Abstract

Background

It is well established that there is a reduction in the skin blood flow (SBF) in response to heat with age and diabetes. While it is known that high BMI creates a stress on the cardiovascular system and increases the risk of all cause of morbidity and mortality, little is known of the effect of high BMI on SBF response to heat. Since diabetes is associated with age and a higher BMI, the interrelationship between age, BMI and SBF needs to be investigated to better understand the contribution diabetes alone has to endothelial impairment.

Material/Methods

This study examined the SBF to heat in young and old people with low and high BMI and people with diabetes with high BMI to determine the contribution these variables have on SBF. Subjects were ten young and older people with BMI <20 and ten young and older people with BMI >20 and ten subjects with diabetes with BMI >20. The SBF response, above the quadriceps, was determined during a 6 minutes exposure to heat at 44°C.

Results

Even in young people, SBF after the stress of heat exposure was reduced in subjects with a high BMI. The effect of BMI was greatest in young people and lowest in older people and people with diabetes; in people with diabetes, BMI was a more significant variable than diabetes in causing impairment of blood flow to heat. BMI, for example, was responsible for 49% of the reduction in blood flow after stress heat exposure (R=−0.7) while ageing only accounted for 16% of the blood flow reduction (R=−0.397).

Conclusions

These results would suggest the importance of keeping BMI low not only in people with diabetes to minimize further circulatory vascular damage, but also in young people to diminish long term circulatory vascular compromise.

Keywords: diabetes, cardiovascular, heat

Background

The use of heat for both therapeutic and preventive purposes dates back to 124 BC with the introduction by Asclepiads, a Greek physician [1]. Temperature is sensed in blood vessels through the TRP receptors and transient receptor potential channels, or TRP channels, are responsible for managing the body’s response to various stimuli, such as change in temperature [2–6]. One type of TRP channel is the TRPV channel, in which the V stands for vanilloid [6–10]. All TRPV1–4 channels are non-selective cation channels, moderately permeable to calcium, and are temperature sensitive [6,10–15].

TRPV1 was first isolated and named in 1997 as a capsaicin receptor [16–18]. It has been found that TRPV1 is found in greatest number in sensory neurons. TRPV1 is a heat sensor, and is activated by heat, specifically temperatures >42°C [16,18–20]. TRPV4 is expressed in epidermal keratinocytes [15]. While TRPV4 can be activated by warmth, it can also be activated by hypo-osmolarity [18,21–23].

The mechanism of the response of heat is two-fold. When skin is exposed to a temperature above 42°C, there is an immediate increase in circulation, controlled by sensory nerves in the skin [24–26]. This is mediated by TRPV1 calcium channels increasing calcium permeability, which then causes neuropeptides to be released, resulting in vasodilatation from the relaxation of smooth muscle [27–29]. This vasodilatation occurs to protect the skin in the event of a rapid change in temperature that may damage the skin [30–32]. Prolonged vasodilatation with exposure to heat occurs due to the influx of calcium and activation of nitric oxide synthetase mediated by TRPV4 channels on vascular endothelial cells [24–26].

The blood flow response to heat is impaired with ageing and diabetes [33–35]. While this is well documented, much less is known about the blood flow response to free radicals. When the free radical concentration reaches a critical level, rather than increasing blood flow, they biodegrade nitric oxide and prostacyclin, a second vasodilator released from vascular endothelial cells, into inactive forms [36–38]. In the presence of free radicals such as hydrogen peroxide, nitric oxide is reduced to peroxynitrite (ONOO), a free radical with no influence on circulation [39]. Bioconversion of nitric oxide to peroxynitrite is believed to be one of the mechanisms associated with the reduction in circulation at rest and during stress in older people and people with diabetes and leads to endothelial dysfunction [39]. In a recent study, free radicals were elevated in Asians after a single high fat meal. This resulted in a diminished blood flow response to heat [40,41]. Free radicals are also very high in people who are overweight [42,43]. If BMI itself limits the blood flow response to stress such as heat due to high free radicals in the body, and most people with diabetes have a high BMI, some of the damage from diabetes to circulation may be due to the BMI and not diabetes itself. The purpose of the present investigation was to test the hypothesis that high BMI in itself in addition to age are the main elements causing reduced blood flow in people with diabetes. Young and old subjects with low and high BMI were examined and their response to heat was measured. These data were used to establish a multifactor regression equation to predict what blood flow should be in people with diabetes based on their age and BMI. By comparing this to the actual blood flow response to heat, the reduction in blood flow due to diabetes alone could be calculated vs. BMI and age.

