Abstract

Background

It is not known whether geographic differences in the prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) exist and are associated with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) incidence rates across the US.

Study Design

Cross-sectional and ecologic.

Setting & Participants

White (n=16,410) and black (n=11,109) participants from across the continental US in the population-based Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study.

Predictor

Geographic region, defined by the 18 Networks of the US ESRD Network Program.

Outcomes & Measurements

Albuminuria, defined as an albumin-creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g and reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), defined as levels <60 ml/min/1.73m2, were measured in the REGARDS study. ESRD incidence rates were obtained from the US Renal Data System.

Results

For whites, the Network-specific prevalence of albuminuria ranged from 8.4% (95% CI, 3.3%–13.5%) in Network 15 to 14.8% (95% CI, 8.0%–21.6%) in Network 3, and reduced eGFR ranged from 4.3% (95% CI, 2.0%–6.6%) in Network 4 to 16.7% (95% CI, 12.7%–20.7%) in Network 7. For blacks, the prevalence of albuminuria ranged from 12.1% (95% CI, 8.7%–15.5%) in Network 5 to 26.5% (95% CI, 16.7%–36.3%) in Network 4, and reduced eGFR ranged from 6.7% (95% CI, 5.0%–8.4%) in Network 17/18 to 13.4% (95% CI, 7.8%–19.1%) in Network 12. The Spearman correlation coefficients for the prevalence of albuminuria and reduced eGFR with Network-specific ESRD incidence rates were 0.49 and 0.24, respectively, for whites and 0.29 and 0.25, respectively, for blacks.

Limitations

There were few cases of albuminuria and reduced eGFR in some geographic regions.

Conclusions

In the US, substantial geographic variations in the prevalence of albuminuria and reduced eGFR exist but were only modestly correlated with ESRD incidence, suggesting the CKD burden may not explain the geographic variation in ESRD incidence.

Over 20 million US adults have chronic kidney disease (CKD).1 CKD poses a significant public health challenge, given its high prevalence and strong association with cardiovascular disease (CVD), end-stage renal disease (ESRD), and mortality.2–4

ESRD incidence varies substantially across regions of the United States.5 It has been hypothesized that geographic variation in ESRD incidence may reflect regional differences in CKD prevalence.6 However, few data on geographic variation in CKD prevalence among US adults are available.

The goal of the current analysis was to evaluate whether geographic variation in the prevalence of albuminuria or reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) exists in the United States. We hypothesized that there would be substantial differences in the prevalence of albuminuria and reduced eGFR across geographic areas and that the prevalence of albuminuria and reduced eGFR would be correlated with region-specific ESRD incidence rates. To test these hypotheses we analyzed data from a cohort of adults participating in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study.

METHODS

Study Participants

The REGARDS study is a population-based cohort study of black and white US adults ≥45 years of age.7 Participants were recruited from the 48 contiguous US states and the District of Columbia. The study was designed to oversample blacks and residents of the geographic regions referred to as the “Stroke Buckle” (coastal North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia) and “Stroke Belt” (remainder of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia; Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana). Over half (56%) of REGARDS participants were recruited from these 2 geographic regions, with the remaining 44% of the sample recruited from the rest of the continental US.

The REGARDS study enrolled 30,239 participants between June 2003 and October 2007. Individuals missing serum creatinine or missing urine albumin or creatinine data (n=2,417) were excluded from this analysis. Additionally, participants reporting being on dialysis at baseline (n=116) or who did not answer the question “Are you on dialysis?” at baseline (n=187) were excluded. After these exclusion criteria were applied, data from 27,519 participants were analyzed (n=16,410 whites and n=11,109 blacks). The REGARDS study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards governing research in human subjects at the participating centers and all participants provided written consent.

Data Collection

Baseline REGARDS study data were collected through a computer-assisted telephone interview followed by an in-home examination, conducted in the morning. Of relevance to the current analysis, the following demographic and behavioral characteristics were collected during the interview: age, sex, race, education, annual household income, smoking status, health insurance status, and self-report of co-morbidities (i.e., hypertension; diabetes; dyslipidemia; and stroke, myocardial infarction, and history of revascularization procedures). Race and ethnicity were self-reported using the questions “Are you Hispanic or latino?” and “What is your race? Would you say white, black or African American, Asian, native Hawaiian or other Pacific islander, Alaska native, or some other race?” Due to the goals of the parent REGARDS study, only white or black individuals who were not Hispanic were eligible for enrollment. During the in-home examination, standardized protocols were followed to obtain two blood pressure measurements which were averaged for analysis, an electrocardiogram, height and weight, and blood and urine samples. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg and/or use of antihypertensive medication. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Obesity was defined as a BMI ≥30 kg/m2. Diabetes was defined as a fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL, non-fasting glucose ≥200 mg/dL, or use of anti-diabetes medication. CVD was defined as a history of stroke, myocardial infarction (self-reported or on the study electrocardiogram), or revascularization procedure.

Definition of Albuminuria and Reduced eGFR

Using spot samples collected during the in-home examination, urinary albumin was measured with the BN ProSpec nephelometer (Dade Behring). Urinary creatinine was measured with a rate-blanked Jaffé procedure, using the Modular-P analyzer (Roche/Hitachi). Albuminuria was defined as a urinary albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR) ≥30 mg/g. Using the blood sample collected during the in-home examination, serum creatinine was measured using an isotope-dilution mass spectrometry (IDMS) traceable method. eGFR was calculated via the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) creatinine equation.8 Reduced eGFR was defined as levels <60 ml/min/1.73m2. We also evaluated having both albuminuria and reduced eGFR jointly (i.e., ACR ≥30 mg/g and eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2) as an outcome.

