, Kurokawa K, Piera L, Saito A, Fukuhara S, Young EW, Held PJ, Port FK. Nonadherence in hemodialysis: associations with mortality, hospitalization, and practice patterns in the DOPPS. Kidney Int. 2003;64:254–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simic-Ogrizovic S, Dopsaj V, Bogavac-Stanojevic N, Obradovic I, Stosovic M, Radovic M. Serum amyloid-A rather than C-reactive protein is a better predictor of mortality in hemodialysis patients. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2009;219:121–127. doi: 10.1620/tjem.219.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sit D, Kadiroglu AK, Kayabasi H, Kara IH, Yilmaz Z, Yilmaz ME. The evaluation incidence and risk factors of mortality among patients with end stage renal disease in Southeast Turkey. Ren Fail. 2008;30:37–44. doi: 10.1080/08860220701741965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemoto F, Katori H, Sawa N, Hoshino J, Suwabe T, Nakanishi S, Arai S, Fukuda S, Kodaka K, Shimada M, Yamazaki C, Yokoyama K, Nakano Y, Funahashi T, Ubara Y, Yamada A, Takaichi K, Uchida S. Plasma adiponectin: a predictor of coronary heart disease in hemodialysis patients–a Japanese prospective eight-year study. Nephron Clin Pract. 2009;111:c12–c20. doi: 10.1159/000178818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald R, Sarnak MJ, Tighiouart H, Cheung AK, Levey AS, Eknoyan G, Miskulin DC. Disordered mineral metabolism in hemodialysis patients: an analysis of cumulative effects in the Hemodialysis (HEMO) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:531–540. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young EW, Akiba T, Albert JM, McCarthy JT, Kerr PG, Mendelssohn DC, Jadoul M. Magnitude and impact of abnormal mineral metabolism in hemodialysis patients in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44:34–38. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ammirati AL, Dalboni MA, Cendoroglo M, Draibe SA, Santos RD, Miname M, Canziani ME. The progression and impact of vascular calcification in peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int. 2007;27:340–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fensterseifer DM, Karohl C, Schvartzman P, Costa CA, Veronese FJ. Coronary calcification and its association with mortality in haemodialysis patients. Nephrology (Carlton) 2009;14:164–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka M, Iseki K, Tamashiro M, Fujimoto N, Higa N, Touma T, Takishita S. Impact of high coronary artery calcification score (CACS) on survival in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2004;8:54–58. doi: 10.1007/s10157-003-0260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shantouf RS, Budoff MJ, Ahmadi N, Ghaffari A, Flores F, Gopal A, Noori N, Jing J, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Total and individual coronary artery calcium scores as independent predictors of mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2010;31:419–425. doi: 10.1159/000294405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigrist MK, Taal MW, Bungay P, McIntyre CW. Progressive vascular calcification over 2 years is associated with arterial stiffening and increased mortality in patients with stages 4 and 5 chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:1241–1248. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02190507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Search Strategy (adapted from Covic et al. conducted on December 5, 2010). Note: The search strategy was created in PubMed and adapted as necessary for Embase and Cochrane.