Material and Methods

Participants in this study were divided into 5 groups. Fifty male and female subjects participated. Ten young people age 18–34 with BMI less than 20 and ten young people with BMI >20, two groups of ten older subjects aged 35–75 with low and high BMI and 20 subjects with diabetes with high BMI were investigated. The general characteristics of the subjects are given in Table 1. No subjects were smokers and all except the subjects with diabetes were not taking cardiovascular medications and were free of cardiovascular and neurological impairments. The subjects with diabetes were free of heart disease and renal disease and were not taking beta or alpha agonists and antagonists. The average HbA1c was 7.9±2.1. The initial study design was to have a group of low BMI people with diabetes, but, we could not find a matched low BMI group to the older and younger low BMI groups. The BMI was not significantly different in the low younger and low older groups and high BMI young and old groups. But the high BMI groups had significantly higher BMI than the low BMI groups (p<0.01). All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Loma Linda University. All participants signed informed consent forms.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the subjects.

| Weight (kg) | Height (cm) | BMI | Age (yrs) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young Low BMI | Mean | 54.0 | 165.8 | 19.6 | 25.0 |

| SD | 8.2 | 7.9 | 1.9 | 3.1 | |

| Young High BMI | Mean | 81.7 | 168.4 | 28.8 | 26.2 |

| SD | 11.5 | 8.4 | 3.3 | 2.7 | |

| Older Low BMI | Mean | 57.7 | 167.9 | 20.2 | 58.6 |

| SD | 10.1 | 9.2 | 1.6 | 13.7 | |

| Older High BMI | Mean | 84.7 | 166.1 | 30.3 | 55.4 |

| SD | 20.3 | 8.8 | 4.4 | 12.2 | |

| Diabetes High BMI | Mean | 91.5 | 172.7 | 30.9 | 64.7 |

| SD | 18.7 | 12.4 | 7.4 | 6.5 | |

Measurement of skin temperature

Skin temperature was measured with a thermistor (SKT RX 202A) manufactured by BioPac systems (BioPac Inc., Goleta, CA). The thermistor output was sensed by an SKT 100 thermistor amplifier (BioPac Inc., Goleta, CA). The output, which was a voltage between 0 and 10 volts, was then sampled with an analog to digital converter at a frequency of a 1,000 samples per second with a resolution of 24 bits with a BioPac MP150 analog to digital converter. The converted data was then stored on a desk top computer using Acknowledge 4.1 software for future analysis. Data analysis was done over a 5 second period for mean temperature. The temperature was calibrated at the beginning of each day by placing the thermistors used in the study in a controlled temperature water bath which will be calibrated against a standard thermometer.

Measurement of skin blood flow

Skin blood flow was measured with a Moor Laser Doppler flow meter (VMS LDF20, Oxford England). The imager uses a red laser beam (632.8 nm) to measure skin blood flow using the Doppler Effect. After warming the laser for 15 to 30 minutes prior to use, the laser was applied to the skin through a fiber optic probe placed above the knee on the quadriceps (Figure 1). The probe was a VP12B. The Moor Laser Doppler flow meter measures blood flow through most of the dermal layer of the skin but does penetrate the entire dermal layer. Blood flow is then calculated in a unit called Flux based on the red cell concentration in red cell velocity with a stated accuracy of ±10%. The tissue thickness sampled is typically 1mm in depth.