ESRD Incidence Rates by ESRD Network

Eighteen Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)-sponsored ESRD networks serve as liaisons between the federal government and providers of ESRD services.9 These Networks are defined geographically with consideration given to the number and concentration of ESRD beneficiaries in each area.9,10 Networks 9 and 10 are administratively pooled by CMS. Networks 17 and 18 both comprise parts of California, so we pooled them for our analyses. After pooling, 16 Networks were considered in the current analysis (as shown in the table component of Fig 1).

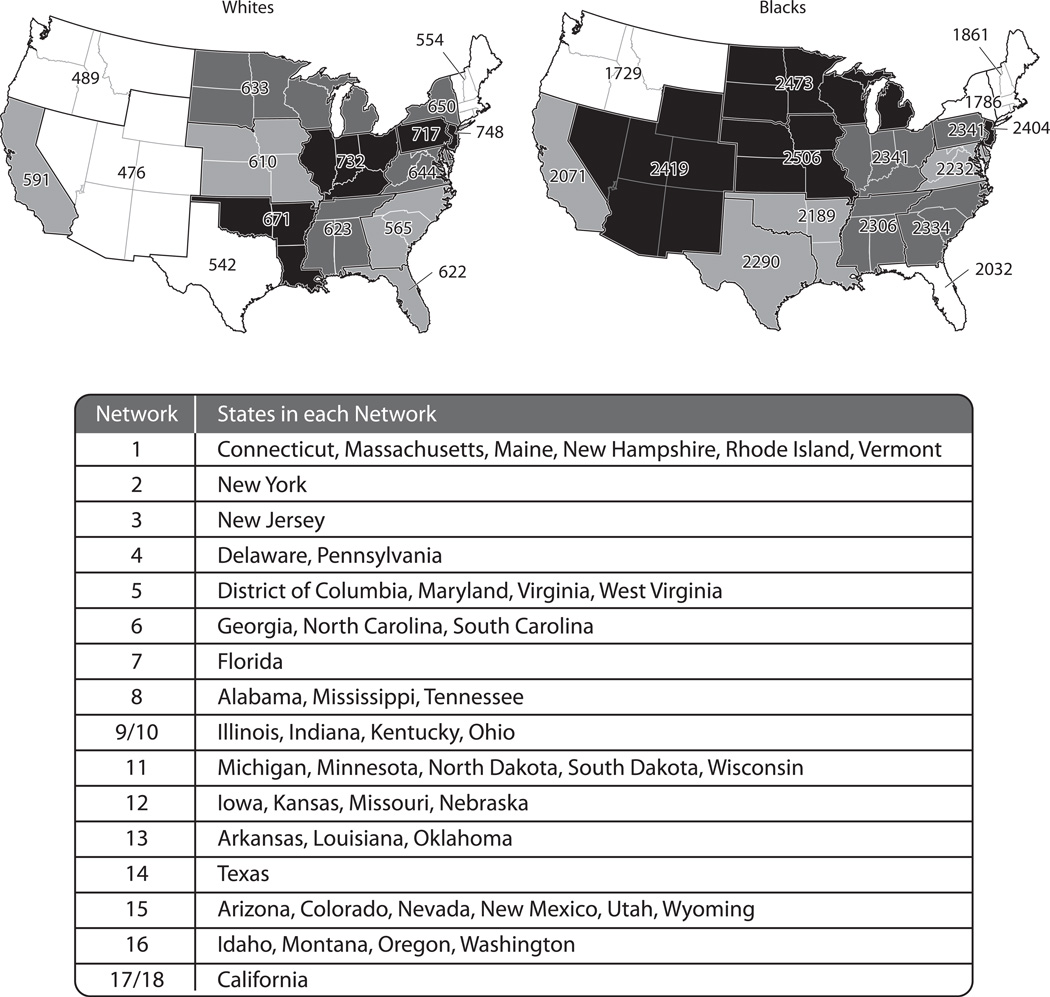

Figure 1.

End-stage renal disease incidence rates per million population in 2005 by end-stage renal disease network among whites (left) and blacks (right) ≥45 years.

The table is limited to the continental US as the REGARDS study did not recruit participants from Alaska, Hawaii, or US protectorates.

Race-specific ESRD incidence rates were calculated for each ESRD Network separately for blacks and whites ≥45 years of age. Counts of incident ESRD cases among individuals ≥45 years of age were abstracted for each state for 2005 from the US Renal Data System (USRDS) Renal Data Extraction and Referencing (RenDER) System.5 The USRDS records demographic and clinical information on all patients with ESRD who initiate renal replacement therapy and survive greater than 90 days from the initiation of therapy. The total number of black and white adults ≥45 years of age living in each state in July 2005 was determined from US census data11 and summed across the states in each ESRD Network. ESRD incidence rates were calculated as the number of incident ESRD cases divided by the total number of adults in each Network. The year 2005 was chosen for this calculation as it represents the approximate mid-point of enrollment of REGARDS participants.