Figure 1.

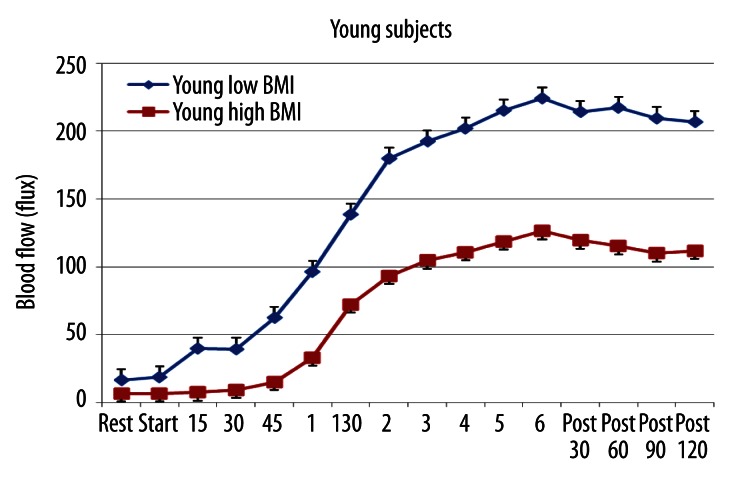

The average blood flow in the skin above the quadriceps muscle in 10 young subjects with low BMI and 10 with high BMI at rest, during 6 minutes of exposure to heat and for 2 minutes after heat exposure. All points are the mean ± the standard deviation.

Control of skin temperature

Skin temperature was controlled by a Moor temperature controller (SH02) with an SHO2-SHP1 skin temperature module which integrated with the blood flow fiber optic probe also shown in Figure 1. This is a closed loop electric warmer (thermode) where temperature is controlled to 0.1°C.

Measurement of the response to heat

The response of the skin to heat was measured by applying the heated probe to the skin for 6 minutes. The thermode was set at a temperature of 44°C. This warmed the skin and blood flow was then recorded.

Procedures

Subjects were interviewed for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Those subjects that were eligible were placed into the study and read and signed a statement of informed consent. Next, subjects rested for 15 minutes while height and weight were taken. Baseline skin blood flow was recorded for 1 minute over the quadriceps. After this period of time, the thermode was applied upon the leg above the belly of the quadriceps muscle to warm the skin to 44°C. The thermode was left on for 6 minutes.

Statistical analysis

Data was summarized as means and standard deviations. For comparison, T test, ANOVA and multiple regression and correlations were calculated. The level of significance was set at p=0.05.

Results

The results for the young subjects with low and high BMI are shown in Figure 1. As shown for the entire young group, blood flow increased slowly at first and then exponentially during the 6 minute heat exposure. However, the blood flow after 1 minute 15 seconds and until the end of the experiment was greater in the low BMI group than the high BMI group (ANOVA p<0.05). From 1 minute 30 seconds to 3 minutes, the slope of the increase in blood flow per minute was the same in both groups of subjects but the magnitude of the increase was less in the low BMI young group (slope difference was p>0.05). As an index of the blood flow increase during heat exposure, the total increase in blood flow above the resting blood flow in the last 5 minutes of heat exposure was calculated in this and all groups of subjects. For the younger group, the correlation between BMI and blood flow during the last 5 minutes of heat exposure was −0.64, a significant correlation (p<0.01) showing that blood flow was reduced as a function of BMI.

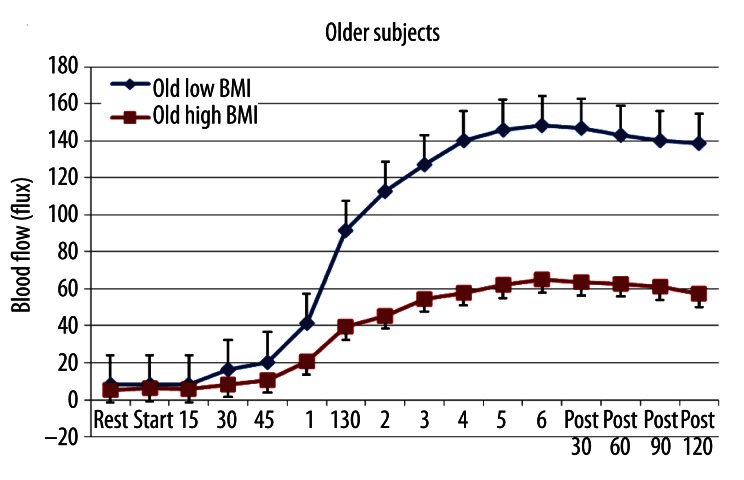

The same was true of the older group (Figure 2). The high BMI older group had a significant impairment in the blood flow response to heat after the first minute that heat was applied. Resting blood flow was not different in the low and high BMI groups (p>0.05). However, after heat was applied, there was a large difference between these groups. As was seen with the younger group, in the older group, there was a significant negative correlation between BMI and blood flow during the last 5 minutes of heat exposure. The correlation here was −0.73, a significant negative correlation (p<0.01).

Figure 2.

The average blood flow in the skin above the quadriceps muscle in 10 older subjects with low BMI and 10 with high BMI at rest, during 6 minutes of exposure to heat and for 2 minutes after heat exposure. All points are the mean ± the standard deviation.

The blood flow during heat exposure was significantly higher in the high BMI younger group than the high BMI older group (p<0.05). Young and old high BMI groups were also significantly different from each other (p<0.05) but the younger group had greater blood flows during heat than that seen in the older group (p<0.05). Thus both ageing and BMI contributed to a lower blood flow response in the last 5 minutes of heat stress.