Statistical Analysis

Due to marked differences in ESRD incidence rates between blacks and whites12, all analyses were stratified by race. Two Networks (15 and 16) were not analyzed for blacks due to the small sample size (n<50) of black REGARDS participants in these regions, leaving 16 Networks for the analysis of whites and 14 Networks for the analysis of blacks. In a sensitivity analysis, we excluded Networks 15 and 16 for both whites and blacks. Characteristics of REGARDS participants and the prevalence of albuminuria, reduced eGFR, and both albuminuria/reduced eGFR were calculated by ESRD Network. In a secondary analysis, we calculated the prevalence of albuminuria and reduced eGFR by ESRD Network for whites and blacks 45 to 64 years of age and ≥65 years of age, separately. The statistical significance of differences in the prevalence of albuminuria, reduced eGFR, and both albuminuria/reduced eGFR across ESRD Network (p-value for homogeneity) was determined using logistic regression. In a secondary analysis, the prevalence of albuminuria, reduced eGFR, and both albuminuria/reduced eGFR were calculated by stroke region of residence (non-stroke belt, stroke belt, or stroke buckle). Next, the prevalence of albuminuria, reduced eGFR, and both albuminuria/reduced eGFR among REGARDS participants residing in each Network was plotted against ESRD incidence rates from USRDS RenDER data, and Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated. In a sensitivity analysis, we calculated the prevalence of ACR ≥300 mg/g and eGFR <45 ml/min/1.73 m2 and the correlation with these factors with Network specific ESRD incidence rates. Also, Spearman correlation coefficients between characteristics of people residing in each ESRD Network and Network-specific ESRD incidence rates were calculated. Characteristics evaluated include mean age of the population, percentage that were women, and the prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and CVD. Finally, we calculated the age-sex adjusted prevalence of albuminuria, reduced eGFR, and both albuminuria/reduced eGFR across ESRD Network. All analyses were weighted to provide US population estimates for blacks and whites ≥45 years of age. Weighting took into account the sampling of individuals for enrollment into REGARDS and US census estimates for 120 REGARDS sampling units defined by age, race, sex, and region of residence. Each participant’s weight is equal to the inverse probability of their being selected for inclusion into the REGARDS study. Analyses were conducted using SUDAAN version 10 (RTI International) accounting for the stratified sampling approach employed in the REGARDS study.

RESULTS

Findings by ESRD Network

Incidence of ESRD

Among whites ≥45 years of age, ESRD incidence rates ranged from 476 per million adults in Network 15 to 748 per million adults in Network 3 (Figure 1). For blacks ≥45 years of age, ESRD incidence rates were higher and ranged from 1,729 per million adults in Network 16 to 2,506 per million adults in Network 12.

Prevalence of Albuminuria and Reduced eGFR

There were significant differences for whites in the mean age and proportion with a household income <$20,000, diabetes, hypertension and a history of CVD across ESRD Networks (Table 1). For black REGARDS participants, there were significant differences in the mean age and proportion with a household income <$20,000 and diabetes across ESRD Networks. There were also differences across race within ESRD Network. For example, blacks had a higher prevalence of diabetes, hypertension and obesity than whites within each Network.

Table 1.

Characteristics of REGARDS study participants by ESRD network of residence

| ESRD Network | Whites | Blacks | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size |

Age (y) | Male Sex |

Income <$20,000 |

DM | HTN | Obese | History of CVD |

Sample Size |

Age (y) | Male | Income <$20,000 |

DM | HTN | Obese | History of CVD |

|

| Overall | 16,410 | 61.4 (0.02) | 47.7 | 11.2 | 11.8 | 41.4 | 31.2 | 17.0 | 11,109 | 59.0 (0.02) | 44.4 | 25.8 | 24.3 | 64.2 | 47.4 | 17.2 |

| 1 | 295 | 61.4 (1.1) | 47.0 | 6.0 | 6.9 | 36.3 | 20.5 | 14.0 | 61 | 61.4 (2.0) | 33.9 | 31.8 | 28.2 | 57.3 | 47.1 | 8.7 |

| 2 | 357 | 61.1 (0.9) | 47.4 | 8.7 | 14.5 | 43.4 | 31.3 | 13.4 | 447 | 59.3 (0.9) | 41.9 | 29.0 | 22.2 | 64.2 | 35.0 | 16.3 |

| 3 | 106 | 63.5 (2.0) | 46.4 | 6.9 | 10.0 | 45.6 | 28.0 | 22.4 | 100 | 61.5 (1.9) | 36.0 | 10.8 | 25.3 | 60.4 | 50.9 | 14.5 |

| 4 | 349 | 59.6 (0.9) | 51.1 | 14.1 | 9.7 | 39.7 | 33.5 | 16.7 | 262 | 61.4 (1.3) | 39.2 | 34.4 | 31.1 | 71.4 | 45.9 | 24.5 |

| 5 | 555 | 61.7 (0.8) | 55.5 | 9.3 | 11.0 | 40.7 | 29.3 | 18.4 | 603 | 58.6 (0.7) | 49.5 | 11.5 | 22.6 | 63.6 | 49.2 | 15.9 |

| 6 | 5,772 | 60.9 (0.2) | 48.4 | 12.8 | 14.8 | 45.0 | 32.3 | 17.6 | 3,033 | 59.2 (0.2) | 43.8 | 24.7 | 27.1 | 64.9 | 48.3 | 16.5 |