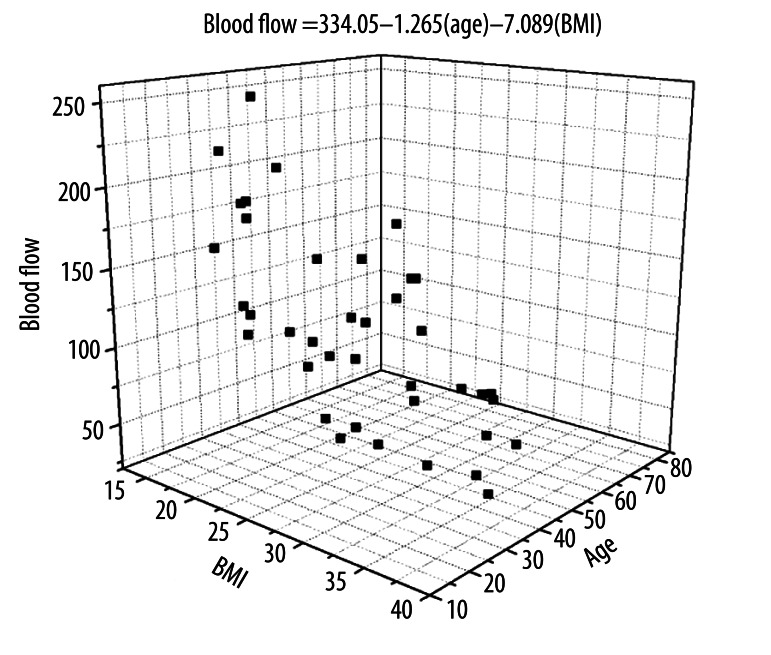

This relationship is shown in the scatter diagram in Figure 3. It is a scatter diagram showing all data on the young and old subjects pooled together. The regression equation in the figure shows that BMI had a more significant effect on reducing the blood flow response to heat than did ageing. The multiple correlation coefficients for age and BMI and blood flow showed the correlation with age was −0.397 and for BMI was −0.70. The R2 therefore showed that about 16% of the loss in circulation was due to age and 49% due to high BMI. These correlations were both significant (p<0.01). Using the regression equation, blood flow in the last 5 minutes of heat exposure was measured in the 10 subjects as an average of 178.4 flux in the young low BMI group as would be predicted by the regression equation in Figure 3 to be 164.1 flux. For the young high BMI group, the actual blood flow measured on the 10 subjects was an average of 94.1 flux and was predicted by the regression equation to be 96.0 flux. For the older low BMI group the actual blood flow measured on the 10 subjects averaged 115.2 flux and was predicted by the regression equation to be 116.1 flux in the last 5 minutes after heat exposure. For the old high BMI group, the actual blood flow for the 10 subjects was an average of was 49.3 flux and was predicted by the regression equation to be 49.2 flux. Thus the regression equation was highly predicative of the results seen in these experiments. For the subjects with diabetes, the blood flows were even lower in response to heat. We could not find low BMI subjects with diabetes and therefore only a high BMI group is shown. As can be seen here, diabetes in itself reduced blood flow even further (Figure 4) for subjects at the same BMI and age as in Figure 2. However, when using the subject’s age and BMI, the equation in Figure 3 predicts the blood flow in the last 5 minutes should be 47.3 flux whereas the actual blood flow in the last 5 minutes averaged, for the 10 subjects in this group, 37.1 flux. The difference is small and supports the idea that only about 20% of the lower blood flow response to heat is due to diabetes itself. The majority of the lower blood flow response to heat is due to high BMI and ageing.

Figure 3.

The average blood flow in the skin above the quadriceps muscle in 20 young subjects with low and high BMI and 20 older subjects with low and high BMI during the last 5 minutes of heat exposure. Data for blood flow is shown compared to age and BMI. The regression equation relates blood flow to age and BMI and is calculated by the method of least squares.

Figure 4.

The average blood flow in the skin above the quadriceps muscle in 10 subjects with diabetes with high BMI. Data is shown at rest, during 6 minutes of exposure to heat and for 2 minutes after heat exposure. All points are the mean ± the standard deviation.

Discussion

Recent studies have shown that a Westernized diet in Asians reduces the skin blood flow in response to heat stress and occlusion due to high concentration of free radicals in blood from the type of fat in the diet [41,44]. Administration of antioxidants reversed this impairment even after high fat meals [44–46]. It is also well established that high concentrations of blood born free radicals are found in people with high BMI’s [36,47,48]. As people age and especially in people with diabetes, BMI is elevated. And yet, no study has examined the interrelationship between BMI and blood flow in response to stressors such as heat. Since free radicals are high in older people and people who have diabetes, it might be anticipated that diabetes and ageing would have some impact through these free radicals in the blood thereby reducing endothelial function [25,26,42]. Thus the purpose of the present research study was to examine how much reduction in endothelial function was there in people with diabetes: 1) that was due to ageing and, 2) how much was due to BMI and, 3) how much is due to diabetes itself.

The results presented here would appear to confirm this hypothesis. Even young subjects had a reduced blood flow response to heat stress if they had a high BMI. In subjects who had diabetes, we were not able to find a low BMI group. However, for this group of subjects, the differential effects of age and diabetes could be deduced by examining the age matched controls. When the contributions of age and BMI are eliminated from the blood flow response to heat stress, BMI, and diabetes are not equal contributors to impaired endothelial function. By and large, BMI appears to be the major contributor to endothelial dysfunction, ageing contributes a small amount, and the remainder appears to be due to diabetes and poor glycemic control.

Suggested ways to reduce this endothelial damage is a lifestyle change with an increase in exercise and a reduction of body weight [49]. Exercise has been shown to increase free radicals during the actual exercise but, with training, appears to optimize the immune response, thereby, producing an overall reduction in body inflammation [49]. Another approach would be to increase the intake of antioxidants. This has been shown to increase blood flow to tissue in even a young population [46,50,51]. However, this is especially true and significant with high fat diets in populations such as Asians who have a poor tolerance for high fat foods and thus produce free radicals after even a single high fat meal [40,46,51]. When Asians took antioxidants there was an increase in their blood flow in response to heat stress and occlusion in spite of the high fat meal [44]. Also, even a simple change in diet, for example, drinking green tea or taking green tea extract has been shown to reduce cellular inflammation by blocking the activation of NFKb, the nuclear sub transmitter that activates inflammation in cells[52,53]. In addition, there are also many other sources of free radical scavengers in the diet.

However, it should be stated that free radicals are also used for cellular communication, including in muscle during exercise [54]. Red blood cells release nitric oxide (a fee radical) to increase the diameter of arteries if they encounter high shear stresses [55]. Endothelial cells release nitric oxide in response to heat and other stressors to increase circulation [50]. The mitochondria in muscle release nitric oxide to increase energy delivery to the cell through increased blood flow if the mitochondria are active [48,49]. Thus, free radicals are critical for cell function. Therefore, an overdose of anti-oxidants such as vitamins A, C and E can impair exercise performance [56]. Thus the dosage of antioxidants must be given in response to the excess free radicals found in the body. For even young people with a high BMI, one dose is needed in the diet or with supplements of antioxidants while for people with diabetes and those who have high BMI and who are older, a much greater dosage should be considered for every day. This would explain various studies showing no effect of antioxidants in younger people who are thin but increased endothelial function in younger people with a high BMI. Endothelial function in older people also seems to improve with antioxidant dosage, again supporting this hypothesis that it is free radicals that reduce endothelial function [57]. Further research needs to be conducted on the dosage vs. diabetes and age of various antioxidants including vitamin D, an emerging modulator of the immune mechanisms [58]. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with endothelial dysfunction [58]. Current government recommended dosages of vitamins do not take into consideration age, race, or diabetes. Race also contributes to increased free radicals. Due to thrifty genes, Asians produce abnormally high free radicals in their blood in response to high fat foods [44]. But the effect of ageing and diabetes in Asians has not been examined. It would appear that with a Westernized diet, this group would need even higher antioxidants in their diets. Therefore, further research is needed to enhance these significant preliminary findings and elaborate on the issues of accurate and appropriate anti-oxidant supplementation for different races, age categories and even chronic disease states (diabetes, CVD) so appropriate lifestyle adjustments can be recommended.

Conclusions

Ageing and diabetes are associated with impairment in vascular endothelial function.

Thus the blood flow response to stressors such as heat or occlusion is reduced with ageing and diabetes as well as blood flow to other organs.

The present investigation shows that the majority of this impairment is due to body fat and not ageing and diabetes itself.

The damage we associate with ageing is probably largely due to high concentrations of free radicals damaging the endothelial cells due to obesity.

Thus even young people with a high BMI show significant damage to vascular endothelial function.