| 7 | 605 | 65.9 (0.8) | 41.9 | 18.9 | 12.5 | 48.5 | 30.9 | 22.5 | 361 | 59.9 (0.9) | 46.7 | 27.3 | 32.8 | 66.8 | 49.7 | 15.6 |

| 8 | 2,261 | 61.7 (0.3) | 44.7 | 14.8 | 15.1 | 47.4 | 30.4 | 20.2 | 1,542 | 58.9 (0.3) | 43.3 | 31.6 | 26.1 | 67.3 | 48.2 | 15.9 |

| 9/10 | 1,075 | 60.5 (0.5) | 48.0 | 12.6 | 13.1 | 43.3 | 32.8 | 18.7 | 1,227 | 59.7 (0.4) | 45.1 | 24.3 | 21.2 | 61.4 | 45.2 | 17.9 |

| 11 | 827 | 59.8 (0.6) | 47.6 | 10.8 | 8.6 | 37.4 | 33.3 | 15.2 | 703 | 58.0 (0.6) | 44.5 | 31.7 | 19.3 | 66.7 | 46.9 | 20.4 |

| 12 | 457 | 61.0 (0.8) | 48.4 | 12.5 | 12.4 | 40.2 | 37.3 | 16.5 | 240 | 59.8 (1.2) | 45.0 | 20.6 | 25.6 | 64.5 | 50.9 | 15.8 |

| 13 | 1,690 | 60.7 (0.5) | 51.7 | 15.0 | 15.4 | 46.9 | 32.9 | 17.9 | 1,142 | 58.4 (0.4) | 44.1 | 39.4 | 25.8 | 67.8 | 52.2 | 20.0 |

| 14 | 382 | 62.6 (0.9) | 49.7 | 9.5 | 12.7 | 43.7 | 35.5 | 20.2 | 393 | 61.5 (1.0) | 47.4 | 30.6 | 29.7 | 63.4 | 46.5 | 22.4 |

| 15 | 288 | 63.4 (0.9) | 47.1 | 9.3 | 8.1 | 41.9 | 31.9 | 14.4 | 24 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 16 | 265 | 63.2 (1.2) | 48.2 | 10.0 | 10.4 | 39.0 | 26.5 | 18.3 | 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 17/18 | 1,126 | 61.0 (0.5) | 44.8 | 7.0 | 11.3 | 35.9 | 28.1 | 13.5 | 970 | 57.2 (0.4) | 44.5 | 16.8 | 21.1 | 58.6 | 48.2 | 13.9 |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.06 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.1 | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | ||

Note: Except for sample size, values are presented as mean ( standard error) or percentage and are weighted to the US population.

Abbreviations and definitions: NA: not applicable ( not reported due to small number ( n<50) of blacks in these Networks); ESRD: end-stage renal disease; DM: diabetes mellitus, defined as fasting serum glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL, non-fasting serum glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL, or use of anti-diabetes medication; HTN: hypertension, defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, and/or use of antihypertensive medication; obesity defined as body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2; CVD: cardiovascular disease, defined as a self-reported history of coronary artery disease and/or stroke; REGARDS, Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke study