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.van Tubergen A, van der Linden S. A brief history of spa therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(3):273–75. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.3.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKemy DD, Neuhausser WM, Julius D. Identification of a cold receptor reveals a general role for TRP channels in thermosensation. Nature. 2002;416(6876):52–58. doi: 10.1038/nature719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peier AM, et al. A TRP channel that senses cold stimuli and menthol. Cell. 2002;108(5):705–15. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00652-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reid G. ThermoTRP channels and cold sensing: what are they really up to? Pflugers Arch. 2005;451(1):250–63. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1437-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voets T, et al. Sensing with TRP channels. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1(2):85–92. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0705-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mergler S, et al. Thermosensitive transient receptor potential channels (thermo-TRPs) in human corneal epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol. :2010. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owsianik G, et al. Permeation and selectivity of TRP channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:685–717. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040204.101406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedersen SF, Owsianik G, Nilius B. TRP channels: an overview. Cell Calcium. 2005;38(3–4):233–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramsey IS, Delling M, Clapham DE. An introduction to TRP channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:619–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040204.100431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nilius B, et al. Transient receptor potential cation channels in disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(1):165–217. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venkatachalam K, Montell C. TRP channels. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:387–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benham CD, Davis JB, Randall AD. Vanilloid and TRP channels: a family of lipid-gated cation channels. Neuropharmacology. 2002;42(7):873–88. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nilius B, et al. TRPV4 calcium entry channel: a paradigm for gating diversity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286(2):C195–205. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00365.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nilius B, Watanabe H, Vriens J. The TRPV4 channel: structure-function relationship and promiscuous gating behaviour. Pflugers Arch. 2003;446(3):298–303. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Everaerts W, Nilius B, Owsianik G. The vanilloid transient receptor potential channel TRPV4: from structure to disease. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2010;103(1):2–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caterina MJ, et al. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389(6653):816–24. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caterina MJ, Julius D. The vanilloid receptor: a molecular gateway to the pain pathway. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:487–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tominaga M. The Role of TRP Channels in Thermosensation. 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tominaga M, et al. The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain-producing stimuli. Neuron. 1998;21(3):531–43. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cesare P, et al. Specific involvement of PKC-epsilon in sensitization of the neuronal response to painful heat. Neuron. 1999;23(3):617–24. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80813-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liedtke W, et al. Vanilloid receptor-related osmotically activated channel (VR-OAC), a candidate vertebrate osmoreceptor. Cell. 2000;103(3):525–35. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00143-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strotmann R, et al. OTRPC4, a nonselective cation channel that confers sensitivity to extracellular osmolarity. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(10):695–702. doi: 10.1038/35036318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wissenbach U, et al. Trp12, a novel Trp related protein from kidney. FEBS Lett. 2000;485(2–3):127–34. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kellogg DL, Jr, et al. Role of nitric oxide in the vascular effects of local warming of the skin in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86(4):1185–90. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.4.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minson CT, Berry LT, Joyner MJ. Nitric oxide and neurally mediated regulation of skin blood flow during local heating. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91(4):1619–26. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.4.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minson CT, et al. Decreased nitric oxide- and axon reflex-mediated cutaneous vasodilation with age during local heating. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93(5):1644–49. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00229.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Namer B, et al. Chemically and electrically induced sweating and flare reaction. Auton Neurosci. 2004;114(1-2):72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petrofsky JS, Al-Malty AM, Prowse M. Relationship between multiple stimuli and skin blood flow. Med Sci Monit. 2008;14(8):CR399–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sauerstein K, et al. Electrically evoked neuropeptide release and neurogenic inflammation differ between rat and human skin. J Physiol. 2000;529:803–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Almalty AM, et al. An effective method for skin blood flow measurement using local heat combined with electrical stimulation. J Med Eng Technol. 2009;33(8):663–69. doi: 10.3109/03091900903271646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rowell LB. Human cardiovascular adjustments to exercise and thermal stress. Physiol Rev. 1974;54(1):75–159. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1974.54.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rowell LB. Reflex control of the cutaneous vasculature. J Invest Dermatol. 1977;69(1):154–66. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12497938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petrofsky J, et al. The interrealtionship between locally applied heat, ageing and skin blood flow on heat transfer into and from the skin. J Med Eng Technol. 2011;35(5):262–74. doi: 10.3109/03091902.2011.580039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petrofsky J, et al. The ability of different areas of the skin to absorb heat from a locally applied heat source: the impact of diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13(3):365–72. doi: 10.1089/dia.2010.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petrofsky J, et al. The ability of the skin to absorb heat; the effect of repeated exposure and age. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17(1):CR1–8. doi: 10.12659/MSM.881315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vecchini A, et al. Dietary alpha-linolenic acid reduces COX-2 expression and induces apoptosis of hepatoma cells. J Lipid Res. 2004;45(2):308–16. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300396-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong BJ, Fieger SM. Transient receptor potential vanilloid type-1 (TRPV-1) channels contribute to cutaneous thermal hyperaemia in humans. J Physiol. 2010;588(Pt 21):4317–26. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.195511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petrofsky J, et al. Dry heat, moist heat and body fat: are heating modalities really effective in people who are overweight? J Med Eng Technol. 2009;33(5):361–69. doi: 10.1080/03091900802355508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farage M, Miller K, Maibach H, editors. Influence of Race, Gender, Age and Diabetes on the Skin Circluation Text Book of Ageing Skin. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bui C, et al. Acute effect of a single high-fat meal on forearm blood flow, blood pressure and heart rate in healthy male Asians and Caucasians: a pilot study. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2010;41(2):490–500. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yim J, et al. Differences in endothelial function between Korean-Asians and Caucasians. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18(6):CR337–43. doi: 10.12659/MSM.882902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Calder PC, et al. Dietary factors and low-grade inflammation in relation to overweight and obesity. Br J Nutr. 2011;106(Suppl 3):S5–78. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511005460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Heredia FP, Gomez-Martinez S, Marcos A. Obesity, inflammation and the immune system. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012;71(2):332–38. doi: 10.1017/S0029665112000092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yim J, et al. Protective effect of anti-oxidants on endothelial function in young Korean-Asians compared to Caucasians. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18(8):CR467–79. doi: 10.12659/MSM.883266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. [Practical study of the establishment of menus in general hospital, with a view to a diet balanced and adapted to different categories of hospitalized patients]. Terramycine Informations. 1960;16:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petrofsky JS, Laymon M, Lee H, et al. The Effect of Coenzyme Q-10 on Endothelial Function in a Young Population. Physical Therapy Rehabilitation Science. 2012;1:6–12. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Higdon JV, Frei B. Obesity and oxidative stress: a direct link to CVD? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(3):365–67. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000063608.43095.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Middleton E, Jr, Kandaswami C, Theoharides TC. The effects of plant flavonoids on mammalian cells: implications for inflammation, heart disease, and cancer. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52(4):673–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Powers SK, Jackson MJ. Exercise-induced oxidative stress: cellular mechanisms and impact on muscle force production. Physiol Rev. 2008;88(4):1243–76. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petrofsky JS. Resting blood flow in the skin: does it exist, and what is the influence of temperature, aging, and diabetes? J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6(3):674–85. doi: 10.1177/193229681200600324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petrofsky JS, et al. Reduced endothelial function in the skin in Southeast Asians compared to Caucasians. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18(1):CR1–8. doi: 10.12659/MSM.882185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Babu PV, Liu D. Green tea catechins and cardiovascular health: an update. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15(18):1840–50. doi: 10.2174/092986708785132979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Babu PV, Sabitha KE, Shyamaladevi CS. Effect of green tea extract on advanced glycation and cross-linking of tail tendon collagen in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46(1):280–85. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Powers SK, Talbert EE, Adhihetty PJ. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species as intracellular signals in skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2011;589(Pt 9):2129–38. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.201327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baskurt OK, Ulker P, Meiselman HJ. Nitric oxide, erythrocytes and exercise. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2011;49(1–4):175–81. doi: 10.3233/CH-2011-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peternelj TT, Coombes JS. Antioxidant Supplementation during Exercise Training: Beneficial or Detrimental? Sports Med. 2011;41(12):1043–69. doi: 10.2165/11594400-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wray DW, et al. Acute reversal of endothelial dysfunction in the elderly after antioxidant consumption. Hypertension. 2012;59(4):818–24. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.189456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tare M, et al. Vitamin D insufficiency is associated with impaired vascular endothelial and smooth muscle function and hypertension in young rats. J Physiol. 2011;589(Pt 19):4777–86. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.214726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]