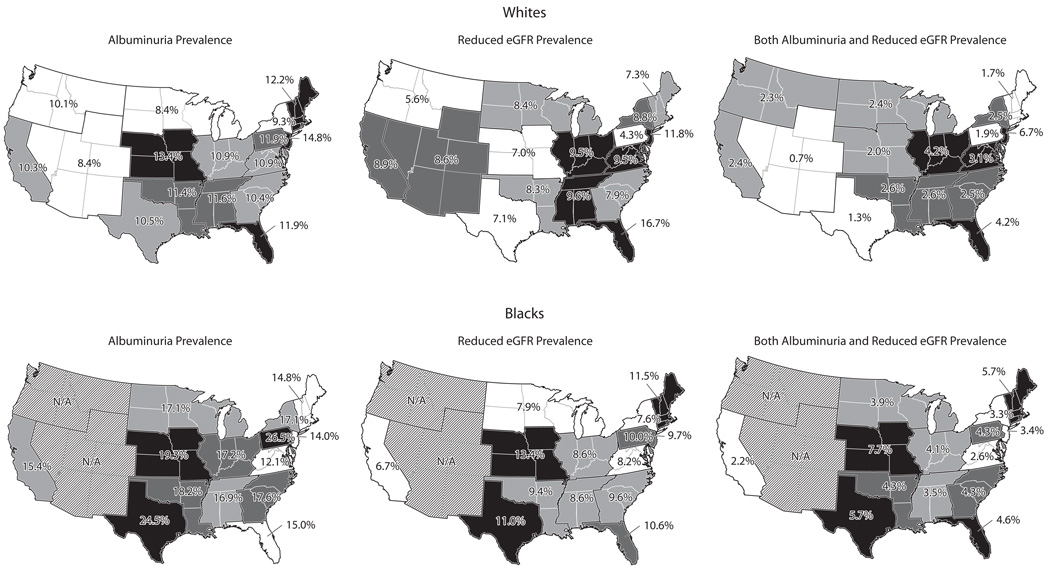

Figure 2 and Table S1 (provided as online supplementary material) show the prevalence of albuminuria, reduced eGFR, and both albuminuria/reduced eGFR by ESRD Network. For whites, the prevalence of albuminuria ranged from 8.4% (95% CIs, 6.2%–10.6% and 3.3%–13.5%, respectively) in Networks 11 and 15 to 14.8% (95% CI, 8.0%–21.6%) in Network 3 (p-value for homogeneity=0.7). The prevalence of reduced eGFR ranged from 4.3% (95% CI, 2.0%–6.6%) in Network 4 to 16.7% (95% CI, 12.7%–20.7%) in Network 7 (p-value for homogeneity <0.001), and the prevalence of both albuminuria/reduced eGFR among whites ranged from 0.7% (95% CI, 0.0%–1.5%) in Network 15 to 6.7% (95% CI, 1.9%–11.5%) in Network 3 (p-value for homogeneity=0.03). For blacks, the prevalence of albuminuria ranged from 12.1% (95% CI, 8.7%–15.5%) in Network 5 to 26.5% (95% CI, 16.7%–36.3%) in Network 4 (p-value for homogeneity=0.1). The prevalence of reduced eGFR in blacks ranged from 6.7% (95% CI, 5.0%–8.4%) in Network 17/18 to 13.4% (95% CI, 7.8%–19.1%) in Network 12 (p-value for homogeneity=0.4) The prevalence of both albuminuria/reduced eGFR among blacks ranged from 2.2% (95% CI, 1.4%–3.0%) in Network 17/18 to 7.7 (95% CI, 2.9%–12.5%) in Network 12 (p-value for homogeneity=0.1). Table S2 shows the prevalence of albuminuria and reduced eGFR by ESRD Network for whites and blacks 45 to 64 years of age and ≥65 years of age, separately. Table S3 shows the prevalence of ACR ≥300 mg/g and eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73m2 by ESRD Network.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of albuminuria† (left), reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR; center)‡, and both albuminuria/reduced eGFR (right) by end-stage renal disease network of residence among white (top panel) and blacks (bottom panel) REGARDS participants.

N/A: Estimates not shown due to insufficient sample size (n<50) for blacks in these regions.

Prevalence is weighted to represent the US population.

† Albuminuria defined as albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) ≥30 mg/g

‡ Reduced eGFR defined as levels <60 mL/min/1.73m2

Correlation of Prevalence of Albuminuria, Reduced eGFR With ESRD Incidence

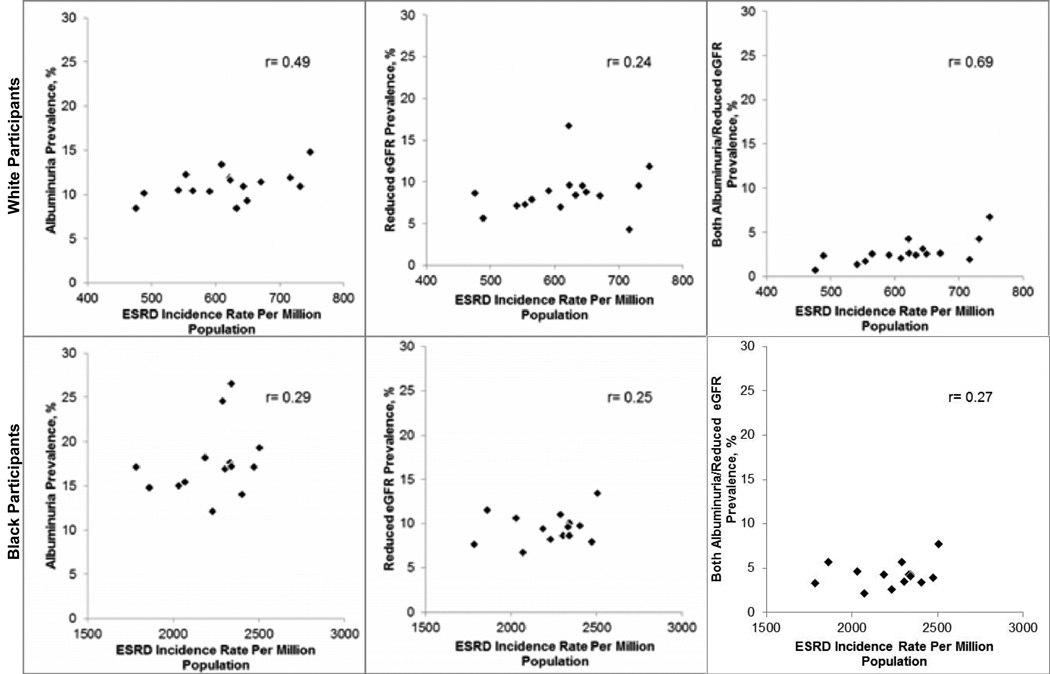

Among whites, the Spearman correlation coefficient of Network-specific prevalence of albuminuria, reduced eGFR, and both albuminuria/reduced eGFR with Network-specific ESRD incidence rates was 0.49, 0.24, and 0.69, respectively (Figure 3, top panel). After excluding Networks 15 and 16 for whites as we did for blacks, the Spearman correlation coefficients were 0.32 for albuminuria, 0.13 for reduced eGFR, and 0.67 for both albuminuria/reduced eGFR. For blacks, the Spearman correlation coefficients of Network-specific prevalence of albuminuria, reduced eGFR, and both albuminuria/reduced eGFR with Network-specific ESRD incidence rates were 0.29, 0.25, and 0.27, respectively. Among whites, the Spearman correlation coefficients for Network-specific ESRD incidence rates versus a prevalence of ACR ≥300 mg/g and eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73m2 were 0.35 and 0.41, respectively (Figure S1, top panel). For blacks, the analogous Spearman correlation coefficients were 0.24 and 0.30, respectively (Figure S1, bottom panel).

Figure 3.

Correlation of end-stage renal disease network-specific prevalence of albuminuria† (left), reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate‡ (center), and both albuminuria/reduced eGFR (right) among REGARDS participants with USRDS-derived end-stage renal disease incidence rates for whites (top panel) and blacks (bottom panel).

r= Spearman correlation coefficient

†Albuminuria defined as an albumin to creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g

‡Reduced eGFR defined as levels <60 ml/min/1.73m2

Networks 15 and 16 excluded for blacks due to small sample size (n<50) for blacks in these regions

Table 2 shows the Spearman correlation coefficients of mean age, gender and the prevalence of income <$20,000, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and history of CVD with Network-specific ESRD incidence rate for whites and blacks, separately. For whites, the highest correlation was between income <$20,000 (r=0.57) with Network-specific ESRD incidence rates. For blacks, obesity and history of CVD had the highest Spearman correlation coefficient with Network-specific ESRD incidence rates (each r=0.49).

Table 2.

Spearman correlation coefficient between ESRD Network-specific mean covariatesand Network-specific ESRD incidence rates

| Whites | Blacks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate* | r (95%CI) | p-value | r (95%CI) | p-value |

| Age | −0.32 (−0.70 to 0.22) | 0.2 | 0.07 (−0.48, 0.57) | 0.8 |

| Gender | 0.14 (−0.39, 0.59) | 0.6 | 0.22 (−0.36, 0.67) | 0.4 |

| Income <$20,000 | 0.57 (−0.08, 0.82) | 0.02 | −0.24 (−0.68, 0.34) | 0.4 |

| Diabetes | 0.24 (−0.30, 0.65) | 0.4 | −0.12 (−0.61, 0.45) | 0.7 |

| Hypertension | 0.28 (−0.26, 0.67) | 0.3 | 0.25 (−0.34. 0.68) | 0.4 |

| Obesity | 0.19 (−0.34, 0.62) | 0.5 | 0.49 (−0.07, 0.80) | 0.1 |

| History of CVD | 0.31 (−0.23, 0.69) | 0.2 | 0.49 (−0.07, 0.80) | 0.1 |

Note: r= Spearman correlation coefficient. Networks 15 and 16 were excluded for blacks because of small (n<50) number of blacks in these Networks. See Table 1 for mean age and prevalence of characteristics by ESRD Network and Figure 1 for Network-specific ESRD incidence rates.

ESRD, end-stage renal disease; CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease

Age/Sex-Adjusted Prevalence of Albuminuria and Reduced eGFR

Table S4 shows the age-sex adjusted prevalence of albuminuria, reduced eGFR, and both albuminuria/reduced eGFR by ESRD Network. After age-sex adjustment, the prevalence of albuminuria ranged from 8.0% (95% CI 3.1%–12.9%) to 13.8% (95% CI, 7.9%–19.7%), the prevalence of reduced eGFR ranged from 4.8% (95% CI, 2.4%–7.2%) to 11.8% (95% CI, 9.1%–14.5%), and the prevalence of both albuminuria/reduced eGFR ranged from 0.7% (95% CI, 0.0%–1.5%) to 5.7% (95% CI, 1.8%–9.6%) across ESRD networks among whites. For blacks, the prevalence of albuminuria ranged from 12.1% (95% CI, 8.8%–15.4%) to 25.4% (95% CI, 15.2%–35.6%), the prevalence of reduced eGFR ranged from 7.3% (95% CI, 5.5%to9.1%) to 12.5% (95% CI, 7.8%–17.2%), and the prevalence of both albuminuria/reduced eGFR ranged from 2.4% (95% CI, 1.6%–3.2%) to 7.2% (95% CI, 2.7%–11.7%) across Networks.

The Stroke Buckle, Stroke Belt, and Other Regions

Table S5 shows the prevalence of albuminuria, reduced eGFR, and both albuminuria/reduced eGFR for the Stroke Buckle, Stroke Belt, and other regions of the continental US. Data for whites and blacks are provided separately.

DISCUSSION

Using data from a large sample of black and white adults enrolled in an epidemiologic study from across the continental US, we demonstrated substantial geographic variation in the prevalence of albuminuria, reduced eGFR, and both albuminuria/reduced eGFR. A moderate correlation was present between the prevalence of albuminuria and having both albuminuria/reduced eGFR with ESRD incidence rates among whites. ESRD incidence rate correlated only weakly with reduced eGFR in whites; similarly its correlation with albuminuria, reduced eGFR, and both albuminuria/reduced eGFR in blacks was also weak.

Previous studies have reported geographic variation in ESRD incidence rates in both the US and other countries.13–17 Differences in ESRD incidence by US state have been described in multiple studies, dating as far back as 1984.13–15 Furthermore, the 2011 USRDS annual report shows substantial variation in age, race, sex adjusted ESRD incidence rates by Network.18 Potential explanations for these regional differences have been hypothesized. For example, Foxman et al. suggested that analgesic use or occupational exposures to heavy metals, silica, or toxic waste might explain some of the high ESRD incidence rates observed in the US.19 However, there are few data to support these hypotheses.

The geographic variations more recently observed in the prevalence of diabetes20 and hypertension21,22 in the US may contribute to the observed regional differences in ESRD incidence rates. Prior studies have suggested that states with low ESRD incidence rates have fewer cases of diabetic nephropathy.15,23 However, in the current study, only weak to moderate correlations were present between the ESRD Network-specific prevalence of these risk factors and Network-specific ESRD incidence rates. The reason for the low correlation is likely complex, including health system level factors such as disparities in access to primary and specialty care and patient-level factors such as health behaviors and disease severity that may influence CKD progression.

At least one previous study examined whether regional variation in CKD prevalence explains regional variation in ESRD incidence.24 Iseki et al. hypothesized that the well-known variation in ESRD incidence rates observed in Japan were due to variations in CKD prevalence, differential rates of CKD progression, or both. They determined the prevalence of CKD (defined as eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73m2 and, in a separate analysis, eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73m2) among two large community-based screened populations in Ibaraki (n=187,863) and Okinawa (n=83,150), Japan. The key finding was that after multivariable adjustment, CKD was more common in Okinawa than in Ibaraki, particularly for individuals under 60 years of age. For example, the prevalence ratios of eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73m2 among Okinawan men compared to men from Ibaraki age 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, ≥80 years were 2.37, 1.44, 1.10, 1.29, and 1.50, respectively. For women in the same age categories, the prevalence ratios comparing Okinawan women to their counterparts from Ibaraki were 2.10, 2.34, 0.86, 1.11, and 1.26, respectively. Iseki and colleagues concluded that there were, in fact, regional differences in CKD prevalence and that these differences may underlie the variation in ESRD rates in Japan, since ESRD incidence is also higher in Okinawa than in Ibaraki.24,25

In the current study, we observed considerable variation in the prevalence of albuminuria, reduced eGFR, and both albuminuria/reduced eGFR among REGARDS participants, based on their ESRD Network of residence. However, neither albuminuria nor reduced eGFR prevalence was strongly correlated with ESRD incidence rates derived from USRDS data, and the prevalence of both albuminuria/reduced eGFR was moderately correlated with ESRD incidence rates for whites only. One potential explanation for this finding is that blacks with albuminuria and/or reduced eGFR are more likely than whites to die before progressing to ESRD. Several population-based studies of people with CKD have reported higher rates for mortality than for incident ESRD.26–28 For example, over 9.7 years of follow-up of adults with reduced eGFR participating in the Cardiovascular Health Study, the incidence rate for ESRD was 0.5 per 100 person-years, while the all-cause mortality rate was 6.8 per 100 person-years.28

Despite the modest association between albuminuria and reduced eGFR with ESRD incidence observed in the current study, the identification of geographic heterogeneity in CKD prevalence has important implications. CKD is associated with an increased risk for CVD and mortality, and early identification of individuals at risk has the potential to reduce the burden of these outcomes.3,29 Additionally, CKD is associated with increased health expenditures30; therefore, the study findings have implications for resource allocation policy in geographic regions with high CKD prevalence. In addition to identifying these regional variations, understanding why they exist may help eliminate these disparities. Prospective studies of factors contributing to geographic differences in the prevalence of albuminuria and reduced eGFR as well as ESRD incidence are warranted.

The findings of the current study should be considered in the context of certain limitations. First, the analysis assessing the correlation between albuminuria, reduced eGFR, and both albuminuria/reduced eGFR with ESRD incidence rates is ecologic in that we relied on ESRD incidence rates from the USRDS, not the REGARDS study. Therefore, the incident ESRD cases observed are not the same individuals in REGARDS with albuminuria and/or reduced eGFR. While the REGARDS study is assessing ESRD incidence, too few cases have occurred to date to permit the study of geographic variation by ESRD Network. While participation rates for the REGARDS study are similar to those for other large epidemiological studies,31,32 it is possible that participation varied by albuminuria or reduced eGFR status. Thus, although sampling weights were used to account for the stratified enrollment of participants, due to non-participation, we are unable to definitively state that we have a representative sample. An additional limitation is the wide confidence intervals for some of the prevalence estimates. Despite the large sample size in REGARDS, there were a low number of cases of albuminuria, reduced eGFR, and both albuminuria/reduced eGFR in some ESRD Networks. Additionally, albuminuria and reduced eGFR were only assessed at a single time point, and there is a time lag between developing these CKD markers and progressing to ESRD. The current analysis maintains several strengths, most notably the large, population-based sample of blacks and whites. Given the recruitment of adults from across the continental US, we were able to evaluate geographic variation in CKD. An additional strength of the study was the availability of both albuminuria and eGFR.

In conclusion, the current study demonstrates the presence of substantial geographic variation in the prevalence of albuminuria, reduced eGFR, and both albuminuria/reduced eGFR among US adults. We found only modest correlations between albuminuria and reduced eGFR with USRDS-derived estimates of ESRD incidence for US adults. Future investigations into the reasons underlying the geographic variability in ESRD incidence are needed. Explaining these regional differences may provide support for interventions to reduce the burden of ESRD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the REGARDS study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating REGARDS investigators and institutions can be found at www.regardsstudy.org.

Support: This research project is supported by a cooperative agreement U01 NS041588 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Health and Human Services. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NINDS or the NIH. Representatives of the funding agency were involved in the review of the manuscript but not directly involved in the collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data. Additional funding was provided by an investigator-initiated grant-in-aid from Amgen Corporation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no other relevant financial interests.

Note: The supplementary material accompanying this article (doi:_______) is available at www.ajkd.org

References

- 1.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2007 Nov 7;298(17):2038–2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.USRDS. USRDS 2004 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. 2004 doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. The New England journal of medicine. 2004 Sep 23;351(13):1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keith DS, Nichols GA, Gullion CM, Brown JB, Smith DH. Longitudinal follow-up and outcomes among a population with chronic kidney disease in a large managed care organization. Archives of internal medicine. 2004 Mar 22;164(6):659–663. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.6.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. [Accessed August 8, 2011];Renal Data Extraction and Referencing System. http://www.usrds.org/odr/xrender_home.asp.

- 6.Hallan SI, Coresh J, Astor BC, et al. International comparison of the relationship of chronic kidney disease prevalence and ESRD risk. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2006 Aug;17(8):2275–2284. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005121273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, et al. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25(3):135–143. doi: 10.1159/000086678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Annals of internal medicine. 2009 May 5;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forum of ESRD Networks. End Stage Renal Disease Networks: Program Overview. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 10. [Accessed May 7, 2012];The National Forum of ESRD Networks website. About the Forum. http://esrdnetworks.org. [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Census Bureau. [Accessed August 8, 2011];State population estimates by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin for 2005. 2005 http://www.census.gov/popest/datasets.html.

- 12.USRDS. USRDS 2010 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eggers PW, Connerton R, McMullan M. The Medicare experience with end-stage renal disease: trends in incidence, prevalence, and survival. Health care financing review. 1984 Spring;5(3):69–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.USRDS. USRDS 1989 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosansky SJ, Huntsberger TL, Jackson K, Eggers P. Comparative incidence rates of end-stage renal disease treatment by state. American journal of nephrology. 1990;10(3):198–204. doi: 10.1159/000168081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wimmer F, Oberaigner W, Kramar R, Mayer G. Regional variability in the incidence of end-stage renal disease: an epidemiological approach. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2003 Aug;18(8):1562–1567. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Usami T, Koyama K, Takeuchi O, Morozumi K, Kimura G. Regional variations in the incidence of end-stage renal failure in Japan. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2000 Nov 22–29;284(20):2622–2624. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.USRDS. USRDS 2011 annual data report: atlas of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the United States. 2011 doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foxman B, Moulton LH, Wolfe RA, Guire KE, Port FK, Hawthorne VM. Geographic variation in the incidence of treated end-stage renal disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 1991 Dec;2(6):1144–1152. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V261144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voeks JH, McClure LA, Go RC, et al. Regional differences in diabetes as a possible contributor to the geographic disparity in stroke mortality: the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke Study. Stroke a journal of cerebral circulation. 2008 Jun;39(6):1675–1680. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.507053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kershaw KN, Diez Roux AV, Carnethon M, et al. Geographic variation in hypertension prevalence among blacks and whites: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. American journal of hypertension. 2010 Jan;23(1):46–53. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Obisesan TO, Vargas CM, Gillum RF. Geographic variation in stroke risk in the United States. Region, urbanization, and hypertension in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Stroke a journal of cerebral circulation. 2000 Jan;31(1):19–25. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moulton LH, Port FK, Wolfe RA, Foxman B, Guire KE. Patterns of low incidence of treated end-stage renal disease among the elderly. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 1992 Jul;20(1):55–62. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80317-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iseki K, Horio M, Imai E, Matsuo S, Yamagata K. Geographic difference in the prevalence of chronic kidney disease among Japanese screened subjects: Ibaraki versus Okinawa. Clinical and experimental nephrology. 2009 Feb;13(1):44–49. doi: 10.1007/s10157-008-0080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakai S, Wada A, Kitaoka T, et al. An overview of regular dialysis treatment in Japan (as of 31 December 2004) Therapeutic apheresis and dialysis : official peer-reviewed journal of the International Society for Apheresis, the Japanese Society for Apheresis, the Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy. 2006 Dec;10(6):476–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2006.00440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tonelli M, Muntner P, Lloyd A, et al. Using proteinuria and estimated glomerular filtration rate to classify risk in patients with chronic kidney disease: a cohort study. Annals of internal medicine. 2011 Jan 4;154(1):12–21. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-1-201101040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins AJ, Li S, Gilbertson DT, Liu J, Chen SC, Herzog CA. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease in the Medicare population. Kidney international. Supplement. 2003 Nov;87:S24–S31. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.64.s87.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalrymple LS, Katz R, Kestenbaum B, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the risk of end-stage renal disease versus death. Journal of general internal medicine. 2011 Apr;26(4):379–385. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1511-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warnock DG, Muntner P, McCullough PA, et al. Kidney function, albuminuria, and all-cause mortality in the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2010 Nov;56(5):861–871. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith DH, Gullion CM, Nichols G, Keith DS, Brown JB. Cost of medical care for chronic kidney disease and comorbidity among enrollees in a large HMO population. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2004 May;15(5):1300–1306. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000125670.64996.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson R, Chambless LE, Yang K, et al. Differences between respondents and nonrespondents in a multicenter community-based study vary by gender ethnicity. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Investigators. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1996 Dec;49(12):1441–1446. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MESA web. [Accessed May 8, 2012];MESA exam 1 participation rate (10/13/2004) 2004 http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org/participation.aspx.